Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in Thai women. Nevertheless, the preventive strategy such as HPV vaccination program has not been implemented at the national level. This study explored the HPV prevalence and genotypic distribution in a large cohort of Thai women.

Methods

A hospital-based cervical cancer screening program at Chulabhorn Hospital, Bangkok and a population-based screening program at a rural Pathum Thani Province were conducted using liquid-based cytology and HPV genotyping.

Results

Of 5906 women aged 20–70 years, Pap smear was abnormal in 4.9% and the overall HPV prevalence was 15.1%, with 6.4% high-risk (HR), 3.5% probable high-risk (PR), and 8.4% low-risk (LR) HPV. The prevalence and genotypic distribution were not significantly different between the two cohorts. Among HR-HPV genotypes, HPV52 was the most frequent (1.6%), followed by HPV16 (1.4%), HPV51 (0.9%), HPV58 (0.8%), HPV18 (0.6%), and HPV39 (0.6%). Among LR-HPV genotypes, HPV72 and HPV62 were the most frequent while HPV6 and HPV11 were rare. HPV infection was found to be proportionately high in young women, aged 20–30 years (25%) and decreasing with age (11% in women aged >50). The more severe abnormal cytology results, the higher positivity of HR-HPV infection was observed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, HPV52, HPV16, and HPV51 were identified as the most common HR-HPV genotypes in Thai women. This study contributes genotypic evidence that should be essential for the development of appropriate HPV vaccination program as part of Thailand’s cervical cancer prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cervical cancer is the third most common female cancer worldwide after breast cancer and colon cancer with age standardized incidence rate (ASR) of 14.0/100000 person-year [1]. Thailand is an endemic area of cervical cancer with ASR of 17.8/100000 person-year [1]. Infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is a causal and necessary factor for the development of cervical cancer, with its prevalence in cervical cancers of 99.7% [2-6]. As a primary cervical cancer prevention, HPV vaccine has been developed to protect against HPV16 and 18 infections which are commonly found in general population and cervical cancer cases globally [7-11].

Since HPV genotypic distribution can be area-specific, it is necessary to determine its genotypic distribution before establishing health care policies and vaccination programs in each area [8,9]. This study was conducted to assess the prevalence and characteristics of HPV genotypes in Thai women as the cervical cancer prevalence has been the highest in the past many decades. Two steps were executed; Step 1 - a large hospital-based study at Chulabhorn Hospital, Bangkok followed by Step 2 - a population-based study at Bangkhayaeng District, Pathum Thani Province. The ultimate goal was to provide scientific evidence essential for the design and implementation of Thailand’s cervical cancer prevention policies.

Materials and methods

Study population and enrollment

After approval by the Ethical Committee for Human Research of Chulabhorn Hospital, the first hospital-based study was performed among 4550 Thai females, aged 20–70 years, who were voluntarily registered into the screening program at Chulabhorn Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand during July 19, 2011 - November 5, 2012. Exclusion criteria included absence of cervix, previous HPV vaccine vaccination, history of abnormal cytology or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or cervical carcinoma, prior HPV infection, active disease for any types of cancer during the last 5 years, or unable to receive follow-ups throughout the program. Sixty-three women were excluded. All participants received detailed information regarding the study objectives and consented to the study. Demographics, obstetric and gynecologic history, and cervical cancer screening data were collected. The population-based study was subsequently undertaken in the Bangkhayaeng District, Pathum Thani Province using permanent living (named in the census registration) or current living status in Bangkhayaeng area at the day of pelvic examination to recruit a total of 1668 Thai females, aged 20–70 years who then underwent cervical cancer screening during February 4-June 16, 2013. Exclusion criteria were the same as our previous study.

Sample collection and preparation

Samples were obtained using a cytobrush by gynecologic oncologists or well-trained general practitioners for pelvic examination of Chulabhorn Hospital. The brush was then placed in the preservative fluid in the BD SurePath Pap test kit (BD Diagnostics-Tripath, Burlington, NC, USA) for both liquid-based cytology and HPV DNA testing. The investigators performing HPV typing were blinded to cytology results. All cervical cytology slides were interpreted per normal routine by qualified pathologists at Chulabhorn Hospital, using the Bethesda 2001 report system [12].

HPV genotyping

For the identification of HPV genotypes, we used the Linear array HPV testing (Roche, USA). This kit was capable of identifying 37 HPV types including 12 high-risk (HR), 8 probable high-risk (PR), and 17 low-risk (LR) types those classified by oncogenic potentiality [13-16]. In brief, 450-bp fragments from the L1 region of the virus were first amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of target DNA, followed by hybridization using a reverse line blot system for simultaneous detection of up to 37 HPV genotypes (i.e., genotypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 81, 82, 83, 84, IS39, and CP6108).

PCR amplification

Each 100 μL reaction consisted of 50 μL working master mix and 50 μL of DNA sample. Amplification was performed in an Applied Biosystems GeneAmp PCR System 9700 using the recommended parameters: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 9 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min and 72°C for 5 min before holding indefinitely at 72°C.

Hybridization to the oligonucleotide probe

Following PCR amplification, the HPV and the ß-globin amplicon were chemically denatured to form single stranded DNA by addition of 100 μL Denaturation Solution. Aliquots 100 μL of denatured amplicon were then transferred to the appropriate well of typing tray containing hybridization buffer and single LINEAR ARRAY HPV Genotyping Strip coated with HPV and ß-globin probe lines. The biotin-labeled amplicon was hybridized to the oligonucleotide probes only if the amplicon contained the matching sequence of complementary probe.

Colorimetric determination

A blue colored complex precipitated at the probe positions where hybridization occurred. Then, the linear array HPV genotyping strip was read visually by comparing the pattern of blue lines to the linear array HPV genotyping test reference guide.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the distribution types and frequencies of HPV positivity, age, and cytology results. Frequency tables were done for qualitative variables. Independent samples t-test was used compare the means of age and Pearson’s chi-square test were performed to verify the association of demographic data and HPV prevalence between the two cohorts. p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Licensed Stata program version 12 was used for analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics of 5906 Thai women

Demographic characteristics of 2 cervical cancer screening populations were shown in Table 1. Of 5906 women, the median age was 45 years with a range of 20–70 years. Approximately two-thirds of them were pre-menopausal and had prior pregnancy history. The proportion of those having children and being married was higher in the Bangkhayaeng cohort than Chulabhorn Hospital cohort. Women in the Bangkhayaeng District were of lower educational level as compared to the Chulabhorn Hospital cohort.

HPV prevalence and genotypic distribution

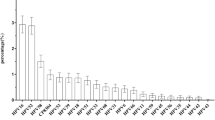

Table 2 demonstrates the overall HPV prevalence among 5906 Thai women was 15.1%, with 6.4% high risk (HR), 3.5% probable high risk (PR), and 8.4% low risk (LR) HPV. No significant difference was identified on the HPV prevalence between the two cohorts (p = 0.178). Overall, the most frequent HR-HPV types consisted of HPV52 (1.6%), HPV16 (1.4%), HPV51 (0.9%), HPV58 (0.8%), HPV18 (0.6%), and HPV39 (0.6%). Common PR-HPV types were HPV70 (1.0%), HPV66 (0.8%), HPV53 (0.8%), and HPV68 (0.6%). LR-HPV subtypes were HPV72 (2.5%), HPV62 (1.7%), HPV84 (1.1%), HPV71 (1.0%), and HPV61 (0.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 2 shows the distribution of HR-HPV prevalence in each cohort. The most common HR-HPV in Chulabhorn Hospital Cohort was HPV52, 16, 51, 58, 39 and 18 (26%, 21.2%, 12.7%, 12.7%, 10.6%, and 9.2%, respectively). The most common HR-HPV in Bangkhayaeng District Cohort was HPV16, 51, 52, 58, 18 and 59 (21.4%, 21.4%, 21.4%, 12.7%, 9.5%, and 6.2%, respectively).

Age-specific prevalence of HPV infection and abnormal Pap smear

Pap smear was abnormal in 4.9% of the population. The abnormal Pap smear rate was highest in those young women aged 20–30 years (6.6%) and decreased by advancing age (Table 3). In addition, HPV infection was found most frequent among women aged < 30 years, with the prevalence of 24.8% (13.2% of HR-HPV), and decreased by increasing age.

HPV infection frequency and abnormal cervical cytology

The HPV positivity rates in cases with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) (n = 189, 3.2%), atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H) (n = 11, 0.2%), low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (n = 66, 1.1%), and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) (n = 20, 0.3%) was 31.2%, 45.5%, 86.4% and 90.0%, respectively. The more severe cytological result, the higher HPV-positive proportion was found.HPV, HR-HPV positive samples with normal cytology in 5614 women amounted to 13.3%, 5.1%, respectively. The most common HR-HPV type was HPV52 (1.4%), HPV16 (0.9%), HPV51 (0.6%), HPV58 (0.6%), HPV18 (0.5%), and HPV39 (0.5%), respectively. The overall HPV prevalence in 292 women with abnormal cytology was 48.6% (HR-HPV 31.2%).The most common HR-HPV types in this group included HPV16 (9.6%), HPV51 (6.9%), HPV52 (5.8%), HPV58 (3.8%), HPV59 (3.4%), and HPV18 (2.4%) as shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

We investigated the prevalence and distribution of HPV genotypes among 5906 Thai women enrolled for cervical cancer screening at Chulabhorn Hospital, Bangkok, or Bangkhayaeng District, Pathum Thani and revealed the 15% HPV infection rate among these women. The overall prevalence in both hospital-based and population-based cohorts was not statistically different despite the significant differences in the cohorts’ demographic characteristics as shown in Table 1. The rural Bangkhayaeng District appeared to comprise more uneducated, multiparous, and married women than the Chulabhorn Hospital-based cohort in Bangkok. The genotypic data was not different between the two cohorts suggesting that the rate and type of HPV infections in Thai women in this study were comparable regardless of their geographic locations and education levels. However, larger studies involving more sub-regions of Thailand may be needed.

Major studies from the Western countries reported the prevalence of HR-HPV infections around 11.3%-18.3% which were higher than our results [17-21]. Disparate data from three previous studies conducted in Thailand currently exist showed the lower prevalence of HPV infections (6.3%-8.7%) which could be attributed to different genotypic methods utilized in each study [22-24]. A study by the National Cancer Institute of Thailand reported the overall prevalence of 13 HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) of 8.2% by Hybrid Capture 2 hybridization assay method without specific genotypic data [22]. Another Thai study utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for E1 amplification for 20 HPV genotypes (HR type 16, 18, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82, PR type 66, and LR type 6, 11) found the HPV prevalence of 8.7% among 1662 women in the screening setting [23]. The higher HPV prevalence in our cohort that differs from other Thai cohorts may reflect our more comprehensive genotypic analysis that was aimed to detect more HPV genotypes (37 genotypes) than other Thai studies, regardless of cervical cancer risk categories. Nevertheless, the HR-HPV prevalence in this study of 6.4% was comparable to most previously reported Thai studies [22-24].

With respect to the HR-HPV genotypes that are the major risk factors for cervical cancer, it was of interest to find that in our Chulabhorn Hospital Cohort, the most common genotype was HPV52 followed by HPV16 and HPV51. This finding was in contrast to most studies in the Western countries and two smaller studies in Thailand in which HPV16 was identified as the most frequent [23,24]. Nevertheless, HPV16 and HPV51 were also well represented together with HPV52 as the top HR-HPV genotypes in our Bangkhayaeng District Cohort. When classified by continents, it was observed that HPV16 was the first top-ranking HPV genotype as shown in Table 4, whereas the second and other subsequent rankings were distinctively changed according to each region [9]. For instance, HPV52 and HPV31 were the second top-rankings in Africa and Europe, respectively. Meanwhile, in the Asia continent, the most commonly found HPV included HPV16, HPV18, and HPV52, with the prevalence of 2.5%, 1.4% and 0.7%, respectively [25-32]. Parkin et al. studied the HPV prevalence in a normal cytology group of 28998 Eastern Asian female cases and revealed that the most common HR-HPV types were HPV16, HPV52, HPV58, HPV18, HPV56, and HPV51, with the prevalence of 2.7%, 1.3%, 1.2%, 0.7%, 0.7%, 0.7%, respectively [27]. A study in China also showed a high frequency of HPV16, HPV52, HPV58, and HPV18 [26]. Bruni et al. performed meta-analysis on HPV prevalence in one million normal cytology woman which showed HR-HPV infection rate of 11.7% and the five most common HR-HPV types worldwide were HPV16 (3.2%), HPV18 (1.4%), HPV52 (0.9%), HPV31 (0.8%), and HPV58 (0.7%) [9]. Recently, Zhao et al. reported that the most commonly HR-HPV in cervical specimens at baseline from Chinese women aged 18–25 years were HPV-52 (4.0%) and HPV-16 (3.7%) [33]. Interestingly, HPV18, the most frequently detected HR-HPV after HPV16 worldwide, was surprisingly uncommon in our study population. Our data is consistent with results from previous Thai studies that reported a very low prevalence of HPV18 [23,24].

When considering the significance of HPV52 in Thai women compared to worldwide invasive cancer cases in the meta-analysis of 30848 cases from 243 studies, the prevalence of global HR-HPV was 89.9%, with HPV16 and HPV18 as the most common types, followed by HPV types 58, 33, 45, 31, 52, 35, 59, 36 and 51, respectively [11]. In our study of 292 women with abnormal cytology, about half of them had HPV infections and the most common HR-HPV types continued to be the common HR-HPV types found in the normal cytology cases, including HPV16, HPV51, HPV52 followed by HPV58, HPV59, and HPV18, respectively. HPV52 was also frequently identified in two small cervical cancer studies reported from Thailand [34,35]. A study by Thai NCI in 155 cases of cervical cancer showed that the most commonly identified types were HPV16, HPV18, HPV52, HPV58, and HPV33 [35]. Similar results from a study by Chiang Mai University Hospital in the Northern Thailand in 99 cases of cervical cancer showed that the most frequently found HR-HPV consisted of HPV16, HPV52, HPV18, HPV33, and HPV58 [34]. HPV52 thus plays an important role in the Thai population.

HPV prevalence is strongly associated with age worldwide [8,9]. We noted a decline in the HPV prevalence, both HR-HPV and non-HR-HPV genotypes, with increasing age of the women in this study. It is also of interest to find a lower rate of HPV infection (24.8%) and HR-HPV genotypes (13.2%) in our young population aged <30 years as compared to worldwide or Western continent data, which showed a higher HR-HPV prevalence of 20-30% in women aged <30 years [8,9]. A follow-up study of these young women is presently ongoing to determine the natural history of HPV infections in this particular subgroup. Moreover, 13.3% of women in our study had HPV infection despite negative cytology results. This data was comparable to a meta-analysis performed by de Sanjose et al. which showed HR-HPV prevalence of 10.4% in women with negative cytology results [8]. These women infected with HPV despite negative cytology results are also being followed to assess the persistence of HPV and CIN development.

Future cervical cancer screening is moving towards HPV-based screening because of its very high sensitivity [36-38]. A randomized control study by Mayrand et al. in 10154 women showed that HPV testing alone had a higher sensitivity (94.6%) for detection of CIN2+ when compared to conventional Pap smears (55.4%) [36]. In a country with a low prevalence of HR-HPV as Thailand, primary HR-HPV testing would have a high yield because the positive rate is not too high and will not lead to overwhelming referral for secondary triage or even colposcopy. Pap smear of unnecessary cases could be possibly reduced by 93.6%.

In conclusion, this study represents the largest report from Thailand with respect to detailed and comprehensive genotypic analysis of HPV subtypes. The prevalence and genotypic distribution of HPV did not significantly differ between hospital-based and population-based cohorts. HPV52 was the most frequently identified high-risk genotype in Thai women followed by HPV16 and HPV51. The majority of Thai women undergoing cervical cancer screening programs were not infected by readily available vaccine-preventable HPV genotypes (HPV16, HPV18, HPV6, and HPV11). This study thus provides scientific evidence essential for the development of appropriate HPV vaccination programs targeted for certain HR-HPV genotypes prevalent in the Thai women.

Abbreviations

- ASC-H:

-

Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- ASC-US:

-

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- ASR:

-

Age standardized incidence rate

- CIN:

-

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- HR:

-

High risk

- HSIL:

-

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- LR:

-

Low risk

- LSIL:

-

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- NCI:

-

National Cancer Institute

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PR:

-

Probable high risk

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No.11 [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France; 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on 18/11/2014.

Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:244–65.

Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Chapter 1: human papillomavirus and cervical cancer–burden and assessment of causality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:3–13.

Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9.

Chin'ombe N, Sebata NL, Ruhanya V, Matarira HT. Human papillomavirus genotypes in cervical cancer and vaccination challenges in Zimbabwe. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9:16.

Ermel A, Ramogola-Masire D, Zetola N, Tong Y, Qadadri B, Azar MM, et al. Invasive cervical cancers from women living in the United States or Botswana: differences in human papillomavirus type distribution. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9:22.

Franco EL, Harper DM. Vaccination against human papillomavirus infection: a new paradigm in cervical cancer control. Vaccine. 2005;23:2388–94.

de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Munoz N, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:453–9.

Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1789–99.

Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890–907.

Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R, Snijders PJ, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: Variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:927–35.

Apgar BS, Zoschnick L, Wright Jr TC. The Bethesda system terminology. Am Fam Physician. 2001;2003(68):1992–8.

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518-527.

Cogliano V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. Carcinogenicity of human papillomaviruses. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:204.

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. WHO international agency for research on cancer monograph working group: a review of human carcinogens–part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2.

Schiffman M, Clifford G, Buonaguro FM. Classification of weakly carcinogenic human papillomavirus types: addressing the limits of epidemiology at the borderline. Infect Agent Cancer. 2009;4:8.

Ralston Howe E, Li Z, McGlennen RC, Hellerstedt WL, Downs LS Jr. Type-specific prevalence and persistence of human papillomavirus in women in the United States who are referred for typing as a component of cervical cancer screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:245 e1-7.

Dickson EL, Vogel RI, Bliss RL, Downs Jr LS. Multiple-type human papillomavirus (HPV) infections: a cross-sectional analysis of the prevalence of specific types in 309,000 women referred for HPV testing at the time of cervical cytology. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1295–302.

Agarossi A, Ferrazzi E, Parazzini F, Perno CF, Ghisoni L. Prevalence and type distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in women undergoing voluntary cervical cancer screening in Italy. J Med Virol. 2009;81:529–35.

Anderson L, O'Rorke M, Jamison J, Wilson R, Gavin A, HPV Working Group members. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in women attending cervical screening in the UK and Ireland: new data from northern Ireland and a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2013;85:295–308.

Ucakar V, Poljak M, Klavs I. Pre-vaccination prevalence and distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types in Slovenian women: a cervical cancer screening based study. Vaccine. 2012;30:116–20.

Swangvaree SS, Kongkaew P, Rugsuj P, Saruk O. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection and cytologic results in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1465–8.

Chansaenroj J, Lurchachaiwong W, Termrungruanglert W, Tresukosol D, Niruthisard S, Trivijitsilp P, et al. Prevalence and genotypes of human papillomavirus among Thai women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:117–22.

Sukvirach S, Smith JS, Tunsakul S, Munoz N, Kesararat V, Opasatian O, et al. Population-based human papillomavirus prevalence in Lampang and Songkla, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1246–56.

Inoue M, Sakaguchi J, Sasagawa T, Tango M. The evaluation of human papillomavirus DNA testing in primary screening for cervical lesions in a large Japanese population. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1007–13.

Li H, Zhang J, Chen Z, Zhou B, Tan Y. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes among women in Hunan province, China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:202–5.

Parkin DM, Louie KS, Clifford G. Burden and trends of type-specific human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in the Asia Pacific region. Vaccine. 2008;26 Suppl 12:M1–16.

Maehama T. Epidemiological study in Okinawa, Japan, of human papillomavirus infection of the uterine cervix. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2005;13:77–80.

Sriamporn S, Snijders PJ, Pientong C, Pisani P, Ekalaksananan T, Meijer CJ, et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer from a prospective study in Khon Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:266–9.

Aggarwal R, Gupta S, Nijhawan R, Suri V, Kaur A, Bhasin V, et al. Prevalence of high–risk human papillomavirus infections in women with benign cervical cytology: a hospital based study from North India. Indian J Cancer. 2006;43:110–6.

Arora R, Kumar A, Prusty BK, Kailash U, Batra S, Das BC. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) types 16 and 18 in healthy women with cytologically negative Pap smear. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121:104–9.

Dai M, Bao YP, Li N, Clifford GM, Vaccarella S, Snijders PJ, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in Shanxi Province, People’s Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:96–101.

Zhao FH, Zhu FC, Chen W, Li J, Hu YM, Hong Y, et al. Baseline prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in healthy Chinese women aged 18–25 years enrolled in a clinical trial. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2604–11.

Siriaunkgul S, Suwiwat S, Settakorn J, Khunamornpong S, Tungsinmunkong K, Boonthum A, et al. HPV genotyping in cervical cancer in Northern Thailand: adapting the linear array HPV assay for use on paraffin-embedded tissue. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:555–60.

Chinchai T, Chansaenroj J, Swangvaree S, Junyangdikul P, Poovorawan Y. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes in cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1063–8.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, Walter SD, Hanley J, Ferenczy A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–88.

Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1385–94.

Leinonen M, Nieminen P, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, Malila N, Tarkkanen J, Laurila P, et al. Age-specific evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening vs conventional cytology in a randomized setting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1612–23.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the Royal Project graciously granted by Professor Dr. HRH Princess Chulabhorn Mahidol to help the people of Thailand as routine HPV screening is not covered under Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage Program. We appreciated all individuals, particularly the Cervical Cancer Care Team and Data Management Unit who generously spared their time for the accomplishment and fulfillment of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NK carried out the literature review, study design, patient recruitment, data collection, statistical analysis, manuscript drafting and revision. CM was responsible for the initiation, support, and execution of the entire project. NP, CT and SS were responsible for data collection and patient coordination. CA helped with study design, data analysis, and critical revisions of the manuscript. TS and NT carried out cytopathology interpretation. NS and WU carried out HPV genotyping analysis. GS was responsible for sample preparation and laboratory processing. WK carried out statistical analysis and AA helped with project coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kantathavorn, N., Mahidol, C., Sritana, N. et al. Genotypic distribution of human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cytology findings in 5906 Thai women undergoing cervical cancer screening programs. Infect Agents Cancer 10, 7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-015-0001-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-015-0001-5