Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the main cause of cervical cancer. Characteristics of HPV infections, including the HPV genotype and duration of infection, determine a patient’s risk of high-grade lesions. Risk quantification of cervical lesions caused by different HPV genotypes is an important component of evaluation of cervical lesion. Data and evidence are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the pathogenicity of different HPV genotypes. The present study investigated the clinical characteristics of patients infected with single human papillomavirus (HPV) 53.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed the clinical data of patients who underwent cervical colposcopy guided biopsy between October 2015 and January 2021. The clinical outcomes and the follow-up results of the patients with single HPV53 infection were described.

Results

82.3% of the initial histological results of all 419 patients with single HPV53 infection showed negative (Neg). The number of patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)1, CIN2, CIN3, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN)1, CIN1 + VaIN1, CIN1 + VaIN2, and CIN2 + VaIN2 was 45, 10, 2, 9, 6, 1, and 1, respectively. Cancer was not detected in any patient. When the cytology was negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), we observed a significant difference in the distribution of histological results (P < 0.05). 95 patients underwent follow-up with cytology according to the exclusion criteria. No progression of high-grade lesions was observed during the follow-up period of 3–34 months.

Conclusions

The lesion caused by HPV53 infection progressed slowly. The pathogenicity of a single HPV53 infection was low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women, with an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths worldwide in 2020 [1]. The incidence and mortality rates of this malignancy have declined in most areas of the world over the past few decades; however, mortality rates for cervical cancers are considerably higher in developing vs. developed countries (12.4 vs. 5.2 per 100,000) [1]. The disease burden of cervical cancer is significantly high in China, the world’s most populous developing country. Statistical data show that in 2018, an estimated 106,430 new cases and 47,739 deaths in China were attributable to cervical cancer [2]. The incidence rate of cervical cancer has increased significantly, and the mortality rate is also on the rise [3].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the main cause of cervical cancer [4, 5]. Based on frequency of occurrence in cases of cervical cancer and available biological data, apha HPV types are classified as “carcinogenic to humans” (The International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC] classification Group 1), “probably/possibly carcinogenic to humans” (IARC Groups 2A and 2B), and “not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans” (IARC Group 3) [6]. The HPV53 genotype belongs to the IARC Group 2B and is relatively common in the population worldwide. So et al. [7] analyzed 1988 samples from healthy women, as well as those from women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1–3 and cervical cancer, and observed that HPV53 (9.3%) was the fourth most common HPV genotype among all samples in the study. Reportedly, HPV53 was one of the most frequent genotypes detected by several studies (prevalence rate 4.1–9.69%) [8,9,10]. Additionally, although HPV53 was considered to be a possible carcinogenic HPV type, it was detected in < 0.5% of invasive cervical cancer [11, 12]. Although many studies have focused on HPV infection, the clinical characteristics and risks of HPV53 infection remain inconclusive.

This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients who underwent cervical colposcopy guided biopsy. We investigated the clinical outcomes and follow-up results in patients with single HPV53 infection and recommend evidence-based clinical intervention strategies.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective case–control study was conducted in the Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China, and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (PRO2021-1292). We analyzed the clinical data of patients who underwent cervical colposcopy guided biopsy between October 2015 and January 2021. Among the 1048 patients with HPV53 infection, 424(40.5%) had single HPV53 infection and 624 (59.5%) had multiple HPV infection. Among the 424 patients, 419 patients without a history of cervical operation or hysterectomy were enrolled in the final statistical analysis (Fig. 1).

Following were the exclusion criteria: (1) surgical treatment administered, (2) pregnancy, (3) no follow-up within 1 year after biopsy, and (4) lost to follow-up. By January 2021, 95 of 419 patients underwent follow-up for 3–34 months after colposcopy guided biopsy. All patients underwent cytological evaluation (examination of cervicovaginal exfoliated cells) and HPV testing during follow-up. Some patients with new indications for colposcopy guided biopsy underwent new histological analysis. In addition to cervical examination, we performed careful colposcopy evaluation of the upper third of the vagina, including the fornices in all patients. Patients who underwent surgical treatment including excision and ablation therapy showed negative results on cytological evaluation performed at initial follow-up.

Standards and classification

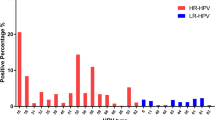

Patient age, the type of HPV infection, cytological and histological findings, and follow-up data were obtained from medical records. HPV genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction-based technology, including 13 high-risk HPV genotypes (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) and 2 possible high-risk HPV genotypes (HPV 53 and 66) [13]. Cytological findings were categorized as follows based on the 2001 Bethesda classification system: negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H), atypical glandular cells (AGC) (including subcategories of AGC), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and inadequate [14]. Histologic findings were interpreted based on the worst result obtained among all colposcopy guided biopsies, and these were categorized as follows: negative (Neg), CIN 1–3, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) 1–3.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous non-normally distributed variables are presented as median (range). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The (One-sample) Chi-square test were used whenever appropriate. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ median age was 45 (range 21–70) years. The number of patients with CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, VaIN1, CIN1 + VaIN1, CIN1 + VaIN2, and CIN2 + VaIN2 was 45, 10, 2, 9, 6, 1, and 1, respectively. Table 1 shows histological findings corresponding to the cytological results. Cancer was not detected in any patient in this study. When the cytology showed NILM, ASC-US and LSIL, we observed a significant difference in the distribution of histological results (P < 0.05).

Based on the aforementioned exclusion criteria, 95 patients underwent follow-up with cytology. 19 of the 95 patients underwent colposcopy guided biopsy. The median follow-up period was 12 (range 3–34) months. The initial cytological results showed NILM (n = 49), ASC-US (n = 22), LSIL (n = 23) and ASC-H (n = 1). Follow-up cytological results showed NILM (n = 83), ASC-US (n = 6), LSIL (n = 5) and AGC (n = 1). Initial histological findings showed 80 (84.2%) patients had Neg, 8 (8.4%) had were CIN1, 5 (5.3%) had VaIN1, and 2 (2.1%) had CIN1 + VaIN1 lesions. Follow-up histology showed results, 17 (89.5%) patients had Neg, 1 (5.3%) had CIN1, and 1 (5.3%) had VaIN1 lesions. During follow-up, 26 patients were infected with other high-risk HPV types (Table 2). No progression of high-grade lesions was observed during follow-up.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated 419 patients without a history of cervical surgery or hysterectomy, who presented with single HPV53 infection. The pathogenicity of single HPV53 infection was low; 82.3% of the initial histological results showed Neg and 14.3% showed CIN1, VaIN1, or CIN1 + VaIN1 lesions. No progression of high-grade lesions was observed during the follow-up period of 3–34 months; therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the lesions induced by single HPV53 infection progress slowly.

Characteristics of HPV infections, including the HPV genotype and duration of infection, determine a patient’s risk of high-grade lesions [15, 16]. Risk quantification of cervical lesions caused by different HPV genotypes is an important component of evaluation of cervical lesion [17]. Further data and evidence are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the pathogenicity of different HPV genotypes. Owing to regional cultural differences, a large number of resources and expenditure are allocated for HPV53 screening in some areas, and a few reports suggest that HPV53 infection is relatively common [7, 8, 10, 18], which may lead to panic among the population regarding this infection. Literature review yielded a few articles that describe HPV53 infection and follow-up [19, 20]; however, most studies included a small number of patients or did not perform comparison of histological results. Our study investigated the clinical outcomes of HPV53 infection and provides evidence to support for the association between HPV53 infection and cervical lesions. The long follow-up period of 34 months described the developmental trend of HPV53 infection, which will contribute to inform clinicians of appropriate treatment and follow-up strategies. Furthermore, unnecessary treatment can be avoided and patients’ anxiety can be reduced.

A large number of epidemiological studies have shown significant differences in HPV infection status and distribution across different countries or regions worldwide. Del et al. [9] found that in Italy, HPV42 was the most prevalent virus type, followed by HPV16, 53 and 31, with a lower prevalence of the HPV11, 82 and 35 genotypes. Kantathavorn et al. [21] observed that HPV52, 16, and 51 were the most common high-risk HPV genotypes detected in Thai women and HPV52 was common in Asians. HPV 16, 18, 35 and 45 were the most prevalent genotypes in northeastern Brazil [22]. In China, HPV types are also different owing to their geographical distribution [13, 23,24,25]. HPV53 infection has been reported in various places, and is relatively common [8,9,10, 18]. We investigated more than 1000 patients with HPV53 infection, who were treated at single center between October 2015 and January 2021, which indicates that HPV53 infection was relatively common in the population. Moreover, reportedly, a high percentage of single HPV infections are associated with cervical lesion (66.7–91.5%) [26]. Based on the methods used for HPV detection, the prevalence of multiple infections ranged from 1 to 52% [9, 27, 28]. Dickson et al. [29] observed that the HPV53 genotype was more likely to occur in multiple infections with other genotypes. Our study results are consistent with these findings. Among the 1048 patients with HPV53 infection who underwent initial investigation, in addition to 424 (40.5%) patients with single HPV53 infection, we observed a significantly large percentage of 624 (59.5%) patients with multiple HPV infections.

Many studies have reported that in contrast to the HPV16 variety, which is the most common HPV genotype that causes invasive cervical carcinoma (55.2%) and high-grade lesions (45.1%) [2], the HPV53 genotype is more commonly associated with low-grade lesions [7, 30]. Based on data provided by Padalko et al. [20], a sevenfold difference is observed in the frequency of ASC-US/LSIL (82.4%) and HSIL + (11.8%) in the cytological results of HPV53 infection. However, a meta-analysis showed that different distribution of HPV genotypes may be detected in HIV-positive women with HSIL, who were significantly more likely to be infected with the HPV53 genotype [31]. Our study showed that 405(96.7%) patients with single HPV53 infection had histological results of Neg, CIN1, VaIN1, or CIN1 + VaIN1, and only 14 (3.3%) patients showed CIN2, CIN3, CIN1 + VaIN2, or CIN2 + VaIN2. No patient showed cancer in our study, and no patient showed progression of high-grade lesions during follow-up. In our view, although the HPV53 genotype is designated as “possibly high risk” variety, the pathogenicity of single HPV53 infection was not so serious, and it is not a rapidly progressive infection.

The main limitation of the study is its retrospective nature. Although all data were obtained from medical records, due to the quality of cytological specimens and the variety of HPV genotyping methods, samples and test results were obtained from multiple centers, and discrepancies in findings across various centers may have affected our results. Currently, no reference standard is available for HPV genotyping, and further research is warranted in this field. Notably, in this study, the cytological findings were classified based on the 2001 Bethesda classification system, and histological results of colposcopy guided biopsy were obtained from a single center. Therefore, in our opinion, our conclusions are reliable. As mentioned earlier, this was a single-center study, and multicenter studies are warranted to exclude possible biases associated with single-center research.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that single HPV53 infection shows low pathogenicity and is not a rapidly progressive condition. Combined with the results of cytological screening, some patients with single HPV53 infection might appropriately extend the screening interval. Our findings contribute to inform clinicians of appropriate treatment and follow-up strategies for patients with single HPV53 infection.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper. Requests for additional information should be addressed to the corresponding author and data may be provided on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AGC:

-

Atypical glandular cells

- ASC-H:

-

Atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- ASC-US:

-

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- CIN:

-

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- HSIL:

-

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- LSIL:

-

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- Neg:

-

Negative

- NILM:

-

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- VaIN:

-

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, et al. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human papillomavirus and related diseases in China. Summary report 17 June 2019. Accessed 17 Mar 2021.

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21338.

zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in human cancers. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111(6):581–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.99723.x.

Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):518–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021641.

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens—part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):321–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8.

So KA, Lee IH, Lee KH, Hong SR, Kim YJ, Seo HH, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype-specific risk in cervical carcinogenesis. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30(4): e52. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e52.

Tsao KC, Huang CG, Kuo YB, Chang TC, Sun CF, Chang CA, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes in northern Taiwanese women. J Med Virol. 2010;82(10):1739–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21870.

Del Prete R, Ronga L, Magrone R, Addati G, Abbasciano A, Di Carlo D, et al. Epidemiological evaluation of human papillomavirus genotypes and their associations in multiple infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147: e132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818003539.

Ouh YT, Min KJ, Cho HW, Ki M, Oh JK, Shin SY, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes and precancerous cervical lesions in a screening population in the Republic of Korea, 2014–2016. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(1): e14. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e14.

de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, Geraets DT, Klaustermeier JE, Lloveras B, et al. Retrospective International Survey and HPV Time Trends Study Group. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1048–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8.

Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R, Snijders PJ, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(4):927–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25396.

Li J, Gao JJ, Li N, Wang YW. Distribution of human papillomavirus genotypes in western China and their association with cervical cancer and precancerous lesions. Arch Virol. 2021;166(3):853–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-021-04960-z.

Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. Bethesda 2001 Workshop. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2114–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.16.2114.

Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn ST, Zuna RE, Walker J, Allen RA, et al. Grading the severity of cervical neoplasia based on combined histopathology, cytopathology, and HPV genotype distribution among 1,700 women referred to colposcopy in Oklahoma. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(4):964–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23969.

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-264.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.042.

Sundström K, Eloranta S, Sparén P, Arnheim Dahlström L, Gunnell A, Lindgren A, et al. Prospective study of human papillomavirus (HPV) types, HPV persistence, and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2010;19(10):2469–78. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0424.

Sohrabi A, Hajia M, Jamali F, Kharazi F. Is incidence of multiple HPV genotypes rising in genital infections? J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(6):730–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.10.006.

Meyer T, Arndt R, Beckmann ER, Padberg B, Christophers E, Stockfleth E. Distribution of HPV 53, HPV 73 and CP8304 in genital epithelial lesions with different grades of dysplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11(3):198–204. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01009.x.

Padalko E, Ali-Risasi C, Van Renterghem L, Bamelis M, De Mey A, Sturtewagen Y, et al. Evaluation of the clinical significance of human papillomavirus (HPV) 53. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;191:7–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.04.004.

Kantathavorn N, Mahidol C, Sritana N, Sricharunrat T, Phoolcharoen N, Auewarakul C, et al. Genotypic distribution of human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cytology findings in 5906 Thai women undergoing cervical cancer screening programs. Infect Agent Cancer. 2015;10:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-015-0001-5.

da Silva RL, da Silva BZ, Bastos GR, Cunha APA, Figueiredo FV, de Castro LO, et al. Role of HPV 16 variants among cervical carcinoma samples from Northeastern Brazil. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01035-0.

Ding X, Liu Z, Su J, Yan D, Sun W, Zeng Z. Human papillomavirus type-specific prevalence in women referred for colposcopic examination in Beijing. J Med Virol. 2014;86(11):1937–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24044.

Zhao XL, Hu SY, Zhang Q, Dong L, Feng RM, Han R, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus genotype distribution and attribution to cervical cancer and precancerous lesions in a rural Chinese population. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(4): e30. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e30.

Wu XL, Zhang CT, Zhu XK, Wang YC. Detection of HPV types and neutralizing antibodies in women with genital warts in Tianjin City, China. Virol Sin. 2010;25(1):8–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-010-3078-4.

Quek SC, Lim BK, Domingo E, Soon R, Park JS, Vu TN, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia across 5 countries in Asia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(1):148–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31827670fd.

Panotopoulou E, Tserkezoglou A, Kouvousi M, Tsiaousi I, Chatzieleftheriou G, Daskalopoulou D, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, and 33 in a cohort of Greek women. J Med Virol. 2007;79(12):1898–905. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21025.

Trottier H, Mahmud S, Costa MC, Sobrinho JP, Duarte-Franco E, Rohan TE, et al. Human papillomavirus infections with multiple types and risk of cervical neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(7):1274–80. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-06-0129.

Dickson EL, Vogel RI, Bliss RL, Downs LS Jr. Multiple-type human papillomavirus (HPV) infections: a cross-sectional analysis of the prevalence of specific types in 309,000 women referred for HPV testing at the time of cervical cytology. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(7):1295–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829e9fb4.

Argyri E, Papaspyridakos S, Tsimplaki E, Michala L, Myriokefalitaki E, Papassideri I, et al. A cross sectional study of HPV type prevalence according to age and cytology. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-53.

Clifford GM, Gonçalves MA, Franceschi S, HPV and HIV Study Group. Human papillomavirus types among women infected with HIV: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2006;20(18):2337–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000253361.63578.14

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the Key research projects of traditional Chinese medicine in Zhejiang Province (No.2020ZZ014). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

No specific funding or support was obtained for the purpose of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RZC: study conception and design, data collection and analysis, manuscript writing. YFF: study conception and design, supervision, manuscript editing. BBY: intellectual content, data collection and analysis. YL: data collection and analysis. YLY: data collection and analysis. XYW: manuscript editing. XDC: study conception and design, supervision, manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (PRO2021-1292). This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Furthermore, the consent of the study participants was deemed unnecessary as the study only concerned the retrospective review of the medical database. The need of informed consent was waived by the ethics committee {Medical Ethics Committee of the Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine} for this retrospective study. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, R., Fu, Y., You, B. et al. Clinical characteristics of single human papillomavirus 53 infection: a retrospective study of 419 cases. BMC Infect Dis 21, 1158 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06853-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06853-7