Abstract

Background

It is overwhelmingly acknowledged by the scientific community that evolution and global climate change (GCC) are undeniably supported by physical evidence. And yet, both topics remain politically contentious in the United States. It is thought that students’ conceptions of the nature of science (NOS) may be key factors in their attitudes towards evolution and GCC. Our study explored this hypothesis guided by the following questions: Do changes in NOS conceptions correlate with changes in attitudes towards evolution or GCC? If there are correlations, are they similar for evolution and GCC? What demographic factors affect these correlations?

Methods

Previously-developed tools were used to measure students’ conceptions of the nature of science and attitudes towards evolution, while national public opinion poll questions were used to measure attitudes towards GCC. Demographic questions were produced to target factors thought to influence attitudes towards evolution or global climate change. Overall sample size was N = 620. Principle components analysis was used to determine which variables accounted for the most variation, and those variables were analyzed using correlation tests, ANOVA, and ANCOVA to test for significant correlations and interaction effects.

Results

Changes in students’ attitudes towards evolution and global climate change were both positively correlated with shifts in conceptions about the nature of science. Attitudes towards evolution were negatively correlated with religiosity. Knowledge of evolutionary science was positively correlated with attitudes towards evolution, but knowledge about GCC was not significantly correlated with attitudes towards GCC. The strongest correlates of GCC attitudes were political leanings.

Conclusions

Findings support the hypothesis that a better understanding of NOS may lead to changes in attitudes towards politically contentious ideas that are not scientifically contentious. Though attitudes towards evolution correlated strongly and significantly with a number of other factors including knowledge of evolutionary science and religiosity, expected non-political correlates with attitudes towards GCC were absent. Giving students a good conception of the modern nature of science may lead to views that are closer to those of the scientific community. This study provides novel evidence of a linkage between student acceptance of evolution and attitudes towards GCC, that is, NOS conceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evolution, as defined broadly and narrowly, includes the fact that the living organisms of today differ from those of the past, the evidence-based inference that the diversity we now see has arisen via descent with modification from an ancient ancestry, and the organic mechanisms though which biological change occurs (Eldredge [2005]; Gould [1981]; Scott [2004]; Wiles and Alters [2011]). As it is defined in the textbook assigned to the student participants in this study, evolution is ‘the process of change that has transformed life on Earth from its earliest beginnings to the diversity of organisms living today’ (Reece et al. [2011]). Biologists and life science educators have long known that ‘nothing in biology makes sense except in light of evolution’ (Dobzhansky [1973]). Evolution is supported by evidence from many sources, from genetics to embryology to geology, and it has been directly observed in numerous species in laboratories and in nature. There are no scientifically supported, evidence-based alternative explanations for changes within species or the origin of new species (American Institute of Biological Sciences [1994]). Evolution is widely regarded as a central and unifying theme in the biological sciences, and it is presented as such in most modern biology texts (Wiles [2010]). Within the scientific community, there is debate over the relative impacts of the known mechanisms by which evolution occurs, but none over whether or not evolution has occurred or continues to happen.

Although evolution has been overwhelmingly accepted by the scientific community (Wiles [2010]), evolutionary science has been under essentially continuous social attack even since before Darwin’s explanation of evolution by natural selection became widely known in 1859 (Moore [1991]). And it remains a hotly-debated political topic, especially regarding its role in science education (Mooney and Nisbet [2005]; Wiles [2010]). Members of the general public are often unable to differentiate between political and scientific controversy, as despite scientific consensus, political leanings have been shown to influence acceptance of evolution (Allmon [2011]; Hawley et al. [2010]) which has led to lower rates of acceptance of evolution in the United States as compared to countries in which the issue is less politicized (Miller et al. [2006]). It has been suggested that acceptance of evolution may be linked to student achievement (Wiles and Alters [2011]), though some may disagree citing the differences between knowing, understanding, and believing (Smith [2009]; Southerland et al. [2001]).

Edward J. Larson has written a very thorough chronology of court cases related to creationism and evolution in the United States in Trial and Error: The American Controversy Over Creation and Evolution (Larson [2002]). Among the important events in this history were John Scopes’ conviction for teaching evolution, banned in Tennessee by the Butler Act; the subsequent rejection by the U. S. Supreme Court of the banning of evolutionary instruction in Epperson v. Arkansas; the downfall of ‘balanced treatment’ of so-called ‘creation science’ and evolution; and the federal overturning of Louisiana’s ‘Creationism Act’ , which forbade the teaching of evolution except when accompanied by instruction in ‘creation science’ , in Edwards v. Aguillard.

Evolution has become regarded as a cornerstone for education in biology, and is incorporated into the standards for grade school biology recommended by the National Research Council and the Next Generation Science Standards (National Research Council [1996]; NGSS Consortium Of Lead States [2013]). Evolution has long been considered to be an important part of scientific literacy (American Association for the Advancement of Science [1990, 1993]), and it is also considered to be integral in higher education in the biological sciences (Alters and Nelson [2002]).

The social controversy continued, however. Amid a growing wake of court decisions barring creationism, ‘creation science’ and other explicitly religious constructs from public school science classrooms, the creationist opponents to the teaching of evolution began to concoct a more ‘scientific’ sounding alternative to evolution that they called Intelligent Design (ID) (Pennock and Ruse [2009]). As with creation science, bills encouraging the inclusion of ID in curricula do so to help students ‘develop critical thinking skills’ by ‘teaching the controversy’ (Brumfiel [2005]; Mervis [2011]). ID advocacy groups have celebrated the passage of bills allowing teachers to present the ‘strengths and weaknesses’ of ‘controversial’ topics like evolution in two U.S. states, Louisiana and Tennessee, in the past several years (Thompson [2012]) despite opposition from such groups as the National Center for Science Education.

The evidence is clear, and the scientific community is unified in its assessment of the fact of evolution. Science educators are resolute in their insistence that evolution be taught as a foundational principle of the life sciences. So why, then, do students emerge from our education system largely unknowing and unaccepting of evolution to the point that the political controversy over the teaching of evolution has continued for generations?

There are a number of factors that are thought to affect students’ acceptance of evolution, which can be grouped into non-religious and religious factors (Alters and Alters [2001]; Wiles and Alters [2011]). Per Wiles and Alters ([2011]) and Wiles ([2014]) in which they are discussed in greater depth, they may include the following:

Non-religious factors

Scientific factors

o Overall knowledge of evolutionary theory

o Knowledge of evolutionary evidence

o Uncertainty about the origin of life

o Understanding of evolutionary mechanisms and patterns

o Understanding of the nature of science

Non-scientific factors

o Social and emotional factors (for example, personal relationships, authorities, fear, or discomfort with perceived implications of evolution)

o Critical thinking skills, epistemological views, and cognitive dispositions

o Demographic factors (for example, academic standing, political leanings)

Religious factors

Perception that religious belief and acceptance of evolution are mutually exclusive

Literal interpretation of scripture

Creationist convictions

Labeling of religious doctrine as scientific (for example, ‘creation science’ and ID)

A few studies have shown that presenting students with a direct comparison of the misconceptions about evolution that can result from these factors (or indeed be intentionally perpetuated by creationist groups) can lead to increased acceptance of evolution (Ingram and Nelson [2006]; Matthews [2001]; McKeachie et al. [2002]).

Several studies have suggested that increasing students’ understanding of the nature of science (NOS) may enhance their acceptance of evolution (Allmon [2011]; Dagher and BouJaoude [1997]; Rudolph and Stewart [1998]; Sinatra et al. [2003]; Smith [2009]; Southerland et al. [2001]). NOS describes the philosophy of science including how scientific knowledge is generated and how science progresses. Key concepts of NOS include viewing science as more than just the oversimplified, stepwise scientific method presented in many textbooks; the role of the scientific community in the generation of scientific knowledge; the theory laden nature of observation and experimentation; and the fact that scientific theories are durable while science itself is a self-correcting process (Grinnell [2009]). Increasing NOS understanding is important in science education in general, as evidenced by its inclusion in the national science education standards (National Research Council [1996]), but is predicted to increase acceptance of evolution as students learn about how evidence is considered and the role of consensus in the scientific community. Though many authors suggest that NOS understanding plays a role in the acceptance of evolution, the positive link between changes in NOS conceptions and attitudes towards evolution has, until this study, been poorly understood.

Climate change

While it was once contentious among scientists, the vast majority of scientists now agree on many aspects of global climate change (GCC): that it is occurring, that the changes we are observing are most likely due to human influence, and that the changing climate may have other effects such as rising sea levels and changes in the nitrogen cycle (National Research Council [2010]). Consensus crosses not only scientific and institutional borders, but political ones as well. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has produced a number of reports focusing not only on the strength of the science behind GCC, but also on GCC impacts, vulnerability, and mitigation (IPCC [2007], Stocker et al. [2013]). Consensus across so many scientific, political, and ideological borders is unprecedented and may speak to the importance of the issues associated with GCC.

Like evolution, GCC is a much more contentious issue politically than it is scientifically. GCC has been a common subject in national polls over the last 20 years (Nisbet and Myers [2007]), and these data have been used extensively to document how concern over GCC correlates with different demographic factors, especially whether respondents identify as democrats, republicans, or independents. GCC has been found to be extremely politicized (McCright [2010a]), and studies have shown that the gap in GCC concern between Democrats and Republicans has increased markedly over the last 10 years (Dunlap and McCright [2008]; McCright and Dunlap [2011b]). Conservative white men have been shown to be the most likely demographic to deny GCC (McCright and Dunlap [2011a]). Somewhat surprising is the presence of strong interaction effects between knowledge about climate change and political identification. That is, among Democrats, GCC concerns increase along with knowledge of GCC, but the same relationship in republicans is weak to negative (Hamilton [2011]). The politicization of GCC is most prevalent in the U.S., with cross-national surveys indicating that in most other industrialized nations the views on GCC are much more closely aligned with those of the scientific community (Dispensa and Brulle [2003]; Kvaloy et al. [2012]).

The political controversies around GCC are surely affecting the teaching of climate science in schools. Like evolution, GCC has been proposed as a central focus in science education because of the scientific consensus behind it coupled with the need for societal action to mitigate its effects (Sharma [2012]). This view is shared by many within the science education community including the National Association of Biology teachers who identify GCC as an environmental concept ‘particularly relevant to students’ everyday lives’ (National Association of Biology Teachers [2004]) and the National Association of Geoscience Teachers who recognize

-

(1)

that Earth’s climate is changing,

-

(2)

that present warming trends are largely the result of human activities, and

-

(3)

that teaching climate change science is a fundamental and integral part of earth science education (National Association of Geoscience Teachers [2008]).

And yet, GCC is second only to evolution in topics that educators are unlikely to bring up due to discomfort or fear of controversy (Reardon [2011]). Recognizing the need for action in defense of climate change education, the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), an organization well-known known for defending the teaching of evolution, added promotion and protection of the teaching of climate science to its mission. Because attacks on climate change, like those on evolution, rely on misrepresenting climate change denial as being scientifically rather than politically motivated, the NCSE and other groups are concerned that ‘teach the controversy’ bills will affect education on both issues (Mervis [2011]). Strategies for GCC education are still developing, perhaps because it is a much more recent concept than evolution (Cordero et al. [2008]; Manolas and Filho [2011]; Matkins and Bell [2007]; McNeill and Vaughn [2012]; National Research Council [2010]; Shepardson et al. [2012]; Svihla and Linn [2012]). The fact that many students and members of the public get most of their knowledge about GCC from the media is additionally problematic. Reporters often have difficulty differentiating between scientific and political controversy, and both evolution and climate change deniers often actively craft their arguments to appear scientific, thereby encouraging this confusion (Dispensa and Brulle [2003]). Thus, it has been suggested that training in media literacy, specifically how to critically analyze media coverage to determine sources, bias, and so on, should be an active pursuit in improving understanding and acceptance of GCC (Cooper [2011]).

For GCC, ‘acceptance’ is not a term that is commonly used in the literature (though denial is frequently used). The data on attitudes towards climate change are almost entirely from national surveys, which frame their questions as a sliding scale of concern. However, a number of demographic factors have been shown to correlate with views on GCC. These factors include;

Scientific factors

Knowledge about GCC (either measured or self-declared)

Non-scientific factors

Religiosity

Demographic factors

o Political leanings/Party identification

o Education level

o Gender (weak but significant correlation)

o Age

o Region of residence

(Borick and Rabe [2012]; Hamilton and Keim [2009]; Hamilton [2011]; Marquart-Pyatt et al. [2011]; McCright and Dunlap [2011a, 2011b]; McCright [2010a, 2010b]; Nisbet and Myers [2007]).

The abundance of correlations demonstrates that GCC is a very complex issue, with even regional variation in perceptions (Hamilton and Keim [2009]). Perhaps bizarrely, one study even found that the presence of healthy versus dead plants in the room in which the survey is administered had a significant effect on participants’ GCC concerns (Guéguen [2012]).

Perhaps the only study has directly linked NOS understanding and GCC revealed that after receiving explicit instruction in both GCC and NOS, education students showed increased understanding of both (Matkins and Bell [2007]). The authors concluded that explicit NOS instruction had a positive effect on NOS understanding as well as complex issues of GCC (Matkins and Bell [2007]), but given the nature of the study, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to establish NOS instruction as the causal agent of GCC understanding rather than the extensive instruction in GCC. A number of the teaching strategies that have been suggested involve some aspect of NOS, whether it be teaching students the ability to differentiate between scientific and non-scientific items in the media (Cooper [2011]) or teaching about how research programs on GCC are put together, including how models are developed (Manolas and Filho [2011]).

NOS understanding may play a role in forming students’ opinions on GCC, but further research on the topic is clearly warranted. Herein, we present our exploration of this problem as well as how attitudes toward the topic of evolution compare among a sample of university students in an introductory biology course.

Methods

Although other extant tools for assessing NOS conceptions provide much more robust measurements (Bell and Lederman [2003]; Abd-El-Khalick [2001]; Lederman [1999]), they are decidedly more labor-intensive to score and not easily implemented via the online tools and under the Institutional Review Board guidelines approved for this study. Additionally, these tools do not provide the quantitative output necessary for large-scale statistical comparison. Hence, we chose to measure student conceptions of NOS with the Thinking about Science Survey Instrument (TSSI) (Coburn [2000]). The TSSI provided numeric scores for student agreement with nine aspects of the modern model of science. In our final analyses, the sum total of these scores proved to have the most explanatory value, though the score for the ‘epistemology’ category was a close second. The Measure of Acceptance of the Theory of Evolution (MATE) was employed to assess students attitudes toward evolution, as it has been validated for measuring acceptance of evolution among various populations (Rutledge and Sadler [2007]; Rutledge and Warden [1999]), and it has also been used to measure longitudinal change in students’ attitudes toward evolution (Wiles and Alters [2011]). Since a validated tool for measuring attitudes towards GCC did not exist at the time of this study, student attitudes were measured using questions from national opinion polls (Borick and Rabe [2012]; Hamilton and Keim [2009]; Hamilton [2011]; Leiserowitz et al. [2012]; Nisbet and Myers [2007]). Demographic questions were generated to measure various factors either shown or suspected to affect attitude towards evolution or GCC. See Additional file 1 for the full list of GCC and demographic questions.

Each survey was administered to a large sample of introductory biology students (N = 620) at a large private university in the northeastern US at the beginning and end of the course (with the exception of demographics, which were administered once near the middle of the semester). Some additional questions were added at the end of the course to determine whether important demographic shifts may have occurred (for example, in religious practice or political views) since the previous reporting of these factors. Other variables used in the analysis included a measure of knowledge of evolutionary science (total score on a selection of questions on evolution from the final exam), a measure of knowledge of GCC (total score on a selection of questions on GCC from a quiz produced by NASA ([National Aeronautics and Space Administration n.d.])), and a measure of success in the course (the numeric final grade in the biology course).

In order to account for the fact that those students with high scores on the pre-course surveys would have little room for increase, normalized gain was calculated for a number of items, including TSSI total score and MATE score. Normalized gain is calculated by dividing differences in pretest and post-test values by the difference between the pretest value and the maximum possible score, and is frequently used in pretest/post-test analyses (Hake [2002]). Principle components analysis (PCA) was used to determine which variables accounted for the majority of variation. Paired t-tests were used to analyze pre-to-post-course differences for individual variables. Finally, ANOVA, along with correlation tests, were used to test for significant correlations, while ANCOVA was used to test for interaction effects with demographic factors.

Student name and ID numbers were removed and replaced with a numeric identifier so that pre- and post-course responses could be paired while maintaining anonymity. The protocols used for this study were approved by the university's Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results and discussion

From the pre-course surveys, it was clear that this population was different from the U.S. general public. Upwards of 60% of respondents scored in the ‘high’ or ‘very high’ range of evolution acceptance, while most polls indicate that less than half of the U.S. public believe in evolution. For GCC, results were similar. Nearly 95% of respondents said they believe GCC is occurring (as compared to 66% of the U.S. public). For this reason, for analysis of attitudes towards GCC, we focused on students’ levels of personal concern regarding GCC rather than acceptance. Responses on this item were considerably more varied, with about 44% of respondents reporting that the issue was ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ important, while about 16% reported that the issue was ‘not too’ or ‘not at all’ important. In the U.S. public, 20% said the issue was ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ important, while 39% rated GCC as ‘not too’ or ‘not at all’ important. It is important to note that while the percentages of students in the low end is low, the overall sample is quite large (N = 620), such that the number of students in these lower tiers is actually larger than the entire sample size of many similar studies (for example, N = 205 respondents with acceptance of evolution ranging from ‘very low’ to ‘moderate’).

Changes in acceptance of evolution are significantly positively correlated with changes in NOS conceptions, with religiosity as the main demographic factor affecting acceptance. As shown in Figure 1, normalized gains of MATE score and total TSSI score had a correlation of 0.35, and were highly significant (P <0.001). Both pre-course and post-course MATE scores were significantly negatively correlated with religiosity (respondents’ Likert-scale responses to the question ‘how active do you consider yourself to be in the practice of your religious preference?’). The post-course relationship, shown in Figure 2, was more weakly correlated (r = −0.2) than the pre-course relationship (r = −0.32), but no less significant (P <0.0001). There was a very small and weakly significant positive correlation between gains in evolution acceptance and reporting an increase in religious activity during the span of the course (r = 0.08, P = 0.08), which is particularly interesting since the lack of a negative correlation provides evidence against the claim, oft repeated by creationists, that increasing acceptance of evolution leads to decreasing religious belief or activity. As illustrated by Figure 3, post-course evolution acceptance was also significantly positively correlated with knowledge of evolutionary science (r = 0.35, P <0.0001), which supports the findings of previous research on this subject (Wiles and Alters [2011]).

The relationship between changes in students’ NOS conceptions and evolutionary attitudes. Changes in NOS conceptions, as measured by the normalized gains of total scores on the TSSI, are significantly positively correlated with changes in attitudes towards evolution, measured by normalized gains of total scores on the MATE tool. The value of r indicated in the figure (0.355), is Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the two variables.

The relationship between students’ post-course evolutionary attitudes and religiosity. Student attitudes towards evolution, as measured by their post-course total score on the MATE tool, are negatively correlated with religiosity, here a Likert-scale response to the question ‘how active would you say you are in the practice of your religious preference?’ This factor has four levels, ranging from zero (not active) to three (very active). The value of r indicated in the figure (−0.2), is Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the two variables.

The relationship between students’ post-course evolutionary attitudes and knowledge of evolutionary science. Student attitudes towards evolution, as measured by their post-course total score on the MATE tool, are positively correlated with knowledge of evolutionary science. The latter was measured using a subset of questions from the course final exam which pertained directly to the science of evolution. The value of r indicated in the figure (0.35), is Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the two variables.

Changes in GCC attitudes also correlate with changes in NOS conceptions. At an alpha of 0.1, changes in personal importance of the issue of climate change are weakly positively correlated with normalized gains in TSSI total score. This comparison is shown in Figure 4, with P = 0.065 and r = 0.087. Additionally, respondents’ scientific view of GCC (a composite of responses to two questions that measured respondents’ awareness of the views of the scientific community on GCC) were not significantly correlated with NOS conceptions in the pre-course surveys, but were correlated in post-course surveys, with r = 0.118 with P <0.01, which may be linked to NOS conceptions having to do with scientific consensus and the treatment of evidence. Interestingly, knowledge about GCC was not significantly correlated with attitudes towards GCC.

Relationship between changes in students’ attitudes towards GCC and conceptions about NOS. At an alpha of 0.1 1, changes in how important the issue of GCC was to students had a weak positive correlation with changes in nature of science conceptions, measured by the normalized gains of total scores on the TSSI. The value of r indicated in the figure (0.087), is Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the two variables.

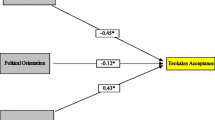

In both pre- and post-course surveys, personal importance of GCC is most strongly correlated with political leanings, that is, negatively correlated with conservatism. Interestingly, that correlation does become weaker, though no less significant, from the first to second survey; pre-course r = −0.215 with P <0.0001 while post-course, r = −0. 171 with P <0.0001. The trend is also present when examining political party affiliations. As shown in Figure 5, identifying as a democrat is positively correlated with GCC importance (r = 0.113, P <0.01), while identifying as a republican is negatively correlated with GCC importance (r = −0.11, P <0.05).

The relationship between students’ political party identification and personal importance of GCC. In this figure, blue circles and the blue positive trend line represent the relationship between post-course personal importance of GCC and identification as a Democrat. Red triangles and the red negative trend line represent the relationship between post-course personal importance of GCC and identification as a Republican. The sizes of the symbols increase with increasing number of overlapping data points so that their distribution can be more easily visualized. Here the trends are essentially opposite for students identifying with the two parties, with a positive Pearson’s correlation coefficient (0.128) for Democrats, and a negative one (−0.109) for Republicans. It is important to note, however, that the two variables were more weakly correlated, for both Democrats and Republicans, when comparing post-course attitudes towards climate change rather than pre-course attitudes.

Conclusions

In this study, changes in evolution acceptance and changes in attitudes towards GCC do correlate positively with changes in NOS conceptions. These findings support the hypothesis that a better understanding of the modern model of science may lead to changes in attitudes towards politically contentious ideas that are not scientifically contentious. However, the data indicate that correlations differ between evolution and climate change. Of all the measured variables in this study, measures of political views were most highly correlated with attitudes towards GCC. More conservative political views, especially fiscal conservatism, correlated negatively with personal importance of the issue of climate change. Broken down among party lines, correlations between party identification and importance of GCC were almost exactly opposite (for republicans, r = −0.11 while for democrats r = +0.13). Interestingly, party leanings do NOT significantly correlate with changes in GCC attitudes, which could indicate a lack of large enough changes in GCC attitudes to measure. A paired t-test indicates a mean difference of just 0.06 between pre- and post-course measurements for a factor with five levels. The lack of difference is not surprising, given the fact that there is considerably less direct instruction on GCC in the course than there is on evolution.

Not only were GCC importance and concern most strongly correlated with political views, but of the GCC deniers in our sample, over two-thirds identified politically as fiscal conservatives. Unsurprisingly, evolution rejection was most strongly correlated with religious factors. However, GCC deniers in this study tended not to be highly religious or affiliated with conservative denominations. These results are consistent with data from a Pew Research Center ([2009]) poll which found that the strongest predictor of climate change denial is political affiliation, with political conservatives being more likely to deny GCC than other groups. The same poll also found that religious conservatism, whether measured by denominational affiliation or degree of religiosity, was the strongest correlate of evolution denial. Religious conservatism does not map perfectly onto political conservatism, but there is certainly an area of overlap known as the ‘religious right’. Similarly, rejection of evolution does not always predict rejection of GCC. Figure 6 illustrates this, as the ‘zone of denial’ shifts from religious to political conservatism as it moves from rejection of evolution to rejection of GCC.

The shifting zone of science denial. Political conservatives and religious conservatives are represented separately in this Venn diagram, with the overlap between them identified as the ‘religious right’. The zone of denial shifts from being driven primarily by religious ideology with regard to evolution to being predominately influenced by political ideology for climate change.

The lack of correlation between changes in evolution acceptance and changes in religious activity counters the idea that belief in evolution and religion are mutually exclusive, one of the ‘pillars of creationism’ according to the National Center for Science Education (National Center for Science Education [2008]). That is to say, becoming more accepting of evolution does not necessarily mean becoming less religiously active, or vice versa. Actually, a very slight positive relationship between the two was measured among this population.

This study has various important implications. First, giving students a good conception of the modern NOS may lead to views that are more in line with those of the scientific community. Of course, further research is required to establish the direction of causation, but it is difficult to imagine how becoming more concerned about climate change could cause a more scientific epistemology or a better understanding of scientific methodology. Second, while evolution is thought of as a politically contentious topic, as is the case currently in Louisiana, attitudes towards GCC are much more related to political views in this study population. The fact that these correlations do decrease over the span of the course, however, is heartening. A greater emphasis on GCC (and NOS) may even lead to the disappearance of this correlation entirely. Finally, this study represents the first concrete evidence of a linkage between acceptance of evolution and attitudes towards GCC, that is, NOS conceptions.

Future research on this topic should involve multiple institutions, comparing universities of different types, sizes, and geographic locations. More robust measures of NOS conceptions should be employed where possible, and qualitative methods such as interviews could be used to help determine the direction of causation for the various correlations discovered in this study. Students with large gains in evolution acceptance should be interviewed to determine how those changes came about.

Authors’ information

BEC is pursuing a Ph.D. in college science teaching at Syracuse University. JRW is a biology professor at Syracuse University and holds secondary appointments in the Syracuse University departments of Earth Science and Science Teaching.

Additional file

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance:

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance:

- GCC:

-

Global climate change:

- ID:

-

Intelligent Design:

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board:

- MATE:

-

Measure of acceptance of the theory of evolution:

- NASA:

-

National Aeronautics and Space Administration:

- NOS:

-

Nature of science:

- PCA:

-

Principle components analysis:

- TSSI:

-

Thinking about science survey instrument:

References

Allmon WD: Why don’t people think evolution is true? Implications for teaching, in and out of the classroom. Evolution: Education and Outreach 2011, 4(4):648–665.

Alters BJ, Nelson CE: Perspective: teaching evolution in higher education. Evolution 2002, 56(10):1891–1901.

Alters BJ, Alters S: Defending Evolution in the Classroom: A Guide to the Creation/evolution Controversy. Jones & Bartlett Learning, Sudbury, MA; 2001.

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (1990). Science for All Americans. In (Ed.), Science for All Americans Chapter 1: The Nature of Science. New York: Oxford University Press. . Accessed 28 May 2012., [http://www.project2061.org/publications/sfaa/online/chap1.htm]

Benchmarks for Scientific Literacy: A Project 2061 Report. Oxford University Press, New York; 1993.

American Institute of Biological Sciences (1994). AIBS Board Resolution on Evolution Education. http://www.aibs.org/position-statements/19941001_evolution_resolution.html. Accessed 23 August 2013

Bell RL, Lederman NG: Understandings of the nature of science and decision making on science and technology based issues. Science Education 2003, 87(3):352–377. 10.1002/sce.10063

Borick C, Rabe B: Fall 2011 National Survey of American Public Opinion on Climate Change. Issues in Governance Studies 45. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC; 2012.

Brumfiel G: Intelligent design: who has designs on your students’ minds? Nature 2005, 434(7037):1062–1065. 10.1038/4341062a

Coburn W: The Thinking About Science Survey Instrument. Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI; 2000.

Cooper CB: Media literacy as a key strategy toward improving public acceptance of climate change science. BioScience 2011, 61(3):231–237. 10.1525/bio.2011.61.3.8

Cordero EC, Todd AM, Abellera D: Climate change education and the ecological footprint. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2008, 89(6):865–872. 10.1175/2007BAMS2432.1

Dagher ZR, BouJaoude S: Scientific views and religious beliefs of college students: the case of biological evolution. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 1997, 34(5):429–445. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199705)34:5<429::AID-TEA2>3.0.CO;2-S

Dispensa JM, Brulle RJ: Media’s social construction of environmental issues: focus on global warming–a comparative study. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 2003, 23(10):74–105. 10.1108/01443330310790327

Dobzhansky T: Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. The American Biology Teacher 1973, 35: 125–129. 10.2307/4444260

Dunlap RE, McCright AM: A widening gap: republican and democratic views on climate change. Environment 2008, 50(5):26–35. 10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35

Abd-El-Khalick F: Embedding nature of science instruction in preservice elementary science courses: abandoning scientism, but. Journal of Science Teacher Education 2001, 12(3):215–233. 10.1023/A:1016720417219

Eldredge N: Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, NY; 2005.

Gould SJ: Evolution as fact and theory. Discover 1981, 2(5):34–37.

Grinnell F: Everyday Practice of Science: Where Intuition and Passion Meet Objectivity and Logic. Oxford University Press, New York; 2009.

Guéguen N: Dead indoor plants strengthen belief in global warming. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2012, 32(2):173–177. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.12.002

Hake RR: Relationship of Individual Student Normalized Learning Gains in Mechanics with Gender, High-School Physics, and Pretest Scores on Mathematics and Spatial Visualization. Physics Education Research Conference, Boise, ID; 2002.

Hamilton LC: Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change 2011, 104(2):231–242. 10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8

Hamilton LC, Keim BD: Regional variation in perceptions about climate change. International Journal of Climatology 2009, 29(15):2348–2352. 10.1002/joc.1930

Hawley PH, Short SD, McCune LA, Osman MR, Little TD: What’s the matter with Kansas?: The Development and Confirmation of the Evolutionary Attitudes and Literacy Survey (EALS). Evolution: Education and Outreach 2010, 4(1):117–132.

Ingram EL, Nelson CE: Relationship between achievement and students’ acceptance of evolution or creation in an upper-level evolution course. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 2006, 43(1):7–24. 10.1002/tea.20093

Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva; 2007.

Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY; 2013.

Kvaloy B, Finseraas H, Listhaug O: The publics’ concern for global warming: a cross-national study of 47 countries. Journal of Peace Research 2012, 49(1):11–22. 10.1177/0022343311425841

Larson EJ: Trial and Error: The American Controversy Over Creation and Evolution: The American Controversy Over Creation and Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 2002.

Lederman NG: Teachers’ understanding of the nature of science and classroom practice: factors that facilitate or impede the relationship. Journal of research in science teaching 1999, 36(8):916–929. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199910)36:8<916::AID-TEA2>3.0.CO;2-A

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Hmielowski JD: Climate Change in the American Mind: Americans’ Global Warming Beliefs and Attitudes in March 2012. Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. Yale University and George Mason University, New Haven, CT; 2012.

Manolas E, Filho WL: The use of cooperative learning in dispelling student misconceptions on climate change. Journal of Baltic Science Education 2011, 10(3):168–182.

Marquart-Pyatt ST, Shwom RL, Dietz T, Dunlap RE, Kaplowitz SA, McCright AM, Zahran S: Understanding public opinion on climate change: a call for research. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 2011, 53(4):38–42.

Matkins J, Bell R: Awakening the scientist inside: global climate change and the nature of science in an elementary science methods course. Journal of Science Teacher Education 2007, 18(2):137–163. 10.1007/s10972-006-9033-4

Matthews D: Effect of a curriculum containing creation stories on attitudes about evolution. The American Biology Teacher 2001, 63(6):404–409. 10.1662/0002-7685(2001)063[0404:EOACCC]2.0.CO;2

McCright AM: Political orientation moderates Americans’ beliefs and concern about climate change. Climatic Change 2010, 104(2):243–253. 10.1007/s10584-010-9946-y

McCright AM: The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Population and Environment 2010, 32(1):66–87. 10.1007/s11111-010-0113-1

McCright AM, Dunlap RE: Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change 2011, 21(4):1163–1172. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003

McCright AM, Dunlap RE: The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociological Quarterly 2011, 52(2):155–194. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

McKeachie WJ, Lin Y-G, Strayer J: Creationist vs Evolutionary beliefs: effects on learning biology. The American Biology Teacher 2002, 64(3):189–192.

McNeill K, Vaughn M: Urban High School Students’ Critical Science Agency: conceptual understandings and environmental actions around climate change. Research in Science Education 2012, 42(2):373–399. 10.1007/s11165-010-9202-5

Mervis J: Tennessee House Bill opens door to challenges to evolution, climate change. Science 2011, 332(6027):295–295. 10.1126/science.332.6027.295

Miller JD, Scott EC, Okamoto S: Public acceptance of evolution. Science 2006, 313(5788):765. 10.1126/science.1126746

Mooney C, Nisbet MC: Undoing Darwin: when the coverage of evolution shifts to the political and opinion pages, the scientific context falls away. (cover Story). Columbia Journalism Review 2005, 44(3):30–39.

Moore J: Deconstructing Darwinism: The Politics of Evolution in the 1860 s. Journal of the History of Biology 1991, 24(3):353–408. 10.1007/BF00156318

National Aeronautics and Space Administration n.d. Climate Change: Interactive Global Temperature Quiz. http://climate.nasa.gov/interactives/quiz_global_temp/quiz). Accessed 15 August 2013

National Association of Biology Teachers. (2004). NABT Institution. Reston, VA. NABT. . Accessed 15 August 2013., [http://www.nabt.org/websites/institution/index.php?p=96]

Teaching Climate Change. NAGT, Northfield, MN; 2008.

The Pillars of Creationism. NCSE, Oakland, CA; 2008.

National Science Education Standards. National Academic Press, Washington D.C; 1996.

Advancing the Science of Climate Change. The National Academies Press, Washington D.C; 2010.

Nisbet MC, Myers T: The polls–trends twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opinion Quarterly 2007, 71(3):444–470. 10.1093/poq/nfm031

Next Generation Science Standards: By States, for States. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.; 2013.

But Is It Science? The Philosophical Question in the Creation/Evolution Controversy. Prometheus Books, Amherst, NY; 2009.

Reardon S: Climate change sparks battles in classroom. Science 2011, 333(6043):688–689. 10.1126/science.333.6043.688

Rudolph JL, Stewart J: Evolution and the nature of science: on the historical discord and its implications for education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 1998, 35(10):1069–1089. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199812)35:10<1069::AID-TEA2>3.0.CO;2-A

Rutledge ML, Warden MA: The development and validation of the measure of acceptance of the theory of evolution instrument. School Science and Mathematics 1999, 99(1):13–18. 10.1111/j.1949-8594.1999.tb17441.x

Rutledge ML, Sadler KC: Reliability of the Measure of Acceptance of the Theory of Evolution (MATE) Instrument with University Students. The American Biology Teacher 2007, 69(6):332–335. 10.1662/0002-7685(2007)69[332:ROTMOA]2.0.CO;2

Scott EC: Evolution Vs. Creationism: An Introduction. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA; 2004.

Sharma A: Global Climate Change: what has science education got to do with it? Science & Education 2012, 21(1):33–53. 10.1007/s11191-011-9372-1

Shepardson DP, Niyogi D, Roychoudhury A, Hirsch A: Conceptualizing climate change in the context of a climate system: implications for climate and environmental education. Environmental Education Research 2012, 18(3):323–352. 10.1080/13504622.2011.622839

Sinatra GM, Southerland SA, McConaughy F, Demastes JW: Intentions and beliefs in students’ understanding and acceptance of biological evolution. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 2003, 40(5):510–528. 10.1002/tea.10087

Smith MU: Current Status of Research in Teaching and Learning Evolution: I. philosophical/epistemological issues. Science & Education 2009, 19(6–8):523–538.

Southerland SA, Sinatra GM, Matthews MR: Belief, knowledge, and science education. Educational Psychology Review 2001, 13(4):325–351. 10.1023/A:1011913813847

Svihla V, Linn MC: A design-based approach to fostering understanding of global climate change. International Journal of Science Education 2012, 34(5):651–676. 10.1080/09500693.2011.597453

Scientific Achievements Less Prominent Than a Decade Ago. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C; 2009.

Thompson, H (2012). Tennessee ‘monkey Bill’ Becomes Law. Nature 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature.2012.10423

Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB: Campbell Biology. Pearson Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco, CA; 2011.

Wiles JR: Overwhelming scientific confidence in evolution and its centrality in science education-and the public disconnect. The Science Education Review 2010, 9(1):18–27.

Wiles, JR. (2014). Gifted Students' Perceptions of their Acceptance of Evolution, Changes in Acceptance, and Factors Involved Therein. Evolution: Education and Outreach. doi: 10.1186/s12052–014–0004–5

Wiles JR, Alters BJ: Effects of an educational experience incorporating an inventory of factors potentially influencing student acceptance of biological evolution. International Journal of Science Education 2011, 33(18):2559–2585. 10.1080/09500693.2011.565522

Acknowledgements

The authors offer sincere thanks to Bev Werner for her help with the logistics of electronic administration of surveys as well as anonymizing them. BEC thanks Caitlin Conn for her feedback on drafts of the manuscript. The authors also thank Eugenie Scott for her original conception of the shifting zone of science denial among conservatives, anonymous reviewers for helpful editorial comments, and Josh Rosenau for help with data processing and key information from public opinion polls.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BEC collected and analyzed survey data, wrote demographic questions, generated figures, and drafted the manuscript. JRW helped conceptualize and design the study, provided numerous resources for data collection, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, B.E., Wiles, J.R. Scientific consensus and social controversy: exploring relationships between students’ conceptions of the nature of science, biological evolution, and global climate change. Evo Edu Outreach 7, 6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-014-0006-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-014-0006-3