Abstract

Background

Changshun green-shell laying hens are unique to Guizhou Province, China, and have high egg quality. Improving egg production performance has become an important breeding task, and in recent years, the development of high-throughput sequencing technology provides a fast and exact method for genetic selection. Therefore, we aimed to use this technology to analyze the differences between the ovarian mRNA transcriptome of low and high-yield Changshun green-shell layer hens, identify critical pathways and candidate genes involved in controlling the egg production rate, and provide basic data for layer breeding.

Results

The egg production rates of the low egg production group (LP) and the high egg production group (HP) were 68.00 ± 5.56 % and 93.67 ± 7.09 %, with significant differences between the groups (p < 0.01). Moreover, the egg weight, shell thickness, strength and layer weight of the LP were significantly greater than those of the HP (p < 0.05). More than 41 million clean reads per sample were obtained, and more than 90 % of the clean reads were mapped to the Gallus gallus genome. Further analysis identified 142 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), and among them, 55 were upregulated and 87 were downregulated in the ovaries. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 9 significantly enriched pathways, with the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway being the most enriched. GO enrichment analysis indicated that the GO term transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity, and the DEGs identified in this GO term, including PRLR, NRP1, IL15, BANK1, NTRK1, CCK, and HGF may be associated with crucial roles in the regulation of egg production.

Conclusions

The above-mentioned DEGs may be relevant for the molecular breeding of Changshun green-shell laying hens. Moreover, enrichment analysis indicated that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway and receptor protein tyrosine kinases may play crucial roles in the regulation of ovarian function and egg production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chicken eggs are an important food resource for humans as they contain high-quality protein, essential vitamins and minerals, and are inexpensive. Global egg consumption has tripled in the past 40 years and this trend is predicted to continue [1]. The question of how to increase egg production has consequently become a critically important question for the egg industry.

Improving the genetic potential of chickens is one of the most important strategies utilized to increase egg production. However, conventional breeding techniques based on long-term selection that use egg numbers and laying rate are usually laborious and time-consuming [2]. Currently, various high-throughput techniques that can identify genes at the genomic and transcriptomic levels have been increasingly employed for studying poultry reproduction. For instance, in goose ovaries, twenty-six genes were identified that may be related to the egg-laying process by using suppression subtractive hybridization and reverse dot-blot analysis [3]. Using a large-scale transcriptome sequencing technique, five genes in the ovarian tissues of Anser cygnoides were identified that may play important roles in determining high reproductive performance [4]. In chicken, nine genes (BDH, NCAM1, PCDHA, PGDS, PLAG1, PRL, SAR1A, SCG2, and STMN2) related to high egg production levels in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland were identified using a cDNA chip [5]. In another study, the hypothalamus and pituitary expression profiles in high- and low-yield laying chickens were analyzed by RNA-seq [6]. Seven and 39 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in the hypothalamus and pituitary, respectively, and were associated with the amino acid metabolism, glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis, and estrogen negative feedback systems. Using cDNA microarray analysis, TXN, ACADL, ING4, and ANXA2 were reported to express at higher levels in the ovarian follicles of high-yielding chicken [7]. By comparing the transcriptomes in ovarian tissues of chickens that showed greater and lesser egg-producing capacity, five candidate genes were identified to related to egg production, including ZP2, WNT4, AMH, IGF1, and CYP17A1 [8]. In addition, Mishra et al. [2] performed RNA-seq to explore the chicken transcriptome in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. Their results showed that 414, 356 and 10 DEGs were identified in the pituitary gland, ovary, and hypothalamus, respectively, between high and low-yielding chickens. These DEGs were involved in the regulation of the mTOR and Jak-STAT signaling pathways, tryptophan metabolism and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways at the HPO axis. High throughput techniques provide a fast and exact method for genetic selection and have the potential to be an appealing alternative to conventional breeding techniques.

Changshun green-shell chickens are native breeds found in Guizhou province, China. They are dual-purpose egg and meat-type chickens, and their eggs have extremely high economic value, owing to their appearance, higher protein content, better amino acid composition, and lower fat content [9]. The Hartz unit of Changshun green shell eggs is 76.39 ± 2.76 (Level AA), which is extremely significantly better than that of white shell eggs (p < 0.01), and the calcium and phosphorus content are significantly higher, while the crude fat content is significantly lower than that of white shell eggs (p < 0.01) [10]. Our previous study also found similar results (data unpublished). However, as an indigenous chicken breed, Changshun green-shell chicken shows relatively low egg production [11]. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanisms that affect the egg production of Changshun green-shell chickens. Towards this end, we conducted high-throughput RNA sequencing in the ovaries of Changshun green-shell chickens, to (1) determine the differences in the ovary mRNA transcriptomes between the low- and high-yielding Changshun green-shell laying hens, and (2) identify the critical pathways and candidate genes involved in controlling the egg production rate.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, and followed the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals, Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities (Guizhou, China). and in compliance with ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines. The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities.

Animal and sample preparation

A total of 80 Changshun green-shell layers raised in the poultry breeding farm of Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities were used in this study. At the beginning of the study (age of 240 days), the layers had similar body weights of 1.36 ± 0.14 kg. All layers were housed individually in the battery cages (36 cm-width × 48 length × 38 height) with the same feeding and management conditions throughout the study period. The room temperature was maintained at 22 ± 2℃. The light regime was 16 L:8D. Layers were allowed ad libitum access to diet and water. Diet was supplemented three times daily (7:00, 13:00, and 19:00). Egg number and egg weight were recorded every day (16:00). At 290 days of age, four high-yield (high egg production group, HP) and four low-yield individuals (low egg production group, LP) were selected from the batch of laying hens according to their laying rates. The eggshell thickness and strength were evaluated daily. In the early morning at the age of 300 days, the chickens were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital after weighing, and ovarian samples were obtained after slaughter. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until analysis. The layers had fasted overnight before being sampled.

RNA extraction, cDNA library construction, and mRNA sequencing

Total RNA from eight individuals in the two different groups (HP and LP) was extracted from the ovary samples using the Trizol reagent (Takara Bio, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In total, eight samples were obtained (one sample per individual). The concentration and quality of the total RNA were determined using a NANOdrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and electrophoresis. Sample integrity was evaluated using a microfluidic assay on the Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Library construction and RNA sequencing were performed as a fee-for-service by GENEWIZ, Inc. (Suzhou, China). Briefly, mRNAs were enriched using magnetic beads with Oligo (dT) and were randomly fragmented using a fragmentation buffer. The first strand of cDNA was synthesized with a random hexamer-primer using the mRNA fragments as a template. The second strand of cDNA synthesis was then performed using the Buffer, deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), ribonuclease H (RNase H), and DNA polymerase I. The cDNA was purified with a QiaQuick PCR extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany) and eluted with elution buffer for end repair and poly (A) addition. Sequencing adapters were ligated to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragments. The fragments were purified using agarose gel electrophoresis and enriched by PCR amplification to obtain a cDNA library. The cDNA libraries were loaded on an Illumina sequencing platform (NovaSeq 6000) for sequencing.

Data analysis

Quality control checks for the raw reads were performed using FastQC (v0.11.5). Raw reads were trimmed using the fastx_trimmer (fastx_toolkit-0.0.13.2) to obtain clean reads. Clean reads were subsequently mapped against the chicken reference genome Gallus gallus (v6.0) that was available in Ensembl v98 using HiSAT2 (v2.2.1) with default parameters. Raw counts of the genes were obtained using the htseq-count package (v0.12.3) in Python (v3.5). Raw counts were normalized using the DESeq2 package (v1.28.1) in R (v4.0.2) to obtain the gene expression level. The overall similarity between the samples was assessed using principal component analysis (PCA) in R (v4.0.2).

Identification of differentially expressed genes

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the DESeq2 package (v1.28.1) in R (v4.0.2). Genes with an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and |Log2Fold Change| ≥ 1 were assigned as differentially expressed. Hierarchical clustering and heatmaps of the DEGs were obtain using the Pheatmap package (v1.0.12) in R (v4.0.2).

KEGG pathway and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis

KEGG pathway (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) [12] and GO (http://geneontology.org) enrichment analysis of the DEGs were performed using the clusterProfiler package (v3.16.1) in R (v4.0.2), with an adjusted p < 0.05 as the screening standard.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Using total RNA, one µg was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Prime Script RT reagent Kit (Takara Bio, Dalian, China). The mRNA expression values of six candidate genes were randomly selected from the DEGs, and analyzed to verify the RNA-sequencing results. β-actin was chosen as an internal control for the normalization of expression levels. The primers used in the qRT-PCR were designed using Primer 5 (Table 1).

Gene expression was analyzed using the ABI7900 system (ABI7900 Applied Biosystems, USA), and the AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, China). The PCR protocol was initiated at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of the amplification program, with denaturation at 95 °C, 15 s, and annealing/extension at 60 °C, 60 s. At the end of the last amplification cycle, melt curves were generated to confirm the specificity of the amplification reaction. Each assay was carried out in triplicate and included a negative control. Relative quantification of the gene expression was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R software (v4.0.2, R Development Core Team 2019). Data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test after testing for the homogeneity of variance with Levene’s test. All data are presented as the mean ± SD, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Body weight, egg production, and egg quality

Details for the body weight, egg production, and egg quality are shown in Table 2. The laying rates were significantly higher in the HP than LP group (93.67 ± 7.09 vs. 68.00 ± 5.56, p < 0.01). However, egg weight, shell thickness, and strength were greater (p < 0.05) in the LP than in the HP group. In addition, the final body weight was higher (p < 0.05) in the LP group than in the HP group.

RNA sequencing quality assessment

The quality metrics of the transcriptomes are shown in Table 3. A total of 8 cDNA libraries were constructed from the ovaries of the Changshun green-shell laying hens. The raw reads and clean reads of each library were more than 42 and 41 million, respectively, except for HP-2, which had ~ 39.2 million raw reads and 39.0 million clean reads. The GC content of all samples ranged from 49.11 to 52.24 %, the base percentage of the Q20 was above 97.79 %, and the percentage of the Q30 base was above 93.55 %. In summary, the sequencing data was suitable for subsequent data analysis.

Transcriptome alignment

The results of the trimming and read mapping are shown in Table 4. The total mapped ratio between the reads and the reference genome of all the samples ranged from 90.30 to 92.37 %. The uniquely mapped ratio ranged from 86.59 to 88.89 %. The results indicated that the transcriptome data were reliable and suitable for subsequent analysis.

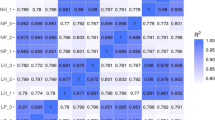

Differentially expressed genes

Samples were first analyzed using PCA. In general, the samples from the different groups were divided into two parts in the PCA score plots except for HP-4, which partially overlapped with the LP group (Fig. 1), indicating an obvious difference between the LP and HP groups. A total of 142 DEGs were identified, including 55 upregulated genes and 87 downregulated genes in the HP group (Fig. 2). The DEGs were subsequently analyzed by hierarchical clustering analysis. Samples from the same group were clustered together, and the heatmap visually reflected the differences in the gene expression patterns between the LP and HP groups (Fig. 3).

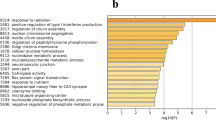

KEGG pathway and GO enrichment analysis

To further elucidate the biochemical functions of the DEGs, we performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis and GO enrichment analysis. Fifty-three out of 142 DEGs annotated by OrgDb were used for enrichment analysis. A total of nine KEGG pathways were significantly enriched (p < 0.05, Fig. 4) including those for neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, complement and coagulation cascades, Staphylococcus aureus infection, ovarian steroidogenesis, prolactin signaling pathway, PI3K − Akt signaling pathway, cAMP signaling pathway, GnRH signaling pathway, and inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels. The descriptions of these KEGG pathways are given in Table 5. A total of 220 GO terms were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05), and most of them belonged to biological processes (BP), followed by molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC). The top 25 significantly enriched GO terms for BP as well as all the significantly enriched GO terms for MF and CC are shown in Fig. 5. The descriptions of these GO terms are given in Tables S1, S2, S3. The top 25 significantly enriched BP GO terms were mainly related to the regulation of peptidase activity and endocrine process, regulation of secretion, and lipid export from cell. The significantly enriched CC GO terms were collagen-containing extracellular matrix, secretory granule lumen, cytoplasmic vesicle lumen, vesicle lumen, collagen trimer, platelet alpha granule, and specific granule. The significantly enriched MF GO terms included peptidase regulator and inhibitor activity, receptor ligand activity, transmembrane receptor protein kinase activity, and growth factor binding.

qRT-PCR validation of RNA-Seq results

To validate the RNA-seq results, six DEGs were selected for qRT-PCR analysis. These included three up-regulated genes (AMN, POMC, and CGA) and three downregulated genes (OVA, OVALX, and OVALY). The results showed that the expression trends determined by the qRT-PCR were consistent with the RNA-Seq results (Fig. 6), indicating that the RNA-seq results were reliable.

qRT-PCR validation of differentially expressed genes identified in transcriptome sequencing. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method using β-actin as an internal reference RNA. **, P < 0.01. LP, low rate of egg production group; HP, high rate of egg production group

Discussion

To determine the differences in the ovary transcriptomes of the high and low-yielding layers, HP and LP groups were assessed. Their laying rates (%) were identified as 93.67 ± 7.09 and 68.00 ± 5.56, respectively, indicating that the animal model was appropriate. We noted that HP had a lower body weight than LP. It is well known that egg production is positively correlated with energy supply [13, 14]; thus, layers of the HP group may utilize more energy for egg production instead of body weight maintenance. In addition, previous studies have shown that egg production is negatively correlated with egg weight [15, 16], the eggshell thickness is positively correlated with strength [17], and similar results were observed in our study.

Egg production traits are determined by ovarian function and are regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis [8, 18]. Thus, ovarian tissue was selected to perform the RNA-seq analysis. Significant differences were identified in the expression profiles of the ovarian tissues. According to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway comprised of multiple receptors that are associated with cell signaling [19, 20], was the most enriched. A previous study in fish found that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway could affect steroid hormone synthesis in gonads through the HPG axis [21]. In our study, the ovarian steroidogenesis pathway was identified as one of the nine significantly enriched pathways, suggesting that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway might affect egg production in chickens via a mechanism similar to that found in fish. Similar results were also previously reported for Jinghai yellow chickens [8]. In addition, Tao et al. [22] found that the same pathway was also involved in duck egg production. We identified eight DEGs that mapped to the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway (PRLR, FSHB, C3AR1, F2RL1, CGA, POMC, GALR1, and CCK) that may play an important role in the regulation of ovarian function and egg production. For the other seven significantly enriched pathways, the prolactin signaling pathway and GnRH signaling pathway have already been shown to affect avian egg production performance [23, 24]. The cAMP signaling and PI3K − Akt signaling pathways are reportedly involved in oocyte maturation and ovulation in mammals [25]. Further, the complement and coagulation cascades and inflammatory mediator regulation of the TRP channels that are associated with inflammatory responses [26], are required for ovulation in mammals [27, 28]. Thus, it is likely that these pathways may play similar roles in chicken ovaries, but further research is required to confirm this. Our results were not consistent with those of Mishra et al. [2] and Zhang et al. [8], who also conducted RNA-seq using chicken ovaries. Mishra et al. [2] identified four pathways that may play important roles in the regulation of egg production. Among them, PI3K − Akt signaling pathway alone was showed similarities with our results. Zhang et al. [8] reported five pathways, but only the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway was overlapped with our results. These conflicting results may be attributed to differences in the chicken breed used. In our study, Changshun green-shell layers were used, whereas in the Mishra et al. study [2], Chinese Luhua chickens were used, and in Zhang et al. [8], Jinghai yellow chickens were used.

The GO enrichment analysis showed that BP terms involved in regulation of peptidase and endopeptidase were most enriched. Peptidase is the term for any protein capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of a protein substrate [29]. Endopeptidases cleave the interior region of the polypeptide chain. Thus, these results suggest that endopeptidases, but not amino or carboxypeptidases, may play a key role in the regulation of chicken ovary functions. The GO terms for the following biological processes showed significant enrichment: peptidyl-tyrosine modification, peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, and positive regulation of peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation. The DEGs that mapped to these GO terms include PRLR, NRP1, IL15, BANK1, NTRK1, CCK, and HGF. The molecular function of these DEGs was transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation is the modification of post-translational proteins and plays a central role in many signaling pathways leading to cell growth and differentiation in animals [30]. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation is performed by a group of enzymes called protein tyrosine kinases, whereas receptor protein tyrosine kinases are a subclass of tyrosine kinases [31]. Using mouse ovaries, Hess et al. [32] showed that the receptor protein tyrosine kinase Ron was related to the regulation of ovary size and ovulation rates. Meanwhile, several studies have shown that the dysregulation of receptor protein tyrosine kinases is common in ovarian cancer [33,34,35], indicate the importance of receptor protein tyrosine kinases in the maintenance of ovarian function. Thus, the molecular function of transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity as well as the DEGs involved in these GO terms, should be further studied in chicken ovary tissues.

Combing the results of the KEGG pathway and GO enrichment analyses, four DEGs were selected as candidate genes, i.e., PRLR, POMC, GALR1, and F2RL1. The first three have been shown to be involved in regulating egg production in chickens. PRLR (prolactin receptor) plays an important role in the PRL signal transduction cascade and is regarded as a genetic marker for reproductive traits in poultry [36]. POMC (pro-opiomelanocortin) is a member of the prohormone family and has an important function in regulating energy balance and reproduction [37]. A recent study reported that the POMC gene had potential effects on reproduction traits in chickens [38]. GALR1 (galanin type I receptor) is widely expressed in the chicken small intestine, kidney, ovary, pancreas, spleen and throughout the oviduct. A previous study indicated that GALR1 might be responsible for mediating chicken oviduct motility and follicle ovulation [39]. The association between F2RL1 and chicken egg production has not been reported yet. F2RL1 is involved in modulation of inflammatory responses and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Previous studies have indicated that inflammatory responses are the required processes for ovulation in mammals [27, 28], which implied that the expression level of F2RL1 may also affect the egg production in Changshun green-shell chickens.

In conclusion, we characterized and evaluated the ovarian transcriptome in low and high-yielding Changshun green-shell laying hens. A total of 142 differentially expressed genes were identified, which may serve as candidate genes for the genetic improvement of egg production. Moreover, enrichment analysis indicated that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway and receptor protein tyrosine kinases may play crucial roles in the regulation of ovarian function and egg production.

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-Seq datasets are available in the Sequence Read Archive of National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/bioproject/; accession number: PRJNA685318).

Abbreviations

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- HP:

-

High egg production group

- LP:

-

Low egg production group

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- PI3K − Akt:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) − protein kinase B (Akt)

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- GnRH:

-

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- TRP:

-

Transient receptor potential

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- BP:

-

Biological processes

- MF:

-

Molecular functions

- CC:

-

Cellular components

- AMN:

-

Amnion associated transmembrane protein

- POMC:

-

Proopiomelanocortin

- CGA:

-

Glycoprotein hormones

- OVA:

-

Ovalbumin

- OVALX:

-

Ovalbumin-related protein X

- OVALY:

-

Ovalbumin-related protein Y

- HPG:

-

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

- PRLR:

-

Prolactin receptor

- FSHB:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone subunit beta

- C3AR1:

-

complement C3a receptor 1

- F2RL1:

-

F2R like trypsin receptor 1

- GALR1:

-

Galanin receptor 1

- CCK:

-

Cholecystokinin

- NRP1:

-

Neuropilin 1

- IL15:

-

interleukin-15

- BANK1:

-

B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1

- NTRK1:

-

Neurotrophic tropomyosin kinase receptor 1

- HGF:

-

Hepatocyte growth factor

References

Zaheer K. An updated review of chicken eggs: production, consumption, management aspects, and nutritional benefits to human health. Food Nutr Sci. 2015;66(13):1208–20.

Mishra SK, Chen B, Zhu Q, Xu Z, Ning C, Yin H, et al. Transcriptome analysis revealed differentially expressed genes associated with high rates of egg production in the chicken hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5976.

Kang B, Guo JR, Yang HM, Zhou RJ, Liu JX, Li SZ, et al. Differential expression profiling of ovarian genes in prelaying and laying geese. Poultry Sci. 2009;88(9):1975–83.

Ding N, Han Q, Zhao XZ, Li Q, Li J, Zhang HF, et al. Differential gene expression in pre-laying and laying period ovaries of Sichuan White geese (Anser cygnoides). Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(2):6773–85.

Shiue YL, Chen LR, Chen CF, Chen YL, Ju JP, Chao CH, et al. Identification of transcripts related to high egg production in the chicken hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Theriogenology. 2006;66(5):1274–83.

Wang C, Ma W. Hypothalamic and pituitary transcriptome profiling using RNA-sequencing in high-yielding and low-yielding laying hens. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10285.

Yang KT, Lin CY, Huang HL, Liou JS, Chien CY, Wu CP, et al. Expressed transcripts associated with high rates of egg production in chicken ovarian follicles. Mol Cell Probes. 2008;22(1):47–54.

Zhang T, Chen L, Han K, Zhang X, Zhang G, Dai G, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the ovary in relatively greater and lesser egg producing Jinghai Yellow Chicken. Anim Reprod Sci. 2019;208:106114.

Fu ZM, Wang P, Hua SS, Lan GJ. Nutritional determination and comparison of green-shell eggs and non-green-shell eggs. In: Progress in chinese poultry science research–proceedings of the 14th national symposium on poultry science. China Agricultural Science and Technology Press; 2009. p.779 – 82. In Chinese

Cheng BP, Li W, Yin X, Lin JD, Chen JH, Zhang FP. Study on Egg Quality and the Nutrition Conventional Index Measure of Changshun Green Shell Laying Hens. Guizhou Animal Husbandry and Veterinary. 2015;39:21–23. In Chinese

Xu JM. Breeding study of Changshun blue-eggshell chicken [D]. Foshan University, 2018. In Chinese

Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30.

Pérez-Bonilla A, Novoa S, García J, Mohiti-Asli M, Frikha M, Mateos GG. Effects of diet energy concentration on productive performance and egg quality of brown egg-laying hens differed in initial body weight. Poultry Sci. 2012;91(12):3156–66.

Xia B, Liu Y, Sun D, Liu J, Zhu Y, Lu L. Effects of green tea powder supplementation on egg production and egg quality in laying hens. J Appl Anim Res. 2018;46(1):927–31.

Du Plessis PHC, Erasmus J. The relationship be-tween egg production, egg weight and body weight in laying hens. World Poultry Sci J. 1972;28(3),301–10.

Neijat M, Shirley RB, Barton J, Thiery P, Welsher A, Kiarie E. Effect of dietary supplementation of Bacillus subtilis DSM29784 on hen performance, egg quality indices, and apparent retention of dietary components in laying hens from 19 to 48 weeks of age. Poultry Sci. 2019;98(11):5622–35.

Ketta M, Eva Tůmová. Relationship between eggshell thickness and other eggshell measurements in eggs from litter and cages. Ital J Anim Sci. 2017;17(1):234–39.

Farghly MFA, Mahrose KM, Rehman ZU, Yu S, Abdelfattah MG, El-Garhy OH. Intermittent lighting regime as a tool to enhance egg production and eggshell thickness in Rhode Island Red laying hens. Poult Sci. 2019;98(6):2459–65.

Lauss M, Kriegner A, Vierlinger K, Noehammer C. Characterization of the drugged human genome. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8(8):1063–73.

Cao C, Wang Z, Niu C, Desneux N, Gao X. Transcriptome profiling of Chironomus kiinensis under phenol stress using Solexa sequencing technology. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e58914.

Wang Q, Liu K, Feng B, Zhang Z, Wang R, Tang L, et al. Transcriptome of gonads from high temperature induced sex reversal during sex determination and differentiation in Chinese Tongue Sole, Cynoglossus semilaevis. Front Genet. 2019;10:1128.

Tao Z, Song W, Zhu C, Xu W, Liu H, Zhang S, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of duck ovaries with high and low egg-producing duck ovaries. Poultry Sci. 2017;96(12):4378–88.

Bédécarrats GY, Mcfarlane H, Maddineni SR, Ramachandran R. Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone receptor signaling and its impact on reproduction in chickens. Gen Comp Endocr. 2009;163(1–2):7–11.

Hu S, Duggavathi R, Zadworny D. Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying the Expression of Prolactin Receptor in Chicken Granulosa Cells. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0170409.

Conti M, Hsieh M, Zamah AM, Oh JS. Novel signaling mechanisms in the ovary during oocyte maturation and ovulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;356(1–2):65–73.

Oikonomopoulou K, Ricklin D, Ward PA. Lambris JD. Interactions between coagulation and complement—their role in inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(1):151–65.

Jesam C, Salvatierra AM, Schwartz JL, Croxatto HB. Suppression of follicular rupture with meloxicam, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: potential for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(2):368–73.

Paes VM, Liao SF, Figueiredo JR, Willard ST, Ryan PL, Feugang JM. Proteome changes in porcine follicular fluid during follicle development. J Anim Sci Biotechno. 2019;10(1):94.

Castro AMD, Santos AFD, Kachrimanidou V, Koutinas AA, Freire DMG. Solid-state fermentation for the production of proteases and amylases and their application in nutrient medium production. In: Pandey A, Larroche C, Soccol CR, Editors. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering. Elsevier; 2018. p.185–210.

Hunter T. The Croonian Lecture 1997. The phosphorylation of proteins on tyrosine: its role in cell growth and disease. Philos T Roy Soc B. 1998;353:583–605.

Du Z, Lovly CM. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):58.

Hess KA, Waltz SE, Toney-Earley K, Degen SJ. The receptor tyrosine kinase Ron is expressed in the mouse ovary and regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase levels and ovulation. Fertil Steril. 2003;80 Suppl 2:747–54.

Kumar SR, Masood R, Spannuth WA, Singh J, Scehnet J, Kleiber G, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 is overexpressed in ovarian cancer, provides survival signals and predicts poor outcome. Brit J Cancer. 2007;96(7):1083–91.

Au CW, Siu MK, Liao X, Wong ES, Ngan HY, Tam KF, et al. Tyrosine kinase B receptor and BDNF expression in ovarian cancers - Effect on cell migration, angiogenesis and clinical outcome. Cancer Lett. 2009;281(2):151–61.

Jiao Y, Ou W, Meng F, Zhou H, Wang A. Targeting HSP90 in ovarian cancers with multiple receptor tyrosine kinase coactivation. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:125.

Wilkanowska A, Mazurowski A, Mroczkowski S, Kokoszyński D. Prolactin (PRL) and prolactin receptor (PRLR) genes and their role in poultry production traits. Folia Biol (Krakow). 2014;62(1):1–8.

Hill JW, Elmquist JK, Elias CF. Hypothalamic pathways linking energy balance and reproduction. Am J Physiol Endoc Metab. 2008;294:827–32.

Liu K, Cao H, Dong X, Liu H, Wen Y, Mao H, Lu L, Yin Z. Polymorphisms of pro-opiomelanocortin gene and the association with reproduction traits in chickens. Anim Reprod Sci. 2019;210:106196.

Ho JC, Kwok AH, Zhao D, Wang Y, Leung FC. Characterization of the chicken galanin type I receptor (GalR1) and a novel GalR1-like receptor (GalR1-L). Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;170(2):391–400.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yao Lei, Ting Zhang and Ai Gao for their support in animal feeding and sample collection. And thank the reviewers for anonymous comments to improve our manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of the Science and Technology Department of the Guizhou Province (No.20172853), the Natural Science Research Project of the Education Department of the Guizhou Province (No.KY2017347, No.KY2020071), the first-class discipline construction agricultural project of the Qiannan Zhou Science and Technology Bureau (No.20188), and the Research Fund Project of Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities (QNSY2018BS011, QNSY2019RC08, qnsyzw1810).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM, ZC and WX designed this study, RM and YY conducted animal experiments. WX performed the transcriptome downstream analysis. RM conducted sample analysis and wrote the manuscript. TG, DW and FW assisted with data analysis. All authors approved this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities, and in compliance with ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, R., Yu, Yy., Gegen, T. et al. Transcriptome analysis of ovary tissues from low- and high-yielding Changshun green-shell laying hens. BMC Genomics 22, 349 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07688-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07688-x