Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the characteristics of women in Canada who received care from a midwife during their prenatal period.

Methods

The findings of this study were drawn from the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES), which was a cross-sectional survey that assessed the experiences of women who gave birth between November 2005 and May 2006. The main outcome variable for this study was the prenatal care provider (i.e. midwife versus other healthcare providers). Demographic, socioeconomic, as well as health and pregnancy factors were evaluated using bivariate and multivariate models of logistic regression.

Results

A total of 6421 participants were included in this analysis representing a weighted total of 76,508 women. The prevalence of midwife-led prenatal care was 6.1%. The highest prevalence of midwife-led prenatal care was in British Columbia (9.8%), while the lowest prevalence of midwife-led prenatal care was 0.3% representing the cumulative prevalence in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Yukon. Factors showing significant association with midwife-led prenatal care were: Aboriginal status (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.41–3.64), higher education with bachelor and graduate degree attainment having higher ORs when compared to high-school or less (OR = 2.71, 95% CI: 1.71–4.31 and OR = 3.17, 95% CI: 1.81–5.55, respectively), and alcohol use (OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.17–2.26). Age, marital status, immigrant status, work during pregnancy, household income, previous pregnancies, perceived health, maternal Body Mass Index (BMI), and smoking during the last 3 months of pregnancy were not significantly associated with midwife care.

Conclusions

In general, women who were more educated, have aboriginal status, and/or are alcohol drinkers were more likely to receive care from midwives. Since MES is the most recent resource that includes information about national midwifery utilization, future studies can provide more up-to-date information about this important area. Moreover, future research can aim at understanding the reasons that lead women to opt for midwife-led prenatal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

According to the International Confederation of Midwives, the World Health Organization, and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics: “the midwife is recognized as a responsible and accountable professional who works in partnership with women to give the necessary support, care and advice during pregnancy, labour and the post-partum period, to conduct births on the midwife’s own responsibility and to provide care for the newborn and the infant” [1]. Midwives are available in at least 108 countries around the world, spanning the Americas, Europe, Africa and Asia Pacific [2]. While different combinations of midwife-led continuity, medical-led and shared models of care exist in some developed countries (e.g. Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Ireland), medical doctors remain the primary care providers for the majority of childbearing patients in North America [3].

A Cochrane review performed in 2015 showed that patients of midwife-led continuity model of care (where the midwife is the primary care provider from initial booking until the end of the post-natal period) were less likely to experience the following as compared to other models of care (including obstetrician provided care, family doctor provided care, and shared care): epidural/spinal analgesia, forceps/vacuum vaginal birth, preterm births, amniotomy, episiotomy, fetal loss and neonatal death [3]. Patients in the midwife-led continuity model were also more likely to experience spontaneous vaginal birth and longer duration of labour as compared to the other models of care [3]. No significant differences were found between the different models of care in caesarean birth, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, antenatal hospitalization, labour induction, breastfeeding initiation, mean hospital stay and low birth weight [3]. Therefore, the authors concluded that midwife led care shows no harmful effects and presents some important benefits [3]. Moreover, the midwife-led continuity model shows a trend towards cost-effectiveness when compared to the medical-led care [3].

In Canada, midwives are considered autonomous primary health care professionals providing prenatal care, care during labour and birth and postnatal care [4]. Depending on regional availability, midwives are able to deliver their care in any birth setting including hospitals, birth centres, health clinics or the patient’s home [4]. There are currently over 1500 practicing midwives throughout most regions in Canada, the majority of whom are practicing in Ontario. However, according to the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES), only 6.1% of women in Canada received midwife-led prenatal care in 2005/2006 [5]. More recently, the Canadian Association of midwives has reported that in 2015/2016 only 9.8% of Canadian births were performed with the assistance of a midwife [6]. This underutilization of midwifery in Canada has been attributed to various reasons including: low birth rate, national health insurance for physician care and the high number of physicians and nurses practicing in Canada [7].

Current knowledge of the characteristics of women receiving midwife-led prenatal care and birth is very limited, but generally shows regional variability. In the United States, studies have shown that midwives mostly serve less educated, non-White, teenage mothers [8, 9]. On the other hand, a study in the Netherlands, showed that women who are of other European origin or of Asian origin were more likely than Dutch women to initiate care with a midwife [10]. In addition, a study about birthing services in Victoria, Australia showed that women living in a rural area were slightly more likely to attend midwife clinics than metropolitan hospitals (5.3 and 2.8%, respectively) [11].

In Canada, two studies have reported characteristics of women receiving midwife-led prenatal care [12, 13]. A study performed in Manitoba assessed the trends of midwifery use in the province and found that multiparous women who are between the ages of 20–34 years were more likely to receive midwife-led prenatal care [12]. The second study was performed by Klein et al. on a more national scale with an objective to investigate the attitudes on nulliparous women to birth technology [13]. However, the sample in that study was not representative of the Canadian population due to the sampling method used [13]. Nevertheless, the authors reported that women receiving midwife-led prenatal care were slightly older [13]. Therefore, no representative national-scale studies were found, which describe the characteristics of women receiving midwife-led prenatal in Canada. The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the characteristics of these patients compared with those who receive their care from other models on a Canada-wide scale.

Methods

The present study is a secondary data analysis of the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES), which was performed by Statistics Canada between November 2005 and May 2006. This survey was conducted following the Canadian Census of population, and the sample was selected using information collected in the census. Access to MES data was granted by the Research Data Center (RDC) at York University. The survey was cross-sectional and targeted women who gave birth between February 15 and May 15, 2006 in all Canadian provinces, or between November 1, 2005 and February 1, 2006 in the territories [14]. Moreover, the women had to have had a single birth, were at least 15 years of age at the time of birth and whose babies were born in Canada and lived with the mother no less than one night per month [14]. Women who lived in collective dwellings or on First Nations reserves were excluded [14]. The final sample included 8542 respondents, 6421 of which granted Statistics Canada permission to share their responses [14]. Data collection was done through a Computer Assisted Telephone Interview on the provincial level [14]. If a telephone interview was not possible in the territories, personal interviews were performed with a paper copy of the questionnaire [14]. The average time for the interview was 45 min [14]. Responding to the survey was voluntary, with a response rate of 78% [14]. Details about the design and methodology of MES have been described previously [15]. The protocol of MES has been reviewed by the Health Canada’s Science Advisory Board and Research Ethics Board and the Federal Privacy Commissioner, and approved by the Statistics Canada’s Policy Committee. Since this project was based on secondary data analysis of MES, institutional ethics approval was not required.

For the present study, the main outcome was defined as midwife-led prenatal care asked by the question “From which type of healthcare provider, such as an obstetrician, family doctor or midwife, did you receive most of [your prenatal] care?”. Possible responses to this question were: Obstetrician, Gynecologist, OBGYN, family doctor, General Practitioner (GP), doctor, midwife, nurse or nurse practitioner or other. For the purposes of this study, the outcome variable was dichotomized and the two levels were ‘midwife-led prenatal care’ and ‘other’.

The following variables were evaluated at each level of the outcome variable: Maternal age (three levels: <20, 20–34 and 35+ years of age), aboriginal status, mother’s highest level of education (four levels: high-school or less, post-secondary below bachelor, bachelor degree and graduate degree), mother’s employment status during pregnancy, total annual household income (four levels: <30,000, 30,000–<60,000, 60,000–<100,000 and 100,000 or more Canadian Dollars), marital status (two levels: with partner, without partner), immigration status (two levels: has/had immigrant status and never had immigrant status), self-reported alcohol use during pregnancy, smoking during the last 3 months of pregnancy, perceived health of the mother (three levels: excellent/very good, good and fair/poor), Body Mass Index (BMI) recoded according to Health Canada guidelines [16] (four levels: underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese) and whether this was the mother’s first pregnancy.

Bivariate logistic regressions were used to assess the relationship between the outcome ‘midwife-led prenatal care’ and the covariates. Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CIs) were obtained to assess the relationship between each of the covariates and the outcome variable. A multivariate logistic regression model was also created with the same outcome ‘midwife-led prenatal care’ and the independent variables being all the covariates mentioned above. This resulted in adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for the outcome variable at each covariate. Survey weights were applied to each variable and calculated estimate, making the data more representative of the Canadian population as a whole. Bootstrapping was performed to account for the complex design of the survey. All the analyses were computed in the Stata Statistical Software version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

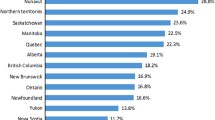

The total number of participants included in this analysis was 6421 participants representing a weighted total of 76,508 women. By province, women residing in British Columbia were more likely to receive midwife-led care at 9.8%, followed by Manitoba (9.4%) and Ontario (9.2%) (Fig. 1). The lowest prevalence of midwife-led care was 0.3% which represented the total prevalence in all of: Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Yukon (Fig. 1).

Frequency of midwife-led prenatal care across different provinces In Canada. * ‘Other’ includes: Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Yukon. These provinces were grouped together due to low cell counts. Data source: Maternity Experiences Survey (MES)

The results of the bivariate and multivariate analyses are shown in Table 1. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the significant factors associated with receiving care from a midwife were: Aboriginal status (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.41–3.65), bachelor and graduate degree attainment when compared to high-school or less (OR = 2.71, 95% CI: 1.71–4.31 and OR = 3.17, 95% CI: 1.81–5.55, for bachelor and graduate level, respectively), and self-reported alcohol use (OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.17–2.26) (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with midwife-led care were age, marital status, perceived health, maternal BMI before pregnancy, whether this was the first pregnancy for that mother, ever having had an immigrant status, and working during pregnancy (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the characteristics of women receiving prenatal care from midwives on a national scale in Canada. Our results show that receiving midwife-led care during pregnancy was influenced most notably by higher levels of education, aboriginal status, and self-reported alcohol use during pregnancy. Moreover, the prevalence of midwife-led prenatal care varies greatly by province, being highest in British Columbia at 9.8% and lowest in all of: Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Yukon (combined prevalence: 0.32%). This study is one of the first to describe the fundamental characteristics of women in Canada who receive prenatal care from a midwife and highlights the importance of gaining more up-to-date statistics of midwifery utilization.

Based on the findings of the present study, the three provinces with the highest uptake of midwife-led prenatal care were British Columbia (9.8%), followed by Manitoba (9.4%) and Ontario (9.2%). However, in general there has been an increase in the uptake of midwife-led prenatal care; nationally increasing from 6.1% in 2005/2006 [5] to 9.8% in 2015/2016 [6]. As of 2016 the three provinces with the highest uptake of midwife-led prenatal care was as follows: British Columbia (21%), Nunavut (15.4%) and Ontario (15.2%), while Manitoba’s uptake has now dropped to 6.5% [6]. Midwifery in Manitoba has been regulated and publicly funded since the year 2000 [17], however, there have been some setbacks in recent years where the newly elected provincial government opted to cancel the existing joint educational program [6]. This could have contributed to the decline in midwife-led prenatal care in Manitoba from 2005/2006 to 2015/2016. On the other hand, the rise in midwife-led prenatal care in Nunavut during that period can be explained by the later regulation of midwifery as a profession in that region, having only been regulated since 2011 [6]. In addition to Nunavut, the following provinces have become regulated since the MES data collection, potentially contributing to the observed increase in the national uptake of midwife-led prenatal care: Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick [6]. Midwifery in Prince Edward Island and Yukon Territory currently lacks a regulating body [6]. Moreover, it seems that with regulation comes funding, and midwifery is now covered by provincial/territorial health care plans in most regions of Canada, potentially increasing accessibility to this service [18]. On the other hand, midwifery is not covered by the health care plan in Prince Edward Island [19]. Unfortunately, no information about midwifery coverage was found for New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Yukon territory.

In terms of demographic characteristics, having aboriginal status was associated with increased likelihood of choosing a midwife. Aboriginal individuals are less likely to seek medical attention through government-run health care systems in Canada, due to factors such as social inequality, decreased specialist referrals, lowered access to higher-tier medical therapies, and decreased standards of medical care (both perceived and actual) [20]. Aboriginal communities are also more likely to look for alternative therapies, perhaps as a result of disintegration throughout the non-aboriginal Canadian community, or as a complement to the increased importance placed on spiritual practices; however, data on the use of this population is under-represented [21].

In terms of socioeconomic factors, higher levels of education, was associated with increased use of midwives. Looking solely at education, previous literature has shown that university-educated women are more likely to feel in charge of their own health, perhaps due to increased education leading to a more keen interest in their own health status [22, 23]. Midwifery programs focusing solely on a more highly-educated demographic may choose to incorporate health literacy as a core component, which may serve to keep their patient demographic involved in their own care and emotionally engaged about the process throughout [24].

In terms of health factors, this study found that alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with higher odds of receiving prenatal care from a midwife. For the purposes of this study, this variable was dichotomoized which may mask the effects of heavy drinking versus light drinking during pregnancy. If this association does exist, however, it may be because alcohol users prefer to avoid using physicians and the national healthcare system for fear of being judged by the physicians, nurses and staff. Alternatively, women receiving care from a midwife may feel more comfortable disclosing their habits (alcohol or otherwise) to one individual. Moreover, alcohol users may not be able to uphold a doctor-patient relationship and may prefer the flexibility of a midwife. Future studies can further investigate the association between alcohol use during pregnancy and receiving prenatal care from a midwife.

The main limitation of this study is that the data used is 10 years old. However, up to the authors’ knowledge, the MES is the most recent database that provides information about the characteristics of midwife-led prenatal care on a national scale in Canada. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design of the survey, which may introduce reverse causality. In addition, with self-reported data, the possibility of information bias should be considered, especially for alcohol use and smoking during pregnancy where respondents may not feel encouraged to provide accurate answers that may present themselves unfavourably. Other contributors to information bias include lack of recall and closed-ended questions, which have a lower validity rate than other question types and the answer options could lead to unclear data due to differences in interpretation by different respondents (for example, the answer option “somewhat agree” may elicit different responses). Last but not least, this study did not control for all of the confounding variables that could have contributed to the associations we found. These include midwife-led care in previous pregnancies and ethnicity. Regardless of these limitations, this study used a large dataset which studied a large amount of predictors and was weighted to represent the Canadian population of pregnant women. This survey also had a high response rate of 78%. As far as the authors are aware, this is the first study that aims to describe the characteristics of women choosing midwife-led prenatal care in Canada on a national scale.

Conclusions

In conclusion, receiving prenatal care from a midwife in Canada is associated with increased education, having an aboriginal status, and consuming alcohol during pregnancy. The prevalence of midwife-led prenatal care also varies greatly by province. Up to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the characteristics of women receiving midwife-led prenatal care in Canada. Further research can provide in-depth understanding of factors that play a role in the increased utilization of midwives during pregnancy and can provide useful clinical practice guidelines to ensure high-quality patient-oriented care, tailored to individual patient preferences and specific circumstances. In addition, future studies and national efforts can provide more up to date information about the characteristics of women receiving midwife-led prenatal care in Canada, especially since midwife-led prenatal care seems to be on the rise in Canada with fluctuating trends in some provinces.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI:

-

95% Confidence Interval

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- MES:

-

Maternity Experiences Survey

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- RDC:

-

Research Data Centre

References

Borrelli SE. What is a good midwife? Insights from the literature. Midwifery. 2014;30:3–10. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613813002015. cited 17 Nov 2015.

ICM. International Confederation of Midwives–Map of activities [Internet]. Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.org/our-members/associations-world-map.html. cited 17 Nov 2015.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD004667. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23963739. cited 4 Nov 2015.

CAM. HOME–Canadian Association of Midwives [Internet]. Available from: http://canadianmidwives.org/. cited 12 Apr 2017.

O’Brien B, Chalmers B, Fell D, Heaman M, Darling EK, Herbert P. The experience of pregnancy and birth with midwives: results from the Canadian maternity experiences survey. Birth. 2011;38:207–15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21884229. cited 3 Dec 2015.

CAM. Midwifery across Canada–Canadian Association of Midwives [Internet]. Available from: http://canadianmidwives.org/midwifery-across-canada/#1467634074483-f50b550d-db87. cited 12 Apr 2017.

Rushing B. Ideology in the Reemergence of North American Midwifery. Work Occup. 1993;20:46–67. Available from: http://resolver.scholarsportal.info/resolve/07308884/v20i0001/46_iitronam.xml. cited 2 Dec 2015.

Stewart SD. Economic and personal factors affecting women’s use of nurse-midwives in Michigan. Fam Plan Perspect. 1998;30:231–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9782046. cited 8 Nov 2015.

Paine LL, Johnson TR, Lang JM, Gagnon D, Declercq ER, DeJoseph J, et al. A comparison of visits and practices of nurse-midwives and obstetrician-gynecologists in ambulatory care settings. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2000;45:37–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10772733. cited 8 Nov 2015.

Anthony S, Amelink-Verburg MP, Korfker DG, van Huis AM, van der Pal-de Bruin KM. [Ethnic differences in preference for home delivery and in pregnancy care received by pregnant women]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152:2514–2518. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19055259. cited 8 Nov 2015.

Brown S, Darcy M-A, Bruinsma F. Having a baby in Victoria 1989–2000: continuity and change in the decade following the Victorian Ministerial Review of Birthing Services. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:242–50. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12141620. cited 8 Nov 2015.

Thiessen K, Heaman M, Mignone J, Martens P, Robinson K. Trends in Midwifery Use in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:707–14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26474227. cited 2 Dec 2015.

Klein MC, Kaczorowski J, Hearps SJC, Tomkinson J, Baradaran N, Hall WA, et al. Birth technology and maternal roles in birth: knowledge and attitudes of canadian women approaching childbirth for the first time. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33:598–608. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21846449. cited 8 Nov 2015.

Statistics Canada. Maternity Experiences Survey (MES) [Internet]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5019. cited 9 Jun 2016.

Dzakpasu S, Kaczorowski J, Chalmers B, Heaman M, Duggan J, Neusy E, et al. The Canadian maternity experiences survey: design and methods. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:207–16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18364098. cited 3 Oct 2016.

Government of Canada, Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch O of NP and P. Body Mass Index (BMI) Nomogram–Food and Nutrition–Health Canada [Internet]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/weights-poids/guide-ld-adult/bmi_chart_java-graph_imc_java-eng.php. cited 24 Apr 2016.

Manitoba Health. Midwifery in Manitoba [Internet]. Available from: http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/primarycare/public/access/maternal/midwifery.html. cited 16 Apr 2017.

NACM. Midwifery Regulatory Frameworks and References to Aboriginal Midwifery [Internet]. Available from: http://www.nacmtoolkit.ca/indigenous-knowledge-and-governance-of-maternal-health/midwifery-regulatory-frameworks-including-references-to-aboriginal-midwifery/. cited 18 Apr 2017.

PEI Association for Newcomers to Canada. Having a Baby [Internet]. Available from: http://www.peianc.com/content/lang/en/page/guide_health_baby. cited 18 Apr 2017.

Browne AJ, Varcoe C. Critical cultural perspectives and health care involving Aboriginal peoples. Contemp Nurse. 2014;22:155–68. Routledge

Young TK. Review of research on aboriginal populations in Canada: relevance to their health needs. BMJ. 2003;327:419–22.

Larsson M. A descriptive study of the use of the Internet by women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery. 2009;25:14–20.

Wiles J, Rosenberg MW. Gentle caring experience. Health Place. 2001;7:209–24.

Renkert S, Nutbeam D. Opportunities to improve maternal health literacy through antenatal education: an exploratory study. Health Promot Int. 2001;16:381–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11733456. cited 14 Jun 2016.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff working at the Research Data Centre (RDC) at York University and for the individuals responsible for the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES). Although the research and analysis are based on data from Statistics Canada, the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Canada but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Authors’ contributions

PA contributed to hypothesis conception, data analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript write-up. SG and NS contributed to manuscript write-up and revisions of the manuscript. AM contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. HT supervised hypothesis conception, data analysis and interpretation and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participation in MES was voluntary. The protocol of MES has been reviewed by the Health Canada’s Science Advisory Board and Research Ethics Board and the Federal Privacy Commissioner, and approved by the Statistics Canada’s Policy Committee. Since this project was based on secondary data analysis of MES, institutional ethics approval was not required.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdullah, P., Gallant, S., Saghi, N. et al. Characteristics of patients receiving midwife-led prenatal care in Canada: results from the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 164 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1350-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1350-4