Abstract

Background

Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii is a primary vector of Plasmodium parasites in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. Adult females of An. cruzii and An. homunculus, which is a secondary malaria vector, are morphologically similar and difficult to distinguish when using external morphological characteristics only. These two species may occur syntopically with An. bellator, which is also a potential vector of Plasmodium species and is morphologically similar to An. cruzii and An. homunculus. Identification of these species based on female specimens is often jeopardised by polymorphisms, overlapping morphological characteristics and damage caused to specimens during collection. Wing geometric morphometrics has been used to distinguish several insect species; however, this economical and powerful tool has not been applied to Kerteszia species. Our objective was to assess wing geometry to distinguish An. cruzii, An. homunculus and An. bellator.

Methods

Specimens were collected in an area in the Serra do Mar hotspot biodiversity corridor of the Atlantic Forest biome (Cananeia municipality, State of Sao Paulo, Brazil). The right wings of females of An. cruzii (n= 40), An. homunculus (n= 50) and An. bellator (n= 27) were photographed. For each individual, 18 wing landmarks were subjected to standard geometric morphometrics. Discriminant analysis of Procrustean coordinates was performed to quantify wing shape variation.

Results

Individuals clustered into three distinct groups according to species with a slight overlap between representatives of An. cruzii and An. homunculus. The Mahalanobis distance between An. cruzii and An. homunculus was consistently lower (3.50) than that between An. cruzii and An. bellator (4.58) or An. homunculus and An. bellator (4.32). Pairwise cross-validated reclassification showed that geometric morphometrics is an effective analytical method to distinguish between An. bellator, An. cruzii and An. homunculus with a reliability rate varying between 78-88%. Shape analysis revealed that the wings of An. homunculus are narrower than those of An. cruzii and that An. bellator is different from both of the congeneric species.

Conclusion

It is possible to distinguish among the vectors An. cruzii, An. homunculus and An. bellator based on female wing characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Anopheles of the family Culicidae contains species that are widely distributed throughout South America [1]. These species are commonly associated with watercourses and forests, frequently in coastal areas. In Brazil, the primary anopheline species involved in Plasmodium transmission belong to two subgenera, i.e., Nyssorhynchus (Anopheles darlingi, An. aquasalis, An. nuneztovari s.l., An. oswaldoi, An. triannulatus s.l. and species of the An. albitarsis complex) [2, 3] and Kerteszia (An. cruzii, An. bellator and An. homunculus) [4], with An. cruzii and An. darlingi as the primary vectors of Plasmodium species [5]. The autochthonous transmission of extra-Amazonian malaria occurs mainly in areas of the Southeastern coastal Serra do Mar mountain range, where An. cruzii is a primary vector [6]. Anopheles homunculus and An. bellator are also important secondary vectors of human Plasmodium in that region [7, 8]. In this region, An. bellator, An. cruzii and An. homunculus occur in sympatry and are somewhat morphologically similar. Most Kerteszia species use bromeliad phytothelmata as larval habitats, with the exception of An. bambusicolus, whose habitat is water accumulated inside bamboo internodes [9].

According to Harrison et al.[10], the females of An. cruzii and An. homunculus can be distinguished by the scaling on maxillary palpomeres 3 and 4. In addition, Martins [11] showed that the integument of the abdominal terga in An. cruzii females are uniformly reddish or reddish with lighter portions, whereas the abdominal integument of An. homunculus are blackish with whitish areas. For larval differentiation, Lima [12] observed that the saddles of segment X are lightly sclerotised in An. cruzii, with either yellowish or reddish integument. By contrast, the larvae of An. homunculus have strongly pigmented saddles of segment X, with dark brown to blackish integument [13]. Anopheles bellator can be distinguished from An. cruzii and An. homunculus by the narrow apical pale bands on hind tarsomeres 2–4 (Figure 1), which are 30% or less of the length of the tarsomeres, and the typically entirely dark colouration of hind tarsomere 5; by contrast, hind tarsomeres 2–5 are 50% basal black and 50% apical pale in An. cruzii and An. homunculus[10]. The morphological identification of these species is often hampered by variability in the diagnostic characteristics and by damage to insect body parts caused by the capture procedure [13].

Recently published literature shows an increasing tendency towards assessing medically important insect species using geometric morphometrics [14–18], an analytical tool that allows for multivariate statistical descriptions of biological structures [19]. In insects, the wings are the main target for morphometrics because of their two-dimensional form and homologous vein patterns. In the present study, we used geometric morphometrics as a complementary and low-cost tool to identify vector species of the subgenus Kerteszia, focusing on three species that occur in areas of the coastal Atlantic Forest.

Methods

Biological sampling

All of the specimens were collected in an area of the Atlantic Forest biome in the municipality of Cananeia, State of São Paulo, Brazil, more specifically in the neighborhood of the Aroeira district (24°53’06” S / 47°51’01” W). Voucher specimens of An. cruzii and An. homunculus were deposited in the Coleção Entomológica de Referência, Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo (FSP-USP), Brazil. Mosquito larvae and pupae were taken from water that had accumulated in bromeliad tanks in 2009 and reared in the laboratory until adult emergence under standard conditions of temperature, food availability and container size. Adult females of An. bellator were captured in July and November 2011 with Shannon traps and preserved in plastic vials with silica gel. Species were identified based on colour pattern of larvae, according to Lima [12].

Material preparation and data acquisition

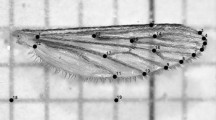

The right wings of females of An. cruzii (n = 40), An. homunculus (n = 50) and An. bellator (n = 27) were removed from adults and cured before being mounted on microscope slides. The wings were soaked for 12 hours in a 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution at room temperature to remove the wing scales. The potassium hydroxide was removed by washing the wings in a 20% solution of acetic acid. The wings were dyed with acid fuchsin for 60 minutes and then dehydrated in a series of ethanol concentrations ranging from 80% to 98%. Images of the wings were captured using a Leica DFC320 digital camera coupled to a Leica S6 microscope with 40X magnification. Eighteen wing landmarks (Figure 2) of each individual were digitised using the TpsDig software V.1.40 (QSC - James Rohlf), and the coordinate images were plotted onto a Cartesian plane for geometric descriptions. All of the wings were scanned twice, and the repeatability of the digitising procedure was assessed using statistical tests [20, 21]. The wing pictures were deposited in the CLIC Image Bank (http://bioinfo-prod.mpl.ird.fr/morphometrics/clic/declic/list.html).

Geometric morphometrics analysis

The wing size was estimated using isometric measurements of the centroid size [15, 22]. Generalised Procrustes analysis was performed to assess the wing shape. To describe the shape variation without the effects of allometry, a regression analysis was performed between the coordinates of the landmarks and the centroid size for each of the three species.

Discriminant analysis of the canonical variables was performed. To test the accuracy of species classification yielded by morphometrics, each individual was reclassified by comparing the shape with the overall mean wing size of each species using the Mahalanobis distances. The reclassification was cross-validated and the distances were estimated in discriminant axes in the absence of the individual to be classified. Thin-plate splines were obtained by regression of the canonical scores versus the shape components. The morphometric statistical analyses were conducted with the software TpsUtil 1.29, TpsRelw 1.39 (QSC - James Rohlf), MorphoJ 1.02 and Statistica 7.0. The graphics were generated using Statistica and MorphoJ 1.02.

Results

The mean centroid size of An. cruzii was 1.62 mm (range 1.45 - 1.77 mm), that of An. homunculus was 1.71 mm (range 1.60 - 1.93 mm), and that of An. bellator was 1.59 mm (range 1.46 - 1.77 mm). Only the mean centroid size of An. homunculus (Figure 3) was significantly different from those obtained for the other two species (P<0.001; ANOVA + Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test). The allometric effect was low (5.47%) but statistically significant (P<0.0001) and was removed from the shape analyses. A second round of analyses were conducted, with the allometric effect included, however, the results were essentially similar.

The canonical variate analysis for the wing shape showed that individuals clustered into distinct groups in the morphospace according to each species (Figure 4). Anopheles bellator was found to be isolated from the other species, whereas An. cruzii and An. homunculus slightly overlapped. The Procrustes distance between these two species was lower (3.50) than between An. cruzii and An. bellator (4.58) or between An. homunculus and An. bellator (4.32). The accuracy scores after a cross-validated reclassification test ranged from 78% to 88% (Table 1).

Thin-plate splines with pairwise comparison of species evidenced higher displacement of certain landmarks that were more informative for species identification (Figure 5). The greatest distinction between An. bellator and An. cruzii was found with landmarks 1, 17 and 18, whereas the distinction between An. bellator and An. homunculus was most clear using landmarks 1, 2, 3, 17 and 18. The main shape differences when comparing An. cruzii and An. homunculus were observed in landmarks 1, 2, 3, 12 and 13.

We noted that distances between some most-influential landmarks were also conspicuously distinct between species: distance between landmarks 13–14 (distance x); 12–13 (distance y); 2–13 (distance z); and 15–18 (distance w). Ratios between those distances are depicted in Figure 6, which allow one to diagnose the species based on a single value. The mean ratio between dimensions x and y was 0.97 for An. cruzii, 0.94 for An. homunculus and 0.61 for An. bellator (Figure 7), with An. bellator being significantly different from the other species (T-test, P<0.0001). The z/w ratio was 0.72 for An. cruzii, 0.74 for An. bellator and 0.63 for An. homunculus, with An. homunculus being significantly different from the other species (T-test, P<0.0001) (Figure 8).

Discussion

Adult females of An. homunculus and An. cruzii are morphologically similar; consequently, distinction between these species is generally problematic when using only the classical morphological characteristics described in identification keys [13]. The correct identification of species is essential for recognition of the vectors involved in the transmission of malaria and for helping researchers to develop control strategies [7]. Geometric morphometrics analyses revealed that An. homunculus, An. cruzii and An. bellator can be distinguished based on wing characteristics.

The results of the discriminant analysis showed that An. bellator is well separated from both An. cruzii and An. homunculus in the morphospace of the canonical variables. This finding is consistent with previous results indicating that An. bellator can be easily distinguished by the adult external morphology (hindtarsomere 5). However, one would expect higher phenotypic similarity between An. bellator and An. homunculus if the wing shape is directly associated with the close phylogenetic relationships between the species [23]. An. cruzii and An. homunculus, which are occasionally misidentified [9], were also discriminated despite partial overlapping in the morphospace of canonical variables.

The wing shape divergence among these three species was not as significant as that for species of the genera Culex and Aedes[16, 24], which may be a result of recent diversification of the subgenera [23] or due to evolutionary constraints. The close evolutionary relationships among Kerteszia representatives might be reflected in the wing shape because of the heritability of this structure, as proposed for other insects [12]. Anopheles bellator and An. homunculus can coexist in bromeliads and compete for resources [25], and this close association could impose constraints or favour canalisation to the observed phenotype.

Considering that the results obtained either with or without allometry were similar, we conclude that size variation did not interfere with species delimitation. Anopheles homunculus had the largest size among species in this study; however, we cannot ascertain that this comparison holds in nature because size is commonly subject to plasticity [15, 24, 26]. At least for An. homunculus and An. cruzii, it is plausible to consider that the size disparity may be associated with genetic determinism because both species were collected in the larval stage and reared to adults in the laboratory under similar environmental conditions and food resource availability.

Specimen collections were not simultaneous (years 2009 and 2011), what could lead us to believe that interspecific wing shape divergency may be partly a result of asynchronic sampling and microevolutionary changes. This idea is unlikely because the three-year interval is much shorter than the divergence time among the Anopheles species involved [23]. It has recently been reported that wing shape variation in Aedes albopictus can occur within four years [27] however, such variation is slight in comparison to macroevolutionary changes. Additionally, phenetic distance between Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus based on wing shape remained equivalent over several years [24].

In addition to helping taxonomists identify species, geometric morphometrics maybe used by health professionals to identify species in the future. This technique will not end up with other methods of identification, such as those based on the costal wing spots, but will complement them. Whereas present work was essentially based on wing landmarks, papers from Wilkerson and Peyton (1990) [28] and Motoki et al. (2009) [29] successfully used wing spot relative sizes to identify Anopheles species. Although it is not an easy task to simultaneously analyse landmarks and dark spots in Anopheles wings, we hope in a future to combine landmark and spot-based morphometrics, as suggested by Dujardin (personal communication: Jean Pierre Dujardin).

The mean ratio of dimensions x and y is 2/3 in An. bellator, whereas this ratio is nearly 1/1 in An. cruzii and An. homunculus. Remarkably, the length of segment 13–14 (distance x) in some individuals of An. bellator is so short that the segment is almost nonexistent. As far as we know, this vein pattern has not been observed in other culicids. Although the occasionally vestigial segment does not directly contribute to the diagnosis proposed here, it may be worth an investigation. As an example, the absence of a wing vein in Drosophila melanogaster was characterised as an informative mutation named crossveinless[30]. Additionally, the mean ratio z/w of An. homunculus was lower than those of the other two species. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 5, the wings of Anopheles homunculus are narrower anteroposteriorly.

Apart from the morphological characteristics used in this study, molecular taxonomic markers have been developed for Kerteszia species [13], facilitating species identification and delimitation. The employment of geometric morphometric methods in taxonomic studies is promising and should be performed in conjunction with other methods to facilitate the correct identification of anopheline species.

Conclusion

The results of this study have provided data that will help in the correct identification of Anopheles species. It is possible to distinguish among the vectors An. cruzii, An. homunculus and An. bellator based only on female wing characters.

References

Consoli RAGB, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R: Principais mosquitos de importância sanitária no Brasil. 1994, Fiocruz: Rio de Janeiro: Brasil Press, 97-114.

Marrelli MT, Malafronte RS, Flores-Mendoza C, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Kloetzel JK, Marinotti O: Sequence analysis of the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) of 23 ribosomal DNA in Anopheles oswaldoi (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1999, 36: 679-684.

Tadei WP, Dutary-Thatcher B: Malaria vectors in the Brazilian Amazon: Anopheles of the subgenus Nyssorhynchus. Rev Inst Med Trop. 2000, 42: 87-94. 10.1590/S0036-46652000000200005.

Ramirez CCL, Dessen EMB: Cytogenetic analysis of a natural population of Anopheles cruzii. Rev Bras Gen. 1994, 17: 41-46.

Ferreira SR, Luz N: Malária no estado do Paraná – Aspectos históricos e prognose. Acta Biol Par. 2003, 32: 129-156.

Arruda M, Carvalho MB, Nussenzweig RS, Maracic M, Ferreira AW, Cochrane AH: Potential vectores of malaria and their different susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in northern Brazil identified by immunoassay. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1986, 35: 873-881.

Forattini OP: Culicidologia Médica. 2002, São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo Press

Rezende HR, Junior CC, dos Santos CB: Aspectos atuais da distribuição demográfica de Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii Dyar & Knab (1908) no Estado do Espírito Santo, Brasil. Entomologia y Vectores. 2005, 12: 123-126. 10.1590/S0328-03812005000100011.

Sallum MAM, Urbinatti PR, Malafronte RS, Resende HR, Cerutti-Junior C, Natal D: Primeiro registro de Anopheles (Kerteszia) homunculus Komp (Diptera, Culicidae) no Estado do Espírito Santo, Brasil. Rev Bras Entomol. 2008, 52: 671-673. 10.1590/S0085-56262008000400021.

Harrison BA, Ruiz-Lopez F, Falero GC, Savage HM, Pecor JE, Wilkerson RC: Anopheles (Kerteszia) lepidotus (Diptera: Culicidae), not the malaria vector we thought it was: Revised male and female morphology; larva, pupa and male genitalia characters; and molecular verification. Zootaxa. 2012, 3228: 1-17.

Martins CM: Do diagnóstico diferencial específico entre o Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii e o Anopheles (Kerteszia) homunculus pelos caracteres dos adultos fêmeas (Diptera, Culicidae). Rev Bras Malario e D Trop. 1958, 10: 429-430.

Lima MM: Do diagnóstico diferencial entre o Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii e o Anopheles (Kerteszia) homunculus na fase larvária. Rev Bras Malario e D Trop. 1952, 4: 401-411.

Calado DC, Navarro-Silva MA: Identificação de Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzii Dyar & Knab e Anopheles (Kerteszia) homunculus Komp (Diptera, Culicidae, Anophelinae) através de marcadores moleculares (RAPD e RFLP). Rev Bras Entomol. 2005, 22: 1127-1133.

Jirakanjanakit N, Dujardin JP: Discrimination of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) laboratory lines based on wing geometry. Trop Med Public Health. 2005, 36: 858-861.

Dujardin JP: Morphometrics applied to medical entomology. Infect Genet Evol. 2008, 8: 875-890. 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.011.

Vidal PO, Rocha LS, Peruzin MC: Wing diagnostic characters for mosquitoes Culex quinquefasciatus and Culex nigripalpus (Diptera; Culicidae). Rev Bras Entomol. 2011, 55: 134-137. 10.1590/S0085-56262011000100022.

Dujardin JP, Le Pont F: Geographic variation of metric properties within the neotropical sandflies. Infect Genet Evol. 2004, 4: 353-359. 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.05.001.

Motoki MT, Suesdek L, Bergo ES, Sallum MAM: Wing geometry of Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) in five major Brazilian ecoregions. Infect Genet Evol. 2012, in press

Monteiro LR, Reis SF: Princípios de morfometria geométrica. 1999, Ribeirão Preto: Holos Press, 52-106.

ASQC / AIAG: Fundamental statistical process control reference manual. 1991, Troy: MI: AIAG Press, 103-117.

Arnqvist G, Mårtensson T: Measurement error in geometric morphometrics: empirical strategies to assess and reduce its impact on measure of shape. Acta Zool. 1998, 44: 73-96.

Rohlf FJ: Shape statistics: Procrustes superimpositions and tangent spaces. J Classif. 1999, 16: 197-223. 10.1007/s003579900054.

Colucci E, Sallum MAM: Phylogenetic analysis of the subgenus Kerteszia of Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae: Anophelinae) based on morphological characters. Insect System Evol. 2003, 3: 372-373.

Henry A, Thongsripong P, Fonseca-Gonzalez I, Jaramillo-Ocampo N, Dujardin JP: Wing shape of dengue vectors from around the world. Infect Genet Evol. 2010, 10: 207-214. 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.12.001.

Pittendrigh CS: The Ecotopic Specialization of Anopheles homunculus and Its Relation to Competition with A. bellator. Evolution. 1949, 4: 64-78.

Hernández ML, Abrahan LB, Dujardin JP, Gorla DE, Catalá SS: Phenotypic variability and population structure of Peridomestic Triatoma infestans in rural areas of the Arid Chaco (Western Argentina): spatial influence of Macro- and Microhabitats. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 5: 503-513.

Vidal PO, Carvalho E, Suesdek L: Temporal variation on wing geometry of Aedes albopictus. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012, in press

Wilkerson RC, Peyton EL: Standardized nomenclature for the costal wing spots of the Genus Anopheles and other spotted-wing mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1990, 27: 207-224.

Motoki MT, Wilkerson RC, Sallum MAM: The Anopheles albitarsis complex with the recognition of Anopheles oryzalimnetes Wilkerson and Motoki, n. sp. and Anopheles janconnae Wilkerson and Sallum, n. sp. (Diptera: Culicidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009, 104: 823-850. 10.1590/S0074-02762009000600004.

Bridges CB: The mutant crossveinless in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1920, 6: 0660-663. 10.1073/pnas.6.11.660.

Acknowledgements

This investigation has financial support from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP (Grants no. 2011/20397-7; 2005/53973-0), CAPES (Grant no. 23038.005274/2011-24), and CNPq (BPP no. 301666/2011-3 to MAMS). CL is a master recipient of a CNPq scholarship no. 135207/2011-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they don’t have competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CL, MAMS and LS conceived the study, carried out data analysis and results interpretation. TCM collected data in the field. CL and LS written the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenz, C., Marques, T.C., Sallum, M.A.M. et al. Morphometrical diagnosis of the malaria vectors Anopheles cruzii, An. homunculus and An. bellator. Parasites Vectors 5, 257 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-257

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-257