Abstract

A detailed study has been performed on the antioxidant activity of the acetone and methanol extracts of the stem bark of the plant, Shorea roxburghii. The total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the extracts were determined by DPPH, radical scavenging, ferric ion reducing power, hydroxyl radical, ABTS. radical scavenging and hydrogen peroxide scavenging activities. Reducing efficiency of the S. roxburghii towards silver nanoparticles has been evaluated using surface plasmon resonance and transmission electron microscope. Spherical shapes of particles with 4–50 nm have been reported. Formation of silver nanoparticles ascertains the role of the water soluble phenolic compounds present in S. roxburghii. Both acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii stem bark was found to be a potent antioxidant. This work provides a scientific support for the high antioxidant activity of this plant and thus it may find potential applications in the treatment of the diseases caused by free radical. The extract of this plant could be used as a green reducing agent for the synthesis of Ag nanoparticles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been intense interest recently among the public and the media in the possibility that increased intake of dietary antioxidants may protect against chronic diseases, which include cancers, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases. Antioxidants are substances that, when present at low concentrations, compared with those of an oxidizable substrate, significantly prevent or delay a pro-oxidant–initiated oxidation of the substrate (Prior and Cao, 1999). A pro-oxidant is a toxic substance that can cause oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, resulting in various pathological events or diseases. Examples of pro-oxidants include reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS), which are products of normal aerobic metabolic processes. ROS include superoxide (O2−·), hydroxyl (OH·), and peroxyl (ROO·) radicals, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). RNS include nitric oxide (NO·) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2·) (Gülçin, 2012; Gülçin et al. 2011). There is a considerable biological evidence that ROS and RNS can be damaging to cells and, thereby, they might contribute to cellular dysfunction and diseases. The existence and development of cells in an oxygen-containing environment would not be possible without the presence of a complicated antioxidant defense system that includes enzymatic and nonenzymatic components. The nonenzymatic antioxidants, most of which have low molecular weights and are able to directly and efficiently quench ROS and RNS, constitute an important aspect of the body’s antioxidant system components (Cao and Prior, 2002). The interaction among these antioxidants and the difficulty in measuring all of them individually prompted the development of assays for measuring total antioxidant capacity. The measurement of total antioxidant capacity of all these nonenzymatic antioxidants is necessary and important in evaluating in vivo antioxidant status in many clinical and nutritional studies.

Shorea roxburghii is a semievergreen endangered tree which grows up to 100 m, fall on the slope of the hill area of peninsular India, which is included in the list of medicinal plants of conservation areas of Eastern and Western Ghats of South India (Rani and Pullaiah, 2002) especially in Kolli Hills of central Tamil Nadu (Matthew, 1999) and some population are distributed in Alagar Hills of Madurai (Karuppusamy et al. 2009). The genus shorea is a rich source for oligomeric stilbenes (Sotheeswaran and Pasupathy, 1993). The bark of S. roxburghii has been used as an astringent or a preservative for traditional beverages in Thailand. In Indian folk medicine, it has been used for treatments of dysentery, diarrhoea, and cholera (Chitravadivu et al. 2009). Previous phytochemical study of the Shorea species revealed the presence of various stilbenoids (Tukiran et al. 2005). Some of these stilbenoids which show interesting biological activities such as cytotoxic (Seo et al. 1999& Aminah et al. 2002), antioxidant (Tanaka et al. 2000; Saisin et al. 2009), antiplatelet aggregation (Aburjai, 2000) and cyclooxygenase inhibitory activities (Li et al. 2001). The aim of the present study is to explore the antioxidant potential of acetone and methanol extracts of stem bark of Shorea roxburghii. DPPH, ABTS, hydroxyl radical and hydrogen peroxide scavenging activities and ferric reducing power assays have been to evaluate the antioxidant activity of these extracts. The reducing ability of water extract towards Ag nanoparticles has been also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical and ABTS radicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Bangalore, India. Gallic acid, trichloroacetic acid, potassium ferricyanide, ferric chloride, aluminium chloride, Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (phenol reagent), methanol, sodium carbonate, sodium hydroxide, sodium nitrite, ammonium acetate, acetone, glacial acetic acid, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), ferrous ammonium sulphate, EDTA, DMSO, potassium persuphate and silver nitrate (AgNO3) were procured from Merck, India. All chemicals used were of analytical grade and used as such without further purification. All the solutions were prepared with Millipore water.

Plant collection and preparation of crude extract

Stem bark of Shorea roxburghii was collected from Alagar Hills, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India during March 2010. The plant materials were dried under shade, pulverized and used for the preparation of crude extract. 50 g of powdered stem bark materials of S. roxburghii in the thimble were introduced into double bypass soxhlet apparatus (DBSA) which was connected with two distillation flasks through inverted Y shaped joints and extracted with 500 mL of acetone and methanol (Subramanian et al. 2011). The extracts were evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator. The obtained acetone (8 g) and methanol 6 (g) crude extracts were used for the measurements of total phenolic content and antioxidant activities. 20 g of powdered stem bark of S. roxburghii was extracted with boiling water for 30 min and evaporated to dryness in a water bath. The obtained crude extract was used for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles.

Total phenolic content

Total phenolic content of acetone and methanol extracts of stem bark of S.roxburghii was determined by the method of Singletone and Rossi, 1965. 10 mg of individual plant extract was dissolved in methanol to get the appropriate concentration (1 mg/mL). 1.0 mL of each extract in a test tube was mixed with 5.0 mL of distilled water. 1.0 mL of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent was added and mixed thoroughly. 3 min later, 3.0 mL of saturated sodium carbonate solution was added and the mixture was allowed to stand for 90 min in the dark. The absorbance of the color developed was read at 725 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The concentration of total phenolic content in the extracts was determined as μg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) by calibration curve (r2=0.989). Three replicates were performed for each sample concentration to check the reproducibility of the experimental result and to get a more accurate result. The results were represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Antioxidant activity assay

DPPH radical scavenging activity

Various concentrations (20, 40, 60, 80 & 100 μg/mL) of extracts were mixed with 3.0 mL of methanolic solution containing DPPH radical (6×10-5 mol/L). The mixture was shaken vigorously and left to stand for 60 min in the dark. The reduction of the DPPH radical was determined by recording the absorbance at 517 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer. DPPH radical-scavenging activity was calculated by the following equation:

where ADPPH is the absorbance without samples and As the absorbance in the presence of the samples. A lower absorbance of the reaction mixture indicated a higher DPPH radical-scavenging activity (Gülçin, 2003; Gülçin, 2011).

Ferric reducing power

Exactly 1 mL of the extract was mixed with 2.5 mL of phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 2.5 mL of potassium ferricyanide (1%). The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min. Afterwards, 2.5 mL of trichloroacetic acid (10%) was added to the mixture, which was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Finally, 2.5 mL of the upper layer was pipetted out and mixed with 2.5 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of ferric chloride (0.1%) was added. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer. The intensity of reducing power is directly proportional to the absorbance of the reaction mixture (Barrors et al. 2007; Yildirim et al. 2001).

Hydrogen peroxide radical scavenging activity

The ability of the extracts to scavenge hydrogen peroxide was determined according to the method of Cetinkaya et al. 2012. Hydrogen peroxide solution (1 mM/L) was prepared with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Different concentrations (20–100 μg) of the extracts (1 mL) were allowed to react with 0.6 mL of hydrogen peroxide solution. Absorbance was determined at 230 nm after 10 min against a blank solution containing phosphate buffer without hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity was calculated according to the following equation:

where Ac is the absorbance without samples and As is the absorbance in the presence of the samples.

ABTS radical scavenging activity

ABTS radical scavenging activity was estimated by the method of Bursal and Gülçin 2011and Gülçin et al. 2010. The stock solutions included 7 mM ABTS solution and 2.4 mM potassium persuphate solution. The working solution was then prepared by mixing the two stock solutions in equal quantities and allowing them to react for overnight at room temperature in the dark. The solution was then diluted by mixing 1 mL of ABTS solution with 60 mL ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.706 ± 0.001 units at 734 nm. Fresh ABTS solution was prepared for each assay. Different concentrations (20–100 μg) of the extracts (1 mL) were allowed to react with 1 mL of the ABTS solution and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm after 7 min using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer. ABTS radical scavenging activity was calculated according to the following equation:

where Ac is the absorbance without samples and As the absorbance in the presence of the samples.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of the extracts was carried out by the method of Halliwell and Gutteridge 1981. Exactly, 0.2 mL of the extract was added with 1.0 mL of EDTA solution (0.13 g of ferrous ammonium sulphate and 0.26 g of EDTA were dissolved in 100 mL of water) and mixed with 1.0 mL of DMSO (0.85%) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to initiate the reaction followed by the addition of 0.5 mL of 0.22% ascorbic acid. The reaction mixture was kept in a water bath at 90°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated by adding 1.0 mL of ice-cold 17.5% trichloroacetic acid. Further 3.0 mL of Nash reagent (75 g of ammonium acetate, 3.0 mL of glacial acetic acid and 2.0 mL of acetyl acetone in 1.0 L of water) was added to all the test tubes and incubated for 15 min for color development. The absorbance was observed at 412 nm. The reaction mixture without ascorbic acid served as control. The ability to scavenge hydroxyl radical was calculated by the following equation:

where Ac is the absorbance without samples and Ae the absorbance in the presence of the samples.

EC50 value (μg extract/mL) is the effective concentration at which the reducing power, hydrogen peroxide, DPPH, ABTS radical and hydroxyl radical scavenging activities were scavenged by 50% and were obtained by interpolation from linear regression analysis. Vitamin C was used as a standard.

Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles

Reducing ability of the stem bark extract of S.roxburghii in the formation of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from silver nitrate was tested using S. roxburghii as reducing and capping agent. 20 g of the powdered stem bark of S. roxburghii was boiled in water and used as reducing agent. Various concentrations of extract (1.0, 2.5, 3.5 and 5.0 mL) were added drop wise to 50 mL of silver nitrate solution (1.0 mM) with constant stirring. The kinetics of the reaction was monitored by measuring the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of the reaction mixture at different time intervals by UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The shape and size of the particles were measured with high resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using JEOL JEM-100CX II equipped with selected area electron diffraction pattern (SAED).

Statistical analysis

Triplicate analysis were performed by excel sheet. The results were presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed using student’s t-test and a P < 0.05 was regarded to be significant.

Results and discussion

Total phenol content

The amount of total phenols present in acetone and methanol extract of stem bark of S.roxburghii was determined from the regression equation (y = ax + b) of calibration curve of gallic acid standard solution and expressed in gallic acid equivalents (Figure 1). Total phenolic content of acetone (65.74 ± 8.70 μg/mL) and methanol (67.67 ± 4.90 μg/mL) extracts were found to be similar. From the results it can be seen that the extraction ability of acetone and methanol are very similar to one another. Phenolics are secondary plant metabolites that are present in every plant and plant product. Many of the phenolics have been shown to contain high levels of antioxidant activities. Phenolic compounds present in the plants acting as antioxidant or free radicals scavengers (Kahkonen et al. 1999) due to their hydroxyl groups which contribute directly to the antioxidative action (Diplock, 1997). Phenolic compounds are effective hydrogen donors, making them good antioxidants (Rice-Evan and Miller 1997).

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The radical-scavenging activity of the acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii was estimated by comparing the percentage inhibition of formation of DPPH radicals with that of vitamin C. Both acetone and methanol extracts showed moderate antioxidant activity when compared with Vitamin C. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of acetone and methanol extracts increased with increasing the concentration (Table 1). Our results were in agreement with Ragini et al. 2011who reported radical scavenging activity of 23.40, 34.50, 48.67, 65.40 and 79.50% in ethanolic extract of Shorea tumbuggaia at a concentration of 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μg/mL, respectively. Natural antioxidants those are present in medicinal plants which are responsible for inhibiting the harmful consequences of oxidative stress. Many plants extract exhibit efficient antioxidant properties due to their phytoconstituents, including phenolics (Larson, 1988). This method has been extensively used for screening antioxidants, such as polyphenols. The antioxidant effectiveness in natural sources has been reported to be mostly due to phenolic compounds. Phenolic compounds may contribute directly to antioxidative effect of the extracts. The free radical scavenging activity of acetone and methanolic extracts were confirmed in the present investigation.

DPPH is a stable free radical at room temperature and accepts an electron or hydrogen radical to become stable diamagnetic molecules (Soares et al. 1997). This method has been extensively used for screening antioxidants, such as polyphenols. DPPH radical is scavenged by polyphenols through donation of hydrogen, forming the reduced form of DPPH. Then the colour changes from purple to yellow after reduction, which can be quantified by its decrease absorbance at wavelength 517 nm (Amarowicz et al. 2004; Bondet et al. 1997). The decrease in absorbance of DPPH radical caused by antioxidants, because of the reaction between antioxidant molecule and radical progresses, results in the scavenging of the radical by hydrogen donation. It is visually noticeable as a discoloration from purple to yellow. These results revealed that the acetone and methanol extracts of S roxburghii is free radical inhibitor or scavenger acting possibly as primary antioxidants.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Hydroxyl radical inhibition of S. roxburghii was investigated and these results are shown as relative activity against the standard (Vitamin C). Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of S. roxburghii is presented in Table 1. There is no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the hydroxyl radical scavenging activities of the acetone and methanol extracts, showing that these extracts are equally potent in scavenging hydroxyl radicals. The extracts were less effective in comparison with vitamin C. IC50 values were 52.56 and 50.93 μg/mL, whereas that of vitamin C was 45.91 μg/mL. Dose-dependent hydroxyl radical scavenging activity reveals that, acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii have potent hydroxyl radical scavengers, acting possibly as primary antioxidants. Hydroxyl radical is an extremely reactive free radical formed in biological system and has been implicated as a highly damaging species in free radical pathology, capable of damaging almost every molecule, proteins, DNA, unsaturated fatty acids and lipids in almost every biological membranes found in living cells (Hochestein and Atallah, 1988; Rollet-Labelle et al. 1998; Trease and Evans, 1983).

ABTS Radical scavenging activity

Both acetone and methanol extracts showed comparable scavenging effects on ABTS·+. The extracts were less effective in comparison with vitamin C. The ABTS radical scavenging activity of the acetone extract (20.77, 45.07, 56.13, 65.20 and 79.20%) was comparable with that of methanol extract (19.60, 36.27, 58.13, 64.40 and 86.27%). IC50 values for acetone and methanol extracts were 55.24 and 55.96 μg/mL, respectively whereas that of vitamin C was 43.05 μg/mL (Table 1). The results clearly imply that the acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii inhibit ABTS radical or scavenge the radical in a dose dependent manner. ABTS·+ radical is generated from oxidation of ABTS·+ by potassium persulphate, is a good tool for determining the antioxidant activity of hydrogen-donating and chain breaking antioxidants (Leong and Shui, 2002). This assay is applicable for both lipophilic and hydrophilic antioxidants. The radical-scavenging activity of the acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii were estimated by comparing the percentage inhibition of formation of ABTS·+ radicals with that of vitamin C. These extracts exhibited the highest radical-scavenging activities when reacted with the ABTS radicals.

Hydrogen peroxide radical scavenging activity

The hydrogen peroxide radical-scavenging activity of the acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii was estimated by comparing the percentage inhibition of formation of peroxyl radicals with that of vitamin C. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity of acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii are presented in Table 1. Both acetone and methanol extracts showed moderate inhibition against peroxyl radical which was less in comparison with vitamin C. These results showed that acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii are highly potent in neutralizing hydrogen peroxide radicals. Most of the hydrogen peroxide was scavenged by the extracts. IC50 values for acetone and methanol extracts were 87.18 and 63.67 μg/mL, respectively whereas that of Vitamin C was 28.53 μg/mL. H2O2 itself is not very reactive, but it can sometimes be toxic to cell because it may give rise to hydroxyl radical in the cells. The results showed that S. roxburghii extracts have an effective H2O2 scavenging activity.

Ferric reducing power

In the reducing power assay, the presence of antioxidants in the extract of S. roxburghii would result in the reduction of Fe3+/ferricyanide complex to its form. The reducing power of compound may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity (Meir et al. 1995). The ferric reducing power of the acetone and methanol extracts of S. roxburghii was determined by comparing with that of vitamin C. The increased absorbance values of the extracts at 700 nm indicate an increase in reductive ability. Absorbance values of acetone and methanol extracts are presented in Table 1. Ferric reducing power increasing the absorbance values Absorbance values of acetone and methanol extracts are presented in Table 1. The reducing power of ascorbic acid was found to be significantly higher than those of acetone and methanol extracts. In this assay, the yellow color of the test solution was changed to various shades of green and blue depending on the reducing power of each compound. At 1000 μg/mL, the reducing powers of the acetone and methanol extract were 0.078–0.378 and 0.139–0.479, respectively whereas that of vitamin C was 0.216–0.918. The reducing power increased with increasing the phenolic content of the extract. It was found that the reducing powers of all the extracts also increased with the increase of their concentrations. This data imply that these extracts have significant ability to react with free radicals to convert them into more stable nonreactive species and to terminate radical chain reaction.

Numerous methods are available to evaluate of antioxidant activity. For in vitro antioxidant screening, DPPH, ABTS, hydroxyl radical scavenging, hydrogen peroxide scavenging activities and ferric reducing power are most commonly used. However, the total antioxidant activity of an antioxidant cannot be evaluated by using one single method, due to oxidative processes. Therefore, at least two methods should be employed in order to evaluate the total antioxidant activity (Gulcin et al. 2005). Present study was undertaken to demonstrate the antioxidant capacity of stem bark extract of S. roxburghii by vitro methods. Shorea species are well known for its phenolic content and antioxidant activities. Norizan et al. (2012) have reported the phenolic content of Shorea acuminate, Shorea leprosula, Shorea resinosa, Shorea macroptera and Shorea bracteolate (2731, 2615, 2461, 2461 and 2423 mg/100 g). Similarly they reported the total antioxidant property of the methanol extracts in the following order: Shorea macroptera> Shorea leprosula> Shorea resinosa> Shorea acuminate>Shorea bracteolate at 98.68, 78.42, 71.11, 57.47 and 56.75%, repscetively. Recently, Wani et al. (2012) reported the wound healing capacity of ethanolic extract of Shorea robusta. Shorea species are rich in stilbenes which are made up of resveratrol derivatives, are highly bioactive compounds. Many authors have reported several bioactive phenolic compounds from S. roxburghii. Roxburghiol A, Melanoxylin A, Caragaphenol A, (−)-ε-viniferin, Hopeahainanphenol, Vitisinol G, Vaticanol A, (−)-hopeaphenol, Isohopeaphenol, Apigenin 7-O-arabinoside, trans-piceid, and trans-3, 5, 4′-trihydroxy resveratrol 2-C-glucoside from the bark of S. roxburghii has been reported by Patcharamun et al. 2011isolated. Similarly, Morikawa et al. (Morikawa et al. 2012& Morikawa et al. 2012) have reported resveratrol, piceid, trans-resveratrol 10 C-β-D-glucopyranoside, Cis-resveratrol 10-C-ß-D-gluco pyranoside, Phayomphenols A1, Phayomphenols A2, S-Dihydrophayomphenol A2, Phayomphenol B1, Phayomphenol B2 (3), (−)-Ampelopsin A, Hopeafuran, (−)-Balanocarpol, Malibatols A, Malibatol B, Vaticanol A, Vaticanol E, Vaticanol G, (+)-Parviflorol. (−)-α-Viniferin, (−)-Ampelopsin H and Hemsleyanol D. Resveratrol and its derivatives are powerful antioxidants (Pour Nikfardjam et al. 2006). This much higher activity may be due to the presence of above mentioned high molecular weight phenolic compounds which are resveratrol derivatives, have number of aromatic rings and hydroxyl groups. With respect to biological activities, only scared studies are undertaken in Shorea roxburghii. It can be seen that, the solvents acetone and methanol are suitable for extraction of antioxidant compounds present in S. roxburghii since the radical scavenging activity of acetone and methanol extracts are similar.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles has drawn much attention due to its vast application in various fields. Silver nanoparticles are used in the field of magnetics, optoelectronics, information storage (Okuda et al. 2005; Dai and Bruening, 2002; Murray et al. 2001), catalysis (Watanabe et al. 2006), biosensing, imaging, drug delivery, nanodevice fabrication and medicine (Nair and Laurencin, 2007; Lee and El-Sayed, 2006; Jain et al. 2008). Various methods such as chemical (Sun et al. 2002), electrochemical (Yin et al. 2003), radiation (Dimitrijevic et al. 2001, photochemical (Callegari et al. 2003) and biological methods (Naik et al. 2002) are preferred for synthesis of silver nanoparticles. The biosynthetic method employing plant extracts has drawn attention as a simple and viable alternative to chemical procedures and physical methods. Even though numbers of physical and chemical methods are available for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles, they could create problems owing to the use of toxic solvents, generation of by-products and high energy consumption. Hence, there is a constant search to develop environmentally benign procedures for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Recently, Murraya koenigii leaf (Philip et al. 2011), Mangosteen leaf (Veerasamy et al. 2011), Mangifera indica leaf (Philip, 2011), Tansy fruit (Dubey et al. 2010), Jatropha curcas (Bar et al. 2009), Cinnamomum zeylanicum leaf (Smitha et al. 2009), Camellia sinensis (Nestor et al. 2008), Aloe vera (Chandran et al. 2006), Mushroom extracts (Philip, 2009) and Honey (Philip, 2009) have been used for the synthesis of metal nanoparticles.

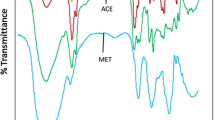

The kinetics of the reaction between silver ions and stem bark extracts of S. roxburghii was monitored by recording the absorption spectra as a function of time. By employing the variable volume of extract (1.0, 2.5, 3.5 and 5.0 mL) with 1.0 mM silver nitrate, the effect of concentrations of the extract on the rate of bioreduction was studied. Adding separately different volume of extract of S. roxburghii to the silver nitrate solution, a characteristic sharp surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band was appeared from 412–432 nm indicating the formation of Ag nanoparticles.

Figure 2 (A-D) show the UV-Visible absorption spectrum of the AgNPs as a function of the concentrations, 1.0, 2.5, 3.5 and 5 mL of extract with 1 mM AgNO3. Neither yellowish-brown color change in the reaction vessel nor a strong plasmon resonance peak was observed for the silver nitrate solution, which was mixed with the water extract of S. roxburghii at 0 h. Upon addition of the extract to the silver nitrate solution, the color of the solution was changed from yellow to brown due to the reduction of Ag+ to metallic Ag0. It is well known that silver nanoparticles exhibit yellowish brown color in water, which arises due to the excitation of surface plasmon resonance in the metal nanoparticles (Nand and Saravanan, 2009). The relationship between the surface plasmon resonance, metal nanoparticle’s size and shape is well established (Wiley et al. 2006). Metal nanoparticles such as silver have free electrons, which give rise to surface plasmon resonance absorption band (Noginov et al. 2006). Consequently size and shape of nanoparticles in aqueous suspension can be judged by UV-visible absorbance studies. This important observation indicates that the reduction of the Ag+ ions takes place in the extract of S .roxburghii under visible-light irradiation. The increase in intensity is due to increasing the concentration of silver nanoparticles formed as a result of reduction of silver ions present in the aqueous solution.

Upon addition of 1.0 mL of extract with 1 mM silver nitrate solution, λmax or intensity was observed at 24 h followed by 48 and 120 h. The lower volume of extracts (1.0 & 2.5 mL) was insufficient to produce AgNPs as it requires 24 h to reduce the silver ions. Nucleation of silver nanopaticles was started only after 2 h during the addition of 3.5 and 5.0 mL of extract which was found to adequate to reduce the silver ions. The concentrations, 3.5 and 5.0 mL of extract was sufficient to produce the silver nanoparticles, but there was a sharp difference between these two particularly with respect to intensity. SPR peak resulted from 5.0 mL extract has high intensity (1.229 a.u) whereas 3.5 mL has low intensity (1.000 a.u). The high intensity of the peak is due to the high concentration of silver nanoparticles. From the UV-Visible studies, it has been found that the amount of the extract has played a vital role in the formation of AgNPs. It has been proved that 5.0 mg of the extract is enough to produce silver nanoparticles. The TEM analysis was also carried out for AgNPs synthesized using 5.0 mL of extract to find out the shape and size of the particles. Figure 3 (A), (B), (C) and (D) depict the typical TEM images of synthesized AgNPs. These pictures exhibit that the majority of the particles are in spherical shape with smooth surfaces. Figure 3 (F) shows the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and suggests the polycrystalline nature of the green synthesized AgNPs. The TEM image represents the frequency of TEM size distribution of AgNPs ranging from 4–50 nm.

The reducing capacity depends on the amount of water soluble phenolic compound present in the extract. During the reaction with silver nitrate, the phenolic compound donates electron to Ag+ to produce Ag0. After donation of an electron, the phenolic compounds changed into quinine which is stabilized by the resonance structure of the same. The bioreduction of silver ions and the formation of AgNPs are closely related to the biomolecular component of the extract. Biosynthesis is a green process, no by-products and wastage formed during the reaction. Several authors reported green synthesis using various medicinal plants with different shape and sizes.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the stem bark extracts of Shorea roxburghii contain high level of total phenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity. Acetone extract showed highest scavenging activities against DPPH and hydroxyl radicals. Methanol extract showed highest activities against ABTS, hydrogen peroxide radicals and ferric reducing power. The stem bark extract of S. roxburghii can be explored for its applications in the prevention of free radical related diseases.

Shorea roxburghii stem bark extract have been effectively used for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. We have demonstrated the use of a natural, renewable and low-cost bioreducing agent. This plant extract could be used as an efficient green reducing agent for the production of AgNPs. The spectroscopic characterization from UV-Visible and TEM supports the stability of the biosynthesized nanoparticles. The size of the particles is found to be 4–50 nm.

References

Aburjai TA: Anti-platelet stilbenes from aerial parts of Rheum palaestinum . Phytochemistry 2000, 55: 407-410. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00341-1

Amarowicz R, Pegg RB, Rahimi-Moghaddam P, Barl B, Weil JA: Free radical- scavenging capacity and antioxidant activity of selected plant species from the Canadian prairies. Food Chem 2004, 84: 551-562. 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00278-4

Aminah NS, Achmad SA, Aimi N, Ghisalberti EL, Hakim EH, Kitajima M, Syah YM, Takayama H: Diptoindonesin A, a new C-glucoside of ε-viniferin from Shorea seminis (Dipterocarpaceae). Fitoterapia 2002, 73: 501-507. 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00179-X

Bar H, Bhui DK, Sahoo GP, Sarkar P, De SP, Misra A: Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex of Jatropha curcas . Colloids Surf A 2009, 339: 134-139. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.02.008

Barrors L, Baptissa P, Ferreira ICFR: Effect of Lactarius piperatus fruiting body maturity stage on antioxidant activity measured by several biochemical assays. Food Chem Toxicol 2007, 45: 1731-1737. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.03.006

Bondet V, Brand-Williams W, Berset C: Kinetics and mechanism of antioxidant activity using the DPPH free radical method. LWT- Food Sci Technol 1997, 30: 609-615. 10.1006/fstl.1997.0240

Bursal E, Gülçin İ: Polyphenol contents and in vitro antioxidant activities of lyophilized aqueous extract of kiwifruit ( Actinidia deliciosa ). Food Res Int 2011, 44: 1482-1489. 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.03.031

Callegari A, Tonti D, Chergui M: Photochemically grown silver nanoparticles with wavelength controlled size and shape. Nano Lett 2003, 3: 1565-1568. 10.1021/nl034757a

Cao G, Prior RL: Hand book of Antioxidants. In Measurement of total antioxidant capacity in nutritional and clinical studies, CRC Press. 2nd edition. Edited by: Cadenas E, Packer L. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2002:1-2.

Cetinkaya Y, Göçer H, Menzek A, Gülçin I: Synthesis and antioxidant properties of (3,4- dihydroxyphenyl)(2,3,4-trihydroxyphenyl) methanone and its derivatives. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2012, 345: 323-334. 10.1002/ardp.201100272

Chandran SP, Chaudhary M, Pasricha R, Ahmad A, Sastry M: Synthesis of gold nanotriangles and silver nanoparticles using Aloevera plant extract. Biotechnol Prog 2006, 22: 577-583. 10.1021/bp0501423

Chitravadivu C, Bhoopathi M, Balakrishnan V, Elavazhagan T, Jayakumar S: Antimicrobial activity of laehiums prepared by herbal venders, South India. Am Eur J Sci Res 2009, 4: 142-147.

Dai J, Bruening ML: Catalytic nanoparticles formed by reduction of metal ions in multilayered polyelectrolyte films. Nano Lett 2002, 2: 497-501. 10.1021/nl025547l

Dimitrijevic NM, Bartels DM, Jonah CD, Takahashi K, Rajh T: Radiolytically induced formation and optical absorption spectra of colloidal silver nanoparticles in supercritical ethane. J Phy Chem B 2001, 105: 954-959. 10.1021/jp0028296

Diplock AT: Will the good fairies please prove to us that vitamin E lessens human degenerative disease? Free Radic Res 1997, 27: 511-532.

Dubey SP, Lahtinen M, Sillanpaa M: Tansy fruit mediated greener synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles. Process Biochem 2010, 45: 1065-1071. 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.03.024

Gülçin İ: Antioxidant activity of eugenol: a structure-activity relationship study. J Med Food 2011, 14: 975-985. 10.1089/jmf.2010.0197

Gülçin İ: Antioxidant activity of food constituents: an overview. Arch Toxicol 2012, 86: 345-391. 10.1007/s00204-011-0774-2

Gülçin İ, Buyukokuroglu ME, Kufrevioglu OI: Metal chelating and hydrogen peroxide scavenging effects of melatonin. J Pineal Res 2003, 34: 278-81. 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.00042.x

Gulcin I, Alici HA, Cesur M: Determination of in vitro antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of propofol. Chem Pharm Bull 2005, 53: 281-285. 10.1248/cpb.53.281

Gülçin İ, Bursal E, Sehitog˘ lu MH, Bilsel M, Gören AC: Polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of lyophilized aqueous extract of propolis from Erzurum, Turkey. Food Chem Toxicol 2010, 48: 2227-2238. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.053

Gülçin İ, Topal F, Çakmakçı R, Bilsel M, Gören AC, Erdogan U: Pomological features, nutritional quality, polyphenol content analysis, and antioxidant properties of domesticated and 3 wild ecotype forms of raspberries ( Rubus idaeus L .). J Food Sci 2011, 76: C585-C593. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02142.x

Halliwell B, Gutteridge J: Formation of thiobarbituric-acid-reactive substances from deoxyribose in the presence of iron salts. The role of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals. FEBS Lett 1981, 128: 347-352. 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80114-7

Hochestein P, Atallah AS: The nature of oxidant and antioxidant systems in the inhibition of mutation and cancer. Mutation Res 1988, 202: 363-375. 10.1016/0027-5107(88)90198-4

Jain PK, Huang X, El-Sayed IH, EL-Sayed MA: Noble metals on the nanoscale: optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Acc Chem Res 2008, 41: 1578-1586. 10.1021/ar7002804

Kahkonen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ, Pihlaja K, Kujala TS, Heinonen M: Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem 1999, 47: 3954-3962. 10.1021/jf990146l

Karuppusamy S, Muthuraja G, Rajasekaran KM: Lesser known ethnomedicinal plants of Alagar Hills, Madurai District of Tamil Nadu, India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets 2009, 13: 1426-1433.

Larson RA: The antioxidant of higher plants. Phytochemistry 1988, 27: 969-978. 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80254-1

Lee KS, El-Sayed MA: Gold and silver nanoparticles in sensing and imaging: sensitivity of plasmon response to size, shape, and metal composition. J Phy Chem B 2006, 110: 19220-19225. 10.1021/jp062536y

Leong LP, Shui G: An investigation of antioxidant capacity of fruits in Singapore markets. Food Chem 2002, 76: 69-75. 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00251-5

Li XM, Wang YH, Lin M: Stilbenoids from the lianas of Gnetum pendulum . Phytochemistry 2001, 58: 591-604. 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00269-2

Matthew KM: The Flora of the Palni hills, Part-I The Rapinat Herbarium. Tiruchirapalli, India: St. Joseph’s College; 1999:494.

Meir S, Kanner J, Akiri B, Hadas SP: Determination and involvement of aqueous reducing compounds in oxidative defense systems of various senescing leaves. J Agric Food Chem 1995, 43: 1813-1817. 10.1021/jf00055a012

Morikawa T, Chaipech S, Matsuda H, Hamao M, Umeda Y, Sato H, Tamura H, Ninomiya K, Yoshikawa M, Pongpiriyadacha Y, Hayakawa T, Muraoka O: Antidiabetogenic oligostilbenoids and 3-ethyl-4-phenyl-3,4-dihydroisocoumarins from the bark of Shorea roxburghii . Bioorg Med Chem 2012, 20: 832-840. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.067

Morikawa T, Chaipech S, Matsuda H, Hamao M, Umeda Y, Sato H, Tamura H, Ninomiya K, Yoshikawa M, Pongpiriyadacha Y, Hayakawa T, Muraoka O: Anti-hyperlipidemic constituents from the bark of Shorea roxburghii . J Nat Med 2012, 66: 516-524. 10.1007/s11418-011-0619-6

Murray CB, Sun S, Doyle H, Betley T: Monodisperse 3d transition metal (Co, Ni, Fe) nanoparticles and their assembly into nanoparticle superlattices. MRS Bull 2001, 26: 985-991. 10.1557/mrs2001.254

Naik RR, Stringer SJ, Agarwal G, Jones S, Stone MO: Biomimetic synthesis and patterning of silver nanoparticles. Nature Mater 2002, 1: 169-172.

Nair LS, Laurencin CT: Silver nanoparticles: synthesis and therapeutic applications. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2007, 3: 301-316. 10.1166/jbn.2007.041

Nand A, Saravanan M: Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Staphylococcus aureus and its antimicrobial activity against MRSA and MRSE. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2009, 5: 452-456. 10.1016/j.nano.2009.01.012

Nestor ARV, Mendieta VS, Lopez MAC, Espinosa RMG, Lopez MAC, Alatorre JAA: Solventless synthesis and optical properties of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Camellia sinensis extract. Mater Lett 2008, 62: 3103-3105. 10.1016/j.matlet.2008.01.138

Noginov MA, Zhu G, Bahoura M, Adegoke J, Small CE, Ritzo BA, Drachev VP, Shalaev VM: Enhancement of surface plasmons in an Ag aggregate by optical gain in a dielectric medium. Optics Lett 2006, 31: 3022-3024. 10.1364/OL.31.003022

Norizan N, Ahmat N, Mohamad SAS, Mohd Nazri NAA, Akmar Ramli SS, Mohd Kasim SN, Mohd Zain WZW: Total Phenolic Content, Total Flavonoid Content, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Malaysian Shorea. Res J Med Plant 2012, 6: 489-499. 10.3923/rjmp.2012.489.499

Okuda M, Kobayashi Y, Suzuki K, Sonoda K, Kondoh T, Wagawa A, Kondo A, Yoshimura Y: Self-organized inorganic nanoparticle arrays on protein lattices. Nano Lett 2005, 5: 991-993. 10.1021/nl050556q

Patcharamun W, Sichaema J, Siripong P, Khumkratok S, Jong-aramruang J, Tip-pyang S: A new dimeric resveratrol from the roots of Shorea roxburghii . Fitoterapia 2011, 82: 489-492. 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.01.003

Philip D: Biosynthesis of Au, Ag and Au–Ag nanoparticles using edible mushroom extract. Spectrochimica Acta A 2009, 73: 374-381. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.02.037

Philip D: Honey mediated green synthesis of gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim Acta A 2009, 73: 650-653. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.03.007

Philip D: Mangifera Indica leaf-assisted biosynthesis of well-dispersed silver nanoparticles. Spectrochimica Acta Part A 2011, 78: 327-331. 10.1016/j.saa.2010.10.015

Philip D, Unni C, Aswathy Aromal S, Vidhu VK: Murraya koenigii leaf-assisted rapid green synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim Acta Part A 2011, 78: 899-904. 10.1016/j.saa.2010.12.060

Pour Nikfardjam MS, Gy L, Dietrich H: Resveratrol-derivatives and antioxidative capacity in wines made from botrytized grapes. Food Chem 2006, 96: 74-79. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.058

Prior RL, Cao G: In vivo total antioxidant capacity: comparison of different analytical methods. Free Rad Biol Med 1999, 27: 1173-1181. 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00203-8

Ragini V, Prasad KVSRG, Bharathi K: Antidiabetic and antioxidant activity of Shorea tumbuggaia Rox . Int J Innovat Pharma Res 2011, 2: 113-121.

Rani S, Pullaiah T: A Taxonomic survey of trees in Eastern Ghats. In Proceedings of the National Seminar on Conservation of Eastern Ghats, March 24-26. Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India: S.V. University; 2002:5-15.

Rice-Evan CA, Miller N: Antioxidant property of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci 1997, 2: 152-159. 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01018-2

Rollet-Labelle E, Grange MJ, Elbim C, Marquetty C, Goqgerot-Pocidalo MA, Pasquier C: Hydroxyl radical as a potential intracellular mediator of polymorphonuclear neutrophil apoptosis. Free Rad Biol Med 1998, 24: 563-572. 10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00292-X

Saisin S, Tip-Pyang S, Phuwapraisirisan P: A new antioxidant flavonoid from the lianas of Gnetum macrostachyum . Nat Prod Res 2009, 23: 1472-1477. 10.1080/14786410802280943

Seo EK, Chai HB, Constant HL, Santisuk T, Reutrakul V, Beecher CWW, Farnsworth R, Cordell GA, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD: Resveratrol tetramers from Vatica diospyroides . J Org Chem 1999, 64: 6976-6983. 10.1021/jo9902087

Singletone VL, Rossi JA Jr: Colorimetric of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic- phosphotungestic acid reagents. Am J Enol Viticult 1965, 16: 144-158.

Smitha SL, Philip D, Gopchandran KG: Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Cinnamomum zeylanicum leaf broth. Spectrochim Acta Part A 2009, 74: 735-739. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.08.007

Soares JR, Dinis TCP, Cunha AP, Almeida LM: Antioxidant activities of some extracts of Thymus zygi. Free Rad Res 1997, 26: 469-478. 10.3109/10715769709084484

Sotheeswaran S, Pasupathy V: Distribution of resveratrol oligomers in plants. Phytochemistry 1993, 32: 1083-1092. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)95070-2

Subramanian R, Subbramaniyan P, Raj V: Double bypasses soxhlet apparatus for extraction of piperine from Piper nigrum . Arabian J Chem 2011., 2011: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2011.06.022

Sun Y, Yin Y, Mayers BT, Herricks T, Xia Y: Uniform silver nanowire synthesis using AgNO3 with ethylene glycol in the presence of seeds and poly (vinyl pyrolidine). Chem Mater 2002, 14: 4736-4745. 10.1021/cm020587b

Tanaka T, Ito T, Nakaya K, Iinuma M, Takahashi Y, Naganawa H, Matsuura N, Ubukata M: Vaticanol D, a novel resveratrol hexamer isolated from Vatica rassak . Tetrahedron Lett 2000, 41: 7929-7932. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01383-6

Trease GE, Evans MC: Textbook of Pharmacognosy. 12th edition. London: Balliere, Tindall; 1983:343-383.

Tukiran SA, Euis H, Lukman M, Kokki S, Kuniyoshi S, Yana M: Oligostilbenoids from Shorea balangeran . Biochem Syst Ecol 2005, 33: 631-634. 10.1016/j.bse.2004.10.016

Veerasamy R, Xin TZ, Gunasagaran S, Xiang TFW, Yang EFC, Jeyakumar N, Dhanaraj SA: Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using mangosteen leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. J Saudi Chem Soc 2011, 15: 113-120. 10.1016/j.jscs.2010.06.004

Wani TA, Chandrashekara HH, Kumar D, Prasad R, Gopal A, Sardar KK, Tandan SK, Kumar D: Wound healing activity of ethanolic extract of Shorea robusta Gaertn. resin. Indian J Exp Biol 2012, 50: 277-281.

Watanabe K, Menzel D, Nilius N, Freund HJ: Photochemistry on metal nanoparticles. Chem Rev 2006, 106: 4301-4320. 10.1021/cr050167g

Wiley BJ, Im SH, Li ZY, McLellan J, Siekkinen A, Xia Y: Maneuveering the surface plasmon resonance of silver nanostructures through shape-controlled synthesis. J Phy Chem B 2006, 10: 15666-15675.

Yildirim A, Mavi A, Kara AA: Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L extracts. J Agric Food Chem 2001, 49: 4083-4089. 10.1021/jf0103572

Yin B, Ma H, Wang S, Chen S: Electrochemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles under protection of poly (N-vinylpyrrolidone). J Phy Chem B 2003, 107: 8898-8904. 10.1021/jp0349031

Acknowledgements

One of the authors, R.S thank Dr. Tushar Jana’s Research Group, School of Chemistry, University of Hyderabad, India for providing facilities to carry out the research under the UGC Network Resource Centre for visiting fellowship. Authors thank Dr. D. Gunasekar, Professor, Sri Venkateswara University, India for suggesting the plant. The authors thank to Dr. S. Karuppusamy, Department of Botany, Madura College, Madurai for identification of plant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript, read and approved the final Manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanian, R., Subbramaniyan, P. & Raj, V. Antioxidant activity of the stem bark of Shorea roxburghii and its silver reducing power. SpringerPlus 2, 28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-28