Abstract

Background

Ecomorphs create the opportunity to investigate ecological adaptation because they encompass organisms that evolved characteristic morphologies under similar ecological demands. For over 50 years, scorpions have been empirically assigned to ecomorphs based on the characteristic morphologies that rock, sand, vegetation, underground, and surface dwellers assume. This study aims to independently test the existence of scorpion ecomorphs by quantifying the association between their morphology and ecology across 61 species, representing 14 families of the Scorpiones order.

Results

Without a priori categorization of species into ecomorphs, we identified four groups based on microhabitat descriptors, which reflect how scorpion ecospace is clustered. Moreover, these microhabitat groups, i.e., ecotypes, have significantly divergent morphologies; therefore, they represent ecomorphs. These ecomorphs largely correspond with the ones previously described in the literature. Therefore, we retained the names Lithophilous, Psammophilous, and Pelophilous, and proposed the name Phytophilous for vegetation dwellers. Finally, we sought to map the morphology-ecology association in scorpions and found that the morphological regions most tightly associated with ecology are at the extremities. Moreover, the major trend in ecomorphological covariation is that longer walking legs and relatively slender pedipalps (pincers) are associated with sandy microhabitats, while the inverse morphological proportions are associated with rocky microhabitats.

Conclusions

Scorpion ecomorphs are validated in a naïve approach, from ecological descriptors and whole body anatomy. This places them on a more solid quantitative footing for future studies of ecological adaptation in scorpions. Our results verify most of the previously defined ecomorphotypes and could be used as a current practice to understand the adaptive significance of ecological morphology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecological adaptation is the process whereby organisms respond to environmental change by modifying their phenotype. Selection triggers adaptation to new environments and ecological niches, resulting in divergence. If the adaptations include changes in external morphology, we can observe this type of divergence in the form of recurrent morphologies—ecomorphs. Ecomorphs are groups of organisms that share a set of morphological traits associated with specific ecological requirements. Selection for these characteristic morphologies occurs in association with enhancing the ecologically relevant performance that morphology permits, also modulated by associated behaviors [1,2,3,4,5]. Striking examples of ecomorphs are predominantly known from recent adaptive radiations, such as cichlid fish [6] and Anolis lizards [7, 8]. Although with fewer examples, ecomorphs originating from older radiations are also known, such as beetles and salamanders [9, 10].

Scorpions are particularly suitable for studying ecomorphology because they have a functionally compartmentalized anatomy. As such, the functions and behaviors related to intraspecific competition, prey incapacitation, defense against predators, feeding, sensing, and sexual courtship are carried out by four anatomical regions: the pedipalps, prosoma, metasoma, and telson [11,12,13,14,15,16]. In other organisms, these functions may all be carried out using a single anatomical region, such as the head in lizards [17], while in scorpions, some functions are limited to one or more of these anatomical regions. For instance, prey capture and manipulation are restricted to the pedipalps, while prey incapacitation and defense often include the telson. Consequently, in scorpions, differences in these anatomical regions are more easily assigned to different functional demands.

Another reason makes scorpions an interesting group for studying the ecological adaptation of their morphology: they have long been assigned to ecomorphs [18,19,20,21]. These ecomorphs are considered to be associated with microhabitat use, specifically the substrate that scorpions use. The five major scorpion ecomorphs previously identified are vegetation dwellers (corticolous) [22, 23], rock climbers (lithophilous) [24, 25], hard soil fossorials (pelophilous) [23, 26], sand fossorials (psammophilous) [27, 28], and ground surface vagrants (lapidicolous) [20, 29]. Among these, there are substrate specialists and substrate generalists, i.e., habitat stenotopes and habitat eurytopes, sensu [29]. Psammophiles and lithophiles are habitat stenotopes because the extensive morphological adaptations for their preferred substrates—loose sand and rocks—make such species unfit to occupy other substrates. Lapidicolous, corticolous and pelophilous ecomorphs are eurytopic [23], with lapidicolous being the least specialized group. Other scorpiologists labeled ecomorphs differently, yet this reflects a terminological difference rather than a conceptual one [23, 30]. Some of the described morphological characteristics of these ecomorphs are considered functional adaptations. Psammophilous scorpions have longer setae and claws on their feet that may spread their mass over a larger area and reduce energy wasted on displacing loose sand during locomotion. Also, the streamlined metasoma and telson are suggested to increase sand burrowing efficiency [28] and aid in escape when animals become buried in the sand [20]. In pelophilous species, the robust, crab-like chelae are proposed to aid in burrowing, although not all species with large chelae use them for this function [29]. In addition, a lifetime spent inside a burrow is thought to reduce telson size due to its diminished use [20]. Lithophilous species are associated with dorsoventral compression and often elongation of the pedipalps, legs, and metasoma. This trend, however, seems more evident in rock crevice dwellers than in other rock microhabitats [29]. Corticolous species are also associated with some elongation of the pedipalps and legs. Other trends in corticolous scorpions seem to be more phylogenetically specific, such as the elongation of the metasoma in buthids and a general dorsoventral compression of the body in non-buthids [29]. Nonetheless, these examples are largely empirical, featuring descriptions of both regional scorpiofauna or clade-specific groups. No global study has tested whether scorpions inhabiting different habitats and continents can be grouped together based on their ecological preferences; and whether such groups also exhibit morphological coherence across the scorpion phylogeny. In sum, there is no overall data-based validation that scorpion ecomorphs exist.

Confirming that scorpion ecomorphs exist involves the simultaneous analysis of morphological and ecological traits in a phylogenetic comparative framework. Our main questions are: Can scorpions be grouped based on microhabitat preference? If so, are these groups morphologically distinct? Do these groups correspond to currently recognized ecomorphs? Which morphological traits co-vary more strongly with ecology? Given the recurrent association of characteristic pedipalp and “tail” (metasoma and telson) shapes for each ecomorph, we hypothesized that the extremities are the ecologically most important anatomical parts.

Materials and methods

Sampling and phylogeny

To explore the morphological diversity (phenotype) across the Scorpiones order, we made morphological measurements on 61 species. We measured one specimen per species, spanning approximately 70% of extant families (14 of 20), five continents (North and South America, n = 20; Eurasia, n = 15; Africa, n = 24; Oceania, n = 2). The Scorpiones families are represented by the Chaerilidae (n = 1), Buthidae (n = 23), Iuridae (n = 1), Bothriuridae (n = 3), Chactidae (n = 5), Scorpiopiidae (n = 3), Euscorpiidae (n = 1), Troglotayosicidae (n = 1), Caraboctonidae (n = 2), Hormuridae (n = 8), Urodacidae (n = 1), Diplocentridae (n = 2), Scorpionidae (n = 5) and the Vaejovidae (n = 5). The ecomorphs included are those referenced in the literature as psammophilous (e.g., Apistobuthus pterygocercus and Vejovoidus longuiunguis), lithophilous (e.g., Hadogenes paucidens and Iurus dufoureius), pelophilous (e.g., Pandinoides cavimanus and Odontobuthus doriae), corticolous (e.g., Tityus trinitatis and Opisthacanthus asper) and lapidicolous scorpions (e.g., Buthus ibericus and Bothriurus coriaceus). Specimens were selected from the scorpion collection at CIBIO in Vila do Conde, Portugal, the RMNH in Leiden, the Netherlands, and the MNHN in Paris, France.

We used recent transcriptome-based phylogenies of the Scorpiones order for our comparative analyses [31, 32]. From there, we drew an ultrametric tree with the same topology as the higher-level classifications. The interfamilial relationships are congruent in both publications, except for the position of the Vaejovidae, which was revised in [32] and adopted in this study. Species that were not present in either phylogenetic analysis were treated in one of two ways: species with members of the same genus represented in the phylogenies were placed at the position of the genus; species without genus representation were placed sister to the corresponding family clade [33, 34]. In all cases, unclear relationships between species were represented with polytomies. Branch lengths were adjusted to the tree topology, calculated using Grafen’s method [35]. We also performed the same analysis using the latest transcriptome-based phylogeny of Santibáñez-López et al. [36].

Morphological measurements

We aimed for an unbiased sampling of scorpion anatomy by measuring all anatomical regions of the scorpion body. Specifically, we did not restrict our sampling to known eco-functional traits. We used digital calipers (Absolute IP67, Mitutoyo Inc., Kawasaki, Japan) to measure 70 lengths from six anatomical regions, namely in the prosoma, mesosoma, metasoma, telson, walking legs, and pedipalps, to the nearest 0.01 mm, following Stahnke [37]. Our measurements did not include structures such as the chelicerae, carinae, tarsi, or the setal hairs. The measured species exhibit considerable size variation, and our sampling represents total body lengths from 22.1 mm in Microbuthus sp. to 158.05 mm in Ha. granulatus. To reduce the number of variables for statistical analysis, we summed trochanter and femur lengths into a “proximal leg” part and the patella, tibia, and metatarsus lengths into a “distal leg” part. This division corresponds to biomechanically functional units of the leg: on one side, the distal muscles, responsible for pretarsal (“foot”) movement occupy all distal segments until and including the patella; on the other side, most of the leg motion occurs around the femoropatellar joint [38]. The lengths of the five metasoma segments were added together, while their heights and widths were averaged. Pedipalp measurements represent averages between left and right pedipalps. For details about the measurements (description, abbreviation, and illustration), see Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Additional file 4: Table S1. The final morphological dataset consisted of 36 morphological variables, which were log-transformed before further analysis (Additional file 5: Table S2). In general, scorpions are not characterized by strong sexual dimorphism, so we did not differentiate specimens by sex. However, in those species with more substantial sexual dimorphism, males and females may have subtly different ecological roles [39].

Unlike in, e.g., herpetology, no consensually accepted single linear measurement corresponds well with overall body size in scorpions [40]. Therefore, an isometric body size (IsoSize) was calculated by projecting the 36 linear measurements on an isometric vector. We then calculated each linear measurement's regression residuals using IsoSize to obtain size-corrected traits, following [41]. Last, we calculated the degree of phylogenetic signal present in the morphological variables given the phylogeny using the function physignal of the of R package GEOMORPH. physignal provides a mathematical generalization of the Kappa statistic [42] appropriate for highly multivariate data [43].

Ecological data and microhabitat clustering

Since the conceptualization of the five scorpion ecomorphs, not all species have been assigned to one. For example, less than 50% of the taxa selected here are unambiguously assigned to an ecomorph in the literature. In cases where an ecomorph assignment can be found in the literature, the assignment is often made based on the morphological habitus of the specimens, risking circular reasoning. To overcome these limitations, we chose to forego the assignments to classical ecomorphs entirely in our analysis. Instead, we retrieved descriptors of microhabitat use from the literature. We selected descriptors referring to substrates, their arrangement, and the activities scorpions perform in them. Those most frequently encountered in the literature were used to record presence (= 1) vs. unreferenced presence (= 0) for the following 12 parameters: “compact soil”, “loose sand”, “rock surface”, “leaf-litter”, “under rocks”, “under vegetation”, “dug burrow”, “passive shelter”, “climb bushes”, “climb trees”, “rock crevices” and “hanging upside down”. Each species was assigned one or more microhabitat uses (see Additional file 5: Table S2).

We grouped species with similar microhabitat uses together into clusters. To achieve this, we used the matrix of 12 microhabitat traits in the following three steps. First, we calculated Jaccard distances between pairs of species based on all microhabitat descriptors together, using the function vegdist of R package vegan [44]. Secondly, using the obtained distance matrix, we selected the number of habitat clusters based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), using the function Mclust of R package mclust [45] (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). We selected the number of clusters corresponding to the first k preceding a plateau in BIC values. The number of clusters, four (see “Results”), was used to compute a k-means clustering. The distance matrix was used as input for a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), resulting in 26 axes. Lastly, we reviewed the ecological composition of each microhabitat cluster by calculating two matrix correlations (Spearman’s as well as Pearson’s ρ): (1) between the microhabitat traits and the PCoA scores to obtain PCoA-to-microhabitat correspondence; (2) between the resulting matrix from 1) and the k-means cluster centers to obtain microhabitat-to-cluster correspondence. Cluster terminology reproduces the different associations of each cluster to the microhabitat traits.

To visualize the scorpion ecospace, we performed multiple correspondence analyses (MCA) using function MCA of R package FactoMineR [46]. MCA uses the PCoA scores of microhabitat traits to plot barycenter points of categories (n-individual mean scores) and barycenter points of individuals (n-category mean scores) simultaneously; for visual clarity, however, only the latter were plotted.

Ecology-morphology associations

We searched for strongly eco-covarying traits by exploring which morphological traits co-vary most with ecology across all species. To this end, we applied a phylogenetic Partial Least Squares (PLS, using the phylogeny shown in Fig. 2) to the multivariate sets of ecological and morphological variables using the function phylo.integration [47,48,49] of R package GEOMORPH [50]. Here, multivariate ecology consisted of 26 microhabitat traits (PCoA axes), and multivariate morphology consisted of 36 size-corrected morphological traits. Permutations with 10,000 cycles were used to test for significance of the multivariate correlation between vectors of morphology and ecology. The resulting matrix of morphological traits with maximized ecological covariance is hereafter referred to as the matrix of eco-projected morphology.

Ecomorphological distinctiveness between microhabitat clusters

To corroborate the existence of ecomorphs in scorpions, we examined whether microhabitat clusters exhibit distinctive phenotypes as represented by ecologically correlated morphology. For this purpose, we performed a MANOVA with the matrix of eco-projected morphology as the dependent variable and microhabitat cluster as a predictor while accounting for phylogenetic autocorrelation using generalized least squares (GLS). To test for significance, we used randomization of residuals over 10,000 permutations, as implemented in the function lm.rrpp of the RRPP R package [51, 52]. Then, to identify which microhabitat clusters differed significantly, we employed distance-based testing of pairwise differences between microhabitat cluster means, as implemented in the function pairwise of RRPP [53, 54]. For illustration, we plotted group means rotated to their principal components and with 95% confidence ellipses around them, using the plotting tools of the RRPP R package.

Results

Microhabitat clusters as a proxy for ecomorphs

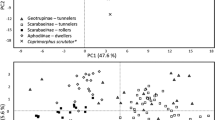

Based on the BIC, the ecological data supports the existence of four clusters (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). In terms of ecological composition, the microhabitat clusters show different associations with microhabitat traits (Table 1, Additional file 3: Fig. S3): Cluster 1 is primarily dominated by species occurring on loose sand and digging burrows; Cluster 2 mainly contains species found under vegetation, in leaf litter and using passive shelters; Cluster 3 is mostly comprised of species found in compact soil and digging burrows and Cluster 4 has a higher contribution of scorpions exploring both the crevices and the surface of rocks (Fig. 1, Table 1). It is worth noting that scorpions that rest hanging upside down are closest to cluster 4, while those climbing trees and bushes only positively correlate with cluster 2. Therefore, we named these clusters “Psammophilous”, “Phytophilous”, “Pelophilous” and “Lithophilous”, respectively, following the most common ecomorph terminology (Fig. 1, Table 1, Additional file 5: Table S2). Dimensions 1 and 2 of the MCA together capture about 40% of the microhabitat variation. Across this ecospace, the microhabitat clustering produced ecomorph groups with reduced overlap (Fig. 1).

PCoA map of scorpion ecospace. The ecospace is depicted by species (dots) colored according to ecomorph affiliation. Dots are colored based on the four clusters obtained with the R package mclust. For illustration purposes, and because it explains approximately the same variation as the second PCoA dimension, we plotted the third PCoA dimension in the vertical axis. Moreover, only species with a cos2 correlation higher than 0.70 with both dimensions for the pelophilous and phytophilous ecomorphs, and a cos2 correlation higher than 0.45 for the psammophilous and lithophilous ecomorphs are labeled. Percentage values refer to the variation explained by each axis. See Additional file 3: Fig. S3 for contributions of microhabitat variables to axis composition

Our phylogenetic tree of scorpions reveals that most scorpion families contain representatives of at least two ecomorphs (Fig. 2). In this study, the exceptions are the Vaejovidae and Diplocentridae families, as we sampled only Psammophilous and Pelophilous species respectively from, despite other ecomorphs existing in these families. This is an artifact of the limited sampling of these families, especially of the highly speciose and diverse Vaejovidae. At the superfamily level, the Iuroidea has representatives of all ecomorphs, while the Buthoidea lacks the Lithophilous ecomorph in our sampling. As a reminder, the absence of the Lithophilous ecomorph does not imply that Buthoidea scorpions are not associated with rocks. Although more prevalent in Lithophilous species, rock surfaces are also part of the Pelophilous niche (Table 1).

Phylogenetic relationships of the scorpion species included in this study. Names of the families and superfamilies are indicated. Paraphyletic families are indicated with an asterisk. Colors correspond to microhabitat ecomorph affiliation. Tree topology is based on Santibáñez-López et al. (2019) [32] and Sharma et al. (2015) [31]

The phylogenetic history of scorpions has a significant influence in their morphology. As such, the metasoma average width and height are the traits with the highest phylogenetic signal among the sampled taxa (Additional file 8: Table S5).

Ecology-morphology associations

Examination of the multivariate association between morphology and ecology yielded significantly correlated PLS vectors (r = 0.698, z = 3.228, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Vectors of ecology and morphology revealed that scorpions living under and on rock surfaces are associated with pedipalps with (dorsoventrally) higher femurs, wider patellas, and both wider and higher chelae. They are also associated with leg pairs 1 and 2 having shorter proximal parts and leg pairs 2 and 3 having shorter distal parts. Conversely, scorpions living in loose sand and digging burrows have inverse anatomical proportions (Fig. 3). As a reminder, we attributed the term eco-projected morphology to the morphological dataset resulting from this PLS; in it, the morphological traits with the highest ecological correlation, i.e., strongly eco-covarying traits, are located in the walking legs and the pedipalps of scorpions (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic PLS between scorpion ecology (Y-axis) and morphology (X-axis). Morphological traits with the highest covariation with ecology are labeled on the X-axis. Scorpion illustrations correspond to sand burrowing microhabitats (on the left, minimum extreme of the morphology PLS vector) and microhabitats found on and under rocks (on the right, maximum extreme of the morphology PLS vector). Colors correspond to microhabitat ecomorph affiliation

Ecomorphological distinctiveness between ecomorphs

MANOVA comparisons show significant differences in eco-projected morphology across the four microhabitat clusters (Table 2). Consequently, microhabitat clusters are hereafter called ecomorphs; posthoc tests show which ecomorphs are significantly different (Additional file 6: Table S3). Mean morphologies and respective confidence ellipses, estimated from the MANOVA, confirm the reduced overlap between the different ecomorphs (Fig. 4). The illustrations of four scorpions approximate the mean morphologies of each ecomorph.

Discussion

In this paper, we independently corroborate the existence of scorpion ecomorphs, and show that they are largely congruent with, but not identical to those previously defined. Moreover, we found that some parts of the scorpion body vary more strongly with ecology than others, yet not those body parts we expected.

Microhabitat clusters are ecomorphs

To start with a clean slate and avoid circular reasoning, we summarized microhabitat use in clusters rather than assigning species to previously defined ecomorphs. The number of clusters recovered in this study, four, differs from the five ecomorphs previous literature would have assigned our sampling to [29, 55]. We validated that our microhabitat clusters represent ecomorphs by showing that morphological variation is significantly different between them (Table 2). This validation accounted for two factors that mask anatomical similarity: body size and phylogeny.

Our results corroborate most ecomorphs already defined in bibliography, and thus we generally use the same names for the sake of continuity. However, we propose changing the designation “Corticolous” to “Phytophilous” as we feel that this name is more apt given the microhabitat descriptors associated with that ecomorph: “under vegetation”, “leaf-litter” and “passive shelter”. Contrary to the five ecomorphs from literature, we found our ecospace was best segmented into four clusters, where adding a fifth cluster did not improve the model. Our classification of scorpion ecomorphs, therefore, lacks the ecologically “catch-all” Lapidicolous ecomorph. The Phytophilous ecomorph, positively associated with six different microhabitats, contains the most generalist species, followed by the Pelophilous ecomorph. This trend corroborates Prendini’s [29] hypothesis that vegetation climbers and hard soil fossorials are microhabitat generalists. The Psammophilous and Lithophilous ecomorphs remain as habitat specialists, with strong correlations with a maximum of two microhabitats (Fig. 1, Table 1).

We acknowledge that these results, particularly on the number of clusters recovered and the species they consist of, are dependent on the choice and number of sampled taxa, and the prevalent phylogenetic hypothesis. After we completed the statistical analysis, a new phylogenetic hypothesis was published, placing Hadrurus outside the Caraboctonidae, among other topological changes [36]. The overdue molecular phylogenetic reappraisal of the phylogenetic relationships among scorpion taxa has recently accelerated, making this latest revision one of many to come before the high-level phylogenetic hypothesis of scorpions can be expected to converge to a stable situation. Performing our analysis again using this latest transcriptome-base phylogeny confirms the validity of scorpion ecomorphs since the same microhabitat clusters are morphologically distinct, although to a lower magnitude of correlation. Moreover, longer walking legs remain significantly associated with digging burrows and microhabitats with loose sand, but also under rocks (Additional file 9: Table S6). Under this slightly different phylogenetic hypothesis another body section gains more ecological relevance: the metasoma and telson. Wider, higher and longer metasomas and telsons are associated with compact soil and rock surface microhabitats but also with climbing bushes and trees.

Overall, we sampled 61 of the approximately 2.500 species of scorpions described: less than 3%. Although we strove for a broad sampling, families such as the species-rich radiation of the Vaejovidae and the Australo-Papuan radiations of Hormurids, Scorpiopids, and Urodacids, among others, were underrepresented. Moreover, the clustering results may be further influenced by not including representatives of the troglophilous ecomorph, and future studies should attempt to include a sufficient sample of this minor, yet more specialized, ecomorph. Future taxonomical updates will converge towards a more robust picture of the Scorpiones tree of life. We here provide a method that can accommodate virtually any phylogenetic assemblage and topology.

The extremities are rich in eco-covarying traits

The strongly eco-covarying traits, highlighted in PLS axes (Fig. 3), span two quite different anatomical regions: scorpions with relatively slenderer pedipalps and relatively longer legs in one extreme and scorpions with more robust pedipalps and shorter legs in the other. These shapes are the theoretical limits of morphological variation associated with sand fossorial or rock-dwelling microhabitats, respectively (but not rock crevice microhabitats). In fact, such rock eurytopes seem to be ecologically closer to the semilithophilous ecomorph sensu [29]. These trends, shown by the PLS, are relative. While in absolute terms, e.g., a loose sand burrowing scorpionid (a family of scorpions with typically robust pedipalps) may still have more robust pedipalps than, e.g., a rock-dwelling buthid, it will have slenderer pedipalps relative to other scorpionids (taxonomical relationships are depicted in Fig. 2).

The extremities are of major importance for scorpions to interact with the environment: the walking legs operate on the substrate in locomotion, and the pedipalps are used to navigate, obtain prey, defend and mate [56,57,58]. Different microhabitats may pose different demands on the functions of these two anatomical modules. Nonetheless, pedipalps and walking legs also share many developmental pathways [59], potentially leaving them less free to vary with ecology. Developmental linkage is more evident for structures along the body axis, as they share many developmental pathways [59, 60]. The ecomorphological paradigm predicts that the various ecomorphological associations uncovered here are likely functional, but this cannot be concluded from correlation alone. Nevertheless, these results can be an informed starting point for experimental validation of the functional value of those traits.

Based on the numerous mentions of the ecological role and morphological distinctiveness that the pedipalps and the “tail” (metasoma and telson) get in descriptions of scorpion ecomorphs, we hypothesized that in our dataset they would co-vary the most with ecology. To our surprise, variation in the metasoma and telson is not as strongly correlated with microhabitat use as the walking legs given our phylogenetic sampling and topology. As mentioned before, it looks like the appendages that directly interact with the substrate (walking legs) or to navigate through the environment (pedipalps), are more strongly associated with ecology. A potential reason for “tail” traits not emerging as part of a general ecomorphological trend in scorpions involves phylogenetic-specific associations. In fact, the phylogenetic signal of the metasoma average height and width are the highest among all the morphological measurements; and the width of the telson vesicle within the ten highest values (Additional file 8: Table S5). Accordingly, when the phylogenetic history of scorpions is not taken into account, the pedipalps and both the metasoma and the telson are the anatomical regions with the strongest association with ecology (Additional file 7: Table S4). Our data shows that morphological variation in the metasoma and telson has a stronger phylogenetic signal than an ecological signal [29] noted that the elongation of the metasoma in corticolous (i.e., phytophilous) scorpions was only verified in the Buthidae family. This observation highlights that morphological variation in the “tail” of scorpions may have a strong phylogenetic signal overall, or even vary by family. The latter may be supported by the gain in ecomorphological relevance by the “tail” in the supplementary analysis that adopts a redefined Caraboctonidae family. Conversely, this may indicate that the ecomorphological importance of walking legs proportions may have been partly obscured by phylogenetic signal.

Because we found several morphological traits associated with ecology, the use of such characters for phylogenetic inference is not advised. For example, there are species placed at the extremes of Fig. 3, such as Scorpio maurus, and Opistophthalmus wahlbergi, which belong to same family, the Scorpionidae. These species are, therefore, quite divergent in both ecology and morphology. Phylogenetically neutral morphological traits would place these two species closer together than with species from other taxonomic families.

Conclusions

This study is the first broad quantitative approach to scorpion ecomorphs. We were able to identify associations between ecology and morphology, which transcend taxonomical relatedness. The ecomorphological paradigm predicts that the various associations we uncovered are likely functional, but correlation alone is not conclusive evidence. Nevertheless, these results can be an informed starting point for experimental validation of the functional value of those traits.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional information files.

References

Arnold SJ. Morphology, performance and fitness. Am Zool. 1983;23:347–61.

Huey RB, Kingsolver JG. Evolution of thermal sensitivity of ectotherm performance. Trends Ecol Evol. 1989;4:131–5.

Huey RB, Hertz PE, Sinervo B. Behavioral drive versus behavioral inertia in evolution: a null model approach. Am Nat. 2003;161:357–66.

Price SA, Holzman R, Near TJ, Wainwright PC. Coral reefs promote the evolution of morphological diversity and ecological novelty in labrid fishes. Ecol Lett. 2011;14:462–9.

Price SA, Wainwright PC, Bellwood DR, Kazancioglu E, Collar DC, Near TJ. Functional innovations and morphological diversification in parrotfish. Evol Int J Org Evol. 2010;64:3057–68.

Turner GF. Adaptive radiation of cichlid fish. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R827–31.

Losos JB. Ecomorphology, performance capability, and scaling of West Indian Anolis lizards: an evolutionary analysis. Ecol Monogr. 1990;60:369–88.

Irschick DJ, Vitt LJ, Zani PA, Losos JB. A comparison of evolutionary radiations in mainland and Caribbean Anolis lizards. 1997.

Rabosky D, Adams D. Rates of morphological evolution are correlated with species richness in salamanders. Evol Int J Org Evol. 2012;66:1807–18.

Maruyama M, Parker J. Deep-time convergence in rove beetle symbionts of army ants. Curr Biol. 2017;27:920–6.

Tallarovic S. Reproductive and aggressive behaviors in the giant hairy desert scorpion. Oregon State University; 2000.

Casper G. Prey capture and stinging behavior in the emperor scorpion, Pandinus imperator (Koch) (Scorpiones, Scorpionidae). J Arachnol. 1985.

Jiao G, Zhu M. Prey capture behaviour in Heterometrus petersii (Thorell, 1876) (Scorpiones: Scorpionidae). Euscorpius. 2009;2009:1–5.

van der Meijden A, Lobo Coelho P, Sousa P, Herrel A. Choose your weapon: defensive behavior is associated with morphology and performance in scorpions. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78955.

Warburg M. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of intra-and interspecific behavioural patterns among scorpions. J Ethol. 1998;16:115–21.

Simone Y, Meijden A van der. Armed stem to stinger: a review of the ecological roles of scorpion weapons. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2021;27.

Aerts P, De Vree F, Herrel A. Ecomorphology of the lizard feeding apparatus: a modelling approach. Netherlands J Zool. 1997;48:1–25.

Hadley NF. Adaptational biology of desert scorpions. J Arachnol. 1974;2:11–23.

Polis GA, McCormick SJ. Patterns of resource use and age structure among species of desert scorpion. J Anim Ecol. 1986;55:59.

Polis GA. The biology of scorpions. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1990.

Bradley R. The behavioural ecology of scorpions—a review. Aust Arachnol. 1988;5:23–36.

Newlands G. Arachnida (except Acari). In: Werger MJA, editor. Biogeography and ecology of southern Africa. The Hague: Springer, Dordrecht; 1978. p. 685–702.

Lamoral B. The scorpions of Namibia (Arachnida-Scorpionida). Ann Natal Museum. 1979;23:497–784.

Newlands G. A revision of the scorpion genus Hadogenes Kraepelin 1894 (Arachnida: Scorpionidae) with a checklist and key to the species. 1980.

Newlands G. Ecological adaptations of Kruger National Park sgop.pionids (Arachnida: Scorpionides). Koedoe. 1972;15:37–48.

Williams SC. Burrowing activities of the scorpion Anuroctonus phaeodactylus (Wood) (Scorpionida: Vejovidae). Proc Calif Acad Sci. 1966;34:419–28.

Lawrence F. A new genus of psammophile scorpion and new species of Opisthophthalmus from the Namib desert. Scientific Papers of the Namib Desert Research Station. 1969;48:105–16.

Newlands G. Notes on psammophilous scorpions and a description of a new species (Arachnida: Scorpionides). Ann Transvaal Museum. 1972;27:241–54.

Prendini L. Substratum specialization and speciation in southern African scorpions: the Effective Hypothesis revisited. Scorpions 2001: In memorian Gary A Polis. 2001; 113–38.

Bradley R. The behavioural ecology of scorpions—a review. In: Austin AD, Heather N, editors. Australian entomological society. Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & Co; 1988. p. 23–36.

Sharma P, Fernandez R, Esposito L, Gonzalez-Santillan E, Monod L, Ferna R. Phylogenomic resolution of scorpions reveals multilevel discordance with morphological phylogenetic signal. Proc R Soc B. 2015;282B:20142953–20142953.

Santibáñez-López CE, González-Santillán E, Monod L, Sharma PP. Phylogenomics facilitates stable scorpion systematics: reassessing the relationships of Vaejovidae and a new higher-level classification of Scorpiones (Arachnida). Mol Phylogenetics Evol. 2019;135:22–30.

Soleglad ME, Fet V. High-level systematics and phylogeny of the extant scorpions (Scorpiones: Orthosterni). Euscorpius. 2003;2003:1–56.

Coddington JA, Giribet G, Harvey MS, Prendini L, Walter DE. Arachnida. In: Cracraft J, Donoghue MJ, editors. Assembling the tree of life. Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 296–318.

Grafen A. The uniqueness of the phylogenetic regression. J Theor Biol. 1992;156:405–23.

Santibáñez-López CE, Ojanguren-Affilastro AA, Sharma PP. Another one bites the dust: taxonomic sampling of a key genus in phylogenomic datasets reveals more non-monophyletic groups in traditional scorpion classification. Invert Syst. 2020;34:133–43.

Stahnke H. Scorpion nomenclature and mensuration. Entomol News. 1970;81:297–316.

Shultz JW. Morphology of locomotor appendages in Arachnida: evolutionary trends and phylogenetic implications. Zool J Linn Soc. 1989;97:1–55.

McLean CJ, Garwood RJ, Brassey CA. Sexual dimorphism in the Arachnid orders. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5751.

Fox GA, Cooper AM, Hayes WK. The dilemma of choosing a reference character for measuring sexual size dimorphism, sexual body component dimorphism, and character scaling: cryptic dimorphism and allometry in the scorpion Hadrurus arizonensis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120392.

Coelho P, Kaliontzopoulou A, Rasko M, van der Meijden A. A ‘striking’ relationship: scorpion defensive behaviour and its relation to morphology and performance. Funct Ecol. 2017;31:1390–404.

Blomberg SP, Garland T, Ives AR. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution. 2003;57:717–45.

Adams D. A generalized K statistic for estimating phylogenetic signal from shape and other high-dimensional multivariate data. Syst Biol. 2014;63:685–97.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2020.

Scrucca L, Fop M, Murphy TB, Raftery AE. mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. The R J. 2016;8:289–317.

Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw. 2008;25:1–18.

Adams D, Collyer M. On the comparison of the strength of morphological integration across morphometric datasets. Evolution. 2016;70:2623–31.

Adams D, Collyer M. Comparing the strength of modular signal, and evaluating alternative modular hypotheses, using covariance ratio effect sizes with morphometric data. Evolution. 2019;73:2352–67.

Rohlf FJ, Corti M. Use of two-block partial least-squares to study covariation in shape. Syst Biol. 2000;49:740–53.

Adams D, Collyer M, Kaliontzopoulou A, Baken E. Geomorph: Software for geometric morphometric analyses. R package version 3.3.2. 2021.

Collyer M, Adams D. RRPP: an R package for fitting linear models to high-dimensional data using residual randomization. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9:1772–9.

Collyer M, Adams D. RRPP: linear model evaluation with randomized residuals in a permutation procedure. R package version 0.4. 0. 2019.

Collyer M, Sekora D, Adams D. A method for analysis of phenotypic change for phenotypes described by high-dimensional data. Heredity. 2015;115:357–65.

Adams D, Collyer M. Phylogenetic ANOVA: group-clade aggregation, biological challenges, and a refined permutation procedure. Evolution. 2018;72:1204–15.

Sibly RM. Life history. In: Polis GA, editor. Metabolic ecology: a scaling approach. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2012. p. 57–66.

Simone Y, van der Meijden A. Armed stem to stinger; a review of the ecological roles of the weaponry of scorpions. J Venom Anim Toxins. 2021;

Fet V, Sissom W, Lowe G, Braunwalder M. Catalog of the scorpions of the world (1758–1998). New York: New York Entomological Society; 2000.

Brownell PH, Polis GA. Scorpion biology and research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Farley RD. Development of segments and appendages in embryos of the desert scorpion Paruroctonus mesaensis (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae). J Morphol. 2001;250:70–88.

Alberch P. Ontogenesis and morphological diversification. Am Zool. 1980;20:653–67.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Wilson Lourenço at the MNHN in Paris and Karen van Dorp at the RMNH Leiden for access to the scorpions in the collections. Thanks also to Bárbara Santos for her assistance in measuring specimens. The authors are grateful to Michael Collyer for his availability to troubleshoot our analysis using the RRPP R package.

Funding

PC is financed through FCT, under fellowship number SFRH/BD/101998/2014. AK is financed by a Ramón y Cajal research Grant co-funded by the Spanish State Research Agency and the European Social Fund (RYC2019-026688-I/AEI/10. 13039/501100011033). PS is supported by a Grant from project PORBIOTA—Portuguese E-Infrastructure for Information and Research on Biodiversity (POCI-01-0145- FEDER-022127), supported by the Operational Thematic Program for Competitiveness and Internationalization (POCI), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). AvdM is financed through FCT, I.P. under contract number DL57/2016/CP1440/CT0009. Work supported by National Funds through FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia in the scope of the project UIDP/50027/2020. This work is also funded by FEDER funds through the Operational Program for Competitiveness Factors—COMPETE and by National Funds through FCT under the project FCT-PTDC/BIA-EVF/2687/2012 and FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-028340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC, AvdM, and AK conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; PC, AvdM, PS, and MS collected the data; PC and AK analyzed the data; PC, AvdM, and AK led the writing of the manuscript; All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Arrows represent the distance measured by calipers. Measurements of the left column are colored according to their anatomical region: pedipalps, prosoma, mesosoma, metasoma, and walking legs).

Additional file 2.

Model-Based Clustering performance for clustering of samples via the BIC for up to 10 components (i.e. clusters) (BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion). EII - VVI refer to the names of the models used for clustering fitting.

Additional file 3.

The ecospace is depicted by species (circles) and microhabitat use (triangles) and ecomorph groups (squares) colored according to ecomorph affiliation. The intensity of the colors corresponds to the cos2 correlation with both dimensions. Percentage values refer to the variation explained by each axis. Ecomorph datapoints are supplementary information that does not contribute to axis composition.

Additional file 4.

Abbreviations of the linear morphological measurements. Name abbreviation, description, and anatomical location of the morphological measurements. The statistical analysis uses a data reduction from 70 to 36 morphological variables.

Additional file 5.

Microhabitat use and morphological dataset. Absolute values of 36 linear measurements, 12 microhabitat variables, and the ecomorphs resulting from microhabitat clustering.

Additional file 6.

Pairwise distances between Least Squares Regression (LSR) means calculated by a MANOVA of eco-projected morphology.

Additional file 7.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) loadings. Loadings of the first Partial Least Squares vector (PLS1) for each multivariate block (morphology and microhabitat) in two scenarios: when phylogeny is taken into account (left columns) and when phylogeny is not taken into account (right columns).

Additional file 8.

Phylogenetic signal of the morphological measurements. Blomberg's K values of phylogenetic signal and respective test of significance (P value).

Additional file 9.

Revised Partial Least Squares (PLS) loadings. Loadings of the first PLS (PLS1) for each multivariate block (morphology and microhabitat) corrected for the phylogeny of "Santibáñez-López et al. [36].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Coelho, P., Kaliontzopoulou, A., Sousa, P. et al. Reevaluating scorpion ecomorphs using a naïve approach. BMC Ecol Evo 22, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01968-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01968-0