Abstract

Background

This study is an analysis of the prevalence of polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) in epidemiological surveys of salivary tumors published in the English language from 1992 to 2012.

Methods

These surveys included studies from different researchers, countries and continents. The 57 surveys for which it was possible to calculate the percentage of PLGAs among all malignant minor salivary gland tumors (MMSGT) were included in this review.

Results

The statistical analyses show significant differences in the PLGA percentage by time period, country and continent in the studies included in this review. The percentage of PLGAs among MMSGTs varied among the studies, ranging from 0.0% to 46.8%. PLGA rates have varied over the period studied and have most recently increased. The frequency of reported PLGA cases also varied from 0.0% to 24.8% by the country in which the MMSGT studies were performed. The PLGA percentages also varied significantly by continent, with frequencies ranging from 3.9% in Asia to 20.0% in Oceania

Conclusion

Based on these results, we concluded that although the accuracy of PLGA diagnoses has improved, they remain a challenge for pathologists. To facilitate PLGA diagnoses, we have therefore made some suggestions for pathologists regarding tumors composed of single-layer strands of cells that form all of the histological patterns present in the tumor, consistency of the cytological appearance and uniformly positive CK7, vimentin and S100 immunohistochemistry, which indicate a single PLGA phenotype.

Virtual slide

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here:http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/1059098656858324

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) is a malignant epithelial tumor characterized by cytological uniformity, morphological diversity, an infiltrative growth pattern and low metastatic potential[1]. This tumor was recognized as a distinct entity in 1983 by Freedman and Lumerman and Batsakis et al., and it was named polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma by Evans and Batsakis in 1984[2–4].

Clinically PLGA presents as an indolent asymptomatic swelling but occasionally can be painful and even ulcerate. The most common location of PLGA is the palate, although other locations have been described. It occurs more frequently in women affecting mainly the sixth and seventh decade of life. For more details on clinical presentation, prognosis and treatment, we recommend the reviews by Pogodzinski et al., and Paleri, Robinson and Bradley[5, 6]. In general these authors indicate a low grade malignancy and good prognosis of this tumor They also recommend a very careful and systematic follow- up,since recurrences and rare metastases can occur many years after the surgery.

The tumor is characterized by single-layer strands of cells that can form lobular, tubular, cribriform, trabecular, papillary-cystic and cystic histological patterns, which can be illustrated by the presence of extracellular matrix between the strands of cells identified in lobular or solid patterns[7].

Most PLGA cells are cytologically uniform and range from small to medium in size, with vesicular oval nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. Their cytoplasm is ample and exhibits a variable appearance, including eosinophilic, basophilic and clear aspects. The cells have indistinct outlines that lend a syncytial pattern to the active cellular mass. Groups of cells with a coarsely eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, mimicking oncocytes, are occasionally observed, as are mucous cells[1, 8].

The cells show a unique electron microscopy and immunohistochemical phenotype. All cells have microvilli apically and are attached to the basal lamina. The cells are positive for vimentin, CK 7 and S100, a pattern only shared by the mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, as recently described by Skalova et al. and rarely by focal plasmacytoid cells in pleomorphic adenoma[8–10]. A regular distribution of positive staining for β1, β2 and β3 integrins and striking bipolar staining in all of the neoplastic cells reinforces this unique phenotype[11].

Single cells, usually infiltrating surrounding structures, and clear cells in nests are also observed in the lobular PLGA subtype. The stroma appears either strongly eosinophilic and hyalinized, or muco-hyalinized with a bluish tint. Foci of residual salivary gland acini surrounded by neoplastic cells are occasionally found. Peri-neural invasion by groups of tumor cells is a frequent finding, and psammoma-like structures are occasionally observed. This tumor frequently presents with prominent vascularity[8].

Despite greater understanding of this tumor, PLGA remains a diagnostic challenge for pathologists. This conclusion is based on the variability of the epidemiological results obtained by several groups who have studied this tumor.

We have reviewed the epidemiological studies in an attempt to analyse the proportion of PLGAs in salivary gland tumors.

Materials and methods

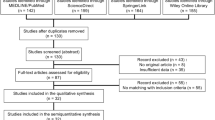

This analysis included 57 epidemiological studies of salivary gland tumors published in the English language from 1992 to 2012. The year 1992 marked the inclusion of PLGA in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of salivary gland tumors[12]. Studies were included in the analysis if they contained the data needed to calculate the fraction of PLGAs in the malignant minor salivary gland tumor (MMSGT) total.

The studies addressing only major salivary gland tumors were excluded because the few cases published on that topic do not significantly contribute to the understanding of PLGA; similarly, studies that included only children and adolescents were excluded from this analysis.

When data were available, we extracted the following information: total number of salivary gland tumors; number of minor salivary gland tumors and their fraction of the total number of tumors; number of MMSGTs and their fraction of the total number of minor salivary gland tumors; number of PLGAs and their fraction of the total number of MMSGTs; and the total number of minor salivary gland tumors.

In this study, we analyzed the fraction of PLGAs in the total number of MMSGTs. It was not possible to obtain the absolute or relative frequencies of malignant salivary tumors, either among minor salivary tumors alone or among major and minor tumors, from studies that reported only MMSGTs.

Statistical analysis

Data were tabulated and descriptive statistics were calculated using frequency tables. G tests were used to ascertain whether the PLGA fraction of all MMSGTs varied by the year, country and continent in which the studies were performed. We would like to emphasize that at no point was it presumed that these studies reflect the prevalence of this tumor with respect to the aforementioned variables (year, country and continent). The significance level was set at 5%. The statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS 20 software package (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Fifty-seven surveys of salivary gland tumors were included in this review (Table 1)[13–68]. From 26,960 cases of salivary gland tumors, 431 (1,6%) were accepted by the authors as been PLGAs.

There has been a significant increase (p < 0.0001 for the G test) in the fraction of PLGA cases reported in the literature since 2007, as shown in Table 2. Epidemiological studies from 1992 to 1994 and 2001 to 2003 included no reports of PLGAs, whilst 1.8% of the MMSGTs reported from 1998 to 2000 were PLGAs. Higher percentages were noted from 1995 to 1997 and 2007 to 2012. The highest PLGA percentages were reported in the studies published from 2004 to 2006 (Table 2).

The frequency of PLGA also varied significantly (p < 0.0001 for the G test) by country, as shown in Table 3. Of the 431 PLGA cases included in this review (Table 1), 95 (22.0%) were from studies performed in the USA, 83 (19.3%) were from Chinese studies and 66 (15.3%) were from Danish studies. The percentage of PLGAs among MMSGTs varied among the studies, ranging from 0.0% to 24.8% (Table 3).

The frequency of reported PLGA cases also varied significantly (p < 0.0001) by the continent in which the MMSGT studies were performed. The continent with the highest reported frequency of PLGAs was Asia, with 3,702 of the 6,891 reported cases (53.7%), followed by America (24.2%) and Europe (19.1%), as shown in Table 4. The PLGA percentages also varied significantly by continent, with frequencies ranging from 3.9% in Asia to 20.0% in Oceania.

Discussion

Analysis of the data from 57 epidemiological studies reflects a variety of methodologies, some examined all (major and minor) salivary gland tumors, while others examined only tumors of the minor glands but included benign and malignant tumors or even MMSGTs alone. This variability most likely reflects differences between the institutions from where most of the data were collected, such as hospitals and medical or dental schools. In other words, it does not reflect the real epidemiology of this tumor in these countries or continents, since they are a few isolated reports.

Nevertheless, it was possible to discern the PLGA percentages among the MMSGT cases, which was the aim of this study. We observed that PLGA rates have varied over the period studied and have most recently increased, most likely due to improved PLGA diagnostic accuracy. Over the last two study periods, the PLGA fraction has stabilized at a value that probably reflects a more accurate percentage of PLGAs among MMSGTs.

We also noted that the percentage varied by the continent where the studies were performed and by individual authors. Based on these results, we suggest that geographical differences alone cannot account for the varying incidence rates, such as occurs with Warthin tumor, which has a lower incidence in Africa, and with the lymphoepithelial carcinoma that has an evident predilection for Inuits (Eskimo), Chinese and Japanese[33, 37, 69, 70]. Also based on these differences it is impossible to extracting other important data as the differences in ACC survival rates between Chinese and occidental data as recently demonstrated by Zhou et al.[71].

Despite our improved understanding of this entity over time, worldwide differences found amongst the studies indicate that diagnosing PLGA remains challenging, probably because histological and cytological criteria are not uniformly applied. Interestingly, this diagnosis does not appear in some of the series, which used the designation “adenocarcinoma” with no further definition, which raises the question of whether a tumor is actually an adenocarcinoma NOS, a PLGA or another entity.

Since the 1990s, many studies have attempted to develop a useful marker for PLGA or to differentiate it from other histologically similar tumors[72–75]. To date there has been no reliable molecular marker to distinguish PLGA from other MMSGTs[76]. The major research focus is currently on finding immunohistochemical differences between PLGA and adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), mainly in the cribriform histology, common to both tumors, which has been tirelessly attempted[77–87].

Controversy on this subject persists in the literature. Some authors believe that immunohistochemistry does not have any proven diagnostic value for identifying PLGA[6, 78, 88, 89]. However, we do not share this opinion as we have successfully used immunohistochemistry in difficult cases or to confirm a histological diagnosis.

For diagnostic purposes, it is essential to characterize the morphology of the cell, the diversity of the histological tumor patterns and to recall that the PLGA cellular population exhibits a constant cytological appearance, despite a variety of growth patterns.

In our experience it is important to note that tumor cytology and histology are usually sufficient for a final diagnosis. However, immunohistochemistry is valuable in unclear PLGA cases, however. Uniformly positive vimentin and CK 7 staining, except for the rare two-layer ducts, is sufficient for a final PLGA diagnosis (Figure 1). S100 is also positive in almost all of the cells, but this characteristic is only diagnostically supportive. When examining cytoskeleton filaments in salivary gland tumors, it is also important to observe which cells are positive for each protein, rather than simply indicating the percentage of tumors in a series that are positive for each marker. Using this information, the immunohistochemistry of the cytoskeleton filament contributes greatly to the diagnosis of salivary gland tumors, especially PLGAs.

References

Luna MA, Wenig BM: Polymorhpous low grade adenocarcinoma. World health organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Edited by: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. 2005, Lyon: IARC Press, 223-224. 1

Evans HL, Batsakis JG: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. A study of 14 cases of a distinctive neoplasm. Cancer. 1984, 53 (4): 935-942. 10.1002/1097-0142(19840215)53:4<935::AID-CNCR2820530420>3.0.CO;2-V.

Freedman PD, Lumerman H: Lobular carcinoma of intraoral minor salivary gland origin. Report of twelve cases. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1983, 56 (2): 157-166. 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90282-7.

Batsakis JG, Pinkston GR, Luna MA, Byers RM, Sciubba JJ, Tillery GW: Adenocarcinomas of the oral cavity: a clinicopathologic study of terminal duct carcinomas. J Laryngol Otol. 1983, 97 (9): 825-835. 10.1017/S0022215100095062.

Pogodzinski MS, Sabri AN, Lewis JE, Olsen KD: Retrospective study and review of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2006, 116 (12): 2145-2149. 10.1097/01.mlg.0000243200.35033.2b.

Paleri V, Robinson M, Bradley P: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008, 16 (2): 163-169. 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282f70441.

Raitz R, Martins MD, Araujo VC: A study of the extracellular matrix in salivary gland tumors. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003, 32 (5): 290-296. 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00019.x.

Araujo V, Sousa S, Jaeger M, et al.: Characterization of the cellular component of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Oral oncol. 1999, 35 (2): 164-172. 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00102-X.

Gonzalez-Garcia R, Rodriguez-Campo FJ, Munoz-Guerra MF, et al.: Polymorphous lowgrade adenocarcinoma of the palate: report of cases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005, 32 (3): 275-280. 10.1016/j.anl.2005.03.019.

Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, et al.: Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010, 34 (5): 599-608.

Araujo VC, Loducca SV, Sousa SO, Williams DM, Araujo NS: The cribriform features of adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: cytokeratin and integrin expression. Ann Diag Pathol. 2001, 5 (6): 330-334. 10.1053/adpa.2001.29339.

Seifert G, Sobin LH: World health classification of tumors. Histological typing of salivary gland tumours. 1991, Berlin: Springer, 2

Onyango JF, Awange DO, Muthamia JM, Muga BI: Salivary gland tumours in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1992, 69 (9): 525-530.

Rippin JW, Potts AJ: Intra-oral salivary gland tumours in the west midlands. Br Dent J. 1992, 173 (1): 17-19. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807925.

Loyola AM, de Araujo VC, de Sousa SO, de Araujo NS: Minor salivary gland tumours. A retrospective study of 164 cases in a Brazilian population. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995, 31B (3): 197-201.

Neely MM, Rohrer MD, Young SK: Tumors of minor salivary glands and the analysis of 106 cases. J Okla Dent Assoc. 1996, 86 (4): 50-52.

Rivera-Bastidas H, Ocanto RA, Acevedo AM: Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors: a retrospective study of 62 cases in a Venezuelan population. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996, 25 (1): 1-4. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01214.x.

Rushing T, Strohm SS, Christie DW, Krolls SO: Salivary gland tumors in Mississippi. Miss Dent Assoc J. 1996, 52 (3): 33-35.

Jones AV, Craig GT, Speight PM, Franklin CD: The range and demographics of salivary gland tumours diagnosed in a UK population. Oral oncol. 2008, 44 (4): 407-417. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.05.010.

Kusama K, Iwanari S, Aisaki K, et al.: Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors: a retrospective study of 129 cases. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1997, 39 (3): 128-132. 10.2334/josnusd1959.39.128.

Nagler RM, Laufer D: Tumors of the major and minor salivary glands: review of 25 years of experience. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17 (1B): 701-707.

Lopes MA, Kowalski LP, da Cunha Santos G, Paes de Almeida O: A clinicopathologic study of 196 intraoral minor salivary gland tumours. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999, 28 (6): 264-267.

Maaita JK, Nabih A, Al-Tamimi S, Wraikat A: Salivary gland tumors in Jordan: a retrospective study of 221 patients. Croat Med J. 1999, 40 (3): 539-542.

Pacheco-Ojeda L, Domeisen H, Narvaez M, Tixi R, Vivar N: Malignant salivary gland tumors in quito, ecuador. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2000, 62 (6): 296-302. 10.1159/000027772.

Koivunen P, Suutala L, Schorsch I, Jokinen K, Alho O-P: Malignant epithelial salivary gland tumors in northern Finland: incidence and clinical characteristics. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002, 259 (3): 146-149. 10.1007/s00405-001-0435-9.

Vargas PA, Gerhard R, Araujo Filho VJF, de Castro IV: Salivary gland tumors in a Brazilian population: a retrospective study of 124 cases. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2002, 57 (6): 271-276.

Masanja MI, Kalyanyama BM, Simon ENM: Salivary gland tumours in Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 2003, 80 (8): 429-434.

Hyam DM, Veness MJ, Morgan GJ: Minor salivary gland carcinoma involving the oral cavity or oropharynx. Aust Dent J. 2004, 49 (1): 16-19. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00044.x.

Kokemueller H, Swennen G, Brueggemann N, Brachvogel P, Eckardt A, Hausamem JE: Epithelial malignancies of the salivary glands: clinical experience of a single institution-a review. I Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004, 33 (5): 423-432. 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.02.007.

Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J, Weerapradist W: A retrospective study of 60 cases of salivary gland tumors in a Thai population. Quintessence Int Berlin, Germany. 1985, 35 (7): 577-581.

Strick MJ, Kelly C, Soames JV, McLean NR: Malignant tumours of the minor salivary glands–a 20 year review. Br J Plastic Surg. 2004, 57 (7): 624-631. 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.017.

Toida M, Shimokawa K, Makita H, et al.: Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors: a clinicopathological study of 82 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 34 (5): 528-532. 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.10.010.

Vuhahula EAM: Salivary gland tumors in Uganda: clinical pathological study. Afr Health Sci. 2004, 4 (1): 15-23.

Lima SS, Soares AF, de Amorim RFB, Freitas RDA: Epidemiologic profile of salivary gland neoplasms: analysis of 245 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005, 71 (3): 335-340.

Ito F, Ito K, Vargas P, de Almeida OP, Lopes M: Salivary gland tumors in a Brazilian population: a retrospective study of 496 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 34 (5): 533-536. 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.02.005.

Luukkaa H, Klemi P, Leivo I, et al.: Salivary gland cancer in Finland 1991–96: an evaluation of 237 cases. Acta Oto Laryngol. 2005, 125 (2): 207-214. 10.1080/00016480510003174.

Otoh EC, Johnson NW, Olasoji H, Danfillo IS, Adeleke OA: Salivary gland neoplasms in Maiduguri, north-eastern Nigeria. Oral Dis. 2005, 11 (6): 386-391. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01137.x.

Yih W-Y, Kratochvil FJ, Stewart JCB: Intraoral minor salivary gland neoplasms: review of 213 cases. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2005, 63 (6): 805-810. 10.1016/j.joms.2005.02.021.

Ascani G, Pieramici T, Messi M, Lupi E, Rubini C, Balercia P: Salivary glands tumours: a retrospective study of 454 patients. Minerva Stomatol. 2006, 55 (4): 209-214.

Ansari MH: Salivary gland tumors in an Iranian population: a retrospective study of 130 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65 (11): 2187-2194. 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.025.

Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM: Relative frequency of intra-oral minor salivary gland tumors: a study of 380 cases from northern California and comparison to reports from other parts of the world. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007, 36 (4): 207-214. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00522.x.

Jones AS, Beasley NJ, Houghton DJ, Helliwell TR, Husband DJ: Tumours of the minor salivary glands. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1998, 23 (1): 27-33. 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00088.x.

Ladeinde AL, Adeyemo WL, Ogunlewe MO, Ajayi OF, Omitola OG: Salivary gland tumours: a 15-year review at the dental centre Lagos university teaching hospital. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2007, 36 (4): 299-304.

Pires FR, Pringle GA, de Almeida OP, Chen S-Y: Intra-oral minor salivary gland tumors: a clinicopathological study of 546 cases. Oral oncol. 2007, 43 (5): 463-470. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.04.008.

Wang D, Li Y, He H, et al.: Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors in a Chinese population: a retrospective study on 737 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007, 104 (1): 94-100. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.012.

Copelli C, Bianchi B, Ferrari S, Ferri A, Sesenna E: Malignant tumors of intraoral minor salivary glands. Oral oncol. 2008, 44 (7): 658-663. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.08.018.

Li L-J, Li Y, Wen Y-M, Liu H, Zhao H-W: Clinical analysis of salivary gland tumor cases in west china in past 50 years. Oral oncol. 2008, 44 (2): 187-192. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.01.016.

Rahman B, Mamoon N, Jamal S, et al.: Malignant tumors of the minor salivary glands in northern Pakistan: a clinicopathological study. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2008, 1 (2): 90-93.

Subhashraj K: Salivary gland tumors: a single institution experience in India. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008, 46 (8): 635-638. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.020.

Chijiwa H, Sakamoto K, Umeno H, Nakashima T, Suzuki G, Hayafuchi N: Minor salivary gland carcinomas of oral cavity and oropharynx. J Laryngol Otol Suppl. 2009, 123 Suppl: 52-57.

Dhanuthai K, Boonadulyarat M, Jaengjongdee T, Jiruedee K: A clinico-pathologic study of 311 intra-oral salivary gland tumors in Thais. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009, 38 (6): 495-500. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00791.x.

Gao N, Li Y, Li L-J, Wen Y-M: Clinical analysis of head and neck cancer cases in southwest china 1953–2002. J Int Med Res. 2009, 37 (1): 189-197.

Mucke T, Robitzky LK, Kesting MR, et al.: Advanced malignant minor salivary glands tumors of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009, 108 (1): 81-89. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.01.013.

Ochicha O, Malami S, Mohammed A, Atanda A: A histopathologic study of salivary gland tumors in Kano, northern Nigeria. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009, 52 (4): 473-476. 10.4103/0377-4929.56121.

de Oliveira F, Duarte E, Taveira C: Salivary gland tumor: a review of 599 cases in a Brazilian population. Head Neck. 2009, 3 (4): 271-275. 10.1007/s12105-009-0139-9.

Targa-Stramandinoli R, Torres-Pereira C, Piazzetta CM, Giovanini AF, Amenabar JM: Minor salivary gland tumours: a 10-year study. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2009, 60 (3): 199-201. 10.1016/S0001-6519(09)71231-2.

Tilakaratne WM, Jayasooriya PR, Tennakoon TMPB, Saku T: Epithelial salivary tumors in Sri Lanka: a retrospective study of 713 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009, 108 (1): 90-98. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.01.026.

Erovic BM, Schopper C, Pammer J, et al.: Multimodal treatment of patients with minor salivary gland cancer in the case of recurrent disease. Head Neck. 2010, 32 (9): 1167-1172. 10.1002/hed.21312.

Carrillo JF, Maldonado F, Carrillo LC, et al.: Prognostic factors in patients with minor salivary gland carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Head Neck. 2011, 33 (10): 1406-1412. 10.1002/hed.21641.

Kakarala K, Bhattacharyya N: Survival in oral cavity minor salivary gland carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010, 143 (1): 122-126.

Kruse ALD, Gratz KW, Obwegeser JA, Lubbers H-T: Malignant minor salivary gland tumors: a retrospective study of 27 cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010, 14 (4): 203-209. 10.1007/s10006-010-0217-x.

Tian Z, Li L, Wang L, Hu Y, Li J: Salivary gland neoplasms in oral and maxillofacial regions: a 23-year retrospective study of 6982 cases in an eastern Chinese population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010, 39 (3): 235-242. 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.10.016.

Bjorndal K, Krogdahl A, Therkildsen MH, et al.: Salivary gland carcinoma in Denmark 1990–2005: a national study of incidence, site and histology. Results of the Danish head and neck cancer group (DAHANCA). Oral oncol. 2011, 47 (7): 677-682. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.04.020.

Morais M, Azevedo P, Carvalho C, Medeiros L, Lajus T, Costa ALL: Clinicopathological study of salivary gland tumors: an assessment of 303 patients. Cad Saude Publica. 2011, 27 (5): 1035-1040. 10.1590/S0102-311X2011000500020.

Schwarz S, Muller M, Ettl T, Stockmann P, Zenk J, Agaimy A: Morphological heterogeneity of oral salivary gland carcinomas: a clinicopathologic study of 41 cases with long term follow-up emphasizing the overlapping spectrum of adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous lowgrade adenocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011, 4 (4): 336-348.

Venkata V, Irulandy P: The frequency and distribution pattern of minor salivary gland tumors in a government dental teaching hospital, Chennai, India. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011, 111 (1): e32-e39. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.019.

Bello IO, Salo T, Dayan D, et al.: Epithelial salivary gland tumors in Two distant geographical locations, Finland (Helsinki and Oulu) and Israel (Tel Aviv): a 10-year retrospective comparative study of 2,218 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6 (2): 224-231. 10.1007/s12105-011-0316-5.

Lukšić I, Virag M, Manojlović S, Macan D: Salivary gland tumours: 25 years of experience from a single institution in Croatia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012, 40 (3): e75-81. 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.05.002.

Tsang WYW, Kuo TT, Chan JKC: Lymphoepithelial carcinoma. World health organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Edited by: Barnes LE, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. 2005, Lyon: IARC Press, 251-152. 1

Simpson RHW, Eveson JW: Wharthin tumour. World health organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Edited by: Barnes LE, Evenson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. 2005, Lyon: IARC Press, 263-265. 1

Quan Z, Hong C, Hongkai Z, Yiding H, Honggang L: Increased numbers of P63-positive/CD117-positive cells in advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma give a poorer prognosis. Diagn Pathol. 2012, 7: 119-10.1186/1746-1596-7-119.

Gnepp DR, el-Mofty S: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: glial fibrillary acidic protein staining in the differential diagnosis with cellular mixed tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997, 83 (6): 691-5. 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90321-8.

Furuse C, Tucci R, Machado de Sousa SO, Rodarte Carvalho Y, Cavalcanti de Araujo V: Comparative immunoprofile of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and canalicular adenoma. Ann Diag Pathol. 2003, 7 (5): 278-80. 10.1016/S1092-9134(03)00084-4.

Westernoff TH, Jordan RCK, Regezi JA, Ramos DM, Schmidt BL: Beta-6 integrin, tenascin- C, and MMP-1 expression in salivary gland neoplasms. Oral oncol. 2005, 41 (2): 170-4. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.08.002.

Taufik D, Hussein MR: Juvenile pleomorphic adenoma of the cheek: a case report and review of literature. Diagn Pathol. 2009, 4: 32-10.1186/1746-1596-4-32.

Persson F, Fehr A, Sundelin K, Schulte B, Löning T, Stenman G: Studies of genomic imbalances and the MYB-NFIB gene fusion in polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Oncol. 2012, 40 (1): 80-4.

Loducca SV, Raitz R, Araujo NS, Araujo VC: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma: distinct architectural composition revealed by collagen IV, laminin and their integrin ligands (alpha2beta1 and alpha3beta1). Histopathology. 2000, 37 (2): 118-23. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00900.x.

Darling MR, Schneider JW, Phillips VM: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma: a review and comparison of immunohistochemical markers. Oral oncol. 2002, 38 (7): 641-5. 10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00003-9.

Edwards PC, Bhuiya T, Kelsch RD: C-kit expression in the salivary gland neoplasms adenoid cystic carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, and monomorphic adenoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003, 95 (5): 586-93. 10.1067/moe.2003.31.

Epivatianos A, Iordanides S, Zaraboukas T, Antoniades D: Adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands: a comparative immunohistochemical study using the epithelial membrane and carcinoembryonic antibodies. Oral Dis. 2005, 11 (3): 175-80. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01110.x.

Beltran D, Faquin WC, Gallagher G, August M: Selective immunohistochemical comparison of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006, 64 (3): 415-23. 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.027.

Woo VL, Bhuiya T, Kelsch R: Assessment of CD43 expression in adenoid cystic carcinomas, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas, and monomorphic adenomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006, 102 (4): 495-500. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.038.

Epivatianos A, Poulopoulos A, Dimitrakopoulos I, et al.: Application of alpha-smooth muscle actin and c-kit in the differential diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma from polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma. Oral oncol. 2007, 43 (1): 67-76. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.01.004.

Prasad ML, Barbacioru CC, Rawal YB, Husein O, Wen P: Hierarchical cluster analysis of myoepithelial/basal cell markers in adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008, 21 (2): 105-14.

Ferrazzo KL, Neto MM, dos Santos E, dos Santos PD, de Sousa SOM: Differential expression of galectin-3, beta-catenin, and cyclin D1 in adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009, 38 (9): 701-7. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00776.x.

Shaimaa Ghazy E, Iman Helmy M, Houry Baghdadi M: Maspin and MCM2 immuno profiling in salivary gland carcinomas. Diagn Pathol. 2011, 6: 89-10.1186/1746-1596-6-89.

Saghravanian N, Mohtasham N, Jafarzadeh H: Comparison of immunohistochemical markers between adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. J Oral Sci. 2009, 51 (4): 509-14. 10.2334/josnusd.51.509.

Gupta R, Gupta K, Gupta R: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the tongue: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009, 3: 9313-10.1186/1752-1947-3-9313.

Simpson RH, Clarke TJ, Sarsfield PT, Gluckman PG, Babajews AV: Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands: a clinicopathological comparison with adenoid cystic carcinoma. Histopathology. 1991, 19 (2): 121-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00002.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VCA responsible for the conception and designed of research and wrote the most part of the manuscript. FPS and ABS responsible for collecting data. CT responsible for statistical analysis. NSA reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Araujo, V.C., Passador-Santos, F., Turssi, C. et al. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: an analysis of epidemiological studies and hints for pathologists. Diagn Pathol 8, 6 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-6