Abstract

Wolbachia is a genus of maternally inherited endosymbionts that can affect reproduction of their hosts and influence metabolic processes. The pollinator, Valisia javana, is common in the male syconium of the dioecious fig Ficus hirta. Based on a high-quality chromosome-level V. javana genome with PacBio long-read and Illumina short-read sequencing, we discovered a sizeable proportion of Wolbachia sequences and used these to assemble two novel Wolbachia strains belonging to supergroup A. We explored its phylogenetic relationship with described Wolbachia strains based on MLST sequences and the possibility of induction of CI (cytoplasmic incompatibility) in this strain by examining the presence of cif genes known to be responsible for CI in other insects. We also identified mobile genetic elements including prophages and insertion sequences, genes related to biotin synthesis and metabolism. A total of two prophages and 256 insertion sequences were found. The prophage WOjav1 is cryptic (structure incomplete) and WOjav2 is relatively intact. IS5 is the dominant transposon family. At least three pairs of type I cif genes with three copies were found which may cause strong CI although this needs experimental verification; we also considered possible nutritional effects of the Wolbachia by identifying genes related to biotin production, absorption and metabolism. This study provides a resource for further studies of Wolbachia-pollinator-host plant interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wolbachia is a genus of maternally inherited intracellular endosymbiotic bacteria belonging to the order Rickettsiales and is estimated to be distributed in ca. 44% of arthropods, and 66% of insects, and also shows mutualistic symbiosis in nematodes [1,2,3]. Wolbachia is classified as a single species, Wolbachia pipientis, divided into supergroups A to U, with supergroups A and B infecting arthropods exclusively, based on the phylogenetic analysis using the 16 S rRNA, wsp, gatB, coxA, hcpA, fbpA, and ftsZ markers [4,5,6,7]. Wolbachia is transmitted mainly via vertical transmission from mother to offspring with high fidelity, but also can be transmitted across different taxa by host shift, especially for supergroups A and B occurring between both phylogenetically close and more distant host species [4, 8, 9].

To increase transmission and propagation, Wolbachia can impact the reproductive system of arthropod and nematode species using diverse methods, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), feminization of genetic males, parthenogenesis, and male-killing [10,11,12,13]. CI is the most common reproductive manipulation effect induced by Wolbachia, and can be used as an important means to control arboviruses by release of CI including males [14] or CI driven replacement of uninfected mosquito populations [15, 16]. Co-expression of the prophage WO genes cifA and cifB in Wolbachia can cause a CI phenotype, which can be rescued by maternal cifA expression [17]. Phylogenetic analysis of the cif protein, which is encoded by the cif gene, shows that the evolution of cifA and cifB is related to each other. Both cifA and cifB can be divided into five distinct phylogenetic clades as type I-V [18,19,20].

Wolbachia can also exert an influence on numerous processes in the host, including immune, behavioral, and metabolic processes [21], which may be related to their occupation of host cells and reproductive tissues [22]. Wolbachia may be beneficial in insects by protecting them from pathogenic viral infection and increasing host fitness and fecundity [23,24,25,26], although there can also be fitness costs particularly in transgenic Wolbachia infections [27]. In nematodes and Cimex lectularius, Wolbachia functions as an obligatory mutualistic endosymbiont [20, 28] but there are also Wolbachia infections with few phenotypic effects on host [27].

The obligate mutualism of figs and fig-pollinating wasps has been one of the classic models used for testing theories of co-evolution and cospeciation due to the high species-specificity of these relationships [29]. Figs (Ficus, (Moraceae) include around 750 species worldwide, distributed in the tropics and subtropics [30, 31]. Figs and fig-pollinating wasps (Agaonidae; Chalcidoidea; Hymenoptera) are obligate mutualists that have coevolved for over ~ 75 million years [32, 33]. Except for pollinators, numerous non-pollinating fig wasps feed on fig tissue or other fig wasps [34,35,36] and some lay eggs outside the syconium with remarkable long ovipositors. In most fig species, each syconium contains 50–500 wasps of a few different species developing in close proximity [37]. As such, this is a useful system for investigating the impact of ecological interactions on Wolbachia transmission and persistence.

More than half of the pollinating fig wasp species from North America, Australia, Asia, and Africa are infected with Wolbachia [9, 37,38,39,40], which is high compared to many other insects [40]. The comparison of endosymbiont diversity between female and male syconium in the dioecious Ficus hirta using high-throughput sequencing and biological databases showed Wolbachia is dominant in the male syconium infested by fig wasps in contrast to the female syconium, because the latter has no galled flowers for fig wasp larvae [41]. Moreover, genomes of Wolbachia from three pollinating fig wasp species (Ceratosolen solmsi, Kradibia gibbosae, and Wiebesia pumilae) have been classified into supergroup A and only one cryptic (incomplete structure) WO prophage bearing CI related genes has so far been found, whereas Wolbachia with cryptic prophages usually come with least one intact WO prophage consisting of gene sequences of the head, baseplate, and tail modules, through which the prophage could form intact virions [42].

To recover the Wolbachia genome, we used a high-quality chromosome-level genome for V. javana Mayr (Agaonidae, Chalcidoidea, Hymenoptera), formerly known as Blastophaga javana Mayr, assembled using a combination of PacBio long-read sequencing and Illumina short read sequencing [43]. From the V. javana genomic data, we discovered a significant fraction of Wolbachia genome sequence and used these to assemble two novel Wolbachia strains. We explored their phylogenetic relationship with described Wolbachia strains based on MLST and explored the possibility that strains could induce CI by exploring the presence of genes responsible for CI. Furthermore, to explore the possibility of nutritional mutualism, we identified mobile genetic elements (MGEs) including prophages and insertion sequences, genes related to biotin (vitamin B7) synthesis and metabolism, and cif homologous genes in the mixed genome. This genome assembly will serve as a useful resource for further studies of Wolbachia-pollinator-host interactions, comparative genomics, and coevolution.

Results

V. javana double infection with two novel Wolbachia strains

Based on the length of the Wolbachia mixed genome of V. javana and the number of fragments, we selected the sequence with a length of 2,352,926 bp (2.24 Mb) as the final one (Table 1). After polishing using Illumina data, a genomic sequence with a length of 2,352,827 bp was obtained. The GC content of the genome was 35.0%, and the number of CDS (protein coding sequence) and RNAs were 2,825 and 62, respectively (Table 2). Since the genome size of the mixed genome is much larger than the known Wolbachia (Table S1) and the genomes are difficult to separate, MLST (multilocus sequence typing) sequences from the infected wMel strain Drosophila melanogaster (ST = 1), were used to search for five MLST housekeeping genes. There were at least two sets of MLST sequences with unique allelic profile combinations in the genomes (Table 3). However, none of these combinations belong to any known Wolbachia strains, so they are identified as two novel strains called wJav1 and wJav2.

Identification of w Jav1 and w Jav2

The MLST sequences in wJav1 and wJav2 can be divided into two possible groups (Table 4) and are unique when compared with the known MLST sequences in the pubMLST database. The wJav1 and wJav2 strains have different profiles of gatB and coxA (Fig. 1; Table 4). The Sole_A_17 − 02 and wJav2 strains only differ for the hcpA gene (Table 4), suggesting that the wJav strains are linked to this strain, perhaps due to horizontal transmission among hosts. The gatB and coxA sequences can be divided into two wJav types (Fig. 1). Based on hcpA and ftz sequences, V. javana Wolbachia are the most similar in the PubMLST to the white-backed planthopper Sogatella furcifera (Sfur_A_YN4) and Megastigmus sp.3 (Mspi_A_wspe) (Fig. 1, Table S2). The former is the main pest on rice paddies throughout Asia [44], and the latter is a serious pest of conifer species with four basic feeding types [45].

Phylogenetic analysis of MLST data for 21 species of Wolbachia belonging to different supergroups based on maximum-likelihood. SH-aLRT (SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test) and UFBoot (ultrafast bootstrap approximation) support values are given on nodes. The corresponding sample ids, hosts, strains, and colors represent different supergroups of Wolbachia strains can be found in Table S2. MLST groups can be found in Table S8

We randomly selected 21 Wolbachia MLST sequences (Table S2) belonging to different supergroups (A, B, D, F, H) and different hosts to construct an evolutionary tree by the maximum likelihood (ML) method. The ML tree showed that both wJav1 and wJav2 belong to supergroup A and are closely related to each other (Fig. 1). The most similar strain of wJav2 of group 1 is Sole_A_17 − 02 infecting the fire ant (Solenopsis, Apocrita, Hymenoptera) which belongs to supergroup A (Fig. 1, Table S2). The relationship between the mixed genomes and the remaining 165 Wolbachia genomes was further evaluated by average nucleotide identity (ANI) (Table S1). The mixed genomes having the highest ANI with most Wolbachia sequences belonging to supergroup A (Table 5). Combining the ANI result with the MLST ML tree (Fig. 1), we are confident that both wJav1 and wJav2 belong to supergroup A.

Mobile genetic elements in w Jav1 and w Jav2

MGEs, mainly including prophage and insertion sequence (IS) in bacteria, are an important conduit for bacteria to acquire foreign genes and contribute to genome recombination. In the mixed genomes of wJav1 and wJav2, a total of two prophages (Fig. 2B) and 256 insertion sequences (Fig. 2A) were found, including 201 confirmed and 55 putative ISs.

Summary of the mobile genetic elements situation in the mixed genomes of wJav1 and wJav2. (A) Proportion of ten main types of insertion sequence families. (B) Regions of two prophages referred to as WOjav1-2 in the genome (see Fig. 3 and Table S3 for details). The integrity of the prophage regions is marked by a different color

Two prophages were as assigned the names WOjav1 and WOjav2, and most of the regions in them (Fig. 2B) are phage-like proteins, hypothetical proteins, and transposase proteins (Fig. 3; Table S3). WOjav1 is cryptic (structure incomplete) and only contains transposase proteins and minor tail proteins. However, WOjav2 is relatively intact, with complete phage replication and assembly related genes such as transposases, head morphogenesis proteins, baseplate assembly proteins with lysozyme, and tail proteins (Table S3).

Prophage regions were detected in the mixed genomes of wJav1 and wJav2 using the PHASTER server. The number of genes discovered in each prophage region is shown in the lower panel with different colors. See Table S3 for details

The main types of ISs are similar to supergroup A Wolbachia, in that they are from the IS5, IS4, IS630, and IS110 families, which account for 38.28% (98), 19.92% (51), 16.8% (43), and 12.5% (32) of ISs, respectively. In the dominant IS family, there are two subgroups of IS5 named IS5_ssgr_IS903 (n = 43) and IS5_ssgr_IS1031 (n = 21) in 201 confirmed ISs. The IS families of the Wolbachia of V. javana from F. hirta are similar to the endosymbiont of the fig wasp Ceratosolen solmsi from Ficus hispida but numbers differ, 201 ISs for V. javana and 86 for C. solmsi [46].

Cif genes in w Jav1 and w Jav2

In total, 4 proteins encoding genes were found to be aligned with two types (I and IV) of CifA, and 57 were aligned with three types (I, II, and V) of CifB in the wJav1 and wJav2 genomes (Table S4). The queried sequences fig|953.597.peg. 1691 (335 bp) and fig | 953.597.peg 1692 (1112 bp) may be the same cifA gene, but they are annotated as two genes because of multiple stop codons (Table S4). Therefore, the two genes were treated in tandem as one gene in the subsequent phylogenetic analysis. Fig | 953.597.peg 384 (1478 bp) and fig | 953.597.peg 1839 (1511 bp) are cifA genes (Table S4). The alignment length between fig|953.597.peg.995 and type V cifB is too short, and the alignment position is 3703aa − 3939aa (Table S4). Since this part is an ANK protein domain and is not a key conserved region of CifB, it was not analyzed further. Therefore, at least three different pairs of cif genes (wJav_pair1-3 for short) were identified in the wJav1 and wJav2 genomes (Table S4). An ML tree involving wJav_pair1-3 and other different types of cif genes (Table S5, Table S6 [20]) indicated that all wJav_pair1-3 belong to type I, and wJav_pair1-2 were particularly close and may be diverged from the same gene (Fig. 4).

ML trees of (A) cifA and (B) cifB genes pairs in wJav1-2 genomes and 19 Wolbachia strains. The SH-aLRT and UFBoot support values are given at the nodes. Supergroups of the Wolbachia strains are given in parentheses. * refers to CI (cytoplasmic incompatibility) host phenotype. ** refers to CI and MK (male killing). Corresponding colors that represent different cif types could be referred to Table S5. The corresponding strain names can be found in Table S6

Genes related to biotin synthesis and metabolism in w Jav1 and w Jav2

Based on the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, the wJav1 and wJav2 mixed genomes do not contain any key genes (BioF/A/D/B) for biotin synthesis. However, the genes of glutaryl-[acp] methyl ester and pimeloyl-[acyl carrier protein] methyl ester, fabF/G/Z/I, which are the key precursors for the synthesis of biotin, and the genes birA, which metabolize biotinyl-5 ‘- AMP and holo-[carboxylase] downstream, are present (Fig. 5). The genome-wide functional annotation based on the RAST and eggnog web servers also indicated that the mixed genomes do not contain any key genes for the synthesis of biotin; however, the gene bioY for uptake of biotin from the host, and the gene birA that uses biotin as an essential precursor to synthesize their metabolites were present (Table 6).

Schematic illustration of genes related to biotin synthesis and metabolism in wJav1-2. The numbers in the box indicate the Enzyme Commission number. White and green boxes indicate the absence and presence of the corresponding enzyme, respectively, based on RAST annotations. See Table 6 for details

Discussion

The high proportion of Wolbachia sequences in the PacBio data set for V. javana is indicative of a high Wolbachia titer. In contrast, Wolbachia can fail to proliferate in some wasp hosts. For example, as a maternal effect gene, Wolbachia identity suppressor (Wds) controls the titer of Wolbachia in Nasonia body and inhibits adverse effects from Wolbachia due to endosymbiont overproliferation [47]. Perhaps the high titer of Wolbachia in V. javana reflects a recent symbiotic relationship where control of the endosymbiont has not yet evolved, although there may also be a direct impact of diet composition of the pollinator that affects Wolbachia titers [48].

Two strains of Wolbachia from supergroup A appear to infect V. javana (Fig. 1, Table S1, Table S2). Other studies have shown that fig wasps could be infected by multiple strains of Wolbachia, and the strains of infected pollinators are mainly from supergroup A [9, 49]. Three possible scenarios may lead to the production of double infections: (i) Wolbachia are introduced into the same host multiple times, (ii) Wolbachia have diverged after invasion among lineages and are then transferred horizontally between lineages, and (iii) the common ancestor of V. javana was multiply infected, and this situation persisted during further divergence [50]. A double infection in a host may be maintained by synergism among different Wolbachia strains, but also through patterns of incompatibility produced through reproductive effects [51]. The presence of multiple strains can lead to a gene exchange between bacterial strains [52], and the strains can differ in density in a host [53].

The presence of multiple pairs of type I cif genes with three copies suggests that wJav1 and wJav2 are likely to induce strong CI. The MLST analysis indicates that related species of V. javana infected with Wolbachia are known to cause CI (Fig. 1). The closest endosymbiont in the cif gene ML tree was from Dactylopius coccus which has a type I cif (Fig. 3, Table S6) that leads to CI [54]. The cif genes belonging to type I generally cause and rescue CI (as shown in transgenic Drosophila and Culex pipiens [55] [56]). Wolbachia CI strength is related to cifA/cifB homolog similarity and copy number [18]. A strain with two or three copies such as wRi and wHa in Drosophila simulans induces strong CI [18]. Experiments are needed to test the prediction that strong CI is present in V. javana.

Ficus hirta is a dioecious plant, with far more female trees in the field than male trees [57]. The wingless male pollinator V. javana spend their whole life cycle in the figs of male trees (gall figs). The female wasps will fly out of gall figs after mating to spread Wolbachia and lay eggs in the gall flowers of other trees [58,59,60,61]. Female therefore spread Wolbachia through maternal transmission and the rate of spread will be enhanced by CI. When Wolbachia-uninfected females of V. javana lay eggs inside gall figs where Wolbachia-infected male pollinators are present, the offspring of the Wolbachia-uninfected females of V. javana will have a higher proportion of hatched males or eggs will fail to hatch. Studies have shown that both male and female pollinators of fig wasps can mate multiple times, although many females mate only once. In Ceratoolen solmsi marchali, females that multiply mate produce more female offspring, while the number of male offspring does not change significantly, resulting in a higher female sex ratio in offspring [62]. Combining this phenomenon with the reproductive regulation induced by Wolbachia, we speculate that after mating once, uninfected females will produce a male biased set of offspring (the oosperm dies, and the male figs wasps develops from the unfertilized egg). After multiple mating, the probability of females and male fig wasps uninfected by Wolbachia is high, resulting in an increase in the survival of females (oosperm). In addition, the high frequency of Wolbachia in populations may contribute to gender imbalance (female-biased sex ratios) of fig wasps [63]. However, experiments on infected and uninfected lines are required to test this further.

While Wolbachia from V. javana appears to have lost biotin-related genes, Wolbachia could still help the pollinators to absorb and metabolize biotin, which is synthesized by the host plant. As an essential vitamin for insects [64], biotin functions as a covalently-bound cofactor in various carboxylases, which have major roles in fatty acid biosynthesis, amino acid, and fatty acid catabolism, and also function in the citric acid cycle [65, 66].

To determine the distribution of biotin-related genes in the Wolbachia-pollinator-host plant system, we compared genome or transcriptome data from different fig tissues at the receptive phase (ostiolar bracts [67], female flowers [68], male flowers: unpublished), from the pollinator V. javana and from its endosymbiont Wolbachia. We found that biotin-synthesis genes in F. hirta, and the bract of the fig were more expressed (Table S7). The bracts, which are designed to attract insects, have additional biotin-related gene expression compared to female and male flowers of the male fig tree (Table S7). Female flowers, which are designed for pollination or oviposition, show the expression of bioA, pdhC, and sucB genes compared to male flowers (Table S7). Interestingly, V. javana has several biotin-related genes for absorbing and metabolizing biotin but far less than the endosymbiont (Table S7). Considering endosymbiont genes can be found in the host genome, a process of horizontal transfer from Wolbachia to the pollinator may have taken place [69]. Pollinators lay their eggs in the gall flowers, and their larvae feed on flowers with the biotin synthesis genes. Therefore, we speculate that pollinators acquire biotin from the gall flowers of F. hirta, and that Wolbachia helps the wasps to absorb and metabolize biotin.

Due to food with unbalanced nutrition and/or the absence of vitamin B, Wolbachia of Bemisia tabaci [70], planthoppers [71], and blood feeders maintain the function of synthesizing biotin. However, the Wolbachia of V. javana may have lost its biotin gene and F. hirta may provide a sufficiently balanced diet without the help of endosymbionts, or else Wolbachia may interact with different microorganisms (such as Cardinium [71]) which have a complete biotin synthesis pathway. Further studies including ecological observations, experimental studies, and molecular assessments are required to examine this further.

Conclusions

We have assembled the mixed Wolbachia genomes wJav1 and wJav2 of V. javana constituting two novel Wolbachia strains belonging to supergroup A. The MLST analysis helped to understand the relatedness of these Wolbachia to others. The annotation and analysis of prophages and insertion sequences shows some features that are different from other fig wasp endosymbionts, and highlights potential effects on genome evolution and the gene content of intracellular symbiosis, and these elements could be reused as gene manipulation tools. The discovery of at least three pairs of cifA-cifB genes from prophages belonging to type I suggests CI in the pollinators of F. hirta, and provides a basis for further studies on reproductive effects. The Wolbachia genome may help to provide a further understanding of nutritional aspects in this system.

Methods

Genomes assembly of Wolbachia

We collected nearly 500–1,000 female adult samples of V. javana from several figs of F. hirta in a single tree on Baiyun Mountain in Guangdong Province, China. The Wolbachia genomes were assembled based on whole genome sequencing data (CNCB accession number of GWHBDGE00000000 for V. javana).

165 assembled versions of Wolbachia genomes from different host species downloaded by NCBI were used as the reference genome (Table S1). The PacBio raw data of the V. javana genome (coverage 40 ×; 11.9 GB) were aligned to the Wolbachia reference genome (Table S1) using BLASR v5.3.5 [72]. Illumina sequencing reads of Wolbachia were acquired by aligning the Illumina genome sequences of V. javana with the Wolbachia reference genomes using kneaddata v0.10.0 (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/kneaddata). Then Wolbachia PacBio sequencing reads in V. javana were assembled using Flye assembler v2.9-b1768 [73], and the resulting assembly polished in Pilon version 1.23 [74] with Illumina data.

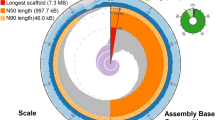

The large number of Wolbachia genomic fragments in the sequence data of V. javana [43] was found. There were 861,951 reads, with a total length of 12,005.70 Mb and a coverage of about 40× to the V. javana genome (296.34 Mb). After using BLASR to set different identities and maxscore, different numbers of Wolbachia reads were obtained (Fig. 6A and B). We performed genome assembly using reads under different parameters, and the results showed that many sequences did not belong to Wolbachia, falling between the parameters maxscore − 250 and − 300 of the BLASR screen (Table 1). Using the BLASR parameters as Identity ≥ 60% and maxscore ≤ -250, the aligned reads were assembled, and the final genome size exceeded 50 Mb, which was inconsistent with the normal size of the Wolbachia genome (Table S1). Therefore, we finally used the BLASR parameters Identity ≥ 60% and maxscore ≤ -300 to assemble the PacBio sequencing data of about 610 Mb. According to the assembled Wolbachia longest genome of 2,352,936 bp, the coverage is more than 270×.

Genome annotation

The genome size and GC content of the assembled Wolbachia were calculated with seqkit v0.9.2 [75]. Rapid genome annotation was conducted by RAST server (https://rast.nmpdr.org/rast.cgi). SEED Viewer v2.0 was used to view the KEGG pathway [76] through genomic results annotated by the RAST server. Insert sequences (ISs) were found in the IS database using ISsaga web server (http://issaga.biotoul.fr/issaga_index.php) [77]. The prophage regions in Wolbachia genome were annotated using Phaster web server (http://phaster.ca), and the visualization of the positions of the prophage regions was automatically generated by the Phaster web server. Functions and potentially involved pathways of the coding genes in Wolbachia genome were further annotated using eggnog Mapper web server (http://eggnog-mapper.embl.de) [78] and the KEGG automatic annotation server KAAS (https://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/) [79].

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Wolbachia in V. javana

To identify the Wolbachia strains in V. javana, five multilocus sequence typing genes (MLST) including gatB, fbpA, coxA, hcpA, and ftsZ in genomic data were blasted by BLASTN v2.9.0 according to the reference wMel strain of Drosophila melanogaster whose sequence type is typical ST1 (Table S2). The sequence type of the Wolbachia in V. javana was identified by aligning with PubMLST Wolbachia MLST database (http://www.pubmlst.org/Wolbachia/). In addition, ST sequences (sequences synthesized by housekeeping genes) of MLST in other Wolbachia genomes of A, B, D, F, and H supergroups were downloaded from PubMLST Wolbachia MLST database (Table S2).

Multiple sequence alignments for these MLST genes were aligned by MAFFT v7.310 [80]. The most suitable substitution model was calculated by ModelFinder [81], and the maximum-likelihood tree was constructed by IQ-tree v1.6.10 [82] with GTR + F + I + G4 model chosen according to BIC, and SH-aLRT test and ultrafast bootstrap with 1000 replicates. MLST genes of Wolbachia strain Zang_H of dampwood termites Zootermopsis angusticollis is selected as the outgroup (Table S2). In addition, the average nucleotide similarity (ANI) between Wolbachia genomes was calculated using fastANI v1.33 to further quantify the relationship between this genome and other Wolbachia genomes (Table S1) [83].

Identification of cif genes

Based on the typical CifA and CifB protein sequences of type I-V (Table S5), the cif genes and their homologous in Wolbachia of V. javana were blasted by blastp v2.9.0. The selection of homologues was based on Lindsey’s method [19] and slightly improved by the following criteria: (1) e ≤ 10− 30; (2) a percentage of identity matches ≥ 50%. The obtained cif genes were used to construct the ML tree with the cif genes from other Wolbachia strains [20]. Model (TPM3 + F + G4) and Bootstraps (SH-aLRT test and ultrafast bootstrap with 1000 replicates) settings are the same for cifA and cifB. Cif genes of wTri-2_pair1, wDacB_pair2, and wStri_pair1 were selected as outgroups (Table S6).

Data Availability

Data for this study will be completed after the manuscript is accepted for publication. All genome sequence data of Wolbachia are available in GWH database of the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) with accession no. GWHCBHN00000000. The raw genome sequencing data of Illumina and PacBio have been deposited in the GSA database of the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) with accession number of CRA010785. All result data were deposited in Figshare (doi: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23553021).

References

Werren JH. Biology of Wolbachia. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:587–609.

Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?–a statistical analysis of current data. Fems Microbiol Lett. 2008;281(2):215–20.

Zug R, Hammerstein P. Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS One. 2012;7(6).

Gomes TMFF, Wallau GL, Loreto ELS. Multiple long-range host shifts of major Wolbachia supergroups infecting arthropods. Sci Rep-Uk. 2022;12(1).

Laidoudi Y, Levasseur A, Medkour H, Maaloum M, Ben Khedher M, Sambou M, et al. An earliest endosymbiont, Wolbachia massiliensis sp. nov., strain PL13 from the bed bug (Cimex hemipterus), type strain of a new supergroup T. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21).

Olanratmanee P, Baimai V, Ahantarig A, Trinachartvanit W. Novel supergroup U Wolbachia in bat mites of Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2021;52(1):48–55.

Baldo L, Hotopp JCD, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microb. 2006;72(11):7098–110.

Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Burke GR, Moran NA. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:247–66.

Shoemaker DD, Machado CA, Molbo D, Werren JH, Windsor DM, Herre EA. The distribution of Wolbachia in fig wasps: correlations with host phylogeny, ecology and population structure. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2002;269(1506):2257–67.

Hurst GDD, Hammarton TC, Bandi C, Majerus TMO, Bertrand D, Majerus MEN. The diversity of inherited parasites of insects: the male-killing agent of the ladybird beetle Coleomegilla maculata is a member of the flavobacteria. Genet Res. 1997;70(1):1–6.

O’Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert A, Karr TL, Robertson H. 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89(7):2699–702.

Rousset F, Bouchon D, Pintureau B, Juchault P, Solignac M. Wolbachia endosymbionts responsible for various alterations of sexuality in arthropods. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 1992;250(1328):91–8.

Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(10):741–51.

Zheng X, Zhang D, Li Y, Yang C, Wu Y, Liang X, Liang Y, Pan X, Hu L, Sun Q. Incompatible and sterile insect techniques combined eliminate mosquitoes. Nature. 2019;572(7767):56–61.

Hoffmann AA, Montgomery B, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson P, Muzzi F, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476(7361):454–7.

Flores HA, de Bruyne JT, O’Donnell TB, Nhu VT, Giang NT, Trang HTX, et al. Multiple Wolbachia strains provide comparative levels of protection against dengue virus Infection in Aedes aegypti. Plos Pathog. 2020;16(4).

Shropshire JD, On J, Layton EM, Zhou H, Bordenstein SR. One prophage WO gene rescues cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(19):4987–91.

LePage DP, Metcalf JA, Bordenstein SR, On JM, Perlmutter JI, Shropshire JD, et al. Prophage WO genes recapitulate and enhance Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature. 2017;543(7644):243–7.

Lindsey ARI, Rice DW, Bordenstein SR, Brooks AW, Bordenstein SR, Newton ILG. Evolutionary genetics of cytoplasmic incompatibility genes cifA and cifB in prophage WO of Wolbachia. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10(2):434–51.

Martinez J, Klasson L, Welch JJ, Jiggins FM. Life and death of selfish genes: comparative genomics reveals the dynamic evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibility. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(1):2–15.

Landmann F. The Wolbachia endosymbionts. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(2).

Duron O, Gottlieb Y. Convergence of nutritional symbioses in obligate blood feeders. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36(10):816–25.

Guo Y, Hoffmann AA, Xu XQ, Zhang X, Huang HJ, Ju JF, et al. Wolbachia-induced apoptosis associated with increased fecundity in Laodelphax striatellus (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Insect Mol Biol. 2018;27(6):796–807.

Moriyama M, Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. Riboflavin provisioning underlies Wolbachia’s fitness contribution to its insect host. mBio. 2015;6(6).

Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Moriyama M, Oshima K, Hattori M, Fukatsu T. Evolutionary origin of insect-Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(28):10257–62.

Zug R, Hammerstein P. Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biol Rev. 2015;90(1):89–111.

Ross PA, Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. Evolutionary ecology of Wolbachia releases for disease control. Annu Rev Genet. 2019;53:93–116.

Comandatore F, Sassera D, Montagna M, Kumar S, Koutsovoulos G, Thomas G, et al. Phylogenomics and analysis of shared genes suggest a single transition to mutualism in Wolbachia of nematodes. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5(9):1668–74.

Janzen DH. How many parents do the wasps from a fig have? Biotropica 1979:127–9.

Ronsted N, Weiblen GD, Clement WL, Zerega NJC, Savolainen V. Reconstructing the phylogeny of figs (Ficus, Moraceae) to reveal the history of the fig pollination mutualism. Symbiosis. 2008;45(1–3):45–55.

Ronsted N, Weiblen GD, Savolainen V, Cook JM. Phylogeny, biogeography, and ecology of Ficus section Malvanthera (Moraceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;48(1):12–22.

Cruaud A, Ronsted N, Chantarasuwan B, Chou LS, Clement WL, Couloux A, et al. An extreme case of plant-insect codiversification: figs and fig-pollinating wasps. Syst Biol. 2012;61(6):1029–47.

Machado CA, Jousselin E, Kjellberg F, Compton SG, Herre EA. Phylogenetic relationships, historical biogeography and character evolution of fig-pollinating wasps. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2001;268(1468):685–94.

Rasplus J-Y, Kerdelhué C, Le Clainche I, Mondor G. Molecular phylogeny of fig wasps Agaonidae are not monophyletic. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences-Series III-Sciences de la Vie 1998, 321(6):517–527.

Campbell B, Heraty J, Rasplus J, Chan K, Steffen-Campbell J, Babcock C. Molecular systematics of the Chalcidoidea using 28S-D2 rDNA. Hymenoptera evolution, biodiversity and biological control CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia 2000:59–73.

Heraty JM, Burks RA, Cruaud A, Gibson GA, Liljeblad J, Munro J, et al. A phylogenetic analysis of the megadiverse Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). Cladistics. 2013;29(5):466–542.

Haine ER, Cook JM. Convergent incidences of Wolbachia infection in fig wasp communities from two continents. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2005;272(1561):421–9.

Chen LL, Cook JM, Xiao H, Hu HY, Niu LM, Huang DW. High incidences and similar patterns of Wolbachia infection in fig wasp communities from three different continents. Insect Sci. 2010;17(2):101–11.

Ahmed MZ, Greyvenstein OFC, Erasmus C, Welch JJ, Greeff JM. Consistently high incidence of Wolbachia in global fig wasp communities. Ecol Entomol. 2013;38(2):147–54.

Wang NX, Jia SS, Xu H, Liu Y, Huang DW. Multiple horizontal transfers of bacteriophage WO and host Wolbachia in fig wasps in a closed community. Front Microbiol. 2016;7.

Liu YF, Fan SL, Yu H. Analysis of Ficus Hirta fig endosymbionts diversity and species composition. Diversity. 2021;13(12).

Miao YH, Xiao JH, Huang DW. Distribution and evolution of the bacteriophage WO and its antagonism with Wolbachia. Front Microbiol. 2020;11.

Chen LF, Feng C, Wang R, Nong XJ, Deng XX, Chen XY, et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the pollinating fig wasp Valisia Javana. DNA Res. 2022;29(3).

Zhou C, Yang H, Wang Z, Long GY, Jin DC. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Sogatella furcifera (Horvath) exposed to different insecticides. Sci Rep-Uk. 2018;8.

Roques A, Skrzypczynska M. Seed-infesting chalcids of the genus Megastigmus Dalman, 1820 (Hymenoptera: Torymidae) native and introduced to the West Palearctic region: taxonomy, host specificity and distribution. J Nat Hist. 2003;37(2):127–238.

Neupane S, Bonilla SI, Manalo AM, Pelz-Stelinski KS. Complete de novo assembly of Wolbachia endosymbiont of Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae) using long-read genome sequencing. Sci Rep-Uk. 2022;12(1):125.

Funkhouser-Jones LJ, van Opstal EJ, Sharma A, Bordenstein SR. The maternal effect gene wds controls Wolbachia titer in Nasonia. Curr Biol. 2018;28(11):1692–1702.e6.

Lopez-Madrigal S, Duarte EH. Titer regulation in arthropod-Wolbachia symbioses. Fems Microbiol Lett. 2019;366(23).

Haine E, Cook J. Convergent incidences of Wolbachia infection in fig wasp communities from two continents. Proc Biol Sci Royal Soc. 2005;272:421–9.

Zhang YK, Zhang KJ, Sun JT, Yang XM, Ge C, Hong XY. Diversity of Wolbachia in natural populations of spider mites (Genus Tetranychus): evidence for complex infection history and disequilibrium distribution. Microb Ecol. 2013;65(3):731–9.

AA H. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Influential Passengers Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction 1997:42–80.

Werren JH, Zhang W, Guo LR. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia - reproductive parasites of arthropods. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 1995;261(1360):55–63.

Jeffries CL, Cansado-Utrilla C, Beavogui AH, Stica C, Lama EK, Kristan M, et al. Evidence for natural hybridization and novel Wolbachia strain superinfections in the Anopheles gambiae complex from Guinea. Roy Soc Open Sci. 2021;8(4).

Ramirez-Puebla ST, Ormeno-Orrillo E, de Leon AVP, Lozano L, Sanchez-Flores A, Rosenblueth M, et al. Genomes of candidatus Wolbachia bourtzisii wDacA and candidatus Wolbachia pipientis wDacB from the cochineal insect Dactylopius coccus (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae). G3-Genes Genom Genet. 2016;6(10):3343–9.

Shropshire JD, Bordenstein SR. Two-By-One model of cytoplasmic incompatibility: synthetic recapitulation by transgenic expression of cifA and cifB in Drosophila. Plos Genet. 2019;15(6).

Shropshire JD. Identifying and characterizing phage genes involved in Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. 2020.

Hui Y, Nanxian Z, Xiaocheng J, Yizhu C, Wenquan Z. Reproductive characters of Ficus Hirta Vahl (Moraceae) and its symbiotic fig wasps. Chin Bull Bot. 2004;21(6):682–8.

Weiblen GD. How to be a fig wasp. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:299–330.

Yu H, Zhao NX, Chen YZ, Herre EA. Male and female reproductive success in the dioecious fig, Ficus Hirta Vahl. In Guangdong Province, China: implications for the relative stability of dioecy and monoecy. Symbiosis. 2008;45(1–3):121–7.

Greeff JM, van Noort S, Rasplus JY, Kjellberg F. Dispersal and fighting in male pollinating fig wasps. Cr Biol. 2003;326(1):121–30.

Yu H, Nong XJ, Fan SL, Bhanumas C, Deng XX, Wang R, Chen XY, Compton SG. Olfactory and gustatory receptor genes in fig wasps: evolutionary insights from comparative studies. Gene 2023, 850.

Peng YQ, Zhang Y, Compton SG, Yang DR. Fig wasps from the centre of figs have more chances to mate, more offspring and more female-biased offspring sex ratios. Anim Behav. 2014;98:19–25.

Greeff JM, Kjellberg F. Pollinating fig wasps’ simple solutions to complex sex ratio problems: a review. Front Zool 2022, 19(1).

Dadd R. Nutrition: organisms. Comprehensive insect physiology, biochemistry and pharmacology 1985, 4:313–390.

Wood HG, Barden RE. Biotin enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46(1):385–413.

Knowles JR. The mechanism of biotin-dependent enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58(1):195–221.

Hu R, Sun P, Yu H, Cheng Y, Wang R, Chen X, et al. Similitudes and differences between two closely related Ficus species in the synthesis by the ostiole of odors attracting their host-specific pollinators: a transcriptomic based investigation. Acta Oecol. 2020;105:103554.

Yu H, Nason JD, Zhang L, Zheng LN, Wu W, Ge XJ. De novo transcriptome sequencing in Ficus Hirta Vahl. (Moraceae) to investigate gene regulation involved in the biosynthesis of pollinator attracting volatiles. Tree Genet Genomes. 2015;11(5).

Bublitz DC, Chadwick GL, Magyar JS, Sandoz KM, Brooks DM, Mesnage S, et al. Peptidoglycan production by an insect-bacterial mosaic. Cell. 2019;179(3):703–12.e7.

Zhu DT, Rao Q, Zou C, Ban FX, Zhao JJ, Liu SS. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal metabolic complementarity between whiteflies and their symbionts. Insect Sci. 2022;29(2):539–49.

Ju JF, Bing XL, Zhao DS, Guo Y, Xi ZY, Hoffmann AA, et al. Wolbachia supplement biotin and riboflavin to enhance reproduction in planthoppers. ISME J. 2020;14(3):676–87.

Chaisson MJ, Tesler G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): application and theory. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13.

Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(5):540–.

Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9(11).

Shen W, Le S, Li Y, Hu FQ. SeqKit: a cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One. 2016;11(10).

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D587–92.

Varani AM, Siguier P, Gourbeyre E, Charneau V, Chandler M. ISsaga is an ensemble of web-based methods for high throughput identification and semi-automatic annotation of insertion sequences in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol 2011, 12(3).

Cantalapiedra CP, Hernandez-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(12):5825–9.

Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–5.

Rozewicki J, Li SL, Amada KM, Standley DM, Katoh K. MAFFT-DASH: integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W5–W10.

Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):587–.

Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268–74.

Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun 2018, 9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Songle Fan of the South China Botanical Garden for sharing his knowledge on the ecological and molecular characteristics of figs and fig wasps. We also thank Weicheng Huang of the South China Botanical Garden for providing annotated information on Ficus hirta.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key R & D Program of China (2023YFE0100540), Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou, Guangzhou Collaborative Innovation Center on Science-tech of Ecology and Landscape (202206010058), the Chinese Academy of Sciences PIFI Fellowship for Visiting Scientists (2022VBA0002), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110981) and Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (2022ZB773).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y. supervised the project. X. X. performed the data analysis. W. Z. L. wrote the paper. A. A. H. reviewed and edited. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Xia, X., Hoffmann, A.A. et al. Evolution of Wolbachia reproductive and nutritional mutualism: insights from the genomes of two novel strains that double infect the pollinator of dioecious Ficus hirta. BMC Genomics 24, 657 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09726-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09726-2