Abstract

Background

Microorganisms that activate plant immune responses are useful for application as biocontrol agents in agriculture to minimize crop losses. The present study was conducted to identify and characterize plant immunity–activating microorganisms in Brassicaceae plants.

Results

A total of 25 bacterial strains were isolated from the interior of a Brassicaceae plant, Raphanus sativus var. hortensis. Ten different genera of bacteria were identified: Pseudomonas, Leclercia, Enterobacter, Xanthomonas, Rhizobium, Agrobacterium, Pantoea, Rhodococcus, Microbacterium, and Plantibacter. The isolated strains were analyzed using a method to detect plant immunity–activating microorganisms that involves incubation of the microorganism with tobacco BY-2 cells, followed by treatment with cryptogein, a proteinaceous elicitor of tobacco immune responses. In this method, cryptogein-induced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in BY-2 cells serves as a marker of immune activation. Among the 25 strains examined, 6 strains markedly enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells. These 6 strains colonized the interior of Arabidopsis plants, and Pseudomonas sp. RS3R-1 and Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6 selectively enhanced plant resistance to the bacterial pathogens Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082, respectively. In addition, Pseudomonas sp. RS1P-1 effectively enhanced resistance to both pathogens. We also comprehensively investigated the localization (i.e., cellular or extracellular) of the plant immunity–activating components produced by the bacteria derived from R. sativus var. hortensis and the components produced by previously isolated bacteria derived from another Brassicaceae plant species, Brassica rapa var. perviridis. Most gram-negative strains enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells via the presence of cells themselves rather than via extracellular components, whereas many gram-positive strains enhanced ROS production via extracellular components. Comparative genomic analyses supported the hypothesis that the structure of lipopolysaccharides in the outer cell envelope plays an important role in the ROS-enhancing activity of gram-negative Pseudomonas strains.

Conclusions

The assay method described here based on elicitor-induced ROS production in cultured plant cells enabled the discovery of novel plant immunity–activating bacteria from R. sativus var. hortensis. The results in this study also suggest that components involved in the ROS-enhancing activity of the bacteria may differ depending largely on genus and species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological control of plant diseases using beneficial microorganisms has received considerable attention as a promising alternative to the use of pesticides, which exert potential adverse effects on both human health and soil microbial communities [1, 2]. A variety of pathogens attack plants in the environment, and in agriculture, this can lead to significant crop losses. Beneficial microorganisms protect plants from pathogens via several different mechanisms, including the production of antimicrobial compounds, competition with pathogens for space and nutrients, and activation of plant immune responses [3, 4]. Microorganisms that activate plant immune responses are useful for application as biocontrol agents in agriculture, as they function like vaccines in plants without causing unwanted adverse effects [5, 6]. Pathogen recognition by plants leads to the initiation of defense responses, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the expression of various defense-related genes, and the biosynthesis of phytoalexins and defense hormones [7,8,9]. Several types of plant-associated microorganisms can activate the plant immune system through a phenomenon known as induced systemic resistance (ISR) [10], which enables plants to engage more-rapid and stronger defense responses with no or low growth inhibition.

ISR mediated by plant-associated bacteria belonging to the genera Pseudomonas and Bacillus has been well studied to date [11,12,13,14]. For example, ISR in several plant species such as Arabidopsis and carnation can be provoked by the rhizobacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS417r [15, 16]. The rhizobacterium Bacillus cereus AR156 confers resistance in Arabidopsis to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato and the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea [17, 18]. In addition, endophytes are suitable for use as biocontrol agents because of their inherent ability to stably colonize the interior of plants [3, 4, 19, 20]. For example, the endophytic bacterium Streptomyces sp. EN27 can induce resistance in Arabidopsis to the bacterial pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum and the fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum via ISR [21, 22]. Pretreatment of Arabidopsis with the well-characterized endophytic bacterium Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN increases resistance to P. syringae pv. tomato [23, 24]. Recent reports indicate that Azospirillum sp. B510, an endophytic bacterium isolated from rice, induces disease resistance in rice and tomato [25, 26]. Identifying the different types of plant immunity–activating bacteria that inhabit plants would not only enhance understanding of plant-microbe interactions in nature but could also facilitate the application of these microorganisms as biocontrol agents.

Conventional methods to screen for plant immunity–activating bacteria are based on monitoring disease symptoms using whole plants and pathogens. However, these methods are cumbersome and tend to be laborious and time consuming. We have established a method using cultured plant cells to directly detect microorganisms that activate the plant immune system based on plant-microbe interactions [27]. In this method, tobacco BY-2 cells are incubated with a microorganism and then treated with cryptogein, a proteinaceous elicitor of tobacco immune responses secreted by the pathogenic oomycete Phytophthora cryptogea [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Cryptogein-induced production of ROS in BY-2 cells serves as a marker to assess the potential of a microorganism to activate the plant’s defense response. This method increases throughput in screening for microorganisms that “prime” and potentiate plant immune responses, and its use led to the discovery of novel plant immunity–activating bacterial endophytes from a Brassicaceae plant, Brassica rapa var. perviridis [27].

In the present study, we isolated endophytes from another Brassicaceae plant species, Raphanus sativus var. hortensis. We were interested in whether plant immunity–activating bacteria could be obtained from other plants of the same family, and whether there were differences in the types of plant immunity–activating bacteria. A total of 25 bacterial strains isolated from the plant interior were assayed using the described detection method, and strains that enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells were selected. After selection of the plant immunity–activating bacteria, 3 endophytes that induce bacterial pathogen resistance in whole Arabidopsis plants were identified. We also report here the characterization of the components involved in plant immune activation produced by bacteria obtained from the 2 Brassicaceae plant species.

Results

Isolation of bacteria from the interior of R. sativus var. hortensis plants

Microorganisms were isolated from the interior of R. sativus var. hortensis plants. Petioles and roots of the plants (Fig. S1) were surface-sterilized and placed on NBRC802 and ISP2 agar plates, as described in the Materials and Methods [27]. A total of 25 bacterial strains were isolated, of which 11 and 14 strains were derived from petioles and roots, respectively (Table S1). Taxonomic identification based on 16 S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that these bacteria belonged to 10 different genera: Pseudomonas, Leclercia, Enterobacter, Xanthomonas, Rhizobium, Agrobacterium, Pantoea, Rhodococcus, Microbacterium, and Plantibacter (Table S1 and Fig. 1). These strains were further divided into 2 phyla, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria (Fig. 1). Interestingly, 21 strains were classified as Proteobacteria, and 11 of these Proteobacteria strains belonged to the genus Pseudomonas (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic relationships of bacterial strains recovered from the interior of R. sativus var. hortensis plants based on 16 S rRNA gene sequences. Bootstrap values from 1000 replications are shown at each of the branch points on the tree. Strains RS1R-3 and RS1R-4 were not included in the phylogenetic tree because the region of the 16 S rRNA gene sequence read in these strains differed from that of the other strains, as described in the Materials and Methods

Assay of bacterial ability to prime plant immune responses

The relationship between the immune responses of tobacco BY-2 cells and the pathogenic oomycete–derived elicitor cryptogein has been well characterized [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Cryptogein triggers various immune responses in BY-2 cells, including ROS production. Using BY-2 cells and cryptogein, we previously established a method to directly detect microorganisms that activate the plant immune system (Fig. S2) [27]. This method involves incubation of a microorganism with BY-2 cells, followed by treatment with cryptogein and quantitative analysis of ROS production via chemiluminescence. In this process, before the addition of cryptogein, microorganism-treated BY-2 cells are collected and suspended in fresh buffer to remove metabolites derived from both microbial cells and BY-2 cells (e.g., organic compounds, ROS, and ROS scavengers). If a microorganism is capable of priming the immune response of BY-2 cells, pretreatment of the cells with that microorganism will enhance cryptogein-induced ROS production.

In this study, bacterial endophytes isolated from R. sativus var. hortensis plants were subjected to the assay to identify those capable of priming the plant immune response. Most of the isolated bacteria (19 strains) exhibited no or only minor effects on BY-2 cells during co-incubation (Fig. S3), but 6 strains markedly enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production by the BY-2 cells (Fig. 2): Pseudomonas sp. RS1P-1, Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6, Microbacterium sp. RS2P-3, Xanthomonas sp. RS2P-4, Enterobacter sp. RS2R-3, and Pseudomonas sp. RS3R-1. It is interesting to note that these plant immunity–activating bacteria belonged to distinct phylogenetic clusters (Fig. 1).

Cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells co-incubated with bacteria. Bacteria that enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production are shown. BY-2 cells were co-incubated with bacteria of each strain (∆) or subjected to mock treatment (only a mixture of medium and buffer, ○), and then cryptogein was added. ROS production was monitored based on chemiluminescence. The maximum value of the mock control was expressed as 1.0, and relative chemiluminescence intensity (RCI) is shown. Average values ± SE from three independent experiments are presented. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the mock control based on Student’s t-test (*, P < 0.05)

Biocontrol activity of selected bacteria

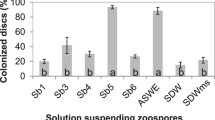

The selected bacteria were subjected to the assay using whole Arabidopsis plants. Each selected strain was inoculated into plants by immersing the root tip of seedlings into bacterial cell culture solution. We observed that 5 strains (RS1P-1, RS1R-6, RS2P-3, RS2P-4, and RS3R-1) had no effect on plant growth after inoculation, whereas the remaining strain (RS2R-3) significantly reduced plant growth after inoculation (Fig. S4). These strains colonized the interior of the Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 3). The number of bacteria ranged from 106 to 108 colony forming unit (CFU) per gram of Arabidopsis plant tissue, depending on the bacterial strain.

Colonization of Arabidopsis plants by selected bacteria. Plants were inoculated with each strain of selected bacteria by immersing the root tip of 7-day-old seedlings in bacterial cell culture solution, followed by cultivation for 7 days. After extracts of surface-sterilized plants were plated on medium, the number of colonies that formed on the plate was determined. No colonies were formed for plants that received mock treatment (only medium) instead of bacterial cell culture solution. Average values ± SE from three independent experiments are presented

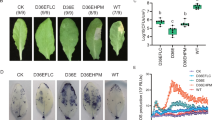

Arabidopsis seedling treated with each strain of the 5 endophytes was challenged with the hemibiotrophic bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mock-treated plants exhibited symptoms of severe chlorosis (Fig. 4a). In contrast, pretreatment with strains RS1P-1 and RS3R-1 resulted in significantly milder disease symptoms in plants compared to mock-treated plants (Fig. 4a). The density of strain DC3000 in Arabidopsis plants decreased to 4% and 15% following treatment with strains RS1P-1 and RS3R-1, respectively, compared with mock-treated plants (Fig. 4b). Similarly, although plants challenged with the necrotrophic bacterial pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082 exhibited soft rot, pretreatment with strains RS1P-1 and RS1R-6 significantly reduced plant disease symptoms (Fig. 4a and c). Notably, Pseudomonas sp. RS3R-1 and Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6 selectively enhanced plant resistance to P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082, respectively. Furthermore, Pseudomonas sp. RS1P-1 effectively enhanced resistance to both pathogens.

Pathogen resistance of Arabidopsis plants pretreated with selected bacteria. RS1P-1–, RS1R-6–, RS2P-3–, RS2P-4–, RS3R-1–, or mock (only medium)–treated Arabidopsis seedlings were cultivated for 7 days, and the plants were then challenged with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 or P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082 and cultivated for an additional 4 days. (a), representative photographs. (b), proliferation of strain DC3000. After plating extracts of surface-sterilized aerial tissues of plants on medium, the number of colonies of strain DC3000 that formed on the plate was determined. (c), severity of disease caused by strain NBRC 14082. Disease severity is indicated as a percentage calculated by dividing the number of damaged leaves by the number of all leaves. Average values ± SE from three independent experiments are presented. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the mock control based on Student’s t-test (*, P < 0.05)

Characterization of components that promote ROS production

We comprehensively characterized the components involved in plant immune activation produced by 14 strains derived from the 2 types of Brassicaceae plants. (Table 1). We used the ROS-enhancing strains isolated from B. rapa var. perviridis in our previous study [27] in addition to the ROS-enhancing strains isolated from R. sativus var. hortensis in this study to obtain more information on the plant immunity–activating components. We first evaluated the thermal stability of the components. Bacterial cell culture medium was autoclaved, and cryptogein-induced ROS were measured. As expected, the ROS-enhancing activity of most of the strains (11 strains) was lost after autoclaving (Table 1 and Fig. S5). However, surprisingly, the activity of Delftia sp. BR1R-2, Bacillus sp. BR2S-4, and Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6 was retained after autoclaving (Table 1 and Fig. S5). These results indicate that the components responsible for the ROS-enhancing activity of these 3 strains are highly thermostable.

We also investigated the localization of the components. Bacterial cell culture medium was centrifuged to separate the cells and extracellular components, and cryptogein-induced ROS production was assayed. Interestingly, the cellular fraction of 7 of the 8 gram-negative strains (1 Enterobacter strain, 4 Pseudomonas strains, 1 Xanthomonas strain, and 1 Delftia strain) exhibited ROS-enhancing activity, but the extracellular component fraction did not (Table 1 and Fig. S6). These results suggest that components associated with the cell envelope are involved in the ROS-enhancing activity of these 7 gram-negative bacteria. In contrast, extracellular components exhibited ROS-enhancing activity for 4 of the 6 gram-positive strains (Arthrobacter sp. BR2S-6, Bacillus sp. BR2R-4, Microbacterium sp. RS2P-3, and Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6) (Table 1 and Fig. S6). These results indicate that the bacterial components responsible for ROS-enhancing activity vary greatly between genera and species.

Comparative genomic analysis of Pseudomonas strains

We observed that some strains of gram-negative Pseudomonas enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells (Table 1), whereas other strains did not (Fig. S3). Assuming that the difference was at the genome level, we analyzed genetic features associated with the ROS-enhancing activity of the Pseudomonas strains by comparative genomic analysis. The genome sequences of 4 strains (BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, and RS3R-1) that enhanced ROS production (as shown in Table 1) have already been determined [35]. The genome sequence of strain RS3R-2, which did not enhance ROS production (Fig. S3), has also been determined [35]. Among the 10 Pseudomonas strains in the NBRC (NITE Biological Resource Center, Japan) culture collection for which the genomes have been sequenced, 3 strains (NBRC 13583, NBRC 14167, and NBRC 102411) did not enhance cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells (Fig. S7). We therefore performed a comparative genomic analysis of 4 strains that exhibited ROS-enhancing activity (BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, and RS3R-1) and 4 strains that did not exhibit such activity (RS3R-2, NBRC 13583, NBRC 14167, and NBRC 102411).

We identified 102 clusters of orthologous genes present in all ROS-enhancing strains that were absent in all non–ROS-enhancing strains (Table S2 and Fig. S8). These clusters were classified based on function (Fig. 5). Notably, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (M) was the most common category, which was consistent with the results of analyses indicating that ROS-enhancing components were associated with the cell envelope of gram-negative Pseudomonas strains (Table 1). In particular, COG0472 of category M corresponds to the gene wbpL (Table S2), which encodes a glycosyltransferase required for the synthesis of the O-specific antigen of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) in the outer cell envelope of Pseudomonas strains [36]. In addition, the gene clusters responsible for synthesis of the O-specific antigens of LPSs of the 8 Pseudomonas strains were analyzed using cblaster v1.3.8, a tool for identifying clusters of co-localized homologous sequences. We found differences in the structures of the gene clusters for LPS biosynthesis (the O-specific antigen gene clusters) including wbpL between strains that did and did not exhibit ROS-enhancing activity (Fig. 6). These results suggest that differences in the LPS structure play important roles in determining the ROS-enhancing activity of Pseudomonas strains.

Functional classification of clusters of orthologous genes present in all ROS-enhancing strains that were absent in all non–ROS-enhancing strains. Clusters of orthologous genes from the Pseudomonas genomes were listed, and the list was filtered by the clusters present in all strains that enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells (BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, and RS3R-1) but absent in all non–ROS-enhancing strains (RS3R-2, NBRC 13583, NBRC 14167, and NBRC 102411). The capital letters in x-axis indicates the COG categories as listed on the right of the histogram and the y-axis indicates the number of genes

Comparative analysis of gene clusters responsible for synthesis of the O-specific antigen of LPS in Pseudomonas strains using cblaster v1.3.8. Links between homologous genes are shown using specific colors. The gene cluster of P. aeruginosa PAO1, which has been well characterized [36], is shown for comparison

Discussion

Plant immunity–activating microorganisms have attracted considerable attention due to their ability to induce pathogen resistance. We previously established a method to directly detect microorganisms that activate the plant immune system by monitoring cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells as a marker of immune activation [27]. By applying this method to 31 bacterial endophytes isolated from B. rapa var. perviridis, 8 strains that enhance cryptogein-induced ROS production were obtained. Of these strains, Delftia sp. BR1R-2 and Arthrobacter sp. BR2S-6 induced whole-plant resistance to the bacterial pathogens P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082. We also found that pathogen-induced expression of plant defense-related genes was enhanced by pretreatment with strain BR1R-2 [27].

In this study, we first isolated endophytes from another Brassicaceae plant species, R. sativus var. hortensis. A total of 25 bacterial strains were isolated, of which 21 and 4 of the strains were classified as Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table S1). Bacterial endophytes are generally classified within 4 phyla: Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes [37, 38]. In our previous study, we found that 31 bacterial endophytes isolated from B. rapa var. perviridis belonged to 3 phyla, Proteobacteria (12 strains), Actinobacteria (8 strains), and Firmicutes (11 strains) [27]. In the present study, by contrast, no Firmicutes strains were isolated, and Proteobacteria strains dominated the isolated endophytes. The B. rapa var. perviridis and R. sativus var. hortensis plants used in these studies were grown using a similar method on the same farm, suggesting that the observed differences in the microbiome are partly due to differences in the host plants. However, other factors such as soil sampling time and soil conditions can also influence the microbiome. Sun and coworkers recently used a 16 S rRNA metagenomic approach to thoroughly probe the R. sativus microbiome [39]. They have reported that the dominant endophytic bacteria in R. sativus were Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinomycetes at the phylum level irrespective of cultivation conditions including greenhouse and open field cultivation. In Proteobacteria phylum, Pseudomonas, Brevundimonas, and Cellvibrio had higher abundances in R. sativus at the genus level [39]. In our present study, 21 strains were classified as Proteobacteria, and 11 of these Proteobacteria strains belonged to the genus Pseudomonas (Fig. 1). Pseudomonas strains have been isolated from R. sativus also in other studies [40, 41], suggesting that strains of this genus might play an important role in R. sativus.

The bacteria isolated from R. sativus var. hortensis were assayed for the ability to prime plant immune responses. Among the 25 strains of isolated bacteria, 6 strains markedly enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells (Fig. 2 and S3). Furthermore, each selected bacterial strain was inoculated into whole Arabidopsis plants before pathogen infection (Figs. 3 and 4). Strains RS3R-1 and RS1R-6 enhanced the resistance of Arabidopsis plants to challenges with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082, respectively. Furthermore, strain RS1P-1 enhanced the resistance of Arabidopsis plants to both pathogens. These results demonstrate that the assay method based on elicitor-induced ROS production in cultured plant cells is useful for identifying various types of microorganisms that activate plant defense responses. Although the other strains examined did not enhance the resistance of Arabidopsis to P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082, it is possible that these strains might enhance the resistance of other plant species to other pathogens.

We identified 2 Pseudomonas strains (RS1P-1 and RS3R-1) and 1 Rhodococcus strain (RS1R-6) that enhanced the pathogen resistance of plants (Fig. 4). Plant-associated bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas have been well-characterized to date [12, 14]. In addition to P. fluorescens WCS417r, which was described in the Introduction Section [15, 16], P. fluorescens CHA0, P. putida WCS358, and P. aeruginosa 7NSK2 reportedly trigger ISR in plants [42,43,44]. Additionally, a few strains of the genus Rhodococcus reportedly exhibit biocontrol activity. Rhodococcus erythropolis R138 prevents the bacterial pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum from infecting potato tubers by degrading a compound required for quorum sensing by this pathogen [45]. Rhodococcus sp. KB6, an endophytic bacterium isolated from Arabidopsis, enhances sweet potato resistance to black rot disease caused by Ceratocystis fimbriata [46]. Using cultured plant cells, in the present study, we confirmed that strains RS1P-1, RS3R-1, and RS1R-6 activate the plant immune system, and detailed characterizations of the biocontrol mechanisms of these strains are currently underway.

We also comprehensively investigated whether the plant immunity–activating components associated with the 14 bacterial strains derived from the 2 types of Brassicaceae plants were cellular or extracellular (Table 1). Notably, the cells of 7 of the 8 gram-negative strains enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells, but extracellular components produced by these strains did not (Table 1 and Fig. S6). Because intracellular bacterial components cannot make direct contact with plant cells, we hypothesized that the components responsible for the ROS-enhancing activity in these gram-negative bacteria are associated with the cell envelope. LPS is an abundant component of the outer cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria and is known to play important roles in triggering immune responses in plants [47]. LPS of Pseudomonas strains reportedly induces resistance to Fusarium wilt in carnation and radish [16, 48]. Furthermore, the results of a comparative genomic analysis supported the hypothesis that LPS plays an important role in enhancing ROS production by the gram-negative Pseudomonas strains examined in this study (Figs. 5 and 6). We found that all of the ROS-enhancing strains harbored the glycosyltransferase gene wbpL (COG0472), which mediates synthesis of the O-specific antigen of LPS, but this gene was not present in the non–ROS-enhancing strains (Fig. 5 and S8, Table S2). In addition, gene cluster analysis using the cblaster tool revealed that both the ROS-enhancing and non–ROS-enhancing strains differed greatly in terms of the structure of the gene cluster responsible for synthesis of the O-specific antigen of LPS (Fig. 6). The O-specific antigen is reportedly involved in the virulence of plant-pathogenic Pseudomonas strains [36]. Further investigations will therefore focus on gene deletion analysis. On the other hand, although the extracellular part (growth medium) of most of the Gram-negative bacteria did not trigger cryptogein-induced ROS production (Table 1), we cannot rule out the possibility that during interaction with plant cells, these bacteria might secrete some ROS-enhancing components.

With regard to gram-positive bacteria, the cells of Paenarthrobacter sp. BR3S-9 and Bacillus sp. BR2S-4 exhibited ROS-enhancing activity, but the extracellular components did not (Table 1 and Fig. S6), suggesting that cell envelope–associated components play a role in the ROS-enhancing activity of these strains as well. In contrast, in 4 of the 6 gram-positive strains (Arthrobacter sp. BR2S-6, Bacillus sp. BR2R-4, Microbacterium sp. RS2P-3, and Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6), extracellular components were found to enhance ROS production. The components produced by Arthrobacter sp. BR2S-6, Bacillus sp. BR2R-4, and Microbacterium sp. RS2P-3 were heat labile (Table 1), suggesting they could be proteins or peptides. Other studies have reported that proteins isolated from Bacillus strains can elicit plant immune responses [49, 50]. In contrast, characterization of the ROS-enhancing component produced by Rhodococcus sp. RS1R-6 revealed that it is heat stable (Table 1). Rhodococcus strains generally produce a variety of secondary metabolites [51], and thus, it is possible that the ROS-enhancing component produced by the strain in this study is a secondary metabolite.

Conclusion

An assay method based on elicitor-induced ROS production in cultured plant cells enabled the discovery of novel plant immunity–activating bacteria from R. sativus var. hortensis. Three strains that colonize the interior of Arabidopsis plants enhanced resistance to the bacterial pathogens P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and/or P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082. The results in this study also suggest that the bacterial components involved in the ROS-enhancing activity may differ markedly by genus and species, although larger number of bacterial strains need to be studied to confirm such theory. It is conceivable that bacteria of different genera and species evolved their own plant immunity–activating systems through exposure to the plant environment. Furthermore, our comparative genomic analysis demonstrated that the structure of LPS in the outer cell envelope may play an important role in the ROS-enhancing activity of gram-negative Pseudomonas strains.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of bacteria from the interior of R. sativus var. hortensis

Raphanus sativus var. hortensis plants were grown organically without the use of pesticides at the Suzuki Farm (Tachikawa, Tokyo, Japan) and collected in June 2019. Microorganisms were isolated from petioles and roots of the plants (Fig. S1) according to previous reports [22, 27], with some modifications: the fragments of petioles and roots were surface-sterilized by dipping in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, followed by immersion in 70% ethanol for 3–5 min. After rinsed with sterile water, each fragment was further cut and placed onto NBRC802 or ISP2 agar medium [27] and incubated at 30 °C for approximately 1 month. Taxonomic identification of the isolated bacteria was performed based on 16 S rRNA gene sequencing as reported previously [27, 52]. As the sequences of RS1R-3 and RS1R-4 were not successfully read using the primer 9 F [27], we used the primer 290 F (5′-CTGGTCTGAGAGGATGA-3′) instead.

Measurement of cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells after co-incubation with isolated bacteria

Cryptogein-induced ROS production was measured as reported previously [27]. In brief, the solution containing microbial cells and extracellular components (0.1 mL) was added to BY-2 cell suspension (60 g wet cell weight/L, 1.8 mL) in a well (3 mL) of a 6-well plate (Fig. S2). The mixture was incubated at room temperature on a rotary shaker (120 rpm) for 4 h. The cells were then collected by centrifugation (1000 rpm, 3 min) and suspended in fresh buffer to remove metabolites derived from microbial cells and BY-2 cells (e.g., organic compounds, ROS, and ROS scavengers). After addition of cryptogein (4–6 µM, 0.1 mL), the mixture was incubated at room temperature on a rotary shaker (120 rpm). ROS production induced by cryptogein was measured using a chemiluminescence assay with luminol. Samples that exhibited a relative chemiluminescence intensity more than 1.5 times that of mock-treated samples were selected as positives (Fig. 2 and S3). BY-2 cells preserved in our laboratory were used [27, 28].

Treatment of whole Arabidopsis plants with isolated bacteria

Whole Arabidopsis plants were treated with isolated bacteria as reported previously [27, 53, 54]. In brief, whole plants of Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 were inoculated with each strain of isolated bacteria by immersing the root tip of 7-day-old seedlings in diluted bacterial cell culture solution (OD600, 0.002) for 1 s. After inoculation, the plants were transferred to fresh 1/2 MS agar medium [27] and further cultivated in the growth chamber for 7 days. Seeds of A. thaliana Columbia-0 were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource.

Resistance of isolated bacteria-colonized Arabidopsis plants to bacterial pathogens was evaluated using P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 [53] and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum NBRC 14082 [55] as reported previously [27, 54]. In brief, pathogenic bacterial cell suspension (4 × 105 CFU/mL; 40 mL) was dispensed into 1/2 MS agar medium containing 14-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings. After the plates were incubated at room temperature for 2 min, the cell suspension was decanted, and the seedlings on the plates were rinsed with sterile water. The plates were then incubated in a growth chamber with a light intensity of 150–200 µE m− 2 s− 1 (16 h light/8 h dark) and temperature of 22 °C. Plant disease symptoms were observed at 4 days after infection.

Characterization of components enhancing cryptogein-induced ROS production

The bacterial cell culture solution was adjusted to an OD600 value of 0.8 using NBRC802 or ISP2 medium. To evaluate the thermal stability of the components, the bacterial cell culture solution was autoclaved. In contrast, to investigate the localization of the components, the bacterial cell culture solution was divided into cells and extracellular components by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 10 min). The supernatant was collected and used as extracellular components. The precipitated cells were suspended in the same volume of NBRC802 or ISP2 medium (OD600, 0.8). After the solutions were diluted by a factor of 10 using ROS assay buffer, they were subjected to the measurement of cryptogein-induced ROS production, as described above.

Comparative genomic analysis

Genome sequences of Pseudomonas strains BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, RS3R-1, and RS3R-2 were determined in our previous study [35]. In brief, for short-read sequencing, genomic libraries were prepared using a MGIEasy FS DNA Library Prep Set (MGI, Shenzhen, China), and sequencing was performed using a DNBSEQ-G400FAST sequencer and DNBSEQ-G400RS high-throughput rapid sequencing set (2 × 150 bp; MGI). The reads were utilized for de novo assembly using Platanus_B v1.3.2. Assembled genomes of Pseudomonas strains BR1R-3 (accession no. BSCL00000000), BR1R-5 (BSCO00000000), RS1P-1 (BSCP00000000), RS3R-1 (BSCQ00000000), and RS3R-2 (BSCR00000000) [35] and reference genomes of P. alcaliphila NBRC 102411 (accession no. BCZV00000000), P. oleovorans NBRC 13583 (BDAL00000000), and P. oleovorans NBRC 14167 (BDAJ00000000) were used for the comparative genomic analysis. Clusters of orthologous genes from these Pseudomonas genomes were listed using SonicParanoid with default parameter settings [56]. Subsequently, the list was filtered by the clusters present in all strains that enhanced cryptogein-induced ROS production in BY-2 cells (BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, and RS3R-1) but absent in all non–ROS-enhancing strains (RS3R-2, NBRC 13583, NBRC 14167, and NBRC 102411) [57]. Proteins were assigned to the clusters of orthologous genes using EggNOG-mapper v2.1.3 [58] with default parameters, based on the EggNOG 5.0 database [59]. A heatmap was created using TBtools v1.0986853 [60]. Genome sequences were searched for O-specific antigen gene clusters with the wbpL gene and its related genes of P. aeruginosa PAO1 [36] as a query using cblaster v1.3.8 [61] according to our previous report [62] with some modifications. Gene cluster comparison was visualized using clinker [63].

Data Availability

Data regarding the genomes of Pseudomonas strains BR1R-3, BR1R-5, RS1P-1, RS3R-1, and RS3R-2 were submitted to the NCBI GenBank and are publicly available under BioProject accession numbers PRJDB14730 and PRJDB14766. All other data generated during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Abbreviations

- CFU:

-

Colony forming unit

- ISR:

-

Induced systemic resistance

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

References

Jaiswal DK, Gawande SJ, Soumia PS, Krishna R, Vaishnav A, Ade AB. Biocontrol strategies: an eco-smart tool for integrated pest and diseases management. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22(1):324.

Timmusk S, Behers L, Muthoni J, Muraya A, Aronsson AC. Perspectives and Challenges of Microbial Application for Crop Improvement. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:49.

Liu H, Carvalhais LC, Crawford M, Singh E, Dennis PG, Pieterse CMJ, Schenk PM. Inner plant values: diversity, colonization and benefits from endophytic Bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2552.

Oukala N, Aissat K, Pastor V. Bacterial endophytes: the hidden actor in Plant Immune responses against biotic stress. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(5):1012.

Dangl JL, Jones JD. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature. 2001;411(6839):826–33.

Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444(7117):323–9.

Bigeard J, Colcombet J, Hirt H. Signaling mechanisms in pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). Mol Plant. 2015;8(4):521–39.

Peng Y, van Wersch R, Zhang Y. Convergent and divergent signaling in PAMP-Triggered immunity and effector-triggered immunity. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2018;31(4):403–9.

Ramirez-Prado JS, Abulfaraj AA, Rayapuram N, Benhamed M, Hirt H. Plant Immunity: from signaling to Epigenetic Control of Defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23(9):833–44.

van Loon LC, Bakker PA, Pieterse CM. Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36:453–83.

Kloepper JW, Ryu CM, Zhang S. Induced systemic resistance and Promotion of Plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology. 2004;94(11):1259–66.

Pieterse CMJ, Van Wees SCM, Ton J, Van Pelt JA, Van Loon LC. Signalling in rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. 2002;4:535–44.

Shafi J, Tian H, Ji M. Bacillus species as versatile weapons for plant pathogens: a review. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2017;31(3):446–59.

Van Wees SC, Van der Ent S, Pieterse CM. Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11(4):443–8.

Pieterse CM, van Wees SC, van Pelt JA, Knoester M, Laan R, Gerrits H, Weisbeek PJ, van Loon LC. A novel signaling pathway controlling induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10(9):1571–80.

van Peer R, Niemann GJ, Schippers B. Induced resistance and phytoalexin accumulation in biological control of fusarium wilt of carnation by Pseudomonas sp. strain WCS417r. Phytopathology. 1991;81(7):728–34.

Nie P, Li X, Wang S, Guo J, Zhao H, Niu D. Induced systemic resistance against Botrytis cinerea by Bacillus cereus AR156 through a JA/ET- and NPR1-Dependent signaling pathway and activates PAMP-Triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:238.

Niu DD, Liu HX, Jiang CH, Wang YP, Wang QY, Jin HL, Guo JH. The plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus cereus AR156 induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by simultaneously activating salicylate- and jasmonate/ethylene-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24(5):533–42.

Reinhold-Hurek B, Hurek T. Living inside plants: bacterial endophytes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14(4):435–43.

Ryan RP, Germaine K, Franks A, Ryan DJ, Dowling DN. Bacterial endophytes: recent developments and applications. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;278(1):1–9.

Conn VM, Walker AR, Franco CM. Endophytic actinobacteria induce defense pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21(2):208–18.

Coombs JT, Franco CM. Isolation and identification of actinobacteria from surface-sterilized wheat roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(9):5603–8.

Esmaeel Q, Miotto L, Rondeau M, Leclère V, Clément C, Jacquard C, Sanchez L, Barka EA. Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN-Plants Interaction: from perception to the Induced Mechanisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2093.

Timmermann T, Armijo G, Donoso R, Seguel A, Holuigue L, González B. Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN protects Arabidopsis thaliana against a virulent strain of Pseudomonas syringae through the activation of Induced Resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2017;30(3):215–30.

Fujita M, Kusajima M, Okumura Y, Nakajima M, Minamisawa K, Nakashita H. Effects of colonization of a bacterial endophyte, Azospirillum sp. B510, on disease resistance in tomato. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2017;81(8):1657–62.

Kusajima M, Shima S, Fujita M, Minamisawa K, Che FS, Yamakawa H, Nakashita H. Involvement of ethylene signaling in Azospirillum sp. B510-induced disease resistance in rice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2018;82(9):1522–6.

Kurokawa M, Nakano M, Kitahata N, Kuchitsu K, Furuya T. An efficient direct screening system for microorganisms that activate plant immune responses based on plant-microbe interactions using cultured plant cells. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7396.

Kurusu T, Higaki T, Kuchitsu K. Programmed cell death in plant immunity: cellular reorganization, signaling and cell cycle dependence in cultured cells as a model system. In: Plant programmed cell death. (ed. Gunawardena A, McCabe P) 2015;77–96 (Springer).

Kadota Y, Fujii S, Ogasawara Y, Maeda Y, Higashi K, Kuchitsu K. Continuous recognition of the elicitor signal for several hours is prerequisite for induction of cell death and prolonged activation of signaling events in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47(9):1337–42.

Kadota Y, Goh T, Tomatsu H, Tamauchi R, Higashi K, Muto S, Kuchitsu K. Cryptogein-induced initial events in tobacco BY-2 cells: pharmacological characterization of molecular relationship among cytosolic Ca2+ transients, anion efflux and production of reactive oxygen species. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45(2):160–70.

Kadota K, Kuchitsu K. Regulation of elicitor-induced defense responses by Ca2+ channels and cell cycle in tobacco BY-2 cells. Biotechnol Agric For. 2006;58:207–21.

Kadota Y, Watanabe T, Fujii S, Higashi K, Sano T, Nagata T, Hasezawa S, Kuchitsu K. Crosstalk between elicitor-induced cell death and cell cycle regulation in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant J. 2004;40(1):131–42.

Kadota Y, Watanabe T, Fujii S, Maeda Y, Ohno R, Higashi K, Sano T, Muto S, Hasezawa S, Kuchitsu K. Cell cycle dependence of elicitor-induced signal transduction in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46(1):156–65.

Higaki T, Kurusu T, Hasezawa S, Kuchitsu K. Dynamic intracellular reorganization of cytoskeletons and the vacuole in defense responses and hypersensitive cell death in plants. J Plant Res. 2011;124(3):315–24.

Kaneko H, Furuya T. Draft genome sequences of endophytic Pseudomonas strains, isolated from the interior of Brassicaceae plants. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2023;12(4):e0133722.

Kutschera A, Schombel U, Wröbel M, Gisch N, Ranf S. Loss of wbpL disrupts O-polysaccharide synthesis and impairs virulence of plant-associated Pseudomonas strains. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20(11):1535–49.

Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, van Ver Loren E, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:807–38.

Hardoim PR, van Overbeek LS, Berg G, Pirttilä AM, Compant S, Campisano A, Döring M, Sessitsch A. The Hidden World within plants: ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of Microbial Endophytes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2015;79(3):293–320.

Sun N, Gu Y, Jiang G, Wang Y, Wang P, Song W, Ma P, Duan Y, Jiao Z. Bacterial Communities in the Endophyte and Rhizosphere of White Radish (Raphanus sativus) in different compartments and growth conditions. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:900779.

Rodriguez P, Magallanes-Noguera C, Menéndez P, Orden AA, Gonzalez D, Kurina-Sanz M, Rodríguez S. A study of Raphanus sativus and its endophytes as carbonyl group bioreducing agents. Biocatal Biotransform. 2015;33(2):121–9.

Seo WT, Lim WJ, Kim EJ, Yun HD, Lee YH, Cho KM. Endophytic bacterial diversity in the young radish and their antimicrobial activity against pathogens. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2010;53(4):493–503.

De Vleesschauwer D, Cornelis P, Höfte M. Redox-active pyocyanin secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2 triggers systemic resistance to Magnaporthe grisea but enhances Rhizoctonia solani susceptibility in rice. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19(12):1406–19.

Iavicoli A, Boutet E, Buchala A, Métraux JP. Induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana in response to root inoculation with Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16(10):851–8.

Meziane H, VAN DER Sluis I, VAN Loon LC, Höfte M, Bakker PA. Determinants of Pseudomonas putida WCS358 involved in inducing systemic resistance in plants. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6(2):177–85.

Barbey C, Crépin A, Bergeau D, Ouchiha A, Mijouin L, Taupin L, Orange N, Feuilloley M, Dufour A, Burini JF, Latour X. In Planta Biocontrol of Pectobacterium atrosepticum by Rhodococcus erythropolis involves silencing of Pathogen Communication by the Rhodococcal Gamma-Lactone Catabolic Pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66642.

Hong CE, Jeong H, Jo SH, Jeong JC, Kwon SY, An D, Park JM. A Leaf-Inhabiting Endophytic Bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. KB6, enhances Sweet Potato Resistance to Black Rot Disease caused by Ceratocystis fimbriata. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26(3):488–92.

Shang-Guan K, Wang M, Htwe NMPS, Li P, Li Y, Qi F, Zhang D, Cao M, Kim C, Weng H, Cen H, Black IM, Azadi P, Carlson RW, Stacey G, Liang Y. Lipopolysaccharides trigger two successive bursts of reactive oxygen species at distinct Cellular locations. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(3):2543–56.

Leeman M, van Pelt JA, den Ouden FM, Heinsbroek M, Bakker PAHM, Schippers B. Induction of systemic resistance against Fusarium wilt of radish by lipopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopathology. 1995;85(9):1021–7.

Wang N, Liu M, Guo L, Yang X, Qiu D. A Novel protein elicitor (PeBA1) from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NC6 induces systemic resistance in Tobacco. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12(6):757–67.

Shen Y, Li J, Xiang J, Wang J, Yin K, Liu Q. Isolation and identification of a novel protein elicitor from a Bacillus subtilis strain BU412. AMB Express. 2019;9(1):117.

Cappelletti M, Presentato A, Piacenza E, Firrincieli A, Turner RJ, Zannoni D. Biotechnology of Rhodococcus for the production of valuable compounds. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104(20):8567–94.

Ishida A, Furuya T. Diversity and characteristics of culturable endophytic bacteria from Passiflora edulis seeds. MicrobiologyOpen. 2021;10(4):e1226.

Ishiga Y, Ishiga T, Ichinose Y, Mysore KS. Pseudomonas syringae Flood-inoculation Method in Arabidopsis. Bio Protoc. 2017;7(2):e2106.

Ishiga Y, Ishiga T, Uppalapati SR, Mysore KS. Arabidopsis seedling flood-inoculation technique: a rapid and reliable assay for studying plant-bacterial interactions. Plant Methods. 2011;7:32.

Seo ST, Furuya N, Lim CK, Takanami Y, Tsuchiya K. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of Erwinia carotovora from mulberry (Morus spp). Plant Pathol. 2003;52:140–6.

Cosentino S, Iwasaki W. SonicParanoid: fast, accurate and easy orthology inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(1):149–51.

Vogel CM, Potthoff DB, Schäfer M, Barandun N, Vorholt JA. Protective role of the Arabidopsis leaf microbiota against a bacterial pathogen. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(12):1537–48.

Cantalapiedra CP, Hernández-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, Orthology assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(12):5825–9.

Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Heller D, Hernández-Plaza A, Forslund SK, Cook H, Mende DR, Letunic I, Rattei T, Jensen LJ, von Mering C, Bork P. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D309–14.

Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative Toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202.

Gilchrist CL, Booth TJ, van Wersch B, van Grieken L, Medema MH, Chooi YH. cblaster: a remote search tool for rapid identification and visualization of homologous gene clusters. Bioinf Adv. 2021;1(1):vbab016.

Tonegawa S, Ishii K, Kaneko H, Habe H, Furuya T. Discovery of diphenyl ether-degrading Streptomyces strains by direct screening based on ether bond-cleaving activity. J Biosci Bioeng. 2023;135(6):474–9.

Gilchrist CL, Chooi YH. Clinker & clustermap.js: automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics. 2021;18(37):2473–5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. F. Katagiri and Dr. H. Takagi (University of Minnesota) for providing P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. This strain was imported under a permit from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan, in accordance with the Plant Protection Law. We thank Suzuki Farm (Tachikawa, Tokyo, Japan) for the gift of R. sativus var. hortensis. We thank Dr. N. Kitahata, Dr. M. Nakano, and Dr. S. Hanamata for helpful advice and technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. 20K05812), a grant from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (IFO), and a grant from the Nagase Science and Technology Foundation. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K., K.K., and T.F. conceived and designed the research. H.K. and F.M. performed the experiments. M.K., K.H., K.K., and T.F. directed the research. H.K., K.K., and T.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not involve humans or animals, and therefore, no human or animal data were collected. All the methods involving the plant and its material complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaneko, H., Miyata, F., Kurokawa, M. et al. Diversity and characteristics of plant immunity–activating bacteria from Brassicaceae plants. BMC Microbiol 23, 175 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-02920-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-02920-y