Abstract

Background

Ureteric avulsion is a disastrous intraoperative complication that can happen to any urologist during a common endoscopic procedure like ureteroscopy. The aim of this study is to evaluate the various management options of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy and also report our relevant experience in this topic.

Results

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of existing literature in English language was used in the period 1967–2019 with a literature search in PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar. Forty-three patients in twenty-three articles who had undergone management of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy were identified for review. There were 15 proximal, 19 two-point (“scabbard”) and 9 distal avulsions. All distal avulsions were managed successfully with ureteroneocystostomies or Boari flaps. Boari flaps and ureteropyelostomy with ureterovesicostomy were the common procedures used for proximal avulsions. Proximal avulsions had more varied outcomes with salvage rates of 86.9%. Procedures which incorporated the avulsed distal ureter for reconstruction had poor results.

Conclusion

Management of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy is a surgical challenge. While management of distal avulsions is straightforward in the form of ureteroneocystostomies and has uniformly good results in most hands, proximal avulsions need expertise in management and choosing ideal reconstruction, with variable results following reconstruction. Extended Boari flaps, ileal ureter and autotransplantation are good options for proximal avulsions. Reconstruction using the distal avascular ureter should be avoided for better long-term results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Ureteric avulsion is one of the most serious intraoperative complication of ureteroscopy leading to considerable morbidity for the patient, if not properly managed. Inappropriate management of ureteral avulsion often leads to undesirable complications such as obstructive uropathy, urine leakage, retroperitoneal urinoma and, sometimes, eventual nephrectomy. Fortunately, even with the rapid advances in endourology and the increase in number of ureteroscopies, the incidence of avulsion is still rare and occurring only in 0–0.3% patients [1, 2]. Since the initial report of Hart in 1967, the literature on management of this disastrous complication has been mostly limited to isolated case reports and small case series [3]. Being an uncommon complication, the management of this condition is still not standardized. There is a plethora of procedures described in literature for management of this complication ranging from simple ureteroneocystostomies for distal avulsions to autotransplantation for proximal avulsions. In the following, we present our experience and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) review of the existing literature in this topic with the purpose of evaluating various management options and to identify the best strategy for management of this unique complication of ureteroscopy.

2 Main text

After getting institutional board approval we reviewed our electronic records of ureteroscopies done in our tertiary centre from November 2010 to March 2019. During this period, we had performed 4802 ureteroscopies for ureteral stones and had managed two ureteric avulsions during ureteroscopy which is an incidence of 0.04%. The ureters were injured during the process of retrograde examination with an 8/9.8 Fr ureteroscope (Karl Storz®). Both the cases were in-house avulsions and happened when ureteroscopies were done by residents in training. Standard operating protocol for ureteroscopy was followed in both the cases in the form of placement of a safety guidewire first with cystoscopy followed by balloon dilatation of ureteric orifice before placement of the ureteroscope.

The first patient was a 43-year-old female who underwent ureteroscopy for a proximal ureteric stone of size 8 mm, impacted 2 cm below the pelviureteric junction. During ureteroscopy, after successful stone fragmentation and removal, when the surgeon made a forceful attempt to enter pelvis, there was a sudden giveaway and avulsion was suspected. The ureteroscope was removed slowly, and when re-entry was attempted, no lumen could be identified as the surgeon directly entered the retroperitoneum which suggested avulsion and intussusception just outside the ureteric orifice. The second patient was a 34-year-old female who underwent ureteroscopy for a 9-mm proximal ureteric calculus. After insertion of ureteroscope up to the midureter, there was mild resistance felt at the level of distal ureter. The surgeon was able to reach the stone after manoeuvring, and the stone was fragmented and disimpacted. The stone was grasped with forceps, and while withdrawing the scope, there was a loss of resistance felt. When the ureteroscope was withdrawn out, a segment of ureter of length 5 cm was seen protruding from the urethral meatus which confirmed avulsion.

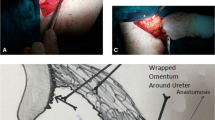

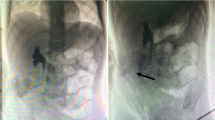

Reconstruction for both the avulsions were performed by open surgical approach. As soon as avulsion was diagnosed in the first patient, a nephrostomy was placed under ultrasound guidance. We later discussed the treatment options with the patient in the form of an ileal ureter, autotransplantation or a nephrectomy and the patient opted for an ileal ureter. A preoperative antegrade study was done a week after the injury which showed complete cut-off at pelvi-ureteric junction and small contracted intrarenal pelvis. After adequate bowel preparation, exploration was done which revealed a small, fibrotic intrarenal pelvis and hence we decided to perform an ileocalicostomy. The lower pole was transected, a 15 cm length of distal ileum was isolated, and ileal interposition was done. The anastomosis was stented with a 12-Fr Ryles tube which was brought out through a cystotomy separately. A retrograde study was done through the Ryles tube at 6 weeks (Fig. 1), and it was removed after confirming no leak. The patient was followed up with ultrasonography every 3 months, and an intravenous urography at 2 year showed good excretion with no hydronephrosis.

In the second patient after the diagnosis of avulsion was made, the avulsed segment was pushed back into the bladder, and immediately under fluoroscopic guidance, a nephrostomy was placed. An antegrade study confirmed avulsion at the level of the pelvic brim. The patient was explained about the complication and the treatment options in the form of ureteric reimplantation with a psoas hitch or a Boari flap. After getting informed consent, we explored the patient through a left Gibson’s incision and found the proximal ureteric end close to the level of iliac bifurcation. On cystotomy, 3 cm of avascular distal ureter was found within the bladder (Fig. 2a). A refluxing ureteroneocystostomy with a psoas hitch was done over a 5-Fr DJ stent (Fig. 2b). The stent was removed after 6 weeks, and nephrostomy was removed after an antegrade study which confirmed no leak (Fig. 2c). She was followed up with 3 monthly ultrasound which showed complete resolution of hydronephrosis and is doing well at 18-month follow-up. Time from injury to definitive surgery was 7 days and 12 h for both the cases, respectively.

A systematic review was made according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (P.R.I.S.M.A) protocol. The included articles were selected according to PRISMA flow diagram principles (Fig. 3). A comprehensive electronic English language literature search was performed using MeSH Terms in PubMed with the following search strings: ‘avulsion’ [Mesh]) AND ‘ureter’ [Mesh], ‘avulsion’ [Mesh]) AND ‘ureteroscopy’ [Mesh], ‘ureteroscopy’ [Mesh]) AND ‘complications’ [Mesh] to identify articles on management of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy. In addition, Cochrane library and Google Scholar were searched with equivalent strings. A total of 147 articles were found via database searches. The references were imported for sorting and controlled for duplicates. Articles regarding management of avulsions following trauma or iatrogenic causes, articles in languages other than English and articles that clearly did not meet our criteria were excluded. Reference lists from all selected articles were reviewed, and if necessary, abstracts and full articles were assessed for inclusion. The search was without time limit and includes all available literature until 31 December 2019. Only studies in English were included. In total, twenty-three articles were identified which explicitly reported on the management of ureteric avulsion following ureteroscopy. Age, sex, side, indications, ureteroscope used, energy source used, mechanism of avulsion, level of avulsion, timing of surgery, type and manner of reconstruction, follow-up and complications were recorded.

Forty-three patients in twenty-three published articles in English, including fifteen case reports and eight small series (n < 7), had undergone management of ureteric avulsion following ureteroscopy and were included in our review. Data related to age, sex, side, level of avulsion, timing of surgery, type and manner of reconstruction, follow-up and complications were recorded and are summarized in Table 1.

The age at surgery ranged from 32 to 78 years; excluding two studies where the age and sex distribution of patients was not mentioned, there were 24 males and 13 females (male to female ratio = 1.8:1) and left side was more commonly involved. While the initial reports of avulsion were following stone manipulation with Dormia baskets and were managed with nephrectomies, the first report of successful salvage of kidney following ureteroscopic avulsion was in 2000 by Fabrizio et al. who reported a proximal avulsion in a 41-year-old man successfully managed with a laparoscopic nephrectomy and autotransplantation [3,4,5,6]. Among these 43 patients, there were 15 proximal, 19 two-point or “scabbard” and 9 distal avulsions (Table 1). Of these patients, 30 were managed immediately and 7 were managed in a delayed manner and timing of surgery was not mentioned in 6 patients in the series by Tae et al. [7]. Primary open approach was used in the majority of cases (38/43) with laparoscopic assistance used in 3 cases [7, 8]. Endoscopic approach in the form of retrograde and antegrade realignment was used primarily for 4 patients [9,10,11]. Primary nephrectomy was done in seven patients [3, 4, 8, 12, 13]. As shown in Table 2, the rest (36) had undergone various reconstructive procedures. After excluding 6 patients on whom follow-up data were not available, the overall salvage rate following reconstructive procedures for avulsions was 86.7% (26/30). While all the distal avulsions managed with ureteroneocystostomies and Boari flap had successful outcomes, proximal avulsions had more varied outcomes with salvage rates of 86.9% (20/23). Boari flaps (8) and ureteropyelostomy with ureterovesicostomy (7) were the common procedures used for proximal avulsions. The worst outcomes were seen following ureteropyelostomy with ureterovesicostomy where of the 8 cases managed this way only three kidneys (42.9%) were successfully salvaged (including one needing redo reimplantation) with four losing function over time and ultimately leading to nephrectomy in three. Interestingly, when we analysed all procedures where the distal ureter has been preserved (ureteropyelostomies, ureteropyelostomy with ureterovesicostomy and endoscopic management), the primary salvage rate was dismal 33.3% which improved to only 60% after further secondary procedures.

Ureteral avulsion is a rare but serious complication; fortunately, its incidence is only 0 to 0.3% which is similar to the incidence in our centre (0.04%) [1, 2]. Although ureteral avulsion is rare, this catastrophic complication should be kept in mind while performing an ureteroscopy, and a urologist should be familiar with management options in different avulsion scenarios. Due to the rarity of occurrence and the paucity of literature on this complication, there is no standard management protocol for this complication which leads to lot of confusion regarding the safe and effective management of this complication and many times young urologists are left wanting when they are faced with this unexpected serious complication.

Multiple factors are involved in the decision making while managing avulsion. Patient factors include level of avulsion, 2-point (“scabbard”) or single-point avulsion and comorbidities of the patient which in turn will decide fitness for major reconstructive surgery [8]. One factor that has not commonly being addressed is the issue of patient consent, as consent for major reconstructive procedures is not usually part of consent for ureteroscopy. We feel that it is wise to allow the patient and patient relatives to consider their options with a clear mind outside the operation theatre, instead of rushing them to decide immediately at the time of primary procedure. Though avulsion is a serious complication leading to morbidity its seldom a life-threatening complication if managed properly, hence a few hours spent on planning the course of events is always better for both the patient and the surgeon.

Another important factor is surgeon experience. Though ureteroscopy is a fairly common procedure which is done by trainee’s also, management of avulsion needs the expertise of an experienced urologist who is well versed with various ureteral reconstructive procedures. In fact, we believe that this is the single most important factor that decides the management course of a patient with avulsion. If adequate expertise is available, then the patient can be given all the options of surgical management depending on the various patient factors elucidate above and the patient can be taken up for reconstruction as soon as possible. In the unfortunate circumstance that adequate surgical expertise is unavailable which is often the case in many developing countries, then one good option is to place a nephrostomy percutaneously (as we did in both of our patients) and then plan for reconstruction either when expertise becomes available in the same centre or the patient can be referred to a higher centre with necessary expertise. Even in situations where adequate expertise is available, we believe that nephrostomy placement is an ideal initial step before reconstruction, especially in proximal avulsions. Apart from preventing urinoma formation, nephrostomy placement has the added advantage of allowing the surgeon to know the exact level of avulsion by an antegrade study and also it allows the surgeon to wait safely while proper preoperative assessment (bladder capacity, in cases for Boari flap) and preparation (bowel preparation for ileal reconstruction) are done in the patient planned for major reconstruction. Further the patient is given enough time to get over the initial shock of an avulsion and understand the pros and cons of each surgical option before giving the consent for the definitive reconstructive procedure. Due to the above advantages of a nephrostomy, as shown in our series we placed a nephrostomy in both the patients and took the patients electively in a delayed manner.

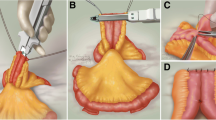

As shown in Table 2, various surgical options depend on the level of avulsion and the length of ureter to be replaced. In the distal ureter, the treatment is relatively straight forward in the form of ureteroneocystostomy with or without a psoas hitch or a Boari flap in most of the cases; rarely, a transureteroureterostomy can also be used [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Management of proximal ureteric avulsions is more complex. The primary concern when it comes to surgery for proximal avulsion is the difficulty in assessing the vascularity of the avulsed distal segment. In cases where there has been minimal displacement of the avulsed ends, ureteropyelostomies and ureteroureterostomies can work [15, 16]. However, in most cases of complete avulsion, distal ureter is stripped of vascularity and we have to resort to the traditional options of extended Boari flaps, autotransplantation or bowel transposition. Though Boari flaps have been traditionally a part of the surgical armamentarium for replacement of distal ureter, it is a good option in proximal avulsions also provided the bladder capacity is good [18,19,20]. In centres with transplant expertise, autotransplantation is a good alternative with the nephrectomy part being done either by open or laparoscopic method [7, 21,22,23]. In spite of the complications associated with bowel interposition, ileal replacement still remains a good versatile option for replacement of long segments of ureter with proximal anastomosis to pelvis or lower pole calyx in cases where pelvis is fibrosed as was the case in our first patient [7, 13, 14, 24, 25]. However, one drawback of this procedure is ideally it has to be done in a delayed manner after assessing the suitability of bowel for interposition and adequate bowel preparation. Appendix interposition has also been reported as a treatment option for extensive injuries in some literature [26]. Apart from these traditional options, there have been reports in the literature especially in two-point or “scabbard” avulsions, where the avulsed ureter has been retrieved, preserved in saline and anastomosed proximally to remnant ureter or the pelvis and distally to the bladder with a greater omentum wrap for vascularity [27,28,29]. Though this procedure looked tempting as it can be done immediately and easily, our analysis shows that this temptation should be avoided as the long-term results are not good due to the poor vascularity of the avulsed ureter, which ultimately fibrosed and, if not detected early, leads to silent loss of the renal unit. Endoscopic management in the form of antegrade and retrograde realignment of distracted segments has been described in literature; however, as we have already mentioned, the concern continues to be vascularity which depends on the extent of displacement of the avulsed segments [9,10,11]. These patients have to be followed up rigorously for development of strictures and may require secondary reconstructive procedure for salvaging renal function [9,10,11]. Finally, nephrectomy is also an immediate option where the function of concerned kidney is already deranged and sometimes as a last resort following failed reconstructions especially in older patients. Based on our observations, we have devised a treatment algorithm for avulsion as shown in Fig. 4.

We believe this review would be helpful in adding vital information to the existing literature on management and long-term outcomes of reconstructive procedures for this dreaded complication, as the present literature is confined to only isolated case reports and naturally, being a very rare complication, a prospective study is not possible with regard to this specific complication. With endourologic procedures becoming part of basic urologic armamentarium which is done by the youngest trainees too, the risk of avulsions though rare still remains and knowledge of best management options and long-term results is vital for proper patient counselling and clinical decision making.

3 Conclusion

To conclude, management of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy is a surgical challenge. While management of distal avulsions is standardized in the form of ureteroneocystostomies and can be done by most urologists, management of proximal avulsions needs expertise and ideally should be managed in higher centres. Though there are various options available for proximal ureteric reconstruction, ideal options for better long-term results include extended Boari flap, ileal ureter or an autotransplantation, if transplant expertise is available. Further, usage of the avulsed distal ureter should be avoided in reconstructive procedures as these procedures give poor long-term results.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

Tanimoto R, Cleary RC, Bagley DH et al (2016) Ureteral avulsion associated with ureteroscopy: insights from the MAUDE database. J Endourol 30:257–261

Perez Castro E, Osther PJ, Jinga V et al (2014) Differences in ureteroscopic stone treatment and outcomes for distal, mid-, proximal, or multiple ureteral locations: the Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society ureteroscopy global study. Eur Urol 66:102–109

Hart JB (1967) Avulsion of distal ureter with Dormia basket. J Urol 97:62

Hodge J (1973) Avulsion of a long segment of ureter with Dormia basket. Br J Urol 45:328

Abdel Sayed M, Onal E, Wax SH (1977) Avulsion of the ureter caused by stone basket manipulation. J Urol 118:868–870

Fabrizio MD, Kavoussi LR, Jackman S et al (2000) Laparoscopic nephrectomy for autotransplantation. Urology 55:145

Taie K, Jasemi M, Khazaeli D et al (2012) Prevalence and management of complications of ureteroscopy: a seven year experience with introduction of a new maneuver to prevent ureteral avulsion. Urol J 9:356–360

Ordon M, Schuler TD, Honey RJ (2011) Ureteral avulsion during contemporary ureteroscopic stone management: “the scabbard avulsion”. J Endourol 25:1259–1262

Zattoni F, Gasparini D, Sponza M et al (2008) Endovascular snare kit in the combined antegrade and retrograde management of ureteral avulsion: report of two cases. Urol Res 36:123–125

El Tayeb M, Mellon MJ, Lingeman JE (2015) Simultaneous percutaneous nephrolithotomy and early endoscopic ureteric realignment for iatrogenic ureteropelvic junction avulsion during ureteroscopy. Can Urol Assoc J 9:882–885

Rouhani MJ, Abboudi H, Gibbons N et al (2017) Endourologic management of an iatrogenic ureteral avulsion using a thermoexpandable nickel–titanium alloy stent (Memokath 051). J Endourol Case Rep 3(1):57–60

Alapont JM, Broseta E, Oliver F et al (2003) Ureteral avulsion as a complication of ureteroscopy. Int Braz J Urol 29:18–23

Gupta V, Sadasukhi TC, Sharma KK et al (2005) Complete ureteral avulsion. Sci World J 28:125–127

Sevinc C, Balaban M, Ozkaptan O et al (2016) The management of total avulsion of the ureter from both ends: our experience and literature review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 88:97–100

Ge C, Li Q, Wang L et al (2011) Management of complete ureteral avulsion and literature review: a report on four cases. J Endourol 25:323–326

Tsai PJ, Wang HYJ, Chao TB et al (2014) Management of complete ureteral avulsion in ureteroscopy. Urol Sci 25:161–163

Unsal A, Oguz U, Tuncel A et al (2013) How to manage total avulsion of the ureter from both ends: our experience and literature review. Int Urol Nephrol 45:1553–1560

Chang SS, Koch MO (1996) The use of an extended spiral bladder flap for treatment of upper ureteral loss. J Urol 156:1981–1983

Ceifo W, Al-Tahweed A, Gawish M (2015) Complete ureteral avulsion during ureteroscopy: a case report. Kuwait Med J 47:251–253

Grzegółkowski P, Lemiński A, Słojewski M (2017) Extended Boari-flap technique as a reconstruction method of total ureteric avulsion. Cent Eur J Urol 70:188–191

Meng MV, Freise CE, Stoller ML (2003) Expanded experience with laparoscopic nephrectomy and autotransplantation for severe ureteral injury. J Urol 169:1363–1367

Lutter I, Molcan T, Pechan J et al (2002) Renal autotransplantation in irreversible ureteral injury. Bratisl Lek Listy 103:437–439

Alizadeh M, Valizadeh R, Rahimi MM (2017) Immediate successful renal autotransplantation after proximal ureteral avulsion fallowing ureteroscopy: a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2:1

Armatys SA, Mellon MJ, Beck SDW et al (2009) Use of ileum as ureteral replacement in urological reconstruction. J Urol 181:177–181

Gaizauskas A, Markevicius M, Gaizauskas S et al (2014) Possible complications of ureteroscopy in modern endourological era: two-point or ‘scabbard’ avulsion. Case Rep Urol 2014:308093

Lloyd SN, Kennedy C (1989) Autotransplantation of the vermiform appendix following ureteroscopic damage to the right ureter. Br J Urol 63:216–217

Gao P, Zhu J, Zhou Y et al (2013) Full-length ureteral avulsion caused by ureteroscopy: report of one case cured by pyeloureterostomy, greater omentum investment, and ureterovesical anastomosis. Urolithiasis 41:183–186

Tepeler A, Resorlu B, Sahin T et al (2014) Categorization of intraoperative ureteroscopy complications using modified Satava classification system. World J Urol 32:131–136

Tang K, Sun F, Tian Y et al (2016) Management of full-length complete ureteral avulsion. Int Braz J Urol 42:160–164

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASP analysed and interpreted the patient data along with analysis of the articles on avulsion and was major contributor to writing the manuscript. GK. DR, AD performed the collection of patient data and review data and were a major contributor in editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval by the institutional ethical committee has been waived (being a retrospective case series). Our institution does not require ethical approval for such retrospective case series. Written informed consent for the patient’s participation was obtained.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for the publication of this data was given by the patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Shekar, P.A., Kochhar, G., Reddy, D. et al. Management of ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy: a systematic review and our experience. Afr J Urol 26, 58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00078-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00078-x