Abstract

Background

Predicted increases in stream temperature due to climate change will have a number of direct and indirect impacts on stream biota. A potential intervention for mitigating stream temperature rise is the use of wooded riparian zones to increase shade and reduce direct warming through solar radiation. To assess the effectiveness of this intervention, we conducted a systematic review of the available evidence for the effects of wooded riparian zones on stream temperature.

Methods

We searched literature databases and conducted relevant web searches. Inclusion criteria were: subject - any stream in a temperate climate; intervention - presence of trees in the riparian zone; comparator - absence of trees in the riparian zone; outcome measure - stream temperature. Included studies were sorted into 3 groups based on the scale of the intervention and design of the study. Two groups were taken forward for synthesis; Group 1 studies comparing water temperature in streams with and without buffer strips/riparian cover and Group 2 comparisons of stream temperatures in open and forested landscapes. Temperature data were extracted and quantitative synthesis performed using a random effects meta-analysis on the differences in mean and maximum temperature.

Results

Ten studies were included in each of Groups 1 and 2. Results for both groups suggest that riparian wooded zones lower spring and summer stream temperatures. Lowering of maximum is greater than lowering of mean temperature. Further analysis of environmental variables that might modify the effects of the intervention was not possible using the limited set of studies.

Conclusions

Wooded riparian zones can reduce stream temperatures, particularly in terms of maximum temperatures. Because temperature is known to affect fish, amphibian and invertebrate life history, the reported effect sizes are likely to have a biological significance for the stream biotic community. Consequently investment in creation of wooded riparian zones might provide benefits in terms of mitigating some of the ecological effects of climate change on water temperature. Considerable uncertainty lies in the environmental variables that may modify the cooling effect of wooded riparian zones, and therefore it is not possible to identify when the use of this intervention for cooling would be most valuable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that stream water temperature may be increasing [1], which may have direct effects on poikilothermic organisms. There has been a particular concern that extreme summer temperatures due to climate change will affect fish populations. For instance, temperature can affect fish behaviour such as migration, leading to changes in the distribution and structure of river communities [2, 3]. Temperature can also affect metabolism and feeding, changing growth rate and important life history traits such as fecundity and longevity [4, 5] and disease susceptibility [6]. Similar concerns regarding the effects of increasing temperatures can be made for amphibians [7] and invertebrates [8]. Additionally, changes in riparian temperature can have a diverse range of impacts on primary productivity and decomposition, and may lead to changes in the structure and functioning of the whole biotic community [8, 9]. Although, the relative importance of water temperature, compared to other environmental factors that may also be changing, can be difficult to isolate e.g. [4]. Notably, riparian habitat can affect the amount of solar (shortwave) radiation received by the stream (i.e. the dominant heat flux) and so removal of tree cover may lead to an increase in water temperature [10]. In addition to energy receipt, other factors including hydraulic retention time and hydrological fluxes, especially ground water inflow or outflow, may also affect stream temperature [11–14], and affect the importance of riparian habitat for water temperature.

The riparian zone is the transition zone between a freshwater and terrestrial ecosystem [15]. The unique, dynamic and complex nature of riparian habitat means that it can support relatively high biodiversity and hence can be important for conservation management [9]. Changes in land use and river regulation may have led to a reduction in wooded riparian habitats next to rivers and streams; evidence is largely anecdotal but in many heavily grazed areas there is clearly little natural regeneration of trees to replace any lost through windthrow or bank erosion. Different activities have contributed to the declining riparian woodland, such as logging for timber [16] and livestock grazing and trampling [17]. Increasingly, there is concern that degradation of this habitat, and loss of riparian trees, may lead to a reduction in the abundance and diversity of species in the aquatic environment [9].

The riparian zone can play a key role in the functioning of the aquatic ecosystem, affecting chemical, physical and biological processes [9, 15]. Therefore, degradation of this environment has implications for many different aspects of river function and services, such as a loss of bank stability leading to increased erosion and chemical leaching from the surrounding land. One potentially major impact of riparian habitat on stream functioning is via its influence on water temperature [10, 18].

Management interventions have been proposed to limit the consequences of riparian degradation, such as the use of riparian buffer strips [19, 20] or livestock exclusion fencing [17]. Empirical research has been carried out to explore the importance of the riparian habitat and several reviews have been published addressing issues on this topic such as the effects of logging [16] and livestock [17] on stream and riparian ecosystems, and the relationship between stream temperature and forest harvesting [10].

Restoration of riparian trees has been proposed as a means of increasing shade and countering rising stream temperature in the context of unavoidable climate change [21]. However, the scientific basis for these management decisions is limited with respect to stream temperature due to a lack of understanding of key physical processes to inform predictive modelling of land use change [18].

This review examines the empirical evidence for the relationship between wooded riparian cover and stream temperature. CEE systematic review guidelines were used to comprehensively search for data, critically appraise the quality of study and quantitatively synthesise and compare the outcomes of different studies.

Methods

A review protocol was produced, which outlined the proposed plan of the systematic review [22].

Searches

Searching for relevant research data was conducted using a range of databases and document types (peer-reviewed, theses, grey literature) to ensure a comprehensive and, as much as possible, unbiased sample of the relevant literature was obtained. In each case, no time or document type restrictions were applied. The following databases were used: Agricola, CAB abstracts, Conservation evidence, Copac, Index to Thesis on-line, Science Direct, Web of Science. The following search terms (where * denotes a wild card term) were used to search the databases. ((stream* or river*) and (forest* or wood*) and (afforest* or harvest* or logg*) and (temperature*)) (riparian) AND temperature* AND (logg* OR harvest* OR tree* OR shad* OR wood* or forest*).

An internet search was undertaken using the following web sites: United States Forest Service, Unites States Fish and Wildlife Service, Environment Agency, Scottish Natural Heritage, European Environment Agency. World Wildlife Fund, Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Forest Research, River Restoration Centre, Freshwater Biological Association, Marine Scotland, Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Forest Commission, Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Countryside Council for Wales and the Tweed Foundation. We also used Google to perform a general internet search. Either all publication titles were scanned or search words, such as ‘riparian’and/or ‘water temperature’ used to search the site, depending on the search capability of the website and the number of publications.

Experts in the field, identified by review team members, were also contacted directly for suggestions of relevant studies.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

References captured from computerised databases were imported into an Endnote library and duplicates were removed. The following inclusion criteria were applied to each article: relevant subject(s) - any stream in a temperate climate; types of intervention - presence of trees in the riparian zone; types of comparator - absence of trees in the riparian zone; types of outcome measured - stream temperature.

In the first instance, the inclusion criteria were applied to title only to efficiently remove clearly irrelevant citations. Articles remaining were filtered further by viewing abstracts and then full text, to reach the final list of relevant articles. Two reviewers repeated the application of inclusion criteria on a subset (205 papers) at title and abstract reading level to ensure repeatability, calculated a kappa statistic of 0.54 and any discrepancies were resolved. After Kappa, the rules for title and abstract inclusion were clarified between the reviewers (exclusion of studies that only mention lakes, tropical climates, channelization/restoration/grazing/fires/hurricanes, unless it clearly created differences in riparian tree cover, or no indication of water temperature measurement in the abstract).

Studies that met the inclusion criteria of the review were pooled into three groups:

-

1)

Studies comparing water temperature in reaches/streams with buffer strips versus reaches/streams without buffer strips. Usually this comparison was created following logging (i.e. the comparison was streams that were fully logged versus streams which were logged but a buffer strip was left) but there a study [23] that involved the deliberate planting of buffer strips in comparison to a site without planting and a study that focused only on the effect of open/shaded riparian cover [24].

-

2)

Studies comparing water temperature in reaches/streams through meadows/moorland versus forests/plantations.

-

3)

Studies aiming to investigate the effects of forest harvesting and therefore comparing water temperature in logged versus unlogged (i.e. undisturbed) reaches or catchments.

Study quality assessment

Basic information was extracted from articles (from groups 1 and 2), when available, which included details of location of study (country and catchment/ river name), type of forest (as described by the author), type of study (before and after, inter-site comparison), intervention type (logging, buffer following logging, planted, experimental [i.e. the change in tree density was a manipulation performed by the researcher] etc.), number of catchments/streams, pairing of sites, presence of confounders/other managements, times of data collection and the presentation of data that would be suitable for meta-analysis. For group 3, information has also been recorded, when available, on buffer width and length, aspect of sites, stream width, elevation, stream discharge, habitat (e.g. pool-riffle) and stream order.

Data extraction strategy

Temperature data were extracted from articles or obtained from the author. In most cases, the observed temperature measurements could be extracted; exceptions were two studies presenting temperature change between upstream and downstream [25, 26] or one study presenting temperatures change from a forest control [27]. Effect sizes from studies were calculated as the difference between average temperature in the streams with trees and average temperature in streams without trees in the riparian zone (or difference in the temperature change in the case of the three studies cites above). We used a non-standardised metric as all studies measured temperature in the same units (degrees Celsius =°C). The variance of the effect size was calculated as the standard error of the difference between the means. Standard error for each mean was extracted when possible from the article (if multiple variances were presented, their average, and then the standard error was calculated) or calculated using temperature data presented; sample size was the number of reaches in each group. In the case of buffer studies, if there was more than one buffer width in a study, effect sizes were calculated separately for each width. Effect sizes of the average difference in maximum temperature are based on either average daily maximum or maximum observed over the study period depending on how the data were presented (in some studies this was not clearly reported). To separate effect sizes by seasons, we followed the classification of spring and summer of the author; in cases when this was not stated, we labelled spring as March -May, and summer as June-August (all included studies collected data in the Northern Hemisphere). Spring and summer were considered as the focus of the review was on higher temperatures due to their potentially lethal effects on biota. For the same reason, minimum temperature was not considered as a measure of thermal response to riparian land cover.

Data synthesis and presentation

For groups 1 and 2 Six analyses have been run for each group of studies: (1) averages based on any/all data available (2) maximums based on any/all data available; (3) as 1 except for spring data only; (4) as 2 except for spring data only; (5) as 1 except for summer data only; (6) as 2 except for summer data only. Data from Group 3 were not extracted/analysed (see section 4.4).

The basic analysis (1) was a random effects meta-analysis with weighting by inverse variance to calculate the average effect size and its 95% confidence interval. We ran a series of analyses to verify the robustness of these results. (2) An unweighted analysis with the same total error as the weighted analysis; this was to test whether the assumption of comparability of the variance calculation of different studies was important. (3) Analysis 1 repeated on the aggregated data set (i.e. averaging over multiple data points from the same article) to account for issues of non-independence. We also performed (4) a test for the presence of publication bias [28], as indicated by a relationship between the effect size and precision (inverse variance of effect size), using the on the aggregated data set when there was at least four articles in the analysis. Using Stata’s “Metainf” function (5), we tested the effect of removing each effect size, one-by-one in turn, on the average effect obtained by the meta-analysis of analysis 1 to verify that the results from single studies were not driving the overall average results. Finally (6), for studies in Group 1, we tested the relationship between buffer width and effect size with metaregression, which can be regarded as the same as standard regression (investigating whether the slope of the relationship significantly differs from zero) but individuals points (i.e. effect sizes) are weighted by their inverse variance, following the standard procedure of meta-analysis.

Results

Review statistics

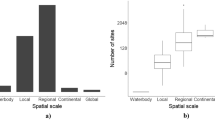

An initial search was conducted on 22nd December 2008. The search was updated on the 5th August 2010 using the main databases from the first search. The initial search found a total of 1042 articles and the updated search found an additional 137 articles (including 4 articles suggested by experts, 3 which had only been published online and so had not yet been added to databases and one which was not picked up by the search terms) (see Additional file 1 for details of search results). Of those articles captured in the initial search, 293 articles passed title and abstract inclusion, of which 204 were successfully retrieved and read at full text. Of the articles captured in the updated search 24 passed the title and abstract inclusion. Following full text assessment, and assessment of articles from which data could be extracted, 39 articles were initially included in the review. The updated search found three additional articles.

Group 1

Group 1 included studies comparing water temperature in streams with and without buffer strips/riparian cover. Ten articles were identified following full text assessment, and from which data could be retrieved [23–27, 29–33]. These studies were conducted in USA (4), Canada (3), New Zealand (2) and UK (1). Eight were site comparison studies while the remaining two also had before-after data (BACI design). The interventions were: buffers created following harvesting (5 studies; in 2 cases the buffer was experimentally removed [i.e. the manipulation was performed by the researcher] for comparison); experimental buffer manipulations (3); planted buffer schemes (1) and a comparison of ‘open’ versus ‘shaded’ riparian zones (1). See Additional file 2 for further details on these studies.

Analysis was conducted on the differences in average and maximum temperature. Firstly, data from all months were analysed together to maximise the number of studies in each analysis. Secondly, spring and summer months were analysed separately. See Additional file 3 for the forest plots of each analysis.

The overall mean difference in mean temperature of streams with and without a buffer strip was 0.39°C (95% CI = -0.13, 0.91). The effect size is larger for maximum temperature than mean temperatures (Table 1). Maximum temperature was 3.16°C lower in the presence of buffer strips (95% CI = 2.06, 4.27). There was no evidence that the effect varied among different studies (no significant heterogeneity) in the weighted analysis. However, there was some evidence of variation in the summer mean and maximum differences among the results of different studies in the unweighted analysis. This was probably because the studies reporting the largest effect sizes were downweighted in the weighted analysis because of their greater variance.

The pattern in temperature difference is reflected in the spring and summer means and maxima. Small sample sizes restrict further analysis but average differences in maximum temperature in the order of 2–3°C are typical for both seasons. The outcomes appear reasonably robust to whether studies are weighted by inverse of variance, and the results were not driven by data from single studies.

Metaregression found no significant effect of buffer width but the statistical power was low because of the low number of studies. In all analyses, the coefficient was positive, which indicates that the difference in temperature tended to increase with greater buffer widths.

Group 2

Group 2 included studies comparing streams temperatures in open and forested landscapes. Ten studies were identified following full text assessment, and from which data could be retrieved (see Additional file 4) [34–43]. These studies were in: New Zealand (3), UK (2), USA (2), Ireland (1), Spain (1) and Denmark (1). All were site comparisons. See Additional file 5 for the forest plots of each analysis.

The overall mean difference in mean temperature of open-landscape and forested streams is 1.48°C (95% CI = 0.60, 2.36). The effect size is larger for maximum temperature than mean temperatures (Table 2). Maximum temperature was 4.94°C, lower in the presence of forest (95% CI = 2.70, 7.17). However, there is evidence that the effect varied among different studies (significant heterogeneity). Compared with Group 1 the effects sizes for mean and maximum temperature were markedly larger.

As with Group 1, the patterns in the seasonal means and maxima are similar to those of the annual values. Small samples sizes restrict further analysis. Unweighted figures suggests the weighting of effect sizes (by inverse variance) did not fundamentally alter the outcome of the synthesis, which suggests these results are robust to the assumption of comparability of variance calculation from different studies made by the meta-analysis. However, there was some evidence that single studies modified the magnitude of the effect size, increasing or decreasing it, but even so the general interpretation of the average was not affected.

Group 3

Group 3 included studies investigating the effects of forest harvesting and therefore comparing water temperature in logged versus unlogged (i.e. undisturbed) reaches or catchments. This group of studies has more complexity because in many cases, although trees were logged from the riparian zone, this did not necessary lead to a decrease in riparian shade because the logged trees were not always retrieved when they fell across the stream. Some studies reported that trees/woody logging debris was removed while others did not report this issue at all. Because of this problem, investigation of group 3 data would be better conducted as a separate review on the effects of logging rather than included in our review, which is considering the effects of riparian shade. Group 3 is primarily composed of North American/Canadian studies of the effects of logging old growth forests. A list of included articles is provided in Additional file 6.

Discussion

Data from the included studies were broadly in agreement that streams with trees in the riparian zone have a lower average water temperature, and reach lower maximum temperatures, than streams without trees in the riparian zone. The confidence intervals indicate the uncertainty in the magnitude of these effects.

Despite the consistency in the pattern, the strength of evidence this provides depends on the methodological quality of the studies in the analysis. Most of these studies were site comparisons (i.e. they compared the water temperature among streams, or different sections of the same stream, under different wooded riparian zone treatments). Significantly, many did not have baseline data to verify that the stream temperatures were similar in the absence of differences in tree presence. Further experimental manipulation e.g. [31] of tree presence could provide more reliable estimates of the effect size by accounting for the effects of confounding variables.

\Our study was able to estimate the average effect size of the temperature difference across different studies. However, ideally, within a meta-analysis, variation in effect size among studies would be explored. We investigated the effect of buffer width. No significant effect was found but a larger sample size would improve statistical power. In particular, there was evidence of heterogeneity within the comparison of open and forested landscapes. Information on variables, such as river discharge, stream order, habitat type, aspects and other variables that may affect temperature were reported to varying extents by the articles. Because of this variation in reporting, in combination with the low number of studies, we could not explore the role of these variables on the effect size. Similarly, variation in how water temperature data were reported in the articles, which meant that the same data calculation procedure could not be applied consistently to all studies, could have affected our meta-analysis. However, the general similarity between the patterns of the weighted meta-analysis and unweighted averages indicate this did not introduce serious bias. Standardization of water temperature data presentation, and environmental contextual variables, as listed above, would aid future meta-analysis. We suggest that climate will be a first order driver but basin properties affecting microclimate and hydrology (relative contribution from surface vs. groundwater) and scaling (to thermal capacity) will also be important.

Most of the included studies measured water temperature from a small number of separate reaches. This is perhaps not surprising given the extensive fieldwork that can be involved. However, this feature does mean that it is not possible to make general conclusions based on the findings of a single study. Therefore, the approach of meta-analysis, combining data from multiple studies, is particularly powerful in this area of research to make more general conclusions on the effects of interventions. Meta-analysis can also be a simpler approach to ask questions such as on the effect of climate types that would be difficult to address within a single study, which are usually focused on one geographic region. However, meta-analysis is still limited by the number of studies reporting data that can be extracted.

Conclusions

Implication for policy

This systematic review provides evidence that wooded riparian zones can reduce stream temperatures, particularly in terms of maximum temperatures. Additionally, since temperature is known to affect fish and invertebrate life history, the reported effect sizes are likely to have a biological significance for the stream biotic community. Consequently investment in creation of wooded riparian zones might provide benefits in terms of mitigating some of the ecological effects of climate change on water temperature. Considerable uncertainty lies in the environmental variables that may modify the cooling effect of wooded riparian zones, and therefore it is not possible to identify when the use of trees for cooling would be most valuable. Variables such as stream width and river discharge (thermal capacity), river basin location (headwater or lowlands) and the degree to which the wider catchment is forested are likely to be critical controls on the efficacy of riparian trees as a temperature moderator. Our analysis also does not inform on how trees should be planted, in terms of buffer width, length of reach requiring a buffer and the types of trees that should be planted, nor on the roles of stand density/age and nature of understory vegetation. The results were broadly similar between group 1 (local scale tree variation e.g. buffers) and group 2 (larger scale tree variation e.g. forest/plantation), at least based on the limited data set we obtained (confidence intervals for the weighted average overlap except for spring maximum); however, our analysis did not specially test for a difference between these two groups, and this clearly requires further investigation. More strategic allocation of resources to riparian intervention requires development of the evidence base on the influence of these variables. Additionally, as stream biota vary in their specific thermal requirements [5, 44, 45], and the impacts of climate change are not likely to be geographically uniform, the application of wooded buffer zones to reduce water temperature should be applied on a case by case basis to maximize their utility.

Implication for research

Using basic comparisons of stream temperature between treatment and control sites, it has been possible to demonstrate an effect of wooded riparian zones on both mean and maximum temperatures. The challenge for research is to enable better prediction of the effect of such an intervention across the full range of rivers and streams, as well as to provide information on the most effective design of riparian buffer.

Fundamental process understanding about the energy and hydrological fluxes that determine river temperature in different riparian zone contexts is required. This mechanistic understanding is needed to underpin transferrable, process-based modelling studies and to factor out/ in confounding factors other than riparian tree cover.

Future research would be facilitated by standardisation of study design and reporting standards, particularly regarding the selection of temperature sampling sites, the presentation of means and variances over time and space and the reporting of other key environmental variables that can be expected to modify the effect size of the presence of trees in the riparian zone.

Although research suggests a link between the fish and other biota and water temperature, given that wooded buffer may have effects other than those on water temperature, further work should aim to review the evidence for effects of wooded buffer zones on biotic communities.

References

Kaushal SS, Likens GE, Jaworski NA, Pace ML, Sides AM, Seekell D, Belt KT, Secor DH, Wingate RL: Rising stream and river temperatures in the United States. Front Ecol Environ 2010, 8: 461–466. 10.1890/090037

Daufresne M, Boet P: Climate change impacts on structure and diversity of fish communities in rivers. Glob Chang Biol 2007, 13: 2467–2478. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01449.x

Jonsson B, Jonsson N: A review of the likely effects of climate change on anadromous Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and brown trout Salmo trutta, with particular reference to water temperature and flow. J Fish Biol 2010, 75: 2381–2447.

Malcolm IA, Soulsby C, Hannah DM, Bacon PJ, Youngson AF, Tetzlaff D: The influence of riparian woodland on stream temperatures: implications for the performance of juvenile salmonids. Hydrol Processes 2008, 22: 968–979. 10.1002/hyp.6996

Elliott JM, Elliott JA: Temperature requirements of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar, brown trout Salmo trutta and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus: predicting the effects of climate change. J Fish Biol 2010, 77: 1793–1817. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02762.x

Hari R, Livingstone DM, Siber R, Burkhardt-Holm P, Guttinger H: Consequences of climatic change for water temperature and brown trout populations in alpine rivers and streams. Glob Chang Biol 2006, 12: 10–26. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001051.x

Morrison C, Hero JM: Geographic variation in life-history characteristics of amphibians: a review. J Anim Ecol 2003, 72: 270–279. 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00696.x

Durance I, Ormerod SJ: Climate change effects on upland stream macroinvertebrates over a 25-year period. Glob Chang Biol 2007, 13: 942–957. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01340.x

Pusey BJ, Arthington AH: Importance of the riparian zone to the conservation and management of freshwater fish: a review. Mar Freshw Res 2003, 54: 1–16. 10.1071/MF02041

Moore RD, Spittlehouse DL, Story A: Riparian microclimate and stream temperature response to forest harvesting: a review. J Am Water Resour Assoc 2005, 41: 813–834.

Ward JV: Thermal characteristics of running waters. Hydrobiologia 1985, 125: 31–46. 10.1007/BF00045924

Caissie D: The thermal regime of rivers: a review. Freshw Biol 2006, 51: 1389–1406. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2006.01597.x

Hannah DM, Malcolm IA, Soulsby C, Youngson AF: Heat exchange and temperatures within a salmon spawning stream in the Cairngorms, Scotland: seasonal and sub-seasonal dynamics. River Res Appl 2004, 20: 635–652. 10.1002/rra.771

Webb BW, Hannah DM, Moore RD, Brown LE, Nobilis F: Recent advances in stream and river temperature research. Hydrol Processes 2008, 22: 902–918. 10.1002/hyp.6994

Naiman RJ, Decamps H: The ecology of interfaces: riparian zones. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1997, 28: 621–658. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.621

Young K: A review and meta-analysis of the effects of riparian zone logging on stream ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest. Centre for Applied Conservation Research, Forest Sciences Department, University of British Columbia, Vancouver; 2001.

Belsky AJ, Matzke A, Uselman S: Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 1999, 54: 419–431.

Hannah DM, Webb BW, Nobilis F: River and stream temperature: dynamics, processes, models and implications. Hydrol Processes 2008, 22: 899–901. 10.1002/hyp.6997

Osborne LL, Kovacic DA: Riparian vegetated buffer strips in water quality restoration and stream management. Freshw Biol 1993, 29: 243–258. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1993.tb00761.x

Haycock NE, Muscutt AD: Landscape management strategies for the control of diffuse pollution. Landscape and Urban Planning 1995, 31: 313–321. 10.1016/0169-2046(94)01056-E

Wilby RL, Orr H, Watts G, Battarbee RW, Berry PM, Chadd R, Dugdale SJ, Dunbar MJ, Elliott JA, Extence C, Hannah DM, Holmes N, Johnson AC, Knights B, Milner NJ, Ormerod SJ, Solomon D, Timlett R, Whitehead PJ, Wood PJ: Evidence needed to manage freshwater ecosystems in a changing climate: Turning adaptation principles into practice. Sci Total Environ 2010, 408: 4150–4164. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.05.014

Bowler D, Hannah D, Orr H, Pullin S: What are the effects of wooded riparian zones on stream temperatures and stream biota?. Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, ; 2008. . http://www.environmentalevidence.org/Documents/Final_protocols/Protocol45.pdf

Parkyn SM, Davies-Colley RJ, Halliday NJ, Costley KJ, Croker GF: Planted riparian buffer zones in New Zealand: do they live up to expectations? Restor Ecol 2003, 11: 436–447. 10.1046/j.1526-100X.2003.rec0260.x

Broadmeadow SB, Jones JG, Langford TEL, Shaw PJ, Nisbet TR: The influence of riparian shade on lowland stream water temperatures in southern England and their viability for brown trout. River Res Appl 2011, 27: 226–237. 10.1002/rra.1354

Wilkerson E, Hagan JM, Darlene S, Whitman AA: The effectiveness of different buffer widths for protecting headwater stream temperature in Maine. Forest Sci 2006, 52: 221–231.

Shrimpton JM, Bourgeois JF, Quigley JT, Blouw DM: Removal of the Riparian Zone during Forest Harvesting: Are the Effects Cumulative Downstream? In Proceedings of a Conference on the Biology and Management of Species and Habitats at Risk, Kamloops, B.C., 15–19 Feb,1999. Volume Two. Edited by: Darling LM. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Victoria, B.C. and University College of the Cariboo, Kamloops; 2000.

Lynch JA, Rishel GB, Corbett ES: Thermal Alteration of Streams Draining Clear-Cut Watersheds - Quantification and Biological Implications. Hydrobiologia 1984, 111: 161–169. 10.1007/BF00007195

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315: 629. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Curry RA, Scruton DA, Clarke KD: The thermal regimes of brook trout incubation habitats and evidence of changes during forestry operations. Can J For Res 2002, 32: 1200–1207. 10.1139/x02-046

Keim RE, Schoenholtz SH: Functions and effectiveness of silvicultural streamside management zones in loessial bluff forests. For Ecol Manage 1999, 118: 197–209. 10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00499-X

Kiffney PM, Richardson JS, Bull JP: Responses of periphyton and insects to experimental manipulation of riparian buffer width along forest streams. J Appl Ecol 2003, 40: 1060–1076. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2003.00855.x

Brown GW: Swank GW. Water temperature in the Steamboat Drainage. USDA Forest Service Research Paper, Rothacher J; 1971.

Graynorth E: Effects of logging on stream environments and faunas in Nelson. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 1979, 13: 79–109. 10.1080/00288330.1979.9515783

Bott TL, Newbold JD, Arscott DB: Ecosystem metabolism in Piedmont streams: reach geomorphology modulates the influence of riparian vegetation. Ecosystems 2006, 9: 398–421. 10.1007/s10021-005-0086-6

Dineen G, Harrison SSC, Giller PS: Growth, production and bioenergetics of brown trout in upland streams with contrasting riparian vegetation. Freshw Biol 2007, 52: 771–783. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01698.x

Harding JS, Claassen K, Evers N: Can forest fragments reset physical and water quality conditions in agricultural catchments and act as refugia for forest stream invertebrates? Hydrobiologia 2006, 568: 391–402. 10.1007/s10750-006-0206-0

Rutherford JC, Davies-Colley RJ, Quinn JM, Stroud MJ, Cooper AB: Stream shade: towards a restoration strategy. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand; 1999.

Sabater S, Armengol J, Comas E, Sabater F, Urrizalgui I, Urrutia I: Algal biomass in a disturbed Atlantic river: water quality relationships and environmental implications. Sci Total Environ 2000, 263: 185–195. 10.1016/S0048-9697(00)00702-6

Storey RG, Cowley DR: Recovery of three New Zealand rural streams as they pass through native forest remnants. Hydrobiologia 1997, 353: 63–76. 10.1023/A:1003042425431

Tait CK, Li JL, Lamberti GA, Pearsons TN, Li HW: Relationships between Riparian Cover and the Community Structure of High Desert Streams. J N Am Bentholl Soc 1994, 13: 45–56. 10.2307/1467264

Webb BW, Crisp DT: Afforestation and stream temperature in a temperate maritime environment. Hydrol Processes 2006, 20: 51–66. 10.1002/hyp.5898

Boegh E, Olsen M, Conallin J, Holmes E: Modelling the spatial variations of stream temperature and its impacts on habitat suitability in small lowland streams. 328th edition. IAHS Publ, Hyderabad, India; 2009. September 2009)

Brown LE, Holden CL, Ramchunder SJ: A comparison of stream water temperature regimes from open and afforested moorland, Yorkshire Dales, northern England. Hydrol Processes 2010, 24: 3206–3218. 10.1002/hyp.7746

Buisson L, Blan L, Grenouillet G: Modelling stream fish species distribution in a river network: the relative effects of temperature versus physical factors. Ecol Freshw Fish 2008, 17: 244–257. 10.1111/j.1600-0633.2007.00276.x

Graham CT, Harrod C: Implications of climate change for the fishes of the British Isles. J Fish Biol 2009, 74: 1143–1205. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02180.x

Baillie BR, Collier KJ, et al.: Effects of forest harvesting and woody-debris removal on two Northland streams, New Zealand. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 2005,39(1):1–15. 10.1080/00288330.2005.9517290

Banks JL, Li J, et al.: Influence of clearcut logging, flow duration, and season on emergent aquatic insects in headwater streams of the Central Oregon Coast Range. J N Am Bentholl Soc 2007, 26: 620–632. 10.1899/06-104.1

Brown GW, Krygier JT: Effects of clear-cutting on stream temperature. Water Resour Res 1970,6(4):1133–9. 10.1029/WR006i004p01133

Brownlee MJ, Shepherd BG, et al.: Some Effects of Forest Harvesting on Water Quality in the Slim Creek Watershed in the Central Interior of British Columbia Canada.". Can Tech Rep Fish Aquat Sci 1988, 1613: I-V. 1–41

Burton TM, Likens GE: The effect of strip-cutting on stream temperatures in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, New Hampshire. Bioscience 1973,23(7):433–435. 10.2307/1296545

Fowler WB, Helvey JD, et al.: Hydrologic and climatic changes in three small watersheds after timber harvest. USDA Forest Service, Portland, Oregon, USA; 1987:ii + 13.

Garman GC, Moring JR: Initial effects of deforestation on physical characteristics of a boreal river. Hydrobiologia 1991,209(1):29–37. 10.1007/BF00006715

Hartman G, Scrivener JC, et al.: "Some effects of different streamside treatments on physical conditions and fish population processes in Carnation Creek, a coastal rain forest stream in British Columbia.". In Streamside management: forestry and fishery interactions. Edited by: Salo Ernest O, Terrance W. , ; :330–372. maps

Jackson CR, Sturm CA, et al.: Timber harvest impacts on small headwater stream channels in the coast ranges of Washington. J Am Water Resour Assoc 2001,37(6):1533–1549. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2001.tb03658.x

Keim RE, Schoenholtz SH: Functions and effectiveness of silvicultural streamside management zones in loessial bluff forests. Forest Ecol Manage 1999,118(1–3):197–209.

Likens GE, Bormann FH, et al.: Effects of forest cutting and herbicide treatment on nutrient budgets in the Hubbard Brook watershed-ecosytem. Ecol Monogr 1970,40(1):23–47. 10.2307/1942440

Lynch JA, Rishel GB, et al.: Thermal alteration of streams draining clear-cut watersheds - quantification and biological implications. Hydrobiologia 1984,111(3):161–169. 10.1007/BF00007195

Mellina E: "Stream temperature responses to clearcut logging in the central interior of British Columbia: test of the predictive model developed by Mellina et al. (2002)." Mountain Pine Beetle Initiative Working Paper - Pacific Forestry Centre. Canadian Forest Service(No.2006–8), ; 2006:.

Mellina E, Moore RD, et al.: Stream temperature responses to clearcut logging in British Columbia: the moderating influences of groundwater and headwater lakes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 2002,59(12):1886–1900. 10.1139/f02-158

Moore RD, Sutherland P, et al.: Thermal regime of a headwater stream within a clear-cut, coastal British Columbia, Canada. Hydrol Processes 2005,19(13):2591–2608. 10.1002/hyp.5733

Musslewhite J, Wipfli MS: "Effects of alternatives to clearcutting on invertebrate and organic detritus transport from headwaters in Southeastern Alaska." General Technical Report - Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service(No.PNW-GTR-602). , ; 2004:i + 28.

Quinn JM, Boothroyd IKG, et al.: "Riparian buffers mitigate effects of pine plantation logging on New Zealand streams 2. invertebrate communities. Forest Ecol Manage 2004,191(issues 1–3):129–146.

Rayne S, Henderson G, et al.: Riparian forest harvesting effects on maximum water temperatures in wetland-sourced headwater streams from the Nicola River Watershed, British Columbia, Canada. Water resources management 2008,22(5):565–578. 10.1007/s11269-007-9178-8

Rishel GB, Lynch JA, et al.: "Seasonal stream temperature changes following forest harvesting.". J Environ Qual 1982,11(1):112–116.

Swift LW, Messer JB: Forest cuttings raise temperatures of small streams in the southern Appalachians. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation in India 1971,26(3):111–6.

Young KA, Hinch SG, et al.: Status of resident coastal cutthroat trout and their habitat twenty-five years after riparian logging. North Am J Fish Manage 1999,19(4):901–911. 10.1577/1548-8675(1999)019<0901:SORCCT>2.0.CO;2

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Diamond for his input to the planning stages of this review and James Bussell and Diane Jones for their assistance in the conduct of the review. We thank Bruce Webb for kindly supplying data. This review was part supported by the UK Environment Agency and a UK Natural Environment Research Council Grant (REF NE/C508734/2) to ASP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in drafting/revising the manuscript. DB and RM performed the databases searches. DB extracted and analyzed the data. AS conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13750_2011_2_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Original search and updated search results. Results of the number of hits obtained for different keyword and database searches during the original and updated search. (DOCX 31 KB)

13750_2011_2_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Characteristics of group 1 studies. Characteristics of studies comparing water temperatures in streams with and without buffer strips/riparian cover. (DOC 43 KB)

13750_2011_2_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional file 3: Forest plots of group 1 studies. Forest plots of data from studies comparing water temperatures in streams with and without buffer strips/riparian cover. (DOC 42 KB)

13750_2011_2_MOESM4_ESM.docx

Additional file 4: Characteristics of group 2 studies. Characteristics of studies comparing stream temperatures in open and forested landscapes. (DOCX 85 KB)

13750_2011_2_MOESM5_ESM.doc

Additional file 5: Forest plots of group 2 studies. Forest plots of data from studies comparing stream temperatures in open and forested landscapes. (DOC 39 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bowler, D.E., Mant, R., Orr, H. et al. What are the effects of wooded riparian zones on stream temperature?. Environ Evid 1, 3 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-2382-1-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-2382-1-3