Abstract

Background

Timely detection and management of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy is essential to improve outcomes. The objective of this study was to measure the performance of primary health care (PHC) workers in identifying comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy against a standardised reference diagnosis and a screening instrument in rural Ethiopia.

Methods

People with active convulsive epilepsy were identified from the community, with confirmatory diagnosis by trained PHC workers. Documented diagnosis of comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers was extracted from clinical records. The standardized reference measure for diagnosing mental disorders was the Operational Criteria for Research (OPCRIT plus) administered by psychiatric nurses. The mental disorder screening scale (Self-Reporting Questionnaire; SRQ-20), was administered by lay data collectors. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of PHC worker diagnosis against the reference standard diagnosis was calculated. Logistic regression was used to examine the factors associated with misdiagnosis of comorbid mental disorder by PHC workers.

Results

A total of 237 people with epilepsy were evaluated. The prevalence of mental disorders with standardised reference diagnosis was 13.9% (95% confidence interval (CI) 9.6, 18.2%) and by PHC workers was 6.3% (95%CI 3.2, 9.4%). The prevalence of common mental disorder using SRQ-20 at optimum cut-off point (9 or above) was 41.5% (95% CI 35.2, 47.8%). The sensitivity and specificity of PHC workers diagnosis was 21.1 and 96.1%, respectively, compared to the standardised reference diagnosis. In those diagnosed with comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers, only 6 (40%) had SRQ-20 score of 9 or above. When a combination of both diagnostic methods (SRQ-20 score ≥ 9 and PHC diagnosis of depression) was compared with the standardised reference diagnosis of depression, sensitivity increased to 78.9% (95% (CI) 73.4, 84.4%) with specificity of 59.7% (95% CI 53.2, 66.2%). Only older age was significantly associated with misdiagnosis of comorbid mental disorders by PHC (adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.02 to 1.11).

Conclusion

Routine detection of co-morbid mental disorder in people with epilepsy was very low. Combining clinical judgement with use of a screening scale holds promise but needs further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There have been a number of studies indicating the high prevalence of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy [1, 2]. The pooled prevalence of comorbid depression in people with epilepsy is estimated to be 22.9% (95% confidence interval (CI) 18.2–28.4%) and co-morbid anxiety disorders is 20.2% (95% CI 15.3–26.0%), based largely on studies from high-income countries (HIC) [2]. In hospital-based studies from sub-Saharan Africa, prevalence estimates for comorbid depression in people with epilepsy are even higher, e.g. 45.5% [3].

The relationship between epilepsy and mental disorders is complex [4]. There is an increased incidence (Incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.5–15.7) of depression, anxiety and psychotic disorders before the onset of epilepsy compared to people who do not develop epilepsy [5, 6]. The incidence of these mental disorders is also increased (IRR 2.2–10.9) after the diagnosis of epilepsy compared to people with no epilepsy [5]. The complex causal interrelationship between depression and epilepsy has been most investigated [6]. Functional and structural neuroimaging studies provide evidence of common neuropathology underlying the association between depression and epilepsy [4, 6]. Regardless of the nature of the relationship, the existence of co-morbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy has a detrimental effect on prognosis of epilepsy and quality of life [4] .

Early detection and appropriate management of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy is of paramount importance [4]. The evaluation should include lifetime and current history, family history of depressive, anxiety or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and psychotic disorder. However, in routine clinical practice there is under-detection and limited treatment of comorbid depression and anxiety in people with epilepsy (PWE) [7]. Failure to recognize and properly manage these comorbid disorders has serious impacts [7]. Those who are diagnosed with mood disorders before the onset of epilepsy have been found to have an increased risk of treatment resistant epilepsy [8] and of developing adverse side effects of anti-epileptic medications [9]. The risk of suicide is also increased three-fold in people with epilepsy compared to the those without epilepsy [10].

In low- and lower middle-income countries (LLMICs), the treatment gap (PWE who are not accessing or unable to access biomedical facilities for diagnosis and treatment and, if accessing biomedical treatment, those not adhering to the prescribed anti-epileptic drug (AED)) for active epilepsy ranges from 25 to 100% [11, 12], even before considering access to care for co-morbid mental health conditions. The treatment gap for mental disorders in the general population in LLMICs is high, ranging from 1.6–15.4% [13]. In recognition of the high treatment gap for both epilepsy and mental disorders globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends integrated management of priority mental, neurological and substance use disorders (MNS) at primary health care level [14, 15]. As part of this effort, the WHO has produced the mental health Gap Action Programme Intervention Guide (mhGAP-IG) comprising evidence-based clinical algorithms for MNS disorders that are suitable for non-specialist workers [14]. Epilepsy is included in mhGAP-IG, together with depression, psychosis, substance use disorders, suicidal behaviour, developmental disorders/child mental health problems, dementia and somatic/anxiety symptoms. Since its launch in 2008, there have been many efforts to adapt, implement and evaluate mhGAP, although there has been limited evaluation of the application of mhGAP-IG to people with co-morbid epilepsy and mental health disorders [16].

In Ethiopia, implementation of mhGAP in primary care settings has been shown to improve identification of people with psychosis and epilepsy [17], but not depression [18]. Qualitative exploration indicated unmet emotional needs in the people receiving mhGAP epilepsy care [19]. However, there have been very few studies to investigate the identification of comorbid mental disorders or the validation of common mental disorders screening instruments in people with epilepsy, especially in sub Saharan Africa [20]. The impact of using a locally validated screening tool on detection of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy was found to improve detection in Zambia [21, 22]. However, further studies are needed to evaluate and determine the detection of comorbidity among people with epilepsy in primary care settings in order to quantify the treatment gap, and to inform the design of interventions to increase detection.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the performance of primary health care (PHC) workers in detecting comorbid mental disorders, by comparing them to a screening scale and comparing their detection to a standardised reference diagnosis of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy in rural Ethiopia. It also tries to clarify the misdiagnosis of PHC in relation to the different sociodemographic factors.

Methods

Study design

In this paper we assessed the diagnostic performance of trained PHC workers compared to both self-report symptom questionnaires and standardised clinical assessments using data collected in a cross-sectional study. This study was nested within the baseline of a cohort study to measure the impacts of comorbid mental disorders on quality of life, functioning and seizure control in people with epilepsy in rural Ethiopia.

Setting

The study was conducted in four selected districts of the Gurage zone in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia. The zone is subdivided into 15 districts (woredas). The current study covered four of these 15 districts (Sodo, Eja, Wolikete and Kebena).

This study was part of the scale-up phase of the PRogramme for Improving Mental health CarE (PRIME) project [23]. PRIME was a research programme consortium across five low- and middle-income countries (Ethiopia, South Africa, Uganda, India and Nepal) that aimed to develop comprehensive evidence for the best strategy to integrate and scale up mental health care incorporated within primary health care settings. The PRIME-Ethiopia study focused on four priority MNS disorders, based on their associated disability and prioritisation by the Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia: psychosis, depression, epilepsy and alcohol use disorders. In PRIME, researchers worked with community stakeholders using a participatory process to develop a district mental health care plan [24, 25] which included delivery of mhGAP-IG in primary healthcare facilities, as well as interventions for community mobilisation and health system strengthening [24]. Health workers staffing primary healthcare facilities are health officers and nurses, but not physicians. PRIME had three phases: inception, implementation and scale up phases. Therefore, the PRIME project has major role in this study for the integration of mental health care in the primary health care facilities and training of the PHC workers in mhGAP-IG. One health centre from each district of the Gurage zone was selected as part of the scale up phase of PRIME [26].

In this study we included scale-up health centres of the PRIME project which were accessible and where there were sufficient numbers of people with epilepsy attending (n = 3 health centres). We additionally included health centres from the PRIME implementation site (n = 8 facilities) in the district of Sodo.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated for the cohort study within which this study was nested [27].

Study participants

Detection and referral of people with probable active convulsive epilepsy whether they were on treatment or not was carried out by community key informants and health extension workers (HEWs) who had been trained for 2 days in case recognition. The diagnosis was then confirmed by PHC workers in the health centres who had been trained in mhGAP-IG. Recruitment into the study took place at the point when the identified person had attended the health centre. After the PHC worker had confirmed the diagnosis of active convulsive epilepsy, they assessed the person and developed a treatment plan in accordance with the mhGAP-IG manual, including prescription of antiepileptic medication and psychotropic medication or psychological support, as indicated regardless of their consent to participate into the study. No diagnostic investigations (e.g. Electroencephalogram EEG) were used to confirm the diagnosis of epilepsy, which is in keeping with mhGAP-IG recommendations, designed to be pragmatic in low-resource settings. A research psychiatric nurse screened potential participants for eligibility, assessed for capacity to consent to participate in the study and obtained informed consent before a person was recruited into the study. This psychiatric nurse did not interact with the PHC workers or provide any assistance with diagnosis.

Eligibility criteria were as follows: i) PHC worker diagnosis of active convulsive epilepsy based on the WHO mhGAP-IG, ii) aged 18 years or above, iii) no plans to out-migrate in the next 12 months, and iv) able to converse in Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia. Participants were excluded if there were communication difficulties due to cognitive or intellectual disability or lack of capacity to consent.

Screening instrument

The Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20)- was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to screen for common mental disorder symptoms at primary health care level [28]. The SRQ-20 has been used in various population groups including the elderly and in people with other psychiatric disorders [28]. The instrument has 20 questions with “yes/no” answers and it can be easily administered by an interviewer. Total score on SRQ-20 for a given person ranges from 0 to 20. The 20 items of SRQ-20 cover depressive, anxiety, somatic symptoms and suicidal ideation present in the past 30 days.

The SRQ-20 has been translated into Amharic and has been validated in postnatal women [29] and at primary health care level [30]. It has been culturally adapted and investigated for semantic, content and technical validity in Ethiopia [29, 31] although never in the context of people with epilepsy. Exploratory factor analysis using data collected at a primary health care level in rural Ethiopia produced a single factor structure [30].

Standardised reference measure of mental disorders

A semi-structured clinical interview, the Operational Criteria for Research+ (OPCRIT plus) was used as the standardized reference measure of mental disorders [32]. The original OPCRIT consists of an electronic psychopathological checklist of items for diagnosis of psychosis and affective disorders [33]. OPCRIT+ was redeveloped with an expansion of items for additional affective, anxiety, substance use and personality disorders [32]. It also includes items for assessment of risk, psychosocial status and prognosis. The OPCRIT+ provides a simple and reliable method of applying multiple operational diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of a broad range of psychiatric disorders [32]. OPCRIT+ has been used in extensively in the same setting by psychiatry nurses and psychiatrists [34, 35]. It has shown to have good interrater reliability, with a weighted kappa of 0.70 for diagnostic reliability [32].

Other measures

Socio-demographic and epilepsy-related characteristics were measured using self-report questions for age, gender, educational status, relative wealth, and occupation, types of seizure, seizure frequency / month and duration of epilepsy.

Data collection and management

The SRQ-20 was administered by experienced lay data collectors who had completed secondary school education. The OPCRIT+ was administered by psychiatric nurses. The psychiatric nurses had previous training and experience of administering OPCRIT+ [35]. The detection of comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers was evaluated by review of the clinical documentation following consultation. The administration of the SRQ-20 and OPCRIT+ was carried out after the study participants were evaluated by PHC.

To avoid an order effect, the order of administration of the SRQ-20 and the OPCRIT+ assessment was randomised. Both administrators (lay data collectors and psychiatric nurses) were masked to the outcome of the assessment done by the other administrator.

Immediately after the completion of the data collection, the field supervisor checked that all the items of the questionnaire had been completed. All data were kept in a secure cupboard in the project office. Data were anonymised, identifiable through a unique project identification number.

Data analysis

The data were double entered using Epi-data version 3.1 and analysed using STATA version 12 [36]. Descriptive statistics using percentages were presented for each of the detection methods (PHC worker, symptom screen and clinical diagnosis). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of PHC diagnosis against the standardised reference of psychiatric nurse diagnosis was calculated.

The total score of the SRQ-20 was used. The Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC) was plotted by including only those people diagnosed to have common mental disorders (depression and anxiety disorders) and taking the psychiatric nurse diagnosis of a mental disorders as a gold standard. The optimal cut off point of SRQ was determined based on the maximum specificity (% of true negatives detected by the SRQ-20) not higher than the sensitivity (% of true positives detected by the SRQ-20). Based on the optimal cut-off score for SRQ-20, the specificity, sensitivity, positive and negative predictive value and Youden’s index (specificity and sensitivity-1) were calculated. The sensitivity and specificity of the combined methods of the PHC diagnosis augmented by the SRQ-20 against the OPCRIT + was also calculated.

Pearson’s chi squared test was used to examine the difference in the reports of each items of SRQ-20 between those with or without depression diagnosed by PHC workers and compared to those diagnosed by psychiatric nurses.

Logistic regression was used to examine the factors which were associated with misdiagnosis of comorbid mental disorder by PHC workers.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 246 people with epilepsy (PWE) attended the 11 health centres in the four districts for evaluation. Of these, 237 were eligible and were recruited into the study. Seven people did not fulfil the eligibility criteria and the data of two participants were incomplete. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. All participants were diagnosed with generalised seizures, with a median of one seizure per month. Of the total sample, 89.5% (n = 212) had received biomedical treatment previously (at any time) before being recruited to this study.

Standardised reference diagnosis of mental disorder

The prevalence of mental disorders according to the OPCRIT+ was 13.9% (95% confidence interval (CI) 9.6, 18.2%). Major depressive disorder (MDD) was the most common comorbid disorder (7.2%, n = 17), followed by alcohol use disorder (AUD) (2.5%, n = 6), then psychosis (2.1%, n = 5). One individual (0.4%) was diagnosed as having both MDD and AUD (0.4%). The prevalence of dysthymia was 0.8% (n = 2) and that of bipolar disorder was 0.8% (n = 2). An equal number of males (10) and females (10) were diagnosed with depression and dysthymia by the psychiatric nurse using OPCRIT+.

PHC worker diagnosis of mental disorder

Based on the chart review of study participants, 6.3% (95%CI 3.2, 9.4%) of the people with epilepsy were diagnosed by PHC workers as having comorbid mental disorders: 3.4% (n = 8) with MDD, 1.7% (n = 4) with psychosis and 1.3% (n = 3) with AUD. Of the 8 people with a diagnosis of depression by PHC workers, six were males. The sensitivity and specificity of PHC diagnosis was 21.1 and 96.1%, respectively, compared to the standardised reference diagnosis. The positive predictive value (PPV) of PHC worker diagnosis was 46.7% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 88.3%.

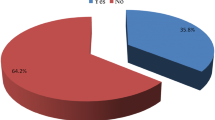

SRQ-20

The total SRQ-20 score was positively skewed. The median score was 7 with IQR of 3–12. When the SRQ-20 score was compared with the standardised reference diagnosis, the optimum cut-off score of SRQ-20 indicating common mental disorder was greater or equal to 9. The area under the ROC of SRQ-20 was 0.74 with 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62 to 0.82. At this cut-off, 62.1% of participants were classified correctly, although the PPV was very low (15.1%) (See Table 2). The prevalence of common mental disorder at this cut-off (9 or above) was 41.5%.

Out of the 15 individuals diagnosed to have comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers, only 6 (40%) had an SRQ-20 score of 9 or above.

In people with a PHC worker diagnosis of depression, the most frequently endorsed SRQ-20 items were loss of interest, feeling frightened and getting easily tired. However, there was no significant differences in the reporting of these symptoms between those with or without a PHC worker depression diagnosis. There were multiple depressive and somatic symptoms which discriminated between those with and without standardised reference depression diagnosis by psychiatric nurses (see Table 3).

The combination of both diagnostic methods (the SRQ-20 score above the optimum cut off augmented by PHC diagnosis of depression) was also compared with the standardised reference diagnosis of depression. The sensitivity of this combined approach was 78.9% (95% confidence interval (CI) 73.4, 84.4%) with specificity of 59.7% (95% CI 53.2, 66.2%). However, the PPV was low, at 15.6%.

Factors associated with misdiagnosis of comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers were also examined. As shown in Table 4, only age was significantly associated with misdiagnosis of comorbid mental disorders by PHC workers (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.06, 1.02 1.11 for every increasing year of age).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional survey, the performance of primary health care (PHC) workers in diagnosing comorbid mental disorders against a standardised measure and a screening instrument (SRQ-20) for common mental disorders was examined. The sensitivity of the PHC workers’ diagnoses was low, although they had high specificity in relation to the standardised reference diagnosis. The psychometric properties of SRQ-20 indicate an optimal cut-off score of 9 and above, with moderate sensitivity and specificity but low positive predictive value. When the two diagnostic methods (SRQ-20 screening augmented by PHC workers diagnosis) were combined, the sensitivity was markedly improved but the positive predictive value remained low. Misdiagnosis of comorbidity by PHC worker was significantly associated with increasing age.

The low sensitivity of the PHC workers in detection of depression in our study sample is consistent with other studies carried out in Ethiopia and other parts of the world [18, 37,38,39]. In this current study, less than half (45.5%) of the people with epilepsy and comorbid mental disorders were detected by PHC. Very little research attention has been paid to investigating the detection of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy in routine clinical practice in low-income country settings [22]. Under detection and management of comorbid common mental disorders has consistently been found to be a problem in high income countries (HIC), despite the high prevalence of co-morbidity in people with epilepsy [7, 40]. One of the reasons identified for this under-detection is the soloed approach to care for people with epilepsy and mental health conditions, both in terms of inadequate training of neurologists in the psychiatric aspects of mental disorders and poor communication between the neurologist and psychiatrist [40]. In addition, failure of the training programme on psychiatric aspects of commonly occurring neurologic disorders for psychiatry residents, lack of interest in neurologic literature and the absence of psychiatrist in the team of neurologists were seen in a study from the USA [40].

This issue in low income countries like Ethiopia is different from the HIC where more frontline management of epilepsy is expected to be carried out in primary care, with little access to either neurologists or psychiatrists [24]. Health professionals working at the primary health care level are also expected to detect and manage five priority mental disorders based on their training through mhGAP [24]. It was shown previously that the PHC workers in rural primary health care in Ethiopia were more likely to detect people who presented with psychological than somatic symptoms, even though somatic symptoms are the more common presenting symptoms, and tended to detect those who had more severe forms of depression [18]. There were also multiple system and individual level barriers for under detection of depression by PHC workers. Some of these barriers included poor training of the PHC workers on mental disorders, non-biomedical explanatory models of mental disorders by patients and their family members, and somatic symptoms being the common presenting complaints of the patients [18]. In people with epilepsy, overlaps between symptoms of depression and the side effects of older classes of antiepileptic medications (e.g. phenobarbitone, phenytoin) makes early detection of depression challenging [41].

The sensitivity of SRQ-20 in screening for depression was not at a satisfactory level in people with epilepsy but the scale performed relatively well in the general population of Ethiopia and in a similar setting of Eritrea [30, 42, 43]. There is minimal evidence on the validation of SRQ-20 in special populations like people with epilepsy which has made it difficult to compare our findings to previous work. Systematic reviews of validation studies of screening instruments for common mental disorders in LMICs in the general population have shown that the instruments with best performance are those which have been locally developed from scratch for specific population in a specific setting [44]. The SRQ-20 is unusual because it was developed with LMIC contexts in mind, drawing on symptoms from scales used in both HIC and LMIC settings [28]. In the previous studies of SRQ-20 in Ethiopia, the local adaptation and attempts to make the instrument culturally sensitive are likely to have contributed to the observed validity [42]. However, in people with epilepsy, the high number of somatic items on the SRQ-20 may overlap with impacts of inadequately controlled epilepsy (e.g. on sleep) and the effects of antiepileptic drug side effects [45].

Less than half of the participants diagnosed by the PHC workers as having comorbid mental disorders scored above the optimum cut off point of SRQ-20. Specific items of the SRQ-20 were not differentially reported by the participants diagnosed to have comorbid depression by the PHC workers. This could be due to the small number of participants diagnosed to have comorbid depression by the PHC workers. Some of the somatic and depressive symptom items of SRQ-20 were also highly prevalent in both population (with or without depression). It has been previously shown in the same setting that people with depression spontaneously reported symptoms which are partially represented in the typical diagnostic criteria [46]. The concept of depression was not well recognized as an illness in this community unless it is usually associated with disruption of function [46]. Since the PHC workers working in rural settings are usually accustomed to the cultural ways of expressing distress, this could be inconsistent with the symptoms of depression represented in SRQ-20 and reduce the sensitivity.

This study has also demonstrated that use of the two methods (SRQ-20 screening augmented by the clinical evaluation) of detection comorbidity of depression is promising. This augmentation is seen by the high specificity of PHC workers which has compensated for the low specificity of SRQ-20. As people with epilepsy are a high risk population, the routine use of depression screening is highly recommended in HIC [7]. It is also recommended that the ideal screening tool should be able to detect depression even when patients are presenting with somatic complaints [47]. PHC workers knowing the common terms patients use for emotional symptoms and their relevance will help in identification of mental disorders [47]. However, in our study, the screening questionnaire was administered by research staff and was not used as part of clinical decision-making. Implementation of screening questionnaires for depression in routine PHC settings has yielded mixed results in high-income countries [48], indicating the need for future studies to evaluate the effectiveness of introduction of routine screening in people with epilepsy in LLMICs.

The inclusion and evaluation of three different diagnostic methods simultaneously in routine clinical care was one of the strengths of this study. It is also one of the few studies carried out on detection of comorbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. The results of this study indicate that attention needs to be focused on improving the detection of co-morbid mental health problems integrated within the scale-up of primary care-based mental health care in Ethiopia and similar settings. This study was a pragmatic study which has followed mhGAP-IG criterion for evaluation of people with epilepsy. The use of psychiatric nurses for the standardised clinical assessment rather than psychiatrists means that it may not be considered a gold standard. However, in the Ethiopian setting, psychiatric nurses take on additional clinical roles compared to their counterparts in high-income countries, including diagnostic assessment, and would have had experience and competence in this area. Even though OPCRIT+ allows local clinicians to probe and explore responses in a flexible way, it has not been validated in this specific context. The other limitation of this study was the absence of people with non-generalized seizures. This is likely to be because of the limited clinical experience of PHC workers in management of mental or neurological disorders before the implementation of mhGAP. Even after the mhGAP training the diagnosis of focal seizures and non-epileptic seizures needs experience and an EEG. Neither the primary health care facility nor the PHC workers are equipped with this skill or resource. The low detection of anxiety disorders in this study could also be due to the presentation of depression in Ethiopian culture, which tends to be a combination of anxiety, somatic and depressive symptoms rather than typical DSM criteria, alongside the non-biomedical causal attributions of depressive/anxiety symptoms in this society [27]. It is possible that psychiatry nurses tended to prioritise a diagnosis of depression over anxiety disorders as this reflected their experince of presentation in clinical settings.

Further, studies are needed on interventions to increase detection. The development, cultural adaptation and evaluation of the impact of symptom screening tools in routine settings is a promising avenue for future research. Training programmes for PHC workers in LMICs, such as mhGAP, may benefit from a more horizontally integrated diagnostic algorithms which facilitate detection of co-morbidity. Contextualisation using local expression of mental distress may also increase the impact on detection.

Conclusion

In conclusion the detection of co-morbid mental disorders in people with epilepsy by PHC workers was low. The use of screening instruments augmented by the clinical skill of the PHC workers may possibly improve the detection of mental disorders but needs further evaluation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article as an Additional file 1- Data set.

Abbreviations

- HIC:

-

High-income countries

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- LLMICs:

-

Low- and lower middle-income countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MNS:

-

Mental neurological and substance use disorders

- mhGAP-IG:

-

Mental health Gap Action Programme Intervention Guide

- PHC:

-

Primary health care

- SNNPR:

-

Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region

- PRIME:

-

PRogramme for Improving Mental health CarE

- HEW:

-

Health extension workers

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- SRQ-20:

-

Self Reporting Questionnaire

- OPCRIT+:

-

Operational Criteria for Research

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve

- PWE:

-

People with epilepsy

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- AUD:

-

Alcohol use disorder

References

Josephson CB, Jetté N. Psychiatric comorbidities in epilepsy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):409–24.

Scott AJ, Sharpe L, Hunt C, Gandy M. Anxiety and depressive disorders in people with epilepsy: a meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(6):973–82.

Dessie G, Mulugeta H, Leshargie CT, Wagnew F, Burrowes S. Depression among epileptic patients and its association with drug therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0202613.

Kanner AM. Psychiatric comorbidities in new onset epilepsy: should they be always investigated? Seizure. 2017;49:79–82.

Hesdorffer DC, Ishihara L, Mynepalli L, Webb DJ, Weil J, Hauser WA. Epilepsy, suicidality, and psychiatric disorders: a bidirectional association. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(2):184–91.

Kanner AM, Schachter SC, Barry JJ, Hersdorffer DC, Mula M, Trimble M, et al. Depression and epilepsy: epidemiologic and neurobiologic perspectives that may explain their high comorbid occurrence. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24(2):156–68.

Kanner AM. Obstacles in the treatment of common psychiatric comorbidities in patients with epilepsy: what is wrong with this picture? Epilepsy Behav. 2019;98:291–2.

Josephson CB, Lowerison M, Vallerand I, Sajobi TT, Patten S, Jette N, et al. Association of depression and treated depression with epilepsy and seizure outcomes: a multicohort analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):533–9.

Kanner AM, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Hermann B, Meador KJ. Depressive and anxiety disorders in epilepsy: do they differ in their potential to worsen common antiepileptic drug–related adverse events? Epilepsia. 2012;53(6):1104–8.

Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB, Sidenius P, Agerbo E. Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case–control study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):693–8.

Newton CR, Garcia HH. Epilepsy in poor regions of the world. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1193–201.

Mbuba CK, Ngugi AK, Newton CR, Carter JA. The epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries: a systematic review of the magnitude, causes, and intervention strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(9):1491–503.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50.

World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). World Health Organization; 2016.

World Health Organization. mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Keynejad R, Spagnolo J, Thornicroft G. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evid Based Mental Health. 2021;24:124–30.

Ayano G, Assefa D, Haile K, Bekana L. Experiences, strengths and challenges of integration of mental health into primary care in Ethiopia. Experiences of East African Country. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2016;5(204):2.

Fekadu A, Medhin G, Selamu M, Giorgis TW, Lund C, Alem A, et al. Recognition of depression by primary care clinicians in rural Ethiopia. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):56.

Catalao R, Eshetu T, Tsigebrhan R, Medhin G, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Implementing integrated services for people with epilepsy in primary care in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):372.

Sebera F, Vissoci JRN, Umwiringirwa J, Teuwen DE, Boon PE, Dedeken P. Validity, reliability and cut-offs of the patient health Questionnaire-9 as a screening tool for depression among patients living with epilepsy in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234095.

Mbewe EK, Uys LR, Nkwanyana NM, Birbeck GL. A primary healthcare screening tool to identify depression and anxiety disorders among people with epilepsy in Zambia. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27(2):296–300.

Mbewe EK, Uys LR, Birbeck GL. The impact of a short depression and anxiety screening tool in epilepsy care in primary health care settings in Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(5):873–4.

Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, et al. PRIME: A Programme to Reduce the Treatment Gap for Mental Disorders in Five Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS Med. 2012;9(12):e1001359.

Fekadu A, Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Selamu M, Giorgis TW, et al. Development of a scalable mental healthcare plan for a rural district in Ethiopia. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(s56):s4–s12.

Hailemariam M, Fekadu A, Selamu M, Alem A, Medhin G, Giorgis TW, et al. Developing a mental health care plan in a low resource setting: the theory of change approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):429.

De Silva MJ, Rathod SD, Hanlon C, Breuer E, Chisholm D, Fekadu A, et al. Evaluation of district mental healthcare plans: the PRIME consortium methodology. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(Supplement 56):s63–70.

Tsigebrhan R, Fekadu A, Medhin G, Newton CR, Prince MJ, Hanlon C. Comorbid mental disorders and quality of life of people with epilepsy attending primary health care clinics in rural Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0238137.

Beusenberg M, Orley JH, Organization WH. A User's guide to the self reporting questionnaire SRQ. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Araya M, Abdulahi A, Hughes M, et al. Detecting perinatal common mental disorders in Ethiopia: validation of the self-reporting questionnaire and Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(3):251–62.

Hanlon C, Medhin G, Selamu M, Breuer E, Worku B, Hailemariam M, et al. Validity of brief screening questionnaires to detect depression in primary care in Ethiopia. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:32–9.

Kortmann F, Ten Horn S. Comprehension and motivation in responses to a psychiatric screening instrument validity of the SRQ in Ethiopia. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153(1):95–101.

Rucker J, Newman S, Gray J, Gunasinghe C, Broadbent M, Brittain P, et al. OPCRIT+: an electronic system for psychiatric diagnosis and data collection in clinical and research settings. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):151–5.

McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I. A Polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:764–70.

Fekadu A, Mesfin M, Medhin G, Alem A, Teferra S, Gebre-Eyesus T, et al. Adjuvant therapy with minocycline for schizophrenia (the MINOS trial): study protocol for a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):406.

Hanlon C, Medhin G, Selamu M, Birhane R, Dewey M, Tirfessa K, et al. Impact of integrated district level mental health care on clinical and social outcomes of people with severe mental illness in rural Ethiopia: an intervention cohort study. Cambridge University Press. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e45.

Hamilton LC. Statistics with Stata: version 12: Cengage learning; 2012.

Udedi M. The prevalence of depression among patients and its detection by primary health care workers at Matawale health Centre (Zomba). Malawi Med J. 2014;26(2):34–7.

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609–19.

Fekadu A, Demissie M, Birhane R, Medhin G, Bitew T, Hailemariam M, et al. Under detection of depression in primary care settings in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.03.20.20039628.

Lopez MR, Schachter SC, Kanner AM. Psychiatric comorbidities go unrecognized in patients with epilepsy:“you see what you know”. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;98:302–5.

Robertson MM, Trimble MR, Townsend H. Phenomenology of depression in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1987;28(4):364–72.

Kortmann F. Psychiatric case finding in Ethiopia: shortcomings of the self reporting questionnaire. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1990;14(3):381–91.

Netsereab TB, Kifle MM, Tesfagiorgis RB, Habteab SG, Weldeabzgi YK, Tesfamariam OZ. Validation of the WHO self-reporting questionnaire-20 (SRQ-20) item in primary health care settings in Eritrea. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2018;12(1):1–9.

Ali G-C, Ryan G, De Silva MJ. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156939.

Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(5):399–405.

Tekola B, Mayston R, Eshetu T, Birhane R, Milkias B, Hanlon C, et al. Understandings of depression among community members and primary healthcare attendees in rural Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Transcult Psychiatry. 2020.

Kerr LK, Kerr LD Jr. Screening tools for depression in primary care: the effects of culture, gender, and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. West J Med. 2001;175(5):349.

Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2008;178(8):997–1003.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the participants and their families, the PRIME project and all its staff.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of a Wellcome Trust fellowship for RT (Grant Number 104023/Z/14/A) and a PhD fellowship from CDT-Africa. The study was nested within the PRogramme for Improving Mental health carE (PRIME). PRIME was funded by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) [201446]. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. CH is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King’s College London (GHRU 16/136/54). The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. CH additionally receives support from AMARI as part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RT, CH, AF, MP and CN participated in the writing of the research proposal. RT contributed in the collection of the data. RT, GM and CH analysed the data. RT drafted the manuscript. RT, CH, GM, AF, CN and MP made intellectual contribution and revised the draft. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University and the Research Ethics Committee of King’s College London (HR-15/16–2434). The information sheet contained all the details of the study and potential benefits and risks associated with being part of the study. Adequate amount of time was given to process the information, ask questions and no coercion to participate was implied. After the psychiatric nurse assessed the capacity to consent, for non-literate participants an independent witness confirmed to the potential participant that the information sheet has been conveyed accurately and signed to this effect. All people participating in this study were adults and had capacity to give informed consent. If the person was non-literate they signified their consent through a finger print, but an independent witness was present purely to confirm to the non-literate person that the information sheet had been read out and explained in keeping with what was written. This kind of recruitment have been approved by the WHO accredited Addis Ababa University research ethics committee. They were also assured that no matter what their decision was the treatment and the relationship with their clinician or the services of the health facility would not be affected. Informed consent and witnessed verbal consent (for non-literate participants) was sought after adequate information had been provided about the study. Confidentiality was maintained by storing the data in locked cabinets and password protected computers. The questionnaires were anonymised with a unique identification number.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Data set.

Performance of primary health care workers in detection of mental disorders comorbid with epilepsy in rural Ethiopia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsigebrhan, R., Fekadu, A., Medhin, G. et al. Performance of primary health care workers in detection of mental disorders comorbid with epilepsy in rural Ethiopia. BMC Fam Pract 22, 204 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01551-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01551-4