Abstract

Background

Cistanche is an important genus of Orobanchaceae, with critical medicinal, economic, and desertification control values. However, the phylogenetic relationships of Cistanche genus remained obscure. To date, no effective molecular markers have been reported to discriminate effectively the Cistanche closely related species reported here. In this study, we obtained and characterized the plastomes of four Cistanche species from China, to clarify the phylogenetic relationship within the genus, and to develop molecular markers for species discrimination.

Results

Four Cistanche species (Cistanche deserticola, Cistanche salsa, Cistanche tubulosa and Cistanche sinensis), were deep-sequenced with Illumina. Their plastomes were assembled using SPAdes and annotated using CPGAVAS2. The plastic genomes were analyzed in detail, finding that all showed the conserved quadripartite structure (LSC-IR-SSC-IR) and with full sizes ranging from 75 to 111 Kbp. We observed a significant contraction of small single copy region (SSC, ranging from 0.4–29 Kbp) and expansion of inverted repeat region (IR, ranging from 6–30 Kbp), with C. deserticola and C. salsa showing the smallest SSCs with only one gene (rpl32). Compared with other Orobanchaceae species, Cistanche species showed extremely high rates of gene loss and pseudogenization, as reported for other parasitic Orobanchaceae species. Furthermore, analysis of sequence divergence on protein-coding genes showed the three genes (rpl22, clpP and ycf2) had undergone positive selection in the Cistanche species under study. In addition, by comparison of all available Cistanche plastomes we found 25 highly divergent intergenic spacer (IGS) regions that were used to predict two DNA barcode markers (Cis-mk01 and Cis-mk02 based on IGS region trnR-ACG-trnN-GUU) and eleven specific DNA barcode markers using Ecoprimer software. Experimental validation showed 100% species discrimination success rate with both type of markers.

Conclusion

Our findings have shown that Cistanche species are an ideal model to investigate the structure variation, gene loss and pseudogenization during the process of plastome evolution in parasitic species, providing new insights into the evolutionary relationships among the Cistanche species. In addition, the developed DNA barcodes markers allow the proper species identification, ensuring the effective and safe use of Cistanche species as medicinal products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cistanche species are a group of non-photosynthetic parasitic plants, belonging to the Orobanchaceae. The family contains nonparasitic, hemiparasitic as well as holoparasitic species [1]. The Orobanchaceae are an excellent model system for: a) the studying of plant parasitism evolution; b) the investigation of phenotypic plasticity [2, 3]. Cistanche species, as nonphotosynthetic holoparasites, are completely devoid of chlorophyll and functional leaves. They are remarkable in appearance, comprising imposing, brightly colored flowering spikes that sprout seemingly from bare earth, which has earned them their common name ‘desert hyacinths’ [4]. Some 20–30 accepted species known as the Old World constitute the genus Cistanche, which traverses from the west (Macaronesia) to the east (Northwest China) [4]. Cistanche species grow in deserts, and occasionally coastal dunes or salt marshes, where they are parasitic on the roots of various halophytic shrubs. Cistanche species are highly useful industrial cultivation plants resources for fixing sands and combating desertification.

Most species in Cistanche genus are traditionally used as nourishing and medicinal herbs, in particular, the species C. deserticola with the reputation of desert ginseng [5]. Several studies reported the chemical components and pharmacological effects of Cistanche species [6,7,8]. More than 100 compounds have been isolated from this genus, including phenylethanoid, glycosides, carbohydrates, lignans, iridoids, echinacoside, verbascoside, chlorogenic acid, acteoside, luteoloside, among others [9, 10]. These isolated compounds have exhibited interesting pharmacologic effects, such as neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, anti-senescence, anti-inflammatory, anti-osteoporosis, hepatoprotection, anti-oxidative, anti-bacterial, anti-tumor and glucose tolerance improving effects [10,11,12]. Driven by these medicinal properties and economic benefits, people overexploit and consume Cistanche species, giving to these species the importance highlighted in this work.

To date, four Cistanche species have been reported in China, namely C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. sinensis and C. tubulosa [13]. However, the classification of Cistanche remains controversial due to the following reasons: First, there are too few existing voucher specimens; second, the number of related literatures is scarce; third, the color of the flowers, in fresh and dried specimens, differ significantly becoming confusing the species classification based on flower color; fourth, the type of host plant is difficult to determine. Najibeh Ataeia et al. had reported molecular phylogeny analysis of a large-scale sampling of Cistanche species, indicating the presence of four clades based on their geographic distribution [14]. However, this study didn’t solve the problem of interspecies identification. In addition, the most economically important species, C. deserticola was not included. Therefore, we aimed to collect Cistanche species in China and determine their evolutionary status through phylogenetic analysis.

The chloroplast is an organelle peculiar to green plants, plays a crucial part in photosynthesis, and possess its own genome [15]. Chloroplast genomes are highly conserved, including genome size, structure, gene content, and organization [16, 17]. Consequently, the chloroplast genome is an excellent tool for phylogenetic analyses, genetic diversity evaluation, and molecular identification. In recent years, the complete chloroplast genome sequence has been successfully used as a plant super-barcode to distinguish closely related species in some taxa, such as Paeonia L. [18]. Whereas in other cases, chloroplast-derived DNA markers have been developed to authenticate medicinal plants as such, due to the lack of or reduced number of morphological based characters to differentiate among species, like the SNPs or insertion-deletion mutations (Indels) of the intergenic regions in the plastome of Panax ginseng species [19, 20].

During the process of our study, the plastic genome sequences of four Cistanche species were published. Severe gene loss and pseudogenization within Cistanche species plastomes were discussed, but only shown as supplementary material [1, 21]. In this work, for the first time, we used five full Cistanche species plastomes to: (1) explore structural variations within the Cistanche plastomes; (2) to illustrate the phenomena of gene loss and pseudogenization within Cistanche species; and (3) to develop taxa-specific molecular markers and DNA barcodes to distinguish between Cistanche species. The results here obtained have improved the understanding of relationships among Cistanche species, and will be invaluable for ensuring the effective and safe use of Cistanche species-based medicinal products.

Results

Sequencing and assembly of Cistanche plastomes

Illumina reads were mapped to the assembled plastomes, obtaining a mean coverage depth of 100–300 folds (Figure S1). The four plastomes displayed typical circular quadripartite structure, and showed a high degree of conservation in gene organization and structure (resumed in Figure S2). The quadripartite structure consisted in a Large Single-Copy (LSC) region (32,470–52,005 bp) and a Small Single-Copy (SSC) region (398–29,719 bp), separated by two Inverted Repeat (IR) regions (6,593–30,352 bp) (Table S1). The schematic presentation of the plastomes for C. deserticola (Figure S3), C. salsa (Figure S4), C. tubulosa (Figure S5) and C. sinensis (Figure S6) were shown. The sizes of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. sinensis and C. tubulosa plastomes were 109, 454 bp, 111,690 bp, 111,500 bp and 75,735 bp long respectively (Table S1). The overall GC contents of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. sinensis and C. tubulosa plastomes were 36.27%, 36.11%, 36.75% and 34.95%, respectively (Table S1). Generally, the GC content of SSC regions was lower than those of the LSC and IR regions, except for C. tubulosa. The gene contents of the five plastomes were listed in Table S1. The numbers of all genes, containing protein-coding genes (PCGs), putative pseudo genes, tRNA genes, and rRNA genes predicted as well as those possibly missing were counted (Table S1). Overall, 29–44 PCGs had been possibly lost. The numbers were similar to those for the PCGs identified in these plastomes, indicating the large scale of gene loss and gene erosion in Cistanche plastomes.

Expansion and contraction of the SSC regions in the Cistanche plastomes

The SSC regions of the Cistanche plastomes contracted significantly compared with the plastomes of other Orobanchaceae species, with the sizes ranging from only 27 bp to 61,091 bp long (Fig. 1 A, Table S2). In contrast, the IR regions expanded significantly, with the sizes ranging from 2, 318 bp to 45,796 bp, compared with the length of the IR regions of 15 other Orobanchaceae plastomes being larger than 25 kb (Table S1, Table S2). It is noticeable that the SSC regions in C. deserticola (398 bp) and C. salsa (435 bp) were extremely short, and only contained the rpl32 gene (Fig. 1B). The SSC regions of C. tubulosa was the longest and approximately 29,719 bp. Eight PCGs were located in the SSC regions of C. tubulosa, including ycf2, ycf15, rps7, rps12, rpl23, rpl32, ycf1 and rps15 (Table S4). These observations suggest that the SSC region of Cistanche being hotspots for gene loss, pseudogenization and rearrangement (Figure S10). The size variation in the SSC region mainly resulted from the gene loss and pseudogenization of ndh, rps and ycf gene (Table S3). Furthermore, the junctions of IR/LSC and IR/SSC were highly variable in the Cistanche plastomes due to the expansion/contraction of IRs (Fig. 2). The junction of the LSC/IRa (IRb) region of C. deserticola and C. salsa were highly conserved, with the rpl32 gene located at the SSC region (Table S4). But the distance of the rpl32 gene from the boundary varied (Fig. 2). Compared with C. tubulosa, the order of rpl32 and rps15 genes in C. salsa and C. deserticola was opposite. Another interesting observation was that the ycf1 genes were located in both the IRb and SSC regions in C. sinensis and C. phelypea (Fig. 2). As shown in Figure S7, the plastomes were less conserved among these Cistanche species. A large number of genes were missing, including rpoA, rpoB, rpoC, rpoC2, psaB, psaD, psaI, petA, petB, petD, cemA, etc. (Table 1 and Table S5). Moreover, compared with C. deserticola, some large inversions were identified in the plastomes of C. salsa, C. sinensis, C. phelypaea and C. tubulosa (Figure S8). While, five Cistanche species reveal varying degrees of genome loss when compared with the non-parasitic Orobanchaceae species R. glutinosa (Figure S9).

Analyses of expansion and contraction of inverted repeats of the five Cistanche species. The genes present at the top of track transcribe counterclockwise, whereas genes present below the track transcribe clockwise. Schematic representation of the boundary areas of LSC (light blue), IRa (yellow), SSC (green), and IRb (yellow) region for Cistanche species. The species names are shown to the left. The junction sites between LSC and IRb (JLB), IRb and SSC (JSB), SSC and IRa (JSA), IRa and LSC (JLA) are marked with the perpendicular dashed lines. The genes rpl22 (dark blue), rps19 (light red), ycf1 (blue), ycf2 (dark blue), rps15 (light orange), rpl32 (light green), rpl2 (green) are shown above the plastomes. The numbers above the gene features denote the distance between the gene borders, either the start or end of genes and the junction sites

Gene loss and pseudogenization in the Cistanche plastomes

The SSC contraction and IR expansion were accompanied by gene loss and pseudogenization. We constructed a hierarchical clustering tree based on the ratio of gene loss and pseudogenes for 34 Orobanchaceae species, using Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum as outgroups (Fig. 3). Orobanchaceae included nine genera, such as Orobanche, Cistanche, or Phacellanthus, among others. Gene loss was present in the plastomes of most Orobanchaceae species, except for Rehmannia, compared with Arabidopsis thaliana (Table S5). It was noteworthy that the plastomes of Orobanchaceae were characterized by a large percentage of gene losses, ranging from 41.25%—75%. The lost genes were mainly concentrated on the groups of photosynthesis and energy production genes, like ndh or atp genes. Among the Cistanche plastomes, C. phelypaea and C. tubulosa had the largest percentage of gene loss and C. deserticola and C. salsa had the smallest percentage of gene loss (Fig. 3A, Table 1 and Table S5).

Inferred gene loss and pseudogenization in 36 Orobanchaceae species. Branch lengths of the tree are proportional to the maximum numbers of the lost genes or the pseudogenes. Heatmap is the ratio of lost genes to pseudogenes. Hierarchical clustering tree was conducted using dendro. A) Hierarchical clustering tree based on ratio of gene loss. B) Hierarchical clustering tree based on ration of pseudogenes

All plastid genes of Pedicularis ishidoyana, Orobanche austrohispanica, O. densiflora, O. pancicii, O. rapum genistae, Lindenbergia philippensis, Rehmannia glutinosa, and R. solanifolia were functional. Pseudogenes were found most frequently in Lathraea squamaria and Aphyllon californicum, the percentages of which were 41.25% and 37.5%, respectively. Among the Cistanche plastomes, the proportion of pseudogenes ranged from 0.16 to 0.29, being ordered as C. tubulosa (0.16), C. sinensis (0.19), C. deserticola (0.23), C. phelypaea (0.28), C. salsa (0.29) (Fig. 3B and Table S6). Most photosynthesis and energy production genes were pseudogenes in Cistanche species, including ndh, psa, psb, rps, rpl gene (Table S6).

Nucleotide substitution rates of PCGs in Cistanche plastomes

The dN/dS ratio (ω = dN/dS) and aBSREL model analyses provide a comprehensive understanding of the evolution of genes by checking diversifying selection processes among related species. In general, the substitution rate for the Cistanche genus plastomes was low, indicating that plastid genes were highly conserved. However, we detected signals of positive selection in ycf2 gene (C. deserticola ω = 1.24; C. salsa ω = 1.22; C. tubulosa ω = 1.17; C. sinensis ω = 1.10 and C. phelypaea ω = 1.12), and chpP and rpl22 gene within C. phelypaea and C. salsa (Fig. 4, Table 2). Other PCGs had mainly synonymous substitutions, with rps4 gene showing highest synonymous substitution rate (ω = 0.11) (Fig. 4).

Phylogenetic analysis and estimation of divergence time of Cistanche species

We inferred the species phylogenetic tree using the Maximum likelihood (ML) method with the shared PCGs among 36 Orobanchaceae species (Table S2, Figure S11), and then the tree was calibrated with fossil record data of Arabidopsis thaliana-Nicotiana tabacum with BEAST (Figure S12). The Cistanche species here tested shown a monophyletic origin as previously determined, with a low branch supporting value (BS: 66), being distributed in three main clades with C. sinensis as basal species/clade (Figure S11). The second clade contained C. deserticola and C. salsa (BS:100) (Figure S11), both had similar plastome structure (Table S1). The third clade contained C. tubulosa and C. phelypaea (BS:100) (Figure S11), whose SSC region had similar length and composition (Table S1, Table S4). After this initial ML phylogenetic reconstruction, divergence time was established, with Pedicularis cheilanthifolia as root species of Orobanchaceae with divergence time estimated in 155 million years ago (Mya) (Figure S12). The monophyletic group of the Cistanche genus was diverged at about ~ 95.7 Mya, with C. sinensis splitting at ~ 77.3 Mya, and the remaining Cistanche species clades separating ~ 45.2Mya. The split between C. tubulosa and C. phelypaea occurred approximately ~ 22.9 Mya, whereas C. deserticola and C. salsa were relatively young; their split was estimated to be ~ 12.3 Mya (Figure S12).

Identification of highly variable intergenic regions in Cistanche species

To identify the most suitable regions to develop Cistanche species-specific molecular markers Kimura two-parameter distances were determined in homologous intergenic regions (with dismat script on EMBOSS package; Fig. 5A). The most divergent intergenic regions among the five plastomes were the clpP-rps11 (40.62), rpl33-rps18 (14.97), infA-rps8 (14.64), rpl36-infA (14.38), rpl16-rps3 (12.81) and rps18-rpl20 (10.18) (Fig. 5A).

Identification of hyper variable intergenic spacer regions within Cistanche species, and validation of the developed Cis-mk01 and Cis-mk02 DNA barcode markers. A) Comparison of the variability of IGS regions among the plastomes of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. tubulosa, C. sinensis and C. phelypaea. The X-axis indicates the IGS regions; the Y-axis shows the range of K2p distances between different pairs of species, with the average K2p distance identified with a diamond. B) Sequencing chromatograms of the Cis-mk01 marker regions from C. sinensis (Cisi), C. deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa), and C. tubulosa (Citu), with consensus sequence and alignment. C) Sequencing chromatograms of the Cis-mk02 marker regions from C. sinensis (Cisi), C. deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa), and C. tubulosa (Citu), with consensus sequence and alignment

Development and validation of molecular markers for Cistanche species discrimination

We selected one of the hypervariable intergenic spacer regions (IGS) identified previously, trnR-ACG-trnN-GUU, to develop two DNA barcode markers named Cis-mk01 and Cis-mk02, respectively, with designed primers listed on Table S7. Markers were tested by PCR amplification on total DNAs from all four Cistanche samples (Figure S13). Sequence analysis of each PCR product allowed identifying that marker Cis-mk01 had nine specific SNP loci and three Indel loci (Fig. 5B) whereas marker Cis-mk02 had fourteen specific SNP loci and three Indel loci (Fig. 5 C). These SNP and indels allowed to differentiate successfully all the four Cistanche species.

Specific DNA barcode maker design for Cistanche species

As explained in the introduction, highly variable regions in the plastome can be used for DNA barcode marker development. In this work, we used the EcoPrimer software to identify these hyper-variable regions as species-specific barcode and to design a pair of primers for each region for an accurate identification of each Cistanche species (Table S7). Eleven barcoding regions were verified (Fig. 6 and S14), of which Cis-mk03 showed 15 specific SNPs (Fig. 6A) and Cis-mk04 showed 14 specific SNPs (Fig. 6B) being able to differentiate successfully all the four Cistanche species used in this work. And the other nine of the eleven were shown in Figure S15.

Validation of Cis-mk03 and Cis-mk04 developed to differentiate among Cistanche species. A) Sequencing chromatograms of Cis-mk03 regions from C. sinensis (Cisi), C. deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa), and C. tubulosa (Citu), with consensus sequence and alignment. B) Sequencing chromatograms of Cis-mk04 regions from C. sinensis (Cisi), C. deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa), and C. tubulosa (Citu), with consensus sequence and alignment

Discussion

Large structural variations in Cistanche plastomes

Most plastomes of land plants are highly conserved in terms of genome structure, gene order and actual gene content, among other features [22, 23]. The plant plastomes are mainly between 115-165 kb long, have a typical quadripartite structure, and encode 105–135 genes, including 70–90 PCGs, eight rRNA genes and 30–40 tRNA genes, which are generally located on the LSC or SSC regions (about 15–20 genes are located in the IR region). In our study, we determined that the four Cistanche plastomes studied had a smaller size (less than 115 kb), and encoded less number of genes. These observations are consistent with the holoparasitic lifestyle of the Cistanche species. As they obtain the carbon, water, as well as other nutrients from their host’s roots or shoots, meaning that the photosynthetic ability in these plants is not needed, their plastomes are prone to gene reduction without affecting plants’ survivability [1, 24, 25]. Previous studies showed that the structural similarity of the five Cistanche species was relatively high [21]. However, our results shown that IR regions had shrunk and expanded to different degrees in the studied Cistanche species. Among them, the C. deserticola and the C. salsa had expanded dramatically (up to 30, 352 bp), while the C. tubulosa had contracted dramatically (down to 6, 593 bp). It is noteworthy that four rRNA genes (rrn16, rrn23, rrn4.5 and rrn5) were duplicated in the IRs in the Cistanche species studied except in C. tubulosa. In this species, these four rRNA genes are located as single copy, in the SSC region, explaining its relatively longer SSC and shorter IR (see Figure S5). Besides, as the most conservative region in plastomes, the sharp contraction of IRs indicated that C. tubulosa had gone through a much more intense gene loss, as reflected in its plastome size (C. tubulosa, 75, 375 bp), being the smallest of the five species under study. We speculated that this might be due to the tremendous difference in the growth environments of Cistanche species, leading to the significant different plastome structures among Cistanche species [26, 27].

Extensive gene loss and pseudogenization in Cistanche plastomes

Compared to more than 7372 completely sequenced plastome of land plants, the number of fully sequenced plastomes of non-photosynthetic plants is very small (approximately 100 at the date of ending this study). To date, only a few plastomes of holoparasitic plants have been reported, such as some species from Orobanchaceae [24, 28], Cuscutoideae [29], and Monotropa [30] among others. In this study, we have sequenced the plastomes of four Cistanche species, a holoparasitic species from Orobanchaceae. The phylogenomic comparison with other non-parasitc plants will provide further insights on parasitic plastomes evolution.

Within the four new Cistanche plastomes, all the genes related to photosynthesis and energy production were pseudogenized or lost, in agreement with the holoparasitic and heterotrophic lifestyle of Cistanche genus. All ndh genes are either absent or pseudogenized, with the ratio of missing genes higher than pseudogenes. Chloroplast ndh genes encode subunits of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-plastoquinone oxidoreductase complex, thought to reduce photo oxidative stress, which occurs when high light intensities exceed the capacity of the photosynthetic apparatus, resulting in the production of damaging reactive oxygen species [31]. Cuscuta reflexa, a holoparasitic plant within the Convovulaceae, appears to have an intact chloroplast genome, that also has lost all ndh genes [32], while genes atp, pet, psa and psb genes are either lost or pseudogenized. The ratio of pseudogenes is higher than those of lost genes in this species. Other parasitic species also have atp, pet, psa and psb genes as missing genes or as pseudogenes [33, 34]. Therefore, this phenomenon of gene loss and pseudogenization in Cistanche genus should be responsible for their simplified reduced plastome, common with other parasitic plant to adapt to their living style and environment.

Consolidation of two species: C. deserticola and C. salsa

There has been a debate whether or not C. deserticola and C. salsa should be considered two distinct species [27, 35]. Previous work shows that C. salsa exhibited similar chemical composition and pharmacological activities to those of C. deserticola, and has been used as a local medicinal herb in Ningxia and Gansu province of China [36,37,38]. Likely suggesting that both species are really only one. Our findings revealed that C. deserticola and C. salsa had very similar plastome structures, lengths and composition (C. deserticola 109, 454 bp with 36.27% GC content and C. salsa, 111,690 bp with 36.11% GC content, see Table S1). With similar lengths of the typical four subregions (LSC, IRs, SSC), including the extremely short SSC region that seems be disappearing. The ML phylogenetic tree shown that C. deserticola and C. salsa gather together as a separate group from other Cistanche species (Figure S11). Moreover, the mean divergence time of these two sister species was estimated at 12.3 Mya. Furthermore, through field survey, we found that C. salsa has the same growing environment as C. deserticola but much larger reserves in nature. As a result, we propose that the two species should be considered one species. C. salsa might be utilized as Cistanches herb in Chinese Pharmacopoeia to solve the urgent problem of resource shortage.

Conclusions

We presented a comparative analysis of five plastomes from Cistanche species, showing structure variation due to gene loss and pseudogenization, affecting mainly to photosynthetic genes. The genome sizes of these Cistanche species were smaller than that of other angiosperms. In particular, C. deserticola and C. salsa experienced significant SSC contraction and IR expansion, and C. tubulosa experienced SSC expansion and IR contraction. Phylogenetic relationships indicate that the Cistanche genus is a monophyletic group established around 95.7 Mya, with C. deserticola and C.salsa as two recognized species. Sequence variation among species allowed the development of two DNA barcode markers, Cis-mk01 and Cis-mk02, and eleven DNA barcode makers (Cis-mk03 to Cis-mk13) developed in a highly diverged intergenic region, that allow for the discrimination among Cistanche species from China. These results here obtained can improve our understanding on the classification system of Cistanche, plastome evolution, and the discrimination of medicinal products derived from Cistanche species.

Methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Fresh samples of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. sinensis, and C. tubulosa were collected from the Alxa League (Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region), Tacheng City (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region), Qingtongxia City (Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region), Hotan Prefecture (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region), China, respectively (Fig. 7). Samples were taken from the Cistanche planting base without harming wild species, complying with local and national ethical requirements. The samples were identified by Professor Yulin Lin and stored at the Herbarium of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medicinal College (under specimens' registry numbers CMPB13484, CMPB13485, CMPB13486 and CMPB13487). Fresh samples were covered within tin foil, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and kept in -80 °C until use. A plant genomic DNA extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) was used for total DNA extraction. Total DNA quality was assessed by gel electrophoresis in 1% (w/v) agarose, and quantified in Qubit 3.0 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Geographical distribution and growing environment of four Cistanche species. Red dot: Cistanche deserticola, also known as ‘Rou Cong rong’ in Alxa League, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Yellow dot: Cistanche salsa, also known as ‘Yan Sheng Rou Cong Rong’ in Tacheng City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Blue dot: Cistanche sinensis, also known as ‘Sha Cong Rong’ in Qingtongxia City, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China. Green dot: Cistanche tubulosa, also known as ‘Guan Hua Rou Cong Rong’ in Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China

Genome sequencing, assembly and validation

About 500 ng DNA was utilized to build a paired-end library with an insert size of 500 bp following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Consequently, a total of ~ 5G data for each species were obtained. All the plastomes of plants recorded in the GenBank were downloaded to build a local database. Clean paired-end reads were filtered against the local database by using BLASTn with a cutoff value of 1e-5. The filtered reads were used for downstream genome assembly with SPAdes (v. 3.10.1) [39]. To validate the correctness of the complete draft plastome, we mapped all raw reads to the draft plastome using Bowtie 2(v. 2.0.1) [40] and coverage graph was constructed by ggplot2 [41]. The dot plot of each plastome and themselves were constructed and visualized for evaluating the conserved quadripartite structure.

Genome annotation, lost genes and pseudogenes identification

CpGAVAS2 web service [42] were used to annotate each of the four plastomes. Cutoffs for the E-values of BLASTn and BLASTx were set to 1E-10 to assign each gene, being edited manually with Apollo genome editor [43]. The circular gene maps were drawn in https://www.cloudtutu.com/. GC contents for each gene and plastome was determined with CGView Server [44]. The assembled plastomes have been deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers: MN614127 (C. deserticola), MN614128 (C. salsa), MN614129 (C. sinensis) and MN614130 (C. tubulosa). The plastome data of Cistanche phelypaea (NC_025642.1) was downloaded from NCBI and included in our downstream analysis.

Genes that were similar to known PCGs but were truncated or contained one or more frame shift mutations compared to the nonparasitic plant of Orobanchaceae Rehmannia glutinosa (NC_034308) were defined as pseudogenes [24]. Genes that missed compared to the nonparasitic plant of Orobanchaceae R. glutinosa (NC_034308) were defined as lost genes. The ratio of lost genes and pseudogenes was calculated in flowing formula: Ratio of lost genes (pseudogenes) = number of lost genes (pseudogenes)/ number of PCGs in R. glutinosa. Then we built the topology tree using R package ‘PD’ based on the ratio of lost genes and pseudogenes.

Genome comparison

We conducted a comparative genome analysis for the Cistanche plastomes using software mVISTA [45] in the Shuffle-LAGAN mode. The annotated Rehmannia glutinosa [46] plastome was used as the reference in the analysis. Plastome genetic architecture of five Cistanche species in LSC/IRs and SSC/IRs borders were analyzed by IRscope [47]. Conserved sequences were identified between the five Cistanche plastomes by using BLASTN with an E-value cutoff of 1e-10. The homologous regions and gene annotations were visualized using a web-based genome synteny viewer GSV [48]. Gene rearrangements of the five Cistanche plastomes were analyzed using Mauve [49].

Identification of hypervariable regions

To identify the most divergent regions, we wrote a custom script to extract the start and end of the IGS regions from the GenBank files for the five plastomes. A total of 25 IGSs shared by the five Cistanche plastomes were identified. The sequences were extracted and aligned using the ClustalW2 (v.2.0.12) program with options “-type = DNA –gapopen = 10 –gapext = 2” [50]. Pairwise distances were calculated using the K2p evolution model implemented in the distmat program from the EMBOSS package [51].

Selective pressure analysis

Adaptive branch-site random effects likelihood (aBSREL) model [52] implemented in Hyphy [53] was used to determine the selective pressure analysis. We used the RevTrans v2.0 [54] to align the DNA sequences of 18 PCGs guided by their protein sequences with the option of CLUSTALW2. The significance analysis was performed using the likelihood ratio test (p ≤ 0.05) after correcting for multiple testing implemented in the program. We used the yn00programme in PAML v 4.9 [55] to calculate the nonsynonymous substitution rate (dN) and synonymous substitution rate(dS) for 18 PCGs with the F3X4 codon model. The ML tree inferred from shared PCGs was used as the input tree.

Phylogenetic analyses

For phylogenetic analyses, the DNA sequences of shared plastome PCGs from 36 Orobanchaceae species including the Cistanche species of this work (Table S1) were aligned using ClustalW program [56]. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed with the software Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) [57], using Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum as outgroups. The detailed parameters were “raxmlHPC-PTHREADS-SSE3 -fa -N 1000 –m PROTGAMMACPREV/GTRGAMMA—× 551,314,260 -p 551,314,260 -o Arabidopsis_thaliana, Nicotiana_tabacum -T 20”. Bootstrap testing with 1,000 replications was used to assess the significant level of the phylogenetic tree, and the bootstrap values of each branch were displayed beyond each node.

Molecular clock analyses

We used the software BEAST [58] for molecular clock analysis on the shared plastome PCGs alignment, using fossil information of A. thaliana and N. tabacum, and the cpREW amino acid substitution model for chloroplast DNA [59]. Phylogenetic inference following MCMC analysis with default settings was performed (20,000,000 generations, Yule speciation tree prior to the substitution rate, the trees sampled every 1,000 generations) under a strict clock approach. TRACER software was used to check the acceptability and convergence to the stationary distribution of trees [60], while TREEANNOTATOR software was used to generate the maximum clade credibility tree from the obtained trees after setting a burning-in of 10% [61]. The tree was visualized with FigTree (v. 1.4.3; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/, October 2019).

DNA barcode marker identification using EcoPrimer

EcoPrimer software was used to identify the DNA barcode maker based on the complete plastome sequences [62]. To achieve it, we download the C. phelypaea plastome and combined it with the four Cistanche plastomes sequences obtained in this study. The command "ecoPCRFormat.py-g-n Cistanche.Fo-t Taxonomy Cistanche.gb" was used to build the database. Subsequently, the command "ecoPrimer-d Cistanche.Fo-l 100-L 1000-e 0-t species > Cistanche.Po" was run on the constructed database to find specific primers for each of the DNA barcode markers.

Identification and validation of molecular markers and ecoprimer for species discrimination

We used markers identified from the variable intergenic regions and ecoprimer to discriminate the four Cistanche species. Primers to discriminate between the four Cistanche species under study were designed on the variable intergenic regions using Snapgene 6.0 (Snapgene from Insightful Science, available at http://www.snapgene.com, last used on 2022), or were those selected with EcoPrimer software on the barcoding regions (Table S7 and S8). PCR amplifications were performed in a final volume of 20 μL with 10 μL 2 × Taq PCR Master Mix, 0. 5 μM of each primer, 5 μL template DNA, and 4 μL ddH2O following the manufacturer’s instructions (Mei5 Biotechnology, Co., Ltd). All amplifications were carried out in a Pro-Flex PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) under the following conditions: denaturation at 95 ℃ for 3 min, followed by 36 cycles of 94 ℃ for 25 s and 55℃ for 10 s, and 72 ℃ for 2 min as the final extension following the manufacturer’s instructions (Mei5 Biotechnology, Co., Ltd). PCR amplicons were visualized on 1% agarose gels, purified and then subjected to bidirectional Sanger sequencing on an ABI 3730 XL instrument (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the same set of primers used for PCR amplification with BigDye v3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Availability of data and materials

The assembled plastid genomes of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. tubulosa and C. sinensis were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers MN614127, MN614128, MN614130 and MN614129.

Abbreviations

- CDS:

-

Protein coding sequences

- GC:

-

Guanine-cytosine

- IGS:

-

Intergenic sequences

- IR:

-

Inverted repeat

- IRa:

-

Inverted repeat A

- IRb:

-

Inverted repeat B

- IRs:

-

Inverted repeat regions

- kb:

-

Kilobase

- LSC:

-

Large single copy

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- rRNAs:

-

Ribosomal RNAs

- SC:

-

Single copy

- SSC:

-

Small single copy

- tRNAs:

-

Transfer RNAs

- GS:

-

Genome size

- PCGs:

-

Protein-coding genes

References

Li X, Zhang TC, Qin Q, Ren Z, Zhao J, Takahiro Y, Masami H, Crabbe M, Li J, Yang Z. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of holoparasite Cistanche deserticola (Orobanchaceae) reveals gene loss and horizontal gene transfer from its host Haloxylon ammodendron (Chenopodiaceae). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58747.

Westwood JH, Yoder JI, Timko MP, dePamphilis CW. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(4):227–35.

Wickett NJ, Honaas LA, Wafula EK, Das M, Huang K, Wu BA, Landherr L, Timko MP, Yoder J, Westwood JH, et al. Transcriptomes of the Parasitic Plant Family Orobanchaceae Reveal Surprising Conservation of Chlorophyll Synthesis. Curr Biol. 2011;21(24):2098–104.

Thorogood CJ, Leon CJ, Lei D, Aldughayman M, Huang Lf, Hawkins JA. Desert hyacinths: an obscure solution to a global problem? Plants, People, Planet. 2021;3(4):302–7.

Wang T, Zhang X, Xie W. Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma, “Desert Ginseng”: A Review. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40(6):1123–41.

Bougandoura A, D’Abrosca B, Ameddah S, Scognamiglio M, Mekkiou R. Chemical constituents and in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Cistanche violacea Desf. (Orobanchaceae) extract. Fitoterapia. 2016;109:248–53.

Tian S, Miao M, Bai M, Wei Z. Phenylethanoid Glycosides of Cistanche on menopausal syndrome model in mice. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(4):537–47.

Wang D, Wang H, Li G. The antidepressant and cognitive improvement activities of the traditional Chinese herb Cistanche. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:1–9.

Zan K, Jiao XP, Guo LN, Zheng J, Shuang-Cheng MA. HPLC specific chromatogram of Lamiophlomis Herba and its counterfeit and determination of four effective components. China J Chin Materia Med. 2016;41(12):2284–90.

Fu Z, Fan X, Wang X, Gao X. Cistanches Herba: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics property. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;219:233–47.

Wang N, Ji S, Zhang H, Mei S, Qiao L, Jin X. Herba Cistanches: Anti-aging. Aging Dis. 2017;8(6):740–59.

Morikawa T, Xie H, Pan Y, Ninomiya K, Muraoka O. A Review of Biologically Active Natural Products from a Desert Plant Cistanche tubulosa. Chem Pharm Bull. 2019;67(7):675–89.

Zhang Z, Tzvelev NN. Orobanchaceae. Flora of China. Beijing: Science press; 1998:18;229–43.

Ataei N, Schneeweiss GM, Garcia MA, Krug M, Lehnert M, Valizadeh J, Quandt D. A multilocus phylogeny of the non-photosynthetic parasitic plant Cistanche (Orobanchaceae) refutes current taxonomy and identifies four major morphologically distinct clades. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2020;151:106898.

Brunkard JO, Runkel AM, Zambryski PC. Chloroplasts extend stromules independently and in response to internal redox signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(32):10044–9.

Tonti-Filippini J, Nevill PG, Dixon K, Small I. What can we do with 1000 plastid genomes? Plant J. 2017;90(4):808–18.

Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76:273–97.

Guo LL, Guo S, Xu J, He LX, Carlson JE, Hou XG. Phylogenetic analysis based on chloroplast genome uncover evolutionary relationship of all the nine species and six cultivars of tree peony. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;153:112567.

Binh NV, Ngoc L, Espinosa WN, Hyun-Seung P, Nam-Hoon K, Woojong J, Junki L, Yang TJ. Comprehensive comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes from seven Panax species and development of an authentication system based on species-unique single nucleotide polymorphism markers. J Ginseng Res. 2020;44:135–44.

Kyunghee K, Sang-Choon L, Junki L, Oh LH, Jun JH, Nam-Hoon K, Hyun-Seung P, Yang TJ, Berthold H. Comprehensive survey of genetic diversity in chloroplast genomes and 45S nrDNAs within Panax ginseng species. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0117159.

Liu XQ, Fu WR, Tang YW, Zhang WJ, Song ZP, Li LF, Yang J, Ma H, Yang JH, Zhou C, et al. Diverse trajectories of plastome degradation in holoparasitic Cistanche and genomic location of the lost plastid genes. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(3):877–92.

Kato T, Kaneko T, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S. Complete structure of the chloroplast genome of a legume. Lotus japonicus DNA Res. 2000;7(6):323–30.

De Las Rivas J. Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes: functional annotation, genome-based phylogeny, and deduced evolutionary patterns. Genome Res. 2002;12(4):567–83.

Cusimano N, Wicke S. Massive intracellular gene transfer during plastid genome reduction in nongreen Orobanchaceae. New Phytol. 2016;210(2):680–93.

Park I, Song JH, Yang S, Kim WJ, Choi G, Moon BC. Cuscuta species identification based on the morphology of reproductive organs and complete chloroplast genome sequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2726.

Sun X, Li L, Pei J, Liu C, Huang L. Metabolome and transcriptome profiling reveals quality variation and underlying regulation of three ecotypes for Cistanche deserticola. Plant Mol Biol. 2020;102(3):253–69.

Wang Y, Zhang L, Du Z, Pei J, Huang L. Chemical diversity and prediction of potential cultivation areas of Cistanche herbs. Sci Rep. 2019;9:19737–50.

Wicke S, Kai FM, Pamphilis C, Quandt D, Wickett NJ, Yan Z, Schneeweiss R. Mechanisms of functional and physical genome reduction in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic parasitic plants of the broomrape family. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3711–25.

Funk HT, Berg S, Krupinska K, Maier UG, Krause K. Complete DNA sequences of the plastid genomes of two parasitic flowering plant species, Cuscuta reflexa and Cuscuta gronovii. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:45.

Gruzdev EV, Mardanov AV, Beletsky AV, Kochieva EZ, Ravin NV, Skryabin KG. The complete chloroplast genome of parasitic flowering plant Monotropa hypopitys: extensive gene losses and size reduction. Mitochondrial DNA Part B-Resources. 2016;1(1):212–3.

Quiles MJ. Stimulation of chlororespiration by heat and high light intensity in oat plants. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010;29(8):1463–70.

Haberhausen G, Zetsche K. Functional loss of all ndh genes in an otherwise relatively unaltered plastid genome of the holoparasitic flowering plant Cuscuta reflexa. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24(1):217–22.

Wickett NJ, Zhang Y, Hansen SK, Roper JM, et al. Functional gene losses occur with minimal size reduction in the plastid genome of the parasitic liverwort Aneura mirabilis. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(2):393–401.

Ravin N, Gruzdev E, Beletsky A, Mazur A, Prokhortchouk E, Filyushin M, Kochieva E, Kadnikov V, Mardanov A, Skryabin K. The loss of photosynthetic pathways in the plastid and nuclear genomes of the non-photosynthetic mycoheterotrophic eudicot Monotropa hypopitys. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:328.

Sun X, Pei J, Zhao L, Ahmad B, Huang LF. Fighting climate change: soil bacteria communities and topography play a role in plant colonization of desert areas. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23(11):6876–94.

Jin XL, Zhang QR. Recent progress in the study on chemical constituents of herba Cistanche. China J Chin Materia Med. 1994;19(11):695.

Jiang Y, Tu PF. Analysis of chemical constituents in Cistanche species. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216(11):1970–9.

Hai-Ning LV, Zeng KW, Song YL, Jiang Y, Tu PF. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview of Cistanche Species. Recent Adv Polyphenol Res. 2016;5:313–41.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Wickham H. Getting started with ggplot2. ggplot2. New York: Springer; 2016:11–31.

Shi LC, Chen HM, Jiang M, Wang LQ, Wu X, Huang LF, Liu C. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W65–73.

Lewis SE, Searle SMJ, Harris N, Gibson M, Lyer V, Richter J, Wiel C, Bayraktaroglu L, Birney E, Crosby MA, et al. Apollo: a sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol. 2002;3(12):0082.0081-0082.0014.

Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W181–4.

Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–9.

Zeng SY, Zhou T, Han K, Yang YC, Zhao JH, Liu ZL. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of six Rehmannia species. Genes. 2017;8(3):103.

Amiryousefi A, Hyvonen J, Poczai P. IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):3030–1.

Revanna KV, Chiu CC, Bierschank E, Dong Q. GSV: a web-based genome synteny viewer for customized data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:316.

Darling A, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna A. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14(7):1394–403.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using clustalW and clustalX. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. vol. unit 2.3. USA: Wiley; 2003:2.3.1-2.3.22.

Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–7.

Smith MD, Wertheim JO, Weaver S, Murrell B, Scheffler K, Pond SLK. Less is more: an adaptive branch-site random effects model for efficient detection of episodic diversifying selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(5):1342–53.

Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(5):676–9.

Wernersson R, Pedersen AG. RevTrans: multiple alignment of coding DNA from aligned amino acid sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3537–9.

Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–91.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL-W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–80.

Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3.

Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kuhnert D, Vaughan T, Wu CH, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. BEAST 2: a software platform for bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(4):e1003537.

Adachi J, Waddell PJ, Martin W, Hasegawa M. Plastid genome phylogeny and a model of amino acid substitution for proteins encoded by chloroplast DNA. J Mol Evol. 2000;50(4):348–58.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA. Posterior summarization in bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biol. 2018;67(5):901–4.

Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchene S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kuhnert D, De Maio N, et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Computational Biol. 2019;15(4):e1006650.

Riaz T, Shehzad W, Viari A, Pompanon F, Taberlet P, Coissac E. ecoPrimers: inference of new DNA barcode markers from whole genome sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(21):e145.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank Beijing AVA Technology for their assistance in plastome sequencing.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.82073960), the Open Research Fund of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Key Laboratory of Systematic Research of Distinctive Chinese Medicine Resources in Southwest China (2021GZ2011003), National Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program of China (2018FY100701) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2021-12 M-1–022, 2021-I2M-1–071), which are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linfang Huang and Chang Liu conceived and designed the experiments. Yujing Miao, Haimei Chen, Wanqi Xu, Qiaoqiao Yang performed the data analysis; Qiaoqiao Yang performed DNA-extraction measurement and analysis. Yujing Miao performed molecular marker verified measurement. Yujing Miao wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This research abided by the ‘Regulations of the people’s Republic of China on the protection of wild plants’ on ethical standards and did not involve collection of wild resources.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

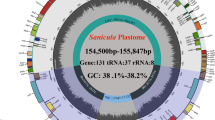

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Characteristics of the five Cistanche species plastomes. Table S2. Details of plastome or chloroplast genome sequences downloaded from NCBI used in this study. Table S3. Gene content in SSC region of Orobanchaceae species. Table S4. The position of genesin LSC, IR and SSC regions in five Cistanche species. Table S5. The list of lost genes in Orobanchaceae species. Table S6. The list of pseudogenes in Orobanchaceae species. Table S7. The thirteen pairs of primers for the ampilification of DNA barcode markers. Fig. S1. The coverage depth of the four Cistanche plastomes. The raw sequence reads were mapped to the reference plastome sequences. A) C. deserticola; B) C. salsa; C) C. sinensis; D) C. tubulosa. The X-axis shows the plastome positions. The Y-axis shows the depth. The Y-axis shows the coverage depth of the mapped reads. Fig. S2. The dot plots showing the self-2-selfalignment of the four Cistanche plastomes sequences. The plots were generated using Gepard. A) C. deserticola; B) C. salsa; C) C. sinensis; D) C. tubulosa. Fig. S3. A schematic map of the Cistanche deserticola plastome.The first circle shows the species name and specific information regarding the genome (length, GC content, and the number of genes) from the center going outward. The second circle shows the length of the corresponding single short copy (SSC), inverted repeat (IRa and IRb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions from the center going outward. The third circle shows the GC content. The outer circle shows the gene names and their optional codon usage bias in parentheses.The genes are colored based on their functional categories. Genes inside andoutside of the circle are transcribed in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, represented with arrows. Fig. S4. A schematic map of the Cistanche salsa plastome. The first circle shows the species name and specific information regarding the genome (length, GC content, and the number of genes)from the center going outward. The second circle shows the length of the corresponding single short copy (SSC), inverted repeat (IRa and IRb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions from the center going outward. The third circle shows the GC content. The outer circle shows the gene names and their optional codon usage bias in parentheses. The genes are colored based on their functional categories. Genes inside and outside of the circle are transcribed in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, represented with arrows. Fig. S5. Aschematic map of the Cistanche tubulosa plastome. The first circle showsthe species name and specific information regarding the genome (length, GCcontent, and the number of genes) from the center going outward. The second circle shows the length of the corresponding single short copy (SSC), invertedrepeat (IRa and IRb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions from the center going outward. The third circle shows the GC content. The outer circle shows the gene names and their optional codon usage bias in parentheses. The genes are coloredbased on their functional categories. Genes inside and outside of the circle are transcribed in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, represented with arrows. Fig. S6. A schematic map of the Cistanche sinensis plastome.The first circle shows the species name and specific information regarding thegenome (length, GC content, and the number of genes) from the center going outward. The second circle shows the length of the corresponding single shortcopy (SSC), inverted repeat (IRa and IRb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions from the center going outward. The third circle shows the GC content. The outer circle shows the gene names and their optional codon usage bias in parentheses.The genes are colored based on their functional categories. Genes inside andoutside of the circle are transcribed in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, represented with arrows. Fig. S7. Identity plot comparingthe plastid genomes of C. deserticola, C. salsa, C. sinensis,C. tubulosa and C. phelypaea using Rehmannia glutinosa as a reference sequence. The vertical scale indicates the percentage of identity(50% to 100%), using a 50% identity cutoff. The horizontal axis indicates the coordinates in the plastomes. Genome regions are color-coded as protein-coding, rRNA, tRNA, intron, and conserved non-coding sequences (CNS). Fig. S8. Synteny analyses of plastomes for five Cistanche species. Each horizontal black line represents a genome, with conserved regions connected with colored blocks. The plastome sequence of C. deserticola was used as the reference. Fig.S9. Synteny analyses of five Cistanche plastomes compared with Rehmannia glutinosa. Each horizontal black line represents a genome, with conserved regions connected with colored block. The plastome of R. glutinosa was used as the reference. Fig. S10. Extent of the gene rearrangements of 5 Cistanche plastomes. Locally collinear blocks of the sequences are colour-coded and connected by lines. Fig. S11. Maximum likelihood (ML) Phylogenetic tree of 36 Orobanchaceae species. The Cistanche species are highlighted in blue. The bootstrap scores are shown on the corresponding branches. The detail information can be found in Table S2. Fig. S12. Maximum cladecredibility tree obtained from a molecules clock analysis using the BEAST software. The circles having different colors represent the genes positively selected in Orobanchaceae. The background of Cistanche is highlighted in light blue. The detail information can be found in Table S2. Fig.S13. The gel electrophoresis results of the PCR products amplified usingthe primers pairs list in Table S7 using DNA marker. Lane M was the marker of DL 2000. The lanes from left to right corresponded to products amplificated from the first individual of C. deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa),C. tubulosa(Citu), and C. sinensis (Cisi) by primer Cis-pp01 andCis-pp02, respectively. Fig. S14. The gel electrophoresis results of the PCR products amplified using the primers pairs list in Table S7 using DNAmarker. Lane M was the marker of DL 2000. The lanes from left to right corresponded to products amplificated from the first individual of C.deserticola (Cide), C. salsa (Cisa), C. tubulosa (Citu), andC. sinensis (Cisi) by primer Cis-pp03 to Cis-pp013, respectively. Fig.S15. The alignment of the sequencing chromatogram of the PCR products amplified using DNA marker (Cis-mk03 to Cis-mk13). SNP and Indel regions were highlighted with red squares. Cide: C. deserticola; Cisa: C. salsa;Citu: C. tubulosa; Cisi: C.sinensis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Miao, Y., Chen, H., Xu, W. et al. Structural mutations of small single copy (SSC) region in the plastid genomes of five Cistanche species and inter-species identification. BMC Plant Biol 22, 412 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03682-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03682-x