Abstract

Background

Mounting evidence has suggested that plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is a candidate for increased risk of diabetic retinopathy. Studies have reported that insertion/deletion polymorphism in the PAI-1 gene may influence the risk of this disease. To comprehensively address this issue, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the association of PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Data were retrieved in a systematic manner and analyzed using Review Manager and STATA Statistical Software. Crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the strength of associations.

Results

Nine studies with 1, 217 cases and 1, 459 controls were included. Allelic and genotypic comparisons between cases and controls were evaluated. Overall analysis suggests a marginal association of the 4G/5G polymorphism with diabetic retinopathy (for 4G versus 5G: OR 1.13, 95%CI 1.01 to 1.26; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.30, 95%CI 1.04 to 1.64; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: OR 1.26, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.52). In subgroup analysis by ethnicity, we found an association among the Caucasian population (for 4G versus 5G: OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.30; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.33, 95%CI 1.02 to 1.74; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: OR 1.41, 95%CI 1.13 to 1.77). When stratified by the average duration of diabetes, patients with diabetes histories longer than 10 years have an elevated susceptibility to diabetic retinopathy than those with shorter histories (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.47, 95%CI 1.08 to 2.00). We also detected a higher risk in hospital-based studies (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G+4G/5G: OR 1.27, 95%CI 1.02 to 1.57).

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis suggested that 4G/5G polymorphism in the PAI-1 gene potentially increased the risk of diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes and showed a discrepancy in different ethnicities. A higher susceptibility in patients with longer duration of diabetes (more than 10 years) indicated a gene-environment interaction in determining the risk of diabetic retinopathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), the leading cause of blindness in the working population, is associated with a strong genetic predisposition, highlighted by the familial clustering of DR [1, 2]. Several gene polymorphisms are associated with DR, such as in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene, endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene, manganese superoxide dismutase gene, vascular endothelial growth factor gene, receptor for advanced glycation end products gene, aldose reductase 2 gene and P-selectin gene, among others [3–9]. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), the most important in vivo inhibitor of plasminogen activation, has also been implicated in DR. In addition to being involved in tissue repair and remodeling, PAI-1 plays a critical role in the regulation of intravascular fibrinolysis. In patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), impaired fibrinolysis is involved in the pathogenesis of DR [10]. Increased PAI-1 expression has been associated with matrix accumulation [11] and the development of basement membrane thickening and pericyte loss, which are regarded as the earliest retinal pathohistological changes in DR in transgenic mice [10, 12]. PAI-1 activity, which is affected by PAI-1 gene polymorphisms and metabolic determinants, is also elevated in DR [13]. Compared with other PAI-1 variants, the most significant variation in PAI-1 expression resides in a common single-base-pair guanine insertion/deletion polymorphism (4G/5G) within the promoter region of the PAI-1 gene at nucleotide position -675 [11, 14]. Unlike the 5G allele that binds a transcription repressor protein, resulting in low PAI-1 expression, the 4G allele does not bind a transcription repressor, thus conferring a 'high PAI-1 expressor' nature to the allele [15].

Considering the potential influence on the individual risk for DR due to the insertion-deletion mutation of -675 4G/5G, many studies have explored the association between PAI-1 4G/5G and DR risk [16–24]. However, individual studies yielded inconsistent and even conflicting findings, which might be caused by the limitation of individual studies. To shed light on these contradictory results and to get a more precise evaluation of this association, we performed a meta-analysis of nine published case-control studies covering 1, 217 cases and 1, 459 controls.

Methods

Search strategy

In this meta-analysis, a comprehensive literature research of the US National Library of Medicine's PubMed database (to 1 May 2012) was conducted using research terms including 'plasminogen activator inhibitor-1', 'PAI-1', '4G/5G', 'polymorphism', 'type 2 diabetes', 'diabetic retinopathy' and the combined phrases to obtain all genetic studies on the relationship between PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism and DR risk. There was no language limitation. We also hand-searched references of original studies or review articles on this topic to identify additional studies. The following criteria were used to select the eligible studies: they must be case-control studies on the association between PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism and DR; and they must contain detailed and correct numbers of different genotypes for estimating an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). When several publications reported on the same population data, the largest or most complete study was chosen. As a result, nine case-control studies were included in our meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently assessed the articles for inclusion or exclusion, resolved disagreements, and attained consistency. For each eligible study, the following information was recorded: the first author's name, the year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, total number of patients with DR and number of participants without DR (DWR) as well as the DR/DWR distribution in each PAI-1 genotype. Different ethnicities were categorized as Caucasian, Asian and Pima Indian. Sources of control were divided into population-based and hospital-based controls. The average duration of diabetes was separated into longer and shorter than 10 years.

Statistical analysis

The strength of the relationship between PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism and DR risk was assessed by calculating pooled ORs with 95% CIs. We evaluated the risk using the codominant model (4G/4G versus 5G/5G; 4G/5G versus 5G/5G), the dominant model (4G/4G + 4G/5G versus 5G/5G) and the recessive model (4G/4G versus 4G/5G + 5G/5G). Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated by χ2-based Q-test [25] and was considered significant if P < 0.10, in which case the random-effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method [26]) was used to pool the data. If P > 0.10, the fixed-effects model (the Mantel-Haenszel method [27]) was selected. These two models provided similar results when between-studies heterogeneity was absent. Begg's funnel plot, a scatter plot of effect against a measure of study size, was generated as a visual aid for detecting bias or systematic heterogeneity [28]. Publication bias was assessed by the linear regression asymmetry test by Egger et al. (P < 0.05 considered representative of statistical significance [29]). Studies were categorized into subgroups based on ethnicity, average diabetes duration, and source of control. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was tested by the χ2 test. All statistical analyses were performed in Review Manager (v.5.0; Oxford, England) and STATA Statistical Software (v.10.0; StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX). A two sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Eligible studies

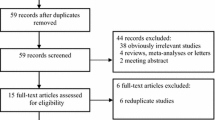

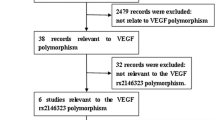

In total, nine case-control studies including 1, 217 cases and 1, 459 controls were selected in our meta-analysis. A flow chart of the literature search, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [30], is shown in Figure 1. The main characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 1. Among these eligible publications, there were five studies of Caucasians, three studies of Asians and one study of Pima Indians. Four studies in which the average diabetes duration in all the subgroups was longer than 10 years were enrolled together and compared with the other five studies in which the diabetes duration was shorter than 10 years. There were two population-based studies and seven hospital-based studies. All studies used PCR methods for genotyping. The genotype distributions in the controls of all studies were in agreement with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Thus, the sensitivity analysis was not performed in this study.

Meta-analysis

The main results of this meta-analysis and the heterogeneity test are shown in Table 2. Overall, we found a marginally statistical significant association between 4G/4G and DR risk in overall population (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.30, 95%CI 1.04 to 1.64, Figure 2; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: OR 1.26, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.52). In the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, significantly increased risks were observed among the Caucasian population (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.33, 95%CI 1.02 to 1.74; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: OR 1.41, 95%CI 1.13 to 1.77, Figure 3). In the stratified analysis by average diabetes duration, the PAI-1 variation was found associated with elevated DR risk in patients with a duration of diabetes longer than 10 years (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: OR 1.47, 95%CI 1.08 to 2.00, Figure 4). We also detected an increasing risk in hospital-based studies (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: OR 1.27, 95%CI 1.02 to 1.57, Figure 5).

Publication bias

The potential presence of publication bias was evaluated quantitatively by Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test. The Begg's funnel plot appeared symmetric. The Egger's test supported that there was no significant statistical evidence of publication bias for any of the four genetic models (for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G: P = 0.281; for 4G/4G versus 5G/5G + 4G/5G: P = 0.169; for 4G/5G versus 5G/5G: P = 0, 462; for 4G/4G + 4G/5G versus 5G/5G: P = 0.771). Figure 6 shows the shapes of the funnel plots of 4G/4G versus 5G/5G overall.

Discussion

Unraveling the genes that contribute to the pathogenic risk of DR has been one of the major foci of basic research in DR over the past few decades. A large number of putative genes and genetic variants have been reported to be associated with higher risk of DR. A genome-wide association study performed on Mexican-Americans found several SNPs and genes associated with severe DR. None of these loci have been previously linked to DR or diabetes itself [31]. Another genome-wide association study on Taiwanese populations identified five loci not previously associated with DR susceptibility in T2D [32]. This suggests that, until now, no genes have achieved widespread acceptance as conferring high risk of DR in patients with T2D [33]. After a review of the meta-analyses of DR-related gene polymorphisms, only the C677T polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene was detected to moderately augment the risk of DR in T2D overall [34, 35]. The Gly82Ser polymorphism in the receptor for advanced glycation end products gene might be considered a risk factor for DR in Asian populations. Moderate evidence was founded for a correlation between the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and proliferative DR [36]. However, neither the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion [36–38] nor the vascular endothelial growth factor -634C/G gene [39] showed a significant relationship with DR, either overall or in ethnicity subgroups in meta-analysis so far.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that PAI-1 4G/4G polymorphism was overall marginally significantly associated with DR risk in T2D. In the stratified analysis, significant associations were observed with Caucasian ethnicity, diabetes duration longer than 10 years and hospital-based studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis assessing the association between PAI-1 gene polymorphism and DR.

The earliest investigation into PAI-1 polymorphism and DR risk, reported by Nagi et al., revealed a positive relationship between the 4G allele of PAI-1 [19] and DR risk in Pima Indians, whose incidence of diabetes, particularly non-insulin-dependent diabetes, was extremely high [40, 41]. However, in the subsequent studies in Caucasian populations, a trend of studies with a lack of association was suggested [16, 18, 20, 21]. But in a recent larger case-control study in Tunisia that contained a total of 856 adult patients with T2D, Ezzidi et al. reported a significantly higher frequency of the 4G/4G genotype (OR 1.64, 95%CI 1.10 to 2.43), indicating 4G/4G in PAI-1 locus as a risk factor for DR [17]. All the studies in East Asian populations showed no relationship between 4G/5G polymorphism and DR risk [22–24]. Our meta-analysis confirmed that the 4G/4G genotype of the PAI-1 carried more risk in Caucasian but not Asian participants, even though the overall effect was positive. The differences in ethnic backgrounds, lifestyle, nutrition and living environment may partly explain this discrepancy [42]. We also found a marginally significant susceptibility to DR of T2D between PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism to the population with longer duration of T2D. This subgroup analysis manifested a gene-environment interaction and highlighted the need for implementing rigorous case-selective criterion in future studies.

We also observed inconsistent results between hospital-based studies and population-based studies, which may be explained by the biases in hospital-based studies. Control cases in hospital-based studies may be less representative of the general population than those from population-based studies. Genes do not work in isolation; instead, complex molecular networks and cellular pathways are often involved in disease susceptibility [43]. Taking into account that DR is a complex disease with multifactorial, polygenic and environmental influences, a minor contributing pathogenic role of the PAI-1 polymorphism in specific cases in DR and in co-operation with other factors cannot be totally excluded.

Several potential limitations existed in our meta-analysis and our results should be interpreted with caution. First, as no correction for multiple testing was performed in this meta-analysis, false positive results may have been induced in some fraction because of the application of multiple statistical tests, which would increase the probability of type I errors. Second, our meta-analysis is based on unadjusted estimates because of a lack of original data. For example, the accurate disease time-course of individual patients was unavailable, which may potentially have affected the results where our classification criterion was according to the mean value of the diabetes duration. Third, this meta-analysis was limited by the small sample size - especially in subgroup analysis - though the Egger's test gave no publication bias [44]. Fourth, the existing studies lacked information about potential gene-gene interactions. Last, genotyping methods were different among selected studies, which might affect results. This discrepancy indicates the need to implement rigorous quality control procedures in future studies.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis suggests that PAI-1 polymorphism may be associated with elevated DR risk in patients with T2D, especially in the Caucasian population and in patients who have had diabetes for longer than 10 years. Future larger scale epidemiological investigation of this topic should be conducted to validate our findings.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

confidence intervals

- DR:

-

diabetic retinopathy

- DWR:

-

diabetes without DR

- ORs:

-

odds ratios

- PAI-1:

-

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- T2D:

-

type 2 diabetes.

References

Hallman DM, Huber JC, Gonzalez VH, Klein BE, Klein R, Hanis CL: Familial aggregation of severity of diabetic retinopathy in Mexican Americans from Starr County, Texas. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 1163-1168. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1163.

Uhlmann K, Kovacs P, Boettcher Y, Hammes HP, Paschke R: Genetics of diabetic retinopathy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006, 114: 275-294. 10.1055/s-2006-924260.

Cilensek I, Mankoc S, Globocnik-Petrovic M, Petrovic D: The 4a/4a genotype of the VNTR polymorphism for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene predicts risk for proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Slovenian patients (Caucasians) with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Biol Rep. 2012, 39: 7061-7067. 10.1007/s11033-012-1537-8.

Petrovic MG, Cilensek I, Petrovic D: Manganese superoxide dismutase gene polymorphism (V16A) is associated with diabetic retinopathy in Slovene (Caucasians) type 2 diabetes patients. Dis Markers. 2008, 24: 59-64.

Churchill AJ, Carter JG, Ramsden C, Turner SJ, Yeung A, Brenchley PE, Ray DW: VEGF polymorphisms are associated with severity of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008, 49: 3611-3616. 10.1167/iovs.07-1383.

Hudson BI, Stickland MH, Futers TS, Grant PJ: Effects of novel polymorphisms in the RAGE gene on transcriptional regulation and their association with diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2001, 50: 1505-1511. 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1505.

Richeti F, Noronha RM, Waetge RT, de Vasconcellos JP, de Souza OF, Kneipp B, Assis N, Rocha MN, Calliari LE, Longui CA, Monte O, de Melo MB: Evaluation of AC(n) and C(-106)T polymorphisms of the aldose reductase gene in Brazilian patients with DM1 and susceptibility to diabetic retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2007, 13: 740-745.

Maeda M, Yamamoto I, Fukuda M, Nishida M, Fujitsu J, Nonen S, Igarashi T, Motomura T, Inaba M, Fujio Y, Azuma J: MTHFR gene polymorphism as a risk factor for diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients without serum creatinine elevation. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26: 547-548. 10.2337/diacare.26.2.547.

Sobrin L, Green T, Sim X, Jensen RA, Tai ES, Tay WT, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Sandholm N, Liu Y, Hietala K, Iyengar SK, Brooks M, Buraczynska M, van Zuydam N, Smith AV, Gudnason V, Doney AS, Morris AD, Leese GP, Palmer CN, Swaroop A, Taylor HA, Wilson JG, Penman A, Chen CJ, Groop PH, Saw SM, Aung T, Klein BE, et al: Candidate gene association study for diabetic retinopathy in persons with type 2 diabetes: the Candidate gene Association Resource (CARe). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011, 52: 7593-7602. 10.1167/iovs.11-7510.

Grant MB, Spoerri PE, Player DW, Bush DM, Ellis EA, Caballero S, Robison WG: Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 overexpression in retinal microvessels of PAI-1 transgenic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000, 41: 2296-2302.

Margaglione M, Cappucci G, d'Addedda M, Colaizzo D, Giuliani N, Vecchione G, Mascolo G, Grandone E, Di Minno G: PAI-1 plasma levels in a general population without clinical evidence of atherosclerosis: relation to environmental and genetic determinants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998, 18: 562-567. 10.1161/01.ATV.18.4.562.

Ashton N: Vascular basement membrane changes in diabetic retinopathy. Montgomery lecture, 1973. Br J Ophthalmol. 1974, 58: 344-366. 10.1136/bjo.58.4.344.

Henry M, Tregouet DA, Alessi MC, Aillaud MF, Visvikis S, Siest G, Tiret L, Juhan-Vague I: Metabolic determinants are much more important than genetic polymorphisms in determining the PAI-1 activity and antigen plasma concentrations: a family study with part of the Stanislas Cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998, 18: 84-91. 10.1161/01.ATV.18.1.84.

Stegnar M, Uhrin P, Peternel P, Mavri A, Salobir-Pajnic B, Stare J, Binder BR: The 4G/5G sequence polymorphism in the promoter of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) gene: relationship to plasma PAI-1 level in venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 1998, 79: 975-979.

Eriksson P, Kallin B, van 't Hooft FM, Bavenholm P, Hamsten A: Allele-specific increase in basal transcription of the plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1 gene is associated with myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995, 92: 1851-1855. 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1851.

Santos KG, Tschiedel B, Schneider J, Souto K, Roisenberg I: Diabetic retinopathy in Euro-Brazilian type 2 diabetic patients: relationship with polymorphisms in the aldose reductase, the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003, 61: 133-136. 10.1016/S0168-8227(03)00112-8.

Ezzidi I, Mtiraoui N, Chaieb M, Kacem M, Mahjoub T, Almawi WY: Diabetic retinopathy, PAI-1 4G/5G and -844G/A polymorphisms, and changes in circulating PAI-1 levels in Tunisian type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Metab. 2009, 35: 214-219. 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.12.002.

Globocnik-Petrovic M, Hawlina M, Peterlin B, Petrovic D: Insertion/deletion plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and insertion/deletion angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphisms in diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Ophthalmologica. 2003, 217: 219-224. 10.1159/000068975.

Nagi DK, McCormack LJ, Mohamed-Ali V, Yudkin JS, Knowler WC, Grant PJ: Diabetic retinopathy, promoter (4G/5G) polymorphism of PAI-1 gene, and PAI-1 activity in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997, 20: 1304-1309. 10.2337/diacare.20.8.1304.

Zietz B, Buechler C, Drobnik W, Herfarth H, Scholmerich J, Schaffler A: Allelic frequency of the PAI-1 4G/5G promoter polymorphism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and lack of association with PAI-1 plasma levels. Endocr Res. 2004, 30: 443-453. 10.1081/ERC-200035728.

Broch M, Gutierrez C, Aguilar C, Simon I, Richart C, Vendrell J: Genetic variation in promoter (4G/5G) of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene in type 2 diabetes. Absence of relationship with microangiopathy. Diabetes Care. 1998, 21: 463.

Murata M, Maruyama T, Suzuki Y, Saruta T, Ikeda Y: Paraoxonase 1 Gln/Arg polymorphism is associated with the risk of microangiopathy in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2004, 21: 837-844. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01252.x.

Wong TY, Poon P, Szeto CC, Chan JC, Li PK: Association of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 4G/4G genotype and type 2 diabetic nephropathy in Chinese patients. Kidney Int. 2000, 57: 632-638. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00884.x.

Liu SQ, Xue YM, Yang GC, He FY, Zhao XS: Relationship between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene 4G/5G polymorphism and type 2 diabetic nephropathy in Chinese Han patients in Guangdong Province. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2004, 24: 904-907.

Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH: Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997, 127: 820-826.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Mantel N, Haenszel W: Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959, 22: 719-748.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M: Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994, 50: 1088-1101. 10.2307/2533446.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315: 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009, 339: b2535-10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Fu YP, Hallman DM, Gonzalez VH, Klein BE, Klein R, Hayes MG, Cox NJ, Bell GI, Hanis CL: Identification of diabetic retinopathy genes through a genome-wide association study among Mexican-Americans from Starr County, Texas. J Ophthalmol. 2010, 2010: 861291.

Huang YC, Lin JM, Lin HJ, Chen CC, Chen SY, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ: Genome-wide association study of diabetic retinopathy in a Taiwanese population. Ophthalmology. 2011, 118: 642-648. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.020.

Liew G, Klein R, Wong TY: The role of genetics in susceptibility to diabetic retinopathy. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009, 49: 35-52.

Niu W, Qi Y: An updated meta-analysis of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene 677C/T polymorphism with diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012, 95: 110-118. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.009.

Zintzaras E, Chatzoulis DZ, Karabatsas CH, Stefanidis I: The relationship between C677T methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism and retinopathy in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Hum Genet. 2005, 50: 267-275. 10.1007/s10038-005-0250-z.

Zhou JB, Yang JK: Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism is associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2010, 47: 187-193.

Fujisawa T, Ikegami H, Kawaguchi Y, Hamada Y, Ueda H, Shintani M, Fukuda M, Ogihara T: Meta-analysis of association of insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene with diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. Diabetologia. 1998, 41: 47-53. 10.1007/s001250050865.

Wiwanitkit V: Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism is correlated to diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 2008, 22: 144-146. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.09.004.

Zhao T, Zhao J: Association between the -634C/G polymorphisms of the vascular endothelial growth factor and retinopathy in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010, 90: 45-53. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.05.029.

Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Bottazzo GF, Doniach D: Islet cell antibodies and diabetes mellitus in Pima Indians. Diabetologia. 1979, 17: 161-164. 10.1007/BF01219743.

Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hamman RF, Miller M: Diabetes incidence and prevalence in Pima Indians: a 19-fold greater incidence than in Rochester, Minnesota. Am J Epidemiol. 1978, 108: 497-505.

Hirschhorn JN, Lohmueller K, Byrne E, Hirschhorn K: A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet Med. 2002, 4: 45-61. 10.1097/00125817-200203000-00002.

Schadt EE: Molecular networks as sensors and drivers of common human diseases. Nature. 2009, 461: 218-223. 10.1038/nature08454.

Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA, Ntzani EE, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG: Genetic associations in large versus small studies: an empirical assessment. Lancet. 2003, 361: 567-571. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12516-0.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/1/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major And Key Programs of Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (30730099) and 'Project 211' - The Innovation Fund For Graduate Students of Tianjin Medical University (2009GSI20)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KXZ contributed to the idea and design of this study and revised the manuscript. TYZ and CP carried out the screening procedure, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. NDL participated in the design of the study, helped performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. EZ helped to improve the English language and gave some suggestions to this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Tengyue Zhang, Chong Pang contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Pang, C., Li, N. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 4G/5G polymorphism and retinopathy risk in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 11, 1 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-1