Abstract

NSAIDs are among the most commonly used drugs worldwide and their beneficial therapeutic properties are thoroughly accepted. However, they are also associated with gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events. NSAIDs can damage the whole GI tract including a wide spectrum of lesions. About 1 to 2% of NSAID users experienced a serious GI complication during treatment. The relative risk of upper GI complications among NSAID users depends on the presence of different risk factors, including older age (>65 years), history of complicated peptic ulcer, and concomitant aspirin or anticoagulant use, in addition to the type and dose of NSAID. Some authors recently reported a decreasing trend in hospitalizations due to upper GI complications and a significant increase in those from the lower GI tract, causing the rates of these two types of GI complications to converge. NSAID-induced enteropathy has gained much attention in the last few years and an increasing number of reports have been published on this issue. Current evidence suggests that NSAIDs increase the risk of lower GI bleeding and perforation to a similar extent as that seen in the upper GI tract. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors have the same beneficial effects as nonselective NSAIDs but with less GI toxicity in the upper GI tract and probably in the lower GI tract. Overall, mortality due to these complications has also decreased, but the in-hospital case fatality for upper and lower GI complication events has remained constant despite the new therapeutic and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 5,000 years have passed since a Greek physician prescribed extracts of willow bark for musculoskeletal pain. But it was not until 1897 that Felix Hoffman synthesized acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), the first NSAID [1]. Nowadays, NSAIDs are among the most commonly used drugs worldwide and their analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic therapeutic properties are thoroughly accepted. More than 30 million people use NSAIDs every day, and they account for 60% of the US over-the-counter analgesic market [2]. Like many other drugs, however, NSAIDs are associated with a broad spectrum of side effects, including gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular (CV) events, renal toxicity, increased blood pressure, and deterioration of congestive heart failure among others. In this review, we will focus on upper and lower GI tract injury.

Several classes of NSAIDs with different GI toxicity can be distinguished: traditional or nonselective NSAIDs (ns-NSAIDs), including high-dose ASA, which inhibit both isoforms of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme and are the most toxic NSAID compounds; COX-2 selective inhibitors that produce less GI damage; and new classes of NSAID, including nitric oxide NSAIDs and hydrogen sulfide-releasing NSAIDs that still are being tested in different conditions and apparently have less upper GI and CV toxicity.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated upper gastrointestinal damage

The damage of gastric and duodenal mucosa caused by NSAIDs has been widely studied. These upper GI side effects include troublesome symptoms with or without mucosal injury, asymptomatic mucosal lesions, and serious complications, even death.

About 30 to 50% of NSAID users have endoscopic lesions (such as subepithelial hemorrhages, erosions, and ulcerations), mainly located in gastric antrum, and often without clinical manifestations. Generally, these lesions have no clinical significance and tend to reduce or even disappear with chronic use, probably because the mucosa is adapted to aggression [3, 4]. On the contrary, up 40% of NSAIDs users have upper GI symptoms, the most frequent being gastroesophageal reflux (regurgitation and/or heartburn) and dyspeptic symptoms (including belching, epigastric discomfort, bloating, early satiety and postprandial nausea) [3]. The onset of these symptoms seems to vary depending on the type of NSAID. A meta-analysis of the available trials from the Cochrane collaboration concluded that COX-2 selective inhibitor (celecoxib) was associated with less symptomatic ulcers, endoscopically detected ulcers and discontinuations for GI adverse events compared with ns-NSAIDs (naproxen, diclofenac, ibuprofen and loxoprofen) [5]. Unfortunately, these symptoms are not predictive of the presence of mucosal injury. Approximately 50% of patients with symptoms have no mucosal lesions; however, >50% of users with serious peptic ulcer complications had no previous warning symptoms [3, 6].

The most important upper GI side effects are the occurrence of symptomatic and/or complicated peptic ulcer. NSAID-related upper GI complications include bleeding, perforation and obstruction. About 1 to 2% of NSAID users experienced a serious complication during treatment. Case-control studies and a meta-analysis have shown that the average relative risk (RR) of developing uncomplicated or complicated peptic ulcer is fourfold and fivefold in NSAIDs users compared with nonusers [7–9]. The risk is suggested to be higher during the first month of treatment (RR, 5.7; 95% confidence interval CI, 4.9 to 6.6), but remains elevated during the intake and 2 months after stopping therapy [8].

As we mentioned previously, in many cases the first evidence of NSAID toxicity is a GI complication. That is the main reason to say that prevention therapies should be implemented based on the presence of risk factors and not after the occurrence of dyspeptic symptoms.

Risk factors for gastrointestinal complications

The main risk factors for NSAID-related GI complications (Table 1) are: older age (age ≥65 years, especially ≥70 years); prior uncomplicated or complicated ulcer; concomitant use of other drugs, including aspirin, other nonaspirin antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, cortico-steroids or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; severe illness; alcohol and tobacco use; and Heliobacter pylori infection [10]. H. pylori infection and NSAID use have synergistic effects on risk. A meta-analysis of 16 studies showed that the odds ratio for peptic ulcer in patients with both risk factors (H. pylori-positive NSAID use) was 61.1 (95% CI, 9.98 to 373)), compared with H. pylori- negative nonusers [11]. Some of these risk factors can be modified. For example, two studies have showed that H. pylori eradication before starting NSAID therapy reduces the rate of peptic ulcer, but eradication in long-term NSAID users seems to be not effective in preventing peptic ulcer disease [12, 13].

Are NSAIDs equally harmful to the upper gastrointestinal tract?

Based on current evidence, the RR of GI bleeding is not the same with the different types of NSAIDs.

Traditional or nonselective NSAIDs

Traditional or ns-NSAIDs, including high dose of ASA, are considered the most GI harmful kind of NSAID. GI damage is dose dependent, and slow-release formulations and drugs with longer half-life also have greater toxicity. A recent Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies (the SOS Project) confirms variability in the risk of GI complications among individual NSAIDs as used in clinical practice. The RR ranged from <2 for aceclofenac, ibuprofen and celecoxib, between 2-4 for rofecoxib, meloxicam, nimesulide, sulindac, diclofenac and ketoprofen, and between 4 to 5 for tenoxicam, naproxen, diflunisal and indomethacin, and more than 5 for piroxicam, azapropazone and ketorolac [14]. These differences may be attributed in part to the dose and formulations. For individual NSAIDs, data on the effect of dose and duration of use are still scant.

Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors

The identification of the gene for the COX-2 isoenzyme in 1991 opened the door to development of NSAIDs that selectively inhibit COX-2. This isoenzyme expression can be induced by inflammatory mediators in multiples tissues and can have an important role in the mediation of pain, inflammation and fever. Selective COX-2 inhibitors inhibit this enzyme, but keep prostaglandin production via COX-1, which is involved in the maintenance of GI mucosal integrity. As a result, these drugs should in theory be safer than ns-NSAIDs for the development of upper GI complications, although COX-1 inhibition is not the only mechanism involved in GI toxicity.

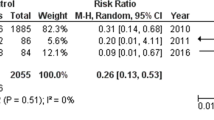

A 2007 systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that selective COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) produced significantly fewer ulcers (RR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.30) and ulcer complications (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.50) as well as better GI tolerability compared with ns-NSAIDs [15]. One should keep in mind that concomitant use of low-dose ASA for CV prophylaxis is frequent among NSAID users (approximately 20 to 25% in clinical trials), mainly in older people. Evidence from subgroup analyses of the systematic review above mentioned [15] and several RCTs (the CLASS [16], TARGET [17] and SUCCES-1 [18] studies) suggests that this benefit might be reduced with the co-administration of low dose ASA. In spite of this, a meta-analysis of all available trials that include users of low-dose ASA combined with NSAIDs (traditional or selective) showed a lower GI complication risk in the group of selective COX-2 NSAID plus low-dose ASA users compared with ns-NSAID plus low-dose ASA users (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.95) [19]. One should point out that these studies were nonrandomized trials and the data result from indirect comparisons.

Also of interest is a recent systematic review of RCTs that compare COX-2 inhibitors versus ns-NSAIDs plus proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with regard to GI safety. The review involved 7,616 patients and concluded that COX-2 inhibitors reduce significantly the risk of perforation, obstruction, and bleeding (RR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.56; P <0.001) compared with ns-NSAIDs plus PPIs, but this benefit was significant only for high-risk and long-term users [20]. Selective COX-2 inhibitors are therefore as effective as ns-NSAIDs to relieve inflammation but they can reduce NSAID-associated GI toxicity. These GI benefits of selective NSAIDs have to be balanced against the known CV risk, although CV toxicity is not exclusive of selective COX-2 NSAIDs. Rofecoxib (no longer in the market), etoricoxib and diclofenac (among ns-NSAIDs) seem to have the worst CV profiles [21].

New NSAIDs compounds

Nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide are potent vasodilator molecules and increase mucosal protection, keeping its wholeness. This has led to the concept that coupling a NSAID and nitric oxide or hydrogen sulfide molecules could overcome the negative effects produced by prosta-glandin inhibition.

The nitric oxide-releasing NSAIDs, or COX-inhibiting nitric oxide donator, have been investigated as a potentially safer alternative to selective and ns-NSAIDs. Naproxcinod was the first and only COX-inhibiting nitric oxide donator investigated in clinical trials, showing a slight improvement in GI tolerability compared with naproxen. Owing to the lack of outcome studies and potential side effects not yet fully evaluated, this compound has not obtained the green light to be commercialized by official drug agencies in Europe and the USA [22].

NSAIDs that release hydrogen sulfide are being investigated in preclinical models.

Time trends of gastrointestinal complications and hospitalization due to them

Over the past decades, there have been significant changes in the rate of hospitalizations due to GI complications. A 2004 multicenter study reported that rates of hospitalization for NSAID gastropathy first increased from 0.6% per year in 1981 to a peak of 1.5% in 1992, and then decreased to 0.5% in 2000 [23]. The last change could be attributed to several factors: use of lower doses of NSAIDs, an increase in less toxic NSAID and PPI use, and decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection.

Looking at reported time trends for hospitalizations due to GI events (overall and not only NSAID-associated GI complications), we could say that hospitalizations owing to uncomplicated peptic ulcer are decreasing over time [24, 25]. However, there were discrepancies concerning hospitalizations owing to complicated ulcers. Generally, studies that reported decreasing peptic ulcer bleeding rates were more recent and were population based. In this regard, it is interesting to highlight a Spanish study by Lanas and colleagues published in 2011 [26]. The authors showed that the incidence per 100,000 person-years of hospitalizations due to upper GI ulcer bleeding and perforations decreased over time (from 54.6 and 3.9 in 1996 (R2 = 0.944) to 25.8 and 2.9 in 2005 (R2 = 0.410), respectively). Of patients with upper GI events, 21% and 15% of patients with upper GI events were NSAID or antiplatelet users, respectively [27]. This tendency contrasted with a progressive and significant increase in the incidence of hospitalizations due to lower GI complications (colonic diverticular and angiodysplasia bleeding, and a small increasing trend of intestinal perforations).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated lower gastrointestinal damage

As we have pointed out above, the association of NSAID use with upper GI damage is well documented; however, the association with damage to the lower GI tract has not been widely studied and remains poorly characterized. NSAID-induced enteropathy has gained much attention due to the introduction of new diagnostic modalities such as capsule endoscopy (CE) and device-assisted enteroscopy, as well as the increased use of low-dose aspirin (ASA) and NSAIDs. A number of reports have suggested that NSAIDs also cause lower GI tract injury and complications. The clinical significance and frequency of adverse events with ns-NSAIDs in the lower GI tract have been increasingly reported (Table 2).

Epidemiology

Recent publications have shown that the incidence of lower GI complications (including ulceration, bleeding, obstruction or perforation), many of them related to NSAID and ASA use, is increasing whereas the incidence of upper GI complications is decreasing [28] (Figure 1). The ratio of upper/lower complications was 4.1 in 1996 but decreased to only 1.4 in 2005 [27, 28]. Current evidence suggests that NSAIDs increase the risk of lower GI bleeding and perforation to a similar extent as that seen in the upper GI tract [29].

Time trends of gastrointestinal events. Estimated number of events per 100,000 person-years on the basis of the adjudication of events in the validation process. Figure constructed using data from [27]. GI, gastrointestinal.

Post-hoc analysis of the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) trial concluded that lower GI events accounted for 40% of all serious GI events in patients on NSAIDs [30]. CE studies in healthy subjects taking either short-term or long-term NSAIDs have presented evidence of mucosal damage in the small bowel. Graham and colleagues performed a CE study in arthritic patients who had been using NSAIDs for at least 3 months and showed an incidence of small intestinal mucosal injury as high as 71% [31]. In healthy volunteers, Maiden and colleagues reported that slow-release diclofenac use for 2 weeks resulted in macroscopic injury to the small intestine in 68 to 75% of subjects [32]. In addition, Goldstein and colleagues reported that 2 weeks of naproxen plus omeprazole ingestion induced small-bowel mucosal breaks in 55% of volunteers [33].

Growing evidence indicates that ASA can also damage the lower GI tract. A systematic review reported an increase of fecal blood loss (0.5 to 1.5 ml/day) in low-dose ASA users (<325 mg) [34]. A study in healthy volunteers has shown that even enteric-coated ASA was associated with development of erosions and ulcers in 50% of volunteers [35]. The clinical significance of these findings is not yet clear.

Evidence suggests that COX-2 selective inhibitors are associated with fewer mucosal lesions of the small bowel than are ns-NSAIDs plus a PPI in CE studies performed in healthy subjects [36, 37]. The Celecoxib versus Omeprazole and Diclofenac in Patients with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis (CONDOR) trial reported recently that the risk of clinically significant events from both the upper and lower GI tract were almost four times lower in at-risk osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with celecoxib 200 mg twice daily when compared with those receiving slow-release diclofenac 75 mg twice daily plus omepra-zole 20 mg/day [38].

Subclinical and clinical pictures

The prevalence of NSAID-related lower GI adverse effects, including both clinical and subclinical manifestations, may exceed those detected in the upper GI tract and include a wide spectrum of lesions.

Anemia and blood loss

In long-term NSAID users, continuous and mild blood loss produced by NSAID enteropathy may result in iron deficiency and anemia. No studies have been performed to determine the exact burden and clinical impact of this problem in patients taking NSAIDs or ASA. Furthermore, in many instances, there is no close relationship between demonstrable lesions on the upper GI tract and GI blood loss [39]. Morris and colleagues showed that 47% of NSAID users for rheumatoid arthritis with chronic iron deficiency anemia who had negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy findings had small-bowel ulcerations, and they concluded that this could be the reason for the development of anemia [40]. Moore and colleagues performed a systematic review including 1,162 subjects and found that most NSAIDs and ASA (325 mg) resulted in a small average increase in fecal blood loss of 1 to 2 ml/ day from about 0.5 ml/day at baseline [34]. Some individuals lost much more blood than average, 5% of those taking NSAIDs had daily blood loss ≥5 ml and 1% had dialy blood loss higher than 10 ml. For ASA at daily doses ≥1,800 mg, the rates of daily blood loss of 5 ml/day or 10 ml/day were 31% and 10%, respectively.

Inflammation and increased permeability

The development of increased gut permeability and mucosal inflammation are the most frequent abnormalities in NSAID users [41]. Increased gut permeability can be seen as soon as 12 hours after the ingestion of single doses of most NSAIDs, but it is not observed in NSAIDs without enterohepatic recirculation (nabumetone, ASA) [41–44]. Short-term studies with COX-2 selective inhibitors have shown that these agents do not increase intestinal permeability [45, 46]. Some studies have found that NSAIDs increase fecal calprotectin in rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis patients taking NSAIDs [47].

These tests have shown that intestinal inflammation is present in 60 to 70% of patients taking NSAIDs and that, once established, it may be detected up to 1 to 3 years after the long-term NSAID use has been stopped. Small intestine permeability is necessary for the subsequent development of small intestine inflammation, which is associated with blood and protein loss, but it is often silent [48].

Mucosal ulceration

CE and enteroscopic studies have shown that NSAID use induces erythema, mucosal hemorrhage, erosions and intestinal ulceration in the small bowel, confirming previous autopsy data [49, 50]. Some reports suggest that this type of lesion can be seen in up to 40% of rheumatic NSAIDs users [31, 50]. Colonoscopy studies have also shown that NSAID intake is associated with isolated colonic ulcers, diffuse colonic ulceration that could be associated with occult bleeding, major GI bleeding and/ or perforation [51–53].

Major complications

Lanas and colleagues reported in the early 1990s that 86% of patients admitted to hospital with lower GI bleeding had evidence of recent (<7 days) NSAID or ASA use [52, 53], and a similar scenario was found later with intestinal perforation [53]. Recently, the presence of severe clinical side effects of the lower GI tract associated with NSAID use were confirmed by post-hoc analysis of different RCTs [54–56].

Current evidence shows contradictory results concerning the safety of COX-2 selective inhibitors because post-hoc analyses of the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) and MEDAL trials have reported different results. In the VIGOR trial, lower GI events were as frequent as upper GI events, and the benefits of rofecoxib 50 mg/day over naproxen (500 mg twice daily) were present in both the upper and the lower GI tract, with a similar risk reduction of 50% and 60%, respectively [54]. However, in the MEDAL trial, although the incidence of lower GI events exceeded that seen in the upper GI tract (patients were advised to take PPIs if they had risk factors), there were no benefits of etoricoxib over diclofenac when looking at the incidence of lower GI complications [30]. CONDOR trial recently found that the risk of clinically significant outcomes throughout the entire GI tract were lower in patients treated with celecoxib 200 mg twice daily compared with those patients taking slow-release diclofenac 75 mg twice daily plus omeprazole 20 mg/day [38]. The authors concluded the need to review the actual preventive strategies for chronic NSAID users.

Another clinical side effect associated with NSAID use in the lower GI tract is complicated diverticular disease. A systematic review found a positive association of complicated diverticular disease with ns-NSAID use [57]. Wilcox and colleagues reported that the risk for lower GI bleeding among patients taking NSAIDs was 2.6 times higher compared with nonuse (95% CI, 1.7 to 3.9) [58]. The specific risk for diverticular bleeding was increased 3.4-fold (95% CI, 1.9 to 6.2) in NSAID users.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-related mortality

Patients developing an upper and lower GI complication are at risk of dying [59]. This risk is probably higher in older people [60] and/or in people with co-morbidities and/or with large ulcers in the posterior duodenal bulb or on the lesser curvature. The reported peptic ulcer bleeding-related mortality rates range from 5 to 12%. Most studies from the United States, Europe, and Asia place that figure closer to 5% than to 12% [27, 29, 61].

A recent study published by Sonnenberg looking at the time trends of ulcer disease in a representative sample of six European countries concluded that the risk of death from gastric and duodenal ulcers increased among consecutive generations born during the second half of the nineteenth century until shortly before the turn of the century and then decreased in all subsequent generations [62]. The increase in NSAID consumption or introduction of potent anti-secretory medications has not affected the long-term downward trends of ulcer mortality.

A recent Spanish population-based study looking at patients hospitalized because of GI adverse events between 1998 and 2006 reported that, overall, there was a statistically significant decrease in the sex-standardized and age-standardized mortality rate owing to a decrease in the number of patients hospitalized because of GI events over time [27]. When stratified by source, the decrease was not present in patients with lower GI events. However, the case fatality rate did not change over the study period for all types of GI complication events. One should note that the mean age of fatal cases remained constant during the study period. The authors concluded that the reduction observed in mortality associated with hospitalizations because of GI events was due to the observed decreased rate of upper GI events, probably associated with our ability to prevent those complications [15, 63]. One should also highlight that recent publications note that most peptic ulcer bleeding-related deaths are not a direct consequence of the bleeding ulcer itself. Instead, mortality derives from cardio-pulmonary conditions, multiorgan failure or terminal malignancy, suggesting that improving treatments of the bleeding ulcer may affect mortality very little [64].

Recognition of these associations is essential for the improvement of therapeutic strategies that focus not only on the GI tract, but also on providing supportive care and preventing complications and key-organ failure. The identification of non-GI risk factors associated with poor outcomes in peptic ulcer bleeding patients and a multidisciplinary approach for high-risk patients should help to reduce this outcome.

Key messages

-

The presence of upper GI symptoms (dyspepsia and reflux) is not predictive of the occurrence of GI complications.

-

The RR of developing serious GI complications is threefold to fivefold greater among NSAIDs user than among nonusers. The presence of risk factors is important to determine the actual risk of patients using NSAIDs.

-

The most relevant upper GI risk factors are history of prior peptic ulcer, older age and concomitant use of low-dose aspirin.

-

Before prescribing NSAIDs, the evaluation of both the CV and GI risk factors are mandatory.

-

The risk of upper clinical significant GI events is lower for COX-2 selective inhibitor users than for those receiving ns-NSAIDs in the at-risk population.

-

Over the past decade, hospitalizations due to upper GI complications have decreased, whereas the number of lower GI complications has increased.

-

Current evidence suggests that NSAIDs increase the risk of lower GI bleeding and perforation to a similar extent as that seen in the upper GI tract.

-

Selective COX-2 inhibitors are as effective as traditional NSAIDs to relieve inflammation.

-

The COX-2 selective inhibitor celecoxib seems to be associated with lower GI mucosal damage and clinically significant events from the entire GI tract compared with ns-NSAIDs alone or those associated with omeprazole.

-

Reported peptic ulcer bleeding related mortality rates range from 5 to 12% in developed countries.

-

Most peptic ulcer bleeding-associated deaths are not direct sequelae of the bleeding ulcer itself. Instead, mortality derives from cardiopulmonary conditions, multiorgan failure and malignant condition.

Abbreviations

- ASA:

-

acetylsalicylic acid

- CE:

-

capsule endoscopy

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CONDOR:

-

Celecoxib versus Omeprazole and Diclofenac in Patients with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

- COX:

-

cyclooxygenase

- CV:

-

cardiovascular

- GI:

-

gastrointestinal

- MEDAL:

-

Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term

- NSAID:

-

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- ns-NSAID:

-

nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PPI:

-

proton pump inhibitor

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

relative risk

- VIGOR:

-

Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research.

References

Brune K, Hinz B: The discovery and development of antiinflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 2391-2399. 10.1002/art.20424.

Singh G: Gastrointestinal complications of prescription and over-thecounter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a view from the ARAMIS database. Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System. Am J Ther. 2000, 7: 115-121. 10.1097/00045391-200007020-00008.

Larkai EN, Smith JL, Lidsky MD, Graham DY: Gastroduodenal mucosaand dyspeptic symptoms in arthritic patients during chronic steroidal antiinflammatory drug use. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987, 82: 1153-1158.

Lanas A, Hunt R: Prevention of anti-inflammatory drug induced gastrointestinal damage: beneficts and risks of therapeutic strategies. Ann Med. 2006, 38: 415-428. 10.1080/07853890600925843.

Moore RA, Derry S, Makinson GT, McQuay HJ: Tolerability and adverse events in clinical trials of celecoxib in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of information from company clinical trial reports. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005, 7: R644-R665. 10.1186/ar1704.

Armstrong CP, Blower AL: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and life threatening complications of peptic ulceration. Gut. 1987, 28: 527-532. 10.1136/gut.28.5.527.

Perez Gutthann S, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Raiford DS: Individual nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and other risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Epidemiology. 1997, 8: 18-24. 10.1097/00001648-199701000-00003.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia-Rodríguez LA: Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/ perforation. An overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 2093-2099. 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2093.

Huang J-Q, Sridhar S, Hunt RH: Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002, 359: 14-22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07273-2.

Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A: Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010, 24: 121-132.

Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH: Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002, 359: 14-22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07273-2.

Chan FK, Sung JJ, Chung SC, To KF, Yung MY, Leung VK, Lee YT, Chan CS, Li EK, Woo J: Randomised trial of eradication of Helicobacter pylori before non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy to prevent peptic ulcers. Lancet. 1997, 350: 975-979. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04523-6.

Chan FK, To KF, Wu JC, Yung MY, Leung WK, Kwok T, Hui Y, Chan HL, Chan CS, Hui E, Woo J, Sung JJ: Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and risk of peptic ulcers in patients starting long-term treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002, 359: 9-13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07272-0.

Castellsague J, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, Varas-Lorenzo C, Fourrier-Reglat A, Nicotra F, Sturkenboom M, Perez-Gutthann S, Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (SOS) Project: Individual NSAIDs and upper gastrointestinal complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies (the SOS project). Drug Saf. 2012, 35: 1127-1146. 10.1007/BF03261999.

Rostom A, Muir K, Dubé C, Jolicoeur E, Boucher M, Joyce J, Tugwell P, Wells GW: Gastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, 5: 818-828. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.011.

Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, Makuch R, Eisen G, Agrawal NM, Stenson WF, Burr AM, Zhao WW, Kent JD, Lefkowith JB, Verburg KM, Geis GS: Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. The CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000, 284: 1247-1255. 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247.

Schnitzer TJ, Burmester GR, Mysler E, Hochberg MC, Doherty M, Ehrsam E, Gitton X, Krammer G, Mellein B, Matchaba P, Gimona A, Hawkey CJ, TARGET Study Group: Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), reduction in ulcer complications: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004, 364: 665-674. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16893-1.

Singh G, Fort JG, Goldstein JL, Levy RA, Hanrahan PS, Bello AE, Andrade-Ortega L, Wallemark C, Agrawal NM, Eisen GM, Stenson WF, Triadafilopoulos G, SUCCESS-I Investigators: Celecoxib versus naproxen and diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients: SUCCESS-1 study. Am J Med. 2006, 119: 255-266. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.054.

Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, Lanas A, Jolicoeur E, Tugwell P: Prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a meta-analysis of unsaid with gastroprotection and COX-2 inhibitors. Drug Health Patient Safety. 2009, 1: 1-25.

Jarupongprapa S, Ussavasodhi P, Katchamart W: Comparison of gastrointestinal adverse effects between cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and non-selective, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs plus proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2012,

Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M, Jüni P: Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011, 342: c7086-10.1136/bmj.c7086.

Fiorucci S, Distrutti E: COXIBs, CINODs and H2S-releasing NSAIDs: current perspectives in the development of safer non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2011, 18: 3494-3505. 10.2174/092986711796642508.

Fries JF, Murtagh KN, Bennett M, Zatarain E, Lingala B, Bruce B: The rise and decline of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-associated gastropathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 2433-2440. 10.1002/art.20440.

Sung JJ, Kuipers EJ, El-Serag HB: Systematic review: the global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009, 29: 938-946. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03960.x.

Sonnenberg A: Time trends of ulcer mortality in Europe. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 2320-2327. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.108.

Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Quintero E, Perez-Aisa MA, Gisbert JP, Bujanda L, Castro M, Muñoz M, Del-Pino MD, Garcia S, Calvet X: The changing face of hospitalisation due to gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 33: 585-591. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04563.x.

Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, Perez-Gisbert J, Bujanda L, Castro M, Muñoz M, Rodrigo L, Calvet X, Del-Pino D, Garcia S: Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009, 104: 1633-1641. 10.1038/ajg.2009.164.

Lanas A, Sopeña F: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and lower gastrointestinal complications. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009, 38: 333-352. 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.03.007.

Lanas A, Perez-Aisa MA, Feu F, Ponce J, Saperas E, Santolaria S, Rodrigo L, Balanzo J, Bajador E, Almela P, Navarro JM, Carballo F, Castro M, Quintero E, Investigators of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG): A nationwide study of mortality associated with hospital admission due to severe gastrointestinal events and those associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005, 100: 1685-1693. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41833.x.

Laine L, Curtis SP, Langman M, Jensen DM, Cryer B, Kaur A, Cannon CP: Lower gastrointestinal events in a double-blind trial of the cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitor etoricoxib and the traditional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug diclofenac. Gastroenterology. 2008, 135: 1517-1525. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.067.

Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA: Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005, 3: 55-59. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00603-2.

Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Theodors A, Gonzalez J, Bjarnason I: A quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005, 128: 1172-1178. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.020.

Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG, Investigators: Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005, 3: 133-141. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00619-6.

Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ: Faecal blood loss with aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors: systematic review of randomized trials using autologous chromiumlabelled erythrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008, 10: R7-10.1186/ar2355.

Smecuol E, Pinto Sanchez MI, Suarez A, Argonz JE, Sugai E, Vazquez H, Litwin N, Piazuelo E, Meddings JB, Bai JC, Lanas A: Low-dose aspirin affects the small bowel mucosa: results of a pilot study with a multidimensional assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009, 7: 524-529. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.019.

Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG: Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005, 3: 133-141. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00619-6.

Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, Berger MF: Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007, 25: 1211-1222. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03312.x.

Chan FK, Lanas A, Scheiman J, Berger MF, Nguyen H, Goldstein JL: Celecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010, 376: 173-179. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60673-3. A published erratum appears in Lancet 2011, 378:228

Hedenbro JL, Wetterberg P, Vallgren S, Bergqvist L: Lack of correlation between fecal blood loss and drug-induced gastric mucosal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998, 34: 247-251.

Morris AJ, Madhok R, Sturrock RD, Capell HA, MacKenzie JF: Enteroscopic diagnosis of small bowel ulceration in patients receiving non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1991, 337: 520-10.1016/0140-6736(91)91300-J.

Lanas A, Panés J, Piqué JM: Clinical implications of COX-1 and/or COX-2 inhibition or the distal gastrointestinal tract. Curr Pharm Des. 2003, 9: 2253-2266. 10.2174/1381612033453992.

Fortun PJ, Hawkey CJ: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005, 21: 169-175. 10.1097/01.mog.0000153314.51198.58.

Bjarnason I, Williams P, Smethurst P, Peters TJ, Levi AJ: Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostaglandins on the permeability of the human small intestine. Gut. 1986, 27: 1292-1297. 10.1136/gut.27.11.1292.

Bjarnason I, Smethurst P, Macpherson A, Walker F, McElnay JC, Passmore AP, Menzies IS: Glucose and citrate reduce the permeability changes caused by indomethacin in humans. Gastroenterology. 1992, 102: 1546-1550.

Smecuol E, Bai JC, Sugai E, Vazquez H, Niveloni S, Pedreira S, Mauriño E, Meddings J: Acute gastrointestinal permeability responses to different non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gut. 2001, 49: 650-655. 10.1136/gut.49.5.650.

Sigthorsson G, Crane R, Simon T, Hoover M, Quan H, Bolognese J, Bjarnason I: COX-2 inhibition with rofecoxib does not increase intestinal permeability in healthy subjects: a double blind crossover study comparing rofecoxib with placebo and indomethacin. Gut. 2000, 47: 527-532. 10.1136/gut.47.4.527.

Bjarnason I, Zanelli G, Smith T, Prouse P, Williams P, Smethurst P, Delacey G, Gumpel MJ, Levi AJ: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal inflammation in humans. Gastroenterology. 1987, 93: 480-489.

Bjarnason I, Zanelli G, Prouse P, Smethurst P, Smith T, Levi S, Gumpel MJ, Levi AJ: Blood and protein loss via small intestinal inflammation induced by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1987, 2: 711-714.

Allison MC, Howatson AG, Torrance CJ, Lee FD, Russell RI: Gastrointestinal damage associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327: 749-754. 10.1056/NEJM199209103271101.

Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P: A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002, 123: 999-1005. 10.1053/gast.2002.35988.

Kurahara K, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Honda K, Yao T, Fujishima M: Clinical and endoscopic features of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic ulcerations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001, 96: 473-480. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03530.x.

Lanas A, Sekar MC, Hirschowitz BI: Objective evidence of aspirin use in both ulcer and non-ulcer upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1992, 103: 862-869.

Lanas A, Serrano P, Bajador E, Esteva F, Benito R, Sáinz R: Evidence of aspirin use in both upper and lower gastrointestinal perforation. Gastroenterology. 1997, 112: 683-689. 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041228.

Laine L, Connors LG, Reicin A, Hawkey CJ, Burgos-Vargas R, Schnitzer TJ, Yu Q, Bombardier C: Serious lower gastrointestinal clinical events with nonselective NSAID or coxib use. Gastroenterology. 2003, 124: 288-292. 10.1053/gast.2003.50054.

Lanas A: Update on gastrointestinal disorders associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008, 31 (SuppL 4): 35-41.

Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, Wu JC, Lee KC, Leung VK, Hui AJ, To KF, Leung WK, Wong VW, Chung SC, Sung JJ: Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2002, 26: 2104-2110.

Laine L, Smith R, Min K, Chen C, Dubois RW: Systematic review: the lower gastrointestinal adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006, 24: 751-767. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03043.x.

Wilcox CM, Alexander LN, Cotsonis GA, Clark WS: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are associated with both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1997, 42: 990-997. 10.1023/A:1018832902287.

Tramèr MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJ, McQuay HJ: Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: a new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain. 2000, 85: 169-182. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00267-5.

Lim CH, Vani D, Shah SG, Everett SM, Rembacken BJ: The outcome of suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding with 24-hour access to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2006, 38: 581-585. 10.1055/s-2006-925313.

Sadic J, Borgström A, Manjer J, Toth E, Lindell G: Bleeding peptic ulcer - time trends in incidence, treatment and mortality in Sweden. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009, 30: 392-398. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04058.x.

Sonnenberg A: Time trends of ulcer mortality in Europe. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 2320-2327. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.108.

Brown TJ, Hooper L, Elliott RA, Payne K, Webb R, Roberts C, Rostom A, Symmons D: A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: a systematic review with economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2006, 10: iii-iv. xi-xiii, 1-183

Lanas A: Editorial: upper GI bleeding-associated mortality: challenges to improving a resistant outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010, 105: 90-92. 10.1038/ajg.2009.517.

Declaration

This article has been published as part of Arthritis Research & Therapy Volume 15 Suppl 3, 2013: 'Gastroprotective NSAIDS'. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://arthritis-research.com/supplements/15/S3. The supplement was proposed by the journal and developed by the journal in collaboration with the Guest Editor. The Guest Editor assisted the journal in preparing the outline of the project but did not have oversight of the peer review process. The Guest Editor serves as a clinical and regulatory consultant in drug development and has served as such consultant for companies which manufacture and market NSAIDs including Pfizer, Pozen, Horizon Pharma, Logical Therapeutics, Nuvo Research, Iroko, Imprimis, JRX Pharma, Nuvon, Medarx, Asahi. The articles have been through the journal's standard peer review process. Publication of this supplement has been supported by Horizon Pharma Inc. Duexis (ibuprofen and famotidine) is a product marketed by the sponsor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

AL is consultant or has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Bayer. CS and CJG declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sostres, C., Gargallo, C.J. & Lanas, A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper and lower gastrointestinal mucosal damage. Arthritis Res Ther 15 (Suppl 3), S3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4175

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4175