Abstract

This study examines the impact of the charging of tuition fees between 2006 and 2014 in several German federal states on the number of first-year student enrollments. Since Germany is known for a tuition-free education policy at public institutions, the fundamental question arises of whether, and if so, to what extent, the temporary tuitions influenced the number of first-year-student enrollments. In this regard, Becker’s human capital theory suggests that rising fees should be associated with declining enrollment rates. The analyses to test the hypothesis are based on a longitudinal administrative panel data set for 206 universities and universities of applied sciences from 2003 to 2018; this means there are 3296 observations before, during, and after the tuition treatment. While no previous study has covered the full period of the policy or undertook more aggregate-level analyses, this study applies an analytical research design that uses several panel-data models and robustness checks to examine causal relations based on a quasi-experimental setting. The results of Fixed effects regressions confirm the hypothesized negative impact and even reveal a persistent negative effect of the treatment. The comparison of higher education institutions with and without tuition fees shows that the former institutions lost approximately between 3.8 and 7 percent of their first-year student enrollments on average.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Like many other European countries, Germany has moved towards a system of “mass higher education” in recent decades (Huisman et al. 2000, p. 219; Trow 1972). Higher education (HE) entry rates increased from 9% in the 1960s to 58% in 2014 (Hüther and Krücken 2018, p. 49). In a knowledge intensive society, there are certain advantages of such higher educational expansion: higher education institutions (HEIs) can meet the high demand for skilled workers (Gago et al. 2005; Gillmann 2018; Huisman et al. 2000), offer educational opportunities (Kivinen et al. 2001; Trow 1972) and improve upwards mobility (Autor 2014; Machin and McNally 2007). But this also raises the question of how to finance this expansion, now and in the future. One potential instrument to overcome this problem is “Shifting the Burden” (Heller and Rogers 2006) by requiring students (and their parents) to contribute to paying for higher education (Johnstone 2004)—e.g. via tuition fees—as Germany did between 2006 and 2014. Although a price raise seems appropriate considering the college-wage premium that graduates enjoy (Elliott and Soo 2013), such policies may nevertheless prompt potential students to rethink their decision to attend university. Decreasing enrollment (or application) rates due to potential students’ price responsiveness (Elliott and Soo 2013; Heller 1997; Hemelt and Marcotte 2011; Leslie and Brinkman 1987) may be particularly problematic in Germany given that the country has been a latecomer in terms of tertiary education growth and still lags behind other OECD countries (Hüther and Krücken 2018, p. 50). One reason for these lagging HE enrollment rates has been the vocational training system, which offers an alternative path (Hüther and Krücken 2014) that may attract students from lower socio-economic backgrounds in particular ( Becker and Hecken 2008). Considering the German situation of higher education as a public good (Gayardon 2019), policy adjustments to HEI funding should only be made if unchanging enrollment trends can be assured. Thus, the key question is: To what extent did the imposition of tuition fees lead to changes in the number of students enrolling in Germany? This paper aims to clarify whether an effect existed, how large it was and whether it persists.

After a long period without public tuition fees in Germany,Footnote 1 in 2005 the German Constitutional Court (GCC) ruled that the German federal states have the autonomy to impose tuition fees at their public higher education institutions (HEIs) owing to the German federal states’ competency to regulate education (BvF 1/03 2005). Following this decision, some states imposed such fees, while other states did not. The states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony pioneered this policy in the 2006–2007 winter semester, followed by Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hamburg, Hesse, and Saarland during 2007. In these fee-charging states (FS), students had to pay up to €500Footnote 2 per semester,Footnote 3 while HE attendance was still free of charge in non-fee-charging states (NFS).Footnote 4

Consequently, until 2015, tuition fees in Germany varied by the state and the year in question (see Fig. 1). Analogous to Boix (1997) supply side logic, right-wing states (Christ Democrats and Free Democrats) in particular pursued the introduction of the fees, while the abolition of the fees was mostly achieved by a change of government towards left-wing governments (Social Democrats, Left Party and Green Party) (Kauder and Potrafke 2013; Türkoğlu 2021). Heated political debates and nationwide student protests between 2006 and 2010—especially emphasizing social inequality and equal opportunities—led to the abolition of tuition fees (Heine et al. 2008; Timmermann 2019). Only 1 year after first introducing them, the state of Hesse already stopped imposing tuition fees and in subsequent years, other federal states followed. This led to the complete abolition of tuition fees in all German states—and thus at all public HEIs—by the end of 2014. Generally speaking, seven out of the 16 German federal states imposed tuition fees for at least some time during this period and nine states opted not to do so. Given the largely uniform fees earned by Germanys HEIs and their potential link to declines in student numbers—which are an important measure for HEIs’ indicator-based public funding (see Leszczensky (2004))—an analysis of the German policy may be useful when assessing tuition policies in other countries with federalized education systems and predominantly public tertiary education funding.

Evolution of tuition fee implementation and abolition by federal states in Germany, treatment dates (states in dark grey) have been drawn from Bahrs and Siedler (2018)

There are three key reasons why the German case may be especially useful for understanding student responses to HEI fees: First, the federally varying fees charged between 2006 and 2014 are an exception in Germany, which is otherwise known for its fee-free nature; second, there was a nearly universal treatment across the sample; and third, the quasi-experimental situation allows for the use of various statistical methods of causal analysis.

This paper adds to the existing literature by considering 206 universities and universities of applied sciences (together and in subgroups) using a (balanced) panel data set covering 16 years. Until now, comparable studies have predominantly worked on the degree of study intentions. Only two previous studies estimate the actual impact of tuition fees at the institutional level based on process produced data (Bruckmeier et al. 2013; Mitze et al. 2015). Since in both cases the study period does not exceed the year 2010, so far, no study can determine the effect of tuition fees on the meso level over the entire period and beyond. Moreover, the Fixed-effects regression analysis systematically considers dynamic lead and lag effects, temporary and persistent treatments and a number of covariates which reflect the situation of the educational and economic policy in Germany. Thus, it not only considers anticipation of tuition fees, medium-term adjustments or nonimmediate transition from high school to university, but also the implementation of the Bologna reform in Germany and the situation on the labor and vocational training market.

The remainder of this study proceeds as follows. In the next section, I review the state of research. I then present theoretical reasoning based on Becker’s human capital approach as well as the associated hypotheses. The subsequent section describes the data, operationalization, and estimation strategy. I then present a descriptive analysis of the link between tuition fees and student enrollment. The results section with the panel data regression analyses presents the results of a Fixed-effects regression comparing a temporal and a persistent treatment. A first-difference estimation based on a different slope underscores the robustness of the results. The subsequent chapter presents robustness tests for different subgroups, aggregation levels and observation periods. The paper closes with a short conclusion as well as a discussion of limitations and finally describes avenues for future research.

1.1 State of research

Across the world, tuition fees have prompted controversy on the streets, in the parliaments, and in research. The main issue goes beyond whether or not to attend HE. Fee-paying students do not just need to decide on their educational pathway but also need to find ways to cope with direct and indirect costs. Besides financial support in the family, students may rely on grants and loans (for an overview of tuition-subsidy regimes see Garritzmann (2016)). To access these grants and loans, students face equally controversial borrowing constraints (Johnson 2013; Keane and Wolpin 2001). Further problems arise for those who do not want to or cannot access such programs as well as for those who are not sufficiently supported by them. For example, there is evidence that student employment increases (Neill 2014), with various consequences, including declining academic performance for some subgroups (Kalenkoski and Pabilonia 2010). If students are expected to pay more fees after the extend of a general program`s length, the probability of their late graduation is reduced (Garibaldi et al. 2007). However, given the relevance of tertiary education for economies and individuals, declining intentions to pursue higher education are one of the most devastating consequences and thus also a central field of research and controversy. Many international researchers have noted a reduction in HEI enrollments (or applications) due to the increase or introduction of fees, which largely affect students from low-income families (Coelli 2009; Declercq and Verboven 2015; Elliott and Soo 2013; Neill 2009; Pigini and Staffolani 2016). The results are consistent with those of meta-analytic studies from Leslie and Brinkman (1987), Heller (1997) and Hemelt and Marcotte (2011) for the United States. Others have not found that fees generally negatively affect enrollment (Canton and Jong 2005; Havranek et al. 2018) or change the socio-economic gradients (Denny 2014).

The German case is interesting because the treatment by tuition fees took place almost uniformly across federal states, the treatment also resembled a random assignment and the short treatment duration and availability of process produced administrative data at the HEI level enabled me to compare before, during, and after the intervention. Table 1 summarizes the inferential statistical analyses on the German tuition fee intervention structured by level of aggregation. There are two main research concentrations: individual-level studies using data from the HIS school leavers survey and studies conducted at state- or institutional level using administrative data from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. The obviously different outcomes might be a result of differences in the levels of aggregation, the data sets, observation periods and the methods, as Shin and Milton (2008) have noted for research on the United States. For instance, Bruckmeier and Wigger (2014) did not find a significant effect using state-level data, but Bruckmeier et al. (2013) found an effect using HEI-level data. In addition, the existing research for Germany was mostly conducted immediately after tuition fees were introduced and no studies have looked at the period after tuition fees were abolished. The results of the individual-level studies (Bahrs and Siedler 2018; Baier and Helbig 2014; Dietrich and Gerner 2012; Heine et al. 2008; Heine 2012; Helbig et al. 2012) vary but show that tuition fees tended to have a negative effect on higher education enrollment. The same applies for the more aggregated state-level studies. Of all the published studies using this approach, only Hübner (2012) found a negative effect that was statistically significant. An only slightly smaller effect is reported by Bietenbeck et al. (2022) in a recent discussion paper, but the study period also extends just to 2010. The two studies using institutional-level data did find significant negative effects—Bruckmeier et al. (2013) and Mitze et al. (2015)—but the results of the latter study were not robust for all subgroups. None of these studies covered the full tuition-fee period in Germany, so they largely just detected effects shortly after the introduction of fees. Given the importance of tuition-fee policies worldwide and the benefits of researching the German setting, which resembles a quasi- experiment in a federalist system, the present study can help to explain young adults’ responses to tuition-fee changes. The analytical research design deployed in this study allows me to analyze a comprehensive and administrative panel dataset on the disaggregate HEI level with data beyond 2012 addressing the temporal and persistent effect of tuition fee treatments on first-year enrollments via static and dynamic approaches.

1.2 Theory

My study uses Becker’s (1993) theoretical behavior model to explain the enrollment choices of German high-school graduates on the micro level. According to Becker, individuals conduct cost–benefit analyses between several educational options when considering how to maximize the net utility of a personal investment (e.g., in their own education, health, or training). In my study, enrollment decisions are seen as an investment: If the benefits of getting a tertiary degree (weighted by the probability of success) are higher than the associated costs, they will enroll. The costs of HE attendance consist in the (indirect) opportunity costs of forgone wages for a job that only requires a skilled-worker qualification and the direct costs of studying due to tuition fees, administration fees, accommodation costs, and so on. The benefits are the higher future earnings for degree holders (the so-called “higher-education premium”)—justified by productivity increases—or higher social esteem. Ceteris paribus, tuition-fee introduction increases direct costs by about €1,000 per year while future benefits remain constant. This means that introducing tuition fees should decrease the net utility of university attendance. Thus, the number of enrollments should decrease.

Hypothesis 1

Tuition fees have a negative impact on the number of first-year students enrolling in fee-charging HEIs.

Becker’s model also enables me to consider the formation of rational expectations (Becker and Mulligan 1997). If students in secondary education already anticipate rising costs based on current policies and discussions, this should lead to a decline in present enrollments due to a projected cost–benefit analysis. This anticipation effect may also be explained by a lack of patience among individuals who prefer the present financial security (and extended working life) that comes with choosing vocational training over the uncertain fee situation in higher education. Even though the first serious proposals were presented by the German Rectors’ Conference in 2004 (Hüther and Krücken 2014), students could only expect the introduction of fees in their specific federal state after the ruling of the GCC in 2005. Thus, this anticipation period should be limited to two years.

Hypothesis 2

The anticipation of tuition fees has a negative impact on the number of first-year students enrolling in fee-charging HEIs, even before their official introduction.

Are these hypotheses the only ones that could be derived from the model? One argument put forward is that the benefit of a university degree is much higher than the perceived small rise in costs. Yet this argument fails to consider the existence of a group of students who only marginally decided to enroll in university, even before the introduction of tuition fees. So, at the margin, tuition fees should be associated with a decreasing number of enrollments. Nevertheless, this impact could be limited to a small number of (possible) enrollments at HEIs. To detect this (likely small) effect, a large data set—such as the present one—is necessary.

A more substantive argument relates to policymakers’ aims in introducing tuition fees, which concerned improving the quality of education at German universities. These improvements could have led to increased expectations of a) success and b) future employability (Bates and Kaye 2014). Rational calculations of costs and benefits involve weighing these perceived quality improvements against their costs. Thus, the negative effects of increased costs and the positive effects of increased educational quality could have cancelled each other out. But, both the signaling effect on potential students and the students' perception of an increase in quality during this period have been empirically contradicted so far. On the one hand, a study by the German Parliament (2009) came to the conclusion of general student dissatisfaction with the fees, attributing this in particular to the lack of belief in quality improvements surveyed in the so called “Gebührenkompass” (cited in German Parliament (2009)). At the same time, the results of Heine et al. (2008) showed that for about one third of the students a quality expectation of the fees can be shown. There is a discrepancy here between expectation and actual satisfaction with the policy. On the other hand, the latter study also showed that only 2% of eligible students in 2006 believed that a university with tuition fees would provide a better education. In addition, from 2003 onward, the protest movement against the marketization of education formed (Türkoğlu 2021), in which school children played a major role and whose claims included "free education for all" (Bundesweiter Bildungsstreik 2009). The above-mentioned studies thus suggest a deterioration in quality expectations over time rather than an improvement. Consequently, both the anticipation of the fees and their subsequent introduction must be based on the assumption that the costs outweigh the benefits created.

Furthermore, looking at the German labor market over the last 30 years, there is a clear trend towards a growing number of high-skilled jobs. This means that the benefits of tertiary education in terms of finding well-paid employment have increased. These considerations should have led to a growing share of high-school graduates enrolling at universities, which could have counteracted the declining student numbers through tuition fees. The negative influence of tuition fees might thus have been outweighed by this general positive trend.

Hypothesis 3

The number of high-school graduates has a positive impact on the number of first-year students.

To test these hypotheses, it is necessary to analyze a long panel data set. This is what the following sections are doing.

1.3 Data and variables

The present analysis primarily uses process produced administrative data on the disaggregated level of HEIs for the winter semesters 2003–2004 to 2018–2019 (Federal Statistical Office of Germany 2020a, b). My dependent variable is the number (count) of first-year students from GermanyFootnote 5—I use both the total number and the number for particular subgroups in robustness checks. All models are based on a log-linear specification of my dependent variable. The mean number of first-year students per institution is 1,231, the deviations are due to institutions of different sizes as well as higher variation within the observed units. After data cleaning, data for 206 HEIsFootnote 6 on enrollment after interstate migration were available.Footnote 7 This generated a data set that was comprehensive in scope (institutions) and scale (years) and that contained 3,296 HEI-year observations in total. I had information on whether a given state implemented tuition fees—independent variable—in a specific year (Bahrs and Siedler 2018; Mitze et al. 2015) and included this as a dichotomous treatment dummy which is additionally tested for dynamic effects of anticipation. The treatment applies to 22% of all observations in the sample. Alternative specifications use a persistent treatment on state level after a first treatment to check medium-term effects. The descriptive statistics of the main variables in my full sample are listed in Table 2, group wise summary statistics can be found in the supplements.

The data set includes the number of high-school graduates [in thousands] by state to control for the potential number of students (Federal Statistical Office of Germany 2020a). The reasons for this are twofold. First, this variable controls for changes due to the reform of the German high-school system (G8-reform) in some states between 2007 and 2013, which reduced the number of years German students spent in high school. Thus, the relatively high range is attributable to exceptionally large numbers of high-school graduates in some states and specific years. Furthermore, single city-states as Bremen generally have fewer students. Second, it controls for the sharp decline in birth rates in the eastern states of Germany after reunification from 1991 to 1995 (The World Bank Group 2020) on the one hand and the strong increase towards higher educational qualifications on the other. To capture the reforms of the higher education system to the bachelor and master system, I control for the share of these degree forms within all intended degrees (Federal Statistical Office of Germany, personal communication, September 7, 2021). Their average varies between 5% in 2003 and 76% in 2018. Based on past evidence (Casillas 2010; Dayhoff 1991; Hsing and Chang 1996) I control for unemployment effects (Federal Employment Agency 2021) and economic wealth (GDP at current prices per employed person by Federal and State Statistical Offices (2022)) on state level.

Beyond the covariates displayed in the summary statistics, I use a number of lead and lag variables as well as first differences and trend specifications. The analysis further entails various robustness checks to control the results on a subgroup level (see “Robustness Checks” section below).

1.4 Identification strategy

My identification strategy is based on the assumption that the introduction and abolition of tuition fees represented a quasi-experimental randomization in the sense of a "government randomization" (Meyer 1995, p. 151; Wooldridge 2012, p. 457). The underlying premise is the federal autonomy of the states in Germany, which, according to the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court, also applies to the charging of fees. Neither the institutions, nor the potential students, nor I as a researcher had any influence on the following non-uniform imposition—the treatment assumed here—of the fees. In addition, visual (plotting of group means over time and visual inspection of subsets) and statistical (tests on the interaction of group-specific linear time trends as well as extended dynamic model specifications) inspections did not provide a priori evidence of subgroup heterogeneity among school graduates and students before the assignment of the treatment that would argue against a common trend (Angrist and Pischke 2009, p. 239). Further events that occurred during this period were discussed by Alecke et al. (2013) and Hübner (2012). For the most part, these events were consistent with the common trend assumption. Nevertheless, students may have substituted fee-charging HEIs for non-fee-charging HEIs in the years when tuition fees were imposed. The results must be interpreted with this possibility in mind. All in all, the treatment (tuition fees) and nontreatment (lack of tuition fees) arguably resembled a random assignment.

In order to account for heterogeneity across institutions, e.g. due to different sizes or strategic orientations (Baltagi 2013), as well as for group-specific selection effects across federal states, I test my assumptions on the basis of panel data regressions with fixed effects. This has been chosen after the Hausman test refuted the null hypothesis of no differences between the FE approach and the alternative random effects (RE) method Thus, my specification does allow for averaging out all unobserved heterogeneity by within transformation. Time-specific influences are controlled by a federal-state-specific trend interaction. This approach considers a general time trend and allows for variation between the states (e.g. a varying trend towards higher-education enrollment)).Footnote 8

My dependent variable is the logarithmized number of enrollments at each institution and the time intervals between the measurements are identical. Marginal changes of the predictors by one unit can be interpreted as a percentage change of student enrollments. Furthermore, I included leads of the tuition-fee variable and lags of the high-school-graduates variable. The theoretical reasoning supported the inclusion of lead effects to model for the anticipation of tuition-fee implementation and abolition (Ashenfelter 1978). I inserted leads of one and two years. Furthermore, there were several reasons why high-school graduates might not have enrolled at a HEI in the year of their graduation. First, until 2011, males had to complete military service for a mandatory 12-month period. Second, many graduates decided to complete an internship, volunteer, or participate in a work-and-travel program before starting higher education. Thus, the dynamic approach included lags in the number of high-school graduates for one and two years.

To examine whether the effect of tuition fees is temporary, short-term, or persistent, I then vary the treatment variable. To do so, I first apply a first-differences approach. As in the previous fixed effects approach, the first-differences approach also averages out time-invariant heterogeneity across institutions (Greene 2018). For my data with t > 2, I expected that the results would not be identical to those found with the aforementioned approach and would not be unbiased (Wooldridge 2012, p. 490). Second, I use a treatment variable that continues the treatment even after the abolition of fees in the respective state. If tuition fees have not only temporarily but also sustainably reduced the number of students, this can be assessed in the context of this modeling.

For all models I use cluster robust standard errors for identification after testing group wise heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation with a modified Wald test to check the first, and a Wooldridge test to check for the latter (comparisons with bootstrapped SE´s show similar results). After the literature review of previous studies revealed varying results of aggregated and non-aggregated data as well as for different subgroups, I introduced additional models to examine the effects on the more aggregated federal state level, by gender and institutional type.

Since the visual inspection of enrollments (see chapter below) already show strong variations, it cannot be ruled out that individual states in the treatment or non-treatment group dominate the effect of tuition fees. To check the robustness of the overall effect, I sequentially leave out individual states from my calculation and check the effects in the reduced sample (leave-one-out test).

To test the above-stated hypotheses, these models were estimated on a comprehensive panel dataset of 3,296 observations that could detect even small variations in the number of first-year students caused by the imposition of fees and other exogenous variables.

1.5 Empirical evidence

1.5.1 Descriptive statistics

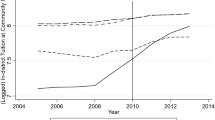

To illustrate the overall developments, I first conducted descriptive analyses of the panel dataset. These analyses underline the necessity of the subsequent models. Figure 2 depicts the total enrollments of first-year students in FS and NFS throughout the entire period. Two points are immediately evident: First, there was a generally positive trend towards enrollment in public higher education. However, this trend was interrupted at the beginning of my observation period. Second, there was a sudden rise in enrollments in 2011.Various explanations are plausible. For example, anticipatory effects may have led to decreasing enrollments, since they increased prior to the period under review. However, the reorganization of the German high-school system after 2007 in 12 of the 16 German states triggered a steep rise in the number of high-school graduates in some years and may therefore have caused a rising number of enrollments as well.

A possible drawback of this general analysis is that it obscures the potentially very different development paths in FS and NFS. Therefore, in the next step, I divide the data into subgroups to differentiate the impact of tuition fees on the treatment and the control group. FS include all states that imposed tuition fees between 2006 and 2014. Different development paths in both subgroups are presented as percentage changes (Fig. 3) compared to the year before.

From 2005–2006 to 2013–2014, both groups diverged. Despite the tuition fee charging, the FS continue to record a positive trend in up to 2010. This can also be seen for the NFS. However, their growth exceeds that of the treatment countries from 2008 onwards, until a sudden sharp increase in 2011. At that time, three federal states had already abolished the fees again. After the abolition in 2014, the developments proceed in a common path again. A variety of factors may explain the growth even after the introduction of fees. For one, high-school graduates may have already accepted paying tuition fees within their states. Another possibility is that the rise in the number of enrolled students in FS could be attributed to the exceptionally high numbers of high-school graduates in single years.

Summing up, the descriptive analyses suggest that different forces are at hand, both at the level of groups and regarding the 16-year study period. The resulting complexity—which was especially evident in the tuition-fee period between 2006 and 2014—requires a multiple panel regression analysis.

1.5.2 Panel data regression analysis

Table 3 below shows the results of my main specification with the logarithmized enrollment number as dependent variable. The entire sample is estimated over the full period (minus the time-leaded and -lagged observations due to the dynamic specification in the full model). All following models—beside specific comparisons in the robustness section—control for the number of secondary school graduates, the unemployment rate in the respective state as well as the vocational training contracts concluded there, the gross domestic product on federal state level per employed person and the share of intended degrees that are already in the bachelor- and master-mode. While institutions in FS are the treatment group, those in NFS are the reference group. To compare the robustness of different specifications, I build my central model (4) in a stepwise approach. Model (1) only considers the treatment effect and the variation of the graduates. It already shows a negative treatment effect and takes fixed effects at the institutional level into account. Extending the model with economic influences, vocational alternatives and taking the Bologna reforms into account shows positive effects of the latter covariates on the number of enrollments in model, while the first show a negative influence (2). Trends and dynamic effects are considered in models (3) and (4). Since the vocational training contracts are an alternative to higher education, the positive influence in model (3) is implausible. However, this effect disappears when the federal-state-specific time trends are considered in the subsequent model. Adding these improves the overall model fit slightly, the treatment effect remains robust. The results of the central model (4) considering dynamic effects of the treatment and school graduates show that institutions that received the treatment have a significantly lower number of enrollments—by about 6,95 percent less—, if all other factors are held constant.

Examining the lead effects of the treatment, no anticipation of charges can be identified. The effects of one- and two-year leads vary in direction (correlation between the lead effects is relatively low at 0.1278), but neither is significant. Furthermore, the high-school-graduate variable indicates that the number of high-school graduates has a positive and significant impact on the number of enrollments. This applies over and above the positive immediate impact and captures one of the assumed lags. Table 4 below compares the results of another specification, based on a persistent treatment, with a first-differences specification.

The specification based on a persistent treatment estimates a significant decrease in students by 8.14 percent. The effects of the other variables are analogous to the previous specification, but under these assumptions a significant anticipation effect of 2.85 percent less enrollment is apparent, while the two-year lead has a negative sign as well. Assuming that the effect of tuition fees persists beyond the actual treatment, it is somewhat stronger than under the assumption of a temporary treatment. The following first-differences approach cancels out all time-invariant heterogeneity between the institutions. In particular, the first differences estimation considers the slope based on the values immediately before the onset of the treatment and is thus more inefficient than the alternative chosen specification, when the time series is larger than two periods. Despite this limitation, institutions that received treatment had a decrease in the number by 7.78 percent, ceteris paribus. Thus, the coefficient is again slightly higher than in the main specification and even here significant, confirming the robustness of the main model results.

My main interest was in analyzing the effect of tuition-fee introduction on the number of enrolled students. Three dynamic panel data models specified various timing of this effect and found this effect to be significant and negative temporarily and even persisting after the abolishment of tuition fees in Germany. The effects went in the hypothesized direction based on human capital theory, meaning that German students are sensitive to cost increases and HEIs that imposed fees lost students. Respectively, states that have implemented this policy have—at least in the duration of the observation period—sustainably lower enrollments. An anticipation effect, which was modelled by the two leads, did just occur in the long-term specification and for just one year. Regarding the contradictory effect of a general trend towards higher education, both the descriptive analyses and the regression analyses supported my previous assumptions. Thus, the number of university entrance qualification holders had the expected positive effect on the number of first-year students.

1.6 Robustness checks

As the data included several selective subgroups, robustness checks were necessary. While detailed outcomes can be found in the appendix, group wise summary statistics are attached to the Additional file 1.

First, I examined my main specification separately for universities and universities of applied sciences. By doing so, it becomes apparent that the negative effect is present for both subgroups, but is somewhat smaller for the classic universities (see Appendix 1). Moreover, the labor market influences only affect enrollments at universities of applied sciences significantly, while the lag effect of secondary school graduates, which can be seen in the overall model, only occurs at classic universities. This induces a more direct transition into higher education for students opting for the applied sciences institutions.

Second, I examined models separately by gender (based on the same institutional sampling). Although female participation in HE has been rising and is about to surpass male tertiary participation in many fields (Buchmann et al. 2008; Schofer and Meyer 2005), there are still some differences between the subgroups of students. Costs-benefit analyses for education vary by gender. According to Lörz et al. (2011), female students also evaluate HE benefits smaller than their male counterparts. Based on these findings, human capital evaluations should lead to greater decreases in the subgroup of female first year students. Appendix 2 shows the results that confirm this assumption. While the group of women records a decrease of about 8.72 percent, the group of men loses on average only 5.78 percent of the enrollments. The associations of a positive influence of secondary school graduates applies to both genders equally, while just for male students a significant lag effect can be observed one year after treatment. Subsequently, women are more sensitive to the fee charges.

Third, to compare my results with previous studies with similar modeling but different aggregation level or shorter observation period (Bruckmeier et al. 2013; Bruckmeier and Wigger 2014; Hübner 2012), I aggregated my dataset and estimate results both at the state level and in a disaggregated setting based on a shorter time series. The former approach is intended to test whether the estimates at the aggregate level are subject to an ecological fallacy. The results—plotted in Appendix 3—are consistent with the findings of the general models and significant. The decrease of 5.47 percent is somewhat smaller than at the disaggregated level.

Furthermore, I restricted the disaggregated dataset to a few control variables and formed three subsamples with different study periods, which correspond to some previous studies. The results can be found in Appendix 4. There, one can see that the negative effect of tuition is robust across all study periods, but has a smaller effect in the shortest study period ending in 2008.

Finally, the figures above have made it clear that enrollment numbers are subject to large variations over the period of the intervention. Thus, in a final step, I re-estimate my central model and sequentially leave out one state at a time to prevent outliers from biasing the effect of my calculations. I have visualized the coefficients of the treatment dummy of the resulting 16 estimates in Appendix 5. When North Rhine-Westphalia is excluded from the sample, the largely stable effect of about 7 percent drops down to an effect of 3.8 percent reduction in enrollments. But, even without North Rhine-Westphalia, the effect remains different from zero and significant at the 0.01 percent level. In the data set, North Rhine-Westphalia dominates in terms of the number of sampled institutions of higher education, and a visual inspection of the data reveals a distinct maximum in the number of graduates and enrollments in 2013. This may be attributable to a simultaneous policy of shortening the high school career path, which may have subsequently influenced the within-difference in my specification, while and shortly after the abolishment of tuition fees. To control for this policy, I calculated a specification with an additional dummy variable that includes so-called "double cohorts" (two graduating classes were merged into one graduating cohort; see Additional file 1: Table S4). However, the double cohorts do not exert a significant effect, and the tuition effect remains at about 7 percent (another model with a one-year lagged effect of the policy similarly provides no further explanatory contribution). An even slightly higher treatment effect is found when leaving out Bavaria. All in all, this test underscores the robustness of the results, but it calls for caution regarding the size of the effect.

The evidence shown here illustrates that the imposition of tuition leads to a reduction in enrollment regardless of gender, type of institution, or observation period aggregation level of the study and drawn subsamples, although different subgroups vary in their sensitivity.

2 Conclusion, limitations, and remarks for future research

I examined a negative effect of tuition-fee imposition in Germany between 2006 and 2014 on enrollment numbers in fee-charging institutions by performing panel data regression with a balanced and comprehensive panel data set. To the best of my knowledge, this study is the first to look at the whole treatment period of the German tuition-fee policy intervention and beyond. My results show a significant decline in first-year student enrollments in German HEIs across all models and support the hypotheses based on human capital theory. Analyses using different regression methods and varying specifications confirm Hypothesis 1. Thus, tuition fees negatively influenced the number of first-year students at a fee-charging institution by about 3.8 to 7 percent less enrollments, confirming the theoretical assumptions. The effect thus adds to the evidence of negative effects of tuition on actual enrollments in the German public system.

Nevertheless, there is a question of why researchers have found very different results regarding the influence of tuition fees when using very similar data sets and regression methods (see Bruckmeier et al. (2013), Bruckmeier et al. (2015), Mitze et al. (2015)). One explanation relates to a variation in the aggregation level and the observation period of studies beforehand. Different explanations were investigated in robustness tests. While generally a higher aggregation level (as in Hübner 2012, Bruckmeier Wigger 2014) shows the same effect direction like results at the institutional level, a shorter study period might contribute to a smaller effect, which becomes largest when measuring the full period between 2003 and 2018. Varying the specification and the treatment from temporary to persistent shows a decrease in enrollments likewise. Thus, tuition fees have not only led to a temporary decrease in enrollment, but also to a sustained reduction (within the period under consideration) at the institutions that charged them. Although it cannot be ruled out that such a general reduction over such a long treatment period is also due to other factors of unobserved heterogeneity, this can be understood as first evidence that even small price increases affect the demand for higher education in a certain region negatively. In addition to the consequences for the reputation of decision-makers by protests in political controversy, this shows in particular that tuition fees should not be considered as a temporary policy instrument.

I did not find general anticipation effects of the introduction of tuition fees, meaning that Hypothesis 2 must be rejected. One explanation for this finding may relate to the ever-changing political debate on tuition fees after 2005 in Germany.

Hypothesis 3 was confirmed as the growing number of high-school graduates increased the number of first year students—but only to a moderate extent. This too, supports the analysis of Bruckmeier and Wigger (2014), which contends that neglecting the number of high-school graduates leads to serious omitted variable bias. As shown by the results of the dynamic specification, there is a one-year-lag effect of school graduates transitioning to higher education.

The significant and negative effect of tuition fees varied by institutional type and the negative effect was stronger for Universities of Applied Sciences. Differing mobility patterns may be one explanation for this. Mitze et al. (2015) examined these by institutional type. Students attending classic universities (as opposed to universities of applied science) migrated more strongly from fee-charging states to non-fee-charging states. Another—potentially interdependent—reason would be the social selectivity of these two tiers (Schindler and Reimer 2011).

There are several limitations of this study. First, I could not ensure that parallel trends assumption holds completely. Although I tested the central premise as described above, I could not rule out any other influences limiting this premise. One major reason for this may be a migration of students from fee-charging to non-fee-charging states during the treatment years. In this case, the differences in enrollment rates between fee-charging and non-fee-charging institutions reflects two factors: On the one hand, there is the substitution effect of inter-institutional migration of students and, on the other hand, the deterrence effect, i.e. (some) high-school graduates may have opted not to go to university. Hence, it is not possible to generalize the results to the introduction of tuition fees throughout Germany: Different tuition rates for students migrating from one federal state to another—of the kind commonly found in U.S. public universities—did not exist in Germany (Mitze et al. 2015). Because of the coexistence of universities with and without tuition fees, high-school graduates migrated to institutions without tuition fees—at least to a certain extent. Such behavior is very likely due to Germany’s small geographical size combined with its good commuting infrastructure. This in turn implies that tuition fees in the treatment group increased the number of enrollments of the control group. Thus, the negative impact of about 7 percent in the main specification does not mean that imposing tuition fees in all German states would engender a similar effect. Loosely speaking, this figures only indicate an upper limit without the existence of substitution effects. In fact, there is evidence that deterrence effects do not exist (Bruckmeier et al. 2015; Mitze et al. 2015). In addition, the data set did not allow me to identify which fields of study were affected and to what extent. Given the need for highly skilled engineers in many German firms, this is an important question. Furthermore, it would be useful to have more individual level data on and analyses of the social structure of those affected by fee imposition (as done by Bahrs and Siedler (2018) for educational intentions) as this was selective by socioeconomic group even before fee introduction (Vossensteyn 2009; Weiss and Steininger 2013). Finally, my dataset did not allow me to analyze the causes of the negative effect of tuition fees (e.g. the lack of credible quality improvements at universities or the lack of scholarship programs) or the effect of so-called “pseudo students” (students who enroll to take advantage of the student status like free public transport), who were probably discouraged by the imposition of fees. These effects could lead to an over- or underestimation.

Concerning future research, there is already limited, albeit sometimes contradictory, evidence on general tuition fees. However, there have hardly been any studies on the price sensitivity of students and specific student groups with regard to specific fees. On the one hand, this applies to foreign students, who make up a not inconsiderable proportion of the newly enrolled students. Since 2017, Baden-Württemberg has charged €1,500 tuitions from foreign students. Vortisch (2023) shows first evidence of a general decline of international student enrollments in the respective state as a result of this policy. In addition, 6 out of 10 federal states charge fees as soon as students exceed the regular period of study (German Student Union 2015). The evidence for this policy is also very limited, only a report for the University of Konstanz in Baden-Württemberg by Heineck et al. (2006) shows slight accelerations in individual subjects, which are offset by an increase in the probability of unsuccessful degrees, changing institutions and dropping out. Furthermore, private higher education institutions in Germany still have a comparatively low relevance (PROPHE 2011) and rather moderate private tuition fees Buschle and Haider (2016), but they are recording rapid growth, considering the 11-fold increase in the number of students between 2001 and 2020 (Federal Statistical Office of Germany 2021) and thus also during the general fee policy. This raises questions on private tuition elasticities and of a potential public–private-interplay, especially in the context of the temporarily intensified competition in Germany, which in the U.S. led to migration between institutions (Astin and Inouye 1988; Perna and Titus 2004). Finally, less obvious in this respect is a growing market in Germany for fee-based offers by public higher education institutions (e.g. in the context of so-called “certificate courses”) and the interaction or competition between these and public offers. In any case, the evidence that examines the marketization tendencies in the tertiary sector needs to be expanded, not only from a general perspective, but also from a perspective of socio-economic segregation. In addition to the general knowledge of higher price sensitivity for general fees (Bahrs and Siedler (2018) for Germany, Coelli (2009) for Canada, Pigini and Staffolani (2016) for Italy or Declercq and Verboven (2015) for the Netherlands), one can assume effect of specific and private fees to affect the composition of the student body in cultural aspects (Vortisch 2023) or socio-economic-gradients (Herrmann 2019). Dealing with specific fees can therefore make a major contribution to preventing socio-economic segregation.

The results for general public tuition fees show that even the introduction of very modest charges led to a relatively strong reaction and show first evidence for a remaining behavioral adjustment among tertiary students in Germany. For some HEIs in FS, this may not have been too problematic, but those institutions that had relatively low student numbers before the introduction of fees and that depended on these numbers for public funding may have been greatly affected. Moreover, the results confirm that the quality improvement argument for tuition fees did not work to stimulate demand or at least this was not justified by additional financial resources (Gawellek et al. 2016). In this event, neither substitution nor deterrence effects should have been at hand. These are relevant outcomes, given that the possibility of the (re-)introduction of tuition fees remains on the political agenda—or has been implemented for subgroups as discussed above. Any discussions should take into account in particular that the tertiary education participation of 25–34 year old’s is still increasing, but behind the EU(-27) average and the European tertiary quota target for 2030 (Eurostat 2023). In this regard, it is unclear to what extent a different fee system would contribute to a lower reduction on student enrollments and, in particular, less to deterring lower socio-economic groups, preventing the potential for segregation mechanisms discussed above.

In the specific case, the rapid introduction of up-front-fees led to much dissatisfaction (Timmermann 2019) but was not associated with quality improvements (Gawellek et al. 2016) or improvements in social equality (Bahrs and Siedler 2018). A rational political debate and future decisions should be based less on ideology and more on empirical evidence (Kauder and Potrafke 2013). All in all, my study has shown that treated HEIs persistently lost students, who are their major sources of talent, renewal, and public funding. The reform put the brakes on the desired expansion of mass tertiary education and represented a costly experiment.

Availability of data and materials

Data is freely available from official bodies and cited in the references section, source code is available upon request.

Notes

Hüther and Krücken (2014) refer to a "Hörergeld" of 120 to 150 German marks in the 1960s (about $420 to $535 at 1971 dollar rate) until this was abolished in 1971 to integrate socially disadvantaged groups.

$564.89 calculated according to the March 2006 dollar rate.

Fees lower than this were only charged in the introductory period and in some exceptional cases. For a list of average fees in the various federal states, see Hübner (2012, p. 951).

This study does not consider other costs, such as administrative fees. Furthermore, the tuition fees referred to only concern primary public higher education. In the public system, fees for long-term students still exist in some states but are not the subject of the present study (see German Student Union (2015) for an overview), same applies for recently introduced fees for foreign students in Baden-Württemberg (see Vortisch (2023)). Furthermore, private higher education institutions do exist and vary in their fee-heights (see Buschle and Haider (2016)).

As HEI entry qualification data were not provided in the German administrative statistics, I could not introduce control variables for first-year students from outside of Germany.

These included non-private traditional universities, technical universities, and universities of applied sciences and universities for technology and business.

Source code available for STATA 16.

Since some specifications are also used for comparison or robustness testing, the modeling of state-specific trends is not applied to all specifications, and in some cases only yearly dummies are used.

References

Alecke, B., Burgard, C., & Mitze, T.: The effect of tuition fees on student enrollment and location choice: Interregional migration, border effects and gender differences (Ruhr economic papers No. 404). Essen. (2013)

Angrist, J.D., Pischke, J.-S.: Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press (2009)

Ashenfelter, O.: Estimating the effect of training programs on earnings. Rev. Econ. Stat. 60(1), 47–57 (1978)

Astin, A., Inouye, C.J.: How public policy at the state level affects private higher education institutions. Econ. Educat. Rev. 7(1), 47–63 (1988)

Autor, D.H.: Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the “other 99 percent.” Science 344(6186), 843 (2014)

Bahrs, M., & Siedler, T.: University Tuition Fees and High School Students' Educational Intentions. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research: Vol. 1008. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW). (2018)

Baier, T., Helbig, M.: Much ado about €500: Do tuition fees keep German students from entering university? Evidence from a natural eperiment using DiD matching methods. Educ. Res. Eval. 20(2), 98–121 (2014)

Baltagi, B.H.: Econometric analysis of panel data (Fifth Edition). Wiley (2013)

Bates, E.A., Kaye, L.K.: “I’d be expecting caviar in lectures”: the impact of the new fee regime on undergraduate students’ expectations of Higher Education. High. Educ. 67(5), 655–673 (2014)

Becker, R., Hecken, A.E.: Warum werden Arbeiterkinder vom Studium an Universitäten abgelenkt? Eine empirische Überprüfung der „Ablenkungsthese“ von Müller und Pollak (2007) und ihrer Erweiterung durch Hillmert und Jacob (2003). KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie 60(1), 7–33 (2008)

Becker, G.S., Mulligan, C.B.: The endogenous determination of time preference. Q. J. Econ. 112(3), 729–758 (1997)

Becker, G. S.: Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). The University of Chicago Press. (1993)

Bietenbeck, J., Leibing, A., Marcus, J., & Weinhardt, F.: Tuition Fees and Educational Attainment (Discussion Paper No. 1839). London, U.K. The London School of Economics and Political Science. (2022)

Bundesweiter Bildungsstreik. Forderungen der Schüler_innen « Bundesweiter Bildungsstreik. https://bildungsstreik.net/aufruf/forderungen-der-schuler_innen/ (2009)

Boix, C.: Political parties and the supply side of the economy: the provision of physical and human capital in advanced economies, 1960–90. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41(3), 814–845 (1997)

Bruckmeier, K., Wigger, B.U.: The effects of tuition fees on transition from high school to university in Germany. Econ. Educ. Rev. 41(2014), 14–23 (2014)

Bruckmeier, K., Fischer, G.-B., Wigger, B.U.: The willingness to pay for higher education: does the type of fee matter? Appl. Econ. Lett. 20(13), 1279–1282 (2013)

Bruckmeier, K., Fischer, G.-B., Wigger, B.U.: Studiengebühren in Deutschland: Lehren aus einem gescheiterten Experiment. Perspekt. Wirtsch. 16(3), 289–301 (2015)

Buchmann, C., DiPrete, T.A., McDaniel, A.: Gender inequalities in education. Annu. Rev. Sociol 34, 319–337 (2008)

Buschle, N., & Haider, C.: Private Hochschulen in Deutschland. Wiesbaden, Germany. Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden, Germany. (2016)

BvF 1/03, 2005: Federal Constitutional Court: Ruling of the Second Senate. https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/2005/01/fs20050126_2bvf000103.pdf;jsessionid=8E3939003B2E79FAF23E4F06F31D1114.2_cid361?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (2005)

Canton, E., de Jong, F.: The demand for higher education in the Netherlands, 1950–1999. Econ. Educ. Rev. 24(6), 651–663 (2005)

Casillas, J. C. S.: The Growth of the Private Sector in Mexican Higher Education. In K. Kinser, D. C. Levy, J. C. S. Casillas, A. Bernasconi, S. Slantcheva-Durst, W. Otieno, R. LaSota (Eds.), Special Issue: The Global Growth of Private Higher Education (pp. 9–21). (2010)

Coelli, M.B.: Tuition fees and equality of university enrolment. Canadian J. Econ. Revue Canadienne. D’économique. 42(3), 1072–1099 (2009)

Dayhoff, D.A.: High school and college freshmen enrollments: the role of job displacement. Quart. Rev. Econ. Busin. 31(1), 91–104 (1991)

de Gayardon, A.: There is no such thing as free higher education: a global perspective on the (many) realities of free systems. High Educ. Pol. 32(3), 485–505 (2019)

Declercq, K., Verboven, F.: Socio-economic status and enrollment in higher education: do costs matter? Educ. Econ. 23(5), 532–556 (2015)

Denny, K.: The effect of abolishing university tuition costs: evidence from Ireland. Labour Econ. 26, 26–33 (2014)

Dietrich, H., Gerner, H.-D.: The effects of tuition fees on the decision for higher education: evidence from a german policy experiment. Economics Bulletin 32(3), 2407–2413 (2012)

Elliott, C., Soo, K.T.: The international market for MBA qualifications: the relationship between tuition fees and applications. Econ. Educ. Rev. 34, 162–174 (2013)

Eurostat. Educational attainment statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Educational_attainment_statistics#Development_of_educational_attainment_levels_over_time (2023)

Federal and State Statistical Offices. National Accounts of the Federal States: Germany from 1991 to 2021. Federal and State Statistical Offices. https://www.statistikportal.de/de/vgrdl/ergebnisse-laenderebene/bruttoinlandsprodukt-bruttowertschoepfung#alle-ergebnisse (2022)

Federal Employment Agency. Unemployment and Unemployment Rates: Germany and Federal States (Time Series Annual Figures from 1950). Federal Employment Agency. https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/SiteGlobals/Forms/Suche/Einzelheftsuche_Formular.html;jsessionid=03A9DAFF4A731B8DCE03D7E28F9FFDD1?nn=1610104&topic_f=laender-heft (2021)

Federal Statistical Office of Germany. GENESIS-Online: Absolventen/Abgänger: Bundesländer, Schuljahr, Geschlecht, Schulabschlüsse, Schulart. Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online/data?operation=table&code=21111-0015&levelindex=1&levelid=1578920527228 (2020a)

Federal Statistical Office of Germany. GENESIS-Online: Studienanfänger: Deutschland, Semester, Nationalität, Geschlecht, Hochschulen. Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online/data?operation=table&code=21311-0011&levelindex=1&levelid=1578920467106 (2020b)

Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Bildung und Kultur: Private Hochschulen. 2019 (Bildung und Kultur). Wiesbaden, Germany. Federal Statistical Office of Germany. (2021)

Gago, J. M., Ziman, J., Caro, P., Constantinou, C., Davies, G., Parchmann, I., Rannikmae, M., & Sjøberg, S.: Europe Needs More Scientists: Report by the High Level Group on Increasing Human Resources for Science and Technology. (2005)

Garibaldi, P., Giavazui, F., Ichino, A., & Rettore, E.: College Cost and Time to Complete a Degree: Evidence from Tuition Discontinuities (NBER Working Paper Series No. 12863). Cambridge, M.A., U.S. (2007)

Garritzmann, J. L.: The Political Economy of Higher Education Finance: The Politics of Tuition Fees and Subsidies in OECD Countries,1945–2015. Springer International Publishing. (2016)

Gawellek, B., Singh, D., Süssmuth, B.: Tuition Fees and Instructional Quality. Econ. Bull. 36(1), 84–91 (2016)

German Parliament. Verwendung von Studiengebühren in Deutschland (WD 8 - 3000 - 036), 1–26. (2009)

German Student Union: Länderregelungen bei Langzeitstudiengebühren. Deutsches Studentenwerk, Berlin (2015)

Gillmann, B. Germany Tech Worker Shortage Gets Worse. https://www.handelsblatt.com/today/companies/stem-skills-germany-tech-worker-shortage-gets-worse/23695034.html?ticket=ST-99281-XtEkUEN5BcfceJdpwiWH-ap4 (2018).

Greene, W. H.: Econometric analysis (Eighth edition). Pearson. (2018)

Havranek, T., Irsova, Z., Zeynalova, O.: Tuition Fees and University Enrolment: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Oxford Bull. Econ. Stat. 80(6), 1145–1184 (2018)

Heine, C., Quast, H., & Spangenberg, H.: Studiengebühren aus der Sicht von Studienberechtigten: Studiengebühren aus der Sicht von Studienberechtigten (HIS: Forum Hochschule 15 | 2008). Hannover. (2008)

Heine, C.: Auswirkung der Einführung von Studiengebühren auf die Studierbereitschaft in Deutschland. Öffentliches Fachgespräch im Bundestagsausschuss für Bildung, Forschung und Technologiefolgenabschätzung am 25. Januar 2012 in Berlin (HIS: Stellungnahme). HIS-Institut für Hochschulforschung. (2012)

Heineck, M., Kifmann, M., & Lorenz, N:. A Duration Analysis of the Effects of Tuition Fees for Long-Term Students in Germany. In: W. Franz (Ed.), Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik: 226/1. Education and Mobility in Heterogeneous Labor Markets (pp. 82–109). De Gruyter Oldenbourg. (2006)

Helbig, M., Baier, T., Kroth, A.: Die Auswirkung von Studiengebühren auf die Studierneigung in Deutschland: Evidenz aus einem natürlichen Experiment auf Basis der HIS-Studienberechtigtenbefragung. Z. Soziol. 41(3), 227–246 (2012)

Heller, D.E.: Student price response in higher education: an update to Leslie and Brinkman. J. Higher Educ. 68(6), 624–659 (1997)

Heller, D.E., Rogers, K.R.: Shifting The Burden: Public and Private Financing of Higher Education in the United States and Implications for Europe. Tert. Educ. Manag. 12(2), 91–117 (2006)

Hemelt, S., Marcotte, D.: The Impact of Tuition Increases on Enrollment at Public Colleges and Universities. Educ. Eval. Policy. Anal. 33(4), 435–457 (2011)

Herrmann, S.: Sozioökonomische Merkmale und Erwartungen von Studierenden privater Hochschulen in Deutschland (Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung 2/2019). (2019)

Hsing, Y., Chang, H.S.: Testing Increasing Sensitivity of Enrollment at Private Institutions to Tuition and Other Costs. Am. Econ. 40(1), 40–45 (1996)

Hübner, M.: Do tuition fees affect enrollment behavior? Evidence from a “natural experiment” in Germany. Econ. Educ. Rev. 31(6), 949–960 (2012)

Huisman, J., Kaiser, F., Vossensteyn, H.: Floating Foundations of Higher Education Policy. High. Educ. q. 54(3), 217–238 (2000)

Hüther, O., & Krücken, G.: The Rise and Fall of Student Fees in a Federal Higher Education System: the case of Germany. In: H. Ertl & C. Dupuy (Eds.), Oxford studies in comparative education. Students, Markets and Sozial Justice: Higher education fee and student support politics in Western Europe and beyond pp. 85–110 (2014)

Hüther, O., & Krücken, G.: Higher Education in Germany—Recent Developments in an International Perspective (Vol. 49). Springer International Publishing. (2018)

Johnson, M.T.: Borrowing constraints, college enrollment, and delayed entry. J. Law. Econ. 31(4), 669–725 (2013)

Johnstone, D.: The economics and politics of cost sharing in higher education: comparative perspectives. Econ. Educ. Rev. 23(4), 403–410 (2004)

Kalenkoski, C.M., Pabilonia, S.W.: Parental transfers, student achievement, and the labor supply of college students. J. Popul. Econ. 23(2), 469–496 (2010)

Kauder, B., & Potrafke, N.: Government ideology and tuition fee policy: evidence from the German states. Munich. Ifo Institute. (2013)

Keane, M.P., Wolpin, K.I.: The effect of parental transfers and borrowing constraints on educational attainment. Int. Econ. Rev. 42(4), 1051–1103 (2001)

Kivinen, O., Ahola, S., Hedman, J.: Expanding education and improving odds? Participation in higher education in Finland in the 1980s and 1990s. Acta Sociologica 44(2), 171–181 (2001)

Leslie, L.L., Brinkman, P.T.: Student price response in higher education: the student demand studies. J. High. Educ. 58(2), 181–204 (1987)

Leszczensky, M.: Paradigmenwechsel in der Hochschulfinanzierung (Beilage zur Wochenzeitung Das Parlamanet: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte B 25). Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. (2004)

Machin, S., McNally, S.: Tertiary education systems and labour markets: a paper commissioned by the education and training policy division (Tertiary Review). OECD, Paris (2007)

Meyer, B.D.: Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J. Busin. Econ. Stat. 13(2), 151–161 (1995)

Mitze, T., Burgard, C., Alecke, B.: The tuition fee ‘shock’: analysing the response of first-year students to a spatially discontinuous policy change in Germany. Pap. Reg. Sci. 94(2), 385–419 (2015)

Neill, C.: Tuition fees and the demand for university places. Econ. Educ. Rev. 28(5), 561–570 (2009)

Neill, C.: Rising student employment: the role of tuition fees. Educ. Econ. 23(1), 101–121 (2014)

Perna, L.W., Titus, M.A.: Understanding differences in the choice of college attended: the role of state public policies. Rev. High. Educ. 27(4), 501–525 (2004)

Pigini, C., Staffolani, S.: Beyond participation: do the cost and quality of higher education shape the enrollment composition? The Case of Italy. High. Educ. 71(1), 119–142 (2016)

PROPHE. (2011). Global Private and Total Higher Education Enrollment by Region and Country, 2010. http://www.prophe.org/en/global-data/global-data/global-enrollment-by-region-and-country/

Schindler, S., Reimer, D.: Differentiation and social selectivity in German higher education. High. Educ. 61(3), 261–275 (2011)

Schofer, E., Meyer, J.W.: The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 70(6), 898–920 (2005)

Shin, J.C., Milton, S.: Student response to tuition increase by academic majors: empirical grounds for a cost-related tuition policy. High. Educ. 55(6), 719–734 (2008)

The World Bank Group. Fertility rate, total (births per woman). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=DE (2020)

Timmermann, D.: The Abolition of Tuition Fees in Germany: Student Protests and Their Impact. In W. Archer & H. G. Schuetze (Eds.), Preparting Students for Life and Work: Policies and Reforms Affecting Higher Education´s Principal Mission (pp. 204–219). Brill | Sense. (2019)

Trow, M.: The expansion and transformation of higher education. Int. Rev. Educat. 18(1), 61–84 (1972)

Türkoğlu, D.: Ever Failed? Fail Again, Fail Better: Tuition Protests in Germany, Turkey, and the United States. In L. Cini, D. Della Porta, & C. Guzmán-Concha (Eds.), Springer eBook Collection. Student Movements in Late Neoliberalism: Dynamics of Contention and Their Consequences (1st ed., pp. 269–292). Springer International Publishing; Imprint Palgrave Macmillan. (2021)

Vortisch, A.B.: The land of the fee: the effect of Baden-Württemberg’s tuition fees on international student outcomes. Educat. Econ. 5, 1–26 (2023)

Vossensteyn, H.: Challenges in student financing: state financial support to students – a worldwide perspective. High. Educ. Eur. 34(2), 171–187 (2009)

Weiss, F., Steininger, H.-M.: Educational family background and the realisation of educational career intentions: participation of German upper secondary graduates in higher education over time. High. Educ. 66(2), 189–202 (2013)

Wooldridge, J. M.: Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (5th ed.). CENGAGE Learning Custom Publishing. (2012)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to Matthias-Wolfgang Stoetzer who motivated and supported me in this project and to the Research Colloquium of the Methods of Empirical Social Research Unit of the Institute of Sociology at Friedrich Schiller University Jena, who enriched the early drafts of this paper with their comments.

Funding

No specific funding has been provided for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The work on this paper was done entirely by the reference author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Summary statistic by fee-charging states and non-fee-charging states. Table S2. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variable [count] and upper secondary school graduates by gender. Table S3. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variable [count] by type of institution. Table S4. Effect of temporary tuition fee charges on the log of enrollments at public higher education institutions controlling for “double cohorts”

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix 1 Effect of temporary tuition fee charges on the log of first-year-student enrollments at public higher education institution by institutional type subgroups

(1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

Universities | Universities of Applied Sciences | |

Public tuition fee charging [dummy] | − 0.0655*** | − 0.0776*** |

(− 4.85) | (− 4.54) | |

One year lead in treatment | − 0.00359 | 0.00918 |

(− 0.25) | (0.46) | |

Two year lead in treatment | − 0.0165 | − 0.0397 |

(− 0.56) | (− 1.58) | |

Upper secondary school graduates [in thousands] | 0.00270*** | 0.00444*** |

(5.22) | (4.97) | |

One year lag of graduates [in thousands] | 0.00136*** | 0.000325 |

(3.40) | (0.82) | |

Two year lag of graduates [in thousands] | 0.000175 | 0.000421 |

(0.47) | (0.85) | |

Unemployment rate [percentage] | − 0.0191 | − 0.0252* |

(− 1.57) | (− 2.34) | |

Vocational training contracts acquired | 0.000000700 | − 0.00000408* |

(0.37) | (− 2.19) | |

Gross domestic product [per capita] | 0.000000500 | − 0.00000108 |

(0.09) | (− 0.30) | |

Proportion of bachelor-degrees and master-degrees | 0.00991*** | 0.00731*** |

(6.14) | (4.91) | |

Federal state specific year trend | ✓ | ✓ |

Observations | 1,572 | 900 |

Coefficients of Fixed effects regression with cluster robust standard errors (institutional level);

t statistics in parentheses; *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Appendix 2 Effect of temporary tuition fee charges on the log of enrollments at public higher education institution by gender

(1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

Female enrollments | Male enrollments | |

Public tuition fee charging [dummy] | − 0.0872*** | − 0.0578*** |

(− 7.32) | (− 3.59) | |

One year lead in treatment | 0.00766 | 0.00233 |

(0.51) | (0.16) | |

Two year lead in treatment | − 0.0411 | − 0.00707 |

(− 1.85) | (− 0.29) | |

Female upper secondary school graduates [in thousands] | 0.00576*** | |

(5.82) | ||

One year lag of female graduates [in thousands] | 0.00101 | |

(1.66) | ||

Two year lag of female graduates [in thousands] | 0.000390 | |

(0.62) | ||

Male upper secondary school graduates [in thousands] | 0.00761*** | |

(6.92) | ||

One year lag of male graduates [in thousands] | 0.00441*** | |

(4.63) | ||

Two year lag of male graduates [in thousands] | 0.00111 | |

(1.27) | ||

Unemployment rate [percentage] | − 0.0131 | − 0.0303** |

(− 1.38) | (− 3.09) | |

Vocational training contracts acquired | − 0.00000213 | 0.00000134 |

(− 1.40) | (0.68) | |

Gross domestic product [per capita] | 0.00000447 | − 0.00000316 |

(1.19) | (− 0.65) | |

Proportion of bachelor-degrees and master-degrees | 0.0118*** | 0.00609*** |

(9.16) | (4.41) | |

Federal state specific year trend | ✓ | ✓ |

Observations | 2,472 | 2,472 |

Coefficients of Fixed effects Poisson regression with cluster robust standard errors (institutional level);

t statistics in parentheses; *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Appendix 3 Effect of temporary tuition fee charges on the count of enrollments at federal state level

(1) | |

|---|---|

Fixed Effects Regression (Aggregate) | |

Public tuition fee charging [dummy] | − 0.0547** |

(− 2.48) | |

One year lead in treatment | 0.0024 |

(0.11) | |

Two year lead in treatment | 0.0104 |

(0.30) | |

Upper secondary school graduates [in thousands] | 0.0042*** |

(3.26) | |

One year lag of graduates [in thousands] | 0.0020* |

(2.07) | |

Two year lag of graduates [in thousands] | 0.0012 |

(1.05) | |

Unemployment rate [percentage] | 0.0285 |

(1.56) | |

Vocational training contracts acquired | 0.0000 |

(0.62) | |

Gross domestic product [per capita] | − 0.0000** |

(− 2.45) | |

Proportion of bachelor-degrees and master-degrees | 0.0054 |

(1.53) | |

Year [dummies] | ✓ |

Observations | 192 |

Coefficients of Fixed effects regression with cluster robust standard errors (federal state level);

t statistics in parentheses; *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Appendix 4 Comparison of the effects of temporary tuition charging on enrollments at public higher education institutions for different study periods

(1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Estimation until 2018 | Estimation until 2010 | Estimation until 2008 | |

Public tuition fee charging [dummy] | − 0.0651*** | − 0.0494* | − 0.0448* |

(− 4.16) | (− 2.36) | (− 2.45) | |

One year lead in treatment | − 0.0296** | − 0.00663 | 0.00963 |

(− 2.76) | (− 0.62) | (0.68) | |

Two year lead in treatment | 0.0135 | 0.0198 | 0.0435** |

(1.05) | (1.30) | (2.82) | |

Upper secondary school graduates [in thousands] | 0.0113*** | 0.0197*** | 0.00327 |

(5.27) | (4.84) | (0.59) | |

Upper secondary school graduates [in thousands, squared] | − 0.0000530*** | − 0.000139** | − 0.0000650 |

(− 3.36) | (− 2.89) | (− 1.04) | |

Unemployment rate [percentage] | 0.0467*** | 0.0122 | 0.0128 |

(6.86) | (1.45) | (1.32) | |

Year [dummies] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Observations | 2,884 | 1,648 | 1,236 |

R2 (within) | 0.4205 | 0.2994 | 0.2093 |

Coefficients of Fixed effects regressions with cluster robust standard errors (institutional level);

t statistics in parentheses; *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Appendix 5 Overview of treatment coefficients from fixed effect regression models, sequentially leaving one federal state out of the specification [legend based on official federal state codes]

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Minor, R. How tuition fees affected student enrollment at higher education institutions: the aftermath of a German quasi-experiment. J Labour Market Res 57, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-023-00354-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-023-00354-7