Abstract

Background

According to some studies, interventions can prevent or delay frailty, but their effect in preventing adverse outcomes in frail community-dwelling older people is unclear. The aim is to investigate the effect of an intervention on adverse outcomes in frail older adults.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis of Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Social Sciences Citation Index. Randomized controlled studies that aimed to treat frail community-dwelling older adults, were included. The outcomes were mortality, hospitalization, formal health costs, accidental falls, and institutionalization. Several sub-analyses were performed (duration of intervention, average age, dimension, recruitment).

Results

Twenty-five articles (16 original studies) were included. Six types of interventions were found. The pooled odds ratios (OR) for mortality when allocated in the experimental group were 0.99 [95% CI: 0.79, 1.25] for case management and 0.78 [95% CI: 0.41, 1.45] for provision information intervention. For institutionalization, the pooled OR with case management was 0.92 [95% CI: 0.63, 1.32], and the pooled OR for information provision intervention was 1.53 [95% CI: 0.64, 3.65]. The pooled OR for hospitalization when allocated in the experimental group was 1.13 [95% CI: 0.95, 1.35] for case management. Further sub-analyses did not yield any significant findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis does not provide sufficient scientific evidence that interventions by frail older adults can be protective against the included adverse outcomes. A sub-analysis for some variables yielded no significant effects, although some findings suggested a decrease in adverse outcomes.

Trial registration

Prospero registration CRD42016035429.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The population in the European Union is aging rapidly [1], and studies show that 30% of this population will be over age 65 by 2060 [1]. Therefore, the number of frail older adults with a high need for care and support will increase, and resource optimization is necessary [2, 3]. The literature describes two approaches to frailty [4,5,6]. The first, often designated as physical frailty, emphasizes frailty as a biological/medical concept, defined as “a medical syndrome with multiple causes and contributors that is characterized by diminished strength, endurance, and reduced physiologic function that increases an individual’s vulnerability for developing increased dependency and/or death” [7]. The second approach investigates frailty in a multidimensional way. In addition to strength or endurance, this perspective emphasizes cognitive, social, and psychological factors as defined by Gobbens et al.: “Frailty is a dynamic state affecting an individual who experiences losses in one or more domains of human functioning (physical, psychological, social), which is caused by the influence of a range of variables and which increases the risk of adverse outcomes” [8].

Many studies suggest that frailty is associated with adverse outcomes including mortality, institutionalization, hospitalization, and accidental falls [7, 9,10,11,12]. Some authors assume that early detection and intervention are important to prevent or delay frailty, improve quality of life, and reduce costs of care [7, 13]. Nevertheless, it is unclear if interventions in frail community-dwelling older adults can be protective against adverse frailty outcomes [14,15,16,17,18].

This systematic literature review and meta-analysis examines the following three questions: Which interventions are applied to protect frail community-dwelling older adults against adverse outcomes? What effect do interventions have on frail community-dwelling older adults in terms of mortality, hospitalization, formal health costs, accidental falls, and institutionalization? Finally, how do age, study duration, and the multi- versus unidimensional approaches of frailty and recruitment influence the effect of an intervention?

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed. Four electronic databases were consulted: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library (CL), and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI). The SSCI was consulted to assure that articles with a multidimensional approach to frailty would be found. The recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews for Interventions 5.1.0 were used [19], and the protocol was registered (Prospero registration CRD42016035429).

Search strategy

The search strategy used four key terms: aged, frail elderly, independent living, and randomized controlled trial (RCT). The final search strategy was developed with the help of a librarian (Additional file 1: Data S1). The search for articles was carried out for the first time in September 2015 and the second time on June 17, 2016. The references for the selected articles were screened for other potentially relevant publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Within the scope of this study, the population in the included articles had to be 60 years or older, diagnosed as frail, and community-dwelling. Concerning the intervention and methodology, all studies had to be RCTs, frailty had to have been operationalized (regardless of the frailty operationalization), all types of intervention were allowed, there was no recruitment after hospital discharge (inpatient and outpatient), and the intervention must have been compared with care as usual. The studies needed to have one or more of the following outcomes: mortality, institutionalization, hospitalization, formal health costs, and accidental falls. Pilot studies and studies not written in English, French, German, or Dutch were excluded.

Selection of studies

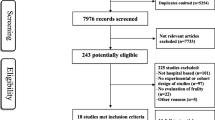

Retrieval and selection of studies were performed in a stepwise way. After duplicate records were removed, titles and abstracts were screened. Two reviewers assessed a sample of 12% (MVDE and DD). If their agreement reached 95%, the first author continued the inclusion process alone. In the next step, two researchers (MVDE and DD) independently read the full text of the selected articles for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases of doubt or disagreement, a third researcher (BV) was asked to judge.

Critical appraisal

Two independent researchers (DL and BF) assessed the quality of each article with the Cochrane risk of bias tool [19]. An evaluation was made in seven areas (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other bias). If an article met two or fewer criteria, it was defined as low quality; meeting three or four criteria was defined as medium quality; and if it met more than four criteria, it was considered a high-quality paper.

Data extraction

The first author preformed the data-extraction by preparing an excel sheet including all the necessary data to answer the research questions like average age of a study, number of participants. Subsequently two researchers (DL and BF) controlled the accuracy of the data-extraction. Information concerning average age, percentage of male participants, type of intervention, operationalization of frailty, and method of recruitment of participants (e.g. participants could be recruited through census records, a service center or a care center, etc.) were subsequently collected and categorized (Additional file 2: Text S1). Frailty was defined unidimensionally if it included solely biological aspects (i.e., nutritional status, physical activity, mobility, strength, and energy). Frailty was defined multidimensionally if it also included variables such as cognition, mood, and social relations/social support [20].

Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Review Manager 5.3 [21]. For the outcomes of mortality, institutionalization (residential home/nursing home/long-term care facility), and hospitalization (inpatients), the odds ratio (OR) was calculated for every intervention; for the outcome of accidental falls, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) was presented; for formal health costs a percentage was calculated, the sum of all the presented formal health costs in the intervention group (IG) was divided by the sum of all the presented formal health costs in the control group (CG). Raw data were used for the variables mortality, institutionalization and hospitalization, for accidental falls the IRR scores were used reported in the articles. If data were unclear the first author was contacted If possible, a pooled meta-analysis was executed to measure the odds ratio. A random effect model was applied because one can assume no common effect size exist, the study population may differ from each other in ways that could affect the treatment effect (e.g., differences in the average age of the study population). Differences among included studies were assessed and described in terms of heterogeneity. A sub-analysis was performed for duration of intervention, a multi- versus unidimensional approach to frailty, average age, recruitment method of the participants, and studies with a moderate or high quality. A sub-analysis also was performed for studies that used the Fried criteria or the Frailty Index. Funnel plots were inspected, and studies with multiple research arms were analyzed separately.

Results

The details of the search process are presented (Additional file 3: Figure S1). After the databases were searched, 25 articles were included for review representing 16 original studies. Duplicate data were excluded. All included papers are listed in Table 1 with study characteristics. The 16 original studies involved the following: nine with a case management intervention [2, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], three with information provision interventions [38,39,40,41], one with physical intervention [42], one with psychosocial intervention [43], one with a pharmaceutical intervention [44], and one with a technological intervention [45]. Six articles approached frailty in an unidimensional way [2, 22,23,24,25,26, 37, 42, 44, 45], nine articles approached frailty in a multidimensional way [27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38,39,40,41, 43], and in one article the approach of frailty was unclear [28]. Two papers were of low quality (≤2) [39, 45]. For the interventions of case management and information provision, pooled meta-analyses were performed. For case management, sub-analyses also were performed.

The effects of an intervention

The effects of an intervention in the original studies are listed in Table 2. Two results were significantly better in the IG in comparison with the CG. In Hall et al. [29], the intervention of case management resulted in a lower institutionalization, with an OR of 0.32 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.12, 0.87]. Perttila et al. performed a study with a physical intervention, this resulted in a lower number of accidental falls with an IRR of 0.43 [42]. Four articles also offered an economic evaluation of the intervention, with one involving an information provision intervention showing a decrease in formal health costs in the IG of 11.84% in comparison with the CG [39].

For case management and information provision intervention, a pooled meta-analysis was performed (Table 3). The pooled ORs for mortality when allocated in the experimental group were 0.99 [95% CI: 0.79, 1.25] for case management and 0.78 [95% CI: 0.41, 1.45] for provision information intervention. The mortality ORs for the other interventions (pharmaceutical, 3.19 [95% CI: 0.13, 81.25]; psychosocial, 1.20 [95% CI: 0.41, 3.49]; technological, 7.48 [95% CI: 0.35, 157.76]) were greater than one.

For institutionalization, the pooled OR with case management was 0.92 [95% CI: 0.63, 1.32], and the pooled OR for information provision was 1.53 [95% CI: 0.64, 3.65]; they were not significant. The pooled OR for hospitalization when allocated in the experimental group was 1.13 [95% CI: 0.95, 1.35] for case management. The funnel plots, statistical heterogeneity and forest plots can be found in the appendix (Additional file 4: Figure S2: Funnel plot and Forest plot).

Sub-analysis

The influence of duration of intervention, average age, multi- versus unidimensional approach to frailty, and recruitment on the effect of an intervention was explored. Various sub-analyses were performed but with no significant results (Table 4). For the variable of age in the category ≤80, the risk for an adverse outcome was lower. Several methods to operationalize frailty were allowed, and a sub-analysis was performed. When frailty was operationalized with the Fried criteria [5] or the Frailty Index [6], the OR for mortality was 1.12 [95% CI: 0.52, 2.41].

Two papers had a low quality (≤2) (Additional file 5: Figure S3: critical appraisal) [39, 45]. For information provision, a sub-analysis was performed, and the pooled OR for mortality increased from 0.76 to 0.94 [95% CI: 0.42, 2.11]. For institutionalization, the pooled OR decreased from 1.53 to 1.35 [95% CI: 0.34, 5.29] (Additional file 4: Figure S2: Funnel plot and Forest Plot).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of interventions to prevent adverse outcomes in frail community-dwelling older people. This systematic review and meta-analysis does not provide sufficient scientific evidence that interventions can be protective against the included adverse outcomes. A sub-analysis for some variables (duration of intervention, average age, dimension, recruitment) yielded no significant effects, although some findings suggested a decrease in adverse outcomes.

The results of this systematic review are in line with previous studies: the effect is unclear and inconsistent. In a systematic review, You et al. examined the effect of case management on mortality/survival days, and two out of seven articles reported a significant result [16]. Also, Hallberg and Kristerisson found in their systematic review that the effect of an intervention differed among studies: some found no effect on hospital admission, length of stay, or number of hospital days whereas others reported fewer hospital admissions and/or shorter lengths of stay [46]. Mayo-Wilson et al. concluded in their systematic review that home visiting is not consistently associated with a higher risk of mortality [47].

A pooled meta-analysis should lead to more significant and consistent results, yet this analysis did not. However, the literature provides evidence that a pooled meta-analysis could produce significant findings. For example, Elkan et al. reported that mortality and institutionalization are significantly lower after a home-based support intervention for frail older adults in comparison with a control group [48]. Thomas et al. concluded that a physical intervention reduces mortality in older community-dwelling adults, but the inclusion criteria did vary among the included studies in these two analyses, which may explain the differences in outcome. Elkan et al. included non-randomized studies and studies with older adults recently discharged from the hospital [48] whereas the older adults in Thomas et al. are not defined as frail [49].

Remarkably, the data in the current work show that the odds of being hospitalized are higher in the intervention group than in the control group (Table 2). Berglund et al. reported in their RCT that after the intervention, participants in the experimental group were much more aware of whom to contact with questions about care and services [50]. This effect could explain why the odds of being hospitalized were higher in the intervention group than in the control group and is a likely reason why the results for the outcome of formal health cost in the experimental group were not significantly lower than in the control group.

The studies in the current analysis showed heterogeneity for average age, duration, etc., which could explain the inconsistency in the results [51]. A sub-analysis should lead to significant and consistent results. For example, Stuck et al. concluded that a preventive program reduces mortality in a younger study population (mean age < 80 years) but not in older populations [52]. However, in this study, a sub-analysis for the variable average age ≤ 80 years (Table 3) was not significant, and neither were the results of other sub-analyses. Our findings confirm Elkan et al.: population type, duration, and age have no significant effect on mortality and institutionalization [48].

Considerations for future research

A plausible reason for the lack of evidence is the heterogeneity within studies. Within studies, the contextual factors of the population in the experimental group was heterogeneous, with differences in age, educational level, morbidities, and context, etc. If frailty is operationalized with a multidimensional approach, however, the question that arises is: ‘which dimensions were problematic?’ Also the local setting within studies was heterogeneous, Van Leeuwen et al. used two regions, and Kono et al. and Perttila et al. used three regions [36, 39, 40, 42]. It is plausible that an intervention within a subgroup is effective. Analyzing the results of an experiment on an aggregated level might lead to an ecological fallacy [53].

Future research should not solely focus on the effect of an intervention but also address the question: why did interventions work when they did or why not, for who did they work and what contextual factors triggered the mechanisms required to make them work. This is described by Pawson and Tilley in ‘realistic evaluation’ (1997). They suggest that a realistic evaluation approach might provide a better understanding of the effect of an intervention [54]. This approach is a theory-driven method that not only addresses the outcome of an intervention, but also why interventions worked, when they worked or for who they worked [54].

A consensus about the concept of frailty is necessary for future research and would enable comparison, evaluation, and replication of interventional studies. Some authors have made valuable efforts toward reaching a consensus [7]; for example, ‘The White Book on Frailty’ has delivered an important contribution to this understanding [13].

Several other explanations are possible for the current results. The selected population may have been detected too late and already have been too frail [13, 15]. In addition, societal trends, such as changes in structure and function of families, might have aggravated the incidence or severity of frailty and complicated its effective management [13]. A lack of mindfulness for these societal trends also may be an explanation for the non-significant results. Several authors have discussed the difficulties of implementing the intervention [32, 34]. As a last consideration, future research making an economic evaluation must consider the extra awareness of services that older adults gain through an intervention [50].

Strengths and limitations

Previous systematic reviews have focused on the effect of one intervention in comparison with care as usual [55,56,57,58]. A strength of the current analysis is the overview of interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults in the context of several adverse outcomes. A second strength is that only RCTs were included whereas several other systematic reviews have also included non-RCTs [46, 51]. In this analysis, differences among studies were assessed (heterogeneity) in terms of duration of the intervention, average participant age, dimensional approach to frailty, recruitment of participants, and frailty operationalization, constituting a third strength. A fourth strength is that three of the five outcome measures – mortality, institutionalization, and hospitalization – are collected primarily through registers and can be seen as objective data, which decreases the risk for bias [2].

The analysis also has some weaknesses, so that the results should be interpreted with caution. A first weakness is the small number of original studies, which led to meta-analyses only for case management and information provision and reduced the reliability of the results. One reason for the small numbers of included publications is the lack of operationalization of ‘frailty’ in studies. An absence of an operationalization of frailty is also a feature in other studies [15, 17]. Other reasons for exclusion were a lack of usual care, no relevant outcomes, and the recruitment of non-community-dwelling participants. A second weakness is the concept of frailty. Several methods are used to operationalize frailty, and some may not be accurate enough to recruit frail older adults, making study comparison and evaluation difficult [56]. A third weakness is that several concepts, such as case management, information provision, institutionalization, and formal health costs, have different operationalizations, leading to heterogeneity among studies. In the current analysis, mortality, institutionalization, accidental falls, formal health costs, and hospitalization were used because they are often cited as adverse outcomes. Other outcomes not included in this systematic review include functional status, physical performances, quality of life, mastery, disability, etc. [14], which can be seen as a weakness. These outcomes are not included because of the different methods to operationalize these concepts.

Conclusion

The number of frail older adults with a high need of care and support is increasing. According to some studies, interventions can prevent or delay frailty, but their effect in preventing adverse outcomes in frail community-dwelling older people is unclear. The aim of this article was to investigate if interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults can be protective against adverse outcomes. This systematic review and meta-analysis does not provide sufficient scientific evidence that supports this assumption, even though some results suggest a decrease in adverse outcomes.

Future research must consider that the research population of older adults is very heterogeneous, also within studies. A good breakdown of all of these characteristics is necessary, and sub-analyses might avoid ecological fallacies. Each patient’s specific needs and how to deliver these services are probably essential for the effectiveness of an intervention. New methods/approaches, for example the realist approach might provide a better understanding of the effect of an intervention. Future research must also consider new societal trends, implementation problems, and heightened awareness about services that may influence the results.

Abbreviations

- CG:

-

Control group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CL:

-

The Cochrane Library

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OS:

-

Original studies

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SSCI:

-

Social Sciences Citation Index

References

Eurostat. Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations A statistical portrait of the European Union 2012. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2012.

Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Kurrle SE, et al. Economic evaluation of a multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention versus usual care to reduce frailty in frail older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc [Internet]. 2015;16(1):41–8.

European Social Network Services for older people in Europe: Facts and figures about long term care services in Europe. 2008.

Lally F, Crome P. Understanding frailty. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(975):16–20.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):146–56.

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323–36.

Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7.

Gobbens RJJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JMGA. In search of an integral conceptual definition of frailty: opinions of experts. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(5):338–43.

Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of future falls among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1027–33.

Kelaiditi E, Andrieu S, Cantet C, et al. Frailty index and incident mortality, hospitalization, and institutionalization in Alzheimer's disease: data from the ICTUS study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(4):543–8.

Rockwood K, Fox RA, Stolee P, et al. Frailty in elderly people: an evolving concept. CMAJ. 1994;150(4):489.

Mosquera C, Spaniolas K, Fitzgerald TL. Impact of frailty on surgical outcomes: the right patient for the right procedure. Surgery. 2016;160(2):272–80.

Vellas B. White book on frailty. 2016. Available at: https://www.jpn-geriat-soc.or.jp/gakujutsu/pdf/whitebook.pdf. Accessed 26 Oct 2016.

Daniels R, van Rossum E, de Witte L, et al. Interventions to prevent disability in frail community-dwelling elderly: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–8.

Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP, et al. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:1–19.

You EC, Dunt D, Doyle C, Hsueh A. Effects of case management in community aged care on client and carer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials and comparative observational studies. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2012;12:1–14.

Clegg AP, Barber S, Young JB, et al. Do home-based exercise interventions improve outcomes for frail older people? findings from a systematic review Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;22(1):66–78.

Chin APMJ, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen I, van Mechelen W. The functional effects of physical exercise training in frail older people : a systematic review. Sports Med. 2008;38(9):781–93.

Collaboration TC. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of. Interventions. 2011.

de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, et al. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104–14.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre TCC; 2014.

Aggar C, Ronaldson S, Cameron ID. Reactions to caregiving during an intervention targeting frailty in community living older people. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:1–11.

Cameron ID, Fairhall N, Langron C, et al. A multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:1–10.

De Vriendt P, Peersman W, Florus A, et al. Improving health related quality of life and independence in community dwelling frail older adults through a client-centred and activity-oriented program. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Health & Aging [Internet]. 2016;20(1):35–40.

Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Effect of a multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention on risk factors for falls and fall rate in frail older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing [Internet]. 2014;43(5):616–22.

Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Kurrle SE, et al. Effect of a multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention on mobility-related disability in frail older people: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med [Internet]. 2012;10:1–13.

Favela J, Castro LA, Franco-Marina F, Sánchez-García S, Juárez-Cedillo T, Bermudez CE, et al. Nurse home visits with or without alert buttons versus usual care in the frail elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:85–95.

Hall N, De Beck P, Johnson D, et al. Randomized trial of a health promotion program for frail elders. Can J Aging. 1992;11(1):72–91.

Hoogendijk EO, van der Horst HE, van de Ven PM, et al. Effectiveness of a geriatric care model for frail older adults in primary care: results from a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;28:43–51.

Kehusmaa S, Autti-Rämö I, Valaste M, et al. Economic evaluation of a geriatric rehabilitation programme: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehab Med [Internet]. 2010;42(10):949–55.

Metzelthin SF, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, et al. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary primary care approach to reduce disability in community dwelling frail older people: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:1–12.

Metzelthin SF, Van Rossum E, De Witte LP, et al. Frail elderly people living at home; effects of an interdisciplinary primary care programme. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2014;158(17).

Metzelthin SF, van Rossum E, Hendriks MR, et al. Reducing disability in community-dwelling frail older people: cost-effectiveness study alongside a cluster randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2015;44(3):390–6.

van Hout HP, Jansen AP, van Marwijk HW, et al. Prevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(7):734–42.

Ollonqvist K, Aaltonen T, Karppi SL, et al. Network-based rehabilitation increases formal support of frail elderly home-dwelling persons in Finland: randomised controlled trial. Health Soc Care Community [Internet]. 2008;16(2):115–25.

Van Leeuwen KM, Bosmans JE, Jansen AP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a chronic care model for frail older adults in primary care: economic evaluation alongside a stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2494–504.

Williams ME, Williams TF, Zimmer JG, et al. How does the team approach to outpatient geriatric evaluation compare with traditional care: a report of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 1987;35(12):1071–8.

Kono A, Kanaya Y, Fujita T, et al. Effects of a preventive home visit program in ambulatory frail older people: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2012;67(3):302–9.

Kono A, Kanaya Y, Tsumura C, Rubenstein LZ. Effects of preventive home visits on health care costs for ambulatory frail elders: a randomized controlled trial. Aging clin exp res [Internet]. 2013;25(5):575–81.

Kono A, Izumi K, Yoshiyuki N, et al. Effects of an updated preventive home visit program based on a systematic structured assessment of care needs for ambulatory frail older adults in Japan: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016:1–7.

Monteserin R, Brotons C, Moral I, et al. Effectiveness of a geriatric intervention in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Fam Pract. 2010;27(3):239–45.

Perttila NM, Ohman H, Strandberg TE, et al. Severity of frailty and the outcome of exercise intervention among participants with Alzheimer disease: a sub-group analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;7(2):117–21.

Dorresteijn TA, Zijlstra GA, Ambergen AW, et al. Effectiveness of a home-based cognitive behavioral program to manage concerns about falls in community-dwelling, frail older people: results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:1–11.

Kim H, Suzuki T, Kim M, et al. Effects of exercise and milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) supplementation on body composition, physical function, and hematological parameters in community-dwelling frail Japanese women: a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled, follow-up trial. PloS one [Internet]. 2015;10(2):1–20.

Upatising B, Hanson GJ, Kim YL, et al. Effects of home telemonitoring on transitions between frailty states and death for older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int j Gen Med [Internet]. 2013;6:145–51.

Hallberg IR, Kristerisson J. Preventive home care of frail older people: a review of recent case management studies. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(6B):112–20.

Mayo-Wilson E, Grant S, Burton J, et al. Preventive home visits for mortality, morbidity, and institutionalization in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89257.

Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):719–24.

Thomas S, Mackintosh S, Halbert J. Does the 'Otago exercise programme' reduce mortality and falls in older adults?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39(6):681–7.

Berglund H, Wilhelmson K, Blomberg S, et al. Older people's views of quality of care: a randomised controlled study of continuum of care. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(19–20):2934–44.

Low LF, Yap M, Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:1–15.

Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, et al. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1022–8.

Billiet J, Waege H. Een samenleving onderzocht: methoden van sociaal-wetenschappelijk onderzoek. 2005.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. Monograph prepared for British Cabinet Office 2004.

De Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, et al. Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1–16.

Gustafsson S, Edberg A-K, Johansson B, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Multi-component health promotion and disease prevention for community-dwelling frail elderly persons: a systematic review. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(4):315–29.

Barlow J, Singh D, Bayer S, Curry R. A systematic review of the benefits of home telecare for frail elderly people and those with long-term conditions. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(4):172–9.

Eklund K, Wilhelmson K. Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(5):447–58.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michels Marleen (KU Leuven), who helped with the development of the search strategy. The D-SCOPE consortium is an international research consortium and is composed of researchers from Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium (dr. A.-S. Smetcoren, dr. S. Dury, prof. dr. L. De Donder, prof. dr. N. De Witte, prof. dr. E Dierickx, D. Lambotte, B. Fret, D. Duppen, prof. dr. M. Kardol, prof.dr. D. Verté); College University Ghent, Belgium (L. Hoeyberghs, prof. dr. N. De Witte); University Antwerpen, Belgium (dr. E De Roeck, prof. dr. S Engelborghs, prof. dr. P. P. Dedeyn); KU Leuven, Belgium (M. Van der Elst, prof. dr. B. Schoenmakers, prof. dr. J. De Lepeleire) and Maastricht University, The Netherlands (A. Van der Vorst, dr. G.A.R. Zijlstra, prof. dr. G.I.J.M Kempen, prof. dr. J.M.G.A Schols) .

Funding

Funding was provided by the instituut voor Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie (IWT). IWT-project number: IWT-140027 with the title “D-SCOPE: Detection - Support and Care of Older People in their Environment”. The instituut voor Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie (IWT) had no role in study design, data collection, data-analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Availability of data and materials

All the data were retrieved from published RCTs. The included articles can be found in Table 1 and the exact references can be found in the list of references. All the relevant data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [or in the additional information files]. The Funnel plots and Forest plots from the sub-analyses are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MVDE: study concept, data collection and data-analysis, drafting the manuscript. BS: study concept data-analysis, drafting manuscript, DD: data collection, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. DL: data extraction, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. BF: data extraction, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. BV: data collection, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. JDL: study concept, data-analysis, drafting the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and because no human subjects were involved; no informed consent was necessary and no ethics committee was involved.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Data S1. Search strategy (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Text S1. Extra information operationalization and categorization of Variables. (DOCX 19 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S1. Flow chart (PDF 188 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S2. Funnel plot and Forest plot (PDF 257 kb)

Additional file 5:

Figure S3. Critical appraisal (PDF 187 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Van der Elst, M., Schoenmakers, B., Duppen, D. et al. Interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults have no significant effect on adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 18, 249 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0936-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0936-7