Abstract

Background

PCRs targeting 16S ribosomal DNA (16S PCR) followed by Sanger’s sequencing can identify bacteria from normally sterile sites and complement standard analyzes, but they are expensive. We conducted a retrospective study in the Strasbourg University Hospital to assess the clinical impact of 16S PCR sequencing on patients’ treatments according to different sample types.

Methods

From 2014 to 2018, 806 16S PCR samples were processed, and 191 of those were positive.

Results

Overall, the test impacted the treatment of 62 of the 191 patients (32%). The antibiotic treatment was rationalized in 31 patients (50%) and extended in 24 patients (39%), and an invasive procedure was chosen for 7 patients (11%) due to the 16S PCR sequencing results. Positive 16S PCR sequencing results on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) had a greater impact on patients’ management than positive ones on cardiac valves (p = 0.044). The clinical impact of positive 16S PCR sequencing results were significantly higher when blood cultures were negative (p < 0.001), and this difference appeared larger when both blood and sample cultures were negative (p < 0.001). The diagnostic contribution of 16S PCR was higher in patients with previous antibiotic treatment (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In all, 16S PCR analysis has a significant clinical impact on patient management, particularly for suspected CSF infections, for patients with culture-negative samples and for those with previous antibiotic treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial infections in hospitalized patients can lead to sepsis and death [1], particularly when the diagnosis is delayed [2]. Prompt appropriate antimicrobial therapy can improve patients’ outcomes.

Gram stain results of biological samples can offer a first guidance, but usually, clinicians have to wait for standard culture results for final bacterial species identification with the help of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and for secondary antimicrobial susceptibility testing. However, standard cultures have limitations regarding fastidious or even non-cultivable bacteria [3], and false negative results can be obtained following antibiotic treatments [4]. Empirical antibiotic therapies present various pitfalls: broad spectrum or prolonged antibiotic treatments increase the risks of drug toxicity [5], of Clostridioides difficile infections [6], of opportunistic fungal infections [7] and of multidrug-resistant bacteria selection [8]. Also, erroneous antibiotic therapies due to the lack of bacterial identification preclude patient recovery. Thus, other rapid molecular tests have emerged to improve microbiological diagnoses.

16S rDNA PCR sequencing, a commonly used broad range PCR analysis, has demonstrated its diagnostic performance on various samples: cardiac valves [9,10,11], abscesses [12], cerebrospinal fluids (CSFs) [13], bone and joint samples [14], sonication fluids [15], pleural fluids [16] and eye samples [17]. Different primers targeting conserved regions of 16S ribosomal DNAs are used to amplify nucleic acids via PCR, followed by sequencing. Variable regions of this gene allow identification to the species level, especially using phylogenetic tree reconstructions [18]. This method has multiple advantages including large implementation in the routine workflow of clinical laboratories and the possibility to detect non-cultivable bacteria or not viable bacteria following antibiotic therapy [3], but it is also expensive.

The clinical impact of this method on the patients’ treatments in real clinical settings has been rarely studied. Our main objective was to assess the impact of positive 16S rDNA PCR analyzes (in various samples) on clinical outcome of patients. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the bacterial identification performance and the effect of a previous antibiotic therapy on the results and to analyze the management of discordant results between 16S PCR and culture identification.

Methods

Study design and ethical considerations

This was a single center retrospective study. We included data from all patients with positive 16S PCR results in the Strasbourg University Hospital laboratory from 2014 to 2018. According to the French legislation (Jardé law, N°2016–800), we sought for the non-opposition of all patients. The Strasbourg Hospital Ethic Committee approved this study (reference FC/dossier 2019–27).

Data collection

We collected all positive 16S PCR results from the microbiological laboratory information system and recovered clinical and laboratory data from the electronic medical records of the relevant patients. We removed all duplicated results and kept a single result per patient. We collected data on the results of blood cultures, the samples’ Gram stains and cultures, the bacteria identified, the presence of previous antibiotic treatments, the clinical impact of the 16S PCR results and the final diagnoses.

We defined the notion of clinical impact of the 16S PCR as a rationalizing of the antibiotic therapy (‘R’, lower dose, shorter or more targeted antibiotic therapy), an extended antibiotic therapy (‘E’, higher dose, longer or extended spectrum antibiotic therapy) or an intervention (‘I’, invasive procedures). Modifications of the patient’s management had to be directly associated with the 16S PCR results based on medical records. We considered previous antibiotic treatments as significant when given for more than 24 h before the sample collection and when being effective against the identified pathogen.

Sample analyzes

We analyzed blood cultures using the BD BACTEC™ FX instrument (Becton Dickinson). Cardiac valves, bone samples and abscesses were ground in brain heart infusion broth. We used a published sonication protocol [19]. Samples were cultivated using standard media after Gram-stained standard identifications. According to the sample type, the cultures were incubated under both aerobic (35 °C for Columbia agar + 5% sheep blood and Drigalski, 35 °C in 5% CO2 for chocolate agar) and anaerobic conditions (Schaedler agar + 5% sheep blood and thioglycolate broth). Joint fluids, bone samples and sonication fluids were also incubated in BD BACTEC™ Peds Plus™ vials, as described [20]. Bacteria were usually identified with MALDI-TOF MS [21] using the Microflex LT coupled to the MALDI Biotyper algorithm (Bruker) as described [22].

16S rDNA PCR protocol

16S rDNA PCRs were performed once a week at the request of clinicians or by microbiologists’ initiative and systematically on cardiac valve samples with suspected endocarditis when the sample’s cultures were negative. Briefly, purified DNA was extracted from clinical samples using MagNA Pure (Roche), PCRs were performed with the LightCycler® 2.0 (Roche) instrument with 27F/16S1RRB primers and sequencing reactions were performed using the Sanger method on an ABI 3730 XL system (Applied Biosystems) as described in detail [23]. A microbiologist analyzed the results using the online tool leBIBIQBPP [24] (https://umr5558-bibiserv.univ-lyon1.fr/lebibi/lebibi.cgi) to compare the tested sequence to sequences derived from the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (http://www.insdc.org) – including the GenBank® database and EMBL-ENI –, allowing construction of phylogenetic unrooted approximate maximum-likelihood trees and bacterial final identification by using the minimal patristic distance and the nearest reference strain in the tree as the decision criteria. Conclusions were transmitted to the clinicians.

Statistical analysis

We presented categorical variables as numbers and percentages and performed comparisons between groups using Fisher’s exact tests. In case of significant differences between multiple groups, we carried out pairwise post hoc tests. Adjusted p-values were calculated using the ‘Holm’ method to account for multiple comparisons. We considered p-values < 0.05 as statistically significant. We performed all statistical analyses using the R software version 3.5.1 R core team 2018 (Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

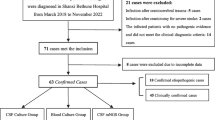

From 2014 to 2018, 835 16S rDNA PCRs were performed in our laboratory, and 197 (24%) were positive with a final bacterial identification. Among these 835 results, we excluded 23 because we could not determine their type of sample precisely and 6 due to incomplete clinical records. In the end, we analyzed data from 191 positive 16S PCR results from the initial 806 tests. Table 1 shows detailed results from Gram stain direct examinations, cultures and 16S rDNA PCR results. In all, 16S PCRs were positive in 80/173 (46%) cardiac valve, 29/71 (41%) abscess, 14/80 (18%) bone, 11/67 (16%) soft tissue, 24/178 (13%) synovial fluid, 13/119 (11%) CSF, 5/27 (19%) pleural fluid, 10/18 (56%) sonication fluid and 5/57 (9%) aqueous humour samples (Table 2).

We found clinical impacts of the 16S PCR results in 62/191 (32%) patients, consisting of 31 (50%) ‘Rationalizing’, 24 (39%) ‘Extended spectrums’ and 7 (11%) ‘Interventions’. Considering all 16S PCR performed in our laboratory during the study period, we estimated the clinical impact to be 8% (62 patients over 806).

In terms of only samples with positive 16S PCR results, the clinical impact differed amongst the various sample types (p = 0.002) (Table 3). Our pairwise analysis showed that positive 16S PCR results were more likely to change patients’ treatments if they had CSF samples than if they had cardiac valve samples (p = 0.044).

The patients’ treatments also altered significantly when considering all the 16S PCR results according to sample types (p = 0.023) (Table 4), but pairwise analysis was not statistically significant. The clinical impact was highest for patients with abscess samples (18%) and sonication fluid samples (22%), but this population was small (18 patients). Conversely, 16S PCR results on soft tissue and aqueous humour samples were less likely to change the patients’ treatments (2/67 or 3% and 2/57 or 4% of clinical impact, respectively). On synovial fluids, CSF, bone, cardiac valve and pleural fluid samples, the impact of a 16S PCR result was intermediary, ranging from 6 to 11%. We did not find any clinical impact on other sample types. Proportion of ‘Rationalizing’, ‘Extended spectrum’ and ‘Interventions’ regarding sample types is described in Table 4.

Table 5 lists all the pathogens identified by 16S PCR. The most frequently identified pathogens were Gram-positive bacteria 125/203 (62%), but the identification of difficult to grow bacteria was more likely to change a patient’s treatment 12/21 (57%). Bacteria were identified to the species level in 189/203 cases (93%).

The proportion of clinical impacts of positive 16S PCR results was significantly superior when blood cultures were negative (52/107, 49%) than when they were positive (10/84, 12%) (p < 0.001). This difference was enlarged in cases of simultaneously negative blood culture and sample’s culture, where positive 16S PCR results changed the patients’ treatments in 44/64 (69%) of cases versus changing only 18/127 (14%) of treatment when at least a bacterium had grown (p < 0.001).

In patients with previous antibiotic therapy, positive 16S PCR results had a high clinical impact. In this subgroup, 92/118 (78%) samples had negative cultures, whereas only 40/73 (55%) samples had negative cultures in patients without previous efficient antibiotic treatments (p < 0.001). We found a clinical impact for the positive 16S PCR results in 33/118 (28%) patients undergoing an efficient antibiotic therapy.

Among 191 positive 16S PCR, blood or sample cultures were positive in 127 cases. The result between PCR and culture was discordant in 38 cases (Table S1). In these situations, 16S PCR results were considered as clinically relevant in 15 cases. For 2 patients, 16S PCR identified an additional bacterium considered by the clinicians. For 7 patients, the bacteria identified by PCR and culture were different and culture was considered as a contamination. For 3 patients, bacteria identified were different and both were considered by clinicians. For 2 patients, the identification was more precise with 16S PCR (i.e. species). For 1 patient, the identification was more precise with 16S PCR, but culture identified one more bacterium considered as a pathogen.

Discussion

This study showed that 32% of our positive 16S rDNA PCR results (62/191) over 5 years had clinical impacts on the patients’ treatment, and this ratio reached 8% when considering all 16S rDNA PCR tests performed (62/806). Sonication fluid, cardiac valve and abscess samples were more likely to lead to positive 16S DNA PCR results than other sample types.

Few studies have evaluated the global clinical impact of 16S PCR: In 2018, O’Donnell et al. found in a retrospective analysis that 16S PCR results modified patients care in 7 of 49 patients (14%); the antibiotic treatments were narrowed in 5 patients and stopped in 2, particularly in those with neurosurgical samples [25]. In another small patient cohort, Akram et al. found in 2017 that 16S PCR results changed patients’ treatments in 9/32 cases (28%); antibiotic therapies were narrowed in 5 cases and stopped in 2 [26].

Considering patients with cardiac valve samples, we found a clinical impact for 16% of the patients with positive 16S PCR results. Regarding every 16S PCR test, the clinical impact was limited to 8% cases. This result is consistent with those of two other studies where 16S PCR results modified patients’ treatments in 10% [27] and 15% [28] of the patients in a prospective cohort of 127 patients and a retrospective cohort of 46 patients, respectively. Conversely, regarding bone and joint infections, we found that positive 16S PCR results greatly led to patients’ treatment modifications in cases with positive synovial fluid (44%, 11/25), bone (43%, 6/14) and sonication fluid (40%, 4/10). Those may be explained by the frequent negativity of cultures in cases of bone and joint samples than in cases of intravascular infections, highlighting the importance of molecular analyzes like the 16S PCR sequencing. Among the 16S PCR results, the clinical impact for synovial fluid, bone and sonication fluid samples were respectively 6, 8 and 22% and higher than expected by a literature review from Saeed et al., where the 16S PCR results provided a microbiological diagnosis in 141/3840 culture-negative prosthetic joint infections (3.7%) [29]. With regard to abscesses, positive 16S PCR results had clinical impacts in 45% cases, even though this technique is theoretically limited when identifying bacteria from polymicrobial samples [30].

Considering only the positive 16S PCR results, we showed that the clinical impact was significantly higher for patients with CSF samples than for those with cardiac valve samples. This can be explained by the low rate of positive cultures and blood cultures in cases of meningitis and the high frequency of neurosurgical infections that can be tough to diagnose and can involve nosocomial pathogens. On the other side, an empirical antibiotic treatment is often started prior to surgery for endocarditis. The lower clinical impact of a 16S PCR-positive result for the management of endocarditis may also be related to the more frequent positivity of blood cultures before any surgical procedures. As a regional reference center for cardiac surgery [31], we admit numerous patients who have had positive blood cultures in peripheral hospitals. Among 80 positive 16S rDNA PCR on cardiac valves, a blood culture was positive from other peripheral hospitals in 28 cases. Nonetheless, we performed 16S PCR tests systematically in our laboratory for patients with cardiac valves when the sample’s cultures are negative despite previous documentation of infection.

As expected, we found that overall, changes in the patients’ treatments were most frequent for patients with negative culture samples, and this may remain the first indication for 16S PCR tests considering the cost of this time-consuming analysis. This is particularly expected in patients pre-treated with empirical antibiotic therapies or in cases of difficult to grow bacteria. More rarely, 16S PCR tests can be helpful even when blood or culture samples are positive to provide a more accurate species identification producing phylogenetic data.

We are aware of our study’s limitations. This was a single center and retrospective study for which bacteriological data were limited to a specific hospital; thus, potentially relevant biases are unavoidable. Secondly, we did not calculate sensitivity, specificity, or predictive positive and predictive negative values of our 16S PCR tests because the study design did not allow it. Our patients had a high probability of presenting bacterial infections, and we did not have a control group representing true negatives. In our laboratory, 16S PCR is currently performed in every cardiac valve with negative cultures when endocarditis is suspected, despite positive blood cultures, which may introduce a selection bias decreasing its clinical impact compared to other sample types. The turnaround time to result of 16S PCRs was not known.

The 16S rDNA PCR test has several limitations itself. Even if using a broad range PCR, the primers are not universal; the choice in the primers and their degenerate oligonucleotides determines the sensitivity for different species [32]. Studies have described a possible persistence of bacterial DNA (especially in cases with previous endocarditis) that could lead to false-positive results [33, 34]. The test’s interpretation should always consider concomitant clinical data. The analysis of chromatograms from polymicrobial infections can reveal itself difficult using Sanger’s sequencing [30], and samples should always be collected from normally sterile sites only.

Conclusion

To conclude, 16S PCR is a useful tool for managing patients with infections, particularly when standard cultures are negative and for those with CSF samples, bone and joint infections or abscesses. This tool is probably cost-effective and clinically relevant if patients and samples are carefully selected.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Change history

18 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05938-7

Abbreviations

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- MALDI-TOF MS:

-

Matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- rDNA:

-

Ribosomal DNA

References

Kollef MH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest. 1999;115:462–74.

Lodise TP, Patel N, Kwa A, Graves J, Furuno JP, Graffunder E, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3510–5.

Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Teng JLL, Tse H, Yuen K-Y. Then and now: use of 16S rDNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification and discovery of novel bacteria in clinical microbiology laboratories. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:908–34.

Rampini SK, Bloemberg GV, Keller PM, Büchler AC, Dollenmaier G, Speck RF, et al. Broad-range 16S rRNA gene polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of culture-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1245–51.

Cunha BA. Antibiotic side effects. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:149–85.

Talpaert MJ, Gopal Rao G, Cooper BS, Wade P. Impact of guidelines and enhanced antibiotic stewardship on reducing broad-spectrum antibiotic usage and its effect on incidence of Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2168–74.

Garbee DD, Pierce SS, Manning J. Opportunistic fungal infections in critical care units. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;29:67–79.

Gyssens IC. Antibiotic policy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2011;38 Suppl:11–20.

Greub G, Lepidi H, Rovery C, Casalta J-P, Habib G, Collard F, et al. Diagnosis of infectious endocarditis in patients undergoing valve surgery. Am J Med. 2005;118:230–8.

Voldstedlund M, Nørum Pedersen L, Baandrup U, Klaaborg KE, Fuursted K. Broad-range PCR and sequencing in routine diagnosis of infective endocarditis. APMIS. 2008;116:190–8.

Miller RJH, Chow B, Pillai D, Church D. Development and evaluation of a novel fast broad-range 16S ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing assay for diagnosis of bacterial infective endocarditis: multi-year experience in a large Canadian healthcare zone and a literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:146.

Kommedal Ø, Wilhelmsen MT, Skrede S, Meisal R, Jakovljev A, Gaustad P, et al. Massive parallel sequencing provides new perspectives on bacterial brain abscesses. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1990–7.

Schuurman T, de Boer RF, Kooistra-Smid AMD, van Zwet AA. Prospective study of use of PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S ribosomal DNA from cerebrospinal fluid for diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in a clinical setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:734–40.

Fenollar F, Roux V, Stein A, Drancourt M, Raoult D. Analysis of 525 samples to determine the usefulness of PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene for diagnosis of bone and joint infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1018–28.

Gomez E, Cazanave C, Cunningham SA, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Steckelberg JM, Uhl JR, et al. Prosthetic joint infection diagnosis using broad-range PCR of biofilms dislodged from knee and hip arthroplasty surfaces using sonication. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3501–8.

Insa R, Marín M, Martín A, Martín-Rabadán P, Alcalá L, Cercenado E, et al. Systematic use of universal 16S rRNA gene polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing for processing pleural effusions improves conventional culture techniques. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91:103–10.

Joseph CR, Lalitha P, Sivaraman KR, Ramasamy K, Behera UC. Real-time polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of acute postoperative endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012; 153:1031–1037.e2.

Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–71.

Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:654–63.

Velay A, Schramm F, Gaudias J, Jaulhac B, Riegel P. Culture with BACTEC Peds plus bottle compared with conventional media for the detection of bacteria in tissue samples from orthopedic surgery. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68:83–5.

Singhal N, Kumar M, Kanaujia PK, Virdi JS. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: an emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:791.

Argemi X, Riegel P, Lavigne T, Lefebvre N, Grandpré N, Hansmann Y, et al. Implementation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in routine clinical laboratories improves identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci and reveals the pathogenic role of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2030–6.

Meddeb M, Koebel C, Jaulhac B, Schramm F. Comparison between a broad-range real-time and a broad-range end-point PCR assays for the detection of bacterial 16S rRNA in clinical samples. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46:18–25.

Flandrois J-P, Perrière G, Gouy M. leBIBIQBPP: a set of databases and a webtool for automatic phylogenetic analysis of prokaryotic sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-015-0692-z.

O’Donnell S, Gaughan L, Skally M, Baker Z, O’Connell K, Smyth E, et al. The potential contribution of 16S ribosomal RNA polymerase chain reaction to antimicrobial stewardship in culture-negative infection. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99:148–52.

Akram A, Maley M, Gosbell I, Nguyen T, Chavada R. Utility of 16S rRNA PCR performed on clinical specimens in patient management. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57:144–9.

Peeters B, Herijgers P, Beuselinck K, Verhaegen J, Peetermans WE, Herregods M-C, et al. Added diagnostic value and impact on antimicrobial therapy of 16S rRNA PCR and amplicon sequencing on resected heart valves in infective endocarditis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017; 23:888.e1–888.e5.

Marsch G, Orszag P, Mashaqi B, Kuehn C, Haverich A. Antibiotic therapy following polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of infective endocarditis: a single Centre experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20:589–93.

Saeed K, Ahmad-Saeed N. The impact of PCR in the management of prosthetic joint infections. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:957–64.

Kommedal O, Karlsen B, Saebø O. Analysis of mixed sequencing chromatograms and its application in direct 16S rRNA gene sequencing of polymicrobial samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3766–71.

Ruch Y, Mazzucotelli J-P, Lefebvre F, Martin A, Lefebvre N, Douiri N, et al. Impact of setting up an ‘endocarditis team’ on the Management of Infective Endocarditis. Open Forum Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz308.

Frank JA, Reich CI, Sharma S, Weisbaum JS, Wilson BA, Olsen GJ. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2461–70.

Branger S, Casalta JP, Habib G, Collard F, Raoult D. Streptococcus pneumoniae endocarditis: persistence of DNA on heart valve material 7 years after infectious episode. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4435–7.

Lang S, Watkin RW, Lambert PA, Littler WA, Elliott TSJ. Detection of bacterial DNA in cardiac vegetations by PCR after the completion of antimicrobial treatment for endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:579–81.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funds were received for the realisation of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AU and XA designed the study. AU, XA, YR, YH and NL collected the clinical data. AU, XA, FS1 and YR analyzed the data. AU and FS1 performed the microbiological analysis. FS2 performed the statistical analysis. AU wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised and approved the final report. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the French legislation (Jardé law, N°2016–800), the non-opposition of all patients was sought. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived and data used in this study was anonymized before its use. The Strasbourg Hospital Ethic Committee approved this study (reference FC/dossier 2019–27).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An error was identified in the article title. The incorrect title is: Revised version (INFD-D-20-00242): impact of 16S rDNA sequencing on clinical treatment decisions: a single center retrospective study. The correct title is: Impact of 16S rDNA sequencing on clinical treatment decisions: a single center retrospective study. The original article has been corrected.

an error was identified in the article title.The incorrect title is Revised version (INFD-D-20-00242): impact of 16S rDNA sequencing on clinical treatment decisions: a single center retrospective studyThe correct title is:Impact of 16S rDNA sequencing on clinical treatment decisions: a single center retrospective studyThe original article has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

Management of discordant positive results between 16S PCR and culture

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ursenbach, A., Schramm, F., Séverac, F. et al. Impact of 16S rDNA sequencing on clinical treatment decisions: a single center retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 21, 190 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05892-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05892-4