Abstract

Background

The tsetse fly (Glossina sp.) midgut is colonized by maternally transmitted and environmentally acquired bacteria. Additionally, the midgut serves as a niche in which pathogenic African trypanosomes reside within infected flies. Tsetse’s bacterial microbiota impacts many aspects of the fly’s physiology. However, little is known about the structure of tsetse’s midgut-associated bacterial communities as they relate to geographically distinct fly habitats in east Africa and their contributions to parasite infection outcomes. We utilized culture dependent and independent methods to characterize the taxonomic structure and density of bacterial communities that reside within the midgut of tsetse flies collected at geographically distinct locations in Kenya and Uganda.

Results

Using culture dependent methods, we isolated 34 strains of bacteria from four different tsetse species (G. pallidipes, G. brevipalpis, G. fuscipes and G. fuscipleuris) captured at three distinct locations in Kenya. To increase the depth of this study, we deep sequenced midguts from individual uninfected and trypanosome infected G. pallidipes captured at two distinct locations in Kenya and one in Uganda. We found that tsetse’s obligate endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia, was the most abundant bacterium present in the midgut of G. pallidipes, and the density of this bacterium remained largely consistent regardless of whether or not its tsetse host was infected with trypanosomes. These fly populations also housed the commensal symbiont Sodalis, which was found at significantly higher densities in trypanosome infected compared to uninfected flies. Finally, midguts of field-captured G. pallidipes were colonized with distinct, low density communities of environmentally acquired microbes that differed in taxonomic structure depending on parasite infection status and the geographic location from which the flies were collected.

Conclusions

The results of this study will enhance our understanding of the tripartite relationship between tsetse, its microbiota and trypanosome vector competence. This information may be useful for developing novel disease control strategies or enhancing the efficacy of those already in use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) are medically and agriculturally important insect vectors that transmit African trypanosomes, the causative agents of human and animal African trypanosomiases (HAT and AAT, respectively). Approximately 70 million people, living within an area of 1.55 million km2 in sub-Saharan Africa, are at risk for contracting HAT, which is almost always fatal if left untreated [1]. Additionally, AAT is estimated to cost African agriculture US$4.5 billion per year [2]. Disease preventing vaccines are currently unavailable due to the fact that trypanosomes continuously switch their antigenically distinct Variant Surface Glycoprotein coat to evade the mammalian host immune system [3]. Furthermore, drug resistance in parasites is increasing and can compromise the efficacy of treating infected patients chemotherapeutically [4]. Disease can be effectively controlled by reducing tsetse population densities during disease outbreaks. However, these practices are costly and labor-intensive and often rely on insecticide-treated devices or aerial sprays, which are environmentally unfriendly. Thus, novel disease control strategies, including those designed to reduce tsetse’s ability to transmit trypanosomes, can provide desirable cost-effective alternatives.

While only a small percentage of field-captured tsetse are infected with trypanosomes (reviewed in [5]), all individuals house enteric communities of indigenous, maternally transmitted symbiotic bacteria as well as bacteria acquired from the environment [6, 7]. Obligate Wigglesworthia [8] and commensal Sodalis [9] are vertically transmitted via maternal milk gland secretions to developing intrauterine larvae during tsetse’s unique viviparous mode of reproduction [10]. Wigglesworthia is found in all lab colonized and field-captured tsetse flies, and its symbiosis with the fly is ancient [11]. Female flies experimentally reared in the absence of obligate Wigglesworthia (via dietary supplementation of the blood meal with antibiotics) cannot support larval development and thus become reproductively sterile [12, 13]. Wigglesworthia’s genome encodes biochemical pathways responsible for the production of vitamins and co-factors that the fly cannot produce de novo and that are absent from its vertebrate blood-specific diet [14]. Correspondingly, metabolomic analyses [15] and dietary supplementation studies [16] indicate that loss of fecundity in symbiont-cured females results from decreased levels of essential nutrients (in particular B-Vitamins) that are necessary for tsetse to produce amino and nucleic acids. Obligate Wigglesworthia also mediates the development and function of its host’s immune system. Specifically, larvae that undergo development in the absence of this bacterium present a compromised cellular immune system as adults [17,18,19] and are unusually susceptible to infection with trypanosomes [20].

In contrast to Wigglesworthia, tsetse’s symbiosis with commensal Sodalis is relatively recent, and this bacterium can be cultured outside of tsetse and genetically modified [21]. These characteristics make Sodalis amenable as a potential candidate for paratransgenic control of trypanosome transmission [22]. While Sodalis’ functional contribution to tsetse’s physiology is currently unknown, specific elimination of the bacterium from the fly results in a reduction in fly longevity [23]. Furthermore, Sodalis mediates tsetse’s susceptibility to infection with trypanosomes [24], and some field-based studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between the presence of Sodalis, and/or high Sodalis density, and parasite infection prevalence [7, 25,26,27]. Understanding factors that contribute to trypanosome infections in susceptible flies can lead to new vector control methods that are based on increasing parasite resistance phenotypes in natural population. Along with host genetic factors (such as hostile immune responses) that influence transmission dynamics, microbiota also influence pathogen transmission in vector insects, including tsetse [28].

In addition to maternally transmitted symbionts, wild tsetse flies also harbor a variety of environmentally-acquired bacteria in their guts. The taxonomic composition and density of these bacterial populations varies significantly within and between sympatric populations of tsetse composed of the same or different species. However, members of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicuties and Beta- and Gamma-proteobacteria are found consistently within the gut of different tsetse species captured in geographically distinct locales [7, 29,30,31]. In most cases these transient microbes comprise less than 1% of tsetse’s cumulative enteric microbiota [7]. The origin of environmentally-acquired gut microbes, and their function as they relate to the physiology of their tsetse host, remains to be elucidated. In this study we employed culture dependent and independent methods in an effort to better define the core population of environmentally acquired bacteria that reside in the midgut of field-captured tsetse. Additionally, we investigated whether the taxonomic composition and relative abundance of distinct bacterial taxa correlates with environmental conditions and trypanosome infection status.

Results

Glossina collections

One-hundred and ninety-three tsetse flies, representing four species (G. pallidipes, n = 165; G. fuscipes, n = 4; G. fusciplures, n = 12; G. brevipalpis, n = 12) collected from five sites (Table 1), were used for this study. Of the 193 flies, 20 individuals representing four species (G. pallidipes, n = 11; G. fuscipes, n = 3, G. fusciplures, n = 3; G. brevipalpis, n = 3) were used to culture midgut bacteria in vitro (Table 1). All other experiments were performed using only G. pallidipes, of which 112 were used for culture independent characterization of midgut microbiota (Table 1), and 41 (21 trypanosome infected and 20 uninfected, as determined by microscopic analysis) were used to assess the correlation between symbiont density and trypanosome infection status.

Bacterial taxa cultured from the fly gut

Twenty-four fly midguts were subjected to identical bacterial isolation processes, and 20 (11 G. pallidipes, 3 G. brevipalpis, 3 G. fuscipleuris and 3 G. fuscipes) yielded culturable bacterial clones. Between one and four bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were identified from each fly, and 34 bacterial OTUs were isolated in total (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). The 16S rRNA gene from all 34 isolates was amplified and sequenced. Following the sequence alignment, members of 14 different genera were identified (Table 2). The most common isolate was Bacillus sp., which was identified from 10 (50.0%) individuals. Both Bacillus and Staphylococcus were isolated from individuals in all three collection sites. G. fuscipleuris collected in Trans Mara, Kenya had the greatest number of genera represented (6), while only one genus was isolated from Shimba Hills G. brevipalpis. Of the 20 flies examined, 10 housed one culturable OTU, while 10 housed two or more (Table 2).

Out of the 34 isolates, 21 belonged to the phylum Firmicutes, 6 to Proteobacteria and 7 to Actinobacter. With the exception of G. brevipalpis, in which only one bacterial genus was found, representative isolates of the above three phyla were found in each tsetse species (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Tsetse gut-associated microbes identified via culture independent methods

To better define the population of bacteria that reside transiently in tsetse’s midgut, we used PCR to generate barcoded 16S rDNA libraries from 112 G. pallidipes midguts. These libraries were subsequently pooled and deep sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. A total of 21,728,153 reads were obtained from the 112 samples. After quality filtering, a total of 16,635,470 sequences were obtained (average 148,531 sequences per sample) and entered into the QIIME software pipeline for alignment and taxonomic assignment.

Midgut microbial diversity across multiple G. pallidipes populations

Using 16 s rDNA deep sequencing, we identified bacterial OTUs within individual G. pallidipes trapped in Nguruman, Shimba Hills and Murchison Falls. Figure 1 presents three sets of graphs, each of which shows data from one of the different trapping sites. Individual bacterial OTUs are indicated as % abundance of the total population present in each individual fly gut. Wigglesworthia and Sodalis are presented on the bottom graph, while the top graph presents the next six most abundant environmentally acquired bacteria (averaged across samples and excluding Wigglesworthia and Sodalis). Results are presented in this manner in an effort to better visualize the community of exogenous, environmentally acquired bacteria detected in the gut of G. pallidipes collected from ecologically distinct habitats. In a previous study we found that Wigglesworthia represented > 99% of the total bacteria found in the midgut of G. fuscipes captured in Murchison Falls [7]. In an effort to more completely resolve the population of environmental bacteria found in the midgut of G. pallidipes used in this study, we treated the 16 s rDNA amplicons with EcoRV to remove Wigglesworthia-specific sequences. As such, % abundance data presented here excludes Wigglesworthia sequences removed by this treatment.

Taxonomic composition and % abundance of bacteria found in midguts of uninfected and trypanosome infected G. pallidipes caught in Nguruman, Kenya, Shimba Hills, Kenya and Murchison Falls, Uganda. Data collected from each location is exhibited on two graphs. The top and bottom graphs show the % abundance of total midgut bacteria that are composed of environmentally acquired and maternally transmitted OTUs, respectively. Individual flies assayed from each site are represented by a distinct bar on each graph

At Nguruman Escarpment in south-central Kenya, the 6 most abundant environmentally acquired taxa were comprised of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (including the genera Enterobacter and Serratia), as well as members from the genera Pseudoxanthomonas, Cloacibacterium,and Sphingobacterium. In G. pallidipes captured on the Kenya’s east coast in Shimba Hills National park, the bacterial population was represented by members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (including the genus Serratia) and members from the genera Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas and Cloacibacterium. Finally, the 6 most abundant environmentally acquired taxa found in guts of G. pallidipes collected in Murchison Falls, Uganda included members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (including the genus Serratia) as well as members from the genera Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter, Anaerococcus and Enhydrobacter (Fig. 1).

In addition to characterizing the population of environmentally acquired bacteria that reside in field-captured G. pallidipes, we also used our deep-sequencing reads as a source of data to quantify the density of maternally transmitted symbionts found in these flies. At all three trapping locations, obligate Wigglesworthia represented the majority of bacterial OTUs by % abundance in all individuals (Nguruman, 91.99%; Shimba Hills, 76.67%; Murchison Falls, 90.26%; Fig. 1). Sodalis, a commensal tsetse symbiont, comprised an average of 2.37%, 23.05% and 8.09% of the total bacteria present in G. pallidipes sampled in Nguruman, Shimba Hills and Murchison Falls, respectively (Fig. 1). The averages for each sampling site, also presented as % of total bacterial abundance, are displayed in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Diversity measures

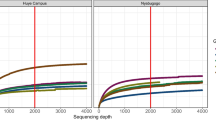

We used the “observed species” metric to measure α-diversity (species richness) of bacteria found in guts of G. pallidipes collected from all three sites. The rarefaction curve leveled off at 6000 sequences per sample, indicating that an adequate sequencing depth and OTU discovery was achieved (Fig. 2a). At a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), we observed statistically significant differences in α-diversity between one of the three study sites (Fig. 2b). Specifically, Shimba Hills had the lowest species richness (mean OTUs, 12.38 ± 2.45), which was statistically significant different from Nguruman (mean OTUs, 25.05 ± 17.11; p = 0.024). Shimba Hills was not significantly different from Murchison Falls (mean OTUs, 25.5 ± 28.73; p = 0.261), and Murchison Falls and Nguruman were not significantly different from each other (p = 1; Fig. 2b).

Measurement of bacterial α and β-diversity in midguts of G. pallidipes captured in Shimba Hills, Nguruman and Murchison Falls. Plots (a) and (b) present bacterial α-diversity (indicative of species richness), which was measured using the ‘observed species metric’. a Rarefaction curves demonstrate the analysis achieved adequate sequencing depth and OTU discovery. b At a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), a statistically significant difference in species richness was observed between flies collected from Shimba Hills vs. Murchison Falls (p = 0.024). Plot (b) shows bacterial β-diversity measured using the unweighted UniFrac metric and Bray Curtis method. c Average UniFrac distance within each collection site (left graph) and between each collection site (right graph). β-diversity was statistically significantly different between G. pallidipes captured in Shimba Hills and Murchison Falls (nonparametric paired t-test; p = 0.028). β-diversity between the other two sites was not significantly different at a 95% confidence level

We next used the unweighted UniFrac metric, and the Bray Curtis method, to measure β-diversity of bacteria within and between G. pallidipes individuals collected at the three geographic regions. Figure 2c displays the average UniFrac distance within each collection site (left graph) and between each collection site (right graph). Using a nonparametric paired t-test, significant differences in the β-diversity among the G. pallidipes flies trapped in Shimba Hills and Murchison Falls (p = 0.028) were observed. The β-diversity of the other two sites was not significantly different at a 95% confidence level.

Tsetse’s microbiota and trypanosome infection status

The gut microbiota of arthropod disease vectors influences their host’s capacity to transmit pathogenic microorganisms [28, 32, 33]. In tsetse, the obligate mutualist Wigglesworthia plays important roles in defining the ability of trypanosomes to establish an infection in tsetse’s gut. More specifically, this bacterium mediates the production of trypanocidal Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein LB (PGRP-LB) [34] as well as the development and function of a midgut barrier called the peritrophic matrix [20]. A correlative relationship also exists between the presence of Sodalis and increased susceptibility of tsetse to infection with trypanosomes (reviewed in [6]), although the mechanistic basis of this interaction remains unknown.

Herein we compared the taxonomic structure of bacterial communities that reside in guts of trypanosome uninfected versus infected G. pallidipes captured in Shimba Hills, Nguruman and Murchison Falls. To do so we separated our cumulative 16S data from all 3 locations (displayed in Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Figure S1) into uninfected and trypanosome infected pools, and then averaged the density of the six most abundant environmentally acquired microbes, as well as Wigglesworthia and Sodalis, found in each of the pools. With respect to environmentally acquired enteric bacteria, Serratia spp. were dominant in parasite infected G. pallidipes collected in Nguruman, and in both uninfected and infected individuals from Shimba Hills. Additionally, other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae were also found in relatively high numbers in uninfected flies from both of these locations, and in parasite infected flies from Shimba Hills (Fig. 3a, top graphs). Unlike their counterparts found in Nguruman and Shimba Hills, G. pallidipes captured in Murchison Falls housed mainly ‘other’ bacteria (could not be resolved to family level) in their guts, regardless of trypanosome infection status (Fig. 3a, top graphs).

Average taxonomic composition and % abundance of environmentally acquired and symbiotic bacteria found in midguts of uninfected and trypanosome infected G. pallidipes captured in Nguruman, Kenya, Shimba Hills, Kenya and Murchison Falls, Uganda. a Community structure of environmentally acquired bacteria (top set of graphs), and maternally transmitted symbionts (bottom set of graphs), identified from midguts of field-captured G. pallidipes. Data on the top and bottom graphs are presented as % abundance of the total (100%) bacterial population present in trypanosome uninfected and infected flies from each geographic location. The range of values on the Y-axes on the bottom set of graphs (maternally transmitted symbionts) is different so that low density Sodalis populations are visible. b Real-time quantitative PCR-based determination of Wigglesworthia and Sodalis densities in uninfected (UF) and trypanosome infected (IF) G. pallidipes trapped in Nguruman and Shimba Hills. Sample data derived from uninfected and parasite infected flies captured at each location was pooled so as to present an overall picture of the relationship between symbiont density and trypanosome infection status. Statistical significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism software, v. 7

‘Similarity’ tests, performed to take into account both weighted (takes into account species abundance) and unweighted (takes into account bacterial taxonomic structure) distance matrices, indicated that the taxonomic composition of environmentally acquired enteric microbes was significantly different between trypanosome infected and uninfected G. pallidipes collected in Shimba Hills (unweighted p-value = 0.01, R = 0.55; weighted p-value = 0.02, R = 1). Conversely, the taxonomic composition of environmentally acquired enteric microbes was not significantly different between trypanosome infected and uninfected G. pallidipes collected in Nguruman (unweighted p-value = 0.14, R = 0.14; weighted p-value = 071, R = − 0.16) nor Murchison Falls (unweighted p-value = 0.64, R = − 0.09; weighted p-value = 0.08, R = 0.41). Taken together, these findings suggest that the taxonomic structure and density of environmentally acquired enteric bacteria differs based on whether or not the host fly harbors an infection with trypanosomes. A more robust analysis, making use of a larger population of infected flies, is required in order to definitively correlate the taxonomic structure of environmentally acquired enteric bacteria with trypanosome infections outcomes in field-captured tsetse.

We next used the 16S rDNA data to investigate the relationship between symbiont density and trypanosome infection status. As expected we found that Wigglesworthia comprised the majority of bacterial taxa present in guts of uninfected and infected G. pallidipes from all three sites (Fig. 3a, bottom graphs). Interestingly, we observed that Sodalis was more abundant in guts of uninfected flies compared to trypanosome infected individuals captured in all three locations (Fig. 3a, bottom graphs). These findings contradict those from previous studies, which correlate high Sodalis density with increased trypanosome infection prevalence [25,26,27]. We thus investigated this finding in more depth by using real-time quantitative PCR to determine the density of Wigglesworthia and Sodalis in a larger sample size of trypanosome uninfected and infected G. pallidipes. We did not have any infected flies remaining from Murchison Falls, hence this experiment was performed with individuals collected in Nguruman and Shimba Hills. When the data from the two sites was combined, we observed no significant difference in the Wigglesworthia density between uninfected and infected individuals. However, Sodalis was significantly more abundant in trypanosome infected flies compared to their uninfected counterparts (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

In the present study we used culture dependent and independent methods to characterize the enteric microbiota found in tsetse flies, collected from three geographically and environmentally distinct locations, in an effort to better understand their contributions to tsetse’s vector competence. Culture dependent analysis demonstrated that specific bacterial taxa resident within tsetse’s midgut can be grown in vitro using previously described methods [31]. Further, more rigorous analysis using next-generation sequencing technology revealed that bacterial taxa present in the midgut of one tsetse species, G. pallidipes, varied depending on the site at which flies were collected. This habitat-based variation in microbiota composition was reflected in the abundance of both maternally transmitted obligate and commensal symbionts as well as environmentally acquired bacteria. Additionally, clear differences were present in the density and taxonomic composition of bacteria found in guts of trypanosome infected compared to uninfected flies of the same Glossina species collected from the same location. Overall, these results suggest that the environment in which tsetse reside plays an important role in the composition of the fly’s midgut microbiome. Furthermore, the composition of tsetse’s midgut microbiota may relate to the fly’s ability to transmit pathogenic African trypanosomes. Additional research is required to determine the role of maternally transmitted and environmentally acquired bacteria as they relate to the physiology of their tsetse host.

In this study, 34 bacterial isolates were successfully cultured, of which 21 belonged to the phylum Firmicutes, six to Proteobacteria and seven to Actinobacter. With the exception of G. brevipalpis, from which only one bacterial genus was cultured, representative isolates of the above three phyla were found in each tsetse species. Both Bacillus and Staphylococcus were isolated from individuals in all three collection sites. In this study, Firmicutes and Bacillus were the dominant phylum and genus, respectively. Three previous studies [29,30,31] have employed culture dependent methods to investigate the microbial composition of tsetse midguts from fly populations geographically distinct from the ones used here in. Bacterial strains from the Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Actinobacter were identified in each case, although the dominant phyla observed in each study was variable. This variability could be due to the fact that different culture conditions were utilized in each case. In this study three different types of media were tested, and all samples were grown at room temperature in anaerobic and ambient oxygen concentrations. Thus, it appears as though the diversity and relative abundance of microbes that can be cultured from tsetse’s gut depends upon several factors, including the environment in which the fly lives as well as the conditions in which the isolates were grown. Further studies that engage different culture conditions should be performed in an effort to identify additional culturable bacteria from the tsetse fly gut. These bacteria may be of particular importance because they can potentially be genetically modified and/or trans-located between tsetse species or between field-captured flies and insectary-reared individuals that harbor a different microbiota. Such taxa may be useful for performing functional experiments that will provide insight into how tsetse’s microbiota modifies their host’s physiology, including trypanosome vector competence. Additionally, culturable isolates may serve as candidates in a control strategy in which tsetse are colonized with recombinant bacteria that express anti-trypanosomal effector molecules. These ‘paratransgenic’ flies could exhibit a reduced ability to successfully transmit parasites between mammalian hosts [22, 35, 36].

Previous experiments performed to characterize tsetse’s midgut microbiome have lacked the illustrative power of comparing culture dependent and independent analyses in the same study population. This experimental shortcoming is important for two reasons. First, it fails to address what proportion of the total bacterial population is represented by culturable organisms. Secondly, it does not allow for the identification of taxa that cannot be cultured under the specific experimental conditions used in the study. As such, the vast majority of bacteria present in the niche are left unidentified. Recently, deep sequencing technology, based on the Illumina MiSeq platform, was used in an attempt to acquire a more in-depth overview of the microbiota found in guts of tsetse collected in Uganda [7]. This study successfully revealed that tsetse does house a more taxonomically complex gut microbiota than that identified via culture dependent methods and 16 s rRNA clone libraries. However, determining a comprehensive picture of the population structure of environmentally acquired microbes present in samples from the Ugandan study was likely obfuscated by the fact that obligate Wigglesworthia represented greater than 99% of the cumulative OTUs observed. This impediment was partially circumvented in this study by digesting Wigglesworthia-specific V4 PCR products with EcoRV endonuclease prior to library sequencing. This treatment succeeded in eliminating a significant proportion of Wigglesworthia reads (14.0% of total OTUs), thus allowing for a more comprehensive view of other microbial taxa resident in tsetse midguts analyzed in this study.

Results from this study indicate that adult tsetse flies house a taxonomically complex population of bacteria in their gut. The biological mechanisms that underlie colonization of tsetse’s midgut by environmental bacteria requires further investigation. However, the dynamics of this process are presumably different from that which occurs in other well-studied insect models. For example, free-living larval fruit flies and mosquitoes acquire nutrients directly from in their resident environment, which is rotting organic matter and fetid water, respectively. As such, immature stages of these insects house a robust gut microbiota [37,38,39]. Conversely, immature tsetse undergo their entire larval development within their mother’s uterus. This environment is devoid of environmental microbes, and during this time larvae are exposed exclusively to low densities of maternally-transmitted Wigglesworthia, Sodalis and in some cases Wolbachia [40]. Tsetse flies acquire food from their environment only during the adult stage of their lifecycle. Following eclosion teneral adults seek a vertebrate host that can serve as a source of blood, which is sterile unless the animal is septic. Prior to imbibing a meal, tsetse probe their host’s skin in an effort to locate an effectual bite site, and during this process the fly’s mouthparts likely come into direct contact with a diverse assemblage of bacteria that reside in this environment. Different tsetse species exhibit distinct host preferences [41], and this results in exposure to vertebrate host-specific microbiotas. Presumably all or a proportion of these bacteria represent the population that colonizes tsetse’s gut. Additionally, adult tsetse feed multiple times, so the diversity of environmentally acquired bacteria that resides in a fly’s gut likely increases as a function of age (which is a parameter that we did not control for in this study). These and other ecological variables (e.g., temperature, humidity, temporal availability of blood, etc.) cumulatively account for the variability in the taxonomic structure and density of bacterial communities we observed in G. pallidipes captured at geographically isolated locations. Further experimental studies are required to decipher the dynamic mechanisms that underlie colonization of tsetse’s gut by bacteria that reside in the fly’s environment.

To date, no experimental evidence exists to suggest that environmentally acquired bacteria mediate trypanosome infection outcomes in tsetse. However, studies performed using other insect vector model systems indicate bacteria of this nature do modulate host vector competence. For example, Anopheles gambiae, which is the principle vector of human malaria (Plasmodium sp.), harbors a taxonomically diverse assemblage of gut-associated bacteria [42]. Among this population, a commensal from the genus Enterobacter (designated ‘Enterobacter sp. Z, or Esp_Z) exhibits direct anti-Plasmodium activity via the production of toxic reactive oxygen intermediates [43]. Plasmodium-susceptible laboratory lines of A. gambiae were rendered highly resistant to parasite infection when they had been inoculated with Esp-Z prior to exposure to an infectious blood meal [43]. Additionally, A. gambiae can harbor Serratia marcescens in its gut, and this bacterium is also associated (through a currently unknown mechanism) with a Plasmodium-refractory host phenotype [44, 45]. Both Enterobacter and Serratia strains were identified within the gut of field-captured tsetse (this study, and [31]). Additionally, Serratia was found to reside at low densities within the gut of colonized flies. The functional relationship between these bacteria (as well as other environmentally-acquired commensals) and tsetse’s competence as a vector of African trypanosomes remains to be elucidated.

Tsetse’s well-studied maternally-transmitted symbionts mediate host vector competence through indirect mechanisms. This study, along with previous ones [26, 46], suggest that tsetse populations that harbor Sodalis are more likely to be infected with trypanosomes than are flies that do not harbor this bacterium, or harbor the bacterium at a relatively low density [7]. Although the mechanism that underlies this phenomenon is currently not well understood, it may involve the inhibition of tsetse-derived trypanocidal lectins by N-acetyl glucosamine, the latter of which is produced when chitin is degraded by Sodalis secreted chitinase [24]. A more recent theory suggests that a Sodalis-hosted prophage induces the production of potent antimicrobial effector molecules in trypanosome challenged flies [47]. Tsetse’s obligate endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia, also indirectly modulates trypanosome infection outcomes in tsetse. More specifically, peptidoglycan (PGN), which is shed by Wigglesworthia as the bacteria multiplies, induces bacteriocytes to produce PGRP-LB. PGRP-LB presents catalase activity that degrades free PGN, which would otherwise induce tsetse immune pathways that damage Wigglesworthia. Interestingly, PGRP-LB also exhibits anti-trypanosomal activity and acts as a first line in defense against parasite infections in the gut [34]. The quantity of this protein is proportional to Wigglesworthia density [48], and flies that harbor more of this bacterium likely exhibit greater resistance to parasites. In addition, flies that undergo intrauterine larval development in the absence of Wigglesworthia exhibit higher susceptibility to trypanosomes as adults [12, 20]. An important difference between wild-type and Wigglesworthia-free adults relates to the integrity of their peritrophic matrix (PM). Wigglesworthia-free adults fail to produce a structurally robust PM, which is a sleeve-like barrier that lines the fly midgut and separates immuno-reactive epithelial cells from the parasite-containing blood bolus. As such, the midgut of PM compromised flies respond immunologically to the presence of parasites earlier in the infection process than in wild-type individuals that house an intact PM. This irregular immune response exhibits limited trypanocidal activity, thus resulting in the parasite-susceptible phenotype exhibited by these flies [20]. In addition, Wigglesworthia-free flies present a compromised cellular immune system and lack a functional melanization cascade [19]. Whether this immune pathway influences trypanosome infection establishment in tsetse’s gut remains to be determined.

Conclusions

In conclusion, findings from this study enhance our understanding of the relationship between the environment in which distinct tsetse populations reside, the structure of enteric bacterial communities and factors that mediate the establishment of trypanosome infections. Additionally, bacteria cultured during this study will contribute to our repertoire of culturable insect gut bacteria that may potentially find application in microbe-driven modulation of vector competence in tsetse and related flies. These findings can find application in the design of tsetse vector control strategies using paratransgenic microbes to halt the transmission of trypanosomes within the tsetse fly. Future studies will aim at further investigating the relationship between host vector competence and the presence of environmentally acquired microbes.

Methods

Fly collections

Flies were trapped from May 2013 to August 2013 in Shimba Hills National Reserve, Kenya (4°15′21.99″S, 39°23′46.13″E), the Trans Mara, Kenya (1°16′59.89″S, 34°55′49.27″E), Western Kenya (on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria; 0°36′54.11″S, 34°05′25.15″E), Nguruman escarpment, Kenya (1°45′53.33″S, 36°01′02.55″E) and Murchison Falls, Uganda (2°16′13.5″E, 31°41′09.15″E). Tsetse were captured using Epsilon F3 Ngu cloth traps and biconical cloth traps baited with acetone and phenol, which are established tsetse olfactory attractants [25, 26]. Glossina were identified to species based on morphological criteria.

Depending on their intended experimental use (see details below), captured tsetse flies were either dissected in the field (and trypanosome infections status scored by microscopy analysis) or stored in ethanol (either whole flies or dissected midguts) for transport back to the lab at Yale University.

Culture dependent identification of bacteria from midguts of field-captured tsetse

Culture dependent isolation of bacterial samples from the tsetse midgut (G. pallidipes, G. brevipalpis, G. fuscipes, G. fuscipleuris) was conducted according to the method outlined by Lindh and Lehane [31]. Stringent procedures were employed so as to process all samples under sterile conditions. Specifically, flies were surface sterilized via submersion for 5 min in 10% bleach, 5 min in 70% ethanol, and 5 min in sterile water (solutions were replaced regularly). All tools and dissection surfaces were sterilized after each dissection using 100% ethanol. Fly midguts were microscopically extracted and homogenized in 20ul sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS) using a sterilize motorized pellet pestle. Homogenized midguts were serially diluted up to a 10− 10 dilution in sterile PBS, and a volume of each dilution was plated.

Bacteria were cultured in ambient and microaerophillic (using GasPak EZ Campy Container System; BD Bioscience) atmospheres and on three types of solid (agar-based) media: Brain-Heart Infusion supplemented with 10% blood (BHIB), Mitsuhashi-Mahamarosh (MM) or Luria-Bertani (LB). Sterile technique was confirmed by plating an aliquot of the PBS used for fly homogenization onto all three types of solid media followed by incubation in ambient or microaerophilic atmospheres.

Plates were examined daily for the presence of bacterial colonies, and those exhibiting a unique morphology were inoculated into 900ul of their respective media and grown overnight in a shaking incubator at 30 °C. Liquid cultures were preserved in 10% glycerol, flash frozen and stored at − 80 °C.

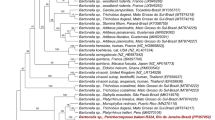

16S rDNA-based phylogenetic analysis of culturable bacteria

DNA was extracted from bacterial cells using a Qiagen DNAeasy blood and tissue kit. DNA isolated from bacterial clones was PCR amplified using primers (Additional file 1: Table S2) that specifically target the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. Bacterial clones (n = 38) were taxonomically characterized using this procedure. PCR products were sequenced at the DNA analysis facility on Science Hill at Yale University. The 16S rRNA sequence data was compared to catalogued sequences using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) and CLC Genomics Workbench v.6 (Venlo, Netherlands).

PCR amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and Illumina library preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from the guts of field-captured G. pallidipes (n = 112) using either a DNEasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or a Masterpure-Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (EpiCentre). Negative control extractions were performed on reagents from the Qiagen and Epicentre DNA extraction kits, as well as the New England Biolabs Phusion PCR kit (see below). Samples were then PCR amplified using barcoded Illumina fusion primers (generously donated by Dr. Howard Ochman) that specifically target a 300 bp region of the V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene [49]. Primers used to generate 16S rDNA products can be found at (ftp://ftp.metagenomics.anl.gov/data/misc/EMP/SupplementaryFile1_barcoded_primers_515F_806R.txt). Each sample was assigned a unique 12 base pair Golay barcode located on the 806R primer. Each PCR reaction was carried out in 30ul of volume containing 1ul of DNA, 0.2ul of Phusion Taq (New England Biolabs), 6ul of 5× reaction buffer, 0.6ul of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.75ul of 10uM forward and reverse primers and 20.7uls of dH20. Cycling conditions were 1 min of initial denaturation at 98 °C followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 54 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 15 s and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 2 min. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate, pooled together and analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. The final PCR product, which was 384 bp in length, included 5′ and 3’ Illumina barcodes that flanked the paired 300 bp target region.

A previous characterization tsetse’s gut microbiota revealed that the population is dominated (> 99% of the total population) by obligate Wigglesworthia [7]. This phenomenon significantly reduced, or may have entirely excluded, detection and accurate quantification of other less well represented microbes. In an effort to reduce Wigglesworthia bias and thus obtain a more in-depth representation of low density bacteria, we performed an EcoRV restriction endonuclease (New England BioLabs) digest of the pool of 16 s rDNA PCR fragments. This enzyme cuts within the V4 hypervariable region of Wigglesworthia’s 16S rRNA gene, but not this gene’s orthologue from Sodalis nor the majority of the environmental microbes identified previously [7]. Remaining PCR fragments were cleaned using Agencourt AMpure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. EcoRV digested DNA passed through the bead column and was thus excluded from downstream procedures. PCR products were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay (Life Technologies), and positive reactions were pooled at an equal molar concentration. In total, 16S rDNA sequences were pooled from 163 fly midguts. The pooled sample was sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq sequencing system at the Yale Center of Genome Analysis.

Next generation sequencing data analyses

Reads were quality checked using FastQC software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). The 16 s rRNA sequence dataset was demultiplexed and forward and reverse reads were paired using SeqPrep. In the event of a mismatched read, quality scores associated with each base were used to determine the appropriate pairing. In order to improve sequencing accuracy of low diversity samples, a phiX DNA control was added. To remove the phiX reads from the data set, paired reads were mapped to the phiX genome using Bowtie2 [50]. A list of reads not matching the phiX genome was generated using SamTools [51], and the resulting reads were separated from the phiX genome using QIIME software filter_fasta.py script [52]. Sequences were entered into the QIIME pipeline using the split_libraries_fastq.py command. Sequences were clustered via Uclust using the pick_otus.py command at 97% sequence similarity against the Greengenes Ribosomal database (http://greengenes.secondgenome.com/downloads). The reference file was customized to include the V4 region sequence from Wigglesworthia and Sodalis (these are absent from the Greengenes database). In order to remove possible chimeras and other PCR errors, all OTUs that did not align to the Greengenes database were excluded from the analysis. To remove OTUs with low read number, OTUs tables were filtered at 0.005% of the total number of reads [53]. The G. pallidipes samples were separately analyzed to determine the relationship between gut microbiota composition and tsetse trypanosome infection status, geographical location within one fly species. The relative abundance of each OTU was measured using the summarize_taxa.py script (http://qiime.org/scripts/summarize_taxa.html).

For α-diversity (species richness) calculations, datasets were rarefied to a depth of 15,001 sequences per sample. Alpha-diversity was calculated using the “observed species” metric with ten iterations at each sequencing depth. The number of OTUs at each sampling depth was averaged to make the rarefaction curves. To compare the α-diversity between G. pallidipes populations in different locations, a two-sample t-test with 1000 Monte Carlo permutations was used. Beta diversity (β-diversity) was calculated for comparisons between geographically distinct populations of G. pallidipes captured in geographically distinct locales. Jackknifed principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and the unweighted UniFrac distance metric was used to visualize the difference between microbial communities form each population using ten jackknife replicates. We used an analysis for similarities (ANOSIM) test for group comparison between uninfected and infected flies from the same location using either unweighted or weighted unifrac distance matrices (n = 99 permutations).

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR assays for symbiont quantification and trypanosome detection

Total DNA was extracted from ethanol preserved G. pallidipes midguts (n = 41) using the MasterPure Complete DNA Purification kit (Epicentre). Sterile water was used as a template during each batch of DNA extractions in an effort to detect bacterial contamination. Prepared DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific).

Real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using a CFX96 Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Sodalis specific fliC and Wigglesworthia specific thiC gene primers were used to quantify the relative abundance of these bacteria present within trypanosome infected and uninfected G. pallidipes. This was performed by comparing of experimental sample cycle threshold (Ct) values to those derived from symbiont gene-specific internal standard curves [40]. Wigglesworthia cells are polyploid [40], thus in our analysis we measured genome copy number normalized to tsetse host β-tubulin gene copy number. The same method was applied to quantify Sodalis. RT-qPCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 8 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 1 min, and 55 °C for 1 min; and a melt curve of 55 °C to 95 °C in increments of 0.5 °C for 30 s. PCR primers are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2. All PCR assays were carried out in duplicate, and replicates were averaged for each sample. Negative controls were included in all amplification reactions.

Abbreviations

- AAT:

-

Animal African trypanosomiasis

- ANOSIM:

-

Analysis for similarities

- BHIB:

-

Brain heart infusion with blood

- Ct :

-

Threshold cycle

- G. :

-

Glossina

- HAT:

-

Human African trypanosomiasis

- LB:

-

Luria-Bertani media

- MM:

-

Mitsuhashi-Mahamarosh media

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinate analysis

- PGRP-LB:

-

Peptidoglycan recognition protein LB

- PM:

-

Peritrophic matrix

- rDNA:

-

Ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- RT-qPCR:

-

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

References

Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Franco JR, Paone M, Diarra A, Ruiz-Postigo JA, Fèvre EM, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG. Estimating and mapping the population at risk of sleeping sickness. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1859.

Morrison LJ, Vezza L, Rowan T, Hope JC. Animal African trypanosomiasis: time to increase focus on clinically relevant parasite and host species. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:599–607.

Horn D. Antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2014;195:123–9.

Delespaux V, de Koning HP. Drugs and drug resistance in African trypanosomiasis. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10:30–50.

Aksoy S, Gibson WC, Lehane MJ. Interactions between tsetse and trypanosomes with implications for the control of trypanosomiasis. Adv Parasitol. 2003;53:1–83.

Wang J, Weiss BL, Aksoy S. Tsetse fly microbiota: form and function. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:69.

Aksoy E, Telleria EL, Echodu R, Wu Y, Okedi LM, Weiss BL, Aksoy S, Caccone A. Analysis of multiple tsetse fly populations in Uganda reveals limited diversity and species-specific gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4301–12.

Aksoy S. Wigglesworthia gen. nov. and Wigglesworthia glossinidia sp. nov., taxa consisting of the mycetocyte-associated, primary endosymbionts of tsetse flies. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:848–51.

Dale C, Maudlin I. Sodalis gen. nov. and Sodalis glossinidius sp. nov., a microaerophilic secondary endosymbiont of the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans morsitans. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:267–75.

Benoit JB, Attardo GM, Baumann AA, Michalkova V, Aksoy S. Adenotrophic viviparity in tsetse flies: potential for population control and as an insect model for lactation. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:351–71.

Chen X, Li S, Aksoy S. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:49–5.

Pais R, Lohs C, Wu Y, Wang J, Aksoy S. The obligate mutualist Wigglesworthia glossinidia influences reproduction, digestion, and immunity processes of its host, the tsetse fly. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5965–74.

Alam U, Medlock J, Brelsfoard C, Pais R, Lohs C, Balmand S, Carnogursky J, Heddi A, Takac P, Galvani A, Aksoy S. Wolbachia symbiont infections induce strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002415.

Akman L, Yamashita A, Watanabe H, Oshima K, Shiba T, Hattori M, Aksoy S. Genome sequence of the endocellular obligate symbiont of tsetse flies, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. Nat Genet. 2002;32:402–7.

Bing X, Attardo GM, Vigneron A, Aksoy E, Scolari F, Malacrida A, Weiss BL, Aksoy S. Unravelling the relationship between the tsetse fly and its obligate symbiont Wigglesworthia: transcriptomic and metabolomic landscapes reveal highly integrated physiological networks. Proc Biol Sci. 2017;284. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0360.

Michalkova V, Benoit JB, Weiss BL, Attardo GM, Aksoy S. Vitamin B6 generated by obligate symbionts is critical for maintaining proline homeostasis and fecundity in tsetse flies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5844–53.

Weiss BL, Wang J, Aksoy S. Tsetse immune system maturation requires the presence of obligate symbionts in larvae. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000619.

Weiss BL, Maltz M, Aksoy S. Obligate symbionts activate immune system development in the tsetse fly. J Immunol. 2011;188:3395–403.

Benoit JB, Vigneron A, Broderick NA, Wu Y, Sun JS, Carlson JR, Aksoy S, Weiss BL. Symbiont-induced odorant binding proteins mediate insect host hematopoiesis. elife. 2017;6:e19535.

Weiss BL, Wang J, Maltz MA, Wu Y, Aksoy S. Trypanosome infection establishment in the tsetse fly gut is influenced by microbiome-regulated host immune barriers. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003318.

Beard CB, O'Neill SL, Mason P, Mandelco L, Woese CR, Tesh RB, Richards FF, Aksoy S. Genetic transformation and phylogeny of bacterial symbionts from tsetse. Insect Mol Biol. 1993;1:123–31.

Aksoy S, Weiss B, Attardo G. Paratransgenesis applied for control of tsetse transmitted sleeping sickness. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;627:35–48.

Dale C, Welburn SC. The endosymbionts of tsetse flies: manipulating host-parasite interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:628–31.

Welburn SC, Maudlin I. Tsetse-trypanosome interactions: rites of passage. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:399–403.

Farikou O, Thevenon S, Njiokou F, Allal F, Cuny G, Geiger A. Genetic diversity and population structure of the secondary symbiont of tsetse flies, Sodalis glossinidius, in sleeping sickness foci in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1281.

Soumana IH, Simo G, Njiokou F, Tchicaya B, Abd-Alla AM, Cuny G, Geiger A. The bacterial flora of tsetse fly midgut and its effect on trypanosome transmission. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S89–93.

Geiger A, Ponton F, Simo G. Adult blood-feeding tsetse flies, trypanosomes, microbiota and the fluctuating environment in sub-Saharan Africa. ISME J. 2015;9:1496–507.

Weiss B, Aksoy S. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:514–22.

Geiger A, Fardeau ML, Grebaut P, Vatunga G, Josénando T, Herder S, Cuny G, Truc P, Ollivier B. First isolation of Enterobacter, Enterococcus, and Acinetobacter spp. as inhabitants of the tsetse fly (Glossina palpalis palpalis) midgut. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1364–70.

Geiger A, Fardeau ML, Njiokou F, Joseph M, Asonganyi T, Ollivier B, Cuny G. Bacterial diversity associated with populations of Glossina spp. from Cameroon and distribution within the campo sleeping sickness focus. Microb Ecol. 2011;62:632–43.

Lindh JM, Lehane MJ. The tsetse fly Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Diptera: Glossina) harbours a surprising diversity of bacteria other than symbionts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:711–20.

Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Clayton AM, Sandiford SL, Souza-Neto JA, Mulenga M, Dimopoulos G. Natural microbe-mediated refractoriness to Plasmodium infection in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2011a;332:855–8.

Narasimhan S, Fikrig E. Tick microbiome: the force within. Trends Parasitol. 2015;31:315–23.

Wang J, Wu Y, Yang G, Aksoy S. Interactions between mutualist Wigglesworthia and tsetse peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP-LB) influence trypanosome transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12133–8.

Medlock J, Atkins KE, Thomas DN, Aksoy S, Galvani AP. Evaluating paratransgenesis as a potential control strategy for african trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2374.

Van Den Abbeele J, Bourtzis K, Weiss B, Cordón-Rosales C, Miller W, Abd-Alla AM, Parker A. Enhancing tsetse fly refractoriness to trypanosome infection--a new IAEA coordinated research project. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S142–7.

Wang Y, Gilbreath TM, Kukutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24767.

Wong CN, Ng P, Douglas AE. Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1889–900.

Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:307–21.

Rio RV, Wu YN, Filardo G, Aksoy S. Dynamics of multiple symbiont density regulation during host development: tsetse fly and its microbial flora. Proc Biol Sci. 2006;273:805–14.

Clausen PH, Adeyemi I, Bauer B, Breloeer M, Salchow F, Staak C. Host preferences of tsetse (Diptera: Glossinidae) based on bloodmeal identifications. Med Vet Entomol. 1998;12:169–80.

Boissiere A, Tchioffo MT, Bachar D, Abate L, Marie A, Nsango SE, Shahbazkia HR, Awono-Ambene PH, Levashina EA, Christen R, Morlais I. Midgut microbiota of the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae and interactions with Plasmodium falciparum infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002742.

Cirimotich CM, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. Native microbiota shape insect vector competence for human pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2011b;10:307–10.

Bando H, Okado K, Guelbeogo WM, Badolo A, Aonuma H, Nelson B, Fukumoto S, Xuan X, Sagnon N, Kanuka H. Intra-specific diversity of Serratia marcescens in Anopheles mosquito midgut defines Plasmodium transmission capacity. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1641.

Bahia AC, Dong Y, Blumberg BJ, Mlambo G, Tripathi A, BenMarzouk-Hidalgo OJ, Chandra R, Dimopoulos G. Exploring Anopheles gut bacteria for Plasmodium blocking activity. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2980–94.

Farikou O, Njiokou F, Mbida Mbida JA, Njitchouang GR, Djeunga HN, Asonganyi T, Simarro PP, Cuny G, Geiger A. Tripartite interactions between tsetse flies, Sodalis glossinidius and trypanosomes--an epidemiological approach in two historical human African trypanosomiasis foci in Cameroon. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:115–21.

Hamidou Soumana I, Loriod B, Ravel S, Tchicaya B, Simo G, Rihet P, Geiger A. The transcriptional signatures of Sodalis glossinidius in the Glossina palpalis gambiensis flies negative for Trypanosoma brucei gambiense contrast with those of this symbiont in tsetse flies positive for the parasite: possible involvement of a Sodalis-hosted prophage in fly Trypanosoma refractoriness? Infect Genet Evol. 2014;24:41–56.

Wang J, Aksoy S. PGRP-LB is a maternally transmitted immune milk protein that influences symbiosis and parasitism in tsetse's offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10552–7.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–22.

Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 1000 genome project data processing subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–6.

Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, Mills DA, Caporaso JG. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:57–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ying Yang, Yineng Wu and Michelle O’Neill for technical assistance, and Dr. Norah Saarman for assistance with qGIS software. We are grateful to the International Atomic Energy Association (as part of the Coordinated Research Project) for facilitating publication of this data.

Funding

This study was supported by awards from NIAID UO1 AI115648, D43 TW007391, AI051584, AI068932. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or prepare the manuscript. BCG was generously funded by a Downs International Health Student Travel Fellowship, awarded by the Yale School of Public Health. The publication charge was funded by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as part of the Coordinated Research Project “Enhancing tsetse fly refractoriness to trypanosome infection.”

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and reagents/materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Microbiology Volume 18 Supplement 1, 2018: Enhancing Vector Refractoriness to Trypanosome Infection. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BCG, BLW, POM, FNW and JEA, and SA and RE, participated in tsetse fly collections in Kenya and Uganda, respectively. BCG and BLW performed in vitro cultivations, EA constructed 16S rDNA libraries and BCG, BLW and EA performed data management and analysis; BCG, BLW and SA conceived, designed and coordinated the study. BCG, BLW and SA wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Bacteria isolated from tsetse fly midguts using culture dependent techniques. Table S2. PCR primers used in this study. Figure S1. Average taxonomic composition and % abundance of environmentally acquired (top graph) and symbiotic bacteria (bottom graph) found in midguts of uninfected and trypanosome infected G. pallidipes collected in Nguruman, Kenya, Shimba Hills, Kenya and Murchison Falls, Uganda. (DOCX 508 kb)

Rights and permissions

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source is given.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffith, B.C., Weiss, B.L., Aksoy, E. et al. Analysis of the gut-specific microbiome from field-captured tsetse flies, and its potential relevance to host trypanosome vector competence. BMC Microbiol 18 (Suppl 1), 146 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-018-1284-7

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-018-1284-7