Abstract

Backgound

Nurses working in care homes face significant challenges that are unique to that context. The importance of effective resilience building interventions as a strategy to enable recovery and growth in these times of uncertainty have been advocated. The aim of this rapid review was to inform the development of a resource to support the resilience of care home nurses. We explored existing empirical evidence as to the efficacy of resilience building interventions. undertaken with nurses.

Methods

We undertook a rapid review using quantitative studies published in peer reviewed journals that reported resilience scores using a valid and reliable scale before and after an intervention aimed at supporting nurse resilience. The databases; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Medline and PsychInfo. and the Cochrane Library were searched. The searches were restricted to studies published between January 2011 and October 2021 in the English language. Only studies that reported using a validated tool to measure resilience before and after the interventions were included.

Results

Fifteen studies were included in this rapid review with over half of the studies taking place in the USA. No studies reported on an intervention to support resilience with care home nurses. The interventions focused primarily on hospital-based nurses in general and specialist contexts. The interventions varied in duration content and mode of delivery, with interventions incorporating mindfulness techniques, cognitive reframing and holistic approaches to building and sustaining resilience. Thirteen of the fifteen studies selected demonstrated an increase in resilience scores as measured by validated and reliable scales. Those studies incorporating ‘on the job,’ easily accessible practices that promote self-awareness and increase sense of control reported significant differences in pre and post intervention resilience scores.

Conclusion

Nurses continue to face significant challenges, their capacity to face these challenges can be nurtured through interventions focused on strengthening individual resources. The content, duration, and mode of delivery of interventions to support resilience should be tailored through co-design processes to ensure they are both meaningful and responsive to differing contexts and populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The job of nursing is complex and the health and social care environment increasingly challenging [1, 2]. The COVID 19 pandemic has brought these challenges to a different level of complexity resulting in a high psychological burden on nurses [3,4,5]. A job resource and protective factor that can help mediate some of the stresses of these work-based challenges is resilience [6, 7].

Resilience focuses on the positive aspects of individuals to act as a buffer through adversity, to not only allow recovery but enable people to positively manage challenges, learning and adapting from the experience [8, 9]. Resilience may be considered as the ability to adapt to adversity [10] as a dynamic process [11] and an innate resource [12]. The results of a systematic review of resilience interventions concluded that resilience could be conceptualised as mental health in relation to ‘stressor load’ [13]. Our understanding of resilience is informed by a broad systems approach that incorporates the biopsychosocial model of resilience [14] with a socio-ecological perspective [15]. It refers to not only individual capabilities but systems that can ‘neutralise’ adversities and its affects [14] While many definitions of resilience exist, core characteristics of resilience are: the presence of adversity as an antecedent and positive adaptation as a consequence, this differentiates resilience from other more common concepts such as coping and hardiness [16]. Resilience may be seen to differ from coping as it influences the appraisal of a situation before employing specific strategies to cope with the situation [16]. It differs from common understandings of hardiness as when people use the term ‘hardy’ they refer to an ability to withstand stressors but the positive adaptation may or may not be present. As such these concepts relate to resilience but alone do not address its core characteristics. Attributes and assets within and around the person can influence and facilitate this adaptation, this assets-based approach distinguishes resilience interventions from those that look at stress reduction and management of burnout [17].

While resilience is variously interpreted within different populations and contexts [18] a concept analysis of resilience as it applies to nursing defines resilience as the ability to adapt, avoid psychological harm while providing optimum care [19]. Studies highlight that nurse resilience can protect against psychological harm and higher resilience can predict increased levels of happiness, wellbeing and may increase job satisfaction and retention [20, 21]. Reviews of empirical data suggest that resilience can act as a buffer against burnout [22], exhaustion, anxiety, and depression [23]. Interventions aimed at increasing resilience among nurses have proliferated in recent years with resilience considered as core to professional practice [24] and an essential graduate capability [25]. In one of only two studies focusing on care home nurses included in a recent review of nurse resilience [26] resilience was associated with higher perceived quality of care [27]. However, variability in the meaning of resilience and therefore what exactly is being measured prohibits the building of a framework that may help to understand exactly what resilience means as a nurse and what strategies may help build resilience.

Reviews measuring the effectiveness of resilience based interventions have tended to focus on health care workers in general with each recommending that interventions be tailored to specific context and populations [7, 17, 28, 29]. Only two reviews were found relating to the effectiveness of interventions specific to nursing [30, 31]. A mixture of mindfulness, yoga, cognitive reframing exercises, and problem solving exercises formed the basis of resilience interventions. Teaching on how to improve knowledge and response to stress were also significant factors [30, 31]. A meta-analysis of resilience training interventions aiming to influence nurse resilience demonstrated that resilience training increased resilience scores but variations in assessment tools and a variety of outcome measures negated any generalisation of effect [31]. Kunzler et al. extracted studies focusing on nurses from a Cochrane review of psychological intervention to build resilience in health care professionals [17, 30]. They found some evidence of positive short term effects of resilience training and interventions on nurse resilience and mental health outcomes. However as with other reviews in the broader health care literature, the heterogeneity of measurement tools and outcomes assessed made it difficult to decide what elements of an intervention are most effective [7, 17, 30,31,32]. Despite the advocacy for targeted and context specific interventions [7, 13, 17, 33], and the recognition that resilience is a core protective factor against psychological harm [20, 34, 35]. A preliminary scope of the literature revealed no evaluated interventions aimed at supporting nurse resilience specific to the context of the care home. The aim of this rapid review was to inform the development of a resource to support the resilience of care home nurses by extracting empirical evidence as to the efficacy of resilience building interventions undertaken with other nurse populations.

Methodology

The World Health Organisation highlight the importance of timely reviews using rigorous search and transparent reporting measures to inform health policy detailing how and in what settings these programmes work [36]. In a recent overview of definitions, a rapid review is identified as;

"...a form of knowledge synthesis that accelerates the process of conducting a traditional systematic review through streamlining or omitting a variety of methods to produce evidence in a resource-efficient manner.” [37] p80.

A checklist was used in the design, planning, execution, and evaluation of this review to ensure ‘replicability and objectivity’ within a limited time scale [38, 39] (Additional file 2 Brief Review Checklist).

Search strategy

The search was an iterative process with the refinement of the review aims throughout the search process. Measuring resilience as a primary outcome using a valid and reliable tool was the recommendation from reviews looking at resilience across populations. Therefore, in this rapid review a systematic search extracted studies that used a measure of resilience that had undergone psychometric testing to determine reliability and validity as reported in the selected papers. As studies relating to resilience interventions in nurses have emerged primarily in the past 10 years [1] and to understand the current state of evidence, studies published between January 2011 and October 2021 were retrieved from the following sources: The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) sought to extract studies specific to the discipline of nursing. Medline gave a more general picture related to medicine and PsycInfo. gave some insight into the psychological literature therefore including the breadth of the evidence base of the psychological and social sciences. Reference lists of key papers were screened to identify additional studies that met the inclusion criteria (see Table 1).

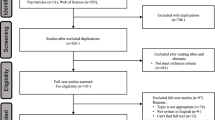

An experienced subject librarian was consulted regarding specific terms and resultant combinations using Boolean operators (OR/AND). The following MESH terms and combinations were used relevant to each database: a. Nurse, (MH) b. Resilience, c. Intervention, d. Evaluation. The systematic search of the databases was undertaken by one author (AM) between September and October 2021. This followed the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) [40]. Initial searches tested the search terms and combinations to ensure retrieval of relevant studies on each database. A full description of the search history for the PsycInfo database is included (Additional file 1 Search PsychInfo). Relevant changes were made to key terms in keeping with the database requirements. The results from the database searches were imported into EndNote v 20 and duplicates were removed. Adapted PRISMA below (Fig. 1) details the search process.

Adapted PRISMA [40] detailing the search and retrieval process

Two authors (AM /CBW) independently reviewed title/abstract of extracted studies using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). The researchers (AM CBW) met and critically appraised the remaining studies inviting support from a third researcher (GM) when differences were difficult to resolve. Reasons for final exclusion are presented in the PRISMA chart [40].

Key data from the final studies were independently extracted and key characteristics placed in a table by AM and CBW under the following headings: a. author/ year and country, b. study objectives, c. population and setting, d. design, e. intervention f. resilience scales and other outcome measures g. duration and h. main study findings. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. A narrative synthesis of the data was undertaken.

Results

A total of 3164 papers were identified. After the removal of duplicates 2919 were screened by title and 578 articles reviewed at abstract. Overall, 26 studies were included for full text review with 11 excluded with reasons. A total of 15 studies were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Fifteen studies were included in this rapid review. Six studies were Randomised control trials [43, 45, 51, 52, 54, 50]. Four studies used Quasi Experimental designs [41, 46, 55, 42]. Five studies used a pre-test post-test survey design [44, 47,48,49, 53]. Most of the studies used convenience sampling with participants self-selected. The participants were mostly female ranging from 71 to 100%. The mean ages of participants when reported varied with mean age over 40 in three studies [47, 49, 50].

Over half of the studies took place in the USA (n = 8) [41, 44,45,46, 50,51,52,53]. Other countries represented were Iran (n = 1) [42], Germany (n = 1) [43], Australia (n = 2 [47, 49], United Kingdom [48], Korea [51] and China [52]. Overall, 1297 registered nurses participated in the studies. While all studies involved registered nurses, one study [44] also included four other healthcare professionals in a sample of 164 at one oncology centre. Therefore, the decision was made to include this study given the small number of non-nurses (4/164). Three studies looked specifically at nurses who were recently registered, two with a view to introducing the intervention as part of a pilot residency programme [41, 45, 46]. The general hospital was the setting for most of the studies with other settings including an oncology centre [44] and an academic medical centre [46, 55]. Within the hospital setting samples from specialist units were recruited such as specialist intensive or critical care units [54, 42], two mental health inpatient units [43, 49] and one unit with transplant nurses and those in leadership roles [53]. All studies aimed to determine the effectiveness of the interventions by changes in resiliency scores using a range of tools that have undergone psychometric testing for reliability and validity namely: the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale [9] (25 item, 10 item and 2 item), the Brief resilient Coping Scale [56], The Ego Resilience Scale [57] and the Workplace Resilience Inventory [58] with several studies using additional secondary outcome measures such as Stress, Compassion fatigue, Depression, Anxiety, Burnout, Satisfaction and Negative Affect.

Demographics and attrition

In some studies where demographic data was reported analysis was undertaken primarily to describe the homogeneity between the populations in control and intervention groups [43, 52, 54]. There was no statistical difference found in the demographic data on resiliency scores in a quasi-experimental study (n = 328) [41]. However in one RCT (n = 196) pre intervention resiliency scores reported older nurses and those with more years in nursing to have higher resiliency scores [50].

Notable was the attrition in studies with larger number of participants [41, 45, 55, 50]. The highest attrition was 60% in a randomised control trial undertaken to determine the effectiveness of a three-hour resiliency community model training with nurses in two tertiary hospitals. Following randomisation only 40% of the sample attended the class or took part in one or more of the follow up surveys [50]. When comparing non attendees and those who attended there was no difference in age, years of experience or secondary traumatic stress scores. The non-attendees had slightly lower well-being and higher somatic stress scores. In a study evaluating the benefits of a tool kit to promote workplace resilience [55] the reasons for high attrition related to time of data collection coinciding with record levels of absenteeism from winter flu and overhauling of email systems. However, in a study replicating this attrition was still 57%, reasons suggested by the authors in discussion with nurse scholars, were that people may have joined to get the toolkit or professional development points [41]. An interesting finding from the pilot study was that when nurse scholars were on the hospital units promoting the resource the attrition level was less [55].

The interventions

The content duration and the delivery of the interventions was variable across studies. Most of the interventions were delivered in groups (n = 13) with individual practice included and encouraged. Only two studies did not involve group activity, one which was a pilot for the larger study [41, 55]. In these two studies a tool kit of items to support resilience was given to participants following a video instruction. The tool kit included an adult colouring book, aromatherapy pen, breathing exercises, and links to various online resources. The participants recorded their use of the kit over 10 shifts using self-report measures relating to level of stress and frequency of use.

Most studies included an element of mindfulness and resiliency training, problem solving, breathing instruction, yoga, cognitive behavioural and interpersonal therapy. Manualised programmes such as Stress management and Resilience training (SMART), promoting adult resilience (PAR) and modifications such as the Mindfulness self-compassion programme (MSC) Mindfulness self-care (MSC) and mindfulness self-care and resiliency programme (MSCR) formed the basis of most interventions [45,46,47,48]. One mindfulness based intervention focused on resilience as a buffer to compassion fatigue [47]. Creative writing, adult colouring and aerobic exercise supplemented training programmes [41, 54, 55]. Some programmes offered links to relevant websites and compact discs of practices to boost resilience with a view to maintaining continuity through the intervention programme [48, 50]. A non-cognitive adaptation of mindfulness formed the basis of The Community Resilience Model (CRM) intervention which focused on developing sensory awareness techniques aiming to achieve emotional balance [50].

While face to face didactic teaching formed a significant part of most interventions a blended learning approach was used in one study [53]. In this study the SMART programme was adopted with the programme delivered in an online format and follow-up in person weekly sessions. To decrease attrition and respond to the busy lives of participants a 7 week manualised programme was adapted to a 2 day face to face programme 3 weeks apart for nurses in an acute mental health unit in Australia [49]. Social media was used for connection, group study and as a platform for hosting group activity in two studies [44, 51] The duration of the studies differed with the shortest being a 3 hour class with access to a mobile application relating to somatic responses to stress [50]. Seven studies were of an 8–12-week duration [43,44,45, 48, 51, 53, 54] with one study incorporating the SMART principles into residency programme monthly for 7 months [46]. Other studies duration were 4–6 weeks to include 10 shifts involving direct patient care [41, 55] and 12 hours over 4 weeks [47]. In one study, five teaching sessions each lasting 90–120 minutes covered aspects of resiliency, what makes a person resilient and how resilience may be supported through specific activities and practices [42]. Almost all studies incorporated some form of didactic instruction, many including individual self-practice and smaller group work. This was reinforced using mobile applications, instruction cards, books, handouts, and social networking. Social media was also used as a platform for smaller private group activity [44, 51]. Figure 2 presents a Word Cloud demonstrating the content and range of interventions outlined in the studies.

Measures of resilience

The Connor Davidson resilience scale (CDRISC) was used in 12 out of the 15 studies, with six studies using the 25-item version [44, 45, 48, 52, 54, 42], five using the 10-item version [41, 46, 47, 55, 50] and one using the two-item version [53]. Of the six studies that used the CDRISC 25 item, five showed significant increases in resilience [44, 48, 52, 54, 42]. Despite an increase in resilience scores in Chesak’s pilot study, no statistical significance was demonstrated [45]. In a quasi-experimental study using the same intervention with novice nurses as part of a residency programme [46] attendance rates increased significantly as did the resilience levels in the intervention groups by comparison to the control group [46]. This was measured using the Connor Davidson 10 item Scale [59]. Four out of five studies measuring resilience with the Connor Davidson 10 item questionnaire reported significant increases in resiliency [41, 46, 55, 50]. The single study that demonstrated no significant changes in resiliency comprised a 12-hour mindfulness based training intervention, including a day workshop on compassion fatigue and weekly training sessions in mindfulness over 4 weeks [47]. The two item CDRISC scale [60] used to measure resilience demonstrated significant increases in resilience scores at T2 and T3 but not immediately after the intervention.

The brief resilient coping scale [56] was used to measure resilience levels at four time points following a 12 week training programme covering stress management, problem solving and solution focused counselling [43]. This demonstrated significant increases in resilience with effect sizes ranging from medium to large. Two further scales were used to evaluate the effects of interventions in the retrieved studies; the ego-resilience scale [57] which showed no significant differences following a 9 week intervention comprising a full day retreat and online or small group ‘huddling programme’ [51]. The Workplace Resilience Inventory (WRI) [58] was used to measure individual resilience factors and demonstrated a strong positive correlation between resilience factors and coping [49].

Discussion

The results of this rapid review of the literature suggest that individual centred resilience interventions can improve nurse resilience. Thirteen of the fifteen studies selected demonstrated an increase in resilience scores as measured by validated and reliable scales demonstrating that the interventions worked in terms of increasing resilience. Previous reviews have highlighted the different interpretations of resilience that relate to protective and risk factors relating to mental health rather than the concept of resilience [13, 17] and the difficulties in determining what exactly is being measured. In this review the Connor Davidson Scale [9] was the primary scale used to measure resilience, this correlates with other reviews of resilience in health care professionals where the CD-RISC was the most commonly used measurement scale [7]. A methodological review of resilience scales found the CD-RISC to be in the top three for psychometric properties [61]. This scale measures resilience as encompassing personal attributes such as self-efficacy, and confidence but also recognises the importance of perception of experience and the importance of interconnectedness [9]. The scale focuses on strengths that enable people to not only recover but thrive in adversity. However as noted by Windle et al. [61] the scale relates to assets and resources, it may be considered to measure the process of resilience rather than resilience as an outcome. The innate nature of resilience makes objective outcome measurement difficult, therefore complementing the quantitative data with qualitative data could help discover what resilience as an outcome looks like and provide culturally and contextually relevant information that could inform the building of a resource for care home nurses.

While the intervention type, population and duration differed between the studies a central focus of the studies was developing self-awareness. Developing self-awareness enhanced control in stressful situations [54]. One of the most reproducible findings in resilience research is that the more control people have over stress situations the less negatively that stress will impact them [62]. Better understanding enabled such control in a study of nurses in a high acuity mental health setting where higher resilience resulted in positive coping following an educational intervention comprising cognitive behavioural and interpersonal therapy [49]. Awareness was developed through a tracking of sense in one study [50] recording of stress levels in another [41, 55] and training to understand stress [43, 45, 46, 42], and decrease compassion fatigue [47]. These individual level interventions aimed to make nurses aware of how stress impacts a person physically, mentally, and socially and how building resilience provides tools that can be transferred and accessed to help deal with adverse situations. As with other reviews of resilience in nursing and across health care demographic data is patchy and conflicting [6, 7]. As the determinants of resilience may be context specific [18] perhaps it is futile to compare across contexts, instead larger samples may provide more robust evidence as to how interventions can be tailored to demographic groups in similar contexts. Care homes nurses work in a unique environment where there is variation in the knowledge and skill set of those providing direct care of the resident [63], coupled with less health care support and high staff turnover [64, 65]. Being cognisant of these broader more structural variables that could impact not only the delivery of interventions but the ethos of the care home is vital in the design and delivery of targeted interventions.

All studies incorporated some element of mindfulness most focusing on a reframing of cognitive processes to focus on acceptance and being present. However, the medium for delivering the mindfulness practice differed and the level of cognitive reframing varied. In one study a large positive association between mindfulness and resilience (r = 0.66) was reported following an 8 week mindful self-compassion training course undertaken in the UK [48]. Mindfulness and resilience have been shown to conceptually overlap, with mindfulness focusing on cultivating positive emotions that help facilitate resilience [66]. The incorporation of mindfulness into a resiliency building programme could help in the reframing of thoughts by enabling.

’A reinterpretation of negative emotions as temporary visitors that will inevitably be replaced by other more welcome guests” [67].

In two studies the use of guided meditation, mind activity books and adult colouring books formed part of an individual intervention [41, 55]. A non-cognitive and novel operationalisation of mindfulness formed the basis of a single intervention lasting 3 h and demonstrating significant improvements in resilience [50]. While it is difficult to identify which of the interventions was most successful due to incomparable sample sizes, duration, and type of intervention, it appears that those interventions that focused on providing immediate ‘on the job’ fixes such as breathing, mindfulness and tracking exercises demonstrated higher scores especially when reviewed over time. Interestingly in one RCT with a multimodal intervention undertaken with nurses in ICU [54] both the control and the intervention group reported significant increases in resilience 1 week after the intervention. This could be explained by the group effect where the control group also benefited from the connectedness of their group. The authors also suggest some overlap with both interventions introducing mindful eating. Indeed, in a synthesis of systematic reviews on resilience in health professionals, feelings of support and connection embedded in workplace culture, significantly influenced individual resilience [68]. It would have been interesting to see if there was a difference between the intervention and control group some months later as this intervention incorporated both reactive (trigger focused CBT) and preventative (nutrition, sleep, exercise) elements. Indeed, in some of the studies that measured resilience at several time points, increases in resilience levels were noted after longer time frames rather than immediately after the intervention [52, 53]. This was also a finding in a RCT involving human service professionals where no instant increase in resilience was noted in the immediate aftermath of the intervention, but significant increases were noted at 4 months [69] suggesting that people who took part started to put into action the strategies they had learned through the intervention. Resilience in nursing viewed as a dynamic process [19] would suggest that time is required to develop skills that positively influence the appraisal of a stress situation and positive coping that results from that appraisal [70]. Indeed, the authors of a four-week intervention that showed no significant change in resiliency scores suggested that the brief duration of the intervention may not fully address the ‘character based ‘processes of resilience [47]. Therefore, longitudinal evaluation of interventions may demonstrate more positive results when participants can realise the benefit of newly acquired skills.

Adherence and engagement with the intervention varied across studies with high attrition levels in some interventions. Recommendations for further research suggest that future studies explore what level of engagement with an intervention is required to ensure a resilient outcome [46]. Informal feedback from one RCT revealed that training should be condensed to 1 day with more booster sessions that would help develop a professional network and enable group activity such as mindfulness [38]. The use of written pamphlets, social media, websites, mobile apps, and games with guides to meditation were used to support many of the interventions. These acted as a prompt to participate in studies, a means of debrief following intervention and as a reminder to self-practice. This is an important consideration in intervention development in promoting user engagement and within the care home setting visual aids in common spaces could act as a prompt to take time to be mindful or just to breathe. A large effect size was demonstrated in one of the included studies of newly qualified nurses where the intervention was incorporated into the residency programme and delivered over 7 months [46]. A programme delivered over a longer time span may address some of the concerns over the ability to influence the innate aspect of resilience with short interventions [7]. While none of the interventions were based totally online, the high attrition involved in many of the reviewed studies point to a need for alternate methods of intervention delivery. In a study of the acute effects of online mind-body skills training on resilience, mindfulness, and empathy (n = 513), the online training was seen to reach and positively affect the resilience levels of a diverse population and in particular those individuals who were stressed [71].

While interested in participating and getting immediate benefits, follow up engagement in some studies was low suggesting interventions should be flexible, readily accessible allowing engagement ‘where they are at’ [72]. Interestingly to address attrition Andersen [41] changed to a pen and paper record of resource use but this made no difference to attrition suggesting that the online recording was not an issue. The use of online and mobile technologies as a platform for delivering resilience interventions may be more cost effective and may reach a greater audience [73]. While this may be a way of minimising disruption in the care home environment where staffing levels are a constant challenge, some consideration needs to be given to the digital capability of the home and care home nurses. A negative correlation between age and informatics was reported in a review of issues affecting nurses ability to use digital technology [74]. In a recent review of care home nurses undertaken by the Queens Institute, 78% of nurses were aged over 45 yrs. [75], therefore interventions should be designed around available resources and may need to incorporate some learning on technologies. Reviews on the efficacy of interventions to foster resilience among health care professionals [17, 76] and other reviews specific to well-being in care home workers [33] suggest that co-designed adequately powered interventions will be more effective as the participants have local knowledge and can advocate for further resources if they are invested in the design and development of the resource.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Limitations relate both to the review process and the individual studies extracted for review. Some of the reviewed studies used small sample sizes. As the influence of demographics on resilience in nursing is conflicting [6] adequate sample sizes with detailed demographics would provide more robust evidence of intervention effect and where interventions need to be tailored to support particular groups. The review is limited in not considering the most recent studies that are been developed or piloted, however the study time frame and funding did not allow for further searches.

As this was a rapid review of the literature and included reliable and validated scales a detailed quality assessment was not undertaken. The use of validated scales to measure resilience pre and post intervention primarily through quasi-experimental designs using valid and reliable tools adds rigour to the review. This provides best evidence as to the effect of individual interventions with the choice of the Connor Davidson Resilience scale in most studies addressing issues of varied interpretation of resilience. The scale authors are clear in their asset-based interpretation of resilience as the ability to positively adapt and potentially thrive in adversity [9]. While other reviews have noted findings as preliminary because of the use of pilot studies [7], two studies in this review were built on earlier pilot data with a resultant improvement in resiliency scores [41, 46]. The main improvements related to increasing the duration of the intervention and the measurement of longer-term outcomes.

Conclusion

This review aimed to determine the effectiveness of interventions to promote resilience in registered nurses to inform the development of a resource to support the resilience of nurses working in care homes. The findings suggest that resilience can be enhanced through interventions. The high attrition in some larger studies suggests that intervention should be designed with the people who will use the resource, giving them something to take away or use ‘on site’ whenever it is required. Sensory awareness and multimodal interventions appeared to be more successful, perhaps appealing to different styles of learning and engagement. Integrating resilience training into programmes for new nurses might allow for the gradual development of resilience as a core capability. Care homes are heterogeneous in terms of staff, levels of care, location, and organisational structures [77], therefore, interventions aimed at supporting care home nurses need to be flexible and may benefit from co-design involving practitioners at a local level to champion the intervention [33, 76]. The results of this brief review show that resilience can be influenced positively through interventions, this knowledge can be used to inform the content of interventions in partnership with care home nurses who will know how best how they may be engaged in the unique context of the care home environment.

Availability of data and materials

The supporting data are published in the body of the review and supplementary files.

Abbreviations

- CDRISC:

-

Connor Davidson Resilience Scale

- RCT:

-

Randomised Control Trial

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- U.K:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Stacey G, Cook G. A scoping review exploring how the conceptualisation of resilience in nursing influences interventions aimed at increasing resilience. Int Pract Dev J. 2019;9(1):1–16.

Hart PL, Brannan JD, De Chesnay M. Resilience in nurses: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag (John Wiley & Sons, Inc). 2014;22(6):720–34.

Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642.

Zhang X, Jiang X, Ni P, Li H, Li C, Zhou Q, et al. Association between resilience and burnout of front-line nurses at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: positive and negative affect as mediators in Wuhan. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(4):939–54.

da Silva Neto RM, Benjamim CJR, de Medeiros Carvalho PM, Neto MLR. Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110062.

Yu F, Raphael D, Mackay L, Smith M, King A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:129–40.

Cleary M, Kornhaber R, Thapa DK, West S, Visentin D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2000;71:247–63.

Manzano García G, Ayala Calvo JC. Emotional exhaustion of nursing staff: influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(1):101–7.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82.

Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, Iversen L, Murchie P, Porteous T, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(647):e423–e33.

Luther S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work child development. 2000;71(3):543–62.

Grafton E, Gillespie B, Henderson S. Resilience: the power within. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(6):698–705.

Chmitorz A, Kunzler A, Helmreich I, Tüscher O, Kalisch R, Kubiak T, et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience–a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:78–100.

Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, Chaudieu I. Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(5):479–95.

Stokols D, Lejano RP, Hipp J. Enhancing the resilience of human–environment systems: a social ecological perspective. Ecol Soc. 2013;18(1):7-18.

Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12.

Kunzler AM, Helmreich I, Chmitorz A, Konig J, Binder H, Wessa M, et al. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD012527.

Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: a handbook of theory and practice. New York: Springer; 2011.

Cooper AL, Brown JA, Rees CS, Leslie GD. Nurse resilience: a concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(4):553–75.

Ang SY, Hemsworth D, Uthaman T, Ayre TC, Mordiffi SZ, Ang E, et al. Understanding the influence of resilience on psychological outcomes — comparing results from acute care nurses in Canada and Singapore. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;43:105–13.

Arrogante O, Aparicio-Zaldivar E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: the mediational role of resilience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:110–5.

Deldar K, Froutan R, Dalvand S, Gheshlagh RG, Mazloum SR. The relationship between resiliency and burnout in Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. 2018;6(11):2250–6.

Finstad GL, Giorgi G, Lulli LG, Pandolfi C, Foti G, León-Perez JM, et al. Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: a narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9453.

Moroney T, Strickland K. Resilience: is it time for a rethink? Aust J Adv Nurs. 2021;38(2):1–2.

Sanderson B, Brewer M. What do we know about student resilience in health professional education? A scoping review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;58:65–71.

Cooper AL, Brown JA, Leslie GD. Nurse resilience for clinical practice: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs (John Wiley & Sons, Inc). 2021;77(6):2623–40.

Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Ghandehari OO, Malloy DC, Hunter PV, Martin RR. Resilience and organisational empowerment among long-term care nurses: effects on patient care and absenteeism. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(3):300–8.

Velana M, Rinkenauer G. Individual-level interventions for decreasing job-related stress and enhancing coping strategies among nurses: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:708696.

Elliott KEJ, Stirling CM, Martin AJ, Robinson AL, Scott JL. We are not all coping: a cross-sectional investigation of resilience in the dementia care workforce. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1251–64.

Kunzler AM, Chmitorz A, Röthke N, Staginnus M, Schäfer SK, Stoffers-Winterling J, et al. Interventions to foster resilience in nursing staff: a systematic review and meta-analyses of pre-pandemic evidence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022; 134:104312.

Zhai X, Ren L-n, Liu Y, Liu C-j, Su X-g, Feng B-e. Resilience training for nurses: a Meta-analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(6):544–50.

Joyce S, Shand F, Tighe J, Laurent SJ, Bryant RA, Harvey SB. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e017858.

Johnston L, Malcolm C, Rambabu L, Hockely J, Shenkin S. Practice based approaches to supporting the work related wellbeing of frontline care workers in care homes: a scoping review. J Long-Term Care. 2021:230-40.

Delgado C, Upton D, Ranse K, Furness T, Foster K. Nurses’ resilience and the emotional labour of nursing work: an integrative review of empirical literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;70:71–88.

Baskin RG, Bartlett R. Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2021;28:28.

Tricco AC, Garritty CM, Boulos L, Lockwood C, Wilson M, McGowan J, et al. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;126:177–83.

Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Defining rapid reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:74–85.

Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM, Wade CA, Tamim R, Persson T, et al. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evid Policy: J Res Debate Pract. 2010;6(3):371–89.

Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE, Organization WH. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide: Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

Andersen S, Mintz-Binder R, Sweatt L, Song H. Building nurse resilience in the workplace. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;59:151433.

Babanataj R, Mazdarani S, Hesamzadeh A, Gorji MH, Cherati JY. Resilience training: effects on occupational stress and resilience of critical care nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25(1):e12697.

Bernburg M, Groneberg DA, Mache S. Mental health promotion intervention for nurses working in German psychiatric hospital departments: a pilot study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(8):706–11.

Blackburn LM, Thompson K, Frankenfield R, Harding A, Lindsey A. The THRIVE© program: building oncology nurse resilience through self-care strategies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47(1):E25–34.

Chesak SS, Bhagra A, Schroeder DR, Foy DA, Cutshall SM, Sood A. Enhancing resilience among new nurses: feasibility and efficacy of a pilot intervention. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):38–44.

Chesak SS, Morin KH, Cutshall SM, Jenkins SM, Sood A. Feasibility and efficacy of integrating resiliency training into a pilot nurse residency program. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;50:102959.

Craigie M, Slatyer S, Hegney D, Osseiran-Moisson R, Gentry E, Davis S, et al. A pilot evaluation of a mindful self-care and resiliency (MSCR) intervention for nurses. Mindfulness. 2016;7(3):764–74.

Delaney MC. Caring for the caregivers: evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses’ compassion fatigue and resilience. PloS One. 2018;13(11):ArtID e0207261.

Foster K, Shochet I, Wurfl A, Roche M, Maybery D, Shakespeare-Finch J, et al. On PAR: a feasibility study of the promoting adult resilience programme with mental health nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(5):1470–80.

Grabbe L, Higgins MK, Baird M, Craven PA, San FS. The community resiliency model® to promote nurse well-being. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(3):324–36.

Im SB, Cho MK, Kim SY, Heo ML. The huddling Programme: effects on empowerment, organisational commitment and ego-resilience in clinical nurses - a randomised trial. J Clin Nurs (John Wiley & Sons, Inc). 2016;25(9–10):1377–87.

Lin L, He G, Yan J, Gu C, Xie J. The effects of a modified mindfulness-based stress reduction program for nurses: a randomized controlled trial. Workplace Health Saf. 2019;67(3):111–22.

Magtibay DL, Chesak SS, Coughlin K, Sood A. Decreasing stress and burnout in nurses: efficacy of blended learning with stress management and resilience training program. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(7/8):391–5.

Mealer M, Conrad D, Evans J, Jooste K, Solyntjes J, Rothbaum B, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a resilience training program for intensive care unit nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2014;23(6):e97–e105.

Mintz-Binder R, Andersen S, Sweatt L, Song H. Exploring strategies to build resiliency in nurses during work hours. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2021;51(4):185–91.

Sinclair VG, Wallston KA. The development and psychometric evaluation of the brief resilient coping scale. Assessment. 2004;11(1):94–101.

Block J, Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(2):349.

McLarnon MJ, Rothstein MG. Development and initial validation of the workplace resilience inventory. J Pers Psychol. 2013;12(2):63.

Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28.

Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JRT. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 2007;152(2–3):293–7.

Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):8.

Vinkers CH, Van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Branchi I, Cryan JF, Domschke K, et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:12–6.

Dudman J, Meyer J, Holman C, Moyle W. Recognition of the complexity facing residential care homes: a practitioner inquiry. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(6):584–90.

Costello H, Walsh S, Cooper C, Livingston G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(08):1203–16.

Comas-Herrera A, Glanz A, Curry N, Deeny S, Hatton C, Hemmings N, et al. The COVID-19 long-term care situation in England: LTCcovid org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE; 2020.

Aydin Sünbül Z, Yerin GO. The relationship between mindfulness and resilience: the mediating role of self compassion and emotion regulation in a sample of underprivileged Turkish adolescents. Personal Individ Differ. 2019;139:337–42.

Polizzi C, Lynn SJ, Perry A. Stress and coping in the time of COVID-19: pathways to resilience and recovery. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):59-62.

Huey CWT, Palaganas JC. What are the factors affecting resilience in health professionals? A synthesis of systematic reviews. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):550–60.

Pidgeon AM, Ford L, Klaassen F. Evaluating the effectiveness of enhancing resilience in human service professionals using a retreat-based mindfulness with Metta training program: a randomised control trial. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(3):355–64.

Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12.

Kemper KJ, Khirallah M. Acute effects of online mind-body skills training on resilience, mindfulness, and empathy. J Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;20(4):247–53.

Lewis M, Palmer VJ, Kotevski A, Densley K, O'Donnell ML, Johnson C, et al. Rapid design and delivery of an experience-based co-designed mobile app to support the mental health needs of health care workers affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: impact evaluation protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(3):e26168.

Baños RM, Etchemendy E, Mira A, Riva G, Gaggioli A, Botella C. Online positive interventions to promote well-being and resilience in the adolescent population: a narrative review. Front Psych. 2017;8:10.

Brown J, Pope N, Bosco AM, Mason J, Morgan A. Issues affecting nurses’ capability to use digital technology at work: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2801–19.

QNI the Queens nursing Institute: The Experience of Care Home Staff During Covid-19 A Survey Report by the QNI’s International Community Nursing Observatory. 2020. [Available from: https://qni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Experience-of-Care-Home-Staff-During-Covid-19-2.pdf. Accessed 25th October 2021.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Cheyne J, Cowie J, Davis B, McCallum J, et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(11). Available at https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013779.

Devi R, Goodman C, Dalkin S, Bate A, Wright J, Jones L, et al. Attracting, recruiting and retaining nurses and care workers working in care homes: the need for a nuanced understanding informed by evidence and theory. Age Ageing. 2021;50(1):65–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the Burdett Trust for Nurses as part of a grant awarded to co-design a resource to support the resilience of care home nurses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design AM, CBW, GM, GC, DMcL. Acquisition of data AM, CBW GM Analysis and interpretation of data AM CBW GM. Preparation and critical revision of the manuscript; AM CBW GM GC DMcL. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search terms (Psych Info database).

Additional file 2.

Brief review checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallon, A., Mitchell, G., Carter, G. et al. A rapid review of evaluated interventions to inform the development of a resource to support the resilience of care home nurses. BMC Geriatr 23, 275 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03860-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03860-y