Abstract

Background

The study of epigenetic processes and mechanisms present a dynamic approach to assess complex individual variation in obesity susceptibility. However, few studies have examined epigenetic patterns in preschool-age children at-risk for obesity despite the relevance of this developmental stage to trajectories of weight gain. We hypothesized that salivary DNA methylation patterns of key obesogenic genes in Hispanic children would 1) correlate with maternal BMI and 2) allow for identification of pathways associated with children at-risk for obesity.

Results

Genome-wide DNA methylation was conducted on 92 saliva samples collected from Hispanic preschool children using the Infinium Illumina HumanMethylation 450 K BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), which interrogates >484,000 CpG sites associated with ~24,000 genes. The analysis was limited to 936 genes that have been associated with obesity in a prior GWAS Study.

Child DNA methylation at 17 CpG sites was found to be significantly associated with maternal BMI, with increased methylation at 12 CpG sites and decreased methylation at 5 CpG sites. Pathway analysis revealed methylation at these sites related to homocysteine and methionine degradation as well as cysteine biosynthesis and circadian rhythm. Furthermore, eight of the 17 CpG sites reside in genes (FSTL1, SORCS2, NRF1, DLC1, PPARGC1B, CHN2, NXPH1) that have prior known associations with obesity, diabetes, and the insulin pathway.

Conclusions

Our study confirms that saliva is a practical human tissue to obtain in community settings and in pediatric populations. These salivary findings indicate potential epigenetic differences in Hispanic preschool children at risk for pediatric obesity. Identifying early biomarkers and understanding pathways that are epigenetically regulated during this critical stage of child development may present an opportunity for prevention or early intervention for addressing childhood obesity.

Trial registration

The clinical trial protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01316653). Registered 3 March 2011

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prevalence of childhood obesity remains a significant public health concern, especially in Hispanic populations who have the higher pediatric obesity rates [1]. Despite having increased risk of developing pediatric and adult obesity compared to other ethnic groups [2], Hispanic children are currently underrepresented in public health research. This is particularly significant as Hispanics are the most populous and rapidly growing ethnic minority in the United States, meaning this population’s health comorbidities secondary to obesity will increase healthcare costs and rates of morbidity [3, 4]. Genetic predisposition, exposure to unhealthy dietary options, and lack of adequate physical activity have all been identified as contributors to pediatric obesity [5]. However, recent literature indicates a more nuanced dynamic mechanism associated with later childhood and adult obesity that reflects the interaction between genetics, environment, and developmental stage via epigenetic modifications [6–8]. While the study of the epigenome is complex, it has the potential to inform the prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity by enhancing our understanding of timing and the mechanisms by which the genetic code could be susceptible to environmental influences [9, 10].

Genetic factors are known to affect multiple cellular and metabolic pathways underlying the development of obesity such as: adipogenesis and fat storage, adipocyte accumulation, the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) system stress response affecting cardiovascular and metabolic health, gastrointestinal tract regulatory signals, orexigenic and anorexigenic and satiety mechanisms, and insulin regulation [11, 12]. For example, there is evidence that adipocyte growth in number and size is established early, by the age of 2, and is indicative of future weight trajectory [13]. Additionally, maternal Body Mass Index (BMI) is correlated with child’s BMI status at age 6 [14] and is a better indicator of child’s BMI trajectory than child birth weight alone [6]. Current maternal BMI has been shown to be significantly associated with current child’s BMI more than other maternal socioeconomic factors (including age, marital status, education). These and other studies indicate that both current and pre-pregnancy maternal BMI are significantly associated with child’s BMI trajectory [15, 16].

However, the epigenetic mechanisms affecting potential candidate genes linked to biological processes, such as adipocyte accumulation, are relatively unknown in pediatric populations. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate the level of gene transcription, which occurs through multiple processes including DNA methylation [8, 17]. Research indicates that methyl groups can bind the genetic code in either a heritably stable or an environmentally-induced transient manner, affecting the child’s trajectory for excessive weight gain relative to height [18, 19]. There is some evidence of in utero environmentally-induced methylation associated with exposure to maternal gestational diabetes [20, 21]; maternal inadequate nutrition or insulin resistance that can cause an adaptive response in the child, resulting in epigenetic modifications signaling caloric retention [22–25]. In addition, Liu and colleagues reported that maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with alterations in offspring DNA methylation in cord blood at CpG sites annotated to genes related to the development of various complex chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease [9].

While the study by Liu et al. linked maternal weight phenotypes (normal weight; overweight; and obese) to epigenetic patterns in offspring neonatal cord blood samples [9], children between the ages 3–5 have been relatively understudied in the field of epigenetics. This is likely due to the convenience of neonatal cord blood at a younger age and the limited feasibility of obtaining blood samples until older ages. Yet, this age range is particularly important as it falls closest to the adiposity rebound stage and could play a significant role in a child’s future BMI trajectory [26]. Thus, examining the link between current maternal BMI and young children’s DNA methylation patterns, particularly among Hispanic children at high risk for obesity, can fill important gaps in current epigenetic research.

Saliva is a promising yet relatively underutilized source of DNA [27, 28]. Previous studies indicate that up to 74% of DNA in saliva comes from white blood cells, although there is high variability in individual samples [29]. Additionally, saliva is part of the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore, an important tissue to examine in obesity research [30]. Furthermore, using saliva samples rather than blood to yield epigenetic information introduces a more practical method to measure epigenetics from young children in a variety of settings, including the home and community [31].

While epigenetic patterns are tissue-dependent and results may not be consistent with other tissues [32], this study examines if there is variation in salivary DNA methylation in young children at risk for later obesity. We had three study aims: 1) to examine the association of maternal BMI phenotype with methylation patterns in preschool Hispanic child saliva by analyzing CpG sites located in genes previously associated with obesity [33]; 2) to assess if preschool child saliva would yield distinct epigenetic signatures in children at-risk for obesity compared to children of normal weight mothers; and 3) to identify biological pathways and genes in children correlated with maternal BMI. These findings could then identify potential epigenetic signatures in saliva among young children at risk for obesity, but not yet obese.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 120643). Data were collected after a parent/legal guardian signed a written informed consent, for themselves and their child, in their preferred language (English or Spanish). The clinical trial protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01316653). Registered 3 March 2011. The data for this manuscript derive from baseline salivary samples obtained prior to randomization.

Sample population study subjects

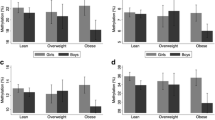

This study involved baseline saliva samples from 92 Hispanic parent-preschool children dyads, who are participating in an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT), the Growing Right Onto Wellness (GROW) Trial [34]. Children were not necessarily firstborn. Eligibility criteria for the RCT included: child 3–5 years old; child’s BMI ≥50 and <95% (at risk for obesity, but not yet obese) [35]; parental commitment to participate in a 3-year randomized controlled trial; parent age ≥18 years; parent and child in good health, without medical conditions necessitating limited physical activity as evaluated by a pre-screen; dyad considered underserved as indicated by the parent self-reporting if they or someone in their household participated in programs such as TennCare (Medicaid), CoverKids, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Food Stamps, and/or free and reduced price school meal. These children are considered to be at high risk for later childhood and adult obesity [36].

Phenotypic data

Height and weight were measured in accordance with standard anthropometric measurement procedures [37, 38]. Both values were collected twice, with the mean of the two closest measures used as the final measurement. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Table 1 outlines the phenotypic and demographic data for the sample population.

Procedures

All salivary samples were collected at baseline in the GROW RCT, before any interventions occurred, using the Oragene DNA saliva kit following a strict protocol [39]. All study members wore gloves and immediately capped specimen after collection. Samples were sent to the Vanderbilt genetic core for assessment of quality and quantity prior to storage in the Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE) core at Vanderbilt University. DNA extraction was performed as per DNA Genotek’s recommendations using the PrepIT L2P reagent. Extracted DNA was stored in individually barcoded cryovials at −80° Fahrenheit. For children, saliva was obtained using the “baby brush” approach, in which small sponges attached to plastic handles are inserted between cheek and gumline to absorb saliva [40]. The phenotypic data derived from a baseline survey and objectively measured anthropomorphic data was collected from participating mother-child pairs.

Identification of CpG Probes

We focused our analysis on 11,387 CpG sites that resided in 936 genes that have been previously reported in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to have association with childhood obesity in a Hispanic population [41]. Moreover, the original GWAS study’s initial sample size was 815 Hispanic children from 263 families [41].

Assay method

Genome-wide DNA methylation was conducted on the 92 saliva samples using the Infinium Illumina HumanMethylation 450 K BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), which interrogates >484,000 CpG sites associated with ~24,000 genes [42]. This microarray spans 99% of genes in the Reference Sequence database, with an average of 17 CpG sites per gene region, and has been previously validated for consistency [43]. Arrays were processed using standard protocol [44], with three samples randomly selected to serve as duplicates and one sample run with HapMap DNA to test functionality of reagents. Duplicates were measured for high technique consistency with Pearson correlation coefficient (>.99).

Quality control

Methylation data were quality controlled using Illumina GenomeStudio (V2011.1), Methylation module (V1.9.0). The data processing and quality control were performed using the Illumina GenomeStudio, methylation module 1.8. The GenomeStudio had built in protocols for conducting methylation array normalization. We utilized Background Subtraction, where the background value is derived by averaging the signals of built-in negative control bead types. Outliers are removed using the median absolute deviation method. Background normalization is capable of minimizing the amount of variation in background signals between arrays. This is accomplished using the signals of built-in negative controls, which are designed to be thermodynamically equivalent to the regular probes but lack a specific target in the transcriptome. Negative controls allow for estimating the expected signal level in the absence of hybridization to a specific target. The average signal of the negative controls is subtracted from the probe signals. As a result, the expected signal for unexpressed targets is equal to zero. Samples with lower than 98% call rate (i.e. <485,000 probes) were excluded.

Any non-specific cross-reacting probes, probes carrying common SNPs (MAF >1%), or any probes with p-values greater than 0.05 for more than 20% of the sample were sequentially excluded [45, 46]. One saliva sample was removed after quality control analysis (total analytic sample of n = 91). Normalization at CpG island level was performed using internal control subtracting background noise.

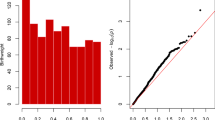

Statistical analysis

We employed an advanced statistical method called elastic net in order to select a reduced set of CpG markers for regression analyses because the number of CpG markers is substantially greater than the number of subjects [47]. The elastic net method provides variable selection to produce parsimonious and interpretable models without being severely limited by the sample size [47, 48]. While multiple test corrections are not necessary for elastic net [49–51], to demonstrate the more common presentation of results, we report Hochberg adjusted p-values [52].

The elastic net was performed prior to linear regression analysis to identify CpG sites associated with maternal BMI, due to its clinical relevance to childhood obesity for the Hispanic population [53–55]. The CpG sites selected by elastic net were then used in a univariate model to examine the individual association with maternal BMI using a linear regression model where the main outcome was child CpG methylation and the main predictor was maternal BMI, adjusting for covariates that included: child BMI, maternal age, child gender, and child age.

Pathway analysis

Functional analysis of differentially methylated genes was conducted using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) on child CpG Sites determined to be significantly methylated and associated with maternal BMI by linear regression. The analysis utilized the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (QIAGEN), a structured collection of five million findings from biomedical literature and integrated third party databases that contains 40,000 nodes with 1,480,000 edges representing cause-effect relationships. These cause-and-effect relationships take into account expression, transcription, activation, molecular modification, transport, and binding [56].

Results

Methylation analysis

The elastic net identified 17 CpG sites that were associated with maternal BMI (Fig. 1). Twelve of the 17 CpGs had increased methylation with increased maternal BMI while 5 of the 17 CpGs had decreased methylation associated with increased maternal BMI. Of these CpGs, all were significantly and independently associated with maternal BMI, as determined by linear regression (Table 2). Five CpGs were found within an enhancer region of the associated gene, 1 CpG was associated with the promotor region, and 5 CpGs were unclassified.

Pathway analysis

The top 10 canonical signaling pathways included cysteine biosynthesis, homocysteine degradation, cysteine biosynthesesis III, superpathway of methionine degradation, D-glucuronate degradation I, and Circadium Rhythm Signaling (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining DNA methylation in saliva samples obtained from preschool-age Hispanic children to investigate epigenetic patterns in children at-risk for later childhood obesity. We identified 17 CpG sites in saliva of children to be associated with maternal BMI, indicating a potential intergenerational transmission of risk for obesity in children of obese mothers.

Effect of maternal BMI phenotype on child DNA methylation in saliva

The 17 CpG probes identified by the Elastic net analysis from saliva samples are consistent with Comuzzie et al’s original GWAS study of whole blood DNA samples from 815 Hispanic children in 263 families [41]. The 17 CpG sites in Table 2 were independently and significantly associated with maternal BMI. While child age was controlled for in the linear regression analysis, these patterns may change as children age. We plan to assess epigenetic signatures and the development of childhood obesity over time in future research.

Top differentially methylated genes

Eight out of the 17 CpG sites selected by the elastic net analysis reside in genes that are associated with obesity, diabetes, or the insulin pathway by prior studies (Table 2). Specifically, the PPARGC1B and NXPH1 genes have been associated with childhood obesity in Brazil and with diabetes in the Mexican-Mestizo populations respectively. Since our population was solely Hispanic, we found it interesting that the saliva epigenetic signatures were consistent with known genetic causes of obesity and diabetes in similar populations of Hispanic origins. There are similarities between obesogenic and oncogenic states, namely cellular proliferation and inflammation, and it is interesting to note, that in this study two of the genes with significant methylation, DLC1 and CRYL1, are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. These genes have biologic plausibility of contributing to an increased risk of childhood obesity. However, because the saliva samples were derived from children within similar non-obese BMI ranges, these significant differences may indicate changes occurring in numerous different pathways even before the clinical presentation of obesity.

One unexpected finding, was that 5 of the 17 CpG sites with significant methylation have strong associations with neurological disease in the literature, specifically schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Table 2) [57, 58].

Pathway analysis

Pathway analysis identified significant enrichment of genes within pathways involved in conical signaling with respect to methylation in cysteine biosynthesis, homocysteine degradation, cysteine biosynthesis III, and methionine degradation pathways (Table 3). These pathways have been associated with obesity previously. For example, cysteine biosynthesis has been found to be positively associated with risk of obesity in Hispanic children [59], and total plasma cysteine has been independently associated with obesity and insulin resistance in the same population [60]. Furthermore, homocysteine degradation has been found to be positively associated with morbidly obese patients [61], and restriction of methionine intake has been shown to have a significant increase in fat oxidation [62]. Circadian rhythm was also identified as a top canonical pathway. Circadian rhythms regulate many biological processes and cellular metabolic pathways. Disruption of circadian rhythm has an adverse effect on metabolic function [63].

Salivary vs blood assays

Comuzzie et al. used DNA samples from whole blood in a GWAS study to identify novel genetic loci associated with the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in Hispanic children ages 4–19 years old [41]. Using these same genes in our analyses of saliva, we identified 17 CpG sites in a Hispanic pediatric population with significant methylation and associated with maternal obesogenic phenotypes. Thus, this proof of principle study demonstrated that saliva is a probable viable medium for epigenetic testing, which in this case, was consistent to whole blood findings, but we acknowledge that further testing would have to include both blood and saliva samples from the same Hispanic pediatric population to holistically assess the similarities between these 2 tissue samples. Previous studies that have investigated both of these tissues in other patient populations indicate that saliva and whole blood findings are consistent, so we would anticipate further investigations to yield similar findings [25, 26].

Limitations

Although prior literature indicates that DNA methylation levels in saliva are similar to those in peripheral blood, skin fibroblasts, and buccal swab DNA, it may not reflect the epigenome of adipose tissue, muscle, pancreas, GI system, and pituitary [64], which are implicated in the development of obesity. Furthermore, we acknowledge that we cannot assess whether these findings would be consistent in blood samples in this specific population, although prior literature seems to indicate that we would find similar epigenetic methylation patterns if tested. We did not correlate gene expression data with methylation changes, and thus can only speculate on the implications for a child’s BMI trajectory. P-adjusted values were less likely to be significant due to the large number of genes analyzed in the Illumina Human Methylation Bead Chip 450 K, making our statistically significant findings important, but likely under-identifying other potential statistically significant differential methylation patterns.

Conclusions

Results of this proof of principle study indicate that saliva is a practical way to obtain biologically plausible findings in an epigenetic analysis of preschool-age children. It is important to understand the potential pathways that could be epigenetically regulated in preschool aged children who are not currently obese but at higher risk of obesity. Moreover, saliva, an easily accessible tissue, could assist in the future identification of early biomarkers of later childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction, presenting an opportunity for prevention or early intervention for addressing childhood obesity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- GROW:

-

The Growing Right Onto Wellness Trial

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide Association Studies

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenal

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- VANTAGE:

-

the Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics

- WIC:

-

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–90.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–14.

Ramirez A, Gallion K, Despres C. Latino Childhood Obesity. In: Brennan VM, Kumanyika SK, Zambrana RE, editors. Obesity Interventions in Underserved Communities: Evidence and Directions. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. p. 43–62.

Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2847–50. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2847.

May AL, Pan L, Sherry B, Blanck HM, Galuska D, Dalenius K, Polhamus B, Kettel-Khan L, Grummer-Strawn LM. Vital signs: obesity among low-income, preschool-aged children--United States, 2008–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:629–34.

Parsons TJ, Power C, Manor O. Fetal and early life growth and body mass index from birth to early adulthood in 1958 British cohort: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2001;323:1331–5.

Grissom NM, Reyes TM. Gestational overgrowth and undergrowth affect neurodevelopment: similarities and differences from behavior to epigenetics. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2013;31:406–14.

Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:959–97.

Liu X, Chen Q, Tsai HJ, Wang G, Hong X, Zhou Y, et al. Maternal preconception body mass index and offspring cord blood DNA methylation: exploration of early life origins of disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014;55:223–30.

Dubois L, Ohm Kyvik K, Girard M, Tatone-Tokuda F, Perusse D, Hjelmborg J, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to weight, height, and BMI from birth to 19 years of age: an international study of over 12,000 twin pairs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30153.

Breton C. The hypothalamus-adipose axis is a key target of developmental programming by maternal nutritional manipulation. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:R19–31.

Bouchard L, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Faraj M, Lavoie ME, Mill J, Perusse L, et al. Differential epigenomic and transcriptomic responses in subcutaneous adipose tissue between low and high responders to caloric restriction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:309–20.

Knittle JL, Timmers K, Ginsberg-Fellner F, Brown RE, Katz DP. The growth of adipose tissue in children and adolescents. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of adipose cell number and size. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:239–46.

Brune BC, Gerlach MK, Seewald MJ, Brune TG. Early postnatal BMI adaptation is regulated during a fixed time period and mainly depends on maternal BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:798–802.

Barroso CS, Roncancio A, Hinojosa MB, Reifsnider E. The association between early childhood overweight and maternal factors. Child Obes. 2012;8:449–54.

Mamun AA, O'Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM. Change in maternal body mass index is associated with offspring body mass index: a 21-year prospective study. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:1597–606.

Feinberg AP. Epigenetics at the epicenter of modern medicine. JAMA. 2008;299:1345–50.

Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10604–9.

Herrera BM, Keildson S, Lindgren CM. Genetics and epigenetics of obesity. Maturitas. 2011;69:41–9.

Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Schmidt MM, Mullen JA, Charles MA, Pettitt DJ. Childhood obesity and metabolic imprinting: the ongoing effects of maternal hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2287–92.

Ornoy A. Growth and neurodevelopmental outcome of children born to mothers with pregestational and gestational diabetes. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2005;3:104–13.

Godfrey KM, Sheppard A, Gluckman PD, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, McLean C, et al. Epigenetic gene promoter methylation at birth is associated with child's later adiposity. Diabetes. 2011;60:1528–34.

Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–9.

Hochberg Z, Feil R, Constancia M, Fraga M, Junien C, Carel JC, et al. Child health, developmental plasticity, and epigenetic programming. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:159–224.

Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Rothman KJ, Gillman M, Fischer P, Sorensen TI. Relation between weight and length at birth and body mass index in young adulthood: cohort study. BMJ. 1997;315:1137.

Whitaker RC, Pepe MS, Wright JA, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E5.

Thompson TM, Sharfi D, Lee M, Yrigollen CM, Naumova OY, Grigorenko EL. Comparison of whole-genome DNA methylation patterns in whole blood, saliva, and lymphoblastoid cell lines. Behav Genet. 2013;43:168–76.

Abraham JE, Maranian MJ, Spiteri I, Russell R, Ingle S, Luccarini C, et al. Saliva samples are a viable alternative to blood samples as a source of DNA for high throughput genotyping. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:19.

Thiede C, Prange-Krex G, Freiberg-Richter J, Bornhauser M, Ehninger G. Buccal swabs but not mouthwash samples can be used to obtain pretransplant DNA fingerprints from recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:575–7.

Segata N, Haake SK, Mannon P, Lemon KP, Waldron L, Gevers D, et al. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R42.

Wu HC, Wang Q, Chung WK, Andrulis IL, Daly MB, John EM, et al. Correlation of DNA methylation levels in blood and saliva DNA in young girls of the LEGACY Girls study. Epigenetics. 2014;9:929–33.

Wang D, Liu X, Zhou Y, Xie H, Hong X, Tsai HJ, et al. Individual variation and longitudinal pattern of genome-wide DNA methylation from birth to the first two years of life. Epigenetics. 2012;7:594–605.

Hindorff LA MJ, Morales J, Junkins HA, Hall PN, Klemm AK, and Manolio TA. A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. Available at: www.genome.gov/gwastudies. Accessed 6 Dec 2015.

Po’e EK, Heerman WJ, Mistry RS, Barkin SL. Growing Right Onto Wellness (GROW): a family-centered, community-based obesity prevention randomized controlled trial for preschool child–parent pairs. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36:436–49.

National Center for Health Statistics and the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. 2002;11:246.

Pryor LE, Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Touchette E, Dubois L, Genolini C, et al. Developmental trajectories of body mass index in early childhood and their risk factors: an 8-year longitudinal study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:906–12.

Barkin SL, Gesell SB, Po’e EK, Escarfuller J, Tempesti T. Culturally Tailored, Family-Centered, Behavioral Obesity Intervention for Latino-American Preschool-aged Children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:445–56.

Robinson TN, Matheson DM, Kraemer HC, Wilson DM, Obarzanek E, Thompson NS, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Culturally Tailored Dance and Reducing Screen Time to Prevent Weight Gain in Low-Income African American Girls: Stanford GEMS. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:995–1004.

Nunes AP, Oliveira IO, Santos BR, Millech C, Silva LP, Gonzalez DA, et al. Quality of DNA extracted from saliva samples collected with the Oragene DNA self-collection kit. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:65.

Ng DP, Koh D, Choo S, Chia KS. Saliva as a viable alternative source of human genomic DNA in genetic epidemiology. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;367:81–5.

Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL, Voruganti VS, Haack K, Gibbs RA, et al. Novel genetic loci identified for the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51954.

Illumina Inc. Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Kit. 2015

Sandoval J, Heyn H, Moran S, Serra-Musach J, Pujana MA, Bibikova M, et al. Validation of a DNA methylation microarray for 450,000 CpG sites in the human genome. Epigenetics. 2011;6:692–702.

Bibikova M, Fan JB. GoldenGate assay for DNA methylation profiling. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;507:149–63.

Dedeurwaerder S, Defrance M, Bizet M, Calonne E, Bontempi G, Fuks F. A comprehensive overview of Infinium HumanMethylation450 data processing. Brief Bioinform. 2014;15:929–41.

Chen YA, Lemire M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Grafodatskaya D, Zanke BW, et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8:203–9.

Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2005;67:768.

Anjum S, Fourkala EO, Zikan M, Wong A, Gentry-Maharaj A, Jones A, et al. A BRCA1-mutation associated DNA methylation signature in blood cells predicts sporadic breast cancer incidence and survival. Genome Med. 2014;6:47.

Schmutz M, Zucknick M, Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Döhner H, Plass C, et al. Differential DNA Methylation Predicts Response To Combined Treatment Regimens With a DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor In Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). Blood. 2013;122:2539.

Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Koestler DC, Karagas MR, Flanagan JM, Christensen BC, Kelsey KT, et al. Review of processing and analysis methods for DNA methylation array data. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1394–402.

Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R115.

Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometricka. 1988;75:800–2.

Zhu S, Heymsfield SB, Toyoshima H, Wang Z, Pietrobelli A, Heshka S. Race-ethnicity-specific waist circumference cutoffs for identifying cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:409–15.

Colin Bell A, Adair LS, Popkin BM. Ethnic differences in the association between body mass index and hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:346–53.

Misra A, Wasir JS, Vikram NK. Waist circumference criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity are not applicable uniformly to all populations and ethnic groups. Nutrition. 2005;21:969–76.

Kramer A, Green J, Pollard Jr J, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–30.

Jo H, Schieve LA, Sharma AJ, Hinkle SN, Li R, Lind JN. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child psychosocial development at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1198–1209.

Manu P, Dima L, Shulman M, Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Correll CU. Weight gain and obesity in schizophrenia: epidemiology, pathobiology, and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132:97–108.

Elshorbagy AK, Kozich V, Smith AD, Refsum H. Cysteine and obesity: consistency of the evidence across epidemiologic, animal and cellular studies. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:49–57.

Elshorbagy AK, Valdivia-Garcia M, Refsum H, Butte N. The association of cysteine with obesity, inflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance in Hispanic children and adolescents. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44166.

Vaya A, Rivera L, Hernandez-Mijares A, de la Fuente M, Sola E, Romagnoli M, et al. Homocysteine levels in morbidly obese patients: its association with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2012;52:49–56.

Plaisance EP, Greenway FL, Boudreau A, Hill KL, Johnson WD, Krajcik RA, et al. Dietary methionine restriction increases fat oxidation in obese adults with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E836–840.

Yoshino J, Klein S. A novel link between circadian clocks and adipose tissue energy metabolism. Diabetes. 2013;62:2175–7.

Souren NY, Tierling S, Fryns JP, Derom C, Walter J, Zeegers MP. DNA methylation variability at growth-related imprints does not contribute to overweight in monozygotic twins discordant for BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:1519–22.

Wu Y, Zhou S, Smas CM. Downregulated expression of the secreted glycoprotein follistatin-like 1 (Fstl1) is a robust hallmark of preadipocyte to adipocyte conversion. Mech Dev. 2010;127:183–202.

Fan N, Sun H, Wang Y, Zhang L, Xia Z, Peng L, et al. Follistatin-like 1: a potential mediator of inflammation in obesity. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:752519.

Schmidt V, Willnow TE. Protein sorting gone wrong - VPS10P domain receptors in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2016;245:194–9.

Goodarzi MO, Lehman DM, Taylor KD, Guo X, Cui J, Quinones MJ, et al. SORCS1: a novel human type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene suggested by the mouse. Diabetes. 2007;56:1922–9.

Paterson AD, Waggott D, Boright AP, Hosseini SM, Shen E, Sylvestre MP, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a novel major locus for glycemic control in type 1 diabetes, as measured by both A1C and glucose. Diabetes. 2010;59:539–49.

Granhall C, Park HB, Fakhrai-Rad H, Luthman H. High-resolution quantitative trait locus analysis reveals multiple diabetes susceptibility loci mapped to intervals < 800 kb in the species-conserved Niddm1i of the GK rat. Genetics. 2006;174:1565–72.

Donohoe G, Morris DW, Corvin A. The psychosis susceptibility gene ZNF804A: associations, functions, and phenotypes. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:904–9.

Girgenti MJ, LoTurco JJ, Maher BJ. ZNF804a regulates expression of the schizophrenia-associated genes PRSS16, COMT, PDE4B, and DRD2. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32404.

Balog Z, Kiss I, Keri S. ZNF804A may be associated with executive control of attention. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:223–7.

Donohoe G, Rose E, Frodl T, Morris D, Spoletini I, Adriano F, et al. ZNF804A risk allele is associated with relatively intact gray matter volume in patients with schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2132–7.

Lencz T, Szeszko PR, DeRosse P, Burdick KE, Bromet EJ, Bilder RM, et al. A schizophrenia risk gene, ZNF804A, influences neuroanatomical and neurocognitive phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2284–91.

Berkel S, Marshall CR, Weiss B, Howe J, Roeth R, Moog U, et al. Mutations in the SHANK2 synaptic scaffolding gene in autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:489–91.

Berkel S, Tang W, Trevino M, Vogt M, Obenhaus HA, Gass P, et al. Inherited and de novo SHANK2 variants associated with autism spectrum disorder impair neuronal morphogenesis and physiology. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:344–57.

Kumar RA. SHANK2 redemption: another synaptic protein for mental retardation and autism. Clin Genet. 2010;78:519–21.

Won H, Lee HR, Gee HY, Mah W, Kim JI, Lee J, et al. Autistic-like social behaviour in Shank2-mutant mice improved by restoring NMDA receptor function. Nature. 2012;486:261–5.

Leblond CS, Heinrich J, Delorme R, Proepper C, Betancur C, Huguet G, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002521.

Tse MT. Neurodevelopmental disorders: exploring the links between SHANK2 and autism. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:518.

Liu Y, Niu N, Zhu X, Du T, Wang X, Chen D, et al. Genetic variation and association analyses of the nuclear respiratory factor 1 (nRF1) gene in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:777–82.

Qu L, He B, Pan Y, Xu Y, Zhu C, Tang Z, et al. Association between polymorphisms in RAPGEF1, TP53, NRF1 and type 2 diabetes in Chinese Han population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:171–6.

van Tienen FH, Lindsey PJ, van der Kallen CJ, Smeets HJ. Prolonged Nrf1 overexpression triggers adipocyte inflammation and insulin resistance. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1575–85.

Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, Kashyap S, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8466–71.

McGovern DP, Gardet A, Torkvist L, Goyette P, Essers J, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association identifies multiple ulcerative colitis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:332–7.

Sabin MA, Werther GA, Kiess W. Genetics of obesity and overgrowth syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25:207–20.

Ignoul S, Eggermont J. CBS domains: structure, function, and pathology in human proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1369–1378.

Picker JD, Levy HL. Homocystinuria Caused by Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle (WA) 1993.

Liao YC, Lo SH. Deleted in liver cancer-1 (DLC-1): a tumor suppressor not just for liver. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:843–7.

Xue W, Krasnitz A, Lucito R, Sordella R, Vanaelst L, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. DLC1 is a chromosome 8p tumor suppressor whose loss promotes hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1439–44.

Wong CC, Wong CM, Ko FC, Chan LK, Ching YP, Yam JW, et al. Deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC1) negatively regulates Rho/ROCK/MLC pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2779.

Wong CM, Yam JW, Ching YP, Yau TO, Leung TH, Jin DY, et al. Rho GTPase-activating protein deleted in liver cancer suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8861–8.

Tripathi V, Popescu NC, Zimonjic DB. DLC1 interaction with alpha-catenin stabilizes adherens junctions and enhances DLC1 antioncogenic activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2145–59.

Gong EY, Park E, Lee HJ, Lee K. Expression of Atp8b3 in murine testis and its characterization as a testis specific P-type ATPase. Reproduction. 2009;137:345–51.

Folmer DE, Elferink RP, Paulusma CC. P4 ATPases - lipid flippases and their role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:628–35.

Harris MJ, Arias IM. FIC1, a P-type ATPase linked to cholestatic liver disease, has homologues (ATP8B2 and ATP8B3) expressed throughout the body. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1633:127–31.

Cheng IK, Ching AK, Chan TC, Chan AW, Wong CK, Choy KW, et al. Reduced CRYL1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma confers cell growth advantages and correlates with adverse patient prognosis. J Pathol. 2010;220:348–60.

Chen CF, Yeh SH, Chen DS, Chen PJ, Jou YS. Molecular genetic evidence supporting a novel human hepatocellular carcinoma tumor suppressor locus at 13q12.11. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44:320–8.

Park KS, Shin HD, Park BL, Cheong HS, Cho YM, Lee HK, et al. Putative association of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1beta (PPARGC1B) polymorphism with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2006;23:635–42.

Andersen G, Wegner L, Yanagisawa K, Rose CS, Lin J, Glumer C, et al. Evidence of an association between genetic variation of the coactivator PGC-1beta and obesity. J Med Genet. 2005;42:402–7.

Queiroz EM, Candido AP, Castro IM, Bastos AQ, Machado-Coelho GL, Freitas RN. IGF2, LEPR, POMC, PPARG, and PPARGC1 gene variants are associated with obesity-related risk phenotypes in Brazilian children and adolescents. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48:595–602.

Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet. 2011;43:977–83.

Heinrich A, Lourdusamy A, Tzschoppe J, Vollstadt-Klein S, Buhler M, Steiner S, et al. The risk variant in ODZ4 for bipolar disorder impacts on amygdala activation during reward processing. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:440–5.

Craddock N, Sklar P. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381:1654–62.

Suliman SG, Stanik J, McCulloch LJ, Wilson N, Edghill EL, Misovicova N, et al. Severe insulin resistance and intrauterine growth deficiency associated with haploinsufficiency for INSR and CHN2: new insights into synergistic pathways involved in growth and metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58:2954–61.

Maeda S, Araki S, Babazono T, Toyoda M, Umezono T, Kawai K, et al. Replication study for the association between four Loci identified by a genome-wide association study on European American subjects with type 1 diabetes and susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59:2075–9.

Hu C, Zhang R, Yu W, Wang J, Wang C, Pang C, et al. CPVL/CHN2 genetic variant is associated with diabetic retinopathy in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2011;60:3085–9.

Gamboa-Melendez MA, Huerta-Chagoya A, Moreno-Macias H, Vazquez-Cardenas P, Ordonez-Sanchez ML, Rodriguez-Guillen R, et al. Contribution of common genetic variation to the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Mexican Mestizo population. Diabetes. 2012;61:3314–21.

Hayes MG, Pluzhnikov A, Miyake K, Sun Y, Ng MC, Roe CA, et al. Identification of type 2 diabetes genes in Mexican Americans through genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56:3033–44.

Takata A, Iwayama Y, Fukuo Y, Ikeda M, Okochi T, Maekawa M, et al. A population-specific uncommon variant in GRIN3A associated with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:532–9.

Shen YC, Liao DL, Chen JY, Wang YC, Lai IC, Liou YJ, et al. Exomic sequencing of the ionotropic glutamate receptor N-methyl-D-aspartate 3A gene (GRIN3A) reveals no association with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;114:25–32.

Diekstra FP, van Vught PW, van Rheenen W, Koppers M, Pasterkamp RJ, van Es MA, et al. UNC13A is a modifier of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:630.

van Es MA, Veldink JH, Saris CG, Blauw HM, van Vught PW, Birve A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 19p13.3 (UNC13A) and 9p21.2 as susceptibility loci for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1083–7.

Daoud H, Belzil V, Desjarlais A, Camu W, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. Analysis of the UNC13A gene as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:516–7.

Koppers M, Groen EJ, Van Vught PW, Van Rheenen W, Witteveen E, Van Es MA, et al. Screening for rare variants in the coding region of ALS-associated genes at 9p21.2 and 19p13.3. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1518 e5–7.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the participation of the Hispanic families involved in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by grants (U01 HL103620) with additional support for the remaining members of the COPTR Consortium (U01HL103622, U01HL103561, U01HD068890, U01HL103629) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Institute of Child Health and Development. This research was also supported by grants 5P30DK092986-03 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and 5UL1TR0045 from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series access number GSE72556 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE72556).

Authors’ contribution

Conceived and designed the experiments: SB and KT. Analyzed the data: YG. Wrote the paper: SB, KT, AN, ST. Edited and proofed the paper: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuascript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data were collected after informed consent was obtained by parent/legal guardian. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 120643).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Oelsner, K.T., Guo, Y., To, S.BC. et al. Maternal BMI as a predictor of methylation of obesity-related genes in saliva samples from preschool-age Hispanic children at-risk for obesity. BMC Genomics 18, 57 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3473-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3473-9