Abstract

Introduction

Frailty is a complex multifactorial syndrome characterised by a significant increase in vulnerability and worsened health outcomes. Despite a range of proposed frailty screening measures, the prevalence and prognostic value of frailty in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer is not clear.

Aim

The aim of this present review was to examine the use of commonly employed frailty screening measures in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed and Medline was carried out to identify studies reporting the use of frailty screening tools or measures in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. The screening measure used and prevalence of frailty within the population were recorded. Outcomes of interest were the incidence of post-operative complications, 30-day mortality and overall survival.

Results

Of the 15 studies included (n = 97, 898 patients), 9 studies were retrospective and included patients aged 70 years or older (n = 96, 120 patients). 5 of 12 studies reported that frailty was independently associated with the incidence of post-operative complications. There was also evidence that frailty was independently associated with 30-day mortality (1 of 4 studies, n = 9, 252 patients) and long-term survival (2 of 3 studies, n = 1, 420 patients).

Conclusions

Frailty was common in patients with colorectal cancer and the assessment of frailty may have prognostic value in patients undergoing surgery. However, the basis of the relationship between frailty and post-operative outcomes is not clear and merits further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for approximately 12% of new cancer cases diagnosed within the UK each year [1]. Approximately half of all colorectal cancer cases are in patients aged 75 years and over [1]. Furthermore, while age-specific incidence rates vary, the highest rates observed are in the 85 to 89 age group, for both males and females [1]. Advanced age is associated with recognised prognostic factors including co-morbidity [2], sarcopenia [3] and frailty [4]. Therefore, decisions on whether to embark on potentially curative treatment are often complex in older adults with CRC.

Frailty is a complex multifactorial syndrome, characterised by a clinically significant increase in vulnerability and worsened health outcomes [4]. Given the multi-domain character of frailty, with both physical and psychological components contributing to the condition, diagnosing frailty can be difficult for non-experienced clinicians. At present, Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is viewed as the gold standard for diagnosing frailty [5]. The National Institute of Health Consensus Development define CGA as a multidisciplinary evaluation in which the multiple problems of older persons are uncovered, described, explained [6]. This facilitates assessment of the need for enhanced services and the development of a co-ordinated care plan, tailored to the patients. Use of the CGA is advocated in older patients with cancer by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology [7]. Recent cohort studies have shown that older adults patients identified as frail using CGA had significantly increased risk of severe complications [8] and worsened survival outcomes after elective surgery for colorectal cancer [9]. However, CGA is time consuming, with benefit determined by inter-department collaborative care and frailty-targeted optimized intervention programs [10, 11].

In recent years a number of frailty screening measures have been developed to aid physicians in diagnosing frailty [12]. These range in modality, criteria assessed, objectivity and patient participation. Common examples in the current literature range from the simple, image-based Canadian Study of Health and Aging-Clinical Frailty Scale (CSHA-CFS) [13], to the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) Modified frailty indices [14, 15], which combine performance status and co-morbidity, to multi-modal screening measures which include assessments of functional and nutritional status, co-morbidity and subjective, patient-determined elements; examples include the Edmonton Frail Scale [16], Groningen Frailty Indicator [17], Onco-geriatric G8 questionnaire and frailty phenotype [18].

Despite the range of screening measures available, there is a paucity of research examining the prevalence of frailty and the prognostic value of these measures, in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Therefore, the aim of the present systematic review was to examine the use of commonly employed clinical frailty measures in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was developed using PRISMA-P guidelines, including flowchart [19]. The primary outcome of interest was prevalence of frailty, as defined by measures of frailty, in patients with CRC undergoing surgery. The secondary outcome of interest of this systematic review was the association between frailty and clinical outcomes in those undergoing surgery for CRC. Clinical outcomes recorded where the incidence of post-operative complication (using both Clavien-dindo classification or descriptive definitions), 30-day mortality and overall survival. Patient demographic details, TNM stage, frailty measure used and the prevalence of frailty within the population were all recorded.

A literature search was made of the US National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE) and PubMed, from the start of the relevant database to the 3rd of May 2021. The search terms used were related to the following key words: “frailty”, “colon”, “rectal”. “colorectal”, “cancer”, “elderly”, “surgery”, “resection”, “frailty index”, “frailty score”, “Canadian Study of Health and Aging-Clinical Frailty Scale”, “CSHA-CSF”, “Fried frailty phenotype”, “Onco-geriatric screening tool”, “G8 questionnaire”, “Modified frailty index-5” and “MFI-5”, “Modified frailty index-11”, “MFI-11”, “Edmonton Frail Scale”, and “Groningen Frailty Indicator”. The search terms were chosen following multiple pilot searches using more inclusive terms that returned large numbers of abstracts which on initial assessment were irrelevant to the present review topic.

The title and abstracts of all studies returned by the search were examined for relevance by two researchers (JM and RDD). The full text of each study deemed potentially relevant was obtained and analysed. Review articles, non-English papers, duplicate data sets and abstract only results were excluded. To be included a study had to examine the prevalence of frailty, using any of the common frailty scoring measures as previously described, in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Furthermore, the relationship with frailty and post-operative complications, with severity defined by Clavien Dindo classification or descriptive definitions, 30-day mortality or overall survival. Reference lists of included papers, and excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses, were then hand searched for additional relevant studies. Uncertainties in selection and extraction were resolved by discussion with the senior author (DCM), and the final decision made by the senior author. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of included studies.

Assessment of the risk of bias was carried out using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool [20]. Meta-analysis was not performed because of significant heterogeneity among study methodology, populations and outcomes measured. Ethical approval was not required for the present study as this was a systematic review of published data.

Results

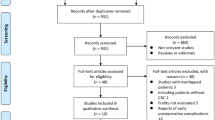

A total of 467 studies were identified on initial search of the Medline and PubMed databases. Following the exclusion of duplicates by the screening of titles, 208 abstracts were reviewed. 49 full papers were then deemed suitable for review, with 15 meeting inclusion criteria for qualitative analysis. Of 34 studies deemed not to meet the eligibility criteria and therefore excluded, reasons include: post-operative outcome measured other than those listed above (n = 13), duplicate publication of the same population (n = 4), inclusion of another cancer subtype in the cohort examining the relationship with frailty and post-operative outcomes (n = 1), cohort included patients with non-cancerous pathology such as inflammatory bowel disease (n = 5), studies in which patients did not undergo surgery or received anti-cancer treatment only (n = 9) and lastly, studies that failed to report the prevalence of frailty or threshold used to define frailty in the population (n = 2) (See Fig. 1).

Qualitive Analysis

Fifteen studies (6 prospective and 9 retrospective, 97, 898 patients) were included in the qualitative analysis (See Table 1). The breakdown of quality of these studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) is shown in Fig. 2. To define frailty, three studies used the CSHA-CFS, three used the G8 questionnaire, two used Fried Frailty phenotype and four used the MFI-5 score. The MFI-11, Groningen frailty index and Edmonton frail scale were each used in one study. Of these studies, twelve reported the incidence of post-operative complications, four studies reported the incidence of thirty-day mortality and three studies reported long-term survival outcomes. In all but two studies reporting the median/mean age [21, 22], the majority included patients aged 70 years or older. Over 80% (n = 81, 803) of patients included were from a single study by Lo and co-workers [23], who found approximately 20% of patients were frail (MFI-5 ≥ 2). Tamura and co-workers reported the highest prevalence of frailty at 56% (n = 278) in a cohort of 500 patients using the G8 questionnaire [24]. 12% was the lowest prevalence of frailty reported in the included studies, in a study by Chen and co-workers of 1928 patients, that used the MFI-5 index [21].

Studies reporting incidence of post-operative complications

The relationship between frailty and post-operative complications is shown in Table 2. Twelve studies including 96,329 patients reported the incidence of post-operative complications in frail patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer [21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Post-operative complications included ranged from CD ≥ 1 in three studies, CD ≥ 2 in four studies and CD ≥ 3 in five studies. In one of the three studies reporting the incidence of grade ≥ 1 complications, frailty was significantly associated with the development of post-operative complications on univariate analysis (p = 0.038, [33]). Three out of the four studies reporting the incidence of grade ≥ 2 complications, found that frailty was associated with the incidence of post-operative complications [26, 31, 32]. Furthermore, this association remained significant on multivariate binary logistics regression analysis in two studies [26, 32]. Lastly, in studies reporting the incidence of serious complications i.e., grade ≥ 3, three reported that frailty was significantly associated with post-operative complications on multivariate binary logistics regression analysis [21, 23, 27]. Of the studies showing an association with frailty and the incidence of post-operative complications on multivariate analysis (See Table 2), the strength of this was found to be moderate in two studies [21, 23] and strong in the other three [26, 27, 32].

Studies reporting incidence of thirty-day mortality

The relationship between frailty and thirty-day mortality is shown in Table 3. Four studies including 9,880 patients reported the incidence of thirty-day mortality in frail patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer [26, 28, 30, 34]. Two studies, one using the CSHA-CFS [34] and the other using the MFI-5 score [26], reported that frailty was significantly associated with thirty-day mortality. In the latter, this association remained significant on multivariate binary logistics regression analysis (p < 0.001, [26]. The strength of the association was found to be strong (OR 20.8, 95% CI 6.2–70.0, P < 0.001, See Table 2). In the remaining two studies, the association was not significant on univariate analysis [28, 30].

Studies reporting overall survival

The relationship between frailty and overall survival is shown in Table 4. Three studies including 1, 569 patients reported the association between frailty and overall survival [22, 34, 35]. Artiles-Armas and co-workers reported a mean follow-up of 5 years only [34]. Mima and co-workers reported a median follow-up of 3.5 years (interquartile range: 2.5–5.1 years, [35]. Feliciano and co-workers reported a median follow-up of 5.8 years (interquartile range: 1 month-19.9 years, [22]. Frailty, defined by the CSHA-CFS and frailty phenotype, was found to be significantly associated with overall survival in two studies (Both, P < 0.001 [22, 35]. In both studies this association was found to be of moderate strength (HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.40–2.99, P < 0.001 and HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.39–2.69, P < 0.001, See Table 4).

Assessment of bias

The ROBINS-I tool was used to assess the risk of bias in included studies. All fifteen of the included studies were deemed at moderate or severe risk of bias overall. Bias due to confounding factors, selection bias and reporting of results was prevalent.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present systematic review examining the relationship between frailty and post-operative outcomes in older adults undergoing surgery for CRC is the most comprehensive to date, including 15 studies totalling 97, 898 patients. The results show that frailty is common in older adults undergoing surgery for CRC and would appear to be moderately and negatively associated with clinical outcomes including the incidence of post-operative complications, 30-day mortality and overall survival. However, due to the limited literature it is still not at present clear which frailty screening measures have clinical utility in the treatment of CRC. Furthermore, the basis of the relationship between frailty and post-operative outcomes is unclear.

Frailty is a spectrum that reflects the systemic, global burden of human aging and erosion of the patients homeostatic reserve [36]. As such one would expect that frailty would be associated with both short- and long-term adverse outcomes. This is in keeping with a recent review by Fagard and co-workers, that included four prospective studies totalling 486 patients, who found that frail patients with CRC were more at risk of adverse outcomes following surgery [37]. However, frailty was only found to be adversely associated with clinical outcomes in 9 of the 15 studies included. The results raise doubts on the reliability of observations in some of the included studies and the clinical utility of certain frailty measures. This highlights the need for frailty screening measures that assess a broad range of domains but are simple and time-efficient enough to be readily employed in clinical practice. Potential examples are the MFI-5 shown to have prognostic value in older adults undergoing surgery for CRC [38, 39] and the CSHA-CFS which is quick to perform, requires limited training of staff and has been shown to have good inter-observer reliability [40, 41].

Frailty is of growing interest and importance across different subspecialities of medicine. It is thought to encompass not only age, but a number of recognised domains including functional status, malnutrition, co-morbidity, cognition, socio-economic and psychological factors [42, 43]. Recent work by Miller and co-workers reported that frailty, but not age, had an independent prognostic value in patients with colorectal cancer [26]. Furthermore, of the seven frailty screening measures included in the present review, only the G8 questionnaire included the assessment of age [44]. The results suggest that simply assessing older adults is insufficient and that those who are functionally restricted, co-morbid or cachexic are likely to also be frail. Indeed, frailty been associated with pre-operative host factors including malnutrition, sarcopenia and inflammation [45]. However, these factors are all independently associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for CRC. Therefore, it remains unclear if frailty per se has independent prognostic value or is simply reflective of the functional and nutritional reserve of the patient to the stress of surgery. Against this background it is of interest that many of the innovations in surgery and anaesthesia in recent decades have been directed at minimising the stressors on the physiological reserve [46]. Indeed, robot assisted surgery has been reported to be associated with better clinical outcomes in older adults with CRC [47, 48].

Frailty and sarcopenia are prevalent and important determinants of functional status and independence in older adults [49, 50]. Indeed, both have been shown to have prognostic value in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer [51, 52]. However, while there is overlap between the conditions [53], the terms are not synonymous. Specifically, sarcopenia is one of many causes of functional impairment- the hallmark of frailty [54]. Therefore, while frailty and sarcopenia may exist independently, whether frailty has independent prognostic value in patients with colorectal cancer is unclear. Further research is required to delineate the relationship between frailty and clinical outcomes, in non-sarcopenic older adults undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer.

Malnutrition, like sarcopenia, is another recognised prognostic factor in those with cancer [55], shown to be prevalent in elderly, frail patients [56, 57]. However, the relationship between malnutrition, muscle mass and functional status in frail patients is poorly understood. Much of the present literature relating to therapeutic interventions in frailty comprises of studies attempting to optimize skeletal muscle mass, with physical activity and nutritional supplementation, to optimize functional status [58,59,60]. Work by Tieland et al. found that dietary protein supplementation improved physical performance in frail patients, but skeletal muscle mass was not increased [61]. Furthermore, work by Bessems et al. demonstrated that frailty, screened using the G8 questionnaire in addition to 4-m gait speed test, was associated with the incidence of post-operative outcomes in a cohort where malnutrition was prevalent [33]. However, the results contrast those of another similar cohort size study from the Netherlands that found the G8 questionnaire had no prognostic value in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer [30]. The disparity between the results of studies suggest that further studies will be required to tease out the relationship between malnutrition, sarcopenia, and functional status in frail patients with cancer.

Inflammation is recognized as one of the seven pillars of aging [62]. A low grade, chronic systemic inflammatory state is observed with advancing age [63]. Recent systematic reviews have shown that frailty is associated with elevated systemic inflammatory markers including CRP and IL-6 [64]. Although, the pathophysiological changes underlying and preceding frailty are not clearly understood, it is plausible that an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response is responsible [64]. Furthermore, systemic inflammation is associated with other recognised domains of frailty including malnutrition [65], sarcopenia and fatigue [66], commonly found in patients with advanced cancer. Therefore, the success of therapeutic interventions to arrest or reverse frailty may require modulation of the systemic inflammatory response, in addition to nutritional supplement and physical exercise [67], as proposed for the pre-habilitation of patients with advanced cancer [68].

There are several limitations of the present systematic review. Firstly, the studies included were mainly retrospective and are therefore subject to confounding factors and selection bias. An example being that patients who were deemed to be frail at diagnosis are more likely to undergo minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, associated with better outcomes in colorectal cancer [46]. Furthermore, those who were deemed to be very frail are unlikely to be considered for surgery and be palliated. Secondly, the absence of a meta-analysis or a pooled prevalence. Neither were considered to be appropriate because of significant heterogeneity of the studies and the large number of observations confined to a few individual studies. Lastly, the majority of studies included in the review were of patients who underwent resection of CRC with curative intent. Therefore, future studies will be required to assess the prevalence and prognostic value of frailty in those with advanced disease.

In conclusion, frailty was common in older adults undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer, across a range of frailty screening measures. Which of these has the greatest utility in clinical practice is unclear and requires further study. Furthermore, while frailty would appear to be moderately associated with post-operative outcomes, the basis of this relationship also remains unclear. Specifically, if frailty per se has an independent prognostic value or is simply reflective of the nutritional and functional reserve of the patient.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data will be made available on request to the senior author (DCM).

References

UK CR. Bowel cancer statistics [Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero.

Wenkstetten-Holub A, Fangmeyer-Binder M, Fasching P. Prevalence of comorbidities in elderly cancer patients. memo - Magazine of European Medical Oncology. 2021;14(1):15–9.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–23.

Tolley APL, Ramsey KA, Rojer AGM, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Objectively measured physical activity is associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;137:218–30.

Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, McCleod A, Arora S, Nockels K, et al. What is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review Age and ageing. 2018;47(1):149–55.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. geriatric assessment methods for clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(4):342–7.

Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, Cohen HJ, Droz JP, Lichtman S, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55(3):241–52.

Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, Skovlund E, Audisio RA, Johannessen H-O, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76(3):208–17.

Ommundsen N, Wyller TB, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, Bakka A, Skovlund E, et al. Frailty is an independent predictor of survival in older patients with colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19(12):1268–75.

Korc-Grodzicki B, Holmes HM, Shahrokni A. Geriatric assessment for oncologists. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12(4):261–74.

Walston J, Buta B, Xue QL. Frailty Screening and Interventions: Considerations for Clinical Practice. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):25–38.

Garcia MV, Agar MR, Soo W-K, To T, Phillips JL. Screening Tools for Identifying Older Adults With Cancer Who May Benefit From a Geriatric Assessment: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):616–27.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):104–10.

Subramaniam S, Aalberg JJ, Soriano RP, Divino CM. New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(2):173-81.e8.

Perna S, Francis MDA, Bologna C, Moncaglieri F, Riva A, Morazzoni P, et al. Performance of Edmonton Frail Scale on frailty assessment: its association with multi-dimensional geriatric conditions assessed with specific screening tools. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):2.

Steverink N. Measuring frailty : Developing and testing the GFI (Groningen Frailty Indicator). Gerontologist. 2001;41:236.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Bmj. 2016;355:i4919.

Chen SY, Stem M, Cerullo M, Gearhart SL, Safar B, Fang SH, et al. The Effect of Frailty Index on Early Outcomes after Combined Colorectal and Liver Resections. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(4):640–9.

Cespedes Feliciano EM, Hohensee C, Rosko AE, Anderson GL, Paskett ED, Zaslavsky O, et al. Association of Prediagnostic Frailty, Change in Frailty Status, and Mortality After Cancer Diagnosis in the Women’s Health Initiative. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2016747.

Lo BD, Leeds IL, Sundel MH, Gearhart S, Nisly GRC, Safar B, et al. Frailer Patients Undergoing Robotic Colectomies for Colon Cancer Experience Increased Complication Rates Compared With Open or Laparoscopic Approaches. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(5):588–97.

Tamura K, Matsuda K, Fujita Y, Iwahashi M, Mori K, Yamade N, et al. Optimal Assessment of Frailty Predicts Postoperative Complications in Older Patients with Colorectal Cancer Surgery. World J Surg. 2021;45(4):1202–9.

Gearhart SL, Do EM, Owodunni O, Gabre-Kidan AA, Magnuson T. Loss of Independence in Older Patients after Operation for Colorectal Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(4):573–82.

Miller SM, Wolf J, Katlic M, D’Adamo CR, Coleman J, Ahuja V. Frailty is a better predictor than age for outcomes in geriatric patients with rectal cancer undergoing proctectomy. Surgery. 2020;168(3):504–8.

Okabe H, Ohsaki T, Ogawa K, Ozaki N, Hayashi H, Akahoshi S, et al. Frailty predicts severe postoperative complications after elective colorectal surgery. Am J Surg. 2019;217(4):677–81.

Reisinger KW, van Vugt JL, Tegels JJ, Snijders C, Hulsewé KW, Hoofwijk AG, et al. Functional compromise reflected by sarcopenia, frailty, and nutritional depletion predicts adverse postoperative outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):345–52.

Richards SJG, Cherry TJ, Frizelle FA, Eglinton TW. Pre-operative frailty is predictive of adverse post-operative outcomes in colorectal cancer patients. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(3):379–86.

Souwer ETD, Verweij NM, van den Bos F, Bastiaannet E, Slangen RME, Steup WH, et al. Risk stratification for surgical outcomes in older colorectal cancer patients using ISAR-HP and G8 screening tools. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(2):110–4.

Suzuki Y, Tei M, Ohtsuka M, Mikamori M, Furukawa K, Imasato M, et al. Effectiveness of frailty screening and perioperative team management of colectomy patients aged 80 years or more. American journal of surgery. 2021.

Tan KY, Kawamura YJ, Tokomitsu A, Tang T. Assessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimized. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):139–43.

Bessems SAM, Konsten JLM, Vogelaar JFJ, Csepán-Magyar R, Maas H, van de Wouw YAJ, et al. Frailty screening by Geriatric-8 and 4-meter gait speed test is feasible and predicts postoperative complications in elderly colorectal cancer patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(4):592–8.

Artiles-Armas M, Roque-Castellano C, Fariña-Castro R, Conde-Martel A, Acosta-Mérida MA, Marchena-Gómez J. Impact of frailty on 5-year survival in patients older than 70 years undergoing colorectal surgery for cancer. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2021;19(1):106.

Mima K, Miyanari N, Morito A, Yumoto S, Matsumoto T, Kosumi K, et al. Frailty is an independent risk factor for recurrence and mortality following curative resection of stage I-III colorectal cancer. Annals of gastroenterological surgery. 2020;4(4):405–12.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Fagard K, Leonard S, Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Wolthuis A, Prenen H, et al. The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(6):479–91.

Simon HL, Reif de Paula T, Profeta da Luz MM, Nemeth SK, Moug SJ, Keller DS. Frailty in older patients undergoing emergency colorectal surgery: USA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):1363–71.

Al-Khamis A, Warner C, Park J, Marecik S, Davis N, Mellgren A, et al. Modified frailty index predicts early outcomes after colorectal surgery: an ACS-NSQIP study. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(10):1192–205.

Flaatten H, Guidet B, Andersen FH, Artigas A, Cecconi M, Boumendil A, et al. Reliability of the Clinical Frailty Scale in very elderly ICU patients: a prospective European study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):22.

Nissen SK, Fournaise A, Lauridsen JT, Ryg J, Nickel CH, Gudex C, et al. Cross-sectoral inter-rater reliability of the clinical frailty scale - a Danish translation and validation study. BMC geriatrics. 2020;20(1):443.

Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, Hurria A. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology Summary. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2018;14(7):442–6.

Dale W, Mohile SG, Eldadah BA, rimble EL, Schilsky RL, Cohen HJ, et al. Biological, Clinical, and Psychosocial Correlates at the Interface of Cancer and Aging Research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(8):581–9.

Soubeyran P, Bellera CA, Gregoire F, Blanc J, Ceccaldi J, Blanc-Bisson C, et al. Validation of a screening test for elderly patients in oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(15):20568.

Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Talley K, Pacala J. The association between geriatric syndromes and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):896–904.

Watt DG, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: Which Components, If Any, Impact on The Systemic Inflammatory Response Following Colorectal Surgery?: A Systematic Review. Medicine. 2015;94(36):e1286.

Ceccarelli G, Andolfi E, Biancafarina A, Rocca A, Amato M, Milone M, et al. Robot-assisted surgery in elderly and very elderly population: our experience in oncologic and general surgery with literature review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(Suppl 1):55–63.

Palomba G, Dinuzzi VP, Capuano M, Anoldo P, Milone M, De Palma GD, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic colorectal surgery in elderly patients in terms of recovery time: a monocentric experience. Journal of Robotic Surgery. 2021.

Morley JE. Sarcopenia: Diagnosis and treatment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(7):452.

Bauer JM, Sieber CC. Sarcopenia and frailty: A clinician’s controversial point of view. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(7):674–8.

Trejo-Avila M, Bozada-Gutiérrez K, Valenzuela-Salazar C, Herrera-Esquivel J, Moreno-Portillo M. Sarcopenia predicts worse postoperative outcomes and decreased survival rates in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(6):1077–96.

Fagard K, Leonard S, Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Wolthuis A, Prenen H, et al. The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2016;7(6):479–91.

Davies B, García F, Ara I, Artalejo FR, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Walter S. Relationship Between Sarcopenia and Frailty in the Toledo Study of Healthy Aging: A Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(4):282–6.

Cooper C, Dere W, Evans W, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R, Sayer AA, et al. Frailty and sarcopenia: definitions and outcome parameters. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(7):1839–48.

Torbahn G, Strauss T, Sieber CC, Kiesswetter E, Volkert D. Nutritional status according to the mini nutritional assessment (MNA)® as potential prognostic factor for health and treatment outcomes in patients with cancer – a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):594.

Verlaan S, Ligthart-Melis GC, Wijers SLJ, Cederholm T, Maier AB, de van der Schueren MAE. High Prevalence of Physical Frailty Among Community-Dwelling Malnourished Older Adults-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(5):374–82.

Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, Regueiro-Folgueira L, Rodríguez-Villamil JL, Millán-Calenti JC. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):108.

Puts MTE, Toubasi S, Andrew MK, Ashe MC, Ploeg J, Atkinson E, et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):383–92.

Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney M-T. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. British Journal of General Practice. 2019;69(678):e61.

Kidd T, Mold F, Jones C, Ream E, Grosvenor W, Sund-Levander M, et al. What are the most effective interventions to improve physical performance in pre-frail and frail adults? A systematic review of randomised control trials. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):184.

Tieland M, van de Rest O, Dirks ML, van der Zwaluw N, Mensink M, van Loon LJ, et al. Protein supplementation improves physical performance in frail elderly people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(8):720–6.

Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, et al. Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease. Cell. 2014;159(4):709–13.

Franceschi C, BonafÈ M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging: An Evolutionary Perspective on Immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908(1):244–54.

Soysal P, Stubbs B, Lucato P, Luchini C, Solmi M, Peluso R, et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;31:1–8.

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia M, Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(1):207–17.

Arends J, Strasser F, Gonella S, Solheim TS, Madeddu C, Ravasco P, et al. Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open. 2021;6(3):100092.

Pansarasa O, Pistono C, Davin A, Bordoni M, Mimmi MC, Guaita A, et al. Altered immune system in frailty: Genetics and diet may influence inflammation. Ageing Research Reviews. 2019;54:100935.

Solheim TS, Laird BJA, Balstad TR, Bye A, Stene G, Baracos V, et al. Cancer cachexia: rationale for the MENAC (Multimodal-Exercise, Nutrition and Anti-inflammatory medication for Cachexia) trial. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8(3):258–65.

Acknowledgements

Nil

Funding

Nil to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Josh McGovern wrote the paper and analysed the data. Ross Dolan aided in writing the paper and statistical analysis. Barry J Laird, Paul G Horgan and Donald C McMillan aided in conceptualization, reviewing, and writing of the paper. Donald C McMillan had primary responsibility for final content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The following review was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was not required for the present study as this was a systematic review of published data.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

Nil to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

McGovern, J., Dolan, R.D., Horgan, P.G. et al. The prevalence and prognostic value of frailty screening measures in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer: observations from a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 22, 260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02928-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02928-5