Abstract

Background

Cryptosporidium and Giardia are important causes of diarrhea diseases in humans and animals worldwide, and both of them are transmitted by the fecal–oral route, either by direct contact or by the ingestion of contaminated food or water. The role of flies in the mechanical transmission of Cryptosporidium and Giardia has been receiving increasing attention. To date, no information is available in China about the occurrence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in flies. We here investigated Cryptosporidium and Giardia in flies on dairy farms in Henan Province, China, at the genotype and subtype levels.

Methods

Eight hundred flies were randomly collected from two dairy farms from July 2010 to September 2010 and were divided evenly into 40 batches. The fly samples were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia with nested PCR. Cryptosporidium was genotyped and subtyped by analyzing the DNA sequences of small subunit rRNA (SSU rRNA) and 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) genes, respectively. The identity of Giardia was determined by sequence analyzing of the triosephosphate isomerase (tpi), glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh), and β-giardin (bg) genes.

Results

Forty batches of flies had 10% of contamination with Cryptosporidium or Giardia, with a mixed infection of the two parasites in one batch of flies. The Cryptosporidium isolates were identified as C. parvum at the SSU rRNA locus, and all belonged to subtype IIdA19G1 at the gp60 locus. The Giardia isolates were all identified as assemblage E of G. duodenalis at the tpi, gdh, and bg loci. One novel subtype of assemblage E was identified based on the gdh and bg loci.

Conclusions

This is the first molecular study of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in flies identified at both genotype and subtype levels. SSU rRNA and gp60 sequences of C. parvum in flies was 100% homologous with those derived from humans, suggesting flies act as an epidemiological vector of zoonotic cryptosporidiosis. The variable PCR efficiencies observed in the analysis of Giardia at different loci suggest that we should use the multilocus genotyping tool in future studies to increase the detection rate, and importantly, to obtain more complete genetic information on Giardia isolates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cryptosporidium and Giardia are commonly regarded as zoonotic parasites responsible for diarrheal diseases in humans worldwide. The diarrhea caused by cryptosporidiosis may become profuse and chronic, depending on the health status of the host, and appears to be life-threatening in people with various immune-system deficiencies. Many studies have confirmed the high mortality associated with Cryptosporidium infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection [1–4]. A single Cryptosporidium oocyst has been reported to initiate infection in immunosuppressed persons. Similarly, the pathogen also debilitates immunocompetent persons in whom the disease can be caused by as few as 10 oocysts [5]. The 50% infectious dose (ID50) of geographically diverse isolates of C. parvum for immunocompetent people ranges from 9 to 1,042 oocysts [6]. The pathogenicity of Giardia is generally considered to be less severe in humans than that of Cryptosporidium, but the parasite can lead to growth and developmental retardation in children through malnutrition, even in asymptomatic cases [7].

The broad zoonotic aspects of these diseases complicate the epidemiology of both cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis because both occur in a wide range of reservoir hosts. Both these parasites can persist for long periods of time in the environment (i.e., in water, soil, on vegetation and other food resources) and maintain their infectivity even under harsh environmental conditions [8]. People acquire cryptosporidiosis or giardiasis by digesting oocysts or cysts excreted from infected hosts, respectively, mainly through either direct host-to-host contact or indirectly by the consumption of contaminated water or food [9, 10]. Water- and food-borne cases and outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis have been extensively documented in several countries and regions [11–22]. However, in analyses of the correlative risk factors for the two parasitic diseases, especially during food-borne outbreak events involving Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts, flies have drawn attention because of their role in the mechanical transmission of these food-borne infections.

When researchers consider the vehicles that transport these parasites between feces and food, flies are of greater concern than other arthropods (such as cockroaches and dung beetles) because of the huge numbers of flies in the environment, especially in locations where contaminated human and animal feces are readily accessible to them, such as in rural livestock-raising areas. Outbreaks of food-borne diarrheal diseases display distinct seasonal patterns, which coincide with seasonal increases in the abundance of flies during the warm months of the year [23]. The control of flies is closely related to declines in the numbers of outbreaks and human cases of food-borne diseases [24]. Several studies have confirmed that the fly is involved in the mechanical transmission of C. parvum and G. duodenalis in a variety of settings, and have demonstrated that flies can act as mechanical vectors [23, 25–35]. Flies can carry Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts on their body surfaces (exoskeletons) and in their digestive tracts because of their vagility and feeding mechanisms [23, 25, 29, 35]. Flies are also reported to be able to carry 4–131 Cryptosporidium oocysts each for at least three weeks, and the oocysts deposited by them have been shown to be infectious in mice [34]. Although G. duodenalis cysts have been reported in flies, their viability and infectivity have not been determined.

Cattle manure is a favorite breeding place, food source, and landing site for filth flies. It has been reported that cattle barns are sites at which house flies can reproduce throughout the winter or can overwinter [34]. In China, currently there are no reports of flies carrying Cryptosporidium or Giardia. The aims of the present study were to determine the occurrence of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in flies captured on dairy farms, and to assess the role of flies as vectors in the transmission of cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis by genotyping and subtyping tools.

Methods

Sites and methods of collecting flies

The flies analyzed in the present study were captured on two dairy farms in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, where all preweaned calves were kept and where livestock infecting with Cryptosporidium and Giardia are known to occur. Collection began on 10 July 2010 and lasted until 25 September 2010; the average air temperature was 27-32°C and the relative humidity was 35%-90%. Briefly, four fly-catching papers (Dahao Daily Chemicals Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China) were set at different locations in each barn. The flies were taken from the papers with forceps at 3-4-day intervals [34]. Eight hundred of the flies were randomly selected, counted, and divided into batches of 20. Among which, more than 90% of files belonged to Musca domestica, and only a small number of them were Chrysomya megacephala and Sarcophaga sp. Each batch was resuspended separately in a 10-ml tube in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, transported to the laboratory in a cooler with ice packs, and stored at 4°C until processing.

Processing flies for oocysts/cysts

The 40 batches of flies were each ground in a mortar until crushed so that the parasites they carried internally were released into the homogenates [29]. The homogenates were then immediately filtered with a 198 μm sieve, and the filtrates were centrifuged at 1500× g for 5 min at room temperature. This ensured the recovery of the particles derived from the exoskeletons and digestive tracts of the flies in the sedimented debris.

DNA extraction

The genomic DNA of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from the fly-derived debris was extracted from 100 mg of processed sample using the E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit (Omega Biotek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer-recommended procedure. The eluted DNA (200 μl) was stored at −20°C until its analysis with PCR.

Genotyping and subtyping Cryptosporidium and Giardia

All DNA preparations were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium DNA with the nested PCR amplification of an approximately 830 bp fragment of the SSU rRNA gene, and were identified to the species/genotype level as previously described by Xiao et al.[36]. The C. parvum-positive samples were subtyped with the nested PCR amplification of an approximately 850 bp fragment of the gp60 gene, as previously described by Alves et al.[37].

The G. duodenalis genotypes and subtypes were determined with three distinct protocols using nested PCRs targeting the tpi, gdh, and bg genes of the parasite; fragments of approximately 530 bp, 530 bp, and 510 bp, respectively, were amplified corresponding to the partial genes [38–41].

Each DNA preparation was performed three times by using 2 μl of DNA per PCR. All the nested PCR products described above were visualized by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide before sequencing.

DNA sequence analysis

All secondary PCR products were sequenced using the secondary PCR primers on an ABI PRISM™ 3730xl DNA Analyzer using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The accuracy of the sequencing data was confirmed by sequencing in both directions, and further PCR products were sequenced if necessary for some DNA preparations. The genotype and subtype identities of the Cryptosporidium and G. duodenalis isolates were established with direct comparisons, using ClustalX 1.83, of the acquired nucleotide sequences with each other and with reference sequences downloaded from GenBank.

Results

Distribution of Cryptosporidium and Giardia on the two dairy farms

Overall, 10% of the batches of flies were contaminated by one or other of the two parasites, with a mixed infection of them both in one sample (Table 1). However, the rates of occurrence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in the batches of flies differed on the two farms. The occurrence of Giardia was higher than that of Cryptosporidium in the batches of flies on Farm A, with Giardia in 15% (3/20) of batches and Cryptosporidium in 10% (2/20) of batches. In contrast, more batches of flies carried Cryptosporidium (10%, 2/20) than carried Giardia (5%, 1/20) on Farm B.

Genotyping and subtyping Cryptosporidium

Forty batches of flies were all screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium using PCR amplification of the SSU rRNA gene. Four samples (two at each farm) were positive for Cryptosporidium and were identified as C. parvum. The four C. parvum sequences were identical to each other and had 100% homology to previous isolates derived from cattle [GenBank: HQ009805, AB513857-AB513881, AB441687, EF611871, AF093493, and JX416362] and humans [GenBank: EU331237-EU331241, DQ523504, and DQ656352]. At the gp60 locus, all four C. parvum isolates produced the expected PCR product, which was successfully sequenced. They all belonged to subtype IIdA19G1 and shared 100% homology with previous sequences of subtype IIdA19G1 derived from cattle [GenBank: HQ009809 and JX416369] and humans [GenBank: DQ280496 and JF691561].

Genotyping and subtyping G. duodenalis

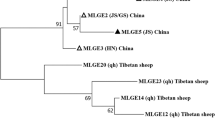

Three, four, and four of the 40 batches of flies were identified as assemblage E of G. duodenalis at the tpi, gdh, and bg loci, respectively. At the tpi locus, the three tpi nucleotide sequences were identical and belonged to G. duodenalis assemblage E (accession number KJ009339), which has been reported in cattle [GenBank: EF654686 and KC778540], sheep [GenBank: JF792416 and JF792421], and goats [GenBank: HQ283233, EU189328, EU189333-EU189340, EU189343, EU189344, EU189349, EU189351-EU189353, EU189355, and EU189356]. Novel subtypes of assemblage E were found at the gdh and bg loci. The four gdh and four bg assemblage E sequences (accession number KJ009340 for the gdh gene and KJ009341 for the bg gene) were identical to each other, but shared only 99.8% homology with the previously reported sequences of goat-derived G. duodenalis isolates [GenBank: AY826198 and DQ116624].

Discussion

Human intestinal parasites are relatively common worldwide, especially in the rural areas of developing countries because of poverty, poor environmental hygiene, and inadequate health services. In Spain, the prevalence of human cryptosporidiosis in hospitals is higher in patients from rural districts (3.4%, 23/675) than in those from urban areas (1.2%, 17/1429), and these results may be related to the general presence of flies, which naturally harbor Cryptosporidium oocysts, in rural areas [31]. It has been confirmed in field studies and laboratory experiments that flies carry human parasites on their exoskeletons and in their digestive tracts, including Cryptosporidium and Giardia[28, 42]. Because Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts are common in the environment, flies, especially coprophagous flies, may be involved in the mechanical dissemination of the parasites via their exoskeletons, fecal deposition, and regurgitation after contact with infected materials. They then deposit these oocysts/cysts on the surfaces they visit. Filth flies are reported to have the capacity to travel up to 20 miles [29], and a positive relationship has been demonstrated between the abundance of flies at a specific site and the number of Cryptosporidium oocysts carried by them [27]. The transmission of human pathogens by adult flies has been reported to occur via mechanical dislodgment [28].

In this study, 40 batches of flies had 10% of infection rate for Cryptosporidium and Giardia by molecular methods. Previously, variable infection rates for both these parasites have been reported in flies conducted in five countries. The occurrence of Cryptosporidium in flies ranges from 1.81% to 83.3%, and of Giardia ranges from 3.34% to 84% (Table 2). The infection rates are complicated and are probably affected by many factors, including the collection site, sample size, sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic technique, and so on. In addition, differences in collection seasons and the sites of fly capture might also influence the infection rates of the parasites, because environmental temperature and humidity directly affect the growth and development of flies, resulting in changes in the numbers and vitality of flies. Seasonal increases in the abundance of flies during the warm months of the year are well known. Outbreaks of food-borne diarrheal diseases show seasonal fluctuations, which accord with the seasonal changes in fly numbers [23]. Flies tend to feed on and breed in filth, especially animal manure and human excrement. There is also a close relationship between the environments at the collection sites and the fly populations. A study of the potential role of flies as a transport host for Cryptosporidium spp. in different filth conditions, conducted in Ethiopia, found that Musca domestica was more abundant in dairy cow barns than at other sites. In contrast, the number of Musca sorbens was greater at defecation grounds and in market areas [27]. This might be related to preference differences for breeding places and food sources in different fly populations.

In the present study, the subtype IIdA19G1 identified in flies was identical to the cattle-derived isolates from the same dairy farms investigated [43]. Although the normal PCR used in the present study did not assess the viability of the oocysts in the flies, many previous studies have reported that viable C. parvum oocysts are present on the body surfaces/exoskeletons and in the digestive tracts of flies [23, 29, 35]. Thus, flies undoubtedly increase the risk to humans of infection with Cryptosporidium spp. and the cross-transmission to susceptible animal hosts, no matter where they occur in the flies. The molecular results described above not only provide powerful evidence of the mechanical transmission of these parasites by flies, acting as the transport hosts of Cryptosporidium in the dissemination of human cryptosporidiosis, but also allow us to assess the potential zoonotic transmission of cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidium parvum isolates from flies in the areas investigated were genetically identical to the human-derived C. parvum isolates from other countries at both the SSU rRNA locus and the gp60 locus [44–48], implying its potential zoonotic transmission and its significance for public health. Because there is a lack of epidemiological data about human cases of cryptosporidiosis in the investigated areas, it is unclear whether the disease burden of human cryptosporidiosis is attributable to parasites of animal origin, and especially whether filth flies are involved in its mechanical transport. More systematic and complete epidemiological data are required from humans and animals in the areas investigated.

Although the three assemblage E isolates identified at the tpi locus had 100% similarity to those from cattle, sheep, and goats [49–52], new subtypes (different to isolates from other countries or areas) were detected at the gdh and bg loci, and shared 100% homology to those obtained from calves in the two dairy cattle farms investigated (data for cattle-derived G. duodenalis isolates unpublished). Thus, these findings demonstrate not only the natural occurrence of flies contaminated with G. duodenalis cysts, but also the endemic genetic characterization of G. duodenali s assemblage E in the dairy cattle in Henan, China. Previously, numerous molecular epidemiological data have shown the strong host specificity and narrow host range of assemblage E, which is predominantly found in cloven-hoofed domestic mammals, including cattle, water buffaloes, sheep, and pigs [17]. Flies contaminated with assemblage E G. duodenalis could increase the possibility of repeated infection or cross-transmission between these susceptible animals by mechanical transmission. However, the finding of flies carrying assemblage E does not pose a serious threat to the local inhabitants because assemblage E has currently only been isolated from three Egyptians [53]. In the present study, we detected no assemblage A or B G. duodenalis in flies, which are considered to be the two major assemblages causing human giardiasis. These results might reflect the lack or low frequencies of assemblages A and B in cattle, and may also be related to the relatively small numbers of infected flies detected. This study is the first molecular description of G. duodenalis isolates in flies at the genotype and subtype levels based on the tpi, gdh, and bg genes. Until now, in assessing the role of flies as vectors for the mechanical transmission of human giardiasis, only four other studies have identified G. duodenali s isolates in flies with molecular techniques, but the isolates were not genotyped [23, 29, 32, 35].

Conclusion

The occurrence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in flies (Musca domestica is the major species) in China was first confirmed by molecular methods at both the genotype and subtype levels. The SSU rRNA and gp60 sequences of C. parvum identified in flies were identical with animal and human isolates indicating that flies can act as an epidemiological link in zoonotic cryptosporidiosis. The variable PCR efficiencies at different loci of Giardia imply that we should use the MLG tool in future studies, because it could not only trace the infection or contamination source of G. duodenalis but also increase the detection rate. Although no disease outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium or Giardia have been related to flies, flies carrying one or other of these parasites will significantly affect human health because of the huge numbers of flies in the environment. The proportions of human cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis that can be attributed to zoonotic transmission involving flies must be assessed using systematic molecular epidemiological data from humans and animals in these areas in the future.

References

Goldstein ST, Juranek DD, Ravenholt O, Hightower AW, Martin DG, Mesnik JL, Griffiths SD, Bryant AJ, Reich RR, Herwaldt BL: Cryptosporidiosis: an outbreak associated with drinking water despite state-of-the-art water treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1996, 124: 459-468. 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00001.

Mor SM, DeMaria A, Griffiths JK, Naumova EN: Cryptosporidiosis in the elderly population of the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 48: 698-705. 10.1086/597033.

Nahrevanian H, Assmar M: Cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008, 41: 74-77.

Sodqi M, Marih L, Lahsen AO, Bensghir R, Chakib A, Himmich H, El Filali KM: Causes of death among 91 HIV-infected adults in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. Presse Med. 2012, 41: e386-e390. 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.12.013. (in French)

Graczyk TK, Fayer R, Cranfield MR: Zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium parvum: Implications for water-borne cryptosporidiosis. Parasitol Today. 1997, 13: 348-351. 10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01076-4.

Okhuysen PC, Chappell CL, Crabb JH, Sterling CR, DuPont HL: Virulence of three distinct Cryptosporidium parvum isolates for healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 1999, 180: 1275-1281. 10.1086/315033.

Prado MS, Cairncross S, Strina A, Barreto ML, Oliveira-Assis AM, Rego S: Asymptomatic giardiasis and growth in young children; a longitudinal study in Salvador, Brazil. Parasitology. 2005, 131: 51-56. 10.1017/S0031182005007353.

Siński E, Behnke JM: Apicomplexan parasites: environmental contamination and transmission. Pol J Microbiol. 2004, 53: 67-73. 10.1099/jmm.0.04994-0.

Xiao L, Ryan UM: Cryptosporidiosis: an update in molecular epidemiology. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004, 17: 483-490. 10.1097/00001432-200410000-00014.

Smith HV, Cacciò SM, Tait A, McLauchlin J, Thompson RC: Tools for investigating the environmental transmission of Cryptosporidium and Giardia infections in humans. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22: 160-167. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.009.

Fayer R: Cryptosporidium: a water-borne zoonotic parasite. Vet Parasitol. 2004, 126: 37-56. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.004.

Karanis P, Kourenti C, Smith H: Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: a worldwide review of outbreaks and lessons learnt. J Water Health. 2007, 5: 1-38. 10.2166/wh.2006.002.

Semenza JC, Nichols G: Cryptosporidiosis surveillance and water-borne outbreaks in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2007, 12: E13-E14.

Robertson LJ, Forberg T, Gjerde BK: Giardia cysts in sewage influent in Bergen, Norway 15–23 months after an extensive waterborne outbreak of giardiasis. J Appl Microbiol. 2008, 104: 1147-1152. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03630.x.

Cheun HI, Kim CH, Cho SH, Ma DW, Goo BL, Na MS, Youn SK, Lee WJ: The first outbreak of giardiasis with drinking water in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2013, 4: 89-92. 10.1016/j.phrp.2013.03.003.

Moon S, Kwak W, Lee S, Kim W, Oh J, Youn SK: Epidemiological characteristics of the first water-borne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in Seoul, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013, 28: 983-989. 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.7.983.

Feng Y, Xiao L: Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011, 24: 110-140. 10.1128/CMR.00033-10.

Bean NH, Goulding JS, Lao C, Angulo FJ: Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks–United States, 1988–1992. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1996, 45: 1-66.

Dietz V, Vugia D, Nelson R, Wicklund J, Nadle J, McCombs KG, Reddy S: Active, multisite, laboratory-based surveillance for Cryptosporidium parvum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 62: 368-372.

Wallace DJ, Van Gilder T, Shallow S, Fiorentino T, Segler SD, Smith KE, Shiferaw B, Etzel R, Garthright WE, Angulo FJ: Incidence of foodborne illnesses reported by the foodborne diseases active surveillance network (FoodNet)-1997. FoodNet Working Group. J Food Prot. 2000, 63: 807-809.

Budu-Amoako E, Greenwood SJ, Dixon BR, Barkema HW, McClure JT: Foodborne illness associated with Cryptosporidium and Giardia from livestock. J Food Prot. 2011, 74: 1944-1955. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-107.

Smith HV, Cacciò SM, Cook N, Nichols RA, Tait A: Cryptosporidium and Giardia as foodborne zoonoses. Vet Parasitol. 2007, 149: 29-40. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.07.015.

Graczyk TK, Grimes BH, Knight R, Da Silva AJ, Pieniazek NJ, Veal DA: Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia carried by synanthropic flies by combined fluorescent in situ hybridization and a monoclonal antibody. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 68: 228-232.

Graczyk TK, Knight R, Gilman RH, Cranfield MR: The role of non-biting flies in the epidemiology of human infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2001, 3: 231-235. 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01371-5.

Getachew S, Gebre-Michael T, Erko B, Balkew M, Medhin G: Non-biting cyclorrhaphan flies (Diptera) as carriers of intestinal human parasites in slum areas of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2007, 103: 186-194. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.06.005.

Fetene T, Worku N: Public health importance of non-biting cyclorrhaphan flies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 103: 187-191. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.08.010.

Fetene T, Worku N, Huruy K, Kebede N: Cryptosporidium recovered from Musca domestica, Musca sorbens and mango juice accessed by synanthropic flies in Bahirdar, Ethiopia. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011, 58: 69-75. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01298.x.

Adenusi AA, Adewoga TO: Human intestinal parasites in non-biting synanthropic flies in Ogun State, Nigeria. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013, 11: 181-189. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2012.11.003.

Szostakowska B, Kruminis-Lozowska W, Racewicz M, Knight R, Tamang L, Myjak P, Graczyk TK: Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia recovered from flies on a cattle farm and in a landfill. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70: 3742-3744. 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3742-3744.2004.

Racewicz M, Kruminis-Łozowska W, Gabre RM, Stańczak J: The occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. in synanthropic flies in urban and rural environments. Wiad Parazytol. 2009, 55: 231-236. (in Polish)

Clavel A, Doiz O, Morales S, Varea M, Seral C, Castillo FJ, Fleta J, Rubio C, Gómez-Lus R: House fly (Musca domestica) as a transport vector of Cryptosporidium parvum. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2002, 49: 163-164.

Doiz O, Clavel A, Morales S, Varea M, Castillo FJ, Rubio C, Gómez-Lus R: House fly (Musca domestica) as a transport vector of Giardia lamblia. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2000, 47: 330-331.

Graczyk TK, Fayer R, Cranfield MR, Mhangami-Ruwende B, Knight R, Trout JM, Bixler H: Filth flies are transport hosts of Cryptosporidium parvum. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999, 5: 726-727. 10.3201/eid0505.990520.

Graczyk TK, Fayer R, Knight R, Mhangami-Ruwende B, Trout JM, Da Silva AJ, Pieniazek NJ: Mechanical transport and transmission of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts by wild filth flies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 63: 178-183.

Conn DB, Weaver J, Tamang L, Graczyk TK: Synanthropic flies as vectors of Cryptosporidium and Giardia among livestock and wildlife in a multispecies agricultural complex. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007, 7: 643-651. 10.1089/vbz.2006.0652.

Xiao L, Singh A, Limor J, Graczyk TK, Gradus S, Lal A: Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium oocysts in samples of raw surface water and wastewater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67: 1097-1101. 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1097-1101.2001.

Alves M, Xiao L, Sulaiman I, Lal AA, Matos O, Antunes F: Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41: 2744-2747. 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2744-2747.2003.

Sulaiman IM, Fayer R, Bern C, Gilman RH, Trout JM, Schantz PM, Das P, Lal AA, Xiao L: Triosephosphate isomerase gene characterization and potential zoonotic transmission of Giardia duodenalis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003, 9: 1444-1452. 10.3201/eid0911.030084.

Lalle M, Pozio E, Capelli G, Bruschi F, Crotti D, Cacciò SM: Genetic heterogeneity at the beta-giardin locus among human and animal isolates of Giardia duodenalis and identification of potentially zoonotic subgenotypes. Int J Parasitol. 2005, 35: 207-213. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.022.

Cacciò SM, De Giacomo M, Pozio E: Sequence analysis of the beta-giardin gene and development of a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to genotype Giardia duodenalis cysts from human faecal samples. Int J Parasitol. 2002, 32: 1023-1030. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00068-1.

Cacciò SM, Beck R, Lalle M, Marinculic A, Pozio E: Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages A and B. Int J Parasitol. 2008, 38: 1523-1531. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.04.008.

Xiao L, Fayer R: Molecular characterisation of species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium and Giardia and assessment of zoonotic transmission. Int J Parasitol. 2008, 38: 1239-1255. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.006.

Wang R, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang L, Jian F, Qi M, Ning C, Xiao L: Characteristics of Cryptosporidium transmission in preweaned dairy cattle in Henan, China. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 1077-1082. 10.1128/JCM.02194-10.

Kvác M, Kvetonová D, Sak B, Ditrich O: Cryptosporidium pig genotype II in immunocompetent man. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009, 15: 982-983. 10.3201/eid1506.071621.

Abreu-Acosta N, Quispe MA, Foronda-Rodrı’guez P, Alcoba-Florez J, Lorenzo-Morales J, Ortega-Rivas A, Valladares B: Cryptosporidium in patients with diarrhoea, on Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007, 101: 539-545. 10.1179/136485907X193798.

Meamar AR, Guyot K, Certad G, Dei-Cas E, Mohraz M, Mohammad K, Mehbod AA, Rezaie S, Rezaian M: Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans and animals in Iran. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007, 73: 1033-1035. 10.1128/AEM.00964-06.

Alves M, Xiao L, Antunes F, Matos O: Distribution of Cryptosporidium subtypes in humans and domestic and wild ruminants in Portugal. Parasitol Res. 2006, 99: 287-292. 10.1007/s00436-006-0164-5.

Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, Liu L, Feng Y, Xiao L: Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2013, 51: 557-563. 10.1128/JCM.02758-12.

Feng Y, Ortega Y, Cama V, Terrel J, Xiao L: High intragenotypic diversity of Giardia duodenalis in dairy cattle on three farms. Parasitol Res. 2008, 103: 87-92.

Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Firestone SM, McPhee S, Driessen N, Koehler AV, Haydon SR, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Stevens MA, Gasser RB: Assessing calves as carriers of Cryptosporidium and Giardia with zoonotic potential on dairy and beef farms within a water catchment area by mutation scanning. Electrophoresis. 2013, 34: 2259-2267. 10.1002/elps.201300146.

Gómez-Muñoz MT, Cámara-Badenes C, Martínez-Herrero Mdel C, Dea-Ayuela MA, Pérez-Gracia MT, Fernández-Barredo S, Santín M, Fayer R: Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in lambs from Spain reveals a high heterogeneity. Res Vet Sci. 2012, 93: 836-842. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.12.012.

Ruiz A, Foronda P, González JF, Guedes A, Abreu-Acosta N, Molina JM, Valladares B: Occurrence and genotype characterization of Giardia duodenalis in goat kids from the Canary Islands, Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2008, 154: 137-141. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.003.

Foronda P, Bargues MD, Abreu-Acosta N, Periago MV, Valero MA, Valladares B, Mas-Coma S: Identification of genotypes of Giardia intestinalis of human isolates in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2008, 103: 1177-1181. 10.1007/s00436-008-1113-2.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31330079), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1204328), Innovation Scientists and Technicians Troop construction Projects of Henan Province (134200510012), and the Program for Science and Technology Innovative Research Team in University of Henan Province (012IRTSTHN005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LXZ, AQL, and FCJ conceived and designed the experiments; ZFZ, HJD, MQ, JFZ, and HYW performed the experiments; RJW, WZ, SMZ, and GYC analyzed the data; AQL, LXZ, and RJW wrote the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Zifang Zhao, Haiju Dong contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Z., Dong, H., Wang, R. et al. Genotyping and subtyping Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis carried by flies on dairy farms in Henan, China. Parasites Vectors 7, 190 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-190

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-190