Abstract

Background

Several studies have found that primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are closely associated. However, the direction and causality of their interactions remain unclear. Thus, this study employs Mendelian Randomization to explore whether there are causal associations of genetically predicted PSC with IBD.

Methods

Genetic variants associated with the genome-wide association study (GWAS) of PSC were used as instrumental variables. The statistics for IBD, including ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease (CD) were derived from GWAS. Then, five methods were used to estimate the effects of genetically predicted PSC on IBD, including MR Egger, Weighted median (WM), Inverse variance weighted (IVW), Simple mode, and Weighted mode. Last, we also evaluated the pleiotropic effects, heterogeneity, and a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis that drives causal associations to confirm the validity of the analysis.

Results

Genetically predicted PSC was significantly associated with an increased risk of UC, according to the study (odds ratio [OR] IVW= 1.0014, P<0.05). However, none of the MR methods found significant causal evidence of genetically predicted PSC in CD (All P>0.05). The sensitivity analysis results showed that the causal effect estimations of genetically predicted PSC on IBD were robust, and there was no horizontal pleiotropy or statistical heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Our study corroborated a causal association between genetically predicted PSC and UC but did not between genetically predicted PSC and CD. Then, we identification of shared SNPs for PSC and UC, including rs3184504, rs9858213, rs725613, rs10909839, and rs4147359. More animal experiments and clinical observational studies are required to further clarify the underlying mechanisms of PSC and IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic intestinal disorder with unknown etiology. Many studies point to the presence of genetic predisposition, intestinal mucosal immune system dysfunction, and microbiota imbalance [1] in the occurrence and progression of IBD. Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are two main typical subtypes of IBD. The incidence of IBD has risen over the past decade in Asia. Predictably, the prevalence of IBD will significantly in the future, following an aging population [2].

Patients with IBD not only suffer a significant reduction in their quality of life but also causes substantial costs in health care due to its high prevalence [3]. Chronic IBD is restricted to the gut, but also in the extraintestinal organs in many patients [4, 5]. This phenomenon is called extraintestinal manifestations (EIM) of IBD. EIM frequently affects joints [6], skin [7], eyes [8], lungs [9], pancreas [10], and liver [11]. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is important EIM in IBD patients [4]. In clinical, about 70% of PSC patients are found to have underlying IBD [12,13,14]. Genetic risk factors, environmental factors, activation of the immune system, and microbiota have been assumed that the factors relevant to the pathogenesis of EIMs [15, 16]. For PSC, the association with the activity of the underlying IBD is unclear [17].

PSC is a type of autoimmune liver disease characterized by multi-focal bile duct strictures and progressive liver disease [18]. The prognosis of PSC was not satisfactory. Most patients ultimately require liver transplantation, after which disease recurrence may occur. However, without liver transplantation, the median survival time for PSC patients is 10 to 12 years [19].

Similar to IBD, the pathogenesis of PSC is also not well clear. However, the characteristic that PSC is often accompanied by IBD suggests that there may be a shared pathogenic gene or pathway between the PSC and IBD. Mendelian randomization (MR) renders us a novel way to study the connection between these two diseases. MR is a genetic epidemiological method, this method follows the Mendelian genetic law of "parental alleles are randomly assigned to offspring" [20]. This method uses single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer the potential causality of exposure and outcome. It’s beneficial to minimize bias caused by confounding factors and reverse causality [21]. Based on this, the MR method has been widely used to assess the causal relationship between traits and diseases or between diseases [22,23,24]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no MR studies inferring the potential causal relationship of PSC with IBD to date. Therefore, we applied the MR method to examine whether the genetically predicted PSC is associated with IBD.

Methods

Study design

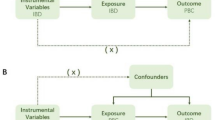

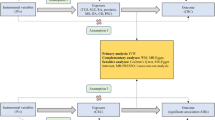

The overall design of Mendelian randomization analyses in this study is shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, (1) The selected instrumental variables were linked to exposure; (2) there were no inherent interactions between instrumental variables and confounder factors; (3) exposure was the only way by which instrumental variables can affect outcomes. The PSC served as the exposure, and UC served as the outcome. Since all datasets used in this study were based on public databases, no additional ethical approval was required.

GWAS data for PSC, UC, and CD

We gathered the summary statistics of PSC, UC, and CD, from the IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), all the cases there were defined on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), and fulfilled the clinical diagnosis criteria for IBD and PSC. To be more specific, the sample sizes of datasets for PSC, UC, and CD, are 14,890 cases, 463,010 cases, and 212,356 cases, respectively. PSC has 7, 891, 603 SNPs, UC has 9, 851, 867 SNPs, and CD has 16, 380, 455 SNPs. The detailed information on GWAS data is shown in Table 1.

Instrumental variable selection

All statistical analyses were performed by the R packages: TwoSampleMR. First, we selected SNPs related to PSC at the genome-wide significance threshold with p< 5 × 10-8. Because strong linkage disequilibrium could lead to biased results. Second, the independence among the selected SNPs was evaluated according to the pairwise-linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001, clumping window of 10,000 kb). When F-statistics were greater than 10, SNPs were considered powerful enough to mitigate the influence of potential bias. Third, we selected SNPs with F statistic >10 as IVs.

Statistical analysis

Based on the IVs, we performed an MR analysis to investigate the relationship between PSC and IBD. Five popular MR methods were used to analyze our data: MR Egger, Weighted median (WM), Inverse variance weighted (IVW), Simple mode, and Weighted mode. The IVW method is reported to be slightly more powerful than the others under certain conditions.

Cochran's Q statistics were used to perform heterogeneity, and p > 0.05 indicated no heterogeneity. Moreover, the MR-Egger method was used to determine the horizontal pleiotropy, MR-Egger at a p-value < 0.05 can imply the presence of horizontal pleiotropy.

Results

Selection of instrumental variables

After a series of quality control steps as mentioned above, 18 SNPs were selected as IVs (Table 2).

Causality relationship between PSC and IBD

Among the five MR methods, the causal effects of genetically predicted PSC on UC and CD were inconsistent. The results of the MR analyses were shown in Table 3, genetically predicted PSC was positively associated with a risk of UC in our study, with a p-value of IVW method less than 0.05. However, we found no evidence supporting a causal association between PSC and CD. Previous research indicated that the genome-wide genetic correlation between PSC and UC was significantly greater than that between PSC and CD [25], similar to our results.

The scatter plots were used to show the single SNP effect and the combined effects of each MR method (Fig. 2). Forest plots and funnel plots of the causal effect are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

According to this study, rs3184504, rs9858213, rs725613, rs10909839, and rs4147359 are shared SNPs for PSC and UC (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, heterogeneity, and horizontal pleiotropy to further verify the reliability of our results. The results of sensitivity analysis showed that the causal effect estimation of this study was robust. The MR-Egger (Q p-value 0.137) and IVW methods (Q p-value 0.214) showed no statistical heterogeneity. Furthermore, no statistical horizontal pleiotropy was found in the horizontal pleiotropy of MR-Egger methods (P=0.719). The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Discussion

The etiology of PSC and IBD remains unclear, and there is a lack of effective treatment methods. Now, the main treatment methods for PSC include bile composition modulators, immune modulators, anti-fibrotic, and regulation of the microbiome. However, further research is needed to determine whether these methods can delay its progression or improve transplant-free survival [26]. The same applies to the treatment of IBD. Although some new methods such as fecal transplantation, and small molecule drugs, applied to the treatment of IBD, satisfactory results have not been achieved in clinical yet [27,28,29]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the relationship between PSC and the subtype of IBD.

Previous studies have suggested an association between IBD and PSC or PBC [30, 31]. PSC is a prototypic gut-liver axis disease. In the patients of PSC, gut microbiota could disrupt the intestinal barrier, leading to bacterial translocation and Th17 cell-driven liver damage [32]. In contrast, the bile acid metabolizing enzyme CYP8B1 inhibits self-renewal of crypt based intestinal stem cells through the accumulation of its product bile acid, hinders intestinal epithelial barrier repair, and exacerbates inflammatory response [33]. These studies indicated a close correlation between intestinal diseases and liver diseases. As mentioned earlier, genetic predisposition plays a role in the occurrence and progression of IBD and PSC. The formation of serum antibodies is a way in which genetic factors affect the immune system. Multiple antibodies such as anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA) were upregulated in both autoimmune live diseases and IBD [34,35,36], and those antibodies may predict development of disease. The expression of common antibodies can also indicate a close relationship between the two diseases [37].

In this study, we used GWAS data to investigate the possible causal relationship and specific SNPs between PSC and IBD susceptibility, offering novel insights into the prevention and treatment of PSC and IBD. Multiple MR methods were employed to investigate the relationship between PSC and UC or CD, respectively. Four MR methods (Weighted median, Inverse variance weighted, Simple mode, and Weighted mode) indicated a significant relationship between PSC and UC. However, as for CD, there was no significant relationship between PSC and CD. Thus, we conclude that PSC has a significant relationship with UC but not CD. According this analysis, we also found the specific SNPs that are shared for PSC and UC (rs3184504, rs9858213, rs725613, rs10909839, and rs4147359). Except for chromosome 10 SNP (rs4147359), other SNPs have corresponding genes.

According to a previous study, the chromosome 12 SNP (rs3184504) was in the SH2B3 (SH2B adaptor protein 3) gene and is associated with autoimmune disease [38]. Multiple studies indicated that SH2B3 was related to the occurrence of autoimmune Hepatitis [39,40,41,42]. In addition, recent studies have shown that SH2B3 expressed in lymphocytes might with the risk of mid/long-term clinical relapse after being treated with infliximab in those patients with CD [43]. Although how SH2B3 mediates autoimmune disease remains unclear, a study provides us with new insights. Microbiome could exert physiological functions via the SH2B3 gene [44], and gut microbiota also exerts a significant influence on both PSC and UC [45, 46].

And rs9858213 is in the ring finger protein 123 (RNF123) gene, located in chromosome 3. The protein encoded by this gene displays E3 ubiquitin ligase activity toward the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B which is also known as p27 or KIP1, so the research on this gene is mainly focused on tumors now [47, 48]. A report indicated that p21 expression was higher in IBD cases [49]. Unfortunately, no studies have been reported that the relationship between rs9858213 and PSC.

T cells play an important role in both PSC and UC. Many studies focus on T-cell immunotherapy [50,51,52,53]. C-type lectin domain containing 16A (CLEC16A) gene which, has been proven associate with multiple immune-mediated diseases, which may through T cells to induce pathogenicity [54]. This connection validates our results from an immunological perspective.

For rs10909839, this SNP is located in the tetratricopeptide repeat domain 34 (TTC34) gene. TTC34 gene a link with systemic lupus erythematosus was reported by some studies [55, 56]. Unfortunately, there is limited research on this gene. Therefore, how TTC34 the immune system remains unknown.

We also acknowledge some of the limitations of this study. First, due to data availability, the GWAS data of UC and CD we used were from a European population, while the data of PSC was from a mixed population. In the future, more populations should be included. Second, only 18 SNPs meet the conditions to become IVs. Even if removing linkage disequilibrium, detecting pleiotropy, leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, heterogeneity analysis, and horizontal pleiotropy analysis have been conducted, we cannot guarantee that each SNP site meets the condition that instrumental variables can affect outcomes only through exposure. Some influence of unknown possible confounders inevitably affects our results. We obtained those results by analyzing data from public databases, but the databases didn’t provide clinical data. Therefore, experimental or other studies should be conducted to our results. Despite these limitations, our results may inspire possible mechanism analyses and the relationship between PSC and IBD, in the future.

Conclusions

Our study corroborated a causal association between genetically predicted PSC and UC but not for PSC and CD. Then, we identification of shared SNPs for PSC and UC, including rs3184504, rs9858213, rs725613, rs10909839, and rs4147359.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used in this study can be downloaded from the IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/).

References

Pittayanon R, Lau JT, Leontiadis GI, Tse F, Yuan Y, Surette M, Moayyedi P. Differences in gut microbiota in patients with vs without inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):930-946.e931.

Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(3):380–9.

Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–7.

Rogler G, Singh A, Kavanaugh A, Rubin DT. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1118–32.

Greuter T, Vavricka SR. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease - epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13(4):307–17.

Karreman MC, Luime JJ, Hazes JMW, Weel A. The prevalence and incidence of axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(5):631–42.

Marzano AV, Borghi A, Stadnicki A, Crosti C, Cugno M. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: pathophysiology, clinical features, and therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):213–27.

Taleban S, Li D, Targan SR, Ippoliti A, Brant SR, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Vasiliauskas EA, et al. Ocular manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease are associated with other extra-intestinal manifestations, gender, and genes implicated in other immune-related traits. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):43–9.

Eliadou E, Moleiro J, Ribaldone DG, Astegiano M, Rothfuss K, Taxonera C, Ghalim F, Carbonnel F, Verstockt B, Festa S, et al. Interstitial and Granulomatous Lung Disease in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(4):480–9.

Jasdanwala S, Babyatsky M. Crohn’s disease and acute pancreatitis. A review of literature. Jop. 2015;16(2):136–42.

Yarur AJ, Czul F, Levy C. Hepatobiliary manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(9):1655–67.

Bambha K, Kim WR, Talwalkar J, Torgerson H, Benson JT, Therneau TM, Loftus EV Jr, Yawn BP, Dickson ER, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence, clinical spectrum, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis in a United States community. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1364–9.

Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY, Holm K, Gotthardt D, Färkkilä MA, Marschall HU, et al. Patient age, sex, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotype associate with course of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1975-1984.e1978.

Da Cunha T, Vaziri H, Wu GY. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10(3):531–42.

Weizman A, Huang B, Berel D, Targan SR, Dubinsky M, Fleshner P, Ippoliti A, Kaur M, Panikkath D, Brant S, et al. Clinical, serologic, and genetic factors associated with pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):525–33.

Severs M, van Erp SJ, van der Valk ME, Mangen MJ, Fidder HH, van der Have M, van Bodegraven AA, de Jong DJ, van der Woude CJ, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. Smoking is associated with extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(4):455–61.

Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(8):1982–92.

Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1298–323.

Tischendorf JJ, Hecker H, Krüger M, Manns MP, Meier PN. Characterization, outcome, and prognosis in 273 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(1):107–14.

Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1925–6.

Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27(8):1133–63.

Endocrinology EoTLD: Expression of Concern-Estimating dose-response relationships for vitamin D with coronary heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality: observational and Mendelian randomisation analyses. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(1):e2–e11.

Björnson E, Adiels M, Taskinen MR, Burgess S, Rawshani A, Borén J, Packard CJ. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein remnants, low-density lipoproteins, and risk of coronary heart disease: a UK Biobank study. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(39):4186–95.

Zeng R, Wang J, Zheng C, Jiang R, Tong S, Wu H, Zhuo Z, Yang Q, Leung FW, Sha W, et al. Lack of causal associations of inflammatory bowel disease with parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Mov Disord. 2023;38(6):1082–8.

Ji SG, Juran BD, Mucha S, Folseraas T, Jostins L, Melum E, Kumasaka N, Atkinson EJ, Schlicht EM, Liu JZ, et al. Genome-wide association study of primary sclerosing cholangitis identifies new risk loci and quantifies the genetic relationship with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49(2):269–73.

Floreani A, De Martin S. Treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(12):1531–8.

Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, Connor S, Ng W, Paramsothy R, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1218–28.

Nielsen OH, Li Y, Johansson-Lindbom B, Coskun M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in inflammatory bowel disease. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(4):362–74.

Olivera PA, Lasa JS, Bonovas S, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases or other immune-mediated diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1554-1573.e1512.

Xie Y, Chen X, Deng M, Sun Y, Wang X, Chen J, Yuan C, Hesketh T. Causal Linkage Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front Genet. 2021;12:649376.

Zhao J, Li K, Liao X, Zhao Q. Causal associations between inflammatory bowel disease and primary biliary cholangitis: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10950.

Tilg H, Adolph TE, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab. 2022;34(11):1700–18.

Chen L, Jiao T, Liu W, Luo Y, Wang J, Guo X, Tong X, Lin Z, Sun C, Wang K, et al. Hepatic cytochrome P450 8B1 and cholic acid potentiate intestinal epithelial injury in colitis by suppressing intestinal stem cell renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29(9):1366-1381.e1369.

Muratori P, Muratori L, Guidi M, Maccariello S, Pappas G, Ferrari R, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, Bianchi FB. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) and autoimmune liver diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132(3):473–6.

Granito A, Zauli D, Muratori P, Muratori L, Grassi A, Bortolotti R, Petrolini N, Veronesi L, Gionchetti P, Bianchi FB, et al. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in coeliac disease before and after gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(7):881–7.

Granito A, Muratori P, Tovoli F, Muratori L. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA) in autoimmune diseases: a matter of laboratory technique and clinical setting. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(4):102787.

Israeli E, Grotto I, Gilburd B, Balicer RD, Goldin E, Wiik A, Shoenfeld Y. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as predictors of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2005;54(9):1232–6.

Mo X, Guo Y, Qian Q, Fu M, Zhang H. Phosphorylation-related SNPs influence lipid levels and rheumatoid arthritis risk by altering gene expression and plasma protein levels. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(4):889–98.

de Boer YS, van Gerven NM, Zwiers A, Verwer BJ, van Hoek B, van Erpecum KJ, Beuers U, van Buuren HR, Drenth JP, den Ouden JW, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with autoimmune hepatitis type 1. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):443-452.e445.

Umemura T, Joshita S, Hamano H, Yoshizawa K, Kawa S, Tanaka E, Ota M. Association of autoimmune hepatitis with Src homology 2 adaptor protein 3 gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients. J Hum Genet. 2017;62(11):963–7.

Chaouali M, Fernandes V, Ghazouani E, Pereira L, Kochkar R. Association of STAT4, TGFβ1, SH2B3 and PTPN22 polymorphisms with autoimmune hepatitis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2018;105(3):279–84.

Blombery P, Pazhakh V, Albuquerque AS, Maimaris J, Tu L, Briones Miranda B, Evans F, Thompson ER, Carpenter B, Proctor I, et al. Biallelic deleterious germline SH2B3 variants cause a novel syndrome of myeloproliferation and multi-organ autoimmunity. EJHaem. 2023;4(2):463–9.

Pierre N, Huynh-Thu VA, Marichal T, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Laharie D, Bourreille A, Colombel JF, Meuwis MA, Louis E. Distinct blood protein profiles associated with the risk of short-term and mid/long-term clinical relapse in patients with Crohn’s disease stopping infliximab: when the remission state hides different types of residual disease activity. Gut. 2023;72(3):443–50.

Brown JA, Sanidad KZ, Lucotti S, Lieber CM, Cox RM, Ananthanarayanan A, Basu S, Chen J, Shan M, Amir M, et al. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2105609.

Tabibian JH, Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Role of the microbiota and antibiotics in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:389537.

Larabi A, Barnich N, Nguyen HTT. New insights into the interplay between autophagy, gut microbiota and inflammatory responses in IBD. Autophagy. 2020;16(1):38–51.

Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Shomer I, Cohen-Kaplan V, Snijder B, Superti-Furga G, Gonen H, Sommer T, Ziv T, Admon A, Naroditsky I, et al. KPC1-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal processing of NF-κB1 p105 to p50 restricts tumor growth. Cell. 2015;161(2):333–47.

Gulei D, Drula R, Ghiaur G, Buzoianu AD, Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Tomuleasa C, Ciechanover A. The tumor suppressor functions of ubiquitin ligase KPC1: from cell-cycle control to NF-κB regulator. Cancer Res. 2023;83(11):1762–7.

Ioachim EE, Katsanos KH, Michael MC, Tsianos EV, Agnantis NJ. Immunohistochemical expression of cyclin D1, cyclin E, p21/waf1 and p27/kip1 in inflammatory bowel disease: correlation with other cell-cycle-related proteins (Rb, p53, ki-67 and PCNA) and clinicopathological features. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19(4):325–33.

Giuffrida P, Di Sabatino A. Targeting T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:105040.

Poch T, Krause J, Casar C, Liwinski T, Glau L, Kaufmann M, Ahrenstorf AE, Hess LU, Ziegler AE, Martrus G, et al. Single-cell atlas of hepatic T cells reveals expansion of liver-resident naive-like CD4(+) T cells in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(2):414–23.

Kvedaraite E. Neutrophil-T cell crosstalk in inflammatory bowel disease. Immunology. 2021;164(4):657–64.

Richardson N, Wootton GE, Bozward AG, Oo YH. Challenges and opportunities in achieving effective regulatory T cell therapy in autoimmune liver disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2022;44(4):461–74.

Schuster C, Gerold KD, Schober K, Probst L, Boerner K, Kim MJ, Ruckdeschel A, Serwold T, Kissler S. The autoimmunity-associated gene CLEC16A modulates thymic epithelial cell autophagy and alters T cell selection. Immunity. 2015;42(5):942–52.

Ross KA. Coherent somatic mutation in autoimmune disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101093.

Lanata CM, Nititham J, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Torgerson DG, Seldin MF, Pons-Estel BA, Tusié-Luna T, Tsao BP, Morand EF, et al. Genetic contributions to lupus nephritis in a multi-ethnic cohort of systemic lupus erythematous patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199003.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82372318, to JSP), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (No. 2022J02030, to JSP), and Major Research Project for Young and Middle-aged People of the Health Commission of Fujian Province (No. 2022ZQNZD004, to JSP). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: JSP and MZH. Data acquisition and analysis: XD and LLG. Writing of paper: XD. Critical revision of paper: JSP and MZH. Funds acquisition: JSP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, X., Gong, LL., Hong, MZ. et al. Investigating the shared genetic architecture between primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Gastroenterol 24, 77 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03162-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03162-6