Abstract

Background

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) account for a disproportionate number of new HIV infections worldwide. HIV prevalence among young sex workers in Uganda is 22.5%. Although pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly effective biomedical HIV prevention method, awareness of PrEP among AGYW in Uganda has not been studied systematically. We aimed to assess awareness of PrEP and factors associated with awareness of PrEP among AGYW who frequently reported paid sex.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among 14–24-year old AGYW at high risk of HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda from January to October 2019. Participants were screened for PrEP eligibility using a national screening tool of whom 82.3% were eligible. Data on socio-demographics, behavioral and sexual risks were collected by interview. Awareness of oral or injectable PrEP, the latter of which is currently in late-stage trials, was defined as whether an individual had heard about PrEP as an HIV prevention method. Multivariable robust poisson regression model was used to assess factors associated with oral PrEP awareness.

Results

We enrolled 285 participants of whom 39.3% were under 20 years old, 54.7% had completed secondary education, 68.8% had multiple sex partners in the past 3 months, 8.8% were screened as high risk drinkers’/ alcohol dependent (AUDIT tool) and 21.0% reported sex work as main occupation. Only 23.2% were aware of oral PrEP and 3.9% had heard about injectable PrEP. The prevalence of oral PrEP awareness was significantly higher among volunteers screened as alcohol dependents (aPR 1.89, 95% CI 1.08–3.29) and those with multiple sexual partners (aPR 1.84, 95% CI 1.01–3.35), but was lower among those who reported consistent condom use with recent sexual partners (aPR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91).

Conclusions

Majority of AGYW were not aware of any kind of PrEP. Those with higher risk behavior, i.e. alcohol dependents or multiple sexual partners, were more aware of oral PrEP. Interventions to increase awareness among female youth are needed. Improving PrEP awareness is critical to increasing PrEP uptake among high-risk AGYW in Uganda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although various HIV prevention interventions (biomedical, behavioral and structural) have mitigated the spread of HIV [1], the number of new cases among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) remains unacceptably high [2, 3]. In 2019, an estimated 1.7 million adolescents aged 10–19 years were living with HIV across the globe of whom 10% were newly infected [4]. In sub-saharan Africa, AGYW account for 24% of new HIV infections [5] with an estimated HIV prevalence four times higher than their male peers [4, 5]. Additionally, about 5,000 AGYW aged 15–24 years are newly infected with HIV every week [5, 6]. In Eastern and Southern Africa alone, AGYW accounted for 26% of new infections in 2019 [5]. In Uganda, the prevalence of HIV among adolescent sex workers is 22.5% [7]. Most of these are involved in high-risk sexual behavior including sex work and having multiple partners, which has accelerated the spread of HIV in this age group.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to reduce the number of new HIV infections among high-risk populations [8], and many national programs have adopted this biomedical HIV prevention strategy [9]. Recent long-acting injectable PrEP findings have shown that it is safe and highly effective [10]. Additionally there many products in the pipeline that are being evaluated for example the PrEP Implant [11]. It is essential that awareness of these methods are built early at the population level. In 2018, of the 3 million people at substantial risk of HIV [12], only 381,580 people were taking oral PrEP worldwide. Of these, only 27% were from sub-saharan Africa with a majority of these PrEP users being AGYW [13]. By July 2020, an estimated 31,000–32,000 people were using PrEP in Uganda, which was lower than the Ministry of Health target of 90,000 people at risk [14].

PrEP is highly effective when adherence is good [15, 16]. A sub study among partners in East Africa, found that high PrEP adherence (> 80%) was associated with 100% PrEP efficacy [17]. However, there is limited awareness of oral PrEP as an HIV prevention method among populations at high risk for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa despite years of science and nascent programs to provide it [18]. The prevalence of PrEP awareness among AGYW remains unknown within Uganda [19] and poor uptake has been reported [18, 20]. Awareness of novel HIV prevention methods among key populations remains important as it will likely motivate uptake and adherence to future prevention products. We therefore need to improve understanding of awareness of both available and future HIV prevention methods. Literature suggests that most individuals at risk support PrEP usage once provided with details on its use and efficacy [21]. Additionally a study among adolescents in the US reported that many persons at risk do not know how to access oral PrEP even if they are aware that they need it [22]. A recent study among AGYW in South Africa found that only 19% were aware of PrEP, and family support and discussing HIV and sexually transmitted infections with sexual partners were associated factors for PrEP awareness [2]. Also, a recent study among Black and Latinx adolescents in the US residing in higher prevalence areas revealed that only 38% knew about PrEP [23].

In recent clinical trials, injectable PrEP has proven to be 89% more effective than oral PrEP [10] and will likely be available as a prevention tool soon. Raising awareness of oral or injectable PrEP is a first and necessary step to increase their use among at-risk AGYW, yet data is still limited in Uganda. Since 2015, the Determined Resilient Empowered AIDS-free Mentored and Safe women (DREAMS) project was implementing a package of HIV prevention services including PrEP provision to AGYW in selected districts of Uganda [24,25,26]. Also, at the time we enrolled the cohort of AGYW, the Ministry of Health in Uganda was conducting trainings for health workers and rolling out oral PrEP to selected key populations and, 3 clinical trial sites in Uganda were enrolling for the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN084) trial to compare efficacy of long acting injectable cabotegravir to daily oral Truvda [10, 27]. The aim of our study was to determine awareness of oral and injectable PrEP, and to assess factors associated with awareness of oral PrEP among high-risk AGYW in Kampala, Uganda.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of PrEP awareness and associated factors measured from baseline data for a two-year cohort study. Between January and October 2019, 14–24-year-old AGYW were recruited from commercial hotspots (i.e., where sex work is prevalent) and slums of southern and northern Kampala, and invited to enroll into a cohort of AGYW at the Good Health for Women Project (GHWP) clinic located in a peri-urban community in southern Kampala [28]. The clinic offered HIV prevention and care services, free general health care and reproductive health services to eligible high-risk women including female sex workers (FSWs).

Study population and sampling design

The national risk screening tool (evaluates risk in the last 6 months) given by the Ministry of Health (MoH) was used to assess if participants were at high risk for HIV: (i) Being sexually active with at least one of the following i.e. condomless sex with multiple partners, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and use of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP); (ii) sharing injections; (iii) and having an HIV positive sexual partner who is not on effective antiretroviral therapy (ART). PrEP Eligibility was then determined by having a positive HIV test and a positive response to any of the risk factors in the MoH risk screening tool.

Eligible Participants were then enrolled into the parent cohort study that was assessing knowledge and preferences of biomedical HIV prevention methods, and uptake of oral PrEP among at-risk 14-to-24-year-old females in Kampala. AGYW were enrolled in the cohort if they were HIV negative, Hepatitis B immune (through prior infection or vaccination) or willing to be vaccinated if susceptible, sexually active in the past 3 months, willing to use effective contraceptive methods, undergo regular HCT, pregnancy testing, and screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Participants were excluded if pregnant or planning pregnancy in the next 12 months; had known allergy to components of oral PrEP drugs, contraceptives or Hepatitis B vaccine; and reported or were diagnosed with an illness that would affect participation in the study.

Data collection

Trained research assistants collected data using standardized paper questionnaires administered face-to-face. We collected data on socio-demographic and risk behavior (i.e.: number of sexual partners; transactional, anal, group or forced sex; condom use with sexual partners; knowledge of sexual partners’ HIV status; and having STIs). Data were double entered into an Open Clinica database by trained data entrants. Discrepancies were resolved by referring back to the source documents.

Study variables

Primary outcome

Awareness of Oral PrEP was the primary outcome in this study and was measured as a binary variable (Yes/No). As a secondary outcome, awareness of injectable PrEP (a hypothetical product still in clinical trials at the time of this study) was also measured as a binary variable (Yes/No).

Volunteers were also assessed on; (1) their knowledge about of oral and injectable PrEP (Pills were demonstrated using samples at site), (2) the primary source of information for those who reported prior knowledge about these methods and (3) willingness to use these methods after explaining their benefits and frequency of use.

Independent variables included the following: socio-demographics factors included age, highest level of education (below or above primary level), marital status (married, separated, widowed, or single) and main occupation (sex work, no job, other).

Behavioural risk factors included alcohol consumption risk level and drug use. Drug use was defined as use of any illicit drugs in the past 1 month. Alcohol consumption risk level was based on the score of the Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) questionnaire [29]. Participants were categorised as low risk (AUDIT score < 8), moderate risk/hazardous (AUDIT score 8–19), and high risk/ dependent (AUDIT score ≥ 20).

Sexual risk factors included age at first sex, number of sexual partners in the past 3 months, consistent condom use with sexual partners in the past 3 months, transactional sex (receiving and/ or giving money and goods for sex), history of STI symptoms (abnormal discharge and/ or genital ulcer), frequent traveling away from home in the past 3 months and current contraceptive use.

Statistical analysis

We analysed data using Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Baseline characteristics of the participants were summarised using frequencies and proportions. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess associations with awareness of oral PrEP. Univariable robust poisson regression was used to estimate crude prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables significant at p < 0.1 and those hypothesized to be associated with the outcome based on prior knowledge (i.e., condom use, age and level of education) were selected for inclusion in a multivariable robust poisson regression model. We also tested for collinearity and for the variables that were found to be highly correlated i.e. drug use and alcohol use [30] only one of these was selected and included in the final model. The final model was selected based on variables that were found to be independently associated (P < 0.05) with the outcome. After fitting the final model, adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% CIs were obtained and reported.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee (GC/127/18/06/658) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS2435). Participants gave written informed consent before being enrolled.

Results

Baseline characteristics

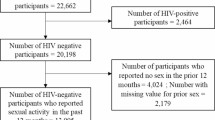

We screened 532 AGYW for both study participation and PrEP eligibility, 94 were not eligible for PrEP due to: HIV sero-positivity [29], not sexually active in the past 3 months [51], hepatitis B infection [10] and abnormal kidney function tests [4]. Of the rest, 153 were not eligible for the study due to: study sample size being achieved (93) and unwillingness to return for follow up procedures and other reasons (60). We therefore enrolled 285 AGYW (all PrEP eligible) and all were included in our analysis. The mean age was 19.9 (SD ± 2.24) years; 39.3% (112) were younger than 20 years old (Table 1); 54.7% had completed secondary education or greater; 57.2% were single and while 92.6% engaged in transactional sex, 21.0% reported sex work as their main occupation. The proportion of participants that were alcohol dependent based on the audit score, reported illicit drug use in the past one month, and reported frequent travelling away from home during the last 3 months were 8.8%, 84.6%, and 40.0%, respectively. Additionally, 80.0% of the participants had their first sexual encounter before the age of 18 years; 68.8% had multiple sexual partners and 73.3% reported consistent condom use in the last 3 months. The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) i.e. chlamydia, gonorrhoea was 25.3%

Awareness of oral and injectable PrEP

The prevalence of oral PrEP awareness was 23.2% (95% CI 18.4–28.5) while that of injectable PrEP was at 3.9% (95% CI 1.94–6.8), 6 participants had heard of both methods. Sources of oral PrEP information included peers (54.6%), health workers (42.4%), media (7.6%), other (3.0%) and community leaders (1.5%) while sources for injectable PrEP information were peers 8 (72.7%), heath workers 3 (27.3%) and media 1 (9.1%).

Oral PrEP awareness was significantly higher among participants with more than one sexual partner compared to those with only one sexual partner (27.6% vs 13.5%; p = 0.009). Additionally, alcohol dependents were more aware about PrEP compared to the low risk drinkers. (48.0% vs 19.4%; p = 0.006) (Table 1).

Willingness to use oral and injectable PrEP

Following an explanation of the details of PrEP and its potential benefits, majority of the participants 256 (89.8%) and 255 (89.5%) were willing to use either oral or injectable PrEP respectively. The high pill burden was the main reason for non-willingness to use oral PrEP (22, 75.9%), whereas non-willingness for injectable PrEP usage was majorly explained by the fear of potential side effects (12, 40.0%).

Factors associated with awareness of oral PrEP

In the adjusted analysis (Table 2), the prevalence of oral PrEP awareness was higher among participants who screened as alcohol dependent based on the AUDIT tool compared to those who were not (aPR 1.89, 95% CI 1.08–3.29). Also, the prevalence ratio comparing participants who reported multiple sexual partners to those with only one sexual partner was 1.84 (aPR 1.84, 95% CI 1.01–3.35). The prevalence of oral PrEP awareness was lower among participants who reported consistent condom use compared to those who did not use condoms with sexual partners in the past 3 months (aPR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91).

Due to small numbers aware of injectable PrEP, we did not assess for factors associated with awareness of injectable PrEP, therefore the data for injectable PrEP are not presented in tables.

Discussion

We found only one in four AGYW participants had heard about oral PrEP, and fewer than one in twenty had ever heard about injectable PrEP, a hypothetical intervention still in clinical trials at the time of this study. Peer interactions contributed more to awareness of oral and injectable PrEP when compared to other sources such as health workers and media.

We also found that most of the AGYW reported being willing to use either oral or injectable PrEP after being educated about these methods, including details on the mode of administration, frequency of use, and the fact that the drugs have been found effective in preventing HIV infection. Alcohol consumption risk, number of sexual partners and condom use were associated with Oral PrEP awareness. Our findings are consistent with other studies in sub-Saharan Africa, which have reported low oral PrEP awareness among high-risk populations [2, 18, 20, 31, 32]. This finding could explain the observed low uptake of oral PrEP in the early oral PrEP implementation phase in several communities [33]. Also within these diverse communities, there have been few awareness campaigns, which could also explain the low uptake [2, 34]. On the other hand, low awareness of oral and injectable PrEP may be attributed to the fact that these prevention methods are new and have not been fully appreciated within these communities [35]. Future HIV prevention interventions should leverage on peer to peer networks to not only increase awareness about oral PrEP and other new HIV prevention methods but to also influence uptake and adherence.

Participants with multiple sexual partners had a higher prevalence of oral PrEP awareness. Previous studies have reported similar findings [36, 37]. Since exposure to multiple partners places individuals at higher risk of acquiring different diseases including HIV, individuals involved in such practice may be more likely to search for methods to protect themselves and this could explain the higher PrEP awareness we observe within this group in the current study. Also, it is likely that those with multiple sexual partners may have deeper social and peer-based networks, perhaps increasing their access to sources of information for health including PrEP [38].

The prevalence of oral PrEP awareness was higher among non-condom users. This is similar to results reported from a study in Kenya that assessed PrEP awareness among AGYW [39]. One reason for this would be misconceptions about condom use that drives the search for alternative methods of protection other than condoms within this group of individuals [40, 41]. Furthermore, it is likely that non-condom users just do not like condoms or cannot use condoms because sexual partners may control condom use in a relationship [42, 43]. Non condom users may therefore be driven by the need to protect themselves from HIV to search for and learn about alternative novel methods such as oral PrEP. Oral PrEP has been identified as a more user friendly and user-controlled method for AGYW and likely a suitable alternative for those who may not have skills to negotiate condom use with sexual partners [44]. Also, those who do not use condoms are likely to be more aware of PrEP in this population with a high prevalence of transactional sex. In our study setting, female sex workers are often offered higher fees by their clients in return for condomless sex [45]. This might explain why some participants prefer not to use condoms. In such circumstances, the need to protect themselves could lead them to search for or learn about more discrete methods that are not partner controlled e.g. oral PrEP [46, 47].

While our study suggests higher PrEP awareness among AGYW with alcohol dependence, other studies have reported PrEP awareness to be lower among persons with alcohol dependence compared to low risk alcohol consumers [36]. The majority of volunteers (> 90%) in our study engaged in transactional sex; alcohol consumption in this context occurs within sex work venues such as bars and nightclubs often as a way of coping with sex work [48]. It is possible that during the national oral PrEP roll out, the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders prioritized oral PrEP educational interventions in locations where key populations congregated, e.g., bars and nightclubs [49].

Peer influence was a key contextual factor contributing to awareness of oral PrEP. Peers with whom AGYW interacted were also potential sources of information about oral PrEP. Future HIV prevention interventions should leverage on peer to peer networks to not only increase awareness about oral PrEP but to influence uptake and adherence.

Alcohol dependent individuals tended to spend a long time away from their homes, which exposes them to meeting new people who may become sexual partners [50]. This is consistent with results reported by several studies that have indicated a correlation between alcohol dependency and high-risk sexual behavior among young people [51, 52] and older populations at risk [53, 54]. If aware of such risk, persons dependent upon alcohol may be more aware of the available methods that may protect them from contracting HIV.

Our study has three main limitations. First, this study focused on AGYW at risk within peri-urban areas and results may not be generalizable to at-risk AGYW found in rural areas and other regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Second, it was a cross-sectional study and so we were only able to assess the association between factors and PrEP awareness but could not establish causal directions. Last, the questionnaire assessed the source of PrEP awareness but did not collect information on whether the participant sought this knowledge for themselves or received it passively hence speculating on the reasons for the noted associations. Despite these limitations, our study was the first in Uganda to show that oral PrEP awareness remains low among this AGYW at high risk of HIV infection.

Conclusion

Promoting awareness for new effective HIV prevention tools among high risk AGYW is critical and should be conducted in a timely manner. In addition, this needs to be scaled up to potentially impact demand, uptake and adherence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AGYW:

-

Adolescent girls and young women

- PrEP:

-

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol use disorders identification test

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PR:

-

Prevalence ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- FSW:

-

Female sex worker

- HCT:

-

HIV counselling and testing

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted disease

- GHWP:

-

Good Health for Women Project

- UNCST:

-

Uganda National Council for Science and Technology

- UVRI-REC:

-

Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee

- MoH:

-

Ministry of Health

References

Hosek S, Pettifor A. HIV prevention interventions for adolescents. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(1):120–8.

Ajayi AI, Mudefi E, Yusuf MS, Adeniyi OV, Rala N, Goon DT. Low awareness and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescents and young adults in high HIV and sexual violence prevalence settings. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(43): e17716.

Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, McConnell M, van Rooyen H, Bekker L-G, Kurth A, et al. Rethinking HIV prevention to prepare for oral PrEP implementation for young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4 Suppl 3):20227.

UNICEF. UNICEF Data: Adolescent HIV prevention.. https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/. 2020. Accessed December 2020

UNAIDS. GLOBAL AIDS UPDATE: Seizing the moment-Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/global-aids-report. 2020. Accessed December 2020.

UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics—2020 fact sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. 2020. Accessed December 2020.

Swahn MH, Culbreth R, Salazar LF, Kasirye R, Seeley J. Prevalence of HIV and associated risks of sex work among youth in the slums of Kampala. AIDS Res Treat. 2016;2016:5360180.

WHO. World Health Organization Consolidated Guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care for key populations: 2016 update. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations-2016/en/.2016 Update. Accessed December 2020.

Hodges-Mameletzis I, Dalal S, Msimanga-Radebe B, Rodolph M, Baggaley R. Going global: the adoption of the World Health Organization’s enabling recommendation on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Sex Health. 2018;15(6):489–500.

WHO. Trial results reveal that long-acting injectable cabotegravir as PrEP is highly effective in preventing HIV acquisition in women. https://www.who.int/news/item/09-11-2020-trial-results-reveal-that-long-acting-injectable-cabotegravir-as-prep-is-highly-effective-in-preventing-hiv-acquisition-in-women 2020. Accessed January 2021.

Barrett SE, Teller RS, Forster SP, Li L, Mackey MA, Skomski D, et al. Extended-duration MK-8591-eluting implant as a candidate for HIV treatment and prevention. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(10):e01058-e1118.

UNAIDS. GLOBAL AIDS UPDATE:MILES TO GO. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/miles-to-go_en.pdf. 2018. Accessed August 2020.

NAM. National AIDS Manual. 380,000 people on PrEP globally, mostly in the USA and Africa. 2018. https://www.aidsmap.com/news/oct-2018/380000-people-prep-globally-mostly-usa-and-africa-updated. Accessed August 2020.

AVAC. AIDS vaccine advocacy coalition: PrEP watch. https://www.prepwatch.org/country/uganda. 2020. Accessed January 2020.

Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–9.

Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973–83.

Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, Wangisi J, Katabira E, Ronald A, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9): e1001511.

Irungu EM, Baeten JM. PrEP rollout in Africa: status and opportunity. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):655–64.

Jjuuko BN. Adolescent girls and young women at risk of HIV need access to PrEP. https://www.avac.org/sites/default/files/u3/Bridget_policyBrief_july2019.pdf. 2019. Accessed February 2021.

Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(2):102–10.

Koechlin FM, Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, O’Reilly KR, Baggaley R, Grant RM, et al. Values and preferences on the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among multiple populations: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1325–35.

Macapagal K, Kraus A, Korpak AK, Jozsa K, Moskowitz DA. PrEP awareness, uptake, barriers, and correlates among adolescents assigned male at birth who have sex with males in the US. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(1):113–24.

Taggart T, Liang Y, Pina P, Albritton T. Awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among Black and Latinx adolescents residing in higher prevalence areas in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7): e0234821-e.

Birdthistle I, Schaffnit SB, Kwaro D, Shahmanesh M, Ziraba A, Kabiru CW, et al. Evaluating the impact of the DREAMS partnership to reduce HIV incidence among adolescent girls and young women in four settings: a study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):912.

Saul J, Bachman G, Allen S, Toiv NF, Cooney C, Beamon TA. The DREAMS core package of interventions: a comprehensive approach to preventing HIV among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12): e0208167.

USAID. DREAMS: partnership to reduce HIV/Aids in adolescent girls and young women. https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/hiv-and-aids/technical-areas/dreams 2021. Accessed March 2022.

PEPFAR. HPTN 084: a phase 3 double blind safety and efficacy study of long-acting injectable cabotegravir compared to daily oral TDF/FTC for pre-exposure prophylaxis in HIV-uninfected women. https://ug.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/42/Juliet-Mpendo_UVRI-IAVI_HPTN084.pdf 2021. Accessed March 2022.

Vandepitte J, Bukenya J, Weiss HA, Nakubulwa S, Francis SC, Hughes P, et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of women involved in high-risk sexual behavior in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(4):316–23.

World Health O. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test : guidelines for use in primary health care / Thomas F. Babor et al. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Falk D, Yi H-Y, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and drug use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(2):100–10.

Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, Lafort Y, Gichangi P, Masvawure TB, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre- and post-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) among female and male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: implications for integrating biomedical prevention into sexual health services. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(2):141–53.

Yi S, Tuot S, Mwai GW, Ngin C, Chhim K, Pal K, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21580.

Koss C, Charlebois E, Ayieko J, Kwarisiima D, Kabami J, Balzer L, et al. Uptake, engagement, and adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis offered after population HIV testing in rural Kenya and Uganda: 72-week interim analysis of observational data from the SEARCH study. Lancet HIV. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30433-3.

Dunbar M, Kripke K, Haberer J, Castor D, Dalal S, Mukoma W, et al. Understanding and measuring uptake and coverage of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH18061.

Wheelock A, Eisingerich AB, Gomez GB, Gray E, Dybul MR, Piot P. Views of policymakers, healthcare workers and NGOs on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a multinational qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001234.

Garnett M, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Franks J, Hayes-Larson E, El-Sadr WM, Mannheimer S. Limited awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York city. AIDS Care. 2018;30(1):9–17.

Brooks RA, Landrian A, Lazalde G, Galvan FH, Liu H, Chen Y-T. Predictors of awareness, accessibility and acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among English- and Spanish-speaking Latino men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(4):708–16.

Bingenheimer JB, Asante E, Ahiadeke C. peer influences on sexual activity among adolescents in Ghana. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(1):1–19.

Sila J, Larsen AM, Kinuthia J, Owiti G, Abuna F, Kohler PK, et al. High awareness, yet low uptake, of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent girls and young women within family planning clinics in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(8):336–43.

Elshiekh HF, Hoving C, de Vries H. Exploring determinants of condom use among university students in Sudan. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(4):1379–91.

Ochieng M, Kakai R, Abok K. Knowledge, attitude and practice of condom use among secondary school students in Kisumu District, Nyanza Province. Asian J Med Sci. 2011;3:32–6.

Teitelman AM, Bohinski JM, Tuttle AM. Condom coercion, sexual relationship power, and risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among young women attending urban family planning clinics. Fam Violence Prevent Health Pract. 2010;1(10):https://web.archive.org/web/20101031070908/http://endabuse.org/health/ejournal/2010/06/condom-coercion-sexual-relationship-power-and-risk-for-hiv-and-other-sexually-transmitted-infections-among-young-women-attending-urban-family-planning-clinics/.

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. “My partner was not fond of using condoms and I was not on contraception”: understanding adolescent mothers’ perspectives of sexual risk behaviour in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):366.

Maseko B, Hill LM, Phanga T, Bhushan N, Vansia D, Kamtsendero L, et al. Perceptions of and interest in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0226062.

Kawuma R, Ssemata AS, Bernays S, Seeley J. Women at high risk of HIV-infection in Kampala, Uganda, and their candidacy for PrEP. SSM Popul Health. 2021;13: 100746.

Elmes J, Nhongo K, Ward H, Hallett T, Nyamukapa C, White P, et al. The price of sex: condom use and the determinants of the price of sex among female sex workers in Eastern Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:S569–78.

AVERT. AIDS virus education research trust; sex workers, HIV and AIDS. 2019. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/key-affected-populations/sex-workers. Accessed October 2020

Mbonye M, Rutakumwa R, Weiss H, Seeley J. Alcohol consumption and high risk sexual behaviour among female sex workers in Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res. 2014;13(2):145–51.

Stankevitz K, Schwartz K, Hoke T, Li Y, Lanham M, Mahaka I, et al. Reaching at-risk women for PrEP delivery: What can we learn from clinical trials in sub-Saharan Africa? PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6): e0218556.

Wells BE, Kelly BC, Golub SA, Grov C, Parsons JT. Patterns of alcohol consumption and sexual behavior among young adults in nightclubs. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(1):39–45.

Mayanja Y, Kamacooko O, Bagiire D, Namale G, Seeley J. Epidemiological findings of alcohol misuse and dependence symptoms among adolescent girls and young women involved in high-risk sexual behavior in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176129.

Francis JM, Weiss HA, Mshana G, Baisley K, Grosskurth H, Kapiga SH. The epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders among young people in Northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10): e0140041-e.

Nash SD, Katamba A, Mafigiri DK, Mbulaiteye SM, Sethi AK. Sex-related alcohol expectancies and high-risk sexual behaviour among drinking adults in Kampala, Uganda. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(4):449–62.

Weiss HA, Vandepitte J, Bukenya JN, Mayanja Y, Nakubulwa S, Kamali A, et al. High levels of persistent problem drinking in women at high risk for HIV in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):153.

UNCST. National guidelines for research involving humans as research participants 2014. https://iuea.ac.ug/sitepad-data/uploads//2021/03/Human-Subjects-Protection-Guidelines-July-2014.pdf.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH064712 and the help they provided in drafting this manuscript. We also acknowledge the commitment of study staff and participants to the clinic activities and without whom we would not have archived the study outcomes.

Funding

This work was funded by IAVI and made possible by the support of many donors including United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The full list of IAVI donors is available at http://www.iavi.org. The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. IAVI also sponsored the study and therefore contributed to the study design, monitored the study and, reviewed and approved all versions of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JFL: Lead author and coordinated the data management, wrote the initial draft and revised versions of the manuscript, OK: contributed to study deign and carried out data analysis, VMK: contributed to study design, KC: contributed to study design, MK: contributed to study design, MP: contributed to study design, YM: contributed to study design, acquired funding, led the study team and mentored the first author through the manuscript writing process. All authors contributed to interpretation of study results and critically commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors attest they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee (GC/127/18/06/658) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS2435). A written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. We included emancipated and mature minors as defined in the national guidelines. They also gave written informed consent as per the national guidelines [55].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lunkuse, J.F., Kamacooko, O., Muturi-Kioi, V. et al. Low awareness of oral and injectable PrEP among high-risk adolescent girls and young women in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 22, 467 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07398-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07398-z