Abstract

Background

Although some previous studies have reported the impact of cultural factors on individuals’ cognition and decision making, a shortage of research has led to this comparison study for Chinese and Korean elderly, a growing population with depression. This study aimed to explore depression levels in Chinese and South Korean elderly individuals by focusing on testing the generalizability of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).

Methods

The data of 493 community-dwelling Chinese and Korean elderly individuals over the age of 60 years were used to examine GDS. To test the dimensionality, item quality, and reliability of the GDS, the item response theory, Rasch analysis was performed. The detection of differential item functioning (DIF) of the GDS between the two countries was determined by performing a hybrid ordinal logistic regression.

Results

The four-dimensional framework of the GDS, categorized into agitation, cognitive concerns, dysphoria, and vigor/withdrawal was fit for measuring depression levels in Chinese and Korean elderly individuals. In addition, good item quality and reliability of the GDS indicate that almost all items in this scale contribute to measuring the intended trait. Meanwhile, 18 out of 28 items of the GDS were detected as country-related DIF with five items having a large effect size.

Conclusions

Although China and Korea are close geographically and culturally, the item bias shown by severe country-related DIF implies that different cultural backgrounds impact how the elderly interpret GDS items. The cultural issues related to the specific DIF items, the implication to accuracy of individual scores estimation, and the optimal decision to treat individuals were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder in elderly individuals [1]. Although its prevalence differs based on the diagnostic criteria, it is reported to range from 4.5 to 36 %, including subthreshold depressive symptoms [2]. The main attributions of depression in the elderly population include decreased physical functioning, aging-associated diseases, reduced social roles due to retirement, decreased economic status, and isolation or loneliness from the loss of loved ones [1, 3, 4]. In previous research, negative health consequences associated with depression have shown an increased risk of physical and cognitive dysfunction, dementia, cardiovascular and neurologic disorders, suicidal ideation from social isolation, and finally mortality [3, 5]. Additionally, a positive association between increased medical expenses, depression screening, and related treatments has been reported [6,7,8]. Decreased physical and psychological health, social burden caused by depression, and its management worsen the symptoms leading to a lower quality of life [9,10,11]. Considering the current situation of a rapidly increasing aging population [12,13,14], accurate diagnosis of depression and effective treatment planning based on the assessment are essential.

Several self-reported measures assess depression, but the geriatric depression scale (GDS) is one of the most widely used screening tools for the elderly [1, 15]. However, Barua et al. reported that the prevalence of depression in the elderly population varied between 10 % and 20 % worldwide, suggesting that cultural issues are critical considering the challenge of cultural translation regarding the definition of depression in culturally diverse groups [16]. About this issue, Matsumoto argued that cultural background impacts the formation of diverse personal feelings and influences the way people express distress [17]. Additionally, the process of inferential thinking and decision-making may result from comparing themselves with their cultural group, called a reference group effect [18, 19]. It is because culture determines how we assume about, recognize, and interpret the health [20]. In other words, although people have similar symptoms, the reported scores might be different due to the conflation of cultural factors in one’s cognition. Indeed, this phenomenon has been described in previous studies showing different levels of responses to specific psychological tests [20]; nonetheless, Im et al. suggested some additional criteria for the evaluation of cross-cultural studies considering different cultural aspects [21]. It is significance to be aware about culture’s effect on health practice. Given that people from various cultural backgrounds seeking health care facilities undergo psychological tests often to assess their condition at their first visit and follow-up, the responses from self-reported measurements should be comprehensively validated to obtain more accurate data interpretation.

Messick proposed six aspects of construct validity of psychological assessments: content, substantive, structural, generalizability, external, and consequential [22]. These aspects take into consideration the interpretation of the score meaning as well as the consequences of score use. A crucial aspect related to instrument performance to measure respondent trait across different groups was to test generalizability. Particularly, in an international comparison study, the instrument expected to measure the intended trait in the same manner across different groups of participants (e.g., ethnicity, gender, religion) [23]. To test the generalizability of the instrument, differential item functioning (DIF) analyses can be performed. It detects biased items as they may be easier or difficult for a particular group [24]. An instrument with no DIF refers to the standard of measurement, assessing performance without favoring certain individuals [24]. Testing the DIF is fundamental in test development and evaluation.

Previous research reported East Asia countries have culturally interdependent self-construal which possibly affect the increasing stress level [25]. China and Korea have become representative East Asian countries of an aged society that are expected to account for over 30 % of people aged over 60 in the near future [26]. Furthermore, the number of older people with depression or depressive symptoms has been growing in both countries [27, 28]. Depression’s prevalence, assessment, and treatment have been closely linked to sociocultural, economic, and political aspects [29,30,31]. Hence, this study focuses on China and Korea society.

China and Korea show the approval of traditional Confucian values in cultural contexts [32]. Despite sharing common history and culture to a particular degree, both countries potentially exhibit different cultural and social responses. Hofstede cultural dimensions theory well presents the influence of culture on societal value and behavior. According to the findings, the levels of masculinity and uncertainty avoidance in China and South Korea are substantially different (see: www.hofstede-insights.com). China is estimated having higher masculinity, which reflects a more competitive culture where society motivated to be the best in achieving success. Uncertainty avoidance, on the other hand, Korea is estimated showing higher feeling of threatened by ambiguity circumstances, which is linked to how society deals with anxiety. As the East Asian countries, China and Korea included collectivist countries which might prefer to share stressful issues with others. Nonetheless, China has slightly higher levels of individualism. Besides, a cross-cultural comparison study of East Asian countries mentioned that China presents a higher value interpersonal harmony [32], where people have to discipline and express the emotions in diverse relationship to achieve the harmony [32, 33]. Furthermore, China also demonstrated higher tradition and social hierarchy (rules, status, and authorities) [32], and it is accordance to Hofstede’s dimension that China shows higher score of power distance where the culture accepts the inequalities among individuals.

To challenge the assumption of East Asian societies which is viewed to implement the culture and values similarly, this study examines how the different background of society impacts on individual responses of the depression items. Particularly, it explores the validation of GDS focused on testing generalizability of the instrument. The validation for GDS in this international comparison study will help promote cultural knowledge and sensitivity needed from clinical practitioners and researchers, and the results of this study can ultimately be used as the basis for depression assessment and interpretation. Specifically, this study validates the response of individual depression levels measured by the GDS across Chinese and Korean community-dwelling elderly populations with the following research questions:

-

1.

Does the GDS have the best unidimensional or multidimensional frameworks?

-

2.

How well do the GDS items measure traits within underlying constructs?

-

3.

Are the GDS items generalizable across Chinese and Korean participants?

Method

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study design. For the recruitment of elderly individuals, convenience sampling between October 2016 and October 2017 was used. Particularly, data were collected from participants who resided in the two districts of Daejeon city in South Korea and four districts of Xiamen city in China. All participants fulfilled the following requirements: (1) at least 60 years of age, (2) no cognitive impairment, and (3) verbal communication competency. A total of 527 community-dwelling elderly (297 Chinese and 230 Korean) were recruited and 493 people out of them were finally responded (93.5 %) and investigated. The participants were provided written consent to participate in the study, and were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by including a statement in the ethics approval and consent to participate section. All data were obtained through interviews by trained personnel (investigators in this study, senior undergraduate, and graduate students in nursing). They were trained to fill in the Chinese and Korean versions of GDS before starting the data collection in order to verify the authenticity and reliability of the results. When the survey was completed, the questionnaires were checked one by one to verify missing items or ambiguity. The elderly who participated in the survey were given toothbrushes as a token of appreciation. In Table 1, the participants’ characteristics were presented.

Instrument

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), originally developed by Yesavage et al. in 1982, is a self-report instrument used extensively for comprehensive geriatric assessment of depression [34]. It is a close-ended, yes/no response questionnaire comprising 30 items in one-dimensional frameworks. Excluding somatic symptoms, the GDS asks participants about their interest, satisfaction, and worries about life and social activities over the past week. Since the data were collected from Chinese and Korean elderly samples, the Chinese [35, 36] and Korean [37] versions of the GDS were administered for this study. A higher GDS score indicating a higher perception of depression (score range, 0–30). The reliability of Chinese version of GDS was 0.85 (Cronbach’s alpha) and 0.83 (split-half reliability), and 0.81 (test-retest reliability), respectively [36]. Meanwhile, the Cronbach’s alpha and Split-half reliability of Korean version of GDS were 0.88 and 0.79, respectively [37]. Specifically, the correlation value with GDS was 0.87. In addition, KGDS revealed five dimensions with a variance of 53.72 % [37].

Data analyses

Dimensionality, item quality, and reliability

To test the quality of the GDS, two analyses were conducted as follows. First, the dimensionality test was intended to assemble the items coherent with each other and construct the framework of the instrument [38]. We performed item response theory (IRT)-Rasch analyses using ConQuest version 4.14.2. The original GDS with a unidimensionality framework [34], was compared with multidimensional frameworks [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]; the framework with a lower deviance and Akaike information criterion (AIC) value indicated a better model [47,48,49]. This study tested these values on both Chinese and Korean participants, as well as on all participants simultaneously. Second, item quality was tested by investigating the item fit (infit and outfit mean square values [MNSQ]). Item fit explains the item’s function in measuring the trait being measured. The prevalent benchmark to determine the productive measurement is 0.5–1.5. Additionally, the suggested acceptable value is within 0.5–1.7, for clinical observation [48, 50]. The average MNSQ value at 1 means that the estimated model and the data being observed are fitted [48].

With regards to reliability of GDS, the value was explored by analyzing the expected a posteriori/plausible value (EAP/PV) reliability and person separation reliability [51]. The EAP/PV reliability measures the consistency of a set of item difficulties when tested in different respondents with similar abilities [38]. The person separation reliability was comparable to evaluating internal consistency [50, 52], and assumed to be similar to reliability indices such as Cronbach’s alpha. Finally, Cronbach’s alpha of the classical test theory (CTT), broadly used in many studies, was examined to complement the results of the IRT. The reliability value is bounded by 0 and 1, and the closer it is to 1, the less variability of the measurement error [48]. Nevertheless, the value of reliability more than 0.7, includes acceptable consistency [53, 54]. Fischer recommended the following specific categories for the reliability value: excellent (> 0.94), very good (0.91 to 0.94), good (0.81 to 0.91), fair (0.67 to 0.80), and poor (< 0.67) [55].

Non-parametric and parametric DIF: magnitude and impact

The generalizability of the GDS items in the two countries was examined by testing differential item functioning (DIF). DIF detects whether participants with the same traits, coming from different subgroups interpret the item differently [23, 50]. The non-parametric DIF test has been broadly used because it is considered to provide insight into the potential DIF [56]. The Mantel-Haenszel test was performed in this study. A previous study argued that this can only detect non-uniform DIF. However, the non-parametric test is still used by many researchers because it is easily used and understood by readers, and does not require the specification of a model to describe the relationship between item performance and the group variable [57]. The DIF is exhibited if the p-value is less than 0.05 [57]. Researchers employed IRT for DIF detection owing to theoretical and practical considerations in applications [56]. In this study, the parametric DIF was analyzed by performing a hybrid ordinal logistic regression provided by the lordif package [58]. This was considered an advanced DIF analysis because it can detect the type and magnitude of the DIF. By performing lordif, each item forms the null and three nested models with additional explanatory variables [58].

The detection and magnitude of DIF were determined by comparing the probability (χ2) and Nagelkerke effect size values (R2). First, the significant ratio of the likelihood value between models 1 and 2 (df = 1) detected a uniform DIF. The uniform DIF indicated that the effect of DIF was constant for all participants at different levels of the trait. Second, the significant ratio of the likelihood value between models 2 and 3 (df = 1) detected the non-uniform DIF; it refers to the various effects of DIF, which depend on the level of traits. Lastly, the significant ratio of likelihood value between models 1 and 3 (df = 2) indicated the overall DIF/total DIF (uniform and non-uniform). We used the predetermined cut-off of the significant probability value of DIF detection (< 0.01) [58]. Additionally, the magnitude of DIF was determined by the R2 value model comparison. According to Gelin and Zumbo [59], the benchmark is categorized into negligible effect size (< 0.035), moderate effect size (0.035–0.07), and large effect size (> 0.07). Furthermore, the lordif calculated Δβ1 for each item complementing the R2 values to interpret the effect size of the DIF, indicating a meaningful DIF effect if the value is > 0.05.

The lordif produces plots depicting the effect of accumulated DIF on the group and individual scores. The impact of DIF on individual scores can be determined by examining the change in theta estimate with and without the adjustment of DIF or subtraction of purity from the initial theta [58]. The initial theta (unadjusted theta) was generated from the model by accounting for the DIF, and all parameters were set equally for both the groups. Meanwhile, the purified theta (adjusted theta) refers to the score excluding the DIF or the score generated from the model that is estimated separately from the groups [60]. Additionally, both scores were compared using an independent sample t-test to identify significant differences in the scores before and after adjustment.

Results

RQ1. The frameworks of GDS

Table 2 presents the results of the dimensionality test of the GDS based on different frameworks proposed by previous studies. The four-dimensional framework suggested by Haavisto and Boron [42], was the best fit for Chinese elderly population, showing low final deviance and AIC values than those of other models (final deviance = 8159.10, AIC = 8235.10). On the other hand, the dimensionality model proposed by Kim et al. [43], showed a greater fit with Korean elderly population (final deviance = 5313.70, AIC = 5401.70). After combining all participants’ data, the four-dimensionality model proposed by Haavisto and Boron [42], was better for GDS (Final deviance = 14028.57, AIC = 14104.57). Hereinafter, observing Korean data in detail, although the five-dimensional model by Kim et al. [43], showed lower final deviance and AIC, these values were not considered to be significantly different from the four-dimensional model given by Haavisto and Boron [42]. Thus, both frameworks can be assumed to fit Korean elderly individuals. Finally, this study decided on a four-dimensional model for further analyses of the GDS. The four dimensions include agitation, cognitive concerns, dysphoria, and vigor/withdrawal.

RQ2. Item quality and reliability of GDS

Haavisto and Boron [42], mentioned that the items GDS7 and GDS9 were removed from the scale because they comprised only two items in each dimension. This could not substantiate the underlying latent factors for conceptual relevance. Thus, only 28 GDS items were used within the four-dimensional framework. The results of item quality testing revealed that almost all items conformed to a good fit with the Rasch model, except for GDS23 in dysphoria. Table 3 demonstrated the MNSQ range of agitation (infit = 0.92–1.19, outfit = 0.78–1.31), cognitive concerns (infit = 0.96–1.11, outfit = 0.94–1.18), and vigor/withdrawal (infit = 0.83–1.27, outfit = 0.56–1.35). These values are within the cut-off range of 0.5–1.7 for clinical observation. Nonetheless, the range of dysphoria was 0.82–1.46 for infit and 0.66–2.01 for outfit MNSQ. The GDS23 was a misfit because of its outfit MNSQ’s outlier value.

As shown in Table 4, for the reliability values, the results of the person separation reliability of the Chinese, Korean, and combined data were 0.980, 0.981, and 0.987, respectively. It was considered acceptable because the values were more than 0.7; particularly, they were categorized as having excellent reliability based on Fischer’s [55]. Additionally, the results of EAP/PV reliability presented acceptable values (ranging from fair to good), except for the cognitive concerns dimension; the values of Chinese participants and combined data were 0.659 and 0.639 (poor). Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha analysis demonstrated low reliability values for the dimensions of agitation and cognitive concerns, whereas demonstrated good values for dysphoria and vigor/withdrawal dimensions.

RQ 3. Generalizability of GDS items on Chinese and Korean elderly

As presented in Table 5, the results of DIF detection demonstrate that several GDS items were not generalized to the groups of Chinese and Korean participants. Non-parametric analyses revealed 18 DIFs out of 28 GDS items (p < 0.05). Particularly, there were three items each for agitation and cognitive concerns, and six items each for dysphoria and vigor/withdrawal dimension. Additionally, a total of 18 items were flagged as DIF in the parametric analysis (p-value = < 0.01). Three DIF each, were detected in agitation, and cognitive concerns, four in dysphoria, and six in vigor/withdrawal dimension. Among the 18 DIF items, nine items were categorized as uniform DIF (GDS13, GDS29, GDS2, GDS10, GDS23, GDS5, GDS12, GDS20, GDS21), five items as non-uniform DIF (GDS26, GDS25, GDS15, GDS17, GDS19), and four items as overall DIF (GDS6, GDS14, GDS20, GDS28). Most of them were subsets with DIF detected in the non-parametric analysis. GDS3, GDS4, and GDS24 were identified as DIF in the non-parametric analysis, but not in the parametric analysis. Meanwhile, GDS25, GDS15, GDS17, and GDS19 were detected in parametric analysis but not in non-parametric analysis. The details of the detected DIF of the GDS are summarized in the Additional file 1.

The parametric analysis revealed the magnitude of the DIF, presented in Table 6. Of the 18 DIF items, five items were categorized into large effect size (GDS6, GDS29, GDS14, GDS20 in cognitive concerns and vigor/withdrawal), nine into moderate effect size (GDS13, GDS26, GDS23, GDS25, GDS5, GDS12, GDS15, GDS17, GDS28), and four into negligible effect size (GDS2, GDS10, GDS19, GDS21). The results of Δβ1 also presented 11 DIF items (GDS6, GDS13, GDS29, GDS14, GDS20 in cognitive concerns, GDS2, GDS23, GDS5, GDS12, GDS20 in vigor/withdrawal, GDS21), showing a meaningful effect size (value > 0.05).

Figure 1 depicts the visualization of country-related DIF in the form of item characteristic curves (ICCs). The ICCs illustrate the relationship between the trait (depression level) in the theta unit and the probability of the obtained score (item score). This study presented five ICCs of DIF with a large effect size. A big difference can be seen in the scores obtained by Chinese and Korean individuals at the same level of depression (DIF effect). Particularly, GDS6 shows the total effect of the uniform and non-uniform DIF. At the lower level of depression, a constant effect was seen in which Koreans were expected to score lower. Nonetheless, at a higher level of depression (theta > 2), Koreans were estimated to score slightly higher than the Chinese. Additionally, although the figures demonstrate the constant effect of DIF, GDS14 and GDS20 in the cognitive concerns dimension were also included in both uniform and non-uniform DIF. This might be caused by the slight intersection at the lowest and highest levels of depression. As shown in Fig. 1. GDS14 expected Koreans to score lower than Chinese individuals with the same trait, while Koreans were estimated to score higher on GDS20. Furthermore, GDS29 in agitation and GDS20 in the cognitive concerns dimension presented a uniform DIF, whereas Koreans were expected to have a higher score here than the Chinese participants.

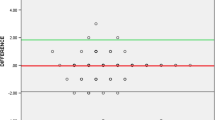

Despite each item’s effect on the expected score, the effect of cumulative DIF on the expected score was visualized in the form of a test characteristic curve (TCC). Figure 2 shows the TCC plots for each dimension. The left plot illustrates a small difference in expected scores between the Chinese and Korean participants across different depression levels as it included all item parameters. On the other hand, the right plots show a more obvious difference in the expected score between the two countries because it only accounted for DIF parameters. The difference between the left and right plots in each dimension indicates that the DIF accounted for in the scoring will affect the expected scores. In the agitation dimension, across different levels of depression, Koreans were estimated to have higher scores than the Chinese (uniform). The dimension of cognitive concerns has a different graph because non-uniform DIF is presented. At lower levels of depression (theta − 4 to -1), Koreans were expected to have slightly higher scores, while Koreans estimated to score lower than Chinese at higher levels of depression (theta − 1 to 2). The dysphoria dimension also shows a uniform DIF since, at every level of depression, Koreans are estimated to score lower than Chinese. Nonetheless, at the theta level of more than 2, Koreans expected to score slightly higher. Lastly, the dimension of vigor-withdrawal demonstrates the non-uniform DIF effect, where at lower levels of depression (theta − 3 to 0), Koreans expected to score higher than Chinese, while they estimated to score lower at higher levels of depression (theta 0 to 4).

The effect of DIF on test characteristic curves (TCC). The left graph labelled with “All Items” shows the expected total score for the two groups computed from both items with and without DIF. The right graph visualizes the differences between Chinese and Korean elderly in only a subset of items with DIF

Furthermore, individual scores before and after adjustment for the DIF effect were obtained. The data of the two countries were compared to reveal that three dimensions, namely agitation, cognitive concerns, and vigor/withdrawal, showed an increase in the p-value from the original score to the adjusted score (see Table 7). Particularly, the agitation dimension presented significantly different scores between Chinese and Korean participants in the original scores and a non-significant score when the adjusted scores were compared. This indicates that the expected scores of the two groups were more similar after the adjustment. Additionally, these three dimensions showed a decreasing effect size (Cohen’s d) and t-value; the dysphoria dimension presented the opposite trend.

Discussion

RQ1. The frameworks of GDS

Before conducting the DIF study, the instrument’s dimensionality framework must be analyzed for the three rationales. First, it must aim to validate the internal structure of the instrument [22] and to assess multiple cognitive dimensions within one assessment [61], ultimately revealing the robust discussion regarding the investigated issue. Second, DIF analysis is performed if the items display good discrimination and show a more homogenous test [62]. It can be presented by the group of items with positive relationships with the total test scores. Accordingly, the items that correlate with each other and measure the same trait should be grouped in the same dimension. Third, as type I measurement errors may occur in a unidimensional analysis [63, 64], the items must be specified based on various measured traits. Nonetheless, previous studies have revealed different multiple frameworks for GDS. Inconsistency in these results may be due to variations in sample characteristics and size. This study revealed that the GDS was consistent with four-dimensional frameworks suggested by Haavisto and Boron [42], including agitation, cognitive concerns, dysphoria, and vigor/withdrawal. First, the agitation dimension comprised five items related to the symptoms of anxiety, asking participants about their worry, fear, or something burdensome in the past and future (e.g., Do you frequently worry about the future?). Second, the cognitive concerns dimension comprised three items (e.g., Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most?) which are similar to the dimension of cognitive impairment in the study by Havins et al. [65]. Third, the dimension of dysphoria comprised ten items associated with dysphoric mood and dissatisfaction with life (e.g., Do you feel that your life is empty?). Fourth, the dimension of vigor/withdrawal comprised ten items related to the level of working energy (physical, emotional, and cognitive liveliness), and emotional difficulties or withdrawal of social interaction (e.g., Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things?). Finally, following the result of factor analysis by Haavisto and Boron [42], GDS20 “Is it hard for you to get started on new projects?”, having a large factor loading to the dimensions of vigor/withdrawal and cognitive concerns, was included in both dimensions for DIF analysis because the lordif can be run if there are at least four items in a dimension.

RQ2. Item quality and reliability of GDS

This study revealed that all GDS items contributed to the meaningful measurement and afforded a well-assessed depression level in the elderly, except for GDS23 in the dimension of dysphoria. It is because GDS 23 revealed a misfit value of the outfit MNSQ. A fit value of more than 1 signifies more variation in the data than the expected Rasch model (data underfit) [48, 50]. Among the items of dysphoria, it is interesting to note that only GDS23 assesses dysphoric mood by comparing oneself to other people (Do you think that most people are better off than you are?). This item was assumed to be responded diversely by respondents, resulting in noise in the data. Boone et al. stated misfitting items can degrade the quality of measurement [50]. Additionally, Linacre claimed that the outfit is more sensitive to outliers/some respondents are strange in some way such as guessing or thoughtless errors [66]. As a result, Boone et al. suggested that participants that contribute to noise in the data should be excluded from analysis [50]. Nonetheless, if the item outfit is too large (i.e. GDS23), Linacre suggested only reporting infit may be appropriate [66]. Thus, some researchers were more concerned with the deviation in infit instead in the outfit value [48]. In addition, the general practice is to keep this item and observe how respondents react to it in future samples to maximize the validity [66].

With regard to the reliability of GDS, good EAP/PV reliability showed a set of item difficulty that would be stable if it was administered to other respondents with the same performance [38]. In fact, the items on cognitive concerns were not reliable when tested in Chinese elderly, consequently influencing the value of combined data [55]. It has been argued that reducing the number of items might decrease the reliability value [49]. This could be the rationale for this study, since the dimension of cognitive concerns comprised three items. Neumann, Neumann and Nehm added that the reliability might not essentially decrease if the dimension has high-quality items [49]. Thus, revision of items is recommended [66]. Additionally, person separation reliability was reported to be excellent, indicating that both Korean and Chinese respondents have excellent consistency in performance if given the same items with the same item difficulty. Nonetheless, Cronbach’s alpha results showed low reliability in the dimension of agitation and cognitive concerns. Person reliability increased for a larger sample size. Therefore, a larger number of respondents are expected to result in better reliability [50].

RQ 3. Generalizability of GDS items on Chinese and Korean elderly

The study findings presented the item bias of GDS, showing different responses to each item of the depression scale by respondents from two different countries, which consequently impacted the performance of different items to assess the two comparable groups. Particularly, this study examined 18 country-related DIF items out of 28 GDS items. The following DIF analysis related issues were noted. First, this study demonstrated that parametric and non-parametric analyses yielded similar results, particularly, the same 14 DIF items in both analyses. Basokcu and Ogretmen also stated that parametric and non-parametric DIF analyses generally generated the same results in the final analysis [67]. The Mantel-Haenszel (non-parametric) was less powerful but was easier to use than logistic regression of IRT (parametric) because it did not need any specification of the model and was free from collinearity problems [56, 57]. As a matter of fact, four out of five non-uniform DIF detected in parametric were not revealed in the non-parametric analysis of this study, supporting the argument regarding the ill-evaluated and non-uniform DIF of the Mantel-Haenszel method [57]. Additionally, in the efficacy of testing non-uniform DIF, the parametric analysis also revealed the graphical application of DIF items. Studies have reported that after comparing various parametric methods, logistic regression has been reported to have the best balance of detecting power and controlling Type I error rate [56, 67]. Second, lordif analysis could be performed if there are at least four items in a dimension; thus, GDS20 was included in both dimensions of cognitive concerns and vigor/withdrawal with consideration of the big factor loading. As a result, GDS20 was exhibited as a DIF with a large effect size in both dimensions, although different values of χ2 and R2 were elicited. Additionally, the ICC plots of GDS20 in the two dimensions showed an identical pattern. In this study, GDS20 was correlated with the dimension of cognitive concerns and vigor/withdrawal, and the combination of other items with GDS20 when analyzing DIF did not elicit a significant impact on the interpretation of GDS20 itself.

Furthermore, only the DIF revealed from the parametric analysis is discussed. Although China and Korea are culturally close, this study demonstrated severe DIF with five DIFs having a large effect size. First, after accounting for DIF for scoring, the Korean elderly were expected to score higher at agitation across different levels of depression. This dimension consisted of two DIF items with a large effect size: GDS6 “Are you bothered by thoughts you can’t get out of your head?” and GDS29 “Is it easy for you to make decisions?” and one DIF item with moderate effect size “GDS13: Do you frequently worry about the future?”. These items are related to perceived feelings of worry, fear, or something burdensome in the past or future. It was reported that there is a large cultural difference between the two countries in terms of uncertainty avoidance, where Korea is more intolerant to ambiguous situations (see www.hofstede-insights.com). High uncertainty avoidance is more threatened by an unknown situation, which consequently prompts worry and social anxiety [68]. As shown in this study, this cultural factor impacts how Koreans who have the same level of worry as Chinese are likely to score higher in filling the self-assessment.

Second, cognitive concerns are one of the main factors affecting depressive symptoms and disorders [69]. Nonetheless, there have been diverse definitions related to the prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment reported by different articles, which has led to the critical challenge of understanding the social burden of this state [70]. Most studies suggest that older age and less education are the main factors associated with mild cognitive impairment [71]. In Korea, it is generally associated with being older, having a lower educational level, and illiteracy [72,73,74]. In China, it was reported that older age, less education [75,76,77], being a woman, having a lower socioeconomic status [75, 78], and living in rural residences [75, 79] had an impact on cognitive impairment. In this study, the effect of cumulative DIF on cognitive concerns showed a non-uniform DIF pattern. At higher trait levels, Koreans were expected to score slightly lower. Thus, we focused on lower levels of cognitive concern where Korean elderly people are estimated to score higher. The Korean elderly compared themselves with society when they were responding to the items of cognitive concerns. Korea undergoes a rapid transition from aging to an aged society. Besides Japan, South Korea was mentioned as one of the fastest aging nations in Asia [74]. The ascending trend of the median age of South Koreans from 1950 to 2050 was reported [80], showing an older population than China [81]. It was found that one-fourth of Koreans over the age of 65 had mild cognitive impairment [82]. Accordingly, it was assumed that an estimated higher score of Korean elderly was the impact of observing the prevalence and incidence of this case in Korean society.

Third, the dysphoria dimension illustrates the non-uniform DIF pattern as the effect of accumulative DIF. A large gap was noted in the lower level of dysphoria, where Korean elderly people were estimated to score lower. Four DIF were elicited from ten items regarding dysphoric mood and dissatisfaction with life: GDS2 “Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?”, GDS10 “Do you often feel helpless?”, GDS23 “Do you think that most people are better off than you are?”, GDS25 “Do you frequently feel like crying?”. Masculinity-femininity culture impacts the explanation of an individual’s emotional adjustment and perceptions [83, 84]. Compared to China, Korea has a feminine culture (see www.hofstede-insights.com), indicating that society places a dominant value on the quality of life and caring for others. Masculine cultures such as China would sacrifice the family and leisure priority for their success, while the feminine culture was associated negatively with unpleasant emotions such as anger and sadness [85, 86]. Higher levels of depression were noted in masculine than in feminine culture [87]. Although Korean and Chinese are included as societies with a restrained culture (inattention to leisure time, indulging is wrong, and controlling the gratification of their desires), China shows a slightly higher score than Korea on restraint culture.

Fourth, the vigor/withdrawal dimension also showed a non-uniform DIF effect with a large gap at a higher level of trait. It was estimated that Koreans scored lower on vigor/withdrawal than the Chinese elderly. This dimension is related to working energy (physical, emotional, and cognitive liveliness) and emotional difficulties or withdrawal of social interaction. Social involvement is a crucial factor impacting dysphoric mood, as well as vigor/withdrawal [88, 89]. As reported, China and Korea are considered collectivist countries. However, China had a slightly higher score for individualism. The more individualist culture, the more self-directed view, autonomous, and independent from others in terms of feeling, behavior, and thought. Previous research has found that individualistic cultures experience more intense extraversion and neuroticism [83, 90, 91]. When eight DIF were accounted for scoring, the elderly in a more collectivist culture with the same level of trait estimated to score lower.

Conclusion and implication

Due to the increase in the elderly population and those with depression, various depression related health issues have gotten attention. This study examined the validation of GDS focus on testing generalizability of items on different countries. The findings showed that the four-dimensional model of geriatric depression scale (GDS) was the best framework to measure the level of depression among Chinese and Korean elderly population. Specifically, the measured traits were categorized into agitation, cognitive concerns, dysphoria, and vigor/withdrawal. The quality of the GDS was presented by fit items in all dimensions, except for GDS23, indicating that almost all items contribute to measuring the intended trait. Additionally, excellent person separation reliability and acceptable item reliability were revealed, except for the cognitive concerns dimension. This study recognized the item bias of GDS, particularly in measuring different patterns of expected scores from the respondents with the same trait coming from two different countries. Although China and Korea are geographically and culturally close, severe DIF in this study implies that different cultural backgrounds impact how the elderly interpret particular items of GDS.

The current study results show that GDS, a representative depression measurement, has significant DIF when used in China and Korea and potentially warn that depression-related research may not be generalized. This issue probably leads to the distortion of the accurate estimation of individual scores and the optimal decision to treat individuals. As the importance of mental health care has emerged particularly since the start of the Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic, more international comparative studies related to depression are expected to be investigated. In this sense, this study may be worthwhile and can be implemented to other scales of depression.

DIF studies have long been conducted in clinical research. It is also true that studies on the biological and sociocultural background related to depression have been conducted. The current study highlighted to address the need for researchers and administrators to be more aware of irrelevant factors that might conflate in patients’ cognition when responding to the self-reported measures. To compare the influence of various factors on depression, studies to assess measurement equivalence is necessary. Additionally, this study recommends the DIF research in another clinical topics such as stress, anxiety, and insomnia by considering irrelevant factors (i.e., gender, socioeconomic status, language, etc.). Therefore, our further study design will concern the bias scores and how they are associated with socio-demographic information. Furthermore, DIF study also can be applied for more than two groups, considering more flexible methods for international comparison studies.

Limitation

Although this study provided comprehensive validation procedures for the instrument, it did not address how to overcome the misfit item, lower reliability value, and how to solve the DIF item. In addition, DIF analysis only examine the item that functions differently to different group of respondents, but it did not examine the cause of DIF. The result of non-uniform DIF was only interpreted based on the large difference in the expected scores and the discussion of DIF was only based on previous literature reviews related to depression in China and Korea. Finally, this study did not explore qualitatively the occurrence of DIF item by conducting an interview to the salience participants (affected by DIF item significantly) to complement the cultural discussion.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-19

- CTT:

-

Classical test theory

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- EAP/PV:

-

A posteriori/plausible value

- GDS:

-

Geriatric depression scale

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- MNSQ:

-

Mean square values

- TCC:

-

Test characteristic curve

References

Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. BMJ. 2011;343:D5219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5219.

Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, et al. A tune in “a minor” can “b major”: a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):126–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.015.

Aziz R, Steffens DC. What are the causes of late-life depression? Psychiatr Clin. 2013;36(4):497–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.001.

Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, et al. Does growing old increase the risk for depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1384–90.

Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):M249-65. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249.

Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):897–903. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897.

Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, et al. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1155–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0032.

Luppa M, Heinrich S, Matschinger H, et al. Direct costs associated with depression in old age in Germany. J Affect Disord. 2008;105(1–3):195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.008.

Cao W, Guo C, Ping W, et al. A community-based study of quality of life and depression among older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7):693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070693.

Cha EJ, Kim KH. Effects of subjective health status on life satisfaction among middle-aged and aged people in Korea: Testing mediating effect of depression. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welfare. 2015;70:53–80.

Cheruvu VK, Chiyaka ET. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care: findings from a nationally representative sample. BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(1):192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1203-2.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexch.htm [Accessed Oct 2020].

Statistics Korea. Statistics on the Aged 2018. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=370779 [Accessed Oct 2020].

U.S. Census Bureau. Older and Growing - Percent Change among the 65 and Older Population: 2010 to 2019. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2020/comm/map-popest-65-and-older.html [Accessed Oct 2020].

Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI‐II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S454-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20556.

Barua A, Ghosh MK, Kar N, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders in the elderly. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(6):620–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.87100.

Matsumoto D. Cultural influences on the perception of emotion. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1989;20(1):92–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022189201006.

Crede M, Bashshur M, Niehorster S. Reference group effects in the measurement of personality and attitudes. J Personal Assess. 2010;92(5):390–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.497393.

Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Peng K, et al. What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: the reference-group effect. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;82(6):903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903.

Christopher S, Christopher JC, Dunnagan T. Culture’s impact on health risk appraisal psychological well-being questions. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24(5):338–48. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.24.5.2.

Im EO, Page R, Lin LC, et al. Rigor in cross-cultural nursing research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(8):891–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.04.003.

Messick S. Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol. 1995;50(9):741–9.

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (AERA, APA, NCME). In: Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: AERA; 2014.

Boone WJ, Scantlebury K. The role of Rasch analysis when conducting science education research utilizing multiple-choice tests. Sci Educ. 2006;90(2):253–69.

Cross SE. Self-construals, coping, and stress in cross-cultural adaptation. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1995;26(6):673–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202219502600610.

World Health Organization (WHO, 2015). World report on ageing and health: World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/ [Accessed Oct 2020].

Ministry of Health and Welfare (2011. 3. 14). The Number of Elderly Depression Patients has Increased 1.7 Times Over the Past Five Years. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=249839&page=9 [Accessed Oct 2020].

Yu J, Li J, Cuijpers P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: a population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(3):305–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2721.

Falicov CJ. Culture, society and gender in depression. J Fam Ther. 2003;25(4):371–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00256.

Lim LL, Chang W, Yu X, et al. Depression in Chinese elderly populations. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2011;3(2):46–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5872.2011.00119.x.

Zhang D. Depression and culture—a Chinese perspective. Can J Counsell Psychother. 1995;29(3):227–33. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/58531.

Zhang YB, Lin MC, Nonaka A, Beom K. Harmony, hierarchy and conservatism: a cross-cultural comparison of Confucian values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Commun Res Rep. 2005;22(2):107–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036810500130539.

Huang LL. Interpersonal harmony and conflict for Chinese people: a yin–yang perspective. Front Psychol. 2016;7:847. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00847.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4.

Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. Handbook of mental health rating scales. Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Journal; 1999. p. 219.

Liu J, Wang W, Wang XH, Song RH, Yi XH. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of geriatric depression scale among Chinese urban community-dwelling elderly population. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2013;21(1):39–41.

Jung IK, Kwak DI, Joe SH, et al. A study of standardization of Korean form of Geriatric Depression Scale (KGDS). J Korean Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;1(1):61–72.

Sbeglia GC, Nehm RH. Do you see what I-SEA? A Rasch analysis of the psychometric properties of the Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance. Sci Educ. 2019;103(2):287–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21494.

Ertan T, Eker E. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the geriatric depression scale in Turkish elderly: are there different factor structures for different cultures? Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(2):163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610200006293.

Galeoto G, Sansoni J, Scuccimarri M, et al. A psychometric properties evaluation of the Italian version of the geriatric depression scale. Depress Res Treat. 2018;2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1797536.

Ganguli M, Dube S, Johnston JM, et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment and functional impairment in a rural elderly population in India: a Hindi version of the geriatric depression scale (GDS-H). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(10):807–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199910)14:10<807::AID-GPS31>3.0.CO;2-%23.

Haavisto W, Boron JB. Examination of discrepancies between subjective and objective memory with latent factors of the geriatric depression scale. Aging Mental Health. 2019;23(4):475–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1428939.

Kim JY, Park JH, Lee JJ, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of the geriatric depression scale: reliability, validity, and factor structure. Psychiatry Investig. 2008;5(4):232:232–38. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2008.5.4.232.

Parmelee PA, Lawton MP, Katz IR. Psychometric properties of the Geriatric Depression Scale among the institutionalized aged. Psychol Assess. 1989;1(4):331. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.4.331.

Pocinho MT, Farate C, Dias CA, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for Portuguese elders. Clin Gerontol. 2009;32(2):223–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317110802678680.

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA, Brooks JO, et al. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(1):23–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610291000480.

Adams R, Wu M. Multidimensional Models. Chapter 10 of the notes and tutorial. ACER conquest version 4 (Computer Software). Camberwell: Australian Council for Educational Research; 2010.

Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. New York: Psychology Press; 2013.

Neumann I, Neumann K, Nehm R. Evaluating instrument quality in science education: rasch-based analyses of a nature of science test. Int J Sci Educ. 2011;33(10):1373–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.511297.

Boone WJ, Staver J, Yale MS. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014.

Wu ML, Adams RJ, Wilson MR, et al. ACER ConQuest version 2.0: Generalised Item Response Modelling Software. Victoria: ACER Press; 2007.

Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Holmefur M, Kottorp A, et al. The Assisting Hand Assessment: current evidence of validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(4):259–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00259.x.

DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication; 2017.

Grigg K, Manderson L. The Australian racism, acceptance, and cultural-ethnocentrism scale (RACES): item response theory findings. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0338-4.

Fisher WP Jr. Rasch measurement transaction. Transact Rasch Measure SIG Am Educ Res Assoc. 2007;21(1):1095.

Lopez GE. Detection and classification of DIF types using parametric and nonparametric methods: a comparison of the IRT-likelihood ratio test, crossing-SIBTEST, and logistic regression procedures [dissertation]. Tempa (FL): University of South Florida, Tempa; 2012.

Teresi JA, Fleishman JA. Differential item functioning and health assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9184-6.

Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK, Lordif. An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and Monte Carlo simulations. J Stat Softw. 2011;39(8):1.

Gelin MN, Zumbo BD. Differential item functioning results may change depending on how an item is scored: An illustration with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Educ Psychol Measure. 2003;63(1):65–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164402239317.

Kleinman M, Teresi JA. Differential item functioning magnitude and impact measures from item response theory models. Psychol Test Assess Model. 2016;58(1):79.

Allalouf A. Revising translated differential item functioning items as a tool for improving cross-lingual assessment. Appl Measure Educ. 2003;16(1):55–73. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1601_3.

Salsman JM, Schalet BD, Merluzzi TV, et al. Calibration and initial validation of a general self-efficacy item bank and short form for the NIH PROMIS®. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(9):2513–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02198-6.

Baştuğ ÖY. A comparison of four differential Item functioning procedures in the presence of multidimensionality. Educ Res Rev. 2016;11(13):1251–61. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2016.2803.

Mazor KM, Hambleton RK, Clauser BE. Multidimensional DIF analyses: The effects of matching on unidimensional subtest scores. Appl Psychol Measure. 1998;22(4):357–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662169802200404.

Havins WN, Massman PJ, Doody R. Factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale and relationships with cognition and function in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34(5–6):360–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345787.

Linacre JM. A User’s Guide to Winsteps [User’s manual and software]. Available from: http://www.winsteps.com/winsteps.htm [Accessed Sept 2020].

Basokcu TO, Ogretmen T. Comparison of parametric and nonparametric item response techniques in determining Differential Item Functioning in polytomous scale. Am J Theoret Appl Stat. 2014;3(2):31–8. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20140302.11.

Boelen PA, Vrinssen I, van Tulder F. Intolerance of uncertainty in adolescents: Correlations with worry, social anxiety, and depression. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2010;198(3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d143de.

Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(5):372–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x.

Ward A, Arrighi HM, Michels S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: disparity of incidence and prevalence estimates. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.002.

Eshkoor SA, Hamid TA, Mun CY, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and its management in older people. Clin Intervent Aging. 2015;10:687. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S73922.

Bae JB, Kim YJ, Han JW, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment in Korean elderly. Dement Geriatr Cognit Disord. 2015;39(1-2):105–15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000366555.

Kim KW, Park JH, Kim MH, et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in South Korea. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(2):281–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-101221.

Lee Y, Shinkai S. Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea and Japan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):576–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1313.

Lu J, Li D, Li F, et al. Montreal cognitive assessment in detecting cognitive impairment in Chinese elderly individuals: a population-based study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2011;24(4):184–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988711422528.

Zou Y, Zhu Q, Deng Y, et al. Vascular risk factors and mild cognitive impairment in the elderly population in Southwest China. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2014;29(3):242–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513517042.

Zhuang JP, Wang G, Cheng Q, et al. Cognitive impairment and the associated risk factors among the elderly in the Shanghai urban area: a pilot study from China. Transl Neurodegen. 2012;1(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-9158-1-22.

Ren L, Zheng Y, Wu L, et al. Investigation of the prevalence of cognitive impairment and its risk factors within the elderly population in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21983-w.

Jia J, Zhou A, Wei C, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and its etiological subtypes in elderly Chinese. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(4):439–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.008.

Plecher H. Median Age of the Population in South Korea 2015. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/604689/median-age-of-the-population-in-south-korea/#professional [Accessed January 2021].

Textor C. Median Age of the Population in China from 1950 to 2100. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/232265/meanage-of-the-chinese-population/ [Accessed Nov 2021].

Kim HR, Yang M. Cognitive impairment and risk factors among elderly persons aged 60 or more in Korea. J Korean Public Health Nurs. 2013;27(3):450–65. https://doi.org/10.5932/JKPHN.2013.27.3.450.

Fernández-Berrocal P, Salovey P, Vera A, et al. Cultural influences on the relation between perceived emotional intelligence and depression. Int Rev Soc Psychol. 2005;18(1):91–107.

Fischer AH, Manstead AS. The relation between gender and emotions in different cultures. Gender Emotion: Soc Psychol Perspect. 2000;1:71–94.

Basabe N, Paez D, Valencia J, et al. Cultural dimensions, socioeconomic development, climate, and emotional hedonic level. Cognit Emotion. 2002;16(1):103–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000158.

Basabe N, Paez D, Valencia J, et al. Sociocultural factors predicting subjective experience of emotion: A collective level analysis. Psicothema. 2000;12(Su1):55–69.

Arrindell WA, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Higher levels of state depression in masculine than in feminine nations. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(7):809–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00185-7.

Toepoel V. Ageing, leisure, and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people?. Soc Indicators Res. 2013;113(1):355–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0097-6.

Utz RL, Carr D, Nesse R, et al. The effect of widowhood on older adults' social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. Gerontologist. 2002;42(4):522–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.4.522.

Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Ann Rev Psychol. 2003;54(1):403–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056.

Schimmack U, Radhakrishnan P, Oishi S, et al. Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: integrating process models of life satisfaction. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;82(4):582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.582.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely thankful to the participants who provided time and shared their health information as well as the community centers who supported our data collection for this study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: IHP and YL; Data collection: YL; Data analysis: IHP and YS; Manuscript writing: IHP, YL, and YS. All authors read the manuscript for important intellectual context and approved the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics approval including participants’ approach and recruitment were granted by the Chungnam National University, Research Center, Republic of Korea (Project Number 2012-86), We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by including a statement in the ethics approval and consent to participate section. We provided the elderly with a letter of introduction and an information sheet about the research, the informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, I.H., Sya’bandari, Y. & Liu, Y. Item bias on the geriatric depression scale (GDS): investigating the quality and generalizability of GDS on Chinese and Korean community-dwelling elderly population. BMC Geriatr 21, 637 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02516-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02516-z