Abstract

Following intravenous administration, vancomycin is poorly metabolized and is mainly excreted unchanged in urine. Total body clearance is thus dependent on the kidney, and is correlated with glomerular filtration rate and creatinine clearance. Accumulation of vancomycin in patients with renal insufficiency may therefore occur, and this may lead to toxic side effects if dosage is not modified according to the degree of renal failure. Furthermore, vancomycin easily diffuses through dialysis membranes. The aim of the present review is to establish guidelines for handling this drug in such patients. We indicate how and when plasma concentrations of vancomycin should be determined in dialysis patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic that used in the treatment of severe infections with pathogens such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp. Following intravenous administration, vancomycin is poorly metabolized and is mainly excreted unchanged in urine. Total body clearance is thus dependent on the kidney, and is correlated with glomerular filtration rate and creatinine clearance [1]. Elimination of the agent is slowed in patients with renal insufficiency. Accumulation of vancomycin may thus occur and may lead to toxic side effects if the dosage is not modified in accordance with the degree of renal failure. Furthermore, vancomycin has a low volume of distribution (0.6 l/kg), a low protein-bound fraction (50%) and a low molecular weight (1449 Da) [2], suggesting that it can easily diffuse through dialysis membranes.

We synthesized results from studies on vancomycin dialyzability in different types of membranes and with different dialysis techniques (intermittent and continuous). The aim of the present review is not to detail the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in dialysis patients but to establish guidelines for handling this drug in such patients. The fundamental principle for the use of vancomycin in dialysis patients is that the drug should only be administered when the plasma concentration is too low to be effective. However, guidelines for appropriate plasma sampling schedules are not available. We therefore indicate how and when plasma concentrations of vancomycin should be determined in dialysis patients. Finally, administration technique is not discussed here because the ideal technique is not clearly established [3].

Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in renal impairment

Renal excretion of vancomycin is altered in patients with renal insufficiency. The manufacturer of Vancocin® (Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA; reviewed April 2000) has reported that, in anephric patients, the average vancomycin elimination half-life is 7.5 days, whereas it is 4–6 hours in patients with normal renal function. It has also been reported that total body clearance of vancomycin is correlated with creatinine clearance in patients with altered renal function [4]. Although it is clear that renal clearance of vancomycin is decreased in patients with renal failure, it has also been suggested that nonrenal clearance of vancomycin, which usually accounts for approximately 30% (40 ml/min) of total clearance in patients with normal renal function, is reduced to as low as 5–6 ml/min in patients with terminal renal insufficiency [1,5]. While the mechanisms of this reduction are still unidentified, inhibition of vancomycin metabolism by uraemic toxins is suspected [6].

Because both renal and nonrenal vancomycin clearances are reduced in patients with impaired renal function, accumulation of unchanged active drug in plasma is likely to occur. For this reason, application of existing nomograms or equations for adjustment of vancomycin dosage in patients with renal impairment [1,5,7] should be accompanied by monitoring of plasma vancomycin levels [8,9]. These nomograms or equations were established on the basis of decline in renal clearance, and do not take into account the decline in nonrenal clearance. Therefore, their application in patients with compromised renal function may result in an insufficient reduction in dose and may lead to toxicity. It has been suggested that a vancomycin plasma concentration of 80 μg/ml would be a reliable level for the toxicity threshold [10]. However, it should be pointed out that the toxic serum level of vancomycin has not yet been precisely determined, and serum concentrations of vancomycin as high as 60–70 μg/ml may also be toxic in some patients, depending on the particular clinical situation or associated drugs. Furthermore, it has recently been shown that nephrotoxicity might be a marker of failure of vancomycin treatment [3].

The major adverse effects of vancomycin are ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. The relationship between vancomycin-induced ototoxicity and plasma concentration of the drug (peak or trough levels) is still undergoing investigation. However, vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity has been clearly related to drug plasma concentrations. In a study involving 198 cancer patients administered vancomycin for treatment of Gram-positive bacteraemia, Kralovicova and coworkers [11] retrospectively compared occurrence of vancomycin-related nephrotoxicity with vancomycin trough serum levels. Trough vancomycin levels greater than 15 μg/ml were associated with significantly more nephrotoxicity. Those investigators concluded that maintenance vancomycin doses should be administered according to the value of the trough level (i.e. maintaining the trough level <15 μg/ml).

In patients with terminal renal insufficiency undergoing haemodialysis, whether intermittent or continuous, and receiving vancomycin therapy, elimination of the drug during the procedure must be considered when establishing the dosing schedule.

Vancomycin in intermittent haemodialysis (chronic haemodialysis)

Several studies have been reported (Table 1). The two major elements that can be concluded from analysis of these studies are as follows: vancomycin is not significantly dialyzable when haemodialysis is performed using a low flux membrane such as cuprophan; and vancomycin is significantly dialyzable when haemodialysis is performed using a high flux membrane such as polysulfone, polyacrylonitrile and poly-methylmethacrylate.

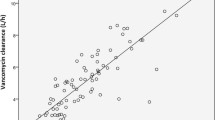

Studies of the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in patients undergoing haemodialysis with high flux membranes demonstrated that there is a rebound in vancomycin plasma concentrations at the end of the session. The plasma profile of vancomycin concentrations versus time indicates that concentrations decrease dramatically during the session and then increase when the session is stopped for 3–6 hours (Fig. 1). This rebound may result from drug recirculation from plasma protein binding sites. Recirculation from peripheral compartments is less likely to occur because of the low vancomycin volume of distribution, indicating that the drug remains mainly in plasma. This rebound may be clinically significant, and it must be taken into account when determining vancomycin trough levels. Subsequently, it is recommended that determination of vancomycin trough levels in patients undergoing chronic haemodialysis should be performed before the haemodialysis session (Table 2).

Vancomycin pharmacokinetic profile during chronic haemodialysis: evidence for a postsession rebound in plasma concentration. Reproduced with permission from Welage et al. [22].

Vancomycin in continuous haemodialysis

Continuous renal replacement therapy increases total body clearance of vancomycin. However, quantification of vancomycin removal is difficult to estimate, and it is thus also recommended that plasma levels of the drug be monitored.

When a continuous technique is used, there is no rebound in vancomycin plasma concentration. Total body clearance of vancomycin is almost constant, and determination of trough levels may be performed at any time while continuous haemodialysis is being performed (Table 2). However, if dialysis is stopped and if vancomycin treatment must be continued, then the plasma concentration of vancomycin 4–6 hours after stopping haemodialysis should be determined before any readministration of the drug (Table 2).

Conclusion

Vancomycin is effectively removed when haemodialysis is performed with high flux membranes. Maintenance doses should be administered according to the plasma trough levels, as determined before the session when the patient is on chronic intermittent haemodialysis, at any time for continuous haemodialysis, and 6 hours after the end of haemodialysis when continuous therapy is stopped and vancomycin treatment is continued.

Vancomycin therapy is widely used in patients with decreased renal function, and serum levels of this agent must be closely monitored in such patients in order to avoid toxicity and subtherapeutic levels, in particular because emergence of resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics has been noted [12].

References

Moellering RC Jr, Krogstad DJ, Greenblatt DJ: Vancomycin therapy in patients with impaired renal function: a nomogram for dosage. Ann Intern Med 1981, 94: 343-346.

Dollery C: Vancomycin. In Therapeutic Drugs, 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999, V6-V10.

Wysocki M, Delatour F, Faurisson F, Rauss A, Pean Y, Misset B, Thomas F, Timsit JF, Similowski T, Mentec H, Mier L, Dreyfuss D: Continuous versus intermittent infusion of vancomycin in severe Staphylococcal infections : prospective multicenter randomized study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45: 2460-2467. 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2460-2467.2001

Nielsen HE, Hansen HE, Korsager B, Skov PE: Renal excretion of vancomycin in kidney disease. Acta Med Scand 1975, 197: 261-264.

Matzke GR, McGory RW, Halstenson CE, Keane WF: Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in patients with various degrees of renal function. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1984, 25: 433-437.

Macias WL, Mueller BA, Scarim SK: Vancomycin pharmacoki-netics in acute renal failure: preservation of nonrenal clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1991, 50: 688-694.

Lake KD, Peterson CD: A simplified dosing method for initiating vancomycin therapy. Pharmacotherapy 1985, 5: 640-644.

Andres I, Lopez R, Pou L, Pinol F, Pascual C: Vancomycin monitoring: one or two serum levels? Ther Drug Monit 1997, 19: 614-619. 10.1097/00007691-199712000-00002

Mulhern JG, Braden GL, O'Shea MH, Madden RL, Lipkowitz GS, Germain MJ: Trough serum vancomycin levels predict the relapse of gram-positive peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1995, 25: 611-615.

Bailie GR, Neal D: Vancomycin ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. A review. Med Toxicol 1988, 3: 376-386.

Kralovicova K, Spanik S, Halko J, Netriova J, Studena-Mrazova M, Novotny J, Grausova S, Koren P, Krupova I, Demitrovicova A, Kukuckova E, Krcmery V Jr: Do vancomycin serum levels predict failures of vancomycin therapy or nephrotoxicity incancer patients? J Chemother 1997, 9: 420-426.

Smith TL, Pearson ML, Wilcox KR, Cruz C, Lancaster MV, Robinson-Dunn B, Tenover FC, Zervos MJ, Band JD, White E, Jarvis WR: Emergence of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus . N Engl J Med 1999, 340: 493-501. 10.1056/NEJM199902183400701

Bellomo R, Ernest D, Parkin G, Boyce N: Clearance of vancomycin during continuous arteriovenous hemodiafiltration. Crit Care Med 1990, 18: 181-183.

Joy MS, Matzke GR, Frye RF, Palevsky PM: Determinants of vancomycin clearance by continuous venovenous hemofiltration and continuous venovenous hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1998, 31: 1019-1027.

Alwakeel J, Najjar TA, al-Yamani MJ, Huraib S, al-Haider A, Abuaisha H: Comparison of the effects of three haemodialysis membranes on vancomycin disposition. Int Urol Nephrol 1994, 26: 223-228.

Foote EF, Dreitlein WB, Steward CA, Kapoian T, Walker JA, Sherman RA: Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin when administered during high flux hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol 1998, 50: 51-55.

Lanese DM, Alfrey PS, Molitoris BA: Markedly increased clearance of vancomycin during hemodialysis using polysulfone dialysers. Kidney Int 1989, 35: 1409-1412.

Pollard TA, Lampasona V, Akkerman S, Tom K, Hooks MA, Mullins RE, Maroni BJ: Vancomycin redistribution: dosing recommendations following high-flux hemodialysis. Kidney Int 1994, 45: 232-237.

Schaedeli F, Uehlinger DE: Urea kinetics and dialysis treatment time predict vancomycin elimination during high-flux hemodialysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998, 63: 26-38.

Torras J, Cao C, Rivas MC, Cano M, Fernandez E, Montoliu J: Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in patients undergoing hemodialysis with polyacrylonitrile. Clin Nephrol 1991, 36: 35-41.

Touchette MA, Patel RV, Anandan JV, Dumler F, Zarowitz BJ: Vancomycin removal by high-flux polysulfone hemodialysis membranes in critically ill patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1995, 26: 469-474.

Welage LS, Mason NA, Hoffman EJ, Odeh RM, Dombrouski J, Patel JA, Swartz RD: Influence of cellulose triacetate hemodialyzers on vancomycin pharmacokinetics. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995, 6: 1284-1290.

Zoer J, Schrander-van der Meer AM, van Dorp WT: Dosage recommendation of vancomycin during haemodialysis with highly permeable membranes. Pharm World Sci 1997, 19: 191-196. 10.1023/A:1008600104232

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Launay-Vacher, V., Izzedine, H., Mercadal, L. et al. Clinical review: Use of vancomycin in haemodialysis patients. Crit Care 6, 313 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc1516

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc1516