Abstract

Background

In recent years inhibitors directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have evolved as effective targeting cancer drugs. Characteristic papulopustular exanthemas, often described as acneiform rashes, are the most frequent adverse effect associated with this class of novel cancer drugs and develop in > 90% of patients. Notably, the rash may significantly compromise the patients' quality of life, thereby potentially leading to incompliance as well as dose reduction or even termination of the anti-EGFR therapy. Yet, an effective dermatologic management of cutaneous adverse effects can be achieved. Whereas various case reports, case series or expert opinions on the management of EGFR-inhibitor (EGFRI) induced rashes have been published, data on systematic management studies are sparse.

Methods

Here, we present a retrospective, uncontrolled, comparative study in 49 patients on three established regimens for the management of EGFRI-associated rashes.

Results

Strikingly, patients' rash severity improved significantly over three weeks of treatment with topical mometason furoate cream, topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream, as well as topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream plus systemic isotretinoin.

Conclusions

In summary our results demonstrate that EGFRI-associated rashes can be effectively managed by specific dermatologic interventions. Whereas mild to moderate rashes should be treated with basic measures in combination with topical glucocorticosteroids or combined regiments using glucocorticosteroids and antiseptics/antibiotics, more severe or therapy-resistant rashes are likely to respond with the addition of systemic retinoids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent years inhibitors directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have evolved as effective cancer-targeting drugs [1]. These drugs include monoclonal anti-EGFR antibodies, such as cetuximab or panitumumab, as well as small molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as erlotinib or gefitinib. Additionally, current studies report promising results on the clinical effectiveness of drugs that target the EGFR-signaling cascade, such as the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib or MEK inhibitors [2]. Characteristic inflammatory papulopustular exanthemas, often described as acneiform or rosaceaform rashes, are the most frequent adverse effect associated with the use of EGFR-inhibtors (EGFRI) [3–6]. Within the first days to weeks of therapy > 90% of patients develop these rashes. In the majority of cases skin lesions initially appear within areas of skin that bear high densities of seborrheic glands. However, the rash may progress into other areas, generalize in the course, or progress into perifollicular xanthoma [7]. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated that rash appearance and severity are correlated positively with the anti-tumor effect of the EGFRI [8, 9]. Accordingly, the rash is regarded the best surrogate marker for clinical response to EGFR-targeting drugs [9]. Besides the rash, patients may develop additional dermatologic adverse effects, including pruritus, paronychias, infections, or impressive alterations of eyebrows and lashes [5, 6, 10–16]. Another notable aspect of EGFRI-associated cutaneous adverse effects is the severe radiation dermatitis following additional radiation therapy [17–20]. However, radio therapy prior to initiation of EGFRI therapy may also prevent rash development [21].

Taking into account the broad spectrum and the potential severity of EGFRI-associated adverse effects, it is reasonable that these toxicities may significantly compromise the patients' quality of life (QoL), thereby potentially leading to incompliance as well as dose reduction or even termination of the anti-EGFR therapy. Hence, effective management regimens are urgently needed.

Here, we report the results of a retrospective study designed to compare the effectiveness of established rash management strategies in EGFRI-associated rash development.

In our study patients were treated using one of three rash-management strategies: (1) sole topical anti-inflammatory measures (mometason furoate cream); (2) combined topical anti-inflammatory (prednicarbate cream) and anti-infectious measures (nadifloxacin cream); and (3) combined topical anti-inflammatory (prednicarbate cream), anti-infectious measures (nadifloxacin cream) as well as concomitant systemic isotretinoin therapy. All have previously been reported to be effective by several independent case reports and guidelines [5, 10, 22–25]. After three weeks of treatment, patient rashes were re-assessed to determine the effectiveness of each strategy.

Methods

Assessment of rash severity

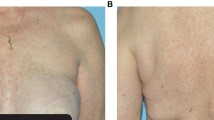

Rash severity was assessed during the initial presentation to our clinics (Departments of Dermatology, University Hospital Düsseldorf and Ludwig-Maximilian-University of Munich) and after three weeks of specific dermatologic therapy. Rash severity was assessed applying the EGFRI-induced rash severity score (ERSS or WoMoScore), a skin-specific scoring system introduced in 2008 [26]. Briefly, the ERSS is a combined score of the severity of five different aspects of the EGFRI-rash (color of erythema, distribution of erythema, papulation, pustulation and scaling/crusts), combined with a score based on the extent of affected facial area and the total body area involved. ERSSs range from 0 (no skin affection), 1 to 20 (mild), between 20 and 40 (moderate), up to scores exceeding 40 points, indicating severe cases (Figure 1) [26].

Patient selection criteria

Selection criteria included patients treated with cetuximab or erlotinib that suffered from EGFRI-associated rash at the time of referral. The selection was limited to initial patients and their follow-up visits in the time frame of March 2007 to October 2009. We enrolled 49 patients who presented with an ERSS of 10 or higher. The study was approved by the local ethics committees.

Treatment

In stage 1 of the study, 21 patients (ERSS 10.3 to 77.9) were treated topically with mometason furoate cream twice daily for three weeks. In stage 2 of the study, 23 patients (ERSS 12.5 to 67.1) were treated topically with nadifloxacin 1% cream once daily in the morning in combination with prednicarbate 0.25% cream once daily in the evening for three weeks as described [22, 27]. In stage 3 of the study, five patients with an ERSS > 50 received topical nadifloxacin 1% and prednicarbate 0.25% cream in combination with the systemic retinoid isotretinoin 10 to 20 mg/d for three weeks as described [25]. Adverse effects of our management strategies were generally rare and in line with the potential common adverse effects reported for each drug in the literature.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test.

Results

In this study we sought to compare the effectiveness of established rash management strategies. Therefore, we first assessed the efficacy of a potent anti-inflammatory topical glucocorticosteroid with low-atrophogenic potential [28]. Twenty-one patients (ERSS ranging from 10.3 to 77.9) were treated with mometason furoate cream. Assessment of the ERSS prior to therapy initiation and after three weeks revealed that the mean rash severity improved significantly (P = 0.00009) from 45.9 to 27.0 and demonstrated the efficacy of our approach (Figure 2A).

Significant improvement of rash severity under specific dermatologic measures. (A) Topical mometason furoate cream significantly (P = 0.0009) improved the severity of the skin rash (ERSS) in patients treated with EGFRI after three weeks. (B) A combined topical regimen with prednicarbate cream and nadifloxacin cream significantly (P = 0.03) improved the ERSS in patients treated with EGFRI after three weeks. (C) A triple therapy with topical prednicarbate cream, topical nadifloxacin cream and systemic isotretinoin significantly (P = 0.015) improved the ERSS in patients treated with EGFRI after three weeks. Statistical analyses were performed applying the Student's t-test.

The second regimen used, a combined approach, which targets the inflammatory as well as the infectious facet of the rash. Twenty-three patients (ERSS ranging from 12.5 to 67.1) were treated with nadifloxacin 1% cream, a potent topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic with a broad-spectrum activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as the topical glucocorticosteroid prednicarbate 0.25% cream as described previously [24]. Assessment of the ERSS revealed that the mean rash severity improved significantly (P = 0.03) from 30.9 to 24.8 after three weeks, demonstrating the efficacy of our approach (Figure 2B).

Finally, we included the retinoid isotretinoin that represents a standard option for the treatment of papulo-pustular skin diseases like acne or rosacea [4, 29]. Moreover, isotretinoin has been reported to be effective in the management EGFR-antagonist rashes [5, 25]. Five patients, which presented with severe ERSS of > 50 or therapy-resistant courses were treated with nadifloxacin 1% cream, prednicarbate 0.25% cream, and systemic isotretinoin (10 to 20 mg/day) [5, 25]. Interestingly, these severely affected patients significantly improved during isotretinoin treatment (P = 0.015) and demonstrated on average a reduction of the ERSS from 59.2 to 43.8 after three weeks of therapy (Figure 2C).

All results are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

Today, there is a broad variety of independent case reports and guidelines on different options for the management of EGFRI-associated rashes [5, 22–25]. Yet, studies that compare different therapeutic regimens and analyses in larger collectives of patients are sparse. Accordingly, we conducted a comparative analysis of the clinical efficacy of different EGFRI rash management strategies that target the inflammatory and/or the infectious characteristics of the rash. Notably, our results demonstrate that all approaches were effective and significantly reduced the severity of the rash over a period of three weeks.

The statistically most significant effects were achieved with topical mometason furoate cream (P = 0.00009), followed by topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream plus systemic isotretinoin (P = 0.015) and finally topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream (P = 0.03). However, statistical comparison of different therapy regimen is limited due to variations in patient numbers and rash severity in each of the three test groups before therapy. Topical mometason furoate achieved the highest mean ERSS-reduction with 18.9 points, followed by topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream plus systemic isotretinoin with 15.4 points and topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream with 6.1 points. Moreover, topical mometason furoate was the only therapy that resulted in a complete resolution of all rash symptoms in one patient. Yet, it must be noted that statistical significance is highly dependent on the number of patients included in each group, and because the ERSS system was designed with a non-linear affected-area scale emphasizing minor variations in mild patients with face involvement only [26].

Mometason furoate alone appeared to be more effective than prednicarbate plus topical nadifloxacin. However, mometason furoate is the more potent glucocorticosteroid (class III) as compared to prednicarbate (class II) and therefore represents a higher risk of inducing steroid-associated adverse effects, such as skin atrophy [30]. Nevertheless, it is questionable, whether these adverse effects may play a role in the short-term treatment of EGFRI rashes, as inflammatory skin lesions have been shown to slowly regress even without therapy in the course of sustained EGFRI-therapy. Topical nadifloxacin was administered to target the infectious component of the rash [10]. Future studies may analyse the efficacy of a combination of topical momentason furoate plus nadifloxacin.

With regard to the variation in significance and over-all efficacy of the different approaches, it must be noted that we compared three somewhat heterogenous patient groups. Whereas patients with varying ERSS were randomly subjected to therapies with topical mometason furoate or topical prednicarbate cream plus nadifloxacin cream, the addition of systemic isotretinoin was limited to patients that were severely affected and presented either with a very high ERSS (> 50) or patients that were referred to our clinics due to rashes that were therapy-resistant to other approaches (such as topical antibiotics or topical glucocorticosteroids). Accordingly, effects observed for systemic isotretinoin may not have been as dramatic when compared to sole topical prednicarbate plus topical nadifloxacin or topical mometason furoate.

With regard to study design, it may be criticized that we did not compare the tested conditions to negative controls, such as a subgroup of EGFRI patients whose rash was left untreated for the study period. Yet, an untreated or insufficiently managed rash can significantly compromise the patients' QoL and patients included in our analysis had initially been referred to us specifically for the treatment of their cutaneous adverse effects by their treating oncologists.

Notably, all approaches that were analysed in this study are in line with recent expert recommendations that suggest an escalating strategy for the management of the EGFRI rash [5, 6, 16] with a succession of treatments, as indicated, summarized as follows: intensive skin care in combination with mild cleansers, followed by the use of mild (class II) to moderate (class III) potent topical glucocorticosteroids with low atrophogenic potential such as hydrocortisone butyrate, prednicarbate (both class II), methylprednisolone aceponate or momethason furoate (both class III). In fact, our results demonstrate a significant efficacy of topical glucocorticosteroid monotherapy. Taking into account the high incidence of bacterial superinfections of the EGFRI rash, alternative recommendations include the combination of mild topical glucocorticosteroids and topical antibiotics or antiseptics with low cytotoxic potential [31]. Recent studies report infections at the sites of dermatologic adverse effects in 38% of EGFRI rash patients. A detailed microbiologic analysis of these cutaneous infections identified Staphylococcus aureus in 59.5% of the cases [10, 32]. Nadifloxacin is a potent topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic hence representing a probable candidate to target superinfections in EGFRI rash patients. In fact, we could show that the combination of nadifloxacin 1% cream and prednicarbate 0.25% cream significantly improved rash severity. In this context the management of cutaneous infections is also likely to exert protective effects regarding the aggravation of skin inflammation as infectious agents may trigger inflammatory rash progression by means of "Koebnerization" [33]. Systemic isotretinoin, finally, is recommended for the management of severe EGFRI rashes of rashes that do not respond to other therapies [23]. Hence, in our study, patients with an ERSS > 50 were subjected to a combined management approach with nadifloxacin 1% cream and prednicarbate 0.25% cream as well as systemic isotretinoin [25]. Our results demonstrate that even severe rashes can be improved significantly by this approach. Yet, is must be noted that the use of systemic isotretinoin in EGFRI patients is controversial, since potential antagonism of the anti-tumor effect of the EGFRI is possible, although this has not been investigated systematically yet. Nevertheless, similar arguments may be proposed for any systemic approach, such as the administration of oral tetracyclines as rash prophylaxis [34, 35].

Conclusions

In summary our results demonstrate that EGFRI-associated rashes can be effectively managed by specific dermatologic interventions. Whereas mild to moderate rashes should be treated with basic measures in combination with topical glucocorticosteroids or combined regiments using glucocorticosteroids and antiseptics/antibiotics, more severe or therapy-resistant rashes are likely to respond with the addition of systemic retinoids. Additional options include systemic antibiotics or systemic glucocorticosteroids. Finally, novel approaches have been proposed to abrogate EGFR-inhibition specifically in the skin. One such option is the ligand-independent activation of the EGFR by topical application of vitamin K analogues, such as vitamin K1 or vitamin K3 (menadione) [36–39]. Yet, additional systematic studies are urgently needed to quantify and compare the effectiveness and adverse effects of EGFRI rash-management strategies.

References

Ciardiello F, Tortora G: EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med 2008, 358: 1160–1174. 10.1056/NEJMra0707704

Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M, Hogg D, Lorigan P, Lebbe C, Jouary T, Schadendorf D, Ribas A, O'Day SJ, Sosman JA, Kirkwood JM, Eggermont AM, Dreno B, Nolop K, Li J, Nelson B, Hou J, Lee RJ, Flaherty KT, McArthur GA: Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011, 364: 2507–2516. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782

Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Kurle S, Homey B: [Therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clinical spectrum of cutaneous adverse effects]. Hautarzt 2010, 61: 654–661. 10.1007/s00105-010-1943-6

Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, Homey B: Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2011, 15: 40–47. 10.1038/jidsymp.2011.9

Gutzmer R, Becker JC, Enk A, Garbe C, Hauschild A, Leverkus M, Reimer G, Treudler R, Tsianakas A, Ulrich C, Wollenberg A, Homey B: Management of cutaneous side effects of EGFR inhibitors: recommendations from a German expert panel for the primary treating physician. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011, 9: 195–203.

Potthoff K, Hofheinz R, Hassel JC, Volkenandt M, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, Karthaus M, Riess H, Lipp HP, Hauschild A, Trarbach T, Wollenberg A: Interdisciplinary management of EGFR-inhibitor-induced skin reactions: a German expert opinion. Ann Oncol 2011, 22: 524–535. 10.1093/annonc/mdq387

Eames T, Kroth J, Flaig MJ, Ruzicka T, Wollenberg A: Perifollicular xanthomas associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 2010, 90: 202–203. 10.2340/00015555-0792

Perez-Soler R, Chachoua A, Hammond LA, Rowinsky EK, Huberman M, Karp D, Rigas J, Clark GM, Santabarbara P, Bonomi P: Determinants of tumor response and survival with erlotinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004, 22: 3238–3247. 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.057

Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, Witt K, Clark G, Cagnoni PJ: Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13: 3913–3921. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2610

Eilers RE Jr, Gandhi M, Patel JD, Mulcahy MF, Agulnik M, Hensing T, Lacouture ME: Dermatologic infections in cancer patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010, 102: 47–53. 10.1093/jnci/djp439

Forton F, Seys B: Density of Demodex folliculorum in rosacea: a case-control study using standardized skin-surface biopsy. Br J Dermatol 1993, 128: 650–659. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00261.x

Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Cevikbas F, Bolke E, Steinhoff M, Homey B: Preliminary evidence for a role of mast cells in epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010, 63: 163–165. 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.023

Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Homey B: More on aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med 2011, 364: 486–487.

Gerber PA, Homey B: Images in clinical medicine. Erlotinib-induced hair alterations. N Engl J Med 2008, 358: 1175. 10.1056/NEJMicm073144

Shah NT, Kris MG, Pao W, Tyson LB, Pizzo BM, Heinemann MH, Ben-Porat L, Sachs DL, Heelan RT, Miller VA: Practical management of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23: 165–174.

Wollenberg A, Kroth J, Hauschild A, Dirschka T: Cutaneous side effects of EGFR inhibitors-appearance and management. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2010, 135: 149–154. 10.1055/s-0029-1244831

Bernier J, Russi EG, Homey B, Merlano MC, Mesia R, Peyrade F, Budach W: Management of radiation dermatitis in patients receiving cetuximab and radiotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: proposals for a revised grading system and consensus management guidelines. Ann Oncol 2011, 22: 2191–2200. 10.1093/annonc/mdr139

Bolke E, Gerber PA, Lammering G, Peiper M, Muller-Homey A, Pape H, Giro C, Matuschek C, Bruch-Gerharz D, Hoffmann TK, Gripp S, Homey B, Budach W: Development and management of severe cutaneous side effects in head-and-neck cancer patients during concurrent radiotherapy and cetuximab. Strahlenther Onkol 2008, 184: 105–110. 10.1007/s00066-008-1829-z

Budach W, Bolke E, Homey B: Severe cutaneous reaction during radiation therapy with concurrent cetuximab. N Engl J Med 2007, 357: 514–515. 10.1056/NEJMc071075

Sartor CI: Mechanisms of disease: Radiosensitization by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2004, 1: 80–87.

Gerber PA, Enderlein E, Homey B, Muller A, Boelke E, Budach W: Radiation-induced prevention of erlotinib-induced skin rash is transient: a new aspect toward the understanding of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor associated cutaneous adverse effects. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25: 4697–4698. author reply 4698–4699 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8330

Bernier J, Bonner J, Vermorken JB, Bensadoun RJ, Dummer R, Giralt J, Kornek G, Hartley A, Mesia R, Robert C, Segaert S, Ang KK: Consensus guidelines for the management of radiation dermatitis and coexisting acne-like rash in patients receiving radiotherapy plus EGFR inhibitors for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol 2008, 19: 142–149.

Gutzmer R, Werfel T, Mao R, Kapp A, Elsner J: Successful treatment with oral isotretinoin of acneiform skin lesions associated with cetuximab therapy. Br J Dermatol 2005, 153: 849–851. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06835.x

Katzer K, Tietze J, Klein E, Heinemann V, Ruzicka T, Wollenberg A: Topical therapy with nadifloxacin cream and prednicarbate cream improves acneiform eruptions caused by the EGFR-inhibitor cetuximab - A report of 29 patients. Eur J Dermatol 2010, 20: 82–84.

Wollenberg A, Moosmann N, Kroth J, Heinemann V, Klein E: Therapy of severe cetuximab-induced acneiform eruptions with oral retinoid, topical antibiotic and topical corticosteroid. Hautarzt 2007, 58: 615–618. 10.1007/s00105-006-1256-y

Wollenberg A, Moosmann N, Klein E, Katzer K: A tool for scoring of acneiform skin eruptions induced by EGF receptor inhibition. Exp Dermatol 2008, 17: 790–792. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00715.x

Tokumaru S, Sayama K, Shirakata Y, Komatsuzawa H, Ouhara K, Hanakawa Y, Yahata Y, Dai X, Tohyama M, Nagai H, Yang L, Higashiyama S, Yoshimura A, Sugai M, Hashimoto K: Induction of keratinocyte migration via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. J Immunol 2005, 175: 4662–4668.

Prakash A, Benfield P: Topical mometasone. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in the treatment of dermatological disorders. Drugs 1998, 55: 145–163. 10.2165/00003495-199855010-00009

Powell FC: Clinical practice. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2005, 352: 793–803. 10.1056/NEJMcp042829

Schoepe S, Schacke H, May E, Asadullah K: Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol 2006, 15: 406–420. 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00435.x

Marquardt C, Matuschek E, Bolke E, Gerber PA, Peiper M, J VS-K, Buhren BA, van Griensven M, Budach W, Hassan M, Kukova G, Mota R, Hofer D, Orth K, Fleischmann W: Evaluation of the tissue toxicity of antiseptics by the hen's egg test on the chorioallantoic membrane (HETCAM). Eur J Med Res 2010, 15: 204–209. 10.1186/2047-783X-15-5-204

Kujath P, Kujath C: Complicated skin, skin structure and soft tissue infections - are we threatened by multi-resistant pathogens? Eur J Med Res 2010, 15: 544–553.

Gerber PA, Enderlein E, Homey B: The Koebner-phenomenon in epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced cutaneous adverse effects. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26: 2790–2792. 10.1200/JCO.2007.16.0077

Scope A, Agero AL, Dusza SW, Myskowski PL, Lieb JA, Saltz L, Kemeny NE, Halpern AC: Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25: 5390–5396. 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6987

Wilke MH: Multiresistant bacteria and current therapy - the economical side of the story. Eur J Med Res 2010, 15: 571–576. 10.1186/2047-783X-15-12-571

Abdelmohsen K, Gerber PA, von Montfort C, Sies H, Klotz LO: Epidermal growth factor receptor is a common mediator of quinone-induced signaling leading to phosphorylation of connexin-43: role of glutathione and tyrosine phosphatases. J Biol Chem 2003, 278: 38360–38367. 10.1074/jbc.M306785200

Abdelmohsen K, von Montfort C, Stuhlmann D, Gerber PA, Decking UK, Sies H, Klotz LO: Doxorubicin induces EGF receptor-dependent downregulation of gap junctional intercellular communication in rat liver epithelial cells. Biol Chem 2005, 386: 217–223. 10.1515/BC.2005.027

Klotz LO, Patak P, Ale-Agha N, Buchczyk DP, Abdelmohsen K, Gerber PA, von Montfort C, Sies H: 2-Methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone, vitamin K(3), decreases gap-junctional intercellular communication via activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor/extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade. Cancer Res 2002, 62: 4922–4928.

Li T, Perez-Soler R: Skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Target Oncol 2009, 4: 107–119. 10.1007/s11523-009-0114-0

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Hevezi (University of California, Irvine, CA, USA) for editing the manuscript for language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PAG, SM, and BH participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. PAG, BH, EB, SM, TE, BAB, HS, SH, LME, AW, CM and WB helped to design and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Peter Arne Gerber, Stephan Meller, Andreas Wollenberg and Bernhard Homey contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gerber, P.A., Meller, S., Eames, T. et al. Management of EGFR-inhibitor associated rash: a retrospective study in 49 patients. Eur J Med Res 17, 4 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783X-17-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783X-17-4