Abstract

Background

A 32-base pair deletion (∆32) in the open reading frame (ORF) of C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) seems to be a protective variant against immune system diseases, especially human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). We aimed to assess the frequency of CCR5∆32 in the healthy Iranian population.

Methods

In this study, 400 normal samples from Khorasan, northeastern Iran, were randomly selected. The frequency of CCR5∆32 carriers was investigated using PCR analysis. Allele prevalence and the fit to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were analyzed.

Results

The prevalence of CCR5∆32 in the northeastern population of Iran was 0.016. Four hundred samples were studied, among which one with CCR5∆32/∆32 and 11 with CCR5Wild/∆32 genotype were detected.

Conclusion

This study was the first investigation for an assessment of the prevalence of CCR5∆32 in northeastern Iran. The low prevalence of CCR5∆32 allele in the Iranian population may result in the increased susceptibility to HIV-1. In addition, this prevalence is the same as that of reported in East Asia, while is lower than that in the Europeans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Genetic mutations play an important role in the susceptibility and the progression of various human diseases in populations [1]. Chemokines are low-molecular-weight cytokines, which bring leukocytes to the sites of inflammation, infection, or injury. The interaction of chemokines with their receptors can locally control the progression, recruitment, and induction of lymphocytes. Therefore, the chemokine receptors are utmost important in the immune response against pathogens and inflammatory responses [2]. C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) is a seven passed transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor of which variations could elucidate the reason for high susceptibility or the resistance of individuals to a specific infectious disease [2, 3]. The CCR5 is a co-receptor involved in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry into the target cells in the initial phases of infection. The HIV type 1 (HIV-1) attaches to CCR5 on monocytes and macrophages through the infection process [2].

The genetic variations of chemokine and chemokine receptor genes are paramount in their structures and functions. A 32-nucleotide deletion in the exon of CCR5 gene (CCR5∆32) has a considerable influence on the attachment capability of HIV-1 to CCR5, leading to a defective phenotype of the receptor [3]. The CCR5∆32 causes a frame shift and premature stop codon which results in dysfunction of CCR5 [4]. Meanwhile, the CCR5∆32 gene produces a truncated CCR5, which cannot be transported to the cell membrane [5] (Fig. 1). The absence of CCR5 on the cell surface prevents the cellular entry of CCR5-tropic (R5-tropic) HIV-1 strains into the cells [6]. The individuals with homozygote genotype for CCR5Δ32 (CCR5∆32/∆32) are protected against repeated exposure to HIV-1 infection. The CCR5∆32/∆32 causes resistance to HIV infection, while the CCR5Δ32 heterozygote genotype (CCR5Wild/∆32) considerably hinders the onset of AIDS but is not quite protected against it [7]. The CCR5Wild/∆32 genotype is significantly associated with slower HIV-1 disease progression and better response to treatment compared to the wild-type genotype [8]. The CCR5Wild/∆32 T-cells express lower CCR5 than normal T-cells, resulting in lower HIV infection [9, 10]. In addition, a study showed that the CCR5Wild/∆32 genotype caused 2–4 years slower development of AIDS following HIV-1 infection compared to the CCR5Wild/Wild genotype [5]. Moreover, it is also shown that the HIV-1 viral load was 6- to 8-fold lower in CCR5Wild/∆32 compared to CCR5Wild/Wild [5, 11]. Therefore, the CCR5 is an excellent target to develop novel therapeutics for HIV treatment. As there are different frequencies of CCR5∆32 worldwide, we aim to assess the prevalence of the CCR5Δ32 in northeastern Iran (Khorasan Province) for the first time and specify the origin of these genotypes in Iran compared to other countries.

Scheme 1 shows the role of CCR5Δ32 in protection against HIV-1 infection; (a) The normal cell with wild type CCR5 gene: 1. transcription, 2. mRNA transfer to the cytosol, 3. translation, 4. conformation and transferring to the cell membrane, 5. HIV-1 attachment and entry, 6. production of HIV-1 RNA, 7. transferring HIV-1 RNA to the nucleus; (b) A cell with CCR5Δ32 gene: 1. transcription, 2. mRNA transfer to cytosol, 3. translation, 4. wrong conformation and degradation, 5. the absence of CCR5 on the cell surface and naught HIV-1 entry through CCR5

Methods

Study population

In this line, we received 400 blood samples of HIV-negative healthy subjects of the Mashhad cohort study (Grant number: 85134; Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Khorasan northeastern Iran) [12]. The MASHAD cohort study has begun in 2010 in the north-eastern Iran. Individuals were collected from three regions. In this line, each region was separated into nine sites centered [12]. There were 27 clusters in the Mashhad cohort study, which 15 samples of each cluster were randomly selected by the technique of stratified cluster random sampling. In this regard, these samples were almost age- and sex-matched that were included in this study [12]. It is worth mention that we selected healthy individuals without HIV infection or cardiovascular events. Thus, cardiovascular events are not a limitation of our study. For the purpose of this study, the following key data were also extracted from Mashhad cohort study [12]. The extraction of DNA from blood samples was done using Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Genet Bio Company; Korea).

Genotyping

The samples were genotyped by amplification of the region containing CCR5Δ32 using PCR assay. PCR genotyping was experimented as described previously [9]. The forward and reverse primers were as follows, respectively: (5′-AGGTCTTCATTACACCTGCAGC-3′), and (5′-CTTCTCATTTCGACACCGAAGC-3′). It is noteworthy that genotypes were detected according to the final size of PCR products, of which 169 bp and 137 bp products were related to the wild type and the CCR5∆32 genotypes, respectively. Each PCR reaction was experimented in 25 μl containing 5–10 ng of the purified DNA sample (1500 μmol), 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (CinnaGen Company; Iran), 2.5 μl PCR Buffer (10X) (300 μmol), 10 pmol/μl of the reverse primer, and 10 pmol/μl of the forward primer for detecting the CCR5∆32. The PCR reaction was used the Applied Biosystems PCR (Life Technologies Company; United States), under the following thermal conditions: initial denaturation for 3 min at 95 °C; 35–40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and finally elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. In the following, PCR products (7 μl) were electrophoresed on a 2.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen Company; United States) stained with DNA Green Viewer (Pars Tous Company; Iran) using an electrophoresis analyzer (Consort BVBA Company; Germany) and SYNGENE U; GENIUS gel documentation system.

Statistical analysis

The genotyping data were analysed via the SPSS 20.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The genotype and the allele frequencies of CCR5D32 variant were calculated using gene count and the χ2 test. Moreover, Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) assumption was investigated by the Pearson χ2 distribution. In this study, P-values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The demographics of study subjects are summerized in Table 1. The 169-bp band represented the wild-type alleles and the 137-bp band represented the mutant genotype (Fig. 2). Totally, 12 mutant alleles (11 heterozygotes and one homozygote) were detected among all the samples (Table 2). The prevalence of CCR5∆32 allele was 0.016. Although, in this study, all the samples were randomly selected based on the statically selection, data analysis was indicated that allele and genotype distribution of our samples were not in the HWE (P-value = 0.020).

Discussion

Chemokine receptor CCR5 plays a critical role in the entrance of HIV to the host cells and accordingly in the progression of AIDS. Hence, CCR5 is considered as a potential target for both prevention and treatment of HIV infection. Discovery of CCR5∆32 has opened a new field in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. In this case, the investigation of allele distribution in various populations is informative [13]. The CCR5 variations could explain why some people are more susceptible to AIDS than others [11, 14]. Few studies have focused on the genetic susceptibility of Iranian population to HIV-1. The frequency of CCR5∆32 allele in the normal population of North East of Iran has not been investigated. Hence, in the present study, we describe the prevalence of CCR5∆32 among the Iranian population. Moreover, we observed a HWE deviation in this population. It could be due to some reasons, including: CCR5∆32 has a low allelic frequency, and a mixture genetic in this population.

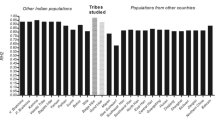

The discuss origin of CCR5∆32 allele is still controversial. The CCR5∆32 allele is mostly considered in the Europeans population [15]. However, this allele has been observed in East and South-East Asian, African, and Indo-American populations [15]. Caucasians are widely distributed in Eurasia, the Middle East, and North Africa [16]. Moreover, the frequency of CCR5∆32 within the Caucasians is different [15]. Furthermore, the CCR5∆32 allele is rarely indicated in the population of North Africa and the Middle East Arabs. The allele distribution in the Europeans has been shown to be distributed in a north-south downhill manner. Several reasons have been noted for distribution of the allele in the Europeans such as population migration, genetic admixture and outbreaks of infectious diseases [17].

Phylogenetic studies have demonstrated that the Iranians are similar to population of northern India, the Greeks and some European populations such as Italian, English, German, Finn and Lapp [16]. However, the CCR5∆32 allele frequency in Iranian population is observed less than the Europeans [18]. Historical and phylogenetic evidence have suggested that Iranian and European populations are divided from a common ancestral population being called Indo-European [19].

According to several studies, the Vikings played a major role in the distribution of the CCR5∆32 allele in Europe. The CCR5∆32 allele is graphically distributed in Europe, Eurasia, and Anatolia in coincidence with the area which the Vikings were dominant [20, 21]. It seems that Vikings are involved in introducing this mutated allele and its related disease to the countries and changed its incidence in the target populations [20, 21]. There is also a strong positive association between CCR5∆32 allele prevalence and the geographic and climatic factors [15]. Historical data suggests that the more combination of Eastern population of Iran with the Mongol invaders and other Eastern nations could have diluted the CCR5∆32 allele prevalence. The high prevalence of the CCR5∆32 allele in the northern and the north-western population of Iran can be contributed to the age of the Vikings or can be due to the less combination with attackers whose allele prevalence was less than that population. The prevalence of CCR5∆32 allele is decreased from North to South of Iran, similarly, the allele prevalence both in North East (according to the results of this study) and in South East of Iran was very low [22,23,24] (Table 3). This is while the prevalence of this allele was higher in the North and North West of Iran [24, 25]. In 2005, Gharagozloo et al. reported the prevalence rate of CCR5∆32 to be 0.0146 among normal individuals in the South of Iran [26]. In 2014, Rahimi et al. reported that CCR5∆32 allelic prevalence was 1.1 and 0.19% for heterozygous and homozygous respectively genotypes in populations of several provinces of Iran [18].

In this case, the allele frequency in the north of Iran (Golestan Province) with different ethnicity and population is higher than another place in Iran. In this line, Shahbazi et al. and Abdolmohammadi et al. identified that allele frequency of CCR5∆32 were 0.09 and 0.072, respectively in north of Iran [24, 29]. Since Golestan Province is already located in the southeast of Caspian Sea, it is supposed to display an higher rate of this polymorphism but due to the presence of different ethnicities living (like Turkmen), the mutant genotype is more prevalent [27]. The different result between Iranian studies may due to genetic diversity among Iranian population [30, 31]. Investigation of genetic systems has been indicated a heterogeneity among Iranian population. Mehrjoo et al., in a genome-wide association study, indicated that there is a distinct genetic diversity and also heterogeneity of the population of Iranian [32]. Comparison of gene distributions with the small number of samples of Iranian population confirmed an intra-ethnic and wide overall genetic mixture in the Iranian population. The genetic diversity reflects the differences in the structure of Iranian populations [30]. Generally, Iran is an ethnically diverse population, comprising of different groups including Pars, Lur,, Kurd, Baloch, Arab, Turkmen, and Turk [30]. Moreover, the complete mtDNA sequence analysis exposed a high genetic diversity in the Iranian population [31].

Historians believe that the most Iranians are Aryan; however they have been mixed with different foreigners during the history, for example Macedonians, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols. Moreover, Iran has a key role in linking different populations in the Silk Road, between Asia and Europe [33]. Ongadi et al. in a systematic review analysis revealed that the CCR5Δ32 allele frequency is at 93% in Caucasians and 7% is in the other populations [34]. The frequencies of this allele in some European countries were demonstrated that is moderate such as Italy (3%), Cyprus (2.8%) and Greece (2.4%), but a high frequency (9.21%) was reported in southwest Germany [35, 36]. Moreover, this frequency is about 4% in Brazilian populations [37]. It is indicated that the distribution of CCR5-∆32 is very low in the south of Middle East and also Arabic countries. According to our study, we observed a low frequency of mutant allele in Iran that it is in almost agreement with the result observed from countries such as Saudi Arabia, and India (1%) [38, 39]. The frequency of CCR5-∆32 allele was indicated in Turkey (3.17%), Afghanistan (3.86%), Pakistan (2.86%) [40, 41].

On the other hand, approximately 0.8% of adults are living with HIV based on the latest data from the WHO [42]. In regions and countries, the burden of the epidemic is different [42]. The prevalence of adults living with HIV is 7.0, 1.5, 0.2, 0.2, 0.4, 0.9, 1.2 and < 0.1% in Eastern and Southern Africa, Western and Central Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Western and Central Europe and North America, Latin America, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, The Caribbean, and Middle East and North Africa [42]. Moreover, the prevalence of HIV among the general population in Iran remains low [42]. In Iran, the main populations at risk of HIV infection are people who inject drugs, prisoners and sex workers [43]. The general population category consisted mainly of research on blood donors in Iran [44]. In Bagheri’s systematic review, the prevalence of HIV in the general population was 0.00% [44]. Importantly, in a study by Haghdoost et al. is indicated that a change in the prevalence of HIV infection from people who inject drugs to the general population. This shift may due to the enhancing rate of premarital and also extramarital sexual contact, particularly with female sex workers in Iran [45]. It also demonstrated that HIV/AIDS burden was not distributed equally among different Iranian provinces, and in some provinces such as Kermanshah, Hormozgan, Lorestan, and Tehran it was more concentrated [46]. Remarkably, no case with HIV infection was detected in the general population of Mashhad [47]. Likewise, the prevalence of infection with HIV in the Iranian population of thalassemia and hemophilia and blood donors was low [48].

Beside genetic modifications, other critical immune factors that may prevent HIV-1 infection are certain chemokines and also their receptors. In this case, the CCR5 binding chemokines include CCL3, CCL4, and also CCL5 have a function as the main natural factors that act as a suppressor of HIV-1 [49]. CCL3L1 up-regulation results in the down-regulation of CCR5 and following the internalization of receptor [50]. The trans-activating function of Tax protein 2 is attributed to an increased secretion of CCL3L1 [49]. During human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV)-1 and HTLV-2 infections with CCLs and CCRs, Tax1 and Tax2 may increase innate immunity in the extracellular environment, which may play a major role in regulating innate immunity during co-infection with HIV/ HTLV and inhibiting CCR5/HIV-1 [51]. The CCL3L1 down-regulates CCR5 for the entry of HIV-1, resulting in a long-term non-development status in co-infected patients with the high infection of HTLV-1 and 2 [52]. The most affected HTLV-1 cell is CD4+ T cell [53]. HTLV-1 and -2 are main co-pathogens among HIV-infected patients [54]. In this line, HTLV-2 and HTLV-1 infections can trigger the participation of innate HIV-1 immunity by modifying CCR5/HIV-1 binding and HIV-1 development in patients with co-infection [54]. In this regard, CCR5 down-regulation was reported for lymphocytes from HIV-1/HTLV-2 co-infected individuals [54]. High levels of co-infection with HIV-1/HTLV appear in HTLV-1-endemic regions, where HTLV-2 is transmitted by sharing the needle. In European and United States studies, individuals with HIV-1 and HTLV-2 co-infections were found to result in altered clinical outcomes, and also delayed development of AIDS [55, 56]. In contrast, there are several reports were indicated that co-infection with HTLV-1/HIV-1 is associated with faster AIDS clinical progression and shorter survival time and also have more risk to progress myelopathies as well as neurological disease [54, 55, 57, 58]. HTLV-I is widespread in a variety of geographic regions, including Japan, the Caribbean, South America, Africa and Northeastern Iran [59,60,61]. HTLV-I is endemic in five Iranian provinces such as Khorasan Razavi (Mashhad), Northern Khorasan, Alborz, Eastern Azarbayejan, and Golestan [61,62,63]. However, there is no report of co-infection HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infection with HIV in Mashhad in the general population [47, 64]. Rahimi et al. indicated that HTLV-I/HIV co-infection may stimulate HIV replication and also could decrease the HTLV-I viral load, in infected cells in non intraveneous drug users in Mashhad [62].

In addition to general and main key population, there is a low risk of HIV-1 infection for HIV-1 laboratory workers as we all health care workers that are prolonged laboratory exposure to concentrated HIV-1 and also exposure to experiencing needle stick injuries in clinical and laboratory research [65, 66]. It is suggested that strict biosafety level 3 containment as well as practices are needed for work with HIV-1, particularly concentrated HIV-1 [65]. Although the frequency of HIV in the general population is low, it is higher in the high-risky populations such as persons who inject drugs, prisoners, and sex-workers. In this regard, the laboratories dealing with the latter group of populations are exposed to danger. Moreover, the lack of biosafety level 3 containment is another risk factor. Thus, the laboratories and the staffs researching on HIV are at risk, and most of the staffs are not interested to work in such a risky environment due to unwanted incidents. So, it is reasonable to employ the staffs, carrying the mutation (CCR5∆32), for working in such risky environments and blood samples.

In addition, the bioinformatics analysis indicated that mutated proteins lost three alpha helices, as the results of this changes degraded in the cells. Nevertheless, modeling indicated that the truncated protein also have the required domains for virus attachment and these domains did not show major conformational alterations with the wild type ones, so we can conclude that displaying the truncated protein on the cell surface may be a possible way of virus entry [5]. Thus, defective protein destruction in the cell and the absence of its surface display can be the main reason for CCR5∆32 variants resistance. These findings can suggest strategies for combating against HIV infections based on the prevention of expression or surface display of CCR5 [67,68,69,70,71,72]. RNAi technology can be used to prevent of CCR5 expression or the masking of CCR5 on the cell surface which may be considered as research area to the prevention of HIV infection. Nowadays, various therapies are used to treat HIV-1 by targeting CCR5 receptors like CCR5 inhibitors. The CCR5 inhibitors include various agents such as maraviroc (MVC) (FDA approved), CMPD167, vicriviroc (VVC), aplaviroc (AVC), VCH-286, TAK-779, G-protein-coupled CCR5 receptors, zinc finger nucleases, and cell-specific RNA aptamer [73,74,75,76,77,78]. These inhibitors change the shape of CCR5 and inhibit HIV-1 entry to target cells by preventing the binding of viral protein gp120 to the CCR5 [70]. Moreover, it is indicated that introduction of the CCR5∆32/∆32 in induced pluripotent stem cells by the combination of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein nuclease (Cas)-9 system and a PiggyBac transposon lead to a resistance to the infection of HIV/AIDS. Moreover, a resistance was established by engineered induced pluripotent stem cells-derived phagocytic cells (monocytes and the macrophages) [67]. Based on the previous studies, a tropism-dependent resistance against HIV/AIDS infection is described in disrupts human CCR5 T-cells. In this line, in CCR5-modified cells, targeting of CCR5 via CRISPR-Cas9 technology, reduced tropic-dependent resistance against HIV-1/AIDS and has non-cytotoxic effect on the viability of cells [68, 71]. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 system packaged with lentiviral vectors exposed hopeful outcomes in reducing HIV-1 infection [69].

Conclusions

The CCR5∆32 allele plays a main role in the resistance to HIV-1 infection, as a natural selection allele, and also its distribution is used for geodetic survey data. Aside from its importance in the geographic distribution, the use of this mutation has brought new hope for eradicating HIV infection. Novel therapies have led to significant progress in the treatment of HIV-1 infection, whereas some side effects such as drug-drug interactions, substantial toxicity, difficulties in adherence, and increased cost remain. Therefore, with the knowledge of individuals’ genetic variations, the most efficient treatment could be chosen, which reduces drug costs and side effects with appropriate drug dosing. Furthermore, for the first time, our study revealed the low prevalence of this mutation in the normal population of North Eastern Iran (Khorasan Province) and consequently concluded that there is a HIV-1 infection. Therefore, in these areas, more attention and preventive steps should be taken to prevent HIV infection. In addition, based on the controversially results in studies, more investigation is needed to evaluate HTLV prevalence, especially HTLV-1 and its influence on the viral load of HIV as well as AIDS development in co-infected patients in endemic area such as Khorasan, Iran. Even though there are no findings of the prevalence co-infection with HTLV/HIV in Iran, which can due to low prevalence of HIV in this area, patients and healthy persons need screening for potential clinical manifestations, particularly neurological diseases. To our knowledge and based on the results of previous studies, we could not find any association between prevalence of HIV and HTLV-1 infection and CCR5∆32 in Iran. The complete and accurate information according to the prevalence of HIV can help health authorities to design more successful plans in the general population. Since the prevalence of HIV in this area remains low, the implementation of health policies, public awareness, free HIV counseling and testing services appear to have led to this low prevalence. Conclusively, these findings provide a new understanding for scientists to define future research in the field of immunobiology of HIV-1 in Iranian population.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. However, all samples and data are collected from the Mashhad cohort study (Grant number: 85134; Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Khorasan northeastern Iran (for more information see ref.: [12].

Abbreviations

- AVC:

-

Aplaviroc

- CCR5:

-

C-C chemokine receptor 5

- CCR5∆32 :

-

A 32-nucleotide deletion in the exon of CCR5 gene

- CCR5 ∆32/∆32 :

-

Heterozygote genotype for CCR5Δ32

- CRISPR-Cas9:

-

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated protein nuclease-9

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HIV-1:

-

HIV type 1

- HTLV:

-

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus

- MVC:

-

Maraviroc

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- R5-tropic:

-

CCR5-tropic

- VVC:

-

Vicriviroc

References

Taylor MFJ, Shen Y, Kreitman ME. A population genetic test of selection at the molecular-level. Science. 1995;270(5241):1497–9.

Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA, Cayanan C, Maddon PJ, Koup RA, Moore JP. HIV-1 entry into CD4 sup+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381(6584):673.

Liu R, Paxton WA, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin SR, Horuk R, MacDonald ME, Stuhlmann H, Koup RA, Landau NR. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86(3):367–77.

Ungvári I, Tölgyesi G, Semsei ÁF, Nagy A, Radosits K, Keszei M, Kozma GT, Falus A, Szalai C. CCR5Δ32 mutation, mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1545–7.

Michael NL, Chang G, Louie LG, Mascola JR, Dondero D, Birx DL, Sheppard HW. The role of viral phenotype and CCR-5 gene defects in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1997;3(3):338–40.

Bouhlal H, Latry V, Requena M, Aubry S, Kaveri SV, Kazatchkine MD, Belec L, Hocini H. Natural antibodies to CCR5 from breast milk block infection of macrophages and dendritic cells with primary R5-tropic HIV-1. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7202–9.

Oh D-Y, Jessen H, Kücherer C, Neumann K, Oh N, Poggensee G, Bartmeyer B, Jessen A, Pruss A, Schumann RR. CCR5Δ32 genotypes in a German HIV-1 seroconverter cohort and report of HIV-1 infection in a CCR5Δ32 homozygous individual. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2747.

Agrawal L, Lu X, Qingwen J, VanHorn-Ali Z, Nicolescu IV, McDermott DH, Murphy PM, Alkhatib G. Role for CCR5Δ32 protein in resistance to R5, R5X4, and X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary CD4+ cells. J Virol. 2004;78(5):2277–87.

Sandford AJ, Zhu S, Bai TR, FitzGerald JM, Paré PD. The role of the CC chemokine receptor-5 Δ32 polymorphism in asthma and in the production of regulated on activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(1):69–73.

Wu L, Paxton WA, Kassam N, Ruffing N, Rottman JB, Sullivan N, Choe H, Sodroski J, Newman W, Koup RA, et al. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;185(9):1681–91.

Hutter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Mussig A, Allers K, Schneider T, Hofmann J, Kucherer C, Blau O, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(7):692–8.

Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Moohebati M, Esmaily H, Ebrahimi M, Parizadeh SM, Heidari-Bakavoli AR, Safarian M, Mokhber N, Nematy M, Saber H, et al. Mashhad stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorder (MASHAD) study: design, baseline characteristics and 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(5):561–72.

Karakaya G, YILDIRAN FAB, ARICA ŞÇ. Investigation of the frequency of the mutant CCR5-Δ32 allele related to HIV resistance in Turkey. Turk J Med Sci. 2013;43(6):886–90.

Pham HT, Mesplede T. The latest evidence for possible HIV-1 curative strategies. Drugs in context. 2018;7:212522.

Novembre J, Galvani AP, Slatkin M. The geographic spread of the CCR5 Delta32 HIV-resistance allele. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(11):e339.

Nei M, Roychoudhury AK. Evolutionary relationships of human populations on a global scale. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10(5):927–43.

Galvani AP, Slatkin M. Evaluating plague and smallpox as historical selective pressures for the CCR5-Δ32 HIV-resistance allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15276–9.

Rahimi H, Farajollahi MM, Hosseini A. Distribution of the mutated delta 32 allele of CCR5 co-receptor gene in Iranian population. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:140.

Kortlandt F. The spread of the indo-Europeans. JIES. 1990;18:131–40.

Lucotte G. Distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion in West Europe. A hypothesis about the possible dispersion of the mutation by the Vikings in historical times. Hum Immunol. 2001;62(9):933–6.

Lucotte G, Dieterlen F. More about the Viking hypothesis of origin of the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene conferring resistance to HIV-1 infection. Infect Genet Evol. 2003;3(4):293–5.

Abousaidi H, Vazirinejad R, Arababadi MK, Rafatpanah H, Pourfathollah AA, Derakhshan R, Daneshmandi S, Hassanshahi G. Lack of association between chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) d32 mutation and pathogenesis of asthma in Iranian patients. South Med J. 2011;104(6):422–5.

Arababadi MK, Hassanshahi G, Azin H, Salehabad VA, Araste M, Pourali R, Nekhei Z. No association between CCR5-Δ32 mutation and multiple sclerosis in patients of southeastern Iran. Lab Medicine. 2010;41(1):31–3.

Shahbazi M, Ebadi H, Fathi D, Roshandel D, Mahamadhoseeni M, Rashidbaghan A, Mahammadi N, Mahammadi MR, Zamani M. CCR5-Delta32 allele is associated with the risk of developing multiple sclerosis in the Iranian population. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2009;29(8):1205–9.

Omrani D. Frequency of CCR5? 32 variant in north-west of Iran. J Sci I R Iran. 2009;20(2):105–10.

Gharagozloo M, Doroudchi M, Farjadian S, Pezeshki AM, Ghaderi A. The frequency of CCR5Delta32 and CCR2-64I in southern Iranian normal population. Immunol Lett. 2005;96(2):277–81.

Heydarifard Z, Tabarraei A, Moradi A. Polymorphisms in CCR5Δ32 and Risk of HIV-1 Infection in the Southeast of Caspian Sea, Iran. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:5.

Bineshian F, Hosseini A, Sharifi Z, Aghaie A. A study on the association between CCRΔ32 mutation and HCV infection in Iranian patients. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2018;10(4):261–4.

Abdolmohammadi R, Shahbazi Azar S, Khosravi A, Shahbazi M. CCR5 polymorphism as a protective factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-infected Iranian patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(10):4643–6.

Amirshahi P, Sunderland E, Farhud D, Daneshmand P, Papiha S. Population genetics of the peoples of Iran I. Genetic polymorphisms of blood groups, serum proteins and red cell enzymes. Int J Anthropol. 1992;7:1–10.

Derenko M, Malyarchuk B, Bahmanimehr A, Denisova G, Perkova M, Farjadian S, Yepiskoposyan L. Complete mitochondrial DNA diversity in Iranians. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80673.

Mehrjoo Z, Fattahi Z, Beheshtian M, Mohseni M, Poustchi H, Ardalani F, Jalalvand K, Arzhangi S, Mohammadi Z, Khoshbakht S, et al. Distinct genetic variation and heterogeneity of the Iranian population. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(9):e1008385.

Farjadian S, Ghaderi A. Iranian Lurs genetic diversity: an anthropological view based on HLA class II profiles. Iran J Immunol. 2006;3(3):106–13.

Ongadi B, Obiero G, Lihana R, Kiiru J. Distribution of genetic polymorphism in the CCR5 among Caucasians, Asians and Africans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open J Genet. 2018;08:54–66.

Hutter G, Bluthgen C, Elvers-Hornung S, Kluter H, Bugert P. Distribution of the CCR5-delta32 deletion in Southwest Germany. Anthropol Anz. 2015;72(3):303–9.

Martinson JJ, Chapman NH, Rees DC, Liu YT, Clegg JB. Global distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion. Nat Genet. 1997;16(1):100–3.

Silva-Carvalho WH, de Moura RR, Coelho AV, Crovella S, Guimaraes RL. Frequency of the CCR5-delta32 allele in Brazilian populations: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;43:101–7.

Husain S, Goila R, Shahi S, Banerjea A. First report of a healthy Indian heterozygous for delta 32 mutant of HIV-1 co-receptor-CCR5 gene. Gene. 1998;207(2):141–7.

Jawdat D, Alarifi M, Al-Turki A, Alalwan A, Al-Amro F, Atallah N, Muallimi MA, Al-Balwi M, Hajeer A. 82-p: the prevalence of CCR5 delta 32 mutation in Saudi Arabia. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:108.

Balci A, Yegin Z, Koc H. Prevalence of HIV/AIDS protective alleles (CCR5-Δ32, CCR2-64I, and SDF1-3’A) in Turkish population. Res J Biol. 2017;5(2):36-42.

Solloch UV, Lang K, Lange V, Böhme I, Schmidt AH, Sauter J. Frequencies of gene variant CCR5-Δ32 in 87 countries based on next-generation sequencing of 1.3 million individuals sampled from 3 national DKMS donor centers. Hum Immunol. 2017;78(11):710–7.

UNAIDS. 2019 Global AIDS update: communities at the Centre. United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2019. AIDSinfo website. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-global-AIDS-update. Accessed July 2019 aahauoUC.

Sharifi H, Mirzazadeh A, Shokoohi M, Karamouzian M, Khajehkazemi R, Navadeh S, Fahimfar N, Danesh A, Osooli M, McFarland W, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence and its trend in three key populations in Iran. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207681.

Bagheri Amiri F, Mostafavi E, Mirzazadeh A. HIV, HBV and HCV Coinfection prevalence in Iran--a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151946.

Haghdoost A, Mostafavi E, Mirzazadeh A, Sajadi L, Navadeh S, Feizzadeh A, Fahimfar N, Kamali K, Namdari H, Sedaghat A. Modelling of HIV/AIDS in Iran up to 2014. J AIDS HIV Res. 2011;3:231–9.

Moradi G, Piroozi B, Alinia C, Akbarpour S, Gouya M, Saadi S, Mohamadi A, Kazaerooni P. Incidence, mortality, and burden of HIV/AIDS and its geographical distribution in Iran during 2008-2016. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48:1–9.

Miri R, Ahmadi Ghezeldasht S, Mosavat A, Hedayati-Moghaddam MR. No evidence of HIV infection among the general population of Mashhad, Northeast of Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2017;10(3):e43655.

Rezvan H, Abolghassemi H, Kafiabad SA. Transfusion-transmitted infections among multitransfused patients in Iran: a review. Transfus Med. 2007;17(6):425–33.

Pilotti E, Bianchi MV, De Maria A, Bozzano F, Romanelli MG, Bertazzoni U, Casoli C. HTLV-1/−2 and HIV-1 co-infections: retroviral interference on host immune status. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:372.

Townson JR, Barcellos LF, Nibbs RJ. Gene copy number regulates the production of the human chemokine CCL3-L1. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(10):3016–26.

Oo Z, Barrios CS, Castillo L, Beilke MA. High levels of CC-chemokine expression and downregulated levels of CCR5 during HIV-1/HTLV-1 and HIV-1/HTLV-2 coinfections. J Med Virol. 2015;87(5):790–7.

Pilotti E, Elviri L, Vicenzi E, Bertazzoni U, Re MC, Allibardi S, Poli G, Casoli C. Postgenomic up-regulation of CCL3L1 expression in HTLV-2–infected persons curtails HIV-1 replication. Blood. 2006;109(5):1850–6.

Rahimzadegan M, Abedi F, Rezaei SA, Ghadimi R. HTLV-1: ancient virus, new challenges. Rev Clin Med. 2014;1(3):141–8.

Beilke MA. Retroviral coinfections: HIV and HTLV: taking stock of more than a quarter century of research. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2012;28(2):139–47.

Beilke MA, Theall KP, O'Brien M, Clayton JL, Benjamin SM, Winsor EL, Kissinger PJ. Clinical outcomes and disease progression among patients coinfected with HIV and human T lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(2):256–63.

Turci M, Pilotti E, Ronzi P, Magnani G, Boschini A, Parisi SG, Zipeto D, Lisa A, Casoli C, Bertazzoni U. Coinfection with HIV-1 and human T-Cell lymphotropic virus type II in intravenous drug users is associated with delayed progression to AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2006;41(1):100–6.

Brites C, Alencar R, Gusmao R, Pedroso C, Netto EM, Pedral-Sampaio D, Badaro R. Co-infection with HTLV-1 is associated with a shorter survival time for HIV-1-infected patients in Bahia, Brazil. Aids. 2001;15(15):2053–5.

Isache C, Sands M, Guzman N, Figueroa D. HTLV-1 and HIV-1 co-infection: a case report and review of the literature. IDCases. 2016;4:53–5.

Hedayati-Moghaddam MR, Fathimoghadam F, Eftekharzadeh Mashhadi I, Soghandi L, Bidkhori HR. Epidemiology of HTLV-1 in Neyshabour, northeast of Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(6):424–7.

Proietti FA, Carneiro-Proietti AB, Catalan-Soares BC, Murphy EL. Global epidemiology of HTLV-I infection and associated diseases. Oncogene. 2005;24(39):6058–68.

Rafatpanah H, Hedayati-Moghaddam MR, Fathimoghadam F, Bidkhori HR, Shamsian SK, Ahmadi S, Sohgandi L, Azarpazhooh MR, Rezaee SA, Farid R, et al. High prevalence of HTLV-I infection in Mashhad, Northeast Iran: a population-based seroepidemiology survey. J Clin Virol. 2011;52(3):172–6.

Rahimi H, Rezaee SA, Valizade N, Vakili R, Rafatpanah H. Assessment of HTLV-I proviral load, HIV viral load and CD4 T cell count in infected subjects; with an emphasis on viral replication in co-infection. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17(1):49–54.

Kalavi K, Moradi A, Tabarraei A. Population-based Seroprevalence of HTLV-I infection in Golestan Province, south east of Caspian Sea, Iran. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16(3):225–8.

Rafatpanah H, Fathimoghadam F, Shahabi M, Eftekharzadeh I, Hedayati-Moghaddam M, Valizadeh N, Tadayon M, Shamsian SA, Bidkhori H, Miri R, et al. No evidence of HTLV-II infection among Immonoblot indeterminate samples using nested PCR in Mashhad, northeast of Iran. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16(3):229–34.

Weiss SH, Goedert JJ, Gartner S, Popovic M, Waters D, Markham P, di Marzo VF, Gail MH, Barkley WE, Gibbons J, et al. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection among laboratory workers. Science (New York, NY). 1988;239(4835):68–71.

Soria A, Alteri C, Scarlatti G, Bertoli A, Tolazzi M, Balestra E, Bellocchi MC, Continenza F, Carioti L, Biasin M, et al. Occupational HIV infection in a research laboratory with unknown mode of transmission: a case report. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(6):810–3.

Ye L, Wang J, Beyer AI, Teque F, Cradick TJ, Qi Z, Chang JC, Bao G, Muench MO, Yu J, et al. Seamless modification of wild-type induced pluripotent stem cells to the natural CCR5Delta32 mutation confers resistance to HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(26):9591–6.

Liu Z, Chen S, Jin X, Wang Q, Yang K, Li C, Xiao Q, Hou P, Liu S, Wu S, et al. Genome editing of the HIV co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by CRISPR-Cas9 protects CD4(+) T cells from HIV-1 infection. Cell Biosci. 2017;7:47.

Choi JG, Dang Y, Abraham S, Ma H, Zhang J, Guo H, Cai Y, Mikkelsen JG, Wu H, Shankar P, et al. Lentivirus pre-packed with Cas9 protein for safer gene editing. Gene Ther. 2016;23(7):627–33.

Berro R, Klasse PJ, Moore JP, Sanders RW. V3 determinants of HIV-1 escape from the CCR5 inhibitors Maraviroc and Vicriviroc. Virology. 2012;427(2):158–65.

Xiao Q, Chen S, Wang Q, Liu Z, Liu S, Deng H, Hou W, Wu D, Xiong Y, Li J, et al. CCR5 editing by Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 in human primary CD4+ T cells and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells promotes HIV-1 resistance and CD4+ T cell enrichment in humanized mice. Retrovirology. 2019;16(1):15.

Xie Y, Zhan S, Ge W, Tang P. The potential risks of C-C chemokine receptor 5-edited babies in bone development. Bone Research. 2019;7(1):4.

Li L, Krymskaya L, Wang J, Henley J, Rao A, Cao L-F, Tran C-A, Torres-Coronado M, Gardner A, Gonzalez N. Genomic editing of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 in adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using zinc finger nucleases. Mol Ther. 2013;21(6):1259–69.

Berro R, Yasmeen A, Abrol R, Trzaskowski B, Abi-Habib S, Grunbeck A, Lascano D, Goddard WA, Klasse PJ, Sakmar TP, et al. Use of G-protein-coupled and -uncoupled CCR5 receptors by CCR5 inhibitor-resistant and -sensitive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants. J Virol. 2013;87(12):6569–81.

Asin-Milan O, Sylla M, El-Far M, Belanger-Jasmin G, Blackburn J, Chamberland A, Tremblay CL. Synergistic combinations of the CCR5 inhibitor VCH-286 with other classes of HIV-1 inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7565–9.

Briz V, Poveda E, Soriano V. HIV entry inhibitors: mechanisms of action and resistance pathways. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57(4):619–27.

Malcolm RK, Veazey RS, Geer L, Lowry D, Fetherston SM, Murphy DJ, Boyd P, Major I, Shattock RJ, Klasse PJ, et al. Sustained release of the CCR5 inhibitors CMPD167 and maraviroc from vaginal rings in rhesus macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2251–8.

Zhou J, Satheesan S, Li H, Weinberg MS, Morris KV, Burnett JC, Rossi JJ. Cell-specific RNA aptamer against human CCR5 specifically targets HIV-1 susceptible cells and inhibits HIV-1 infectivity. Chem Biol. 2015;22(3):379–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Majid Ghayour-Mobarhan for his helps by giving us samples.

Funding

This manuscript was financially supported by the Mashhad University of Medical Science (Grant Number: 930623).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT: Conception and design, data collection, extraction of genomic DNA, genome genotyping, data analysis and writing the manuscript. MF: Data collection, extraction of genomic DNA, genome genotyping, statistical analysis, writing the manuscript. MR: Critical review, manuscript approval, figure design. FGh: Conception and design. AGh: Critical review, manuscript approval. ZM: Conception and design, supervision of the Project, approval of the manuscript, Overall responsibility. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mashhad university of science (ethical approval code: IR.MUMS.REC.1393.964).

In this respect, written informed consent has been received from all participants.

Consent for publication

A written informed consent form was signed by all individuals whose data is described.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tajbakhsh, A., Fazeli, M., Rezaee, M. et al. Prevalence of CCR5delta32 in Northeastern Iran. BMC Med Genet 20, 184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-019-0913-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-019-0913-9