Abstract

Background

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in Gram-negative organisms is now a major concern in Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. This study determined a point-prevalence and genetic profiles of ESBL-producing isolates among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae in Lagos State University Teaching Hospital Ikeja, Nigeria.

Methods

Consecutive non-repetitive invasive multidrug-resistant isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae obtained over a period of 1 month (October 2011) were studied. The isolates were identified using VITEK-2/VITEK MS Systems. Susceptibility testing was performed using E test technique; results were interpreted according to the criteria recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012). ESBL production was detected by E test ESBL method and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Results

During the one-month study period, 38 isolates with ESBL phenotypic characteristics were identified and confirmed by PCR. Of these, 21 (55.3 %) were E. coli, 12 (31.6 %) K. pneumoniae, 3 (7.9 %) Proteus spp., 1 (2.6 %) each M. morganii and C. freundii. Thirty (79 %) harbored blaCTX-M genes. Sequence analysis revealed that they were all blaCTX-M-15 genes. Twenty-nine (96.7 %) of these, also harbored blaTEM genes simultaneously. All the CTX-M-15-producing isolates carried insertion sequence blaISEcP1 upstream of blaCTX-M-15 genes. The E. coli isolates were genetically heterogeneous, while the K. pneumoniae had 98 % homology.

Conclusions

Our point-prevalence surveillance study revealed a high prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae isolates harboring blaCTX-M-15 in the Hospital. Urgent implementation of antibiotic stewardship and other preventive strategies are necessary at this time in our hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gram-negative organisms belonging to the family Enterobacteriacae commonly produce beta-lactamases, which confer resistance to most penicillins but not to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. The genes encoding these beta-lactamases are plasmid-borne, and belong to the TEM-1, TEM-2, and SHV-1 types [1]. Infections caused by members of the family Enterobacteriaceae are treated with cephalosporins, particularly the third-and fourth-generation cephalosporins. However, resistance to these drugs has emerged throughout the world with widespread of resistant strains. By the middle of the 80s, resistance to the expanded-spectrum cephalosporin became evident and various studies have shown that the resistance was mediated by structural mutation in the older enzymes [1, 2].

In Enterobacteriaceae, resistance to cephalosporin is commonly due to production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs). The emergence of ESBLs in Gram-negative organisms is now a major concern worldwide [1], and the presence of these enzymes is among the most important resistance determinants to have emerged in Enterobacteriaceae [3–7]. Most ESBLs are derivatives of TEM and SHV β-lactamase families. Other groups such as PER and CTX-M types have been described [8, 9]. In addition, other β-lactamases, including those belonging to Ambler class B (metallo-β-lactamase), class A (e.g. KPC) or class D (OXA-48), capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems have emerged [10–12].

The literature is awash with evidence of global dissemination of CTX-M type ESBL of pandemic proportion [9, 13, 14]. The production of this enzyme is mediated by the blaCTX-M gene, which confers resistance to the third-generation cephalosporins particularly in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. [15]. Several phenotypic and genotypic studies have documented the emergence of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases as well as the genes encoding their production in Enterobacteriaceae, in Nigeria. However, most of these studies have been on randomly selected E. coli and K. pneumoniae [16–19] and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi [20] and thus the true prevalence of CTX-M in most parts of the country is unknown. In our hospital, cephalosporins are first line antibiotics used in the treatment of Gram-negative sepsis and other infective conditions. A previous study conducted earlier in the same hospital demonstrated high resistance rates among clinically significant species of the family Enterobacteriaceae against the cephalosporins and other β-lactam antibiotics [21]. With such high resistance rates, it is conceivable that CTX-M would also be the dominant ESBL type responsible for this high level of resistance in our hospital.

This study was undertaken to investigate a point-prevalence and genetic profiles of ESBL-producing isolates among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae causing infections in patients on admission in a tertiary hospital in Lagos.

Methods

Bacterial isolates and setting

Thirty-eight consecutive isolates of multidrug-resistant invasive species of the family Enterobacteriaceae were obtained over a period of one month (October 2011), during routine laboratory investigation, from in-patients at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH) located in Ikeja, a suburban part of Lagos. The hospital serves as a referral center for about 6 million Lagosians. It has one adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU), 1 Critical Care Unit (CCU), a dialysis unit and an oncology unit. The age, sex, nationality, previous hospital admissions, and documented travel history were all carefully noted. Duplicate isolates were omitted from the study.

The bacterial isolates were identified by VITEK-2 system (bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO, USA). In addition, when necessary, further confirmation was carried out with VITEK MS, a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) system (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France).

Susceptibility testing

Susceptibility testing of the isolates was performed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of amikacin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefepime, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, colistin, ertapenem, imipenem, gentamicin, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, and tigecycline on Mueller-Hinton agar plates using E test (bioMerieux) technique. A quality control strain, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was included in each run. The results were interpreted according to the break-points and criteria recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012) [22].

Confirmation of ESBL

All the ESBL-producing isolates were phenotypically detected by E test ESBL method using cefotaxime (CT)/cefotaxime combined with clavulanic acid (CTL) and ceftazidime (TZ)/ceftazidime combined with clavulanic acid (TZL) (bioMerieux) and were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In-house ESBL-producing E. coli strain K31 [23] and ESBL-negative strain were included in the test runs as positive and negative controls, respectively.

PCR amplification and sequencing

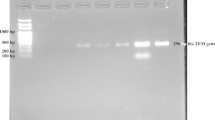

PCR assays were carried out with a series of primers to detect the following genes mediating blaSHV, blaTEM, blaCMY-6, blaCMY-4, and blaCTX-M [24]. PCR products were sequenced with a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Sequences were compared and aligned with reference sequences available in the GenBank.

Detection of insertion sequence, ISEcp1

The genetic organization of the blaISEcp1 was investigated by sequencing this short segment using the following primers: ISEcp1A (5’-GCA GGT CTT TTT CTG CTC C-3’) and ISEcp1B (5’- ATT TCC GCA GCA GCA CCG TTT GC- 3’) [25].

Genotyping of isolates

Fifteen randomly selected strains of the blaCTX-M-15-positive isolates (9 E. coli and 6 K. pneumoniae) were investigated for genetic relatedness using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) with Xba1 digestion of the genomic DNA separated by electrophoresis in 1.2 % agarose gel [26] and the strains compared by differences in number and mobility of the bands.

Results

During this one month study, a total of 73 isolates belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae were studied. Of these, 38 (52.1 %) were ESBL-producing isolates, 21 (55.3 %) of which were E. coli, 12 (31.6 %) K. pneumoniae, 3 (7.9 %) Proteus spp., 1 each (2.6 %) M. morganii and Citrobacter freundii. They were isolated from urine (24), wound swabs (8), blood culture (3) and respiratory secretions (3). These specimens were obtained from infected in-patients who were ethnic Nigerians, predominantly Yorubas. Their ages ranged from 6 – 89 years (mean 59.2 years); 20 (52.6 %) were males and 18 (47.4 %) females with a male-to-female ratio of 1.1:1.

Prevalence of blaCTX-M ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae

The ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae were multidrug-resistant isolates (MDR) showing resistance to five or more antibiotics (Table 1). The number of MDR P. mirabilis, M. morganii and C. freundii isolates was too small for any analysis.

As shown in Table 2, of the 38 ESBL-producing isolates, 30 (79 %) harbored blaCTX-M genes. Sequence analysis of these genes revealed that they were all blaCTX-M-15. Twenty-nine (96.7 %) of these, also harbored blaTEM genes simultaneously. A combination of blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM and blaSHV were found in 6 isolates; the distribution of the blaSHV was blaSHV-11 (2), blaSHV-12 (2) and blaSHV-112 (2). All 30 isolates positive for blaCTX-M carried insertion sequence blaISEcP1 upstream of the blaCTX-M-15 genes.

The ESBL E-test for ESBL production detected all the blaCTX-M, blaTEM and blaSHV-positive isolates confirmed by PCR. Testing both cefotaxime and ceftazidime was necessary for detection of CTX-M-positive isolates. As demonstrated in Table 1, the MIC90s of the third-generation cephalosporins were all >256 μg/ml. Our blaCTX-M-positive isolates, with or without SHV and TEM, were susceptible to amikacin, colistin, imipenem, meropenem and tigecycline. Three isolates (2 E. coli and 1 K. pneumoniae) were not inhibited at the cut-off breakpoint (0.5 μg/ml) of ertapenem but were susceptible to imipenem (MIC = 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml) and meropenem (0.5 and 0.75 μg/ml). There was no specific distribution of the CTX-M-15-positive isolates among ethnic groups of the Yoruba race. Two E. coli and a Proteus spp. isolates were positive for ESBL but the genes encoding their production were not detected.

Clonal relatedness of the blaCTX-M-15 harboring isolates

The fingerprinting of the genomic DNA of the blaCTX-M-15-positive randomly selected isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae showed that the E. coli isolates were genetically heterogeneous, as the isolates did not fall within a particular cluster. On the other hand, there was about 98 % similarity with the K. pneumoniae isolates.

Discussion

The predominant genotype of the ESBL found in the clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in this study was blaCTX-M-type genes with all being blaCTX-M-15; over 96 % of these 38 isolates also harbored a blaTEM β-lactamase gene. Five isolates co-harbored narrow-spectrum blaSHV-11 and other blaSHV genes. Our data demonstrate a very high prevalence of blaCTX-M type ESBL genes among the multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates studied. This lends credence to the worldwide pandemic spread of the CTX-M β-lactamase enzyme, a phenomenon that has reached epidemic proportion among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The ESBL mediated by blaCTX-M type β-lactamase genes are undoubtedly the most widespread enzymes produced among members of this family. This assertion is predicated on the fact that over 79 % of our ESBL-producing isolates harbored blaCTX-M, the gene that mediates CTX-M enzyme production. Remarkably, all the CTX-M enzymes were CTX-M-15, making this type of β-lactamase the most common type detected in Enterobacteriaceae in this Lagos hospital. The dominance of blaCTX-M-15 β-lactamase genes in our snap surveillance study confirms what other workers had earlier reported in North America [15, 27, 28], Europe [29, 30], South America [31] the Middle East [23, 32] and Nigeria [16–20]. This ESBL gene has also been incriminated in community outbreaks of multidrug resistant (MDR) E. coli infections in some parts of the UK [30] and elsewhere [15].

The literature on the genetic characteristics of ESBLs in Nigeria and, indeed, Africa is sparse. The data emanating so far from Nigeria does not include the prevalence of the CTX-M ESBL in an in-patient setting. With this study we have demonstrated that the prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae isolates carrying genes that encode CTX-M-15 ESBL enzymes is at an unacceptable level with potential clinical and financial implications for the hospital.

The clinical implication of this finding is that many patients infected by MDR Gram-negative bacteria stand the risk of treatment failure and cases of fatalities may increase. Thus, treatment of such infections assumes a great challenge to the clinician and the clinical microbiologists as treatment options are limited to very expensive and sometimes toxic drugs. Added to this burden is the fact that the location of the mobile genetic element, ISEcp1, a single copy insertion sequence responsible for mobilization of bla genes, was found upstream of the blaCTX-M genes. This has grave consequences as it might conceivably facilitate the spread of these genes among the Enterobacteriaceae within the hospital. Transfer of the blaCTX-M-15 genes to recipient E. coli J53 has been shown to be quite readily achievable. This suggests that resistance genes can easily move from one species to another with the possibility of easy interspecies transfer. One of the limitations of this study was that plasmids were not studied to determine if these genes were the same.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated an explosive emergence of isolates harboring blaCTX-M-15 gene mediating CTX-M-type ESBL production in invasive members of family Enterobacteriaceae. Immediate implementation of antibiotic stewardship and other preventive strategies are necessary to stem the tide of dangerous spread of MDR Enterobacteriaceae in this Lagos hospital.

Abbreviations

- ESBLs:

-

Extended spectrum beta-lactamases

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute

- LASUTH:

-

Lagos State University Teaching Hospital

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- CCU:

-

Critical care unit

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight

- MS:

-

Mass spectrometry

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

References

Leverstein-van Hall MA, Fluit AC, Paauw A, Box AT, Brisse S, Verhoef J. Evaluation of the Etest ESBL and the BD Phoenix, VITEK 1 and VITEK 2 automated instruments for detection of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase in multi-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3703–11.

Paterson DL, Bonomo R. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86.

Gould IM. Antibiotic policies to control hospital-acquired infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:763–65.

Isaiah IN, Nche BK, Nwagu IG, Nwagu II. Incidence of temonera, sulphuhydryl variables and cefotaximase genes associated with β-Lactamase producing Escherichia coli in clinical isolates. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:557–61.

Peleg AY, Hooper DC. Hospital-acquired infections due to Gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1804–13.

Ogbolu DO, Daini OA, Ogunledun A, Alli AO, Webber MA. High levels of multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Gram-negative pathogens from Nigeria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:62–6.

Mugnaioli C, Luzzaro F, De Luca F, Brigante G, Perilli M, Amicosante G, et al. CTX-M-Type Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in Italy: Molecular Epidemiology of an Emerging Countrywide problem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2700–6.

Poirel L, Naas T, Le Thomas I, Karim A, Bingen E, Nordmann P. CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase that hydrolyzes ceftazidime through a single amino acid substitution in the omega loop. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3355–61.

Pournaras S, Ikonomidis A, Kristo I, Tsakris A, Maniatis AN. CTX-M enzymes are the most common extended-spectrum β-lactamases among Escherichia coli in a tertiary Greek hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:574–5.

Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8.

Poirel L, Heritier C, Tolun V, Nordmann P. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:15–22.

Jamal W, Rotimi VO, Albert MJ, Khodakhast F, Udo EE, Poirel L. Emergence of nosocomial New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Kuwait. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:183–4.

Poirel L, Gniadkowski M, Nordmann P. Biochemical analysis of the ceftazidime-hydrolysing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15 and of its structurally related B-lactamase CTX-M-3. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:1031–4.

Woodford N, Ward ME, Kaufmann ME, Turton J, Fagan EJ, James D, et al. Community and hospital spread of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:735–43.

Boyd D, Tyler S, Christianson S, McGeer A, Muller MP, Willey BM, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kolobase plasmid harbouring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto. Canada Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3758–64.

Soge OO, Queenan AM, Ojo KK, Adeniyi BA, Roberts MC. CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum (beta)-lactamase from Nigerian Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:24–30.

Iroha IR, Esimone CO, Neumann S, Marlinghaus L, Korte M, Szabados F, et al. First description of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-15-extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) in out-patients from South Eastern Nigeria. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:19.

Ogbolu DO, Daini OA, Ogunledun A, Alli OAT, Webber MA. Dissemination of IncF plasmids carrying beta-lactamase genes in Gram-negative bacteria from Nigerian hospitals. J Infect Dev Countr. 2013;7:382–90.

Aibinu I, Odugbemi T, Koenig W, Ghebremedhin B. Sequence type ST131 and ST10 complex (ST617) predominant among CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Nigeria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E49–51.

Akinyemi KO, Iwalokun BA, Alafe OO, Mudashiru SA, Fakorede C. blaCTX-M-1 group extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Salmonella typhi from hospitalized patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:99–106.

Raji MA, Jamal W, Ojemhen O, Rotimi VO. Point-surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from patients in a Lagos Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:431–7.

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 22nd informational supplement MI00-S22. Vol. 32. Wayne, Pennsylvania, PA: CLSI; 2012.

Ensor VM, Jamal W, Rotimi VO, Evans JT, Hawkey PM. Predominance of CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamases in diverse Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from hospital and community patients in Kuwait. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:487–9.

Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Diversity of genetic environment of blaCTX-M genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;234:201–7.

Cao V, Lambert T, Courvalin P. ColE1-like plasmid pIP843 of Klebsiella pneumoniae encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-17. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1212–7.

CDC. Standardized molecular subtyping of foodborne bacterial pathogens by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Atlanta: National Center for Infectious Diseases; 2002.

Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards Jr JE, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. Bad bugs need drugs: an update on the development pipeline from the Antimicrobial Availability Task Force of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:657–68.

Lewis JS, Herrera M, Wickes B, Patterson JE, Jorgensen JH. First Report of the emergence of CTX-M-Type extended-spectrum-beta-lactamases (ESBLs) as the predominant ESBL isolated in a US health care system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4015–21.

Castanheira M, Mendes RE, Rhomberg PR, Jones RN. Rapid emergence of blaCTX-M among Enterobacteriaceae in US medical centres: molecular evaluation from the MYSTIC Program (2007). Microb Drug Resist. 2008;14:211–6.

Livermore DM, Woodford N. The β-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:413–20.

Radice M, Power P, Di Conza J, Gutkind G. Early dissemination of CTX-M-Derived enzymes in South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:602–4.

Al Hashem G, Al Sweih N, Jamal W, Rotimi VO. Sequence analysis of blaCTX-M genes carried by clinically significant Escherichia coli isolates in Kuwait hospitals. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:213–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical staff in the microbiology laboratory at BT Health and Diagnostic Centre Lagos, and Dept. of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait for their support.

Part of this work was presented at the 52nd ICAAC Conference in San Francisco US, 9–12 Sept. 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

MAR conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. WJ, VOR carried out the molecular and data analyses. MAR, OO carried out the phenotypic characterization of the isolates prior to being sent to Kuwait. They were also involved in data collection. VOR, WJ reviewed the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Raji, M.A., Jamal, W., Ojemeh, O. et al. Sequence analysis of genes mediating extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production in isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in a Lagos Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis 15, 259 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1005-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1005-x