Abstract

Background

The BIG score (Admission base deficit (B), International normalized ratio (I), andGlasgow Coma Scale (G)) has been shown to predict mortality on admission inpediatric trauma patients. The objective of this study was to assess itsperformance in predicting mortality in an adult trauma population, and to compareit with the existing Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) and probability ofsurvival (PS09) score.

Materials and methods

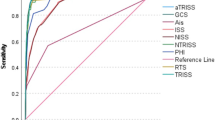

A retrospective analysis using data collected between 2005 and 2010 from seventrauma centers and registries in Europe and the United States of America wasperformed. We compared the BIG score with TRISS and PS09 scores in a population ofblunt and penetrating trauma patients. We then assessed the discrimination abilityof all scores via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and compared theexpected mortality rate (precision) of all scores with the observed mortalityrate.

Results

In total, 12,206 datasets were retrieved to validate the BIG score. The mean ISSwas 15 ± 11, and the mean 30-day mortality rate was 4.8%. With an AUROC of0.892 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.879 to 0.906), the BIG score performed wellin an adult population. TRISS had an area under ROC (AUROC) of 0.922 (0.913 to0.932) and the PS09 score of 0.825 (0.915 to 0.934). On a penetrating-traumapopulation, the BIG score had an AUROC result of 0.920 (0.898 to 0.942) comparedwith the PS09 score (AUROC of 0.921; 0.902 to 0.939) and TRISS (0.929; 0.912 to0.947).

Conclusions

The BIG score is a good predictor of mortality in the adult trauma population. Itperformed well compared with TRISS and the PS09 score, although it hassignificantly less discriminative ability. In a penetrating-trauma population, theBIG score performed better than in a population with blunt trauma. The BIG scorehas the advantage of being available shortly after admission and may be used topredict clinical prognosis or as a research tool to risk stratify trauma patientsinto clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The early prediction of mortality in trauma patients is challenging but has importantpotential benefits. The utility of existing mortality-prediction tools is confined toretrospective applications such as quality assessment, as they rely on variables notavailable in the early phases of care (such as the injury severity score). Accurateearly prediction of the risk of death might have the potential to inform triagedecisions, inform treatment, or stratify patients for further care. In particular, itwould be attractive as an entry criterion for clinical trials to match an interventionto an appropriate at-risk population.

The BIG score (Admission base deficit (B), International normalized ratio (I), andGlasgow Coma Scale (G)) is a mortality-predicting score that has been shown to predictmortality accurately on admission in a cohort of pediatric trauma patients from amilitary trauma system. The BIG score performed better than other pediatric traumascoring systems and was validated in a separate pediatric population with similaraccuracy [1]. The BIG score has not been appliedto adults, and its accuracy has not been compared with that of existing traumamortality-prediction tools.

The first aim of this study was to assess whether the BIG score can predict mortality inan adult trauma population and to compare the predictive ability of the BIG score withthe commonly used mortality-predicting Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS; TraumaScore and Injury Severity Score (ISS) based on the ISS and the Revised Trauma Score(RTS), age and injury mechanism) and PS09 (Probability of Survival; model 09 based onISS, GCS, age, gender and intubation) score [1–5].

A second aim was to evaluate and compare the ability to predict mortality of all scoreson different subgroups.

Materials and methods

Data collection

A data-collection template was developed to collect all needed parameters from theparticipating sites. All primary admitted trauma-team activation patients aged 18years or older during the period 2005 to 2010, inclusive, were eligible. Onlypatients with available and complete datasets for the calculation of the analyzedscoring systems (BIG, TRISS, and PS09) were included in the study (n =15,730). In a second step, only patients with an ISS ≥4 were considered. Thisrequires at least an AIS 2 type of injury and excludes all minor injuries. Finally,data from 12,206 patients from one military and six civilian trauma centers andregistries in Europe and the United States were collected and retrospectivelyanalyzed. We used 30-day mortality as the primary outcome parameter of our analysis.We then compared the BIG score against the TRISS and PS09 score on a representativepopulation of trauma patients. Subgroup analysis only on patients with blunt orpenetrating trauma was additionally done.

Trauma centers and registries

Data were collected from four trauma centers participating in the InternationalTrauma Research Network (INTRN; Amsterdam, Oslo, London, San Francisco), from theGerman TraumaRegister DGU (TR-DGU) and also from two participating registries in theUnited States (Joint Theater Trauma Registry (JTTR) and the Trauma Registry of theOregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR). All participating sites arelevel-1 trauma centers.

INTRN

The International Trauma Research Network (INTRN) is a formal academic network ofhigh-volume trauma centers across Europe and the United States. The group was formedin 2009 and has grown strategically, developing fundamental, translational, andclinical research programs that span the complete breadth of trauma disciplines[6, 7].

TraumaRegister DGU

The TraumaRegister DGU (TR-DGU) is a prospective multicenter database withstandardized documentation of patients with severe trauma and thus requiringintensive care. This registry comprises detailed information on demographics andclinical and laboratory data. Data from the TraumaRegister DGU include patients fromabout 108 trauma units around Germany [8].

OHSU Trauma Registry

The Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Trauma Registry contains informationfrom more than 45,000 patients treated since 1985. The registry contains detailedinformation for each patient concerning prehospital, ED, and in-hospital care. Allresearch projects are approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB).

JTTR

The Joint Theatre Trauma Registry (JTTR) was established by the Department of Defenseto collect comprehensive data on all personnel, military and civilian, admitted tomilitary treatment facilities within Iraq and Afghanistan. It is maintained at the USArmy Institute of Surgical Research in San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Data are handled anonymously, and case identification is possible only through theparticipating hospital.

Trauma scores

For our analysis, we compared the original pediatric BIG score with the commonly usedTRISS and PS09 scores [1, 2, 9]. In a second approach, we tested the mortalityprediction of the BIG score on our blunt-trauma and separately on ourpenetrating-trauma patients and compared the score again with the TRISS and the PS09scores (Table 6).

The BIG score

The pediatric BIG score is a mortality-predicting score for children with traumaticinjuries. It was developed by Borgman and colleagues in 2011. They retrospectivelyanalyzed data from 2002 to 2009 and found that admission base deficit (B),international normalized ratio (I), and Glasgow Coma Scale (G) were independentlyassociated with mortality. The variables were combined into the pediatric BIG score(base deficit + (2.5 × international normalized ratio) + (15 Glasgow ComaScale)). This equation can then be implemented into a mortality-predicting formula:predicted mortality = 1/(1 + e-x), where x = 0.2 × (BIGscore) - 5.208. A BIG score of <12 points suggests a mortality of <5%, whereasa cut-off of >26 points corresponds to a mortality of >50%. The BIG score can beperformed rapidly on admission to evaluate severity of illness and to predictmortality in children [1].

The TRISS method

Physiological and anatomic data are included in the Trauma Injury Severity Score(TRISS) that was published in 1987 by Boyd and colleagues [2] based on a North American population. Since then, theestimation of prognosis is also discussed critically, which led to severalreevaluations of the score [10, 11]. TRISS combines the variables anatomic injury (ISS),physiological derangement (RTS), patient age, and injury mechanism to predictsurvival from trauma [2, 12]. TRISS quickly became the standard method for outcomeassessment [12, 13]. Forour analysis, we used the TRISS method with its coefficients published by Championand colleagues in 1990 (MTOS 1990) [14].

The PS09 Score (Probability of Survival, Model: 09)

In 2006, Bouamra and colleagues [19]published a new survival prediction model based on data from the UK Trauma Audit andResearch Network (TARN). Since 1989, TARN used TRISS as a score to predict outcome,initially with the MTOS 1990 coefficients, and later with UK TARN-derived TRISScoefficients. However, with the TRISS method, a large amount of data was lost. In thePS09 model, the prediction-model coefficients have been revised on recent data; themodel still includes all those subsets by using age, a transformation of ISS, GCS,gender, and Gender × Age interaction as predictors [9].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of this study is based on the data from six civilian and onemilitary database, extracting data from specified periods between 2005 and 2010.Demographic data are presented as means with standard deviation (SD) for continuousvariables and as percentages for incidence rates. The U test was used forcontinuous variables, and the test for categoric variables. Statistical significance was set at P valuesless than 0.05. The quality of all scoring systems in predicting mortality wasanalyzed and presented in terms of discrimination and precision. Discriminationmeasures the ability of a scoring system to separate survivors from nonsurvivors.This was measured with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves(AUROCs). The ROC curve summarizes the trade-off between sensitivity and specificityof a predictive score by using all score values as potential cut-off values. Itsvalue varies between 0.5 (no discrimination) and 1.0 (perfect discrimination). AUROCsare presented with 95% CI, and differences between AUROC curves were evaluated byusing a method derived by Hanley and colleagues [15]. In addition, the precision describes how well a score-basedprognosis is able to meet the observed mortality rate. All statistical analyses wereperformed by using IBM SPSS 20 (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In total, 12,206 patients were included in the study. Of those, 4,949 patients wereincluded by civilian trauma centers, and 7,257 (59%) patients were included by militarytrauma centers (Table 1).

Demographic data

Table 2 provides an overview of demographic and baselinephysiological data of each database. Data are presented as means or as percentages.The mean ISS was 15 ± 11 with a 30-day mortality rate of 4.8%. Table 4 presents all variables associated with mortality. In total, 588(4.8%) patients died. Survivors were younger (33.2 versus 50.4 years) and were morelikely to sustain penetrating trauma (47.5% versus 26.0%). Nonsurvivors had asignificantly higher ISS (33 versus 14; P < 0.001), a worse mean baseexcess (-6.9 versus -1.9; P < 0.001), and a lower GCS (7 versus 14; P < 0.001).

Quality criteria

Table 4 characterizes quality criteria for all scores compared.The table presents the discrimination and precision ability of the BIG, TRISS, andPS09 scores for all patients as well as for a blunt- and penetrating-traumapopulation. The AUROCof the BIG score and the TRISS score are significantly different(P < 0.001). The difference between the TRISS and PS09 scores is notstatistically significant (P = 0.32) in the combined dataset.

The expected mortality rate (precision) of the BIG score, PS09 score, and TRISS wascompared with the observed mortality rate. In Table 4, theobserved mortality of all patients is set by 4.8%. The expected mortality calculatedfor the BIG score is 4.8%, whereas the expected mortality of the TRISS and PS09scores are 6.6% and 7.9%, respectively.

Blunt trauma

Comparing only patients who sustained blunt trauma (n = 6,540), our analysisshows that the overall accuracy of the PS09 score had an AUROC of 0.921 (95% CI,0.911 to 0.932), the TRISS score of 0.917 (95% CI, 0.906 to 0.928), and the BIG scorehad an AUROC of 0.876 (95% CI, 0.859 to 0.892). The difference between AUROC of theBIG score and the TRISS score is significant (P < 0.001). The differencebetween the TRISS and PS09 score is not statistically significant (P = 0.24)in the blunt dataset.

Penetrating trauma

In patients with penetrating trauma (n = 5,666), the BIG score (0.920; 95%CI, 0.898 to 0.942) performed comparably to the PS09 score (0.921; 95% CI, 0.902 to0.939). The TRISS score had an AUROC of 0.929 (95% CI, 0.912 to 0.947). Thedifference between AUROC results in the penetrating group was not significant (allP > 0.16).

Military and civilian data

On a military dataset (n = 7,257), the BIG score had an AUROC of 0.929 (95%CI, 0.909 to 0.949), and the PS09 score had an AUROC of 0.922 (95% CI, 0.904 to0.940) and TRISS of 0.915 (95% CI, 0.891 to 0.939) (all P > 0.31). On acivilian dataset (n = 4949), the PS09 score had a similar AUROC (0.901; 95%CI, 0.887 to 0.914) to the TRISS (0.896; 95% CI, 0.882 to 0.909; P = 0.24).The AUROC of the BIG score (0.849; 95% CI, 0.830 to 0.868) was significantly lower(P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Figure 1 depicts the AUROCs for the BIG, TRISS, and PS09 scoreson all blunt and penetrating trauma patients combined.

Discussion

For the first time, the performance of the BIG score was analyzed on an adult traumapopulation. Data from civilian and military trauma centers and registries with arepresentative trauma population of blunt and penetrating trauma were used for thecurrent analysis. When all scores were tested on the whole dataset, the BIG scoreperformed well in predicting mortality in the adult trauma population. Unlike complexscoring systems, the BIG score can be used directly on admission of a trauma patient,because it uses variables that are rapidly available for assessing severity of illnessand predicting mortality. Time-consuming parameters like the ISS are not included withinthe BIG score. Hence, the BIG score might be used for trauma trials in which mortalityis the intended primary outcome parameter.

In the present analysis, the BIG score was shown to perform well in predicting mortalityin the penetrating-trauma population versus the blunt-trauma population. The TRISS andthe PS09 scores slightly overpredicted mortality in all subgroups. The BIG scoreoverpredicted mortality only in the penetrating-trauma group. In addition, the mortalityprediction of the BIG score was more accurate on military trauma data than on civiliandata. This might be due to its composition, as the BIG score includes parameters highlyreflecting the two major causes of acute death from trauma (for example, brain injuryand uncontrolled hemorrhage [1, 16–18]). Inassessing the epidemiology of trauma death, Sauaia and co-workers [19] identified central nervous system (CNS) injuries torepresent the most frequent cause of death (42%), followed by exsanguination (39%). TheBIG score reflects these observations by including INR and GCS in the calculation. TheINR provides information about the hemocoagulative status of the patient [17, 20, 21],whereas the GCS is used as a surrogate marker for the level of consciousness and toestimate its severity, due to either traumatic brain injury (TBI) or severehypoperfusion [22–24]. However, the GCS was recently challenged, and the role as atool to reflect the mental status of a trauma patient is widely discussed [25].

The third parameter of the BIG score, base deficit (BD), was shown to be a valuableindicator of shock, abdominal injury, fluid requirements, efficacy of resuscitation, anda predictor of mortality after trauma [26–31].

In the past, several scoring systems and algorithms have been developed to predictmortality in the trauma population. The one most closely related to the BIG score is theEmergency Trauma Score (EMTRAS), developed by Raum and colleagues [32] from data derived from the TraumaRegister DGU. Thisscore includes similar components to the BIG score, including GCS, base excess (BE), andprothrombin time (PT), as well as age. When this score was compared with the RevisedTrauma Score (RTS), ISS, NISS, and TRISS scores with regard to mortality after trauma,the EMTRAS was superior. However, the EMTRAS was developed and validated on one singleand retrospective database and therefore has not been validated externally orprospectively [32]. Perel and co-workers[33] recently developed a prognostic modelfor early death in patients with traumatic bleeding on a dataset from the ClinicalRandomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage (CRASH-2) trial andvalidated the score on 14,220 selected trauma patients from the Trauma Audit andResearch Network (TARN). Glasgow coma scale score, age, and systolic blood pressure werethe strongest predictors of mortality. A chart was constructed to provide theprobability of death at the point-of-care. Future research must evaluate whether the useof this prognostic model in clinical practice has an effect on the management andoutcomes of trauma patients [33].

Most other scoring systems and algorithms to predict mortality in the trauma populationon admission are limited because of their complexity and the high number of variablesincluded for calculation. With this, the Trauma Injury Severity Score (TRISS), forexample, offers a standard approach for evaluating outcome of trauma care [2]. Similar to the TRISS, the PS09 score uses acombination of anatomic and physiological parameters. However, information on the entireand complete injury pattern is usually difficult to obtain in the acute phase ofEmergency Department (ED) care and requires potentially time-consuming imagingtechnology. Limitations of both scores are multiple and widely discussed in theliterature [2, 9, 10]. Of note, it also takes trained personnel significant time toreview charts and calculate complex scores, so that the clinical use of these approacheshas to be questioned.

Limitations of the present study are the same that are inherent in retrospective reviewsusing registry data. To generate the dataset for the present analysis, a number ofpatients had to be excluded as a result of missing data in the contributing registries,resulting in a selection bias of patients. Only patients with complete datasets wereincluded in the study. In a subgroup analysis, we excluded patients with minor injuries(ISS < 4), which reduced the dataset by about 20%. These excluded patients are mostlikely survivors. Trauma mortality scores must be evaluated on a trauma population witha certain amount of injury severity to predict mortality accurately. On a traumapopulation without an ISS limitation, we proved that all three scores had slightlybetter AUROC results, because outcome prediction is easy in the group of patients withminor injuries.

The fact that one registry (San Francisco) obviously contributed more severely injuredpatients with impaired outcome into the joint dataset might also have biased theresults. A similar effect may have been related to the contribution of morepenetrating-trauma patients derived from the military database.

The BIG score waives the need for anatomic classifications and physiologic parameters,like systolic blood pressure, heart rate, or respiratory rate. The GCS is a simpleclinical assessment, whereas BE and INR can easily and quickly be obtained frompoint-of-care devices in the ED setting. These results are usually known within minutesof ED arrival. The BIG score does not require any variables that are not readilyavailable in the acute phase of injury care (for example, ISS, NISS). Therefore, wethink that the BIG score can be used to identify trauma patients at risk. However, theBIG score was shown to predict mortality accurately in an adult trauma population, andit may be used to determine inclusion criteria for prospective acute care researchstudies.

Conclusions

Our results show that the BIG score, initially developed and validated in the pediatrictrauma population, can also predict mortality in the adult trauma population. The BIGscore performs well compared with complex scoring systems like the TRISS and PS09scores, although it has significantly less discriminative ability. The score was shownto perform superiorly in the penetrating trauma-population and on a military dataset,which could make it a useful system in combat casualties, for whom time and resourcesare limited. In addition, the BIG score can be used independent of injury severity, andit can be used to determine inclusion criteria for prospective acute care researchstudies.

Key messages

-

This study validated three mortality-predicting scores on amulticenter database with military and civilian data.

-

The BIG score has been shown to predict mortality in pediatric traumapatients. Our analysis show that this score can also be used on a representative adulttrauma population.

-

In the present analysis, the BIG score was shown to perform well inpredicting mortality in the penetrating trauma population versus the blunt traumapopulation.

-

The BIG score is based on information available shortly afteradmission.

-

Mortality predicting scores that are quickly available in theEmergency Department can be a useful tool to include patients in acute care researchstudies.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated Injury Scale

- AUROC:

-

area under the receiver operating characteristic

- BD:

-

base deficit

- BE:

-

base excess

- BIG:

-

base excess: International normalized ratio:Glasgow coma scale

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- ED:

-

emergencydepartment

- EMTRAS:

-

Emergency Trauma Score

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- ICU:

-

intensive careunit

- INR:

-

International Normalized Ratio

- INTRN:

-

International Trauma Research Network

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- JTTR:

-

Joint Theatre Trauma Registry

- NISS:

-

New InjurySeverity Score

- OHSU:

-

Oregon Health & Science University

- PS:

-

probability ofsurvival

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- RTS:

-

RevisedTrauma Score

- TARN:

-

Trauma Audit and Research Network

- tbi:

-

traumatic brain injury

- TR-DGU:

-

TraumaRegister DGU of the German Trauma Society (DGU).

References

Borgman M, Maegele M, Wade CE, Blackbourne LH, Spinella PC: Pediatric trauma BIG score: predicting mortality in children after military andcivilian trauma. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: e892-e897. 10.1542/peds.2010-2439.

Boyd CR: Evaluating trauma care: the TRISS method: Trauma Score and the Injury SeverityScore. J Trauma. 1987, 27: 370-378. 10.1097/00005373-198704000-00005.

Bouamra O, Wrotchford A, Hollis S, Vail A, Woodford M, Lecky F: A new approach to outcome prediction in trauma: a comparison with the TRISSmodel. J Trauma. 2006, 61: 701-710. 10.1097/01.ta.0000197175.91116.10.

Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA: A revision of the Trauma Score. J Trauma. 1989, 29: 623-629. 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00017.

TARN: PS12 Calculations. [http://www.tarn.ac.uk/Content.aspx?c=1895]

Frith D, Goslings JC, Gaarder C, Maegele M, Cohen MJ, Allard S, Johansson PI, Stanworth S, Thiemermann C, Brohi K: Definition and drivers of acute traumatic coagulopathy: clinical and experimentalinvestigations. J Thrombosis Haemost. 2010, 8: 1919-1925. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03945.x.

Stanworth SJ, Morris TP, Gaarder C, Goslings JC, Maegele M, Cohen MJ, König TC, Davenport R, Pittet J-F, Johansson PI, Allard S, Johnson T, Brohi K: Reappraising the concept of massive transfusion in trauma. Crit Care. 2010, 14: R239-10.1186/cc9394.

Arbeitsgemeinschaft "Scoring" der Deutschen Gesellschaft fuer Unfallchirurgie(DGU). Das Traumaregister der Deutschen Gesellschaft fuer Unfallchirurgie. Unfallchirurg. 1994, 97: 230-237.

Bouamra O, Wrotchford A, Hollis S, Vail A, Woodford M, Lecky F: Outcome prediction in trauma. Injury. 2006, 37: 1092-1097. 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.029.

Millham FH, LaMorte WW: Factors associated with mortality in trauma: re-evaluation of the TRISS methodusing the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma. 2004, 56: 1090-1096. 10.1097/01.TA.0000119689.81910.06.

Gabbe BJ: TRISS: does it get better than this?. Acad Emerg Med. 2004, 11: 181-186.

Chawda MN, Hildebrand F, Pape HC, Giannoudis PV: Predicting outcome after multiple trauma: which scoring system?. Injury. 2004, 35: 347-358. 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00140-2.

Senkowski CK, McKenney MG: Trauma scoring systems: a review. JACS. 1999, 189: 491-503.

Champion HR: The Major Trauma Outcome Study. JTrauma. 1990, 30: 1356-1365.

Hanley J, McNeil B: A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curvesderived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983, 148: 839-843.

Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, Coats T: Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma. 2003, 54: 1127-1130. 10.1097/01.TA.0000069184.82147.06.

Hess JR, Brohi K, Dutton RP, Hauser CJ, Holcomb JB, Kluger Y, Mackway-Jones K, Parr MJ, Rizoli SB, Yukioka T, Hoyt DB, Bouillon B: The coagulopathy of trauma: a review of mechanisms. J Trauma. 2008, 65: 748-754. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181877a9c.

Maegele M, Lefering R, Yucel N, Tjardes T, Rixen D, Paffrath T, Simanski C, Neugebauer E, Bouillon B: Early coagulopathy in multiple injury: an analysis from the German Trauma Registryon 8724 patients. Injury. 2007, 38: 298-304. 10.1016/j.injury.2006.10.003.

Sauaia A: Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma. 1995, 38: 185-193. 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00006.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA: Acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanism, identification and effect. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007, 680-685.

Mitra B, Cameron P, Mori A, Maini A, Fitzgerald M, Paul E, Street A: Early prediction of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Resuscitation. 2011, 82: 1208-1213. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.04.007.

Hoffmann M, Lefering R, Rueger JM, Kolb JP, Izbicki JR, Ruecker H, Rupprecht M, Lehmann W: Pupil evaluation in addition to Glasgow Coma Scale components in prediction oftraumatic brain injury and mortality. Br J Surg. 2012, 99 (Suppl 1): 122-130.

Teasdale G: Adding up the Glasgow Coma Score. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1979, 28: 13-16.

Duncan R, Thakore S: Decreased Glasgow Coma Scale score does not mandate endotracheal intubation in theemergency department. JEmerg Med. 2009, 37: 451-455. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.11.026.

Green SM: Cheerio, laddie! Bidding farewell to the Glasgow Coma Scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2011, 58: 427-430. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.009.

Davis JW, Parks SN, Kaups KL, Gladen HEO´d-NS: Admission base deficit predicts transfusion requirements and risk ofcomplications. J Trauma. 1996, 41: 769-774. 10.1097/00005373-199611000-00001.

Mizushima Y, Ueno M, Watanabe H, Ishikawa K, Matsuoka T: Discrepancy between heart rate and makers of hypoperfusion is. 2011, 71: 789-792.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay M, Mackersie RC, Pittet J-F: Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through theprotein C pathway?. Ann Surg. 2007, 245: 812-818. 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31.

Tremblay LN, Feliciano DVRG: Assessment of initial base deficit as a predictor of outcome: mechanism of injurydoes make a difference. Am Surgeon. 2002, 68: 689-693.

Hodgman EI, Morse BC, Dente CJ, Mina MJ, Shaz BH, Nicholas JM, Wyrzykowski AD, Salomone JP, Rozycki GS, Feliciano DV: Base deficit as a marker of survival after traumatic injury: consistent acrosschanging patient populations and resuscitation paradigms. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72: 844-851.

Rixen D, Raum M, Bouillon B, Lefering R, Neugebauer E, Arbeitsgemeinschaft "Polytrauma" of the Deutsche Gesellschaft furUnfallchirurgie": Base deficit development and its prognostic significance in posttrauma criticalillness: an analysis by the trauma registry of the Deutsche Gesellschaft fürUnfallchirurige. Shock. 2001, 15: 83-89.

Raum MR, Nijsten MWN, Vogelzang M, Schuring F, Lefering R, Bouillon B, Rixen D, Neugebauer E, Ten Duis HJ: Emergency trauma score: an instrument for early estimation of trauma severity. Crit Care Med. 2009, 37: 1972-1977. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fe96a.

Perel P, Prieto-Merino D, Shakur H, Clayton T, Lecky F, Bouamra O, Russell R, Faulkner M, Steyerberg EW, Roberts I: Predicting early death in patients with traumatic bleeding: development andvalidation of prognostic model. BMJ. 2012, 345: e5166-e5166. 10.1136/bmj.e5166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TB contributed to study design, acquisition and interpretation of data, recording ofpaper and analyzing data. PS, KB, MM, MS, and MB conceived of the study, providedstatistical advice on study design, and analyzed data. RL, KB, and MM contributed toanalysis and interpretation of data and revision of the article. All other authorscontributed to data collection and to manuscript revision. All authors read and approvedthe final manuscript for publication.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Brockamp, T., Maegele, M., Gaarder, C. et al. Comparison of the predictive performance of the BIG, TRISS, and PS09 score in anadult trauma population derived from multiple international trauma registries. Crit Care 17, R134 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12813

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12813