Abstract

Background

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) shows good performance in detecting depression among older persons, but its applicability has not been well studied in non-Western oldest-old adults and centenarians. This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric property of the GDS-15 and a simplified version among a large representative longevous population in China.

Methods

A total of 1624 individuals (786 oldest-old persons aged from 80 to 99 years; 838 centenarians aged 100+ years) participated in this study. Home interviews with structured questionnaires were conducted to collect sociodemographic data. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Chinese GDS-15 version. We implemented mixed methods for the psychometric evaluation of the GDS-15. Cronbach’s α coefficient and item-total correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the internal consistency. A standard expert consultation was conducted to test the content validity of each item. Multiple factor analyses were used to explore the optimal factor structure and measurement invariance.

Results

The α coefficient of the GDS-15 was 0.745, while two items impaired the overall consistency reliability. Nineteen experts rated the applicability for each item and provided removal suggestion. Five items with less validity were removed, and a simplified 10-item GDS model with three-factor structure was proposed as an optimal solution. The GDS-10 model showed factorial equivalence across age, sex, residence, and education in multi-group confirmatory factor analyses.

Conclusions

The original GDS-15 has acceptable internal reliability, known-group validity, and concurrent validity among Chinese community-dwelling oldest-old and centenarians; however we provided preliminary evidence indicating that individual items related to somatic function or social activities may not be applicable for this population. The modified GDS-10 can be proposed as a potentially more practical and comprehensible instrument for depression screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders in later life [1]. Early detection of depression is essential in geriatric care due to its increasing prevalence and detrimental effects among the older people worldwide [2, 3]. Older adults with depression or depressive symptoms face with numerous adverse health outcomes including functional decline, cognitive impairment, decreased quality of life [4, 5]. Previous studies have showed that depressive symptoms were more prevalent in oldest-old than in younger old groups [2, 6]. The decline of function associated with aging is closely related to the psychological symptoms of depression in the oldest-old [7]. In addition, social support status is a more important predictor of depression among older people from different cultures compared to the general population [8]. Hence, the symptoms and etiology of depression in late life may be more heterogeneous than in younger people [9]. Oldest-old adults, including centenarians, have constituted the fastest growing segments of the world population [10]. According to China’s General Program for Sustainable Development, China was projected to becoming a super-aged society by 2033 with a life expectancy of over 80 years, and having the largest population of the oldest-old across the globe [11]. However, due to the difficulties in taking a representative sample of the oldest-old and the shortage of psychiatrists, accurate depression screening among this population have not received enough attention [12].

The 15-item Geriatrics Depression Scale (GDS-15) has been widely used for depression screening and has been translated into multiple languages [13]. The GDS-15 was a simplified version of the 30-item long form GDS version developed by Sheik and Yesavage in 1986 [14]. Both ICD-10 criteria and DSM-IV criteria have shown that the GDS-15 was valid for measuring mild and major depression [15, 16]. In a systematic review, the pooled sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve of the GDS-15 were 79%, 77%, and 0.84 among older adults [9]. In China, however, there are no studies about the GDS-15’s properties in the oldest-old and centenarians; therefore, its efficacy in this population is unclear, and more psychometric evidence is needed. Since older people in an advanced age have cognitive difficulties, a simple yes/no response format in the GDS was more convenient than other measurement tools such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. Although the GDS-15 is more practical in clinical practice, the time required for answering all the questions is yet another burden for very old people, especially centenarians. Individual items regarding physical function and social activities are confounded with physical illness symptoms and may be burdensome for frail subjects [17]. It is still unclear whether all 15 items are suitable for Chinese oldest-old and centenarians, who tend to have declining physical abilities, low levels of literacy, and less social involvement. Re-evaluation and optimization of the GDS-15 seem necessary for depression screening in the oldest-old. The existing literature covered evidence about incidences and influencing factors of depression in later life [18, 19]. There were also evidence suggesting that the GDS-15 showed various validities among older adults [20, 21], while the psychometric properties of the GDS-15 among the oldest-old population (80+ years) is not yet clear.

The factor structure of the GDS is an important property when examining depression among samples of different ethnic backgrounds. However, as far as we are aware, the factor structure of the Chinese version GDS-15 among the oldest-old has not been well reported. A meta-analysis showed that conflicting GDS-15 structures (from 1 to 4 factors) were related to cross-cultural diversity in the expression of depressive symptoms among older people [13]. Furthermore, the older adults’ age, residence type, and social function may also contribute to the inconsistent results of the GDS. Several studies from the US and Europe countries obtained a two-factor structure regarding positive and negative emotions [22, 23]. While studies in Asia, including China, have shown that the GDS-15 had 3-4 dimensions [24,25,26]. Zhao et al. revealed that a three-factor model, including life satisfaction, general depressive affect, and withdrawal, fitted the GDS-15 best among Chinese community-dwelling older adults aged 60 to 99 years [24]. Lai et al. obtained a four-factor model including negative mood, positive mood, inferiority, and disinterested in older Chinese aged 55 years and above living in Canadian [27]. Previous studies have simplified the GDS-15 using multiple methodologies such as factor analysis, internal consistency, or item response theory (IRT) [28, 29]. As a result of the internally consistent reliability and expert consultation, Koenig et al. simplified the GDS to an 11-item version and found that it is sensitive and specific in inpatients [17]. Recently, Nahathai et al. used confirmatory factor analysis and IRT to eliminate 9 items from the original GDS-15 that might cause cultural bias and developed a new version that is comparable to the GDS-15 in its ability to detect depression [30]. A study conducted in the US showed that several items (dropped activities and interests, prefer to stay at home, and mind as clear as it used to be, etc.) in the GDS had poor consistency rate with clinical diagnosis among community older adults [31]. Another study from China showed that a 4-item GDS had equivalent sensitivity (57% vs. 60%), specificity (78% vs. 61%), and better accuracy (67% vs. 63%) in a mildly demented Chinese sample whose mean age was 80.87 years when comparing with the 15-item GDS [32]. These studies indicated that the accuracy of the GDS for screening depression in later life was associated with the conciseness of the scales, and even could be improved through removing some items that do not individually distinguish depression well. Ageing process is associated with function decline and social isolation, and it has been documented that identifying specific psychosocial symptoms from depression or other health conditions in the oldest-old was complicated [33]. One study from the United States showed significant age differences in the scores of specific items and dimensions of the GDS between centenarians and the younger old population [6]. Moreover, lifestyle, education, and social connections directly influence the respondent’s expression of depression [34]. Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study indicated that it might be difficult to distinguish depressive symptoms from physical symptoms caused by advanced age or fatigue, and the authors called for qualitative studies to address this issue [6]. Also, specific compound sentence patterns in the GDS may challenge older people’s understanding, and a previous Italian study reported additional difficulties among centenarians when answering dichotomous GDS questions due to the lower education and sensory impairment [35].

Despite the GDS-15’s properties being studied across several populations, most previous studies involved older people from Western countries [36] or younger old groups (aged 60 or above) [24, 26], while very few studies examined the oldest-old and centenarians with substantial sample sizes. Besides, existing studies relied on measurement methods to modify the GDS, and qualitative evidence on the applicability for each GDS items among the oldest-old is lacking. To address the gap of GDS-15’ utilities in the oldest-old population, we conducted this mixed-methods designed psychometric study to evaluate the reliability the reliability, structure validity, and measurement invariance of the scale using a large sample of Chinese oldest-old and centenarian persons. We also aim to identify the core depressive symptoms within this population and modify the GDS-15 by combining quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Participants and methods

Data source

The data for this study were collected from the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS), from June 2014 to December 2017. The CHCCS is a large cohort project designed to assess the physical function, mental health and social status of aging adults, as well as establish indicators for healthy aging [37]. According to the International Expert Committee on Population Aging and Longevity, Hainan Province has the highest percentage of centenarians (18.75/100 000) among all Chinese provinces [38]. Longevous persons live on this island their whole lives; therefore, Hainan province can provide a steady study sample. 1793 centenarians were initially recruited using a complete sampling according to the household registration data provided by the Civil Affairs Bureau method [37], and valid connections were established among 1473 centenarians. Inclusion criteria included: (1) 100 years or older by 1 June 2014; (2) volunteered to participate in the study and provided written informed consent; (3) was conscious and could cooperate to complete the interview and health examinations. 124 subjects who were unable to cooperate due to dementia or paralysis were excluded before the survey. 58 subjects who failed to meet the three-step age verification (Supplementary Figure 1), and 48 participants with more than 25% missing data were also excluded. In the second phase, the oldest-old participants (aged 80–99 years) were recruited as a control group in the second phase from 18 regions in Hainan. In total, 956 centenarians and 795 oldest olds were interviewed at home or health service centres by native nurses who were trained in interviewing older adults and able to speak the local dialect. We further excluded subjects (9 oldest-olds and 118 centenarians) who failed to answer two or more GDS questions. Considering the influence of missing values on the stability of factor analysis, participants with one missing GDS value were addressed using multiple imputation methods. The flowchart of sample selection process of this study was showed in Fig. 1.

Ethical statement

The ethics committee of the Hainan branch of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital approved the study protocol (301hn11201601). All participants or their guardians provided written informed consent before participating in the survey.

Measures

Depressive symptoms were measured using a Chinese version of the GDS [39]. The scale consists of 15 binary questions in which participants are asked to answer how they felt over the past week (1 = Yes, 0 = No). The total score of the GDS-15 is calculated as the sum of the 15 items, with a higher score indicating more depressive symptoms (possible range 0–15; observed range of 0–15). Participants who were illiterate or had cognitive impairment answered the questions with the help of investigators and their legal representatives. The 10-item Barthel Index was used to measure physical function [40]; subjects were considered exhibiting physical dependence if the total score was 90 points or less [41]. The 7-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) was used to assess subjective well-being level (observation range 0–35). Visual Analog Scale (VAS), a 20-cm vertical scale ranging from 0 to 100, was used to record self-rated health status.

Statistical analysis

We used mixed methods for the psychometric assessment of the GDS-15. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) and item-total correlation (ITC) were used to evaluate the internal reliability of the GDS-15. We conducted a standard expert consultation by inviting experts who have senior professional titles from the geriatric psychology field in China. Each expert was asked to rate the applicability of each item by a likert-5 score from “not applicable=1” to “very applicable=5”. The expert member panel should also select 3-10 items that can be deleted. As with previous studies that used content validity ratio to shorten scales, when an item in the GDS was selected by more than half of the experts, it was considered a candidate for deletion [42, 43]. Details of the consultation form and experts list were shown in Appendix 1 and 2. Third, Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were used to explore the optimal factor structure. Retained eigenvalues should meet the K1 criterion (≥ 1) and should be greater than the mean or the 95th percentile of the random samples in the parallel analysis (PA). Items with poor factor loading (<0.5) were considered for removal from the scale [44]. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with robust weighted least squares estimations were performed using Mplus (version 7.4) [45] to compare the fitness of competing GDS models. χ2/df, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and normed fit index (NFI) were used to evaluate the fitness. According to criteria recommended by statisticians, a model is considered good (or acceptable) if normed χ2/df ≤ 2 (3), RMSEA ≤ 0.06 (0.08), CFI ≥ 0.95 (0.90), and NFI ≥ 0.95 (0.90) [46]. Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were also used to evaluate the suitability of default models. Smaller AICs and BICs indicate better fitness for competitive models. Factorial invariance of the GDS across age, sex, residence, and education was tested by multi-group confirmatory factor analyses (MGCFA), which consisted of a series of nested confirmatory steps for parametric constraint models [47]. A non-significant △χ2 (P >0.05), a △CFI value<0.01, and a △RMSEA value<0.15 between alternative models indicate equivalent fitness of the factor structure across subgroups [48].

Results

Demographic characteristics

In total, 1624 individuals (94.30 ± 9.52 years) participated in this study. Among them 786 were oldest-olds (85.19 ± 4.30 years) and 838 were centenarians (102.48 ± 2.74 years). As Table 1 showed, most participants were female (71.3%), Han ethnic (89.4%), illiterate (84.1%), divorced or widowed (70.5%), lived at home (99.4%), and lived in cottages (72.7%). 92.2% of the participants had at least one closely connected relative, while only 42.0% had at least one closely connected friend. The prevalence of physical function dependence was 47.4%. The average summed GDS-15 score was 4.38 ± 3.02 (5.23 ± 3.24 for centenarians and 3.56 ± 2.50 for the oldest-old). Compared to the excluded participants who failed to respond enough GDS questions (n = 127), participants who were included in the final analysis were more likely to be younger, male, and lived in rural area (Supplementary Tables 1, Ps < 0.05).

Internal consistency

The α coefficient of the GDS-15 was 0.745 and increased after either item 9 or item 15 was deleted (Table 2). The item-total correlation coefficient ranged from 0.354 to 0.651 and mean of ITCs was 0.479.

Content validity

We obtained feedbacks from 19 geriatric psychologists on the applicability of each item. The average working lives of the experts was 24.3 years, and their advisory opinions were summarized in Table 2. Five items scored below 3.5 point for applicability, of which item 9 (1.94 ± 0.81), item 2 (2.39 ± 1.12), and item 15 (2.78 ± 1.06) were the lowest three. Among the 18 experts who provided suggestions on the removal of items, more than 9 experts chose to delete item 9 (17/18), item 2 (14/18), item 15 (12/18), item 8 (11/18), and item 10 (10/18).

Factor structure

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (0.801) and Bartelt’s sphere tests (χ2 = 1258.153, df=105, P < 0.001) supported the feasibility of the structure detection. In the first phase, we conducted parallel analysis for all 15 items and 4 factors were extracted. As Table 3 showed, the four factors (psychological perception; positive moods; negative moods and individual activities) accounted for 54.29% of the variance. Items with low reliability, poor factor loading, or recommendations for removal from more than 1/3 of the experts would be considered for removal. We also referred to the items that have been deleted in previous studies. Items 2, 9 and 15 had the lowest content validity, and items 9 and 15 impaired the overall consistency of the GDS. Besides, in an IRT study we have previously published, items 2 and 9 showed unacceptable guess parameter (>0.4) which indicated that the respondents might not provide truthful responses when answering these two questions [49]. Therefore, we deleted the above three items, and three factors were extracted from the remaining 12 items. In the GDS-12 model, two items (1 and 8) still showed poor factor loading (<0.5). Considering that more than 1/3 of the experts recommended deleting item 1 and 8, and they have also been suggested to deleted in some previous studies, we further deleted these two items and repeated the parallel analyses. Three factors explaining 60.86% of the variation were extracted and all the 10 items showed good or excellent loadings (>0.6). The three factors in the GDS-10 model were defined as psychological perception (items 2, 4, 11, and 14), positive moods (items 5, 7 and 13), and negative moods (items 6, 10 and 12). Scree plots of three GDS versions were shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The EFAs results remained consistent when excluding 43 participants with one missing GDS value (Supplementary Table 1).

Model fitness and factorial invariance

We conducted multi-group confirmatory factor analyses to compare the fitness of GDS models. We included four commonly used models as candidates from previous studies [24, 27, 28, 50, 51], and modified GDS versions with more than half of items removed were not included as most fitness indexes are closely related to item numbers in a scale. As summarized in Table 4, multiple indexes were used to compare the fitness of seven competing GDS models. The GDS-10 model (Model C) from the EFAs fitted the data better than the other models (χ2/df=1.94, CFI=0.976, RMSEA=0.048), and had an appropriate α coefficient and the highest ITC. Although the Model A, B, and F also had an acceptable CFI (> 0.9), the Model C showed smaller χ2/df, RMSEA, AIC, and BIC, and could be proposed as an optimal solution. The CFA model of the GDS-10 was shown in Supplementary Figure 3. We tested the factorial equivalence of the GDS-10 model using MGCFA. The configural invariance model (free parameters) was used as a basic model and three restrictive models (restrict loading, intercept, and residual sequentially) were tested in a stepwise manner. Results in Table 5 showed that the metric and scalar models had excellent fitness across age, sex, residence, and education (P >0.05, △CFI<0.01, △RMSEA<0.15) which indicated sufficient structural comparability between subgroups. According to the significance of △χ2, the measurement invariance of the residual restricted model was not well supported.

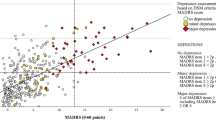

Concurrent validity

The mean ADL, SWLS, and VAS score was 83.63 ± 22.45, 21.98 ± 6.59, and 61.92 ± 15.26, respectively. The GDS-15 summed score was significantly negatively correlated with ADL (r =-0.310, P <0.001), SRH (r =-0.424, P <0.001) and SWLS (r =-0.273, P <0.001). Consistently, significant correlations were also found among the simplified GDS-10 with theoretically relevant health outcomes (r = -0.302 for ADL, -0.415 for SRH, -0.323 for SWLS).

Discussion

This study evaluated the internal consistency reliability, content validity, concurrent validity, and factor structure of the GDS-15 among Chinese oldest-old and centenarians. We also provided valuable suggestion for measuring depressive symptoms among this population and a simplified 10-item GDS version was proposed.

The acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.745) of the GDS-15 in our study was consistent with previous studies from China [27, 52] and other countries [28, 53]. We found that the overall α coefficient increased when deleting item 9 (Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out?) or item 15 (Do you think that most people are better off than you are?). Similarly, a study showed poor item-total correlation of item 2, 9, and 15 with the summed GDS-15 score among American community-based older adults [31]. Another study also reported that the GDS’s α coefficient increased when deleting the item 2 and 9 using a sample of older residents in Iran [28]. Unacceptable guessing parameters of items 2 (Have you given up many of your activities and hobbies?) and item 9 found in our published IRT study indicated that subjects without depressive symptoms would also respond to these two questions by guessing [49]. Previous IRT studies also showed that items 1, 2, 9, and 15 had significant differential item function between age and sex [54, 55]. In addition, items 2, 9, and 15 were the three most frequently deleted questions in our expert consultation approach due to lower content validity ratio. In the current study, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with physical function, life satisfaction, and self-reported health. Both the GDS-15 and the 10-item simplified version were found to have appropriate concurrent validity. The shorter version of the GDS showed potential predictive value for quality of life outcomes among older adults.

Longevous individuals in Hainan followed a specific lifestyle due to their advanced age and culture. Items 2 and 9 were related to the subject’s somatic ability, while older adults in Hainan had a higher prevalence of physical dependence (47.4%). Item 15 measures social communication, but the community-dwelling oldest-old and centenarians showed more social isolation compared with those living in cities or long-term care facilities. Most of the participants in the current study were divorced or widowed (70.5%), lived in rural areas (65.1%) and sparse cottages (72.7%), and had no closely connected friend (58.0%). Thus, the above three items might impair the overall reliability and we deleted them in the EFAs. Besides, item 9 was considered to exhibit a prominent cultural bias related with lifestyles of older persons, and several researches have recommended that this item be removed from the GDS [30]. In addition, since the original Chinese GDS-15 version was translated by researchers in Hong Kong, its wording may not be fully applicable to older people in mainland China. Also, the three items are compound statements rather than single sentences which may cause confusion due to the subjects’ high illiteracy rate (84.1%).

Item 1 and 8 were further deleted in consideration of insufficient factor loadings as well as expert consultation. As psychometricians suggested, satisfaction and depression could be considered as two independent latent traits, and item 1 is a general indicator of life satisfaction rather than a unique indicator of depression. Sheikh and colleagues also found that “satisfaction” did not load on any of the factors [56]. Item 8 (Do you ever feel like no one is helping you?) can be regarded an indicator of losing control of mental wellbeing as well as social avoidance. Although it might be a powerful indicator of depression from a clinical point of view, we need take the subjects’ living conditions into account. The community-based oldest-old in Hainan, especially centenarians, were more socially isolated than those living in nursing institutions, and item 8 might not be a typical depression indicator as well as item 15. Despite the potential instability of factor analyses, this psychometric method has been widely used in most validity studies. Tang and colleagues obtained a stable and comparable GDS models in both Chinese rural and urban samples by deleting four items with poor loadings [50]. In a few studies using EFA, poor loadings of these deleted items were also found. A study including Chinese immigrants aged 55+ years in Canada showed that factor loadings of item 1 and 2 were lower than 0.45 [27]. Poor loadings of item 8, 9 and 15 were also found in three community-based studies in Japan [25, 57] and New York [23]. Although the five deleted items have also been shown to be inappropriate in several previous studies, inconsistent results also existed. A study conducted by Daniel et al. showed good loadings in four factors for all the 15 items in urban Chinese older adults [26]. Unlike in Hainan, participants in Daniel’s study were younger, had higher education level, and living in crowded residential buildings. A well fitted 3-factor model with all loadings above 0.5 was also found in another study conducted among general older adults in Mainland China [24].

Studies assessing the construct structure of the GDS-15 have largely mixed findings which may be associated with culture, language, and sample heterogeneity [13, 27]. The four factors structure of the GDS-15 obtained in this study was found in studies from Japanese [57], Greek [58] and China [26]. However, two studies from Columbia and New York and have shown that the GDS-15 had a two factors structure including positive and negative moods [23, 59]. In contrast, studies in Asia generally found that the GDS-15 has 3-4 dimensions. Cultural diversities are one of the main reasons for these mixed results. The older persons in Western countries dare to directly express their emotional feeling to the people around them, while Chinese older people are more bashful. After five less valid items were deleted, the revised GDS-10 model showed better fitness than competing models (Table 4). Depression symptoms in Chinese oldest-old could be defined as a multidimensional concept including psychological perception (4 items), positive moods (3 items), and negative moods (3 items). Positive and negative moods can be considered two common depression dimensions [60], which have been examined in studies from Turkey [61], Korea [62], US [62], and China [27]. Although previous studies have confirmed the equivalence of the long-(30 items) and short-(15 items) form GDS for both sexes [24, 63], few studies have reported its equivalence across age groups, and especially for centenarians. Our MGCFA results confirmed the factorial invariance of the revised GDS-10 model, which indicated that the patterns of the three-factor model were equivalent across age, sex, education, and residence subgroups. For instance, despite concerns that demographic differences exist between the oldest-old and centenarians, the age invariance indicated that subjects across the two subgroups responded to the scale with the same underlying framework. Besides, the cross-educational equivalence of the GDS-10 supported its stable validity for illiterate oldest-old.

We matched several modified GDS versions with our GDS-10 and found that item combinations involved in different well performed simplified GDS versions was closely associated with the culture, age, and life condition of the older people. For example, items 1, 8, 9, 15 were deleted from four GDS versions (3-6 items) used in Turkey [61], whereas two 5-item GDS versions widely used in European and American contained 4 items that were deleted in our study [64, 65]. Similarly, when younger older people (>60 years) were screened for depression, some fatigue symptoms (such as item 2 and 9) were involved in a 12-item Chinese GDS version developed by Xie and colleagues using a Delphi method [66]. In Kathryn’s study [31], items 2 and 9 had poor accuracy for American older people (82.3 years) from nursing homes, while items 8 and 15 were of high accuracy. These results showed that physical function symptoms were not appropriate for the oldest-old while the applicability of social symptoms were associated with residence styles of the subject. In general, social activities related items were more often involved in settings conducted in long-term care services than in communities.

One strength of this study is the considerable sample size of oldest-old and centenarian adults from a non-Western country. Another strength is that we identified potential typical depression indicators in this special population using a mixed-methods approach of measurement proprieties and expert-based panel evaluation. Multiple aspects of the modified 10-item GDS version confirmed in the current study would provide quantitative and qualitative psychometric evidences for accurate depression screening among the oldest-old population. The study further suggested that in addition to emotional factors, physical function and social support status of the subjects should also be considered in depression screening, which is also applicable to other relevant studies. Several limitations should be noted. First, we were unable to conduct clinical depression diagnosis during the 3 years extensive survey due to the community-dwelling design of the CHCCS, thus sensitivity or specificity analyses were lacking. Further studies including standard clinical diagnostic procedures are warranted to test the accuracy of different GDS versions. However, 7 items in our simplified GDS-10 were included in the DSM-5 golden standard which might support the scale’s screening performance. Second, we did not include cognitive impairment as one of the exclusion criteria, as some previous studies have done [57, 67]. In the initial sample, we excluded participants were unable to establish a valid connection due to dementia or palsy (Fig. 1). Thus, we were able to ensure that subjects included in the final analysis could answer the GDS questions. In addition, the face-to-face interview conducted by a professional medical team including neurologists could reduce the difficulties in understanding and answering GDS questions. Third, although the sample of this study included a large number of community-based oldest-old adults, the subjects were all exclusively from one province, and generalization of the findings to older people from long-term care services should be done with caution. Fourth, since the option to add or replace items was not presented in the expert consultation form, we might have missed potentially valuable depression indictors when revising the GDS.

Conclusions

The GDS-15 has acceptable properties among Chinese oldest-old adults and centenarians. From the perspective of psychometric assessment, emotional symptoms are potential typical depression indicators for Chinese community-dwelling oldest-old, rather than those related to somatic function and social activity. The modified 10-item GDS with three factors could be proposed as a more practical and comprehensible instrument for depression screening among this population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Almeida OP. Prevention of depression in older age. Maturitas.2014; 79(2):136–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.03.005

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, et al. Age-and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life--systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):212–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033.

Jeon HS, Dunkle RE. Stress and Depression Among the Oldest-Old: A Longitudinal Analysis. Res Aging.2009; 31(6):661–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027509343541

Cullum S, Metcalfe C, Todd C, Brayne C. Does depression predict adverse outcomes for older medical inpatients? A prospective cohort study of individuals screened for a trial. Age Ageing.2008; 37(6):690–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn193

Wilkinson P, Ruane C, Tempest K. Depression in older adults. BMJ.2018; 363:k4922. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4922

Scheetz LT, Martin P, Poon LW. Do centenarians have higher levels of depression? Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Am Geriatr Soc.2012; 60(2):238–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03828.x

Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet.2005; 365(9475):1961–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66665-2

Hughes DC, DeMallie D, Blazer DG. Does age make a difference in the effects of physical health and social support on the outcome of a major depressive episode? Am J Psychiatry.1993; 150(5):728–33. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.5.728

Dennis M, Kadri A, Coffey J. Depression in older people in the general hospital: a systematic review of screening instruments. Age Ageing.2012; 41(2):148–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr169

Nations BU. Department of Economic and Social Affairs; World Population Ageing 2009. Population & Development Review. 2011;37:403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00421.x.

Yanan L, Binbin S, Zheng. X. Trends and Challenges for Population and Health During Population Aging — China, 2015-2050. China CDC Weekly.2021; 3(28):593–9.

Blazer DG. Psychiatry and the oldest old. Am J Psychiatry.2000; 157(12):1915–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1915

Kim G, DeCoster J, Huang CH, Bryant AN. A meta-analysis of the factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): the effects of language. Int Psychogeriatr.2013; 25(1):71–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610212001421

Sheikh. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol.1986; 5(1):165–73.

Wancata J, Alexandrowicz R, Marquart B, Weiss M, Friedrich F. The criterion validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2006; 114(6):398–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00888.x

Almeida OP, Almeida SA. Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: a study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(10):858–65 https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199910)14:10 < 858::aid-gps35>3.0.co;2-8.

Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Meador KG, Westlund R. A brief depression scale for use in the medically ill. Int J Psychiatry Med.1992; 22(2):183–95. https://doi.org/10.2190/m1f5-f40p-c4kd-ypa3

Castro-Costa E, Dewey M, Stewart R, Banerjee S, Huppert F, Mendonca-Lima C, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and syndromes in later life in ten European countries: the SHARE study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:393–401. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036772.

Areán PA, Reynolds CF, 3rd. The impact of psychosocial factors on late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry.2005; 58(4):277–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.037

Chaaya M, Sibai AM, Roueiheb ZE, Chemaitelly H, Chahine LM, Al-Amin H, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the short Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15). Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(3):571–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610208006741.

Castelo MS, Coelho-Filho JM, Carvalho AF, Lima JW, Noleto JC, Ribeiro KG, et al. Validity of the Brazilian version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) among primary care patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(1):109–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610209991219.

Mui AC. Geriatric Depression Scale as a community screening instrument for elderly Chinese immigrants. Int Psychogeriatr.1996; 8(3):445–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610296002803

Friedman B, Heisel MJ, Delavan RL. Psychometric Properties of the 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale in Functionally Impaired, Cognitively Intact, Community-Dwelling Elderly Primary Care Patients. J Am Geriatr Soc.2005; 53(9):1570–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53461.x

Zhao H, He J, Yi J, Yao S. Factor Structure and Measurement Invariance Across Gender Groups of the 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale Among Chinese Elders. Front Psychol.2019; 10:1360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01360

Imai H, Yamanaka G, Ishimoto Y, Kimura Y, Fukutomi E, Chen WL, et al. Factor structures of a Japanese version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its correlation with the quality of life and functional ability. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(2):460–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.015.

Lai D, Tong H, Zeng Q, Xu W. The factor structure of a Chinese Geriatric Depression Scale-SF: use with alone elderly Chinese in Shanghai, China. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2010; 25(5):503–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2369

Lai DW, Fung TS, Yuen CT. The factor structure of a Chinese version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med.2005; 35(2):137–48. https://doi.org/10.2190/crk0-cbn7-qeve-xwpg

Malakouti SK, Fatollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Salavati M, Zandi T. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GDS-15 in Iranian elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2006; 21(6):588–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1533

Amadori K, Herrmann E, Püllen RK. Comparison of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) and the GDS-4 during screening for depression in an in-patient geriatric patient group. J Am Geriatr Soc.2011; 59(1):171–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03212.x

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Kuntawong P. Evaluating hierarchical items of the geriatric depression scale through factor analysis and item response theory. Heliyon.2019; 5(8):e02300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02300

Adams KB. Do the GDS and the GDS-15 adequately capture the range of depressive symptoms among older residents in congregate housing? Int Psychogeriatr.2011; 23(6):950–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610210002425

Cheng ST, Chan AC. Comparative performance of long and short forms of the Geriatric Depression Scale in mildly demented Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2005; 20(12):1131–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1405

Dan, G., Blazer. Depression in Late Life: Review and Commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.2003; 58A:249–65.

Stek ML, Gussekloo J, Beekman AT, van Tilburg W, Westendorp RG. Prevalence, correlates and recognition of depression in the oldest old: the Leiden 85-plus study. J Affect Disord.2004; 78(3):193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00310-5

Segulin N, Deponte A. The evaluation of depression in the elderly: a modification of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Arch Gerontol Geriatr.2007; 44(2):105–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2006.04.002

Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY. Comparison of diagnostic performance of Two-Question Screen and 15 depression screening instruments for older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry.2017; 210(4):255–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.186932

He Y, Zhao Y, Yao Y, Yang S, Li J, Liu M, et al. Cohort Profile: The China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):694-5 h. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy017.

Wang L, Li Y, Li H, Holdaway J, Hao Z, Wang W, et al. Regional aging and longevity characteristics in China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:153–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.08.002.

Lee HCB, Chiu HFK, Kwok WY, Leung CM, Kwomg PK. Chinese elderly and the GDS short form: A preliminary study. Clin Gerontol.1993; 14:37–42.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J.1965; 14:61–5.

Van Hartingsveld F, Lucas C, Kwakkel G, Lindeboom R. Improved interpretation of stroke trial results using empirical Barthel item weights. Stroke.2006; 37(1):162–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000195176.50830.b6

Li CY, Al Snih S, Chen NW, Markides KS, Sodhi J, Ottenbacher KJ. Validation of the Modified Frailty Phenotype Measure in Older Mexican Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc.2019; 67(11):2393–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16104

Hatami O, Aghabagheri M, Kahdouei S, Nasiriani K. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). BMC Geriatr.2021; 21(1):383. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02337-0

BarbaraPrice. A First Course in Factor Analysis. Technometrics.1992; 35(4):1.

Muthén L MB: Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis With Latent Variables. Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh Edition); 2012.

Kline R, Kline RB, Kline R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Samuel DB, South SC, Griffin SA. Factorial invariance of the Five-Factor Model Rating Form across gender. Assessment.2015; 22(1):65–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114536772

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidiplinary Journal.2002; 9(2):233–55.

Zhang C, Zhang H, Zhao M, Liu D, Yao Y. Assessment of Geriatric Depression Scale’s Applicability in Longevous Persons based on Classical Test and Item Response Theory. J Affect Disord.2020; 274:610–6.

Tang D. Application of Short Form Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) In Chinese Elderly. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 2013; 21:402–5.

Schreiner AS, Morimoto T, Asano H. Depressive symptoms among poststroke patients in Japan: frequency distribution and factor structure of the GDS. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2001; 16(10):941–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.444

Boey, Weng K. The use of GDS-15 among the older adults in Beijing. Clin Gerontol.2000; 21(2):49–60.

Sugishita K, Sugishita M, Hemmi I, Asada T, Tanigawa T. A Validity and Reliability Study of the Japanese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS-15-J). Clin Gerontol.2017; 40(4):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2016.1199452

Haroz EE, Bolton P, Gross A, Chan KS, Michalopoulos L, Bass J. Depression symptoms across cultures: an IRT analysis of standard depression symptoms using data from eight countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2016; 51(7):981–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1218-3

Chiang KS, Green KE, Cox EO. Rasch analysis of the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form. Gerontologist.2009; 49(2):262–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp018

Sheikh, Yesavage JA, Brooks JO III, Friedman L, Gratzinger P, Hill RD, et al. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(1):23–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610291000480.

Onishi J, Suzuki Y, Umegaki H, Endo H, Kawamura T, Iguchi A. A comparison of depressive mood of older adults in a community, nursing homes, and a geriatric hospital: factor analysis of Geriatric Depression Scale. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol.2006; 19(1):26–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988705284725

Fountoulakis KN, Tsolaki M, Iacovides A, Yesavage J, O’Hara R, Kazis A, et al. The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece. Aging (Milano). 1999;11(6):367–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03339814.

Adalberto C-A, Yorjany UM, Tharim SM, Alí José Vergara P, Zuleima C. Internal consistency and exploratory factorial analysis of the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) in Cartagena (Colombia). Salud Uninorte.2008; 24(1):1–9.

Leung DY, Leung AY, Chi I. A psychometric evaluation of a negative mood scale in the MDS-HC using a large sample of community-dwelling Hong Kong Chinese older adults. Age Ageing.2012; 41(3):317–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr157

Dokuzlar O, Soysal P, Usarel C, Isik AT. The evaluation and design of a short depression screening tool in Turkish older adults. Int Psychogeriatr.2018; 30(10):1–8.

Jang Y, Small BJ, Haley WE. Cross-cultural comparability of the Geriatric Depression Scale: comparison between older Koreans and older Americans. Aging Ment Health.2001; 5(1):31–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860020020618

He J, Zhong X, Yao S. Factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale and measurement invariance across gender among Chinese elders. J Affect Disord.2018; 238:136–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.100

Hoyl MT, Alessi CA, Harker JO, Josephson KR, Pietruszka FM, Koelfgen M, et al. Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(7):873–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x.

Molloy DW, Standish TI, Dubois S, Cunje A. A short screen for depression: the AB Clinician Depression Screen (ABCDS). Int Psychogeriatr.2006; 18(3):481–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610205003078

Xie Z, Lv X, Hu Y, Ma W, Xie H, Lin K, et al. Development and validation of the geriatric depression inventory in Chinese culture. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(9):1505–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215000162.

Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res.2004; 57(3):297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.01.004

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff of the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study for their joint efforts and cooperation. We also appreciate the 16 external experts for their professional suggestions on the applicability and modification of the Chinese version of GDS-15. Those experts are from Beijing Hospital (Prof. Xiasheng Hu, Prof. Ping Zeng, Prof. Kai Wu, and Prof. Qing He), Chinese PLA General Hospital (Prof. Hengge Xie, Prof. Hong Cui, and Prof. Jing Lv), Beijing Normal University (Prof. Huamao Hu and Prof. Dahua Wang), Institute of Psychology in Chinese Academy of Sciences (Prof. Buxin Han, Prof. Xinyi Zhu, and Prof. Zhiwei Zheng), Peking University Sixth Hospital (Prof. Huali Wang), Xiangya Nursing School of Central South University (Prof. Hui Zeng), Guangzhou Medical University (Prof. Zhizhong Wang), Karolinska Institutet (Dr. Xin Li).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China [grant number: 2018YFC2000400], Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers: 81903392, 81941021], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number: 3332021077]. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and independent from the funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CZ and YY: conception and design, analyzing and interpreting data, writing manuscript; CZ, ZY, and YY: interpreting data, drafting, and editing manuscript; ZH, ZM, CC, LD, and LZ: drafting and editing manuscript; ZY and YY: supervising study and obtaining funding. All authors approval of final version before publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each participant or their guardians provided written informed consent to be included in the study. The ethics committee of the Hainan branch of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (Sanya, Hainan) approved the study protocol (301hn11201601). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

YY is an editorial board member of BMC Geriatrics. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Three-steps age validation process of centenarians in CHCCS. Figure S2. Scree plots of the threeGeriatrics Depression Scale versions in parallel analysis. Eigenvalues >1and greater than the corresponding eigenvalue from the random data (either theaverage or the 95th percentile) were retained. Figure S3. Three-factor GDS-10 model for Chinese oldest-old andcentenarians. Factor 1: psychologicalperception (item 3, 4, 11 and 14); Factor 2: positive moods (item 5, 7 and 13);Factor 3: negative moods (item 6, 10 and 12). Table S1. Demographic characteristics of the finally analysed sample and excludedparticipants. Table S2. Factors analyses of threeGDS versions among 1581 participants without missing value. Appendix 1. Consultation form of the applicabilityof the GDS-15. Appendix 2. Information of 19 experts inthe consultation

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Zhang, H., Zhao, M. et al. Psychometric properties and modification of the 15-item geriatric depression scale among Chinese oldest-old and centenarians: a mixed-methods study. BMC Geriatr 22, 144 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02833-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02833-x