Abstract

Background

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is one of the most important species for temperate pastoral agriculture, forming associations with genetically diverse groups of mutualistic fungal endophytes. However, only two taxonomic groups (E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2) have so far been described. In addition to these two well-characterised taxa, a third distinct group of previously unclassified perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes was identified as belonging to a putative novel taxon (or taxa) (PNT) in a previous analysis based on simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker diversity. As well as genotypic differences, distinctive alkaloid production profiles were observed for members of the PNT group.

Results

A detailed phylogenetic analysis of perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes using components of whole genome sequence data was performed using complete sequences of 7 nuclear protein-encoding genes. Three independently selected genes (encoding a DEAD/DEAH box helicase [Sbp4], a glycosyl hydrolase [family 92 protein] and a MEAB protein), none of which have been previously used for taxonomic studies of endophytes, were selected together with the frequently used ‘house-keeping’ genes tefA and tubB (encoding translation elongation factor 1-α and β-tubulin, respectively). In addition, an endophyte-specific gene (perA for peramine biosynthesis) and the fungal-specific MT genes for mating-type control were included. The results supported previous phylogenomic inferences for the known species, but revealed distinctive patterns of diversity for the previously unclassified endophyte strains, which were further proposed to belong to not one but two distinct novel taxa. Potential progenitor genomes for the asexual endophytes among contemporary teleomorphic (sexual Epichloë) species were also identified from the phylogenetic analysis.

Conclusions

Unique taxonomic status for the PNT was confirmed through comparison of multiple nuclear gene sequences, and also supported by evidence from chemotypic diversity. Analysis of MT gene idiomorphs further supported a predicted independent origin of two distinct perennial ryegrass-associated novel taxa, designated LpTG-3 and LpTG-4, from different members of a similar founder population related to contemporary E. festucae. The analysis also provided higher resolution to the known progenitor contributions of previously characterised perennial ryegrass-associated endophyte taxa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Lolium, which belongs to the sub-family Pooideae (cool-season grasses) of the grass and cereal family Poaceae, includes several important forage and turf species [1,2]. Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is extensively cultivated for pasture production on a global basis [3,4]. Like other cool-season grasses, perennial ryegrass is often infected with clavicipitaceous fungal endophytes that include both sexual and asexual taxa [5-7]. The asexual (anamorphic) taxa were previously assigned to a separate genus (Neotyphodium), but in accord with general recommendations for fungal taxonomy, have been recently been combined with the sexual (teleomorphic) taxa within a single genus, designated Epichloë [8]. Asexual Epichloë endophytes colonise the intercellular spaces of leaf sheaths, culms, and rhizomes, and infrequently the surface of leaf blades, without inducing obvious pathological symptoms [9]. These asexual endophytes do not produce stromata, and rely solely on the host plant for transmission [10,11]. The vegetative phase of growth for sexual is similar to that of asexual Epichloë species [12], but in the sexual stage, stromata are formed around the developing inflorescences and prevent emergence of the floral meristem [7,12].

Asexual Epichloë species form mutualistic associations with their hosts [13,14]. Benefits for the host related to abiotic stress tolerance are obtained through enhanced growth, increased seedling vigour and persistence, particularly under water stress and nutrient deficiency [15,16]. The endophyte also confers biotic stress tolerance to the host grass, through production of several classes of biologically active alkaloids. Peramine and loline produced by the endophyte are active against insect pests, while lolitrem B and ergovaline are toxic to mammalian herbivores [17-19]. Conversely, as part of the symbiosis, the plant provides certain benefits to the endophyte such as shelter, nutrition, reproduction and distribution [14,20,21].

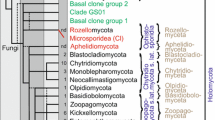

Perennial ryegrass has been found to be host to two distinct fungal endophyte taxa: Epichloë festucae var. lolii (Latch, Christensen and Samuels) Bacon and Schardl syn. N. lolii (Latch, Christensen and Samuels) Glenn, Bacon and Hanlin [22] and Lolium perenne taxonomic group 2 (LpTG-2) [23]. Distinct taxonomic groups of asexual Epichloë endophytes are proposed to have evolved either by direct evolution from a single teleomorphic species, probably due to loss of the sexual state, or through interspecific hybridisation events between either sexual species or distinct sexual and asexual lineages, the latter generating heteroploid genetic constitutions [24-27]. The haploid taxon E. festucae var. lolii has been identified as a direct derivative of Epichloë festucae Leuchtm., Schardl & M. R. Siegel while the heteroploid LpTG-2 arose as an interspecific hybrid between E. festucae var. lolii and E. typhina (Pers.) Tul. & C. Tul. [24,26].

Previous phylogenetic characterisation studies of both sexual and asexual Epichloë species have largely been based on the use of partial sequences of genes encoding highly conserved proteins such as tefA, tubB and act1 (actin), including both relatively invariant coding sequences and more diverse intronic regions [25,28,29]. In addition, sequence diversity of the genes responsible for alkaloid biosynthesis has also been employed for phylogenetic analysis. Specifically, the perA gene, which is responsible for peramine production, has been identified as potentially exhibiting a higher rate of molecular evolution than ‘house-keeping’ genes, permitting resolution of close taxonomic relationships [30]. Gene sequences of perA, along with several of the more conserved genes, have previously been used to study relationships between endophytes of perennial ryegrass and members of the closely related grass genus, Festuca (fescues) [30,31], including elucidation of the ancestral lineages that have contributed to contemporary hybrid endophytes [32]. In addition, use of different approaches such as morphological and physiological variation of cultured endophytes, isoenzyme variation and gene-based sequence analysis have been used to define and promote new taxonomic groups [33]. Due to advances in genomic technologies, complete sequences from various genes have increased the reliability of phylogenetic inference [30]. However, differences in performance for phylogenetic studies have been reported between individual genes [1]. This limitation may be addressed through the use of multiple gene sequences, as a proxy for variation across the entirety of the endophyte genome.

Molecular genetic markers based on sequence polymorphism may also be used to address issues of endophyte diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny [1]. A large set of SSR marker loci has been developed for the identification and assessment of genetic diversity among asexual Epichloë endophytes [34]. In previous studies of perennial ryegrass-derived endophyte diversity based on variation of 18 such SSR markers, three distinct groups of perennial ryegrass endophytes were observed [35]. In addition to the well-characterised taxa, E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2, a third distinct group of previously unclassified endophytes was identified as belonging to one or more PNT. However, SSR variation, although indicative, is of only limited value for definition of taxonomic groupings, due to the generation of data suitable for phenetic, rather than phylogenetic, analysis. Nonetheless, putative novel taxa of fescue-derived heteroploid endophytes that were predicted on the basis of SSR-based phenetic dendrograms [36] were demonstrated to be genuinely distinct on the basis of subsequent phylogenomic studies [30].

The present study describes the evolutionary relationships between 19 representative perennial ryegrass-associated endophyte strains belonging to the known taxa E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2, and the uncharacterised PNT, as well as several putative ancestral sexual Epichloë species. The phylogenetic analysis was based on 7 full-length gene sequences derived from whole genome sequence datasets, including tefA, tubB and perA which were previously used for a corresponding study of fescue-derived endophytes [30]. In addition, complete sequences of three further independently selected nuclear genes (for which full-length sequence coverage is available for all strains analysed) were included: DEAD/DEAH box helicase (Sbp4), glycosyl hydrolase (family 92 protein) and MEAB protein. DEAD/DEAH box helicases are a family of proteins which are involved in various processes of RNA metabolism [37]. Glycoside hydrolases are enzymes present in a wide range of organisms which hydrolyse the glycosidic bond between a carbohydrate and another compound, such as a second carbohydrate, a protein, or a lipid [38]. MEAB is a protein that mediates nitrogen catabolite repression in fungi [39]. Finally, the mating type (MT) genes, which play an important role in evolution of fungal species through control of sexual compatibility, were also included.

Methods

Selection of endophyte strains

A total of 19 endophyte strains that form associations with perennial ryegrass were used for the phylogenetic analysis (Table 1). The genetic properties [40] and phenotypic [39] properties of NEA2, NEA3 and NEA4 were formerly described. All other strains were as previously defined [35], apart from E1, which was originally isolated from an accession of chewings fescue (F. rubra ssp. commutata Gaudin). However, E1 was shown to be capable of stable establishment after introduction into multiple genotypes of perennial ryegrass through artificial inoculation into regenerating meristem-derived callus [33] (data not shown). E1 displays a closer similarity to previously described PNT genotypes such as NEA12 than to representatives of E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2, and so was included in this study, but is nonetheless distinct in genetic terms [35].

Generation and assembly of genome sequence data

Genomic paired-end reads generated by sequencing libraries prepared using the TruSeq™ low-throughput (LT) DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina Inc, San Diego, California, USA) were used to generate assemblies of ryegrass-associated endophyte genomes. Low-quality sequence reads were filtered out using a custom python script, which calculates quality statistics and stores trimmed reads in several fastq files. Genome assemblies of endophytes C09, E1, NEA4 and NEA11 were obtained through VelvetOptimiser (version 2.2.0) using default parameters except for hash length (K-mer sizes) which was in the range of 31 to 71. Previously generated genome assemblies from other endophyte strains [40,41] were used in this analysis.

Identification of gene sequences

Presence and copy number of tefA, tubB, perA, DEAD/DEAH helicase, glycosyl hydrolase, MEAB protein and MT genes in each endophyte genome were initially identified through nucleotide BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (version 2.2.25) analysis [42] using contigs from the optimised velvet assembly of total reads as the database which was queried with the following reference sequences (Genbank accession numbers: tubB: AY722412 from E. festucae Fl1; tefA: FJ660614 from E. festucae E2368; perA: AB205145 from E. festucae Fl1; glycosyl hydrolase, family 92 protein: XM_006669157.1 from Cordyceps militaris CM01; DEAD/DEAH box helicase (Sbp4): XM_007820576.1 from Metarhizium anisopliae ARSEF 23; MEAB protein: XM_007825059.1 from M. anisopliae ARSEF 23; MT genes: FJ717711.1 (mtAA), HQ680588.1 (mtAB), HQ680587.1 (mtAC) from E. festucae E2368 and HQ680590.1 (mtBA) from E. festucae Fl1. Following identification of contigs and gene coordinates for selected genes within the genomes of the haploid strains (E. festucae var. lolii and PNT) using corresponding reference genes, the contig and subsequently, the relevant gene sequence was extracted using fastacmd (version 2.2.24) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and EMBOSS extractseq (version 6.3.1) (gwilliam@hgmp.mrc.ac.uk), respectively. A similar approach was used to extract corresponding gene sequences from the genomes of E. typhina 9340, 9636 and E. baconii 9707 based on the relevant databases. Data for representative Epichloë species isolates was extracted from genome sequence data available at http://www.endophyte.uky.edu/ [43].

A different approach was used to extract genes from heteroploid strains (LpTG-2), due to the presence of two copies for each gene. Corresponding gene sequences of the predicted progenitors, E. festucae var. lolii (SE) and E. typhina (9636) were used as references for mapping of all sequencing reads from LpTG-2 strains using Bowtie (version 1.0.0) (Langmead). Mapped reads were assembled using velvet (version 1.1.06) [44] using the corresponding gene as the reference to obtain two copies for each LpTG-2 strain.

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences of all selected endophyte strains were aligned using MUSCLE, built-in version of MEGA (version 5.2.2) [45]. Alignments were checked manually for ambiguities and adjusted if necessary. To construct the tree topology, maximum likelihood (ML) and neighbour-joining (NJ) methods were used as implemented in MEGA 5.2.2 with default parameters. Positions containing gaps or missing data were eliminated in constructing phylogenetic trees. Robustness of inferred phylogenies was estimated by bootstrap replication (1,000 replicates), and branches receiving less than 60% of replicates were collapsed.

For the sake of clarity, gene copies of LpTG-2 strains were appended with the suffixes GC1 and GC2, reflecting phylogenetic affinity with E. festucae var. lolii and E. typhina, respectively. Megablast searches [40] using tubB, tefA and perA sequences were performed in GenBank nucleotide sequence database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to identify the closest matching sequences of Epichloë species, which were added to the sequence alignment. Accession numbers for GenBank-derived sequences are provided in each phylogram next to the isolate name.

Phylogenetic analysis was also performed with the concatenated sequences. The sequences of all, except MT, genes were concatenated in the order of tefA, tubB, perA, DEAD/DEAH helicase, glycosyl hydrolase and MEAB protein into a multi-gene alignment which was then aligned using MUSCLE. Phylogenetic topology was constructed using the same methods as described above.

Results

Assembly of genome sequence data

Statistics for genome assemblies of perennial ryegrass-associated endophyte strains are provided in Additional file 1.

Identification of nuclear gene copies

BLASTN analysis, as described, was used to identify the presence of the 7 selected gene sequences in the genomes of all candidate strains and reference sexual Epichloë species. Single copies of each gene were identified for all isolates of E. festucae var. lolii and PNT, reflecting haploid genome structures. In contrast, two copies of each gene were observed for both representatives of taxon LpTG-2. Complete copies of the perA gene were identified in E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2 strains, but all PNT representatives showed the presence of a 1223 bp deletion at the 3’-end of the gene. Furthermore, apart from strain E1, all PNT strains contained a premature stop codon at coordinate 2923 bp within the perA gene sequence.

Phylogenetic characterisation based on individual gene sequences

Phylograms were constructed on an individual gene basis using the ML and NJ methods. In all instances, except for the MT genes, the phylogram structure revealed three major distinct sequence clades. The single gene copies from E. festucae var. lolii and GC1 from LpTG-2 were located in the first clade, while LpTG-2 GC2 was located in the second clade. For all phylograms, the third clade contained single gene copies from PNT representatives, except for that generated from tefA sequences, in which strain E1 was grouped with the E. festucae var. lolii strains in clade 1. The separation of the three clades was supported by >80% bootstrap values in all instances (results not shown). For LpTG2-derived sequences, lower variability was observed between GC1 representatives from the alternate strains than for those from GC2.

The significant levels of divergence between clades suggest different evolutionary origins. In order to identify potential progenitor genomes among contemporary teleomorphic taxa, phylogenetic analysis was repeated to include representative isolates of Epichloë species, and phylograms were constructed using both ML and NJ methods. All trees resulting from phylogenetic analysis using each method were congruent in topology, which indicated similar evolutionary relationships in respect of both E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2 (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Again, separation of PNT strains from the other asexual taxa was supported by >76% bootstrap values in the ML analysis and >73% bootstrap values in the NJ analysis, apart from for tubB, which displayed moderate bootstrap support (62% for ML analysis and 66% for NJ analysis).

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of tefA gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates, with bootstrap values (>60% from 1,000 replicates) shown on nodes. Endophyte taxa are colour-coded as indicated in the legend. The GenBank accession numbers of the tefA genes derived from ryegrass-associated endophytes are provided in Additional file 4, and GenBank accession numbers of the reference sequences are provided following taxon and strain identities.

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of tubB gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of perA gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of glycosyl hydrolase gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of MEAB gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of DEAD gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

In general, the single gene copies characteristic of E. festucae var. lolii and PNT-derived strains were most closely related to those of strains of E. festucae. However, contrasting patterns of affinity with specific E. festucae isolates were observed between the different selected genes. In the tubB-specific phylogram, E. festucae strain E2368- and E. festucae Fl1-derived sequences exhibited a similar degree of affinity to those of each of the haploid taxa. In contrast, in the perA-specific phylogram, E. festucae var. lolii-derived sequences were grouped more closely with E. festucae Fl1, while PNT-derived sequences were located closer to E. festucae strain E2368. Furthermore, strain E1 formed a sister group with E. festucae strain E2368. In the phylograms derived from the glycosyl hydrolase, MEAB protein and DEAD-box helicase genes, both E. festucae Fl1 and E. festucae strain E2368 were closer to the PNT genotypes. Finally, a higher similarity between E. festucae var. lolii and both E. festucae strains (E2368 and Fl1) was observed in the tefA-based phylogenetic tree.

The genomes of the heteroploid LpTG-2 endophyte contained two distinct copies for each gene, reflecting the hybrid origin of this taxon. While GC1 was closely related to those of E. festucae var. lolii, GC2 showed affinity to the corresponding sequences from multiple isolates of E. typhina related sequences. In all individual gene-based phylograms (with the exception of that derived from the glycosyl hydrolase), as well as the concatenated gene-based tree, LpTG-2 GC2 was more closely related to E. typhina E8 (strain ATCC_200736) and E. typhina 9636 than the two other E. typhina strains, 9340 and E5819. Furthermore, in the tubB- and MEAB protein-specific phylograms, GC2 of LpTG-2 strain NEA4 was closer to E. typhina E8, while that of NEA11 was closer to E. typhina 9636. In contrast, in the DEAD box-based phylogram, NEA11 GC2 was closer to E. typhina E8, while NEA4 GC2 was closer to E. typhina 9636.

Identification and phylogenetic characterisation of MT genes

Comparison between the genomic sequences of perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference gene sequences corresponding to the MT idiomorphs, MTA (mtaA, mtaB, mtaC) and MTB (mtbA), revealed the presence of a single idiomorph in all strains. MTB was detected for all E. festucae var. lolii and PNT strains, with the single exception of E1, which possessed all three genes corresponding to mating type idiomorph MTA. Two copies of mtbA were identified for each of the two LpTG-2 strains (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis was performed by comparison of the mtbA gene copies, excluding only strain E1 due to possession of the opposing MT idiomorph. In contrast to the other 6 gene-specific phylograms, the MT gene-specific tree was separated into two major clades, one representing E. festucae var. lolii, LpTG-2 GC1 and PNT, the other representing LpTG-2 GC2 (Additional file 2). The MT sequences of the first clade were similar, and clustered with that of E. festucae Fl1, while those of the second clade were also similar, and showed affinity, albeit at a lower level, to those of several strains of E. typhina.

Phylogenetic characterisation based on concatenated gene sequences

All gene sequences, apart from those of the MT genes (due to presence of opposite MT idiomorph in E1) were concatenated and analysed by ML and NJ methods, providing strong bootstrap support for all major clades that were defined by single gene-based phylogenetic analysis (Figure 7). In this phylogram, E. festucae Fl1 clustered with E. festucae var. lolii, and E. festucae 2368 clustered with PNT. However, when the perA sequences were removed from the concatenated gene structure, both E. festucae Fl1 and E. festucae E2368 clustered preferentially with PNT (Additional file 3), suggesting a predominant influence of perA in the analysis, possibly due to the large length of this gene in comparison to the others (Table 3).

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of concatenated gene sequences of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Discussion

Phylogenetics of previously characterised endophyte taxa

In the present study, sequence diversity of multiple independently selected genes was used to identify the phylogenetic affinities between perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes, and to interpret potential progenitor relationships with contemporary sexual Epichloë species. This study represents the first use of whole genome data to obtain full-length sequence of multiple genes for phylogenetic analysis of perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes. The results revealed the existence of three major groups, confirming relationships previously deduced from SSR-based genotyping, of which two (corresponding to E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2) have been previously described. Limited sequence diversity for all selected genes was detected within each taxon, as would be expected for asexual species [46]. In contrast, the multiple isolates of the sexual species E. typhina displayed higher levels of variation, as is further supported by possession of different MT genes and substantial differences between mitochondrial genomes [24,30].

The identities of progenitors for E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2 have been identified in several previous phylogenetic studies. The most common endophyte of perennial ryegrass, E. festucae var. lolii, has been proposed as a direct haploid descendant of E. festucae, while the heteroploid LpTG-2 was suggested to have evolved through hybridisation of E. festucae var. lolii and E. typhina [24,47]. Equivalent phylogenetic affinities were observed in the current study. Of the two reference E. festucae strains that were used, Fl1 appears to be more closely related to E. festucae var. lolii strains based on the tubB- and perA-specific phylograms, while both strains exhibited similar levels of affinity to E. festucae var. lolii in the tefA-derived tree.

The origin of heteroploid endophytes may be verified by comparison with multiple candidate progenitor species [48]. E. typhina E8, which was isolated from perennial ryegrass, provided the closest match to LpTG-2 GC2 in the phylograms based on both individual and concatenated gene sequence, consistent with a previous study [24]. The higher variability of GC2 as compared to GC1 may provide evidence for the contributions of different E. typhina lineages to the origin of LpTG-2 strains, rather than a monophyletic event. Further evidence for complexity in the evolution of LpTG-2 is apparent from the MT gene-based analysis. Of the E. typhina strains that were subjected to analysis, E. typhina 9340 and E. typhina MAFF (AB161000.1) display the MTB idiomorph, while the opposing (MTA) mating type was observed in E. typhina E8. Hence, despite the close relationships between E. typhina E8 and LpTG-2 GC2 revealed by analysis based on other nuclear genes, a lineage similar to, but distinct from E. typhina E8 must have been the direct ancestor of the LpTG-2 strains included in the present study.

Phylogenetic identities of PNT genotypes

Similar patterns of relationships between the three distinct clades were apparent for all independently selected gene sequences, apart from the MT genes. The PNT individuals were separated from the other two taxa with strong bootstrap support in all phylograms that included sexual Epichloë reference isolates, except for the moderate value obtained for the tubB-based tree. A similar difference between confidence of structure obtained with individual genes was also observed during phylogenetic analysis of annual ryegrass-derived endophytes based on tubB and nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (rDNA-ITS) sequences. In this analysis, many branches of the rDNA-ITS-based phylogram displayed a lower bootstrap support than the tubB-based phylogram. The discrepancy was interpreted in terms of homoplasy effects and/or the lower number of informative characters that are available from rDNA-ITS gene sequence [26]. Similar considerations may apply to the variability of bootstrap support observed in the present study.

Convergence of gene structure between otherwise distantly related genotypes may also apply to the highly conserved tefA gene, and account for the anomalous location of strain E1 in the respective phylogram. Equivalent patterns of relationships have been reported in other phylogenetic analysis studies. For instance, the tefA gene of the meadow fescue-derived endophyte N. uncinatum was most closely related to that of E. bromicola, but the single tubB gene showed a closer relationship to that of E. typhina [48]. To address such discrepancies, the concatenation approach has been developed in order to obtain more accurate phylogenetic results [49]. Interestingly, the concatenated sequence-based phylograms in the present study displayed strong bootstrap support for the presence of a third taxon grouping, providing additional confidence in the inferences from individual gene sequence analysis.

As for E. festucae var. lolii, PNT strains exhibit the closest relationships to E. festucae among the available contemporary sexual Epichloë species. However, in respect to strain diversity within E. festucae, different relationships were observed across different genes. On the basis of the primary concatenated phylogram, the PNT group showed a closer relationship to E. festucae 2368, while E. festucae var. lolii was grouped with E. festucae Fl1. However, this seems likely to be due to the influence of the perA gene, which contributes a length of c. 7.3 kb that is common to all strains in the study, close to the combined length of the other 5 genes (c. 10.3 kb). In the absence of the perA gene, members of the PNT group seem to exhibit a slightly higher affinity to both E. festucae isolates (Additional file 3), perhaps indicating an origin from a similar progenitor, while E. festucae var. lolii may have arisen from a variant of E. festucae that either has not been included in the analysis, or is not represented in the contemporary range of intraspecific diversity. Nonetheless, the MT gene-based analysis indicates that all E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2 strains display the MTB idiomorph, either in single or double copy number, similar to E. festucae Fl1. It is worthwhile to consider whether the conflicting results may be an artefact of limited sampling of genomic diversity, and a definitive analysis will depend on comparison of whole genome sequences.

Separate taxonomic status for members of the PNT group was also supported by evidence from chemotypic diversity. Metabolic profiling for the presence of known alkaloids revealed that all of the E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2 strains included in the present study produce at least one of the three common compounds, lolitrem B, ergovaline and peramine [50]. However, members of the PNT group have been shown to produce none of these metabolites, but rather to synthesise another class of bioactive metabolites, the epoxy-janthitrems [35,51]. The failure to synthesise peramine is consistent with the 1223 bp 3’-terminal deletion of the perA gene in all individuals, as well as the premature stop codon at coordinate 2923 bp in all but E1, in each case generating a non-functional gene copy. The presence of the majority of the perA gene, however, suggests that PNT endophytes may have possessed an intact perA gene at some stage of evolution, followed by a deletion event similar to that inferred to have occurred in endophyte strains E. typhina E1022 and E. festucae E2368 [28].

Conclusion

Although the endophyte strains located within the PNT group are phylogenetically distinct from both E. festucae var. lolii and LpTG-2, evidence suggests that they may represent not one but two distinct novel taxa. Strains 15310, 15311 and NEA12 show near-identity in all individual gene-based trees, indicating a low level of intra-group diversity, and reflecting a probable recent origin from an E. festucae-like progenitor with a MTB idiomorph. Deletion of the 3’-terminus of perA is diagnostic of this group. For these reasons, it is proposed that such members of the PNT group are now designated as belonging to a new taxon, LpTG-3. In contrast, E1, although a sole representative and obviously closely related to LpTG-3, shows unique features, not least the premature stop codon that is additional to the deletion in the perA gene, and most significantly, a MTA idiomorph. On the latter basis, a common origin with LpTG-3 followed by divergence of asexual lineages is difficult to defend. In contrast, a more parsimonious explanation may involve the origin of both types from different genotypes (with contrasting MT idiomorphs) of an E. festucae-like progenitor which had already undergone the perA deletion, leading to establishment of two parallel lineages of asexual endophyte, further modification of perA being confined to the LpTG-3 genomes. Consequently, it is further proposed that although E1 did not originate from a perennial ryegrass host, it is provisionally assigned (pending further investigation) to a fourth taxonomic grouping of perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes as a sister group to LpTG-3, to be designated LpTG-4. As both of the proposed new taxa are capable of producing the novel alkaloid class of epoxy-janthitrems, which display valuable feeding deterrence effects toward invertebrate herbivores, the definition of genomic properties of such taxa is capable of assisting future targeted endophyte discovery programs.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files. All gene sequences have been deposited in GenBank and sequence alignments are availabe in the TreeBASE repository (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S17154) [52]. Details of GenBank accession numbers are provided for each gene-by-isolate combination in tabular form in Additional file 4.

Abbreviations

- BLAST:

-

Basic local alignment search tool

- LpTG:

-

Lolium perenne taxonomic group

- LT:

-

Low-throughput

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- MT :

-

Mating type

- NCBI:

-

National Centre for Biotechnology Information

- NJ:

-

Neighbour joining

- PNT:

-

Putative novel taxon

- SSR:

-

Simple sequence repeat

References

van Zijll de Jong E, Guthridge KM, Spangenberg GC, Forster JW. Sequence analysis of SSR-flanking regions identifies genome affinities between pasture grass fungal endophyte taxa. International Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2011: Article ID 921312, 11 pages, doi:10.4061/2011/921312.

Khan A, Bassett S, Voisey C, Gaborit C, Johnson L, Christensen M, et al. Gene expression profiling of the endophytic fungus Neotyphodium lolii in association with its host plant perennial ryegrass. Australas Plant Pathol. 2010;39(5):467–76.

Cunningham PJ, Blumenthal MJ, Anderson MW, Prakash KS, Leonforte A. Perennial ryegrass improvement in Australia. New Zealand J Agric Res. 1994;37(3):295–310.

Sampoux JP, Baudouin P, Bayle B, Béguier V, Bourdon P, Chosson JF, et al. Breeding perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) for turf usage: an assessment of genetic improvements in cultivars released in Europe, 1974–2004. Grass and Forage Sci. 2013;68(1):33–48.

Posselt UK, Barre P, Brazauska G, Turner LB. Comparative analysis of genetic similarity between perennial ryegrass genotypes investigated with AFLPs, ISSRs, RAPDs and SSRs. Czech J Genet Plant Breeding. 2006;42(3):87–94.

Card SD, Rolston MP, Lloyd-West C, Hume DE. Novel perennial ryegrass-Neotyphodium endophyte associations: relationships between seed weight, seedling vigour and endophyte presence. Symbiosis. 2014;62(1):51–62.

Felitti S, Shields K, Ramsperger M, Tian P, Sawbridge T, Webster T, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Neotyphodium and Epichloë grass endophytes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43(7):465–75.

Leuchtmann A, Bacon CW, Schardl CL, White JJF, Tadych M. Nomenclatural realignment of Neotyphodium species with genus Epichloë. Mycologia. 2014;106(2):202–15.

Rodriguez RJ, White Jr JF, Arnold AE SRR. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytologist. 2009;182(2):314–30.

Schardl CL, Young CA, Faulkner JR, Florea S, Pan J. Chemotypic diversity of Epichloë, fungal symbionts of grasses. Fungal Ecol. 2012;5(3):331–44.

van Zijll de Jong E, Dobrowolski MP, Sandford A, Smith KF, Willocks MJ, Spangenberg GC, et al. Detection and characterisation of novel fungal endophyte genotypic variation in cultivars of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Aust J Agr Res. 2008;59(3):214–21.

Yan K, Yanling J, Kunran Z, Hui W, Huimin M, Zhiwei W. A new Epichloë species with interspecific hybrid origins from Poa pratensis ssp. pratensis in Liyang, China. Mycologia. 2011;103(6):1341–50.

Siegel MR, Latch GCM, Johnson MC. Fungal endophytes of grasses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1987;25:293–315.

Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Spiering MJ. Symbioses of grasses with seedborne fungal endophytes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:315–40.

Ravel C, Courty C, Coudret A, Charmet G. Beneficial effects of Neotyphodium lolii on the growth and the water status in perennial ryegrass cultivated under nitrogen deficiency or drought stress. Agronomie. 1997;17(3):173–81.

Malinowski DP, Belesky DP. Tall fescue aluminum tolerance is affected by Neotyphodium coenophialum endophyte. J Plant Nutr. 1999;22(8):1335–49.

Rowan DD, Gaynor DL. Isolation of feeding deterrents against Argentine stem weevil from ryegrass infected with the endophyte Acremonium loliae. J Chem Ecol. 1986;12(3):647–58.

Wilkinson HH, Siegel MR, Blankenship JD, Mallory AC, Bush LP, Schardl CL. Contribution of fungal loline alkaloids to protection from aphids in a grass-endophyte mutualism. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2000;13(10):1027–33.

Yates SG, Plattner RD, Garner GB. Detection of ergopeptine alkaloids in endophyte infected, toxic Ky-31 tall fescue by mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 1985;33:719–22.

Scott B, Schardl CL. Fungal symbionts of grasses: evolutionary insights and agricultural potential. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1(5):196–200.

West CP. Physiology and drought tolerance of endophyte-infected grasses. In: Bacon CW, White JF, editors. Biotechnology of endophytic fungi of grasses. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994. p. 87–99.

Latch GCM, Christensen MJ, Samuels GJ. Five endophytes of Lolium and Festuca in New Zealand. Mycotaxon. 1984;20:535–50.

Christensen MJ, Leuchtmann A, Rowan DD, Tapper BA. Taxonomy of Acremonium endophytes of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), meadow fescue (F. pratensis) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Mycol Res. 1993;97(9):1083–92.

Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Tsai HF, Collett MA, Watt DM, Scott DB. Origin of a fungal symbiont of perennial ryegrass by interspecific hybridization of a mutualist with the ryegrass choke pathogen, Epichloë typhina. Genetics. 1994;136(4):1307–17.

Moon CD, Guillaumin J, Ravel C, Li C, Craven KD, Schardl CL. New Neotyphodium endophyte species from the grass tribes Stipeae and Meliceae. Mycologia. 2007;99(6):895–905.

Moon CD, Scott B, Schardl CL, Christensen MJ. The evolutionary origins of Epichloë endophytes from annual ryegrasses. Mycologia. 2000;92(6):1103–18.

Tsai HF, Liu JS, Staben C, Christensen MJ, Latch GC, Siegel MR, et al. Evolutionary diversification of fungal endophytes of tall fescue grass by hybridization with Epichloë species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(7):2542–6.

Ghimire SR, Rudgers JA, Charlton ND, Young C, Craven KD. Prevalence of an intraspecific Neotyphodium hybrid in natural populations of stout wood reed (Cinna arundinacea L.) from eastern North America. Mycologia. 2011;103(1):75–84.

Craven KD, Hsiau PTW, Leuchtmann A, Hollin W, Schardl CL. Multigene phylogeny of Epichloe species, fungal symbionts of grasses. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 2001;88(1):14–34.

Ekanayake P, Rabinovich M, Guthridge KM, Spangenberg GC, Forster JW, Sawbridge T. Phylogenomics of fescue grass-derived fungal endophytes based on selected nuclear genes and the mitochondrial gene complement. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13(1):270.

Takach JE, Mittal S, Swoboda GA, Bright SK, Trammell MA, Hopkins AA, et al. Genotypic and chemotypic diversity of Neotyphodium endophytes in tall fescue from Greece. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;78(16):5501–10.

Moon CD, Miles C, Jarlfors U, Schardl CL. The evolutionary origins of three new Neotyphodium endophyte species from grasses indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere. Mycologia. 2002;94(4):694–711.

Moon CD, Tapper BA, Scott B. Identification of Epichloë endophytes in planta by a microsatellite-based PCR fingerprinting assay with automated analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65(3):1268–79.

van Zijll de Jong E, Guthridge KM, Spangenberg GC, Forster JW. Development and characterization of EST-derived simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers for pasture grass endophytes. Genome. 2003;46(2):277–90.

Kaur J, Ekanayake P, Tian P, van Zijll de Jong E, Dobrowolski MP et al. Discovery and characterization of novel asexual Epichloë endophytes from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Crop Pasture Sci., accepted subject to minor revision and resubmitted.

Ekanayake PN, Hand ML, Spangenberg GC, Forster JW, Guthridge KM. Genetic diversity and host specificity of fungal endophyte taxa in fescue pasture grasses. Crop Sci. 2012;52:2243–52.

Rocak S, Linder P. DEAD-box proteins: the driving forces behind RNA metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:232–41.

Palomares-Rius J, Hirooka Y, Tsai I, Masuya H, Hino A, Kanzaki N, et al. Distribution and evolution of glycoside hydrolase family 45 cellulases in nematodes and fungi. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14(1):69.

López-Berges MS, Rispail N, Prados-Rosales RC, Pietro AD. A nitrogen response pathway regulates virulence in plant pathogenic fungi. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5(12):1623–5.

van Zijll de Jong E, Dobrowolski MP, Bannan NR, Stewart AV, Smith KF, Spangenberg GC, et al. Global genetic diversity of the perennial ryegrass fungal endophyte Neotyphodium lolii. Crop Sci. 2008;48:1487–501.

Davidson SE, Sawbridge TI, Rabinovich M, Kaur J, Forster JW, Guthridge KM et al. Pan-Genome analysis of perennial ryegrass endophytes. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on the Molecular Breeding of Forage and Turf 2012’ Salt Lake City, UT (Eds BS Bushman, GC Spangenberg) p 80 (MBFT Organizing Committee) 2012.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang JH, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST - A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–402.

Schardl CL, Young CA, Hesse U, Amyotte SG, Andreeva K, Calie PJ, et al. Plant-Symbiotic Fungi as Chemical Engineers: Multi-Genome Analysis of the Clavicipitaceae Reveals Dynamics of Alkaloid Loci. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003323.

Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18(5):821–9.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9.

Clay K, Schardl S. Evolutionary origins and ecological consequences of endophyte symbiosis with grasses. Am Nat. 2002;160:S99–127.

Craven KD, Blankenship JD, Leuchtmann A, Hignight K, Schardl CL. Hybrid fungal endophytes symbiotic with the grass Lolium pratense. Sydowia. 2001;53(1):44–73.

Schardl CL. The Epichloë, symbionts of the grass subfamily Poöideae. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 2010;97(4):646–65.

Gadagkar SR, Rosenberg MS, Kumar S. Inferring species phylogenies from multiple genes: concatenated sequence tree versus consensus gene tree. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2005;304B(1):64–74.

Tian P, Kaur J, Guthridge KM, Rochfort S, Forster JW, Spangenberg GC. Metabolome analysis of symbiota established with novel Neotyphodium endophytes in a diverse panel of isogenic perennial ryegrass host genotypes In: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on the Molecular Breeding of Forage and Turf 2012’ Salt Lake City, UT (Eds BS Bushman, GC Spangenberg) p 112 (MBFT Organizing Committee) 2012

Kaur J, Ekanayake PN, Rabinovich M, Ludlow EJ, Tian P, Rochfort S et al. Analysis of compatibility and stability in designer endophyte-grass associations between perennial ryegrass and Neotyphodium species. In ‘Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on the Molecular Breeding of Forage and Turf 2012’ Salt Lake City, UT (Eds BS Bushman, GC Spangenberg) p 73 (MBFT Organizing Committee) 2012.

Hettiarachchige I, Ekanayake PN, Mann RC, Guthridge KM, Sawbridge TI, Spangenberg GC et al. TreeBASE 2015. http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S17154.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the Victorian Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources, the Molecular Plant Breeding Cooperative Research Centre and the Dairy Futures Cooperative Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IKH performed the gene sequence extraction, phylogenetic analysis and drafted the manuscript. PNE, RCM, TIS, KMG, JWF and GCS co-conceptualised and coordinated the project, contributed to data interpretation and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

De novo assembly statistics for sequenced perennial ryegrass-associated endophyte genomes.

Additional file 2:

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of the MT gene sequence, mtbA , of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes and reference isolates. The GenBank accession numbers of the MT genes derived from ryegrass-associated endophytes are provided in Additional file 4. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Additional file 3:

Phylogram resulting from ML analysis of concatenated gene sequence ( tubB , tefA , DEAD, glycosyl hydrolase and MEAB) of selected perennial ryegrass-associated endophytes. Diagram properties are as described for Figure 1.

Additional file 4:

Genbank accession numbers of the sequences represented in the phylogenetic study.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hettiarachchige, I.K., Ekanayake, P.N., Mann, R.C. et al. Phylogenomics of asexual Epichloë fungal endophytes forming associations with perennial ryegrass. BMC Evol Biol 15, 72 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0349-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0349-6