Abstract

Psychometrically sound resilience outcome measures are essential to establish how health and care services or interventions can enhance the resilience of people living with dementia (PLWD) and their carers. This paper systematically reviews the literature to identify studies that administered a resilience measurement scale with PLWD and/or their carers and examines the psychometric properties of these measures. Electronic abstract databases and the internet were searched, and an international network contacted to identify peer-reviewed journal articles. Two authors independently extracted data. They critically reviewed the measurement properties from the available psychometric data in the studies, using a standardised checklist adapted for purpose. Fifty-one studies were included in the final review, which applied nine different resilience measures, eight developed in other populations and one developed for dementia carers in Thailand. None of the measures were developed for use with people living with dementia. The majority of studies (N = 47) focussed on dementia carers, three studies focussed on people living with dementia and one study measured both carers and the person with dementia. All the studies had missing information regarding the psychometric properties of the measures as applied in these two populations. Nineteen studies presented internal consistency data, suggesting seven of the nine measures demonstrate acceptable reliability in these new populations. There was some evidence of construct validity, and twenty-eight studies hypothesised effects a priori (associations with other outcome measure/demographic data/differences in scores between relevant groups) which were partially supported. The other studies were either exploratory or did not specify hypotheses. This limited evidence does not necessarily mean the resilience measure is not suitable, and we encourage future users of resilience measures in these populations to report information to advance knowledge and inform further reviews. All the measures require further psychometric evaluation in both these populations. The conceptual adequacy of the measures as applied in these new populations was questionable. Further research to understand the experience of resilience for people living with dementia and carers could establish the extent current measures -which tend to measure personal strengths -are relevant and comprehensive, or whether further work is required to establish a new resilience outcome measure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Measurement is an essential aspect of scientific research and evaluations of interventions and policies require reliable and valid outcome measures [1]. A twelve-country European working group of researchers and people living with dementia recommend developing new outcome measures that respond to the changing emphasis of dementia research and services towards the possibility of ‘living as well as possible’ with the condition [2], echoing global and national policies [3,4,5]. The European working group [2] acknowledge the value of constructs such as resilience for outcome measurement to counter the focus on deficit and disease. In response to debates around how to best define resilience, a systematic review and concept analysis of over 270 published articles defines resilience as “the process of effectively negotiating, adapting to, or managing significant sources of stress or trauma. Assets and resources within the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation and ‘bouncing back’ in the face of adversity” [6]. These essential features are corroborated by a recent systematic review of resilience in older people [7]. This ability to ‘do okay’ and achieve good outcomes despite major challenges and stressors is reflected in the growing global interest in healthy ageing [8] and supporting dementia carers [9,10,11]. Countering the focus on deficit sees emerging research highlighting how people with dementia can ‘live well’ despite the challenges of their dementia [12]. In other words, they are resilient.

Given the interest in resilience, researchers and practitioners may wish to use a resilience outcome measure in evaluation. To ensure data quality, outcome measures require considerable psychometric evaluation, demonstrating they accurately reflect underlying theory and concept, are well-accepted by responders, and accurately measure what they aim to do, in the target population of interest [1]. A number of resilience measures are available for different populations, and their psychometric properties have been systematically reviewed and appraised [13]. Fifteen measures were identified, most (N = 10) were developed for application with children and younger populations. None of the measures were developed with, and/or for, people living with dementia or their carer. Most of the resilience measures focus on resilience at the level of the individual only. A strong sense of personal agency may be important for negotiating adversity, but the availability of resources from the wider social environment is also important [13] as captured in recent developments in conceptualising resilience [6].

Another review [14] examined the psychometric properties of six resilience measurement scales in studies which sought to validate the measures in older populations, but none of the studies included people living with dementia or their caregivers. Consequently, it is currently difficult for resilience measures to be considered as one of the set of ‘core outcomes’ which are necessary to reduce the variation and inconsistency in the application of outcome measures in dementia research [15, 16].

Researchers and practitioners are often compelled to make pragmatic decisions regarding the choice of measurement scale, especially as considerable skill and resources are required for developing new outcome measures. Assessors may draw on existing measures originally designed for other populations and use a range of criteria to judge the potential usefulness of the scale, such as previous reports of a scale’s psychometric properties [1]. However, the demographic and circumstantial differences between people living with dementia or their carers, and the population in which the original measure was developed may influence the interpretation, meaning, validity and reliability of the original measure. Psychometric studies are required in order to ascertain whether a measure captures the intended construct (e.g. resilience) in a study sample that may differ from the original scale development sample [17]. The psychometric evaluation of measures is an important area for further investigation if we are to understand how the resilience of people living with dementia and those who support them can be enhanced by health, psychological and social care services or interventions.

A systematic review of positive psychology outcome measures for family caregivers of people living with dementia identified only one study using an existing resilience measure [18]. Stoner and colleagues [19] adapted the wording of the items of a ten-item resilience measure (the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale), removed two of the items and merged them with an adapted and reduced measure of ‘Hope’ to produce the ‘Positive Psychology Outcome Measure.’ This new measure shows promise for application in populations living with dementia, although the authors did not assess the psychometric properties of the 10-item resilience measure but chose it based on their earlier assessment of the larger 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale [20]. Consequently, the relevance and appropriateness of existing resilience measures may be inadequate for people living with dementia and their carers and require further investigation.

In response, the present study seeks to contribute new knowledge for research and practice regarding the measurement of resilience. The first aim is to systematically review the literature to identify studies that have administered an established resilience measurement scale with a) people living with dementia and/or b) their carers/supporters (not professional care providers). Identifying existing measurement scales, evaluating their, psychometric properties and possible appropriateness for future adaptation for use in the target population of interest is recommended as a first step in the development of a new measure, should this be required [1]. This leads to our second aim; to examine the psychometric properties of the resilience measures applied in these two populations. We use an established checklist [21] and adapt it to appraise the strengths, weaknesses and usefulness, in order to draw conclusions regarding the measures as applied in these two populations. We discuss the implications of our findings for research and practice.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic review protocol was developed and registered with PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ registration number CRD42021268316). The searches were initially scoped by the lead author and conducted by two people across the Web of Science (provides wide coverage Science Citation, Arts and Humanities Indexes and Social Sciences Citation), PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and ASSIA databases. These were selected so as to enable a comprehensive search beyond the minimum of two databases required to meet critical appraisal standards [22] to source peer-reviewed articles across a wide range of disciplines, e.g. sociology, psychology, health and medicine. Searches were conducted between 22.5.19 and 10.6.19, and updated 5.5.22 using two distinct search arms, combined with the Boolean term ‘AND’ to identify articles. (‘Resilience Or resilient OR resiliency AND Dementia OR Dementia OR Dementia's OR dementias OR demented OR Alzheimer OR Alzheimer's OR Alzheimers OR "posterior cortical atrophy" OR (Benson* AND syndrome) OR "primary progressive aphasia" OR "visual variant"). No date restrictions were applied. To identify further studies, an email was circulated around the INTERDEMFootnote 1 network (May 2019) calling for researchers to contact the lead author if using a measure of resilience. Reference lists of relevant articles were also searched. Experts in resilience recommended further articles as part of the 2022 updated search. All search results were exported into Mendeley and duplicates removed. The original development papers for each of the resilience measures were retrieved by GW.

Eligibility criteria

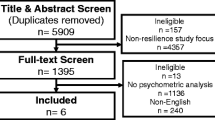

The titles and abstracts were initially screened by CW and SCu (see acknowledgements). Papers were included if they were an original peer reviewed research/journal article; the sample population was either a person living with dementia or a carer/supporter (family member, friend etc., often described as ‘informal’ carers) and the study used a resilience measurement scale. Papers were excluded if they were an ineligible article type (e.g. conference proceeding, report, book chapter, dissertation); were published in a language other than English; reported qualitative resilience outcomes or were focussed on professional care providers. Disagreements concerning inclusion/exclusion were resolved via a discussion with the lead author. At full-text screening reasons for exclusion were noted. The review process is outlined in Fig. 1.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted into an EXCEL file, with a worksheet for each of the identified resilience measures. This included information on the study characteristics (sample demographics, purpose of study, country, language, mode of data collection, psychometric data). Psychometric data were appraised using an 18-item checklist with six evaluative domains [21]. This checklist was developed to reflect the main evaluative properties recommended by the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments group (COSMIN) [23] and simplified in response to the complexity and length of the COSMIN checklist. See Table 1.

Two authors (GW and KA-S) initially piloted the data extraction, independently reviewing the same two papers. Checklist items regarding content validity relate to the development of the original measure, so the review team agreed to extract any information regarding adaptations to the measures for the population of interest (dementia caregivers and people living with dementia). Two authors (KA-S and CM) then reviewed and extracted data into EXCEL from 51 papers identified during screening meeting the eligibility criteria, regularly discussing and refining assessment criteria throughout the process. This was further reviewed and checked by GW.

The authors of the checklist [21] recommend scoring each item as either ‘0’criterion not met, or ‘1’criterion met.A number of additional data extraction points and a 0.5 score for some items were developed by the current authors to aid the scoring of papers whose focus was not developing a resilience measure, but using existing measures in their research (see Table 1 for checklist, additional points, and scoring adaptations. See Additional File 1 for further description). We include the hypotheses and/or study aims of the included papers to guide the psychometric data extraction. Although not proposed by Francis et al., we established additional evaluative indicators to indicate the strength of the relationship between two measures using Cohen’s criteria [24] where large correlations are > 0.50, medium correlations range between 0.30–0.49 and small correlations range between 0.10–0.29. This additional criteria does not influence the assessment score but is included to facilitate interpretation. Disagreements concerning scoring were resolved via a discussion between GW, KA-S and CM, with the final decision made by the lead author.

We draw on the previous methodological reviews of resilience measures in all populations [13] and resilience measurement in later life [14] to describe the development and psychometric evaluation of the original measures used by the studies in this review. Both the previous reviews addressed the psychometric robustness of resilience measures; Windle and colleagues [13] used a published quality assessment criteria with a scale ranging from 0–18 [25], with the included measures receiving scores ranging from 2–7, concluding that all the measures showed promise but further psychometric evaluation was required, especially in relation to responsiveness. Cosco and colleagues [14] specified the psychometric criteria established from their included studies (e.g. internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, construct validity).

Results and discussion

Study characteristics

Fifty-one studies were included in the final review [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], which applied nine different resilience measures. The review process is documented in Fig. 1. Table 2 describes the characteristics of the included studies and data relating to psychometric properties of the measures (e.g. internal consistency; construct validity; responsiveness). Two studies [42, 66] each report on two different measures so data for each measure is presented separately in Table 2, generating a total of 53 psychometric assessments. The majority of the studies focussed on carers (n = 47), three studies focused on people living with dementia, and one study [45] focussed on the dyad (people with dementia and their carers). One study [48] sought to adapt and evaluate the psychometric properties of positive psychology measures (which included a resilience measure, the RS-14) for people living with dementia. Another developed a measure of resilience for carers in Thailand [72]. The remaining studies applied an existing resilience measure (developed in other populations) in their research.

Description of the resilience measures

Resilience scale (RS)

The RS [77] aims to measure the degree of individual resilience (considered a positive personality characteristic) that enhances individual adaptation. The target group is adults. The scale has two dimensions (personal competence and acceptance of self and life) measured by twenty-five positively worded items, each scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total scores range from 25 to 175 with higher scores indicating higher resilience. Specifically scores greater than 145 indicate moderately high-to-high resilience, scores from 116 to 144 indicate moderately low- to-moderate levels of resilience, and scores of 115 and below indicate very low resilience [78]. Further clarification regarding the interpretation of scores, and suggestions for (self) improvement are provided by the authors and correspond with the following scoring ranges; 25–100 = very low, 101–115 = low, 116–130 = on the low end, 131–145 = moderate, 146–160 = moderately high, 161–175 = high [49]. The items were developed from qualitative research with 24 older women who successfully overcame a major life event. The target group were not involved in the item selection. The Resilience Scale is written at the 6th grade level (12–13 years) and it is suggested completion takes about 5–7 min by most people. The scale has been widely applied across different age and patient groups, translated into other languages and demonstrated reliability and validity [78], and has a dedicated website where users can register and receive a copy of the measure (for a fee), plus detailed information regarding its development and application, how to score and interpret it. Cosco et al. [14] included two studies using this measure in older populations, reporting high internal consistency (α = 0.85 and α = 0.91). Windle et al. [13] scored this scale 6/18 in their quality assessment (the measure lacked data in relation to test–retest at that time). Both authors suggest the RS as a suitable measure for older adults, with the RS suggested by Cosco et al. as having the strongest evidence in older populations. Twelve studies in this review used the RS with caregivers (see Table 2).

Brief resilience scale (BRS)

The BRS [79] aims to measure the ability to bounce back or recover from stress. The target group is adults. The scale has six items, scored on 5-point scale (total score range 6–30). The scale can be interpreted as low resilience (1–2.99), normal resilience (3–4.30), high resilience (4.31–5). The items were developed by the authors and refined through feedback from undergraduate students. Some of the target group (students) were involved in the item selection. Windle et al. [13] scored this scale 7/18 in their quality assessment. As the measure had evidence of test–retest, Windle et al. suggest the BRS could be useful for assessing change in response to an intervention. Ten studies in this review used the BRS with caregivers and one study [45] used the BRS with dyads (people with dementia and carers) (See Table 2). The scale is freely available for use and users should correctly cite and acknowledge the authors. The items and scoring are presented in the development papers.

Resilience scale-14 (RS-14)

The RS-14 is a shortened version of the original RS. The 14-items derived from the RS are scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) the same as the original RS. The total score ranges from 14 to 98 with higher scores indicating higher resilience. Specifically, scores greater than 90 in the RS-14 indicate high resilience, scores from 65 to 81 indicate moderately-low to moderate resilience, and scores of 64 and below indicate low resilience [78]. Further narrative interpretation and suggestions for (self) improvement are provided and correspond with the following scoring ranges; 14–56 = very low, 57–64 = low, 65–73 = on the low end, 74–81 = moderate, 82–90 = moderately high, 91–98 = high. The RS-14 is not comprised of any sub-scales. The original Resilience Scale and the RS-14 are strongly correlated (r = 0.97, p > 0.001 [78] and the measure is included in a dedicated website with the RS, where users can register and receive a copy of the measure (for a fee), plus detailed information regarding its development and application, how to score and interpret it. As a more recent development, no published studies using the RS-14 were identified in the reviews of Windle et al. [13] or Cosco et al. [13]. Five studies in this review used the RS-14 with caregivers and two studies used it with people living with dementia (see Table 2).

Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

The CD-RISC [80] aims to provide a self-rated assessment of resilience and a clinical measure to assess treatment response. The target group is adults. The scale has twenty-five items with no sub-scales, scored on a 5-point scale (total score range 0–100). The items were developed by the authors, derived from themes identified in a literature review, and the target group were not involved in the item selection. The scale has been widely applied across different age and patient groups, and translated into other languages, with a dedicated website about the development of the measure. Potential users are first required to register. The CD-RISC scored 7/18 in the review of Windle et al. [13]and was the only measure with data regarding responsiveness. Cosco et al. [14] concluded the CD-RISC potentially demonstrates sufficiently acceptable psychometric properties in older populations, although more psychometric evaluation studies are required. Seven studies in this review used the CD-RISC with caregivers (Table 2).

Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC 10)

The CD-RISC 10 [81] is a shortened version of the CD-RISC, being a single factor measure derived from a factor analysis of the full scale. The 10-items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time). The target group are adults and the measure was derived from data provided by 1,743 undergraduates from San Diego State University (SDSU) who completed questionnaires for course credit in 2004–2005. Most of these were female (74.4%) and the mean age was 18.8 years (SD = 2.2).

Cosco et al. [14] concluded the CD-RISC potentially demonstrates sufficiently acceptable psychometric properties in older populations, although more psychometric evaluation studies are required. Three studies in this review used the CD-RISC 10 with caregivers (Table 2).

Dispositional resilience scale (DRS)

The DRS [82] aims to measure psychological hardiness and is an adaptation of an earlier measure of personality hardiness. The target group is adults. The scale has three sub-scales (commitment, control and challenge), with the full scale measured by 45-items, scored on a 4-point scale (total score range 0–135). No information is provided as to whether the target group were involved in the item selection. The DRS scored 4/18 in the review of Windle et al. [13]. One study in this review used the DRS with caregivers. The scale is not widely used, but appears to be in the public domain.

Resilience scale for adults (RSA)

The RSA [83] aims to measure the protective resources that promote adult resilience and facilitate psychosocial adaptation to adversities. The scale has five dimensions (personal competence, social competence, family coherence, social support and personal structure) measured by 37 items, scored on a 5-point scale. Subsequent investigation reduced the questionnaire to 33 items scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 33–231, and suggest the factor ‘personal competence’ might contain two factors ‘perception of self’ and ‘planned future’ [84]. It is unclear if the target population were involved in the item selection. The RSA scored 7/18 in the review by Windle et al. [13], with the measure demonstrating evidence of test–retest stability. Eight studies in this review used the RSA with caregivers. Users are advised to contact the authors for permission to use the scale, and it has been translated into a number of languages.

Brief resilient coping scale (BRCS)

The BRCS [85] aims to measure resilient adaptive-coping behaviours in adults dealing with current stressors. The target group in scale development was people with Rheumatoid Arthritis. The scale has four items, scored on a 5-point scale (range 4–20). These can be interpreted as low resilient copers (4–13 score), medium resilient copers (14–16 score) and high resilient copers (17–20). The items were initially developed by the author and refined through consultation with six student nurses, the target group were not involved in the item selection. Cosco et al. [14] found one study examining the psychometric properties of the BRCS in an older Spanish population. They report the scale has good reliability and confirmatory factor analysis supported a one-factor structure, but the authors suggest further psychometric evaluation is required across other criteria. The scale is freely available for use and users should correctly cite and acknowledge the authors. The items and scoring are presented in the development papers. Three studies in this review use the BRCS, two with caregivers, and another comparing healthy older adults, adults with MCI and Alzheimer’s Disease (see Table 2).

Caregiver resilience scale (CRS—identified in the review process)

The caregiver resilience scale was developed for Thai caregivers of older people living with dementia [72]. The scale has six dimensions of competence (physical, relationship, emotional, moral, cognitive, spiritual), measured by 30 items scored on a 4-point scale (total score range 0–30). The authors note the domains of the measure were identified through a concept analysis, although this work is not presented or the article cited in their paper. They state qualitative interviews were undertaken with 10 carers to ‘confirm’ the domains suggested by the concept analysis, but the analysis and results are not presented and they do not appear to be reported in another article. Further information is presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Psychometric assessment

To facilitate evaluation of the nine resilience measures, Additional File 2 synthesises the psychometric assessment for each study into a narrative summary for each resilience measure across the six domains of the scoring criteria, which are discussed below The individual scores for each studyfollowing assessment against the six domains of the scoring criteria are presented in Table 3.

Conceptual model

Most of the studies defined the target population of their studies and briefly defined the construct to be measured (resilience), with a wide range of definitions used but did not expand on the theoretical basis of resilience. With the exception of the eight studies using the RSA, the extent to which resilience was conceptualised as a single construct/scale or a multiple construct/subscales was not addressed. This is a particular issue for further attention in the CRS [72], which has been developed for dementia carers. The conceptual model is especially important in the development of measures, where the theoretical underpinnings should be hypothesised. There is a growing literature suggesting what might constitute resilience in dementia caregivers (e.g. [9,10,11]) who indicate that social, psychological/individual and structural aspects are important. This then raises the question as to whether existing measures of resilience adequately reflect the theoretical underpinnings in this population, especially as Windle et al. [13] found that most resilience measures focus mainly on the individual/psychological aspects of resilience. Exploratory work with people living with dementia suggests the conceptualisation of resilience as ‘bouncing back’ from adversity, reflected in some resilience measures, may not be appropriate when living with a degenerative condition [86]. Other exploratory research notes that ‘growth’ was mentioned by several dementia carers when explaining why they considered themselves resilient, however there is debate in the literature regarding whether definitions of resilience should include concepts such as ‘growth’ or ‘thriving’ [87]. Further theoretical work with both populations exploring what resilience means to them would usefully contribute to the developing conceptual basis of resilience, and the extent to which existing measures are conceptually appropriate.

Content validity

The domain ‘content validity’ builds on the conceptual model to address the extent to which the questions and any sub-scales reflect the perspectives of the target group, and should involve the target group and content experts in their development [21]. Most of the studies scored poorly on this domain as they had applied an existing resilience measure developed in a different population in their studies, and the assessment items are primarily designed for measurement development. In terms of the original development of the measures identified in this review, only the RS involved the target group (older people) in its original development, which would also extend to the shorter RS-14.

Two studies in this review, one with carers [52] and another with people living with dementia [48] attended to the content validity of the RS-14, where adaptations are reported in response to the pilot work with the new target groups. The adaptations reported by McGee et al. [48] are potentially helpful for difficulties with comprehension and communication. Another reported how they used forward-back translation to translate the RSA into Spanish and obtained further feedback for any additional modifications by researchers familiar with the regional language and culture in Argentina [68].

Adapting existing measures is potentially efficient and pragmatic but requires careful consideration. The conceptual model of a measure for the target population should be relevant. Simplifying questions and response scales could potentially mean the measure is now a different tool, no longer comparable with the original. Some measures are subject to copyright, and the developers may not support adaptations. Researchers are encouraged to engage with the developers of the original measures from the outset should they wish to undertake adaptations.

The CRS provided evidence of content validity for two of the three assessment items, indicating 10 caregivers were asked to confirm the pre-specified structure of caregivers’ resilience as relevant to Thai caregivers, and three experts were consulted on the content validity [72]. No data is presented to support this process nor any information about how the items were initially generated. The conceptual basis of this measure requires further explanation. Given the theoretical issues described in the previous section, the extent to which the resilience measures are relevant and comprehensively represent resilience in these two populations requires further investigation.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the measures was assessed under the domain ‘reliability’. Nineteen studies across seven measures provided this data from their study populations, with no data relating to internal consistency for the CD-RISC, and the DRS. Some studies cited the internal consistency of the original development study. Additional File 2 summarises how many studies report this data for each of the nine measures. Where reported, the available data note internal consistency in the ‘ideal’ and ‘adequate to ideal’ range for the measures in carers, in one study for the RS-14 in people with dementia [48] and in another for the BRCS across a mixed sample of healthy older adults, people with MCI and Alzheimer’s Disease [71]. One study [39] reported low internal consistency for the BRS in carers out of the three that provided the data for this measure. When measures are applied in a different population to the one previously developed such as those identified in this review, as a minimum we encourage authors to report the internal consistency of the measure. Reporting reliability scores of original measures are insufficient if using a measure with a new population.

Construct validity

The conceptual aspect also has implications for the domain of ‘construct validity’, which reflects the extent to which a scale measures the construct of resilience. Most of the studies in this review provided some data for this domain, mainly around associations with other existing outcome measures or demographic data, and we used Cohen’s criteria [24] to indicate the size of effect and consequent strength of the relationship (Table 2). Twenty-eight studies hypothesised effects (associations with other outcome measures or demographic data, or differences in scores between relevant groups). These were partially supported. The others were either exploratory or did not specify hypotheses. The assessment of construct validity required authors to state hypotheses regarding expected correlations, differences and the magnitude of these apriori, consequently, it is unclear what some authors were expecting to find from their analyses. For example, McGee et al. [48] state they test the convergent validity of their positive psychology measures, and the discriminant validity between the positive psychology measures, depression and anxiety, but do not hypothesise whether they expect a positive or negative relationship, or no relationship (which would be expected for discriminant validity).

Nine studies had a longitudinal aspect to their study design. Four hypothesised change in response to an intervention, with some evidence for the RSA and CRS in carers [65], an RCT found no effects of an intervention on the RS-14 in carers [49], and another reported improvements over time in the CD-RISC for carers but the data is not presented to support this claim [54]. There was partial support from a longitudinal cohort study for the DRS in carers [61]. Three did not specify hypotheses, but report improvements in the RS for carers in a grief coaching intervention [31], improvements in the CD-RISC 10 for carers in a grief intervention [59] and no difference in the BRS for carers in an arts intervention [40]. Test–retest data is required for the measures in these populations to help evidence stability of the measures when no change is anticipated. This will help confirm any changes found in response to an intervention are not random but an effect of the intervention.

Some studies are also likely to have been insufficiently powered to detect small effects which could provide support for construct validity. For example, with a power of 0.80 (β = 0.20) and α of 0.05 a sample of 85 participants is needed to detect a small-medium sized correlation of r = 0.3 [88]. To illustrate, Kimura et al. [29] did not find hypothesised associations between carers resilience and clinical characteristics of the care recipient but reported significant correlations between carer resilience and carer indicators of mental health. All correlations with resilience reported in this study, with the exception of the carer’s depression score (r = -0.405), had effect sizes below 0.35 which the study sample size (n = 43) was too small to detect using standard α = 0.05, β = 0.20 parameters. The insufficient powering of this study therefore reduces the likelihood that the statistically significant results showing associations between resilience and anxiety, and resilience and hopelessness reflect true effects, and may also mean that failure to find significant hypothesised relationships between resilience and other measures could be false negatives reflecting small sample size. Studies with small sample sizes therefore need to be interpreted with caution, and study sample size should be considered when weighing evidence in the evaluation of measure validity. Future research should aim to clarify how resilience is expected to influence outcomes through establishing hypotheses, derived from a sound theoretical basis, and should ensure that studies are sufficiently powered to detect expected effects.

Scoring and interpretation

Most of the studies lacked information on how the total score for the measure used was derived (although this should be available in the original measure development papers) and how missing data was dealt with. There were some inconsistencies between the original development papers and the studies in this review in descriptions of cut-points. Kimura et al. [30] describe cut points of the RS measure in their study that indicate low, medium and high resilience, but these do not correspond with the suggested cut points of the original measure. The mean score (5.50) for the RS reported by Fitzpatrick and Vacha-Hasse [28] does not appear to reflect the scoring range as proposed by the developers, and it is unclear how this score was derived. Vatter et al. report data according to low (1–2.99) and high (3–5) BRS scores, but these categories are different to those specified by the scale developers who note low resilience (1–2.99), normal resilience (3–4.30), high resilience (4.31–5). There was also some lack of clarity regarding whether the original measure had been correctly administered, e.g. Sutter et al. [42] indicate using a 36-item version of the RSA, but further on state they removed seven items from a larger, 45-item scale. Lack of detail regarding changes to the scoring also featured. Stansfield [51] note the scoring of the RS-14 items as ranging between 1 (Strongly disagree) and 6 (strongly agree), with possible sores ranging from 14 to 84. This is different to the original measure, but no adaptations are described. McGee [48] note they adapted the RS-14 to a 3-point Likert scale (disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree) from the original 7-point scale, but no information is provided regarding the scale range and how it was scored.

Future studies should ensure they are using the measure as recommended by the developers, and fully report any adaptations they make to aid interpretation and for future use by others.

Respondent burden and presentation

This domain had limited information on time to complete the measure, with only one study, Bull [26], indicating the RS took 5–10 min to complete. None alluded to the literacy level of the original measure. Although these items are likely of more relevance to developers of new measures, when applied in new populations who may have different education and literacy levels than the populations the measure was developed for, this information would be useful to record, as any difficulties could invalidate the measure. One study provided the full measure in their paper [72]. The other measures are either available freely from the developers or for a fee.

Implications of the results for research and practice

Identifying existing measures and examining the extent to which they are appropriate for use in a different population is a recommended first step in measurement development, to avoid the considerable time required for the development of a new measure [1]. This requires the validity and reliability to be established in the new population. Only one study explicitly set out to explore the validity of the RS-14, presenting some limited evidence of convergent validity without clear hypotheses [48]. Most of the papers presented a limited amount of relevant data for our assessment, highlighting areas to consider regarding the conceptualisation of resilience and the future application and development of resilience measures in these populations.

Based on this review, it is difficult to make firm recommendations regarding which measure may be most appropriate, and users should consider the context in which they wish to use it. We make some suggestions, recognising that people need to make pragmatic choices for research and practice regarding outcome measures. Where reported, the internal consistency was graded ‘adequate to ideal’ in all the measures except for one study [39]. Additional File 2 summarises how many studies report this data for each measure. Most of these are applied with carers, and the (limited) data suggests the RS, BRS, RS-14, RSA, CD-RISC 10 and CRS are reliably assessing the target construct in carers, and the RS-14 and the BRCS in people with dementia.

The evidence for construct validity was mixed, and for studies with hypotheses, there were mixed results regarding the effects, but these provide a useful starting point for validating in future studies. For example, there is some suggestion the resilience measures were associated with measures of depression, anxiety, burden and quality of life across the studies, with effects ranging from small to large.

For those wishing to measure the impact of services and interventions, evidence of responsiveness to the effects of an intervention was limited in this review as most of the studies were cross sectional. Of the studies that hypothesised change over time in response to an intervention, there was evidence from one study each for the RSA and the CRS.

This is an important area for further development, especially for researchers and practitioners who wish to measure changes in resilience in response to interventions and services.

As service evaluations often assess multiple outcomes, it may be prudent to consider efforts to minimise respondent burden by selecting a shorter resilience measure. The RS-14, a widely applied measure in general research and the short version of the RS was used in sixstudies with people living with dementia, providing some (albeit limited) evidence of construct validity. The BRS may also be a useful option with carers, but the focus on bouncing back raise questions regarding how appropriate this measure would be for people living with dementia. The RSA and the CD-RISC were viewed as the more psychometrically robust tools in the measures reviews of Cosco et al. [14] and Windle et al. [13], but evidence of their psychometric properties was lower in this present review. This may be due to the application of a different quality assessment criteria, but is more likely due to the included studies not reporting data relevant for psychometric assessment.Whatever the choice, this review calls for researchers and practitioners to report psychometric data to advance the field. For those with an interest in the field of positive psychology, the Positive Psychology Outcome Measure (PPOM) is validated for use in people living with dementia and may be especially useful for intervention studies [89].

A broader consideration is that dementia is a progressive disease affecting cognitive functioning, which presents challenges when developing and administering outcome measures. Elsewhere, researchers have demonstrated that people in the milder to moderate stages of the condition are capable of providing reliable responses on widely used outcome measures [e.g. [90, 91] and should be given the opportunity to provide their opinions. As with all degenerative conditions, there will be a point when psychometric assessment may not be possible. At this point, proxy measures which enable another person to provide responses on behalf of a person living with dementia are one option to overcome this, yet none of the resilience measures in the review have a proxy version available. The extent to which people with dementia may be unaware of difficulties or changes they are experiencing may influence reporting outcomes. Other research suggests that people with dementia who focussed less on memory problems, perhaps appearing less aware of difficulties, also reported better well-being and mood [92]. Although this effect may be interpreted as a form of positive response bias, it may also be viewed as an adaptive form of coping in some situations, focusing on strengths rather than problems [93].

Researchers and practitioners may also need to consider the specific type of dementia a person is living with, and whether simple adaptations in the administration of a measure may be required to best support a person with different clinical presentations. Working with the target groups in any adaptations or development of new measures will help ensure questions are appropriate and understandable.

Strengths and weaknesses of this review

Following piloting of the checklist [21], additional criteria were developed to assist in applying the checklist to studies that used an existing resilience measure, such as those identified in this review. Unfortunately, the scoring of the included studies was hindered by the absence of psychometric information in some of the studies, and in this respect, scores reflect how well publications report psychometric information. This also does not necessarily mean the resilience measure is not suitable, and we encourage future users of resilience measures in these populations to report information to advance knowledge and inform further reviews. Given the number of studies identified it was beyond the resources and the timescale of this work to contact individual authors for further information.

The checklist could also be considered overly stringent. For example, a checklist item under the ‘conceptual model’ domain requires studies to state whether a single scale or multiple sub-scales are expected. Whilst a number of studies noted the number of items in the measure they applied, they did not explicitly state whether it was a single-scale or had sub-scales. The domain of ‘respondent burden and presentation’ reflects the time taken to complete and the complexity of a measure, and the extent to which a measure is in the public domain. With the exception of one study using the RS which reported completion time, it was not possible to ascertain this information. We suggest this domain is more relevant to measurement development than the application to studies using a measure, as this information is not usually included in primary research, and when included often refers to total study time rather than individual measures. However, few checklists are available and the application of the checklist in this review enabled a systematic psychometric assessment of the resilience measures in these populations.

We did not include ‘cognitive impairment’ (nor any truncations/derivatives) in the search terms. This was due to the phrase capturing literature on cognitive impairment relating not only to dementia, but also other neurological conditions such as stroke and/or learning difficulties, which remain outside the scope of the current review. We note however that including Alzheimer’s Disease and other variations would enrich the breadth of papers and extended our clinical population search terms to incorporate Alzheimer’s Disease (including rarer variants such as Posterior Cortical Atrophy).

Conclusions

This study systematically identified nine resilience measures applied in 51 studies examining the resilience of people living with dementia and their carers. We critically reviewed the measurement properties and applicability from the available psychometric data using a standardised checklist adapted for purpose. To our knowledge, no previous study has undertaken this research and our work contributes important new findings.

Notably most of the studies (N = 43) were cross-sectional designs and most studies used resilience measures with dementia carers (N = 47). All the identified measures require further psychometric evaluation in both these populations, and we encourage researchers to report relevant data in their publications to help advance the evidence base. With the exception of the CRS (which requires further psychometric evaluation) the measures were not developed with, and for dementia carers and would benefit from further investigation so as to support their use in future research and practice. This could ensure the existing measures comprehensively reflect their personal experiences of resilience, together with the growing conceptual understanding of resilience in this population.

Only three studies measured the resilience of people living with dementia, with one study measuring the resilience of both carers and the person with dementia. Further research to understand the experience of resilience for people living with dementia is warranted. This could establish the extent these experiences are reflected in current measures in terms of the underpinning conceptual model, whether existing measures could be adapted and updated and whether a proxy version could be developed. Further work to establish a new measure may need to consider measuring resilience beyond the individual and include their families and communities as sources of resilience, reflecting contemporary thinking in international policy which recognises that resilience can be strengthened at three levels: individual, community and system/society [94] as corroborated in a systematic review examining the conceptual basis of resilience [6]. Practitioners might be served to consider these broader conceptual aspects of resilience in assessing and formulating support for this population. People living with dementia and carers should be central to any measurement development or adaptation, in order to embed their lived experiences.

Availability of data and materials

This article was derived from secondary sources (published research articles) which are cited in the reference list. No primary data is included. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Notes

Early detection and timely INTERvention in Dementia.

References

Streiner, D.L., Norman, G.R., Cairney, J., 2015. Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use, fifth ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199685219.001.0001.

JPND Working Group on Longitudinal Cohorts, 2015. Dementia Outcome Measures: Charting New Territory. https://www.neurodegenerationresearch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/JPND-Report-Fountain.pdf

Department of Health, 2009. Living well with dementia: A National Dementia Strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/168220/dh_094051.pdf

World Health Organisation and Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012. Dementia: A Public Health Priority. Accessed from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/.

Welsh Government, 2018. Dementia Action Plan for Wales 2018–2022. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-04/dementia-action-plan-for-wales.pdf.

Windle G. What is resilience? a review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;21(2):152–69.

Angevaare MJ, Roberts J, van Hout H, Joling KJ, Smalbrugge M, Schoonmade LJ, Windle G, Hertogh C. Resilience in older persons: a systematic review of the conceptual literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;63: 101144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101144.

World Health Organisation, 2015. World Report on Ageing and Health. Accessed from: https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/.

Cherry MG, Salmon JM, Dickson JM, Powell D, Sikdar S, Ablett J. Factors influencing the resilience of carers of individuals with dementia. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2013;23:251–66.

Joling KJ, Windle G, Dröes RM, Meiland F, van Hout HP, MacNeil Vroomen J, van de Ven PM, Moniz-Cook E, Woods B. Factors of resilience in informal caregivers of people with dementia from integrative international data analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2016;42(3–4):198–214. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449131.

Teahan Á, Lafferty A, McAuliffe E, Phelan A, O’Sullivan L, O’Shea D, Fealy G. Resilience in family caregiving for people with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1582–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4972 (Epub 2018 Sep 19 PMID: 30230018).

Lamont, R.A., Nelis, S.M., Quinn, C., Martyr, A., Rippon, I., Kopelman, M.D., Hindle, J.V., Jones, R.W., Litherland, R., Clare, L., on behalf of the IDEAL study team. 2020 Psychological predictors of 'living well' with dementia: findings from the IDEAL study Aging Ment Health 24 956 964 https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1566811

Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-8.

Cosco TD, Kaushal A, Richards M, Kuh D, Stafford M. Resilience measurement in later life: a systematic review and psychometric analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0418-6.

Harding AJE, Morbey H, Ahmed F, Opdebeeck C, Ying-Ying W, Williamson P, Swarbrick C, Leroi I, Challis D, Davies L, Reeves D, Holland F, Hann M, Hellström I, Hydén L, Burns A, Keady J, Reilly S. Developing a core outcome set for people living with dementia at home in their neighbourhoods and communities: study protocol for use in the evaluation of non-pharmacological community-based health and social care interventions. Trials. 2018;19:247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2584-9.

Webster L, Groskreutz D, Grinbergs-Saull A, Howard R, O’Brien JT, Mountain G, Banerjee S, Woods B, Perneczky R, Lafortune L, Roberts C, McCleery J, Pickett J, Bunn F, Challis D, Charlesworth G, Featherstone K, Fox C, Goodman C, Jones R, Lamb S, Moniz-Cook E, Schneider J, Shepperd S, Surr C, Thompson-Coon J, Ballard C, Brayne C, Burns A, Clare L, Garrard P, Kehoe P, Passmore P, Holmes C, Maidment I, Robinson L, Livingston G. Core outcome measures for interventions to prevent or slow the progress of dementia for people living with mild to moderate dementia: Systematic review and consensus recommendations. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6): e0179521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179521.

Cosco TD, Kok A, Wister A, Howse K. Conceptualising and operationalising resilience in older adults. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2019;7:90–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2019.1593845.

Stansfeld J, Stoner C, Wenborn J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E, Orrell M. Positive psychology outcome measures for family caregivers of people living with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(8):1281–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000655.

Stoner CR, Orrell M, Long M, Csipke E, Spector A. The development and preliminary psychometric properties of two positive psychology outcome measures for people with dementia: the PPOM and the EID-Q. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0468-6.

Stoner CR, Orrell M, Spector A. Review of positive psychology outcome measures for chronic illness, traumatic brain injury and older adults: adaptability in dementia? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;40(5–6):340–57. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439044 (Epub 2015 Sep 25 PMID: 26401914).

Francis DO, McPheeters ML, Noud M, Penson DF, Feurer ID. Checklist to operationalize measurement characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0307-4.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358: j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9.

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012.

Bull MJ. Strategies for sustaining self used by family caregivers for older adults with dementia. J Holist Nurs. 2014;32(2):127–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010113509724.

Dias R, Simões-Neto JP, Santos RL, Sousa MFB, de Baptista MAT, Lacerda IB, et al. Caregivers’ resilience is independent from the clinical symptoms of dementia. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;74(12):967–73.

Fitzpatrick KE, Vacha-Haase T. Marital satisfaction and resilience in caregivers of spouses with dementia. Clin Gerontol. 2010;33(3):165–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317111003776547.

Kimura NRS, Neto JPS, Santos RL, Baptista MAT, Portugal G, Johannessen A, Barca ML, Engedal K, Laks J, Rodrigues VM, Dourado MCN. Resilience in carers of people with young-onset Alzheimer Disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2019;32(2):59–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988718824039.

Kimura NRS, Simoes JP, Santos RL, Baptista MAT, Portugal MD, Johannessen A, et al. Young- and late-onset dementia: a comparative study of quality of life, burden, and depressive symptoms in caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2021;34(5):434–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988720933355.

MacCourt P, McLennan M, Somers S, Krawczyk M. Effectiveness of a grief intervention for caregivers of people with dementia. Omega (Westport). 2017;75(3):230–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222816652802.

Monteiro AMF, Neto JPS, Santos RL, Kimura N, Baptista MAT, Dourado MCN. Factor analysis of the resilience scale for brazilian caregivers of people with alzheimer’s disease. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021;43(4):311–9. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0179.

Pessotti CFC, Fonseca LC, Tedrus, G.M.de A.S., Laloni, D.T. Family caregivers of elderly with dementia Relationship between religiosity, resilience, quality of life and burden. Dement Neuropsychol. 2018;12(4):408–14. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-040011.

Rosa, R.D.L.da., Simoes-Neto, J.P., Santos, R.L., Torres, B., Baptista, M.A.T., Kimura, N.R.S., Dourado, M.C.N. 2018 Caregivers’ resilience in mild and moderate alzheimer’s disease Aging Ment Health 24 2 250 258 https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1533520

Svanberg E, Stott J, Spector A. “Just helping”: Children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(6):740–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713174.

Canevelli M, Bersani FS, Sciancalepore F, Salzillo M, Cesari M, Tarsitani L, et al. Frailty in caregivers and its relationship with psychological stress and resilience: A cross-sectional study based on the deficit accumulation model. J Frailty Aging. 2022;11(1):59–66. https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2021.29.

Carbone E, Palumbo R, Di Domenico A, Vettor S, Pavan G, Borella E. Caring for people with dementia under COVID-19 restrictions: a pilot study on family caregivers. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:652833.

Chan EWL, Yap PS, Khalaf ZF. Factors associated with high strain in caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in Malaysia. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40(4):380–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.12.009.

Kalaitzaki A, Koukouli S, Foukaki ME, Markakis G, Tziraki C. Dementia family carers’ quality of life and their perceptions about care-receivers’ dementia symptoms: the role of resilience. J Aging Health. 2022;34(4–5):581–90.

McManus K, Tao H, Jennelle PJ, Wheeler JC, Anderson GA. The effect of a performing arts intervention on caregivers of people with mild to moderately severe dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(4):735–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891200.

Prins M, Willemse B, van der Velden C, Pot AM, van der Roest H. Involvement, worries and loneliness of family caregivers of people with dementia during the COVID-19 visitor ban in long-term care facilities. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(6):1474–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.002.

Sutter M, Perrin PB, Peralta SV, Stolfi ME, Morelli E, Pena Obeso LA, Arango-Lasprilla JC. Beyond strain: Personal strengths and mental health of Mexican and Argentinean dementia caregivers. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(4):376–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615573081.

Vatter S, McDonald KR, Stanmore E, Clare L, Leroi I. Multidimensional care burden in Parkinson-related dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(6):319–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988718802104.

Vatter S, Stanmore E, Clare L, McDonald KR, McCormick SA, Leroi I. Care Burden and Mental Ill Health in Spouses of People With Parkinson Disease Dementia and Lewy Body Dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2019;33(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988719853043.

Vatter S, Leroi I. Resilience in people with Lewy body disorders and their care partners: Association with mental health, relationship satisfaction, and care burden. Brain Sci. 2022;12(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020148.

Wuttke-Linnemann A, Henrici CB, Müller N, Lieb K, Fellgiebel A. Bouncing back from the burden of dementia: Predictors of resilience from the perspective of the patient, the spousal caregiver, and the dyad - an exploratory study. GeroPsych (Bern). 2020;33(3):170–81. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000238.

D’Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Raciti M, Burke M, Teare A, Kovacic T, Cortis K, Murphy K, Barrett E, Whelan S, Dolan A, Russo A, Ricciardi F, Pegman G, Presutti V, Messervey T, Cavallo F, Giuliani F, Bleaden A, Casey D, Greco A. MARIO project: validation and evidence of service robots for older people with dementia. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;68(4):1587–601. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-181165.

McGee JS, Zhao HC, Myers DR, Kim SM. Positive psychological assessment and early-stage dementia. Clin Gerontol. 2017;40(4):307–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1305032.

Orgeta V, Leung P, Yates L, Kang S, Hoare Z, Henderson C, Whitaker C, Burns A, Knapp M, Leroi I, Moniz-Cook ED, Pearson S, Simpson S, Spector A, Roberts S, Russell IT, de Waal H, Woods RT, Orrell M. Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: a clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(64):1–108. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19640.

Sanchez-Teruel D, Robles-Bello M, Sarhani-Robles M, Sarhani-Robles A. Exploring resilience and well-being of family caregivers of people with dementia exposed to mandatory social isolation by COVID-19. Dementia (London). 2022;21(2):410–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211042187.

Stansfeld J, Orrell M, Vernooij-Dassen M, Wenborn J. Sense of coherence in family caregivers of people living with dementia: a mixed-methods psychometric evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1114-0.

Wilks SE, Spurlock WR, Brown SC, Teegen BC, Geiger JR. Examining spiritual support among African American and Caucasian Alzheimer’s caregivers: a risk and resilience study. Geriatr Nurs. 2018;39(6):663–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.05.002.

Duran-Gomez N, Guerrero-Martin J, Perez-Civantos D, Jurado CFL, Palonno-Looez P, Caceres MC. Understanding resilience factors among caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease in Spain. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:1011–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S274758.

Gomez-Trinidad M, Chimpen-Lopez C, Rodriguez-Santos L, Moral MA, Rodriguez-Mansilla J. Resilience, emotional intelligence, and occupational performance in family members who are the caretakers of patients with dementia in Spain: a cross-sectional, analytical, and descriptive study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4262.

Lavretsky H, Siddarth P, Irwin MR. Improving depression and enhancing resilience in family dementia caregivers: a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):154–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181beab1e.

Rivera-Navarro J, Sepúlveda R, Contador I, FernándezCalvo B, Ramos F, Tola-Arribas MÁ, et al. Detection of maltreatment of people with dementia in Spain: usefulness of the caregiver abuse screen (CASE). Eur J Ageing. 2018;15(1):87–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0427-2.

Ruisoto P, Contador I, Fernandez-Calvo B, Serra L, Jenaro C, Flores N, et al. Mediating effect of social support on the relationship between resilience and burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;86:103952.

Serra L, Contador I, Fernandez-Calvo B, Ruisoto P, Jenaro C, Flores N, Ramos F, Rivera-Navarro J. Resilience and social support as protective factors against abuse of patients with dementia: a study on family caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(8):1132–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4905.

Bravo-Benitez J, Cruz-Quintana F, Fernandez-Alcantara M, Perez-Marfil M. Intervention program to improve grief-related symptoms in caregivers of patients diagnosed with dementia. Front Psychol. 2021;12:628750.

Sarabia-Cobo C, Sarria E. Satisfaction with caregiving among informal caregivers of elderly people with dementia based on the salutogenic model of health. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;62: 151507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151507.

O’Rourke N, Kupferschmidt AL, Claxton A, Smith JZ, Chappell N, Beattie BL. Psychological resilience predicts depressive symptoms among spouses of persons with Alzheimer disease over time. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(8):984–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.501063.

Altieri M, Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(1):27–34.

AG Elnasseh MA Trujillo SV Peralta ME Stolfi E Morelli PB Perrin JC Arango-Lasprilla 2016 Family Dynamics and Personal Strengths among Dementia Caregivers in Argentina Int J Alzheimer's Dis 2386728 https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2386728

Gulin SL, Perrin PB, Peralta SV, McDonald SD, Stolfi ME, Morelli E, Peña A, Arango-Lasprilla JC. The Influence of personal strengths on quality of care in dementia caregivers from Latin America. J Rehabil. 2018;84(1):13–21.

Senturk SG, Akyol MA, Kucukguclu O. The relationship between caregiver burden and psychological resilience in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Int J Caring Sci. 2018;11(2):1223–30.

Pandya SP. Meditation program enhances self-efficacy and resilience of home-based caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer’s: A five-year follow-up study in two South Asian cities. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62(6):663–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2019.1642278.

SK Trapp PB Perrin R Aggarwal SV Peralta ME Stolfi E Morelli LAP Obeso JC Arango-Lasprilla 2015 Personal strengths and health related quality of life in dementia caregivers from Latin America Behav Neurol 507196 https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/507196

Trujillo MA, Perrin PB, Panyavin I, Peralta SV, Stolfi ME, Morelli E, et al. Mediation of family dynamics, personal strengths, and mental health in dementia caregivers. J Lat Psychol. 2016;4(1):1–17.

Jones SM, Killett A, Mioshi E. What factors predict family caregivers’ attendance at dementia cafes? J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64(4):1337–45. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180377.

Jones SM, Woodward M, Mioshi E. Social support and high resilient coping in carers of people with dementia. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40(6):584–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.05.011.

Meléndez JC, Satorres E, Redondo R, Escudero J, Pitarque A. Wellbeing, resilience, and coping: Are there differences between healthy older adults, adults with mild cognitive impairment, and adults with Alzheimer-type dementia? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;77:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.04.004.

Maneewat T, Lertmaharit S, Tangwongchai S. Development of caregiver resilience scale (CRS) for Thai caregivers of older persons with dementia. Cogent Med. 2016;3:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2016.1257409.

Garity J. Stress, learning style, resilience factors, and ways of coping in Alzheimer family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 1997;12(4):171–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331759701200405.

Scott CB. Alzheimer’s disease caregiver burden: does resilience matter? J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2013;23(8):879–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.803451.

Wilks SE, Little KG, Gough HR, Spurlock WJ. Alzheimer’s aggression: influences on caregiver coping and resilience. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2011;54(3):260–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2010.544531.

Wilks SE, Vonk ME. Private prayer among Alzheimer’s caregivers: mediating burden and resiliency. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;50(3–4):113–31. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v50n3_09.

Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1(2):165–78.

Wagnild G. The Resilience Scale user’s guide for the English US version of the Resilience Scale and the 14-Item Resilience Scale (RS-14). USA: The Resilience Center; 2009.

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271.

Bartone PT, Ursano RJ, Wright KM, Ingraham LH. The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(6):317–28.

Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(2):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.143.

Friborg O, Barlaug D, Martinussen M, Rosenvinge JH, Hjemdal O. Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14:29–40.

Sinclair VG, Wallston KA. The development and psychometric evaluation of the brief resilient coping scale. Assessment. 2004;11(1):94–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191103258144.

Windle, G., 2021. Resilience in Later Life: Responding to Criticisms and Applying New Knowledge to the Experience of Dementia, in: Wister, A.V., Cosco, T. (Eds.), Resilience and Aging: Emerging Science and Future Possibilities. Springer International Publishing.

O’Dwyer ST, Moyle W, Taylor T, Creese J, Zimmer-Gembeck M. In their own words: how family carers of people with dementia understand resilience. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030057.

Kohn, M.A., Senyak, J., 2021. Sample size calculators [Internet]. San Francisco: UCSF CTSI; 2021. [cited August 2021]. Available from: https://www.sample-size.net/

Stoner CR, Orrell M, Spector A. The positive psychology outcome measure (PPOM) for people with dementia: psychometric properties and factor structure. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;76:182–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.03.001.

Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood RH, Foley B, Smith P, Cook JC, Murray J, Prince M, Levin E, Mann A, Knapp M. Development of a new measure of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: DEMQOL. Psychol Med. 2007;37(5):737–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170600946.

Romhild J, Fleischer S, Meyer G, Stephan A, Zwakhalen S, Leino-Kilpi H, Zabalegui A, Saks K, Soto-Martin M, Sutcliffe C, Hallberg IR, Berg A. Inter-rater agreement of the quality of life-Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD) self rating and proxy rating scale: secondary analysis of RightTimePlaceCare data. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;6(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0959-y (Epub 2018/06/30).

Windle G, Hoare Z, Woods B, Huisman M, Burholt V. A longitudinal exploration of mental health resilience, cognitive impairment and loneliness. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(7):1020–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5504.

Clare L, Quinn C, Jones IR, Woods RT. “I Don’t think of it as an Illness”: Illness representations in mild to moderate dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(1):139–50.

World Health Organisation, 2017. Strengthening resilience: a priority shared by Health 2020 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Strengthening resilience: a priority shared by Health 2020 and the Sustainable Development Goals (who.int).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Siobhan Culley for her input into searching for the literature, to Iona Strom for formatting the reference list and to the reviewers for their valuable comments.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research Grant/Award Number: ES/S010467/1, funded as ‘The impact of multicomponent support groups for those living with rare dementias’. Lead investigator S. Crutch (University College London (UCL)); Co-investigators J. Stott, P. Camic (UCL); G. Windle, R. Tudor-Edwards, Z. Hoare (Bangor University); M.P. Sullivan (Nipissing University); R. Mackee-Jackson (National Brain Appeal).

ESRC is part of UK Research and Innovation. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the ESRC, UKRI, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding for the publishing of this paper was provided by Bangor University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GW: led the development of the paper, conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, project administration, acquisition of funding. CM: methodology, formal analysis, writing-review and editing, project administration. K-AS: methodology, formal analysis, writing-review and editing, project administration. JS: writing-review and editing, acquisition of funding. CW literature searching, review. PC: writing-review and editing, acquisition of funding. MPS: writing-review and editing, acquisition of funding. EB: writing-review and editing, acquisition of funding. SC: writing-review and editing, acquisition of funding. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Windle, G., MacLeod, C., Algar-Skaife, K. et al. A systematic review and psychometric evaluation of resilience measurement scales for people living with dementia and their carers. BMC Med Res Methodol 22, 298 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01747-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01747-x