Abstract

Background

Ensuring high quality and equitable maternity services is important to promote positive pregnancy outcomes. Despite a universal health care system, previous research shows neighborhood-level inequities in utilization of prenatal care in Manitoba, Canada. The purpose of this population-based retrospective cohort study was to describe prenatal care utilization among women giving birth in Manitoba, and to determine individual-level factors associated with inadequate prenatal care.

Methods

We studied women giving birth in Manitoba from 2004/05–2008/09 using data from a repository of de-identified administrative databases at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. The proportion of women receiving inadequate prenatal care was calculated using a utilization index. Multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify factors associated with inadequate prenatal care for the population, and for a subset with more detailed risk information.

Results

Overall, 11.5% of women in Manitoba received inadequate, 51.0% intermediate, 33.3% adequate, and 4.1% intensive prenatal care (N = 68,132). Factors associated with inadequate prenatal care in the population-based model (N = 64,166) included northern or rural residence, young maternal age (at current and first birth), lone parent, parity 4 or more, short inter-pregnancy interval, receiving income assistance, and living in a low-income neighborhood. Medical conditions such as multiple birth, hypertensive disorders, antepartum hemorrhage, diabetes, and prenatal psychological distress were associated with lower odds of inadequate prenatal care. In the subset model (N = 55,048), the previous factors remained significant, with additional factors being maternal education less than high school, social isolation, and prenatal smoking, alcohol, and/or illicit drug use.

Conclusion

The rate of inadequate prenatal care in Manitoba ranged from 10.5–12.5%, and increased significantly over the study period. Factors associated with inadequate prenatal care included geographic, demographic, socioeconomic, and pregnancy-related factors. Rates of inadequate prenatal care varied across geographic regions, indicating persistent inequities in use of prenatal care. Inadequate prenatal care was associated with several individual indicators of social disadvantage, such as low income, education less than high school, and social isolation. These findings can inform policy makers and program planners about regions and populations most at-risk for inadequate prenatal care and assist with development of initiatives to reduce inequities in utilization of prenatal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Prenatal care is important to achieving a healthy pregnancy and birth and positively influencing the health of the fetus and child [1]. The Marmot Review [2], “Fair Society, Healthy Lives,” emphasized the importance of ensuring high quality maternity services across the social gradient. Despite the emphasis placed on the value of prenatal care, a portion of the childbearing population continues to receive inadequate prenatal care, defined as receiving no prenatal care, initiating care later than the first trimester, or, given a first trimester start of care, receiving less than the recommended number of visits [3]. In the United States (U.S), 11.2% of women received inadequate prenatal care in 2004 [4], while in 2016, 77.1% of women began prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy, 4.6% began care late (in the third trimester), and 1.6% had no prenatal care, with significant disparities by race/ethnicity [5]. In Canada, national population-level data are not collected on utilization of prenatal care and therefore the rate of inadequate prenatal care is not included as an indicator in the Perinatal Health Reports published by the Public Health Agency of Canada [6, 7]. One older study reported an 8.9% rate of inadequate prenatal care in the Canadian province of Manitoba in 1987/88 [8], while another reported a rate of 6.9% from 1991 to 2000 [9], using different measures of prenatal care utilization. Given that Canada has a universal health care system, and women are not required to pay for prenatal care, these findings suggest inequities in utilization of prenatal care and the existence of barriers other than cost of care. Marmot defines inequity as an inequality or difference that is not fair or just, and is preventable and avoidable [10].

Inadequate prenatal care is a well-recognized risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes [11, 12]. In a study of over 28 million births in the U.S., inadequate prenatal care was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, stillbirth, and early and late neonatal death [11]. In addition, there is growing evidence of an association between prenatal care utilization and subsequent use of postpartum care [13] and well child visits [14, 15]. Thus, efforts to reduce inequities in utilization of prenatal care may contribute to improved maternal and child outcomes. Although several studies on factors associated with inadequate prenatal care have been conducted in the U.S. and other high-income countries [16], the results are not necessarily generalizable to the Canadian population, with its different health care system and racial/ethnic composition. Only a few studies have explored use of prenatal care in the Canadian context [8, 17,18,19,20,21,22].

In previous work, members of our research team conducted a population-based ecologic study of women having singleton live births in Manitoba from 1991 to 2000 to identify neighborhood-level determinants of prenatal care utilization [9]. We found wide regional variations in the proportion of women receiving inadequate prenatal care, with rates ranging from 1.1 to 21.5% across 498 geographic areas. There was a geographic concentration of high rates of inadequate prenatal care in the inner-city of Winnipeg and in northern Manitoba, areas known to be more socio-economically deprived. After adjusting for individual characteristics of age and parity, women living in areas with the highest proportion of the population who were unemployed, Aboriginal, recent immigrants, single parent families, or having less than 9 years of education, or who lived in areas with the lowest average household income, had the highest rates of inadequate prenatal care [9]. This earlier study provided initial evidence of inequities in use of prenatal care. The purpose of the current population-based study was to expand our understanding of individual-level factors associated with inadequate prenatal care in Manitoba.

Since 2000, new initiatives with the potential to improve use of prenatal care have been implemented in Manitoba, such as the Healthy Baby program [23,24,25] and regulation of the profession of midwifery [26], creating a need for an updated study of prenatal care utilization. There have also been a number of improvements and additions to the databases housed in the Population Research Data Repository at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) that allow researchers to significantly improve upon the approach used in the earlier population-based studies of prenatal care [8, 9]. Because physicians used to bill for provision of prenatal care using a global tariff instead of claiming reimbursement for each visit, earlier studies had to rely on hospital abstracts to identify prenatal care visits, which were abstracted from the prenatal record; these data had a high percent of missing information (12–15%), and coding of visits was restricted to one digit, therefore limiting the recorded number of prenatal care visits to a maximum of 8 (with a code of 9 indicating missing data). As of 2001, the medical claims system was revised to have physicians submit claims for reimbursement for the initial prenatal visit and each subsequent visit. Around the same time, space for coding of prenatal care visits in the discharge abstracts was increased to two digits. These changes made determination of the timing and number of prenatal care visits more accurate. In addition, earlier research in Manitoba was limited to only a few individual level variables available in the data files, such as age and parity, necessitating greater reliance on area-level variables derived from the Canadian Census. With the incorporation of data files from Healthy Child Manitoba and Manitoba Families at MCHP, individual level variables such as achievement of high school education, social risk factors (social isolation, single parent status) and health behaviors (smoking, alcohol and drug use) from the Families First screen [27] and receipt of income assistance could be studied.

The current population-based study therefore updates and extends our previous work. The objectives of this study were:

-

1.

To describe rates of inadequate, intermediate, adequate, and intensive prenatal care utilization among women giving birth in the province of Manitoba from 2004/05 to 2008/09 and to examine trends over time;

-

2.

To describe variation in rates of inadequate prenatal care by geographical region; and

-

3.

To determine factors associated with inadequate prenatal care.

Methods

Study design, setting, and inclusion criteria

This was a population-based retrospective cohort study of all women giving birth in hospital in Manitoba over a five-year time period, from 2004/05 to 2008/09. We included women with live births, stillbirths, and singleton or multiple births, in order to provide a population-level examination of prenatal care utilization across the spectrum of types of births. In 2006, Manitoba had a population of 1,148,401 people, and the metro area population for the capital city of Winnipeg was 694,668 people [28]. There were approximately 14,000 to 15,000 births per year in Manitoba during the time frame of this study, and women received prenatal care from obstetricians (41%), family physicians (35%), midwives (4.7%) or a mix of providers (19.1%) in 2008/09 [29]. The provincial Ministry of Health provides comprehensive universal health care coverage for essentially all residents of Manitoba.

Data sources

We analyzed data from existing administrative databases available in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository (hereafter referred to as the Repository) housed at the MCHP in the University of Manitoba. This Repository is an extensive, person-level, linkable but de-identified collection of administrative databases for all permanent residents of Manitoba, covering both health and social services records. The validity and utility of information in the repository has been well documented [30,31,32]. The specific data files analyzed for this project were as follows:

-

Hospital Abstracts file includes information on all hospitalizations of Manitoba residents, including birth hospitalization information and date of initiation of prenatal care and number of visits abstracted from the prenatal care record.

-

Medical Claims/Medical Services file includes information on claims for physician visits, including the service provided, the date of service and a diagnosis code on all ambulatory care contacts for residents of Manitoba, as well as information about physicians’ specialties.

-

Drug Program Information Network file includes information on all prescription medications dispensed in the community to Manitoba residents, including prenatal use of prescription medications.

-

Manitoba Health Insurance Registry includes information on all Manitobans registered for health care in the province (including demographics such as age of mother and place of residence) and can be used to derive marital status, number of children, and residential postal code, and to determine when residents have moved into or out of the province.

-

Canada Census public access file includes area-level sociodemographic information such as average household income, attributed to the population at an aggregate level via the residential six-digit postal code.

-

Families First Screen file from Healthy Child Manitoba includes information on 39 social, biological, and demographic risk factors collected by public health nurses within a week of the newborn’s discharge from hospital.

-

Employment and Income Assistance data file from Manitoba Families includes information on Manitoba residents who receive support from the Income Assistance Program, a provincial program of last resort for people who need help to meet basic personal and family needs.

A detailed description of the databases can be found online [33].

Variables

Outcome variable: Utilization of prenatal care

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) recommends that women receive prenatal care visits every 4 to 6 weeks in early pregnancy, every 2 to 3 weeks after 30 weeks’ gestation, and every 1 to 2 weeks after 36 weeks’ gestation [34], while the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend that women with an uncomplicated first pregnancy be examined every 4 weeks for the first 28 weeks of pregnancy, every 2 to 3 weeks until 36 weeks gestation, and weekly thereafter, while parous women may be seen less frequently [35]. Several indices have been developed to measure the adequacy of prenatal care use, taking into account the month prenatal care began, the number of prenatal visits, and the gestational age at delivery [36, 37]. We selected the Revised Graduated Index of Prenatal Care Utilization (R-GINDEX) [36] for use in this study as it improves on earlier indices and performed well in one of our previous studies [38]. The R-GINDEX is based on the ACOG recommendation for prenatal care visits, and assigns women to one of six categories of care: “no care,” “inadequate,” “intermediate,” “adequate,” “intensive,” and “missing.” For example, at 40 weeks gestation, a woman who began prenatal care in the first 3 months and received between 13 to 16 visits would be categorized as having adequate care, whereas a woman who began care between 1 to 6 months of pregnancy and had less than 8 visits would be categorized as having inadequate care. The intensive care category includes women who have an unexpectedly large number of prenatal care visits, which may indicate potential morbidity or complications.

Information on three birth–related outcomes was used to calculate the R–GINDEX: the gestational age of the infant (obtained from hospital abstracts), the trimester during which prenatal care began, and the total number of prenatal visits during pregnancy. We recorded weeks gestation at the first prenatal care visit and total number of visits from both the hospital abstracts and medical claims files, and used the lower number of weeks gestation and the higher number of visits to reduce the possibility of misclassification of R-GINDEX categories.

Independent variables

We selected several independent variables that might be associated with utilization of prenatal care based on a review of the literature and availability of variables in the Repository. Maternal age group, young maternal age (< 20 years) at first birth, and parity were obtained from the Hospital Abstracts, while information on maternal education less than grade 12 and a composite variable of smoking, alcohol and/or illicit drug use during pregnancy were obtained from the Families First Screen. Table 1 provides a description of the additional independent variables and how they were defined and calculated. We included selected maternal pre-existing medical conditions and complications of pregnancy because a previous study found that women with medical risks during pregnancy made more prenatal visits [39].

Data analysis

Rates of prenatal care utilization were calculated for each of the five fiscal years, in order to describe and compare the proportion of women in the no care, inadequate, intermediate, adequate, and intensive categories of prenatal care over time. Thereafter, we combined no care with inadequate prenatal care into one variable for the remaining analyses. Geographical comparisons of rates of inadequate prenatal care between regions of the province were conducted, and the Manitoba provincial average was used as the reference point to determine statistically high, similar, or low rates. A linear trend analysis determined if there was a statistically significant trend in rates of inadequate prenatal care over time, using the Cochran-Armitage Trend Test. Statistical significance for all analyses was defined as p < 0.05.

Univariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine geographic, socio-demographic and pregnancy-related factors associated with inadequate prenatal care (compared to the reference category of intermediate/adequate prenatal care). Unadjusted odds ratios (uORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the association between each independent variable and the outcome were calculated. Women with intensive prenatal care were excluded from these analyses. We assessed multicollinearity among the independent variables based on variation inflation factors (VIFs) and tolerance levels (TLs), with multicollinearity defined as VIFs > 2.5 and TLs < 0.40 [40]. Variables with significant uORs were entered into multivariable regression models in order to determine adjusted ORs (aORs) and 95% CI. Two multivariable models were generated: one model for all women in the population giving birth from 2004/05 to 2008/09 (after exclusions), and a second model based on a subset of women having the Families First screen, which captures approximately 80% of the population [27]. Because data missing from the Families First screen may not be random, we reported proportions of missing data for these variables and included the missing category in the regression analyses. The c statistic, or area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, was calculated to measure the ability of the models to correctly classify those with and without inadequate prenatal care [41]. The statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Software Version 9.2 (Copyright © SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, U.S.).

Lastly, because some women had more than one delivery during the period of study, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to remove the effect of multiple deliveries (or observations that were not independent). For women with more than one delivery, we randomly selected one delivery per woman and excluded the other deliveries, and then re-ran the multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Results

Participants

There were a total of 70,612 deliveries in Manitoba from 2004/05 to 2008/09. We excluded maternal delivery records that could not be linked to a newborn birth record (0.74%), with a recorded gestation out of range, defined as < 18 or > 45 weeks (0.83%), with a recorded birth weight < 400 g and gestation > 22 weeks (0.06%), and with a maternal Personal Health Identification Number (PHIN) not found on Manitoba Health Registry (0.01%) or not covered by Manitoba Health Registry during pregnancy (2.66%). We excluded midwifery cases having a home birth (0.8%) since prenatal care was not well recorded for those cases. We also excluded midwifery cases of mothers delivered in hospital who were missing a prenatal care record (0.06%), because medical claims data could not be used to determine prenatal care visits as midwives are reimbursed via salary. Lastly, we excluded 211 deliveries that were missing data on the variables required to calculate the R-GINDEX category. These exclusions resulted in a final sample size of 68,132 deliveries, of which 927 of the deliveries were multiple births.

Utilization of prenatal care

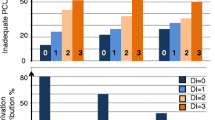

From 2004/05 to 2008/09, the rate of no prenatal care ranged from 0.4 to 0.5%, inadequate care from 9.9 to 12.0%, intermediate care from 50.1 to 51.6%, adequate care from 32.2 to 34.1% and intensive care from 3.6 to 4.3% (Table 2).

Overall, 11.5% of women had either no care or inadequate prenatal care (hereafter referred to as a combined variable of inadequate prenatal care), and there was a significant increase in the rate of inadequate prenatal care from 10.5 to 12.5% over time (Table 3). Three-quarters (74.5%) of women initiated prenatal care in the first trimester, 22.7% in the second trimester, and 2.6% in the 3rd trimester, while overall 0.5% of women did not receive any prenatal care.

Regional variation in prevalence of inadequate prenatal care

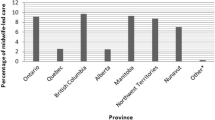

There was significant variation in rates of inadequate prenatal care by geographic district across the province and the city of Winnipeg (Fig. 1). The primarily northern regions of Interlake, North Eastman, Parkland, Nor-Man, and Burntwood all had rates of inadequate prenatal care that were significantly higher than the Manitoba average (Figs. 2 & 3). As well, rates of inadequate prenatal care also varied across the Winnipeg community areas, with the inner-city areas of Inkster, Point Douglas, and Downtown having rates that were significantly higher than the Winnipeg average (Figs. 4 & 5).

Map of Regional Health Authorities in Manitoba in effect from 2004/05 to 2008/09, corresponding to Fig. 2. Reproduced with permission from the report: Heaman M, Kingston D, Helewa ME, Brownell M, Derksen S, Bogdanovic B, McGowan KL, Bailly A. Perinatal Services and Outcomes in Manitoba. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, November 2012

Map of Community Areas in the city of Winnipeg, corresponding to Fig. 4. Reproduced with permission from the report: Heaman M, Kingston D, Helewa ME, Brownell M, Derksen S, Bogdanovic B, McGowan KL, Bailly A. Perinatal Services and Outcomes in Manitoba. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, November 2012

Factors associated with Inadequate prenatal care

The proportions of maternal characteristics among deliveries with inadequate prenatal care, adequate/intermediate prenatal care, and intensive prenatal care are presented in Table 4. We excluded deliveries with intensive prenatal care (n = 2799) from the regression analyses because a high proportion of women with preexisting conditions or pregnancy complications received intensive care, and these deliveries were therefore judged to be inappropriate to include as part of the reference group. None of the variance inflation factors were > 2.5 (most were < 1.5) and none of the tolerance values were < 0.4 for the variables, indicating that multicollinearity was not a problem in the models.

In the first model of all deliveries in the population (N = 64,166), shown in Table 5, women were significantly more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care if they lived in the northern (aOR 2.72) or south rural (aOR 1.15) regions of the province compared to the urban areas (the major cities of Winnipeg and Brandon). Women in younger age groups had higher odds of inadequate prenatal care (12–17 years, aOR 1.96; 18–19 years, aOR 1.60; 20–24 years, aOR 1.32) compared to the reference category of 25–29 years, while those 30–34 years had lower odds of inadequate prenatal care (aOR 0.90). Women who were less than or equal to 19 years at their first birth were also at higher odds of inadequate prenatal care (aOR 1.38) compared to women whose first birth was at age 20 or higher. Women who lived in census dissemination areas with an average household income in the 3 lowest income quintiles had higher odds of inadequate prenatal care, compared to those who lived in an area with the highest income quintile. At an individual level, women receiving income assistance had over twice the odds (aOR 2.15) of receiving inadequate prenatal care than women who were not on income assistance. Women were also more likely to have inadequate prenatal care if they were a single parent (aOR 1.85), had a parity of 4 or higher (aOR 2.29), or a short inter-pregnancy interval of either less than 180 days (aOR 3.11) or 180–365 days (aOR 2.26). A variety of medical conditions contributing to an at-risk pregnancy were associated with lower odds of inadequate prenatal care: multiple birth (aOR 0.40), diabetes (aOR 0.47), hypertension (aOR 0.76), antepartum hemorrhage (aOR 0.71), and maternal depression or anxiety (AOR 0.80). The c statistic for the first model was 0.83, indicating that the model explained 83% of the area under the ROC curve. Therefore the model had good ability to correctly classify those with and without inadequate prenatal care.

In a second model incorporating deliveries which had Families First screening data (N = 55,048), the previous factors associated with inadequate prenatal care remained significant, with additional significant factors consisting of maternal education of less than high school (aOR 1.93), social isolation (aOR 1.21), and the composite variable of smoking, alcohol, and/or illicit drug use during pregnancy (aOR 1.43) (Table 5). The c statistic for this model was 0.81.

Sensitivity analysis

There were 52,144 women and 68,132 deliveries in our original analysis, with 27% of the women having more than one delivery in the five year time frame. After randomly selecting one delivery per woman and re-running the first model (N = 48,925), the results remained similar, with aORs of similar magnitude and significance (results available upon request). The only exception was that the aOR for age group 30–34 years became non-significant in the sensitivity analysis (aOR 0.906, 95% CI 0.818–1.004).

Discussion

The results of this study describe patterns of utilization of prenatal care in the Canadian province of Manitoba, confirm that inequities in use of prenatal care persist, and identify factors associated with inadequate prenatal care that will help inform policy makers and program planners about which populations and regions are most at-risk for inadequate prenatal care. These findings fill an important gap in knowledge related to utilization of prenatal care in Canada, given the lack of surveillance data on prenatal care at a national level in this country.

In terms of utilization, our findings showed that a high proportion of women in Manitoba (11.5%) had inadequate prenatal care, and the rate significantly increased over time from 10.5 to 12.5% during 2004/05 to 2008/09. This rate of 11.5% is higher than that of 6.9% reported in our earlier study [9], which may be a result of using different prenatal care utilization indices – GINDEX [42] versus R-GINDEX [36] - and of improvements in capturing prenatal care utilization in the administrative databases. The higher rates may also reflect changes in provision of health care (e.g., fewer family physicians providing prenatal care) [29] and population trends (e.g., higher proportion of immigrants) [43], although the exact reasons require further exploration. Our population-based rate of 11.5% is much higher than the 4.1% rate of inadequate prenatal care reported by Debessai et al. [17] using data from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey [44]. The lower rate reported by Debessai et al. was based on self-report data from a survey of 6421 women in Canada, which may be prone to recall bias, as women may have overestimated their use of prenatal care, and selection bias, as women most at risk of inadequate prenatal care may not have participated in the survey. Findings from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey do, however, provide some explanation for the high rates of inadequate prenatal care in Manitoba, as Manitoba had the highest proportion of women who reported not getting prenatal care as early as they wanted (18.6%) compared to the other provinces [44].

Studies from the U.S. and Europe found that a lack of health insurance was an important risk factor for inadequate prenatal care [45, 46]. Somewhat surprisingly, given our universal health care system, the Manitoba rate of inadequate prenatal care of 11.5% was similar to the rate of 11.2% reported in the U.S. using data from 2004 [4]. However, caution needs to be used in comparing these rates because we used the R-GINDEX, whereas the U.S. rate was calculated from birth certificate data using the Adequacy of Prenatal care Utilization Index (APNCU) [47], and rates vary depending on which index is used [47]. Although women in a universal health care system do not have to pay for prenatal care visits, other economic, psychosocial, attitudinal and structural barriers have been shown to negatively influence access to care among women in Manitoba, such as stress and family problems, having an unplanned pregnancy, the costs of transportation and child care, not knowing where to get care or having a long wait for care, and fear of apprehension of the infant by the child welfare agency [18]. Similar barriers have been reported in other studies [48,49,50], suggesting that health insurance is only one of many factors influencing use of prenatal care. However, only 0.5% of women in Manitoba had no prenatal care, providing evidence that the majority of women (95.5%) accessed at least some prenatal care. Our rate of 0.5% is lower than the rate of 1.0% of women who had no prenatal care in a hospital register based study in Finland, another country which offers free prenatal care [51]. Our Manitoba rate of no prenatal care was also lower than the U.S. rates of 1.9% in 2008 [52] and 1.6% in 2016 [5].

Our findings showed wide variation in rates of inadequate prenatal care across geographic regions in Manitoba, indicating the persistence of inequities in use of prenatal care similar to the findings of our previous study [9]. The northern regions of the province and inner-city areas in Winnipeg continued to have the highest rates of inadequate prenatal care, and are known to be more socioeconomically deprived. In addition, northern or rural residence was a significant independent factor associated with inadequate prenatal care in the regression models. Possible reasons for this finding might include less access to health care services and prenatal care providers in northern and rural areas of the province, compounded by problems of distance to travel for care. Utilization of prenatal care also followed a clear social gradient, with rates of inadequate prenatal care steadily increasing from a low of 4.8% in the most affluent neighborhoods (income quintile 5) to a high of 21.3% in the poorest neighborhoods (income quintile 1). Living in a neighborhood with the lowest average household income was associated with almost twice the odds (aOR=1.92) of inadequate prenatal care compared to living in a neighborhood with the highest average household income.

Inadequate prenatal care was associated with several individual-level indicators of social disadvantage, such as low income (receiving income assistance), education less than high school, being a single parent, and being assessed as socially isolated. This association between inadequate prenatal care and social disadvantage is similar to findings from other developed countries such as New Zealand [53], England [54, 55] and Belgium [39] and with findings of a systematic review of determinants of prenatal care in high income countries [16]. We also found that young maternal age, high parity, and smoking, alcohol or drug use were factors associated with inadequate prenatal care, congruent with the findings of other studies [11, 16, 39].

To our knowledge, two of our variables have not been studied in previous work and add new knowledge on factors associated with inadequate prenatal care: short inter-pregnancy interval and young maternal age (< 20 years) at first birth. Birth spacing can be measured using inter-pregnancy interval, defined as the time between the last delivery and conception of the current pregnancy [56, 57]. Our results showed that a short inter-pregnancy interval of either less than 180 days, or between 180 and 365 days were both associated with an increased odds of inadequate prenatal care (aOR of 3.11 and 2.26 respectively). Women with closely spaced pregnancies may lack the time or energy to seek prenatal care due to child care responsibilities, or may view prenatal care as unnecessary given the short time since the previous pregnancy. Young maternal age (< 20 years) at first birth was associated with increased odds of inadequate prenatal care (aOR = 1.38). Although young maternal age at first birth is likely at least partly a proxy for lower socioeconomic status, and is associated with number of children in the family, its independent association with inadequate prenatal care in the multivariable regression analyses in this study demonstrates having her first child at a young age may continue to influence a woman’s prenatal care utilization in subsequent pregnancies. In other research, young maternal age at first birth was associated with increased risks of poor health, social and education outcomes among children of prior teen mothers, similar to risks found for children of teen mothers [58].

Our findings also showed that medical conditions such as multiple birth, hypertensive disorders, antepartum hemorrhage, diabetes, and prenatal psychological distress were associated with lower odds of inadequate prenatal care, which suggests that pregnant women with medical risks may seek out more prenatal care, or may have more prenatal care due to increased follow-up and/or referrals to specialists, or more prenatal care may have led to more diagnoses. A higher proportion of women with these conditions received intensive prenatal care compared to those without the condition, as shown in Table 4. Similarly, Beeckman et al. [39] found that women with medical risks during pregnancy made 12% more prenatal visits compared to those without medical risk, while Petrou [59] reported that pregnant women in England and Wales with high risk status at booking had slightly more visits. A study conducted by Krans et al. [60] in Michigan showed that women with high medical risk pregnancies and dual high medical and high psychosocial risk pregnancies were more likely to receive “adequate plus” prenatal care. However, high psychosocial risk pregnancies were more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has several strengths. This study used administrative data to describe utilization of prenatal care and factors associated with inadequate care for the population of women giving birth in Manitoba. Linked administrative databases are a powerful resource for studying important public health issues [30]. However, one important limitation of administrative data is the frequent lack of individual-level socioeconomic information [30]. We were able to overcome that limitation through using highly reliable individual-level information on receipt of income assistance, in addition to ecologic measures such as area-based household income. We were also able to assess social and health behavior factors recorded in the Families First screen.

However, our study also has limitations. This was an observational study, so cause and effect cannot be inferred. In the multivariable regression analyses, multiple individual comparisons could lead to Type 1 error, creating a potential limitation regarding any single factor being studied. In addition, administrative data may be subject to a certain degree of coding errors and incomplete data, which may be random or contain systematic biases. For example, the Families First screening data were available for approximately 80% of the population, and excluded women living in First Nations communities and women having a stillbirth. The completeness of data on number of prenatal visits may be lower for women in some isolated northern communities or other locations where they may be served by salaried physicians, resulting in an over-estimation of rates of inadequate prenatal care.

We selected the R-GINDEX to categorize prenatal care utilization, which is one of several available indices. As previously described, the R-GINDEX is based on the ACOG recommendations for number of visits for low risk pregnant women. Alexander and Kotelchuck note that the effectiveness of this standard has not been assessed through rigorous scientific testing, nor has adequacy of care for women with high risk pregnancies been operationalized [61]. The R-GINDEX is strictly a measure of utilization and only reflects the quantity of prenatal care; it does not measure the content, clinical adequacy, or quality of prenatal care. As well, inaccurate ascertainment of gestational age may affect assignment to a prenatal care utilization category. Our measure of prenatal care also did not take into account use of other maternal health services which may supplement prenatal care, such as participation in the Healthy Baby community support program or prenatal classes.

We were unable to examine maternal characteristics such as unplanned pregnancy, stress and homelessness, which were not captured in the administrative databases. In addition, this study was limited to women having a hospital birth, and excluded the small proportion of women having a home birth with a midwife (0.8%) due to lack of reliable information on number of prenatal visits from the midwifery data. We used firstborn child as the reference category for interpregnancy interval in order to include the full spectrum of birth orders and retain primiparous women in the analysis, based on work by Auger and colleagues [56]. We recognize that some investigators consider the appropriate unexposed category to be women with longer interpregnancy intervals, particularly for studies examining the association between interpregnancy interval and birth outcomes [57]. Lastly, although other studies have found that immigrant women [17, 62] and First Nations women [19, 63] are at higher risk of inadequate prenatal care, the Repository does not include individual-level information on race/ethnicity or immigrant status, so we were unable to study the association of these factors with use of prenatal care. Caution needs to be used in generalizing the results of this study to other Canadian provinces which may have different proportions of First Nations and immigrant women in the population than Manitoba, and different proportions of types of prenatal care providers.

Implications for practice

Marmot contends that universal health coverage is an important step toward improving access to primary health care, but will not by itself reduce health inequities without also taking action on the social determinants of health [64]. The results of this study confirm that several social determinants of health are associated with inadequate use of prenatal care, such as low income, low education, and rural or northern region of residence. Work to improve social determinants of health needs to be done both within the health sector, and through complementary activities outside health care related to housing, income, education and employment [64]. The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada [1] emphasized the need to address the broader social issues affecting pregnant women, such as low income, homelessness, and substance use, and stated, “Programs that work to break down barriers to prenatal care through community outreach have shown some success through targeting distressed communities and individuals” (p. 52).

Public health interventions to improve prenatal care utilization are important because of the potential to reduce unfavorable births outcomes [12]. Studies in the provinces of Manitoba and Newfoundland have shown that participation in prenatal support programs may improve birth outcomes [24, 25, 65]. Handler and Johnson [66] refer to prenatal care as “a critical anchor of the reproductive/perinatal health continuum for women who do become pregnant, often providing a woman’s first encounter with the health care delivery system” (p. 2221) The factors associated with inadequate prenatal care in this study offer some direction for improving use of prenatal care through strategies such as reduction of teenage pregnancy, optimal birth spacing, cessation of smoking and drug abuse, provision of social support, and providing an income supplement during pregnancy such as the Manitoba Prenatal Benefit [25]. Other authors have recommended paying special attention to socially vulnerable women to reduce variations in use of prenatal care [39, 67] or more systematic attention to the roles of social disadvantage [68], and using a multidisciplinary approach [69]. In Manitoba, we have built on the results of our previous work [9, 18, 70, 71] by implementing health system improvements to reduce inequities in access to and use of prenatal care in inner-city Winnipeg [72, 73].

Conclusion

Inequities exist in utilization of prenatal care in the province of Manitoba, with wide variations in rates of inadequate prenatal care across geographic regions. Inadequate prenatal care was associated with several individual indicators of social disadvantage, such as low income, education less than high school, and social isolation. Knowledge of these inequities in utilization of prenatal care will help inform policy makers and program planners about which regions and populations are most at-risk for inadequate prenatal care and assist with development of initiatives to reduce inequities in utilization of prenatal care.

Abbreviations

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ACOG:

-

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odd Ratio

- APNCU:

-

Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- GINDEX:

-

Graduated Index of Prenatal Care Utilization

- HIPC:

-

Health Information Privacy Committee

- MCHP:

-

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy

- PHIN:

-

Personal Health Identification Number

- R-GINDEX:

-

Revised Graduated Index of Prenatal Care Utilization

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SOGC:

-

Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada

- TL:

-

Tolerance Levels

- U.S.:

-

United States

- uOR:

-

Unadjusted Odd Ratio

- VIF:

-

Variation Inflation Factors

References

The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada: The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2009: Growing Up Well - Priorities for a Healthy Future. http://publichealth.gc.ca/CPHOreport. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

The Marmot Review. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. February 2010. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf . Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

D'Ascoli PT, Alexander GR, Petersen J, Kogan MD. Parental factors influencing patterns of prenatal care utilization. J Perinatol. 1997;17:283–7.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S. Births: final data for 2004. NatlVital StatRep. 2006;55:1–101.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1–55.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Perinatal Health Report, 2008 Edition. Ottawa: Author. p. 2008.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Perinatal Health Indicators for Canada 2013: A report of the Canadian perinatal surveillance system. Ottawa, 2013.

Mustard CA, Roos NP. The relationship of prenatal care and pregnancy complications to birthweight in Winnipeg, Canada. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1450–7.

Heaman MI, Green CG, Newburn-Cook CV, Elliott LJ, Helewa ME. Social inequalities in use of prenatal care in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29:806–16.

Marmot M, Friel S, et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity though action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9.

Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Amer J Perinatol. 2012;29:787–93.

Cox RG, Zhang L, Zotti ME, Graham J. Prenatal care utilization in Mississippi: racial disparities and implications for unfavorable birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:931–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0542-6.

Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Shapiro-Mendoza CK. Postpartum care visits – 11 states and new York City, 2004. CDC MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1312–6.

Chi DL, Momany ET, Jones MP, Kuthy RA, Askelson NM, Wehby GL, Damiano PC. An explanatory model of factors related to well baby visits by age three years for medicaid-enrolled infants: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1).

Cogan LW, Josberger RE, Gesten FC, Roohan PJ. Can prenatal care impact future well-child visits? The experience of a low income population in New York state Medicaid managed care. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:92–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0710-8.

Feijen-De Jong EI, Jansen DE, Baarveld F, Van Der Schans CP, Schellevis FG, Reijneveld SA. Determinants of late and/or inadequate use of prenatal healthcare in high-income countries: a systematic review. EurJ Public Health. 2012;22:904–13.

Debessai Y, Costanian C, Roy M, El-Sayed M, Tamim H. Inadequate prenatal care use among Canadian mothers: findings from the maternity experiences survey. J Perinatol. 2016;36:420–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.218 Epub 2016 Jan 21.

Heaman M, Moffatt M, Elliott L, Sword W, Helewa M, Morris H, Gregory P, Tjaden L, Cook C. Barriers, motivators and facilitators related to prenatal care utilization among inner-city women in Winnipeg, Canada: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:227.

Heaman MI, Gupton AL, Moffatt ME. Prevalence and predictors of inadequate prenatal care: a comparison of aboriginal and non-aboriginal women in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:237–46.

Hiebert S. The utilization of antenatal services in remote Manitoba first nations communities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2001;60:64–71.

Sword W. Prenatal care use among women of low income: a matter of "taking care of self". QualHealth Res. 2003;13:319–32.

Tough SC, Newburn-Cook CV, Faber AJ, White DE, Fraser-Lee NJ, Frick C. The relationship between self-reported emotional health, demographics, and perceived satisfaction with prenatal care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2004;17:26–38.

Healthy Child Manitoba. Healthy baby. http://www.gov.mb.ca/healthychild/healthybaby/ Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Brownell MD, Chartier M, Au W, Schultz J. Program for expectant and new mothers: a population-based study of participation. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:691. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-691.

Brownell MD, Chartier M, Nickel NC, Chateau D, Martens PJ, Sarkar J, et al. Unconditional prenatal income supplement and birth outcomes. Pediatrics 2016;137(6). pii: e20152992. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2992.

Thiessen K, Heaman M, Mignone J, Martens P, Robinson K. Trends in midwifery use in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:707–14.

Brownell M, Chartier M, Santos R, Au W, Roos N, Girard D. Evaluation of a newborn screen for predicting out-of-home placement. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:239–49.

Statistics Canada. 2006 Census of Population 2006. http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/index-eng.cfm. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Heaman M, Kingston D, Helewa ME, Brownell M, Derksen S, Bogdanovic B, McGowan KL, Bailly A. Perinatal services and outcomes in Manitoba. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. 2012. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/perinatal_report_WEB.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Jutte DP, Roos LL, Brownell MD. Administrative record linkage as a tool for public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:91–108. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-100700.

Roos LL, Nicol PJ. A research registry: uses, development, and accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00126-7.

Roos LL, Brownell M, Lix L, Roos NP, Walld R, MacWilliam L. From health research to social research: privacy, methods, approaches. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:117–29.

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Manitoba Population Research Data Repository Data List. http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/chs/departmental_units/mchp/resources/repository/datalist.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines: Healthy beginnings: guidelines for care during pregnancy and childbirth. Ottawa: SOGC; 1998.

American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for perinatal care. 7th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: author; 2012.

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:408–18.

Kogan MD, Alexander GR, Jack BW, Allen MC. The association between adequacy of prenatal care utilization and subsequent pediatric care utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;102:25–30.

Heaman M, Newburn-Cook C, Green C, Elliott L, Helewa M. Inadequate prenatal care and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a comparison of indices. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2008;8:15.

Beeckman K, Louckx F, Putman K. Determinants of the number of antenatal visits in a metropolitan regions. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:527.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 2000.

The area under an ROC curve. http://gim.unmc.edu/dxtests/roc3.htm. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Alexander GR, Cornely DA. Prenatal care utilization: its measurement and relationship to pregnancy outcome. Am J Prev Med. 1987;3:243–53.

Manitoba Labour and Immigration. Manitoba immigration facts - 2014 statistical report. 2015. https://www.immigratemanitoba.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/MIF-2014_E_Web_Programmed.pdf. Accessed 23 Oct 2018.

Public Health Agency of Canada. What Mothers Say. Ottawa: The Canadian maternity experiences survey; 2009.

Ayoola AB, et al. Time of pregnancy recognition and prenatal care use: a population-based study in the United States. Birth. 2010;37:37–43.

Delvaux T, Buekens P, Godin I, Boutsen M. Barriers to prenatal care in Europe. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:52–9.

Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner adequacy of prenatal care index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1414–20.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Walsh D, Lavender T. ‘Weighing up and balancing out': a meta-synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high-income countries. BJOG. 2009;116:518–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02067.x.

Phillippi JC. Women's perceptions of access to prenatal care in the United States: a literature review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54:219–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.01.002.

Sword W. A socio-ecological approach to understanding barriers to prenatal care for women of low income. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29:1170–7.

Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Under-attending free antenatal care is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Public Health. 2007;7:268. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-268 PMCID: PMC2048953.

United States (U.S.) Department of Health and Human Services. Expanded Data From the New Birth Certificate, 2008. National vital statistics reports. 2011; 59(7).

Corbett S, Chelimo C, Okesene-Gafa K. Barriers to early initiation of antenatal care in a multi-ethnic sample in South Auckland. New Zealand NZ Med J. 2014;127:53–61.

Raleigh VS, Hussey D, Seccombe I, Hallt K. Ethnic and social inequalities in women's experience of maternity care in England: results of a national survey. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:188–98. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.090460.

Rowe RE, Magee H, Quigley MA, Heron P, Brocklehurst P. Social and ethnic differences in attendance for antenatal care in England. Public Health. 2008;122:1363–72.

Auger N, Daniel M, Platt RW, Luo ZC, Wu Y, Choinière R. The joint influence of marital status, interpregnancy interval, and neighborhood on small for gestational age birth: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-7.

Wendt A, Gibbs CM, Peters S, Hogue C. Impact of increasing inter-pregnancy interval on maternal and infant health. Paed Per Epid. 2012;26(1):239–58.

Jutte DP, Roos NP, Brownell MD, Briggs G, MacWilliam L, Roos LL. The ripples of adolescent motherhood: social, educational and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen mothers. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.008.

Petrou S, Kupek E, Vause S, Maresh M. Clinical, provider and sociodemographic determinants of the number of antenatal visits in England and Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1123–34.

Krans EE, Davis MM, Schwarz EB. Psychosocial risk, prenatal counseling and maternal behavior: findings from PRAMS, 2004-2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:141 e141–7.

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306–16.

Heaman M, Bayrampour H, Kingston D, Blondel B, Gissler M, Roth C, Alexander S, Gagnon A. Migrant women’s utilization of prenatal care: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:816–36.

Di Lallo S. Prenatal care through the eyes of Canadian aboriginal women. Nurs Womens Health. 2014;18:38–46.

Marmot M. Universal health coverage and social determinants of health. Lancet. 2013;382:1227–8.

Canning PM, Frizzell LM, Courage ML. Birth outcomes associated with prenatal participation in a government support programme for mothers with low incomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:225–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01045.x.

Handler A, Johnson K. A call to revisit the prenatal period as a focus for action within the reproductive and perinatal care continuum. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:2217–27.

Sutherland G, Yelland J, Brown S. Social inequalities in the organization of pregnancy care in a universally funded public health care system. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:288–96.

Gavin AR, Nurius P, Logan-Greene P. Mediators of adverse birth outcomes among socially disadvantaged women. J Women's Health. 2012;21:634–42.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetrical outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864.

Heaman MI, Sword W, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Helewa ME, Morris H, Gregory P, Tjaden L, Cook C. Barriers and facilitators related to use of prenatal care by inner-city women: perceptions of health care providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:2.

Heaman M, Sword W, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Helewa M, Morris H, Tjaden L, Gregory P, Cook C. Perceptions of barriers, Facilitators and Motivators related to use of Prenatal Care: A Qualitative Descriptive Study of Inner-City Women in Winnipeg. SAGE Open Med. 2015;3:2050312115621314.

Heaman M, Tjaden L, Chang ZM, Morris M, Helewa M, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Sword W, Kingston D. Quantitative evaluation of the Partners in Inner-City Integrated Prenatal Care Project [abstract]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:488.

Heaman M, Tjaden L, Chang ZM, Morris M, Helewa M, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Sword W, Kingston D. Evaluation of the Partners in Inner-City Integrated Prenatal Care Project: perspectives of women and health care providers [abstract]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:487–8.

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba. Policies on Use and Disclosure. http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/chs/departmental_units/mchp/resources/access_policies.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dr. Patricia Martens, Co-Principal Investigator (deceased), to the planning, implementation and interpretation of the results of this project. We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to our collaborators for their input: Ms. Deborah Maladrewicz, Information Management & Analytics, Manitoba Health, Seniors & Active Living; Dr. Rob Santos, Healthy Child Manitoba Office; Ms. Dawn Ridd, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living; Ms. Kristine Robinson, former Clinical Midwifery Specialist, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority; and Ms. Elisabeth Dolin, former Maternal and Newborn Health Services Consultant, Manitoba Health. Thanks to Ms. Leah Crockett for developing the maps.

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy for use of data contained in the Population Research Data Repository under project HIPC# 2009/2010 - 28. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. Data used in this study are from the Population Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba and were derived from data provided by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, Healthy Child Manitoba, and Manitoba Families.

Funding

This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant: Maternal and Child Health, in partnership with Public Health Agency of Canada – Health Surveillance and Epidemiology Division (Funding reference number MCH - 97591), $100,000, 07/2009–06/2011, for the project, “Predictors and Outcomes of Prenatal Care: Vital Information for Future Service Planning.” The funding body did not have a role in design of the study or collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript. The following authors were recipients of career support funding during the project:

Dr. Heaman: CIHR Chair in Gender & Health.

Dr. Martens: CIHR/Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) Applied Public Health Chair.

Dr. Brownell: MCHP Population-based Child Health Research Award funded by the Government of Manitoba.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in this article were derived from administrative health and social data as a secondary use. The data were provided under specific data sharing agreements only for approved use at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). The original source data are not owned by the researchers or MCHP and as such cannot be provided to a public repository. The original data sources and approval for use has been noted in the acknowledgments of the article. Where necessary, source data specific to this article or project may be reviewed at MCHP with the consent of the original data providers, along with the required privacy and ethical review bodies. Refer to the MCHP policies on use and disclosure for more detail [74].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Patricia J. Martens is deceased. This paper is dedicated to her memory.

- Patricia J. Martens

Contributions

MIH wrote the grant application, directed the implementation of the study protocol, and had overall responsibility for the research. PJM, MDB, MJC, and MEH contributed to conception and design of the study. SAD was the programmer analyst for the study. KRT assisted MIH with preparation of the submission to Health Research Ethics Board and the Health Information Privacy Committee. MIH, PJM, MDB, MJC, MEH, KRT and SAD contributed to interpretation of the results. MIH drafted the manuscript. All authors provided feedback on the draft manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba (File No. HS11522 [H2009:273]) and the Health Information Privacy Committee (HIPC) of the Government of Manitoba (File No. 2009/2010–28). Because this study used data from de-identified administrative databases that did not include names and addresses, consent to participate was not obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Heaman, M.I., Martens, P.J., Brownell, M.D. et al. Inequities in utilization of prenatal care: a population-based study in the Canadian province of Manitoba. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 430 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2061-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2061-1