Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and different HCV genotypes show characteristic variations in their pathological properties. Insulin resistance (IR) occurs early in HCV infection and may synergize with viral hepatitis in HCC development. Egypt has the highest reported rates of HCV infection (predominantly genotype 4) in the world; this study investigated effects of HCV genotype-4 (HCV-4) on prevalence of insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C (CHC) and HCC in Egyptian patients.

Methods

Fifty CHC patients, 50 HCC patients and 20 normal subjects were studied. IR was estimated using HOMA-IR index and HCV-4 load determined using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Hepatitis B virus was excluded by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Standard laboratory and histopathological investigations were undertaken to characterize liver function and for grading and staging of CHC; HCC staging was undertaken using intraoperative samples.

Results

HCC patients showed higher IR frequency but without significant difference from CHC (52% vs 40%, p = 0.23). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed HOMA-IR index and International Normalization Ratio independently associated with fibrosis in CHC; in HCC, HbA1c, cholesterol and bilirubin were independently associated with fibrosis. Fasting insulin and cholesterol levels were independently associated with obesity in both CHC and HCC groups. Moderate and high viral load was associated with high HOMA-IR in CHC and HCC (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

IR is induced by HCV-4 irrespective of severity of liver disease. IR starts early in infection and facilitates progression of hepatic fibrosis and HCC development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persistent Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is widespread; it affects millions of people worldwide and induces a range of chronic liver disease [1]. Chronic HCV infection causes progressive hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in up to 20% of patients and approximately 10%-20% of cirrhotic patients may go on to develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) within five years [2]. HCC is the most frequent cause of death in patients infected with HCV, and epidemiological trends suggest that the mortality rate is rising [3]. Understanding the risk factors for HCC development in patients infected with HCV is thus of great importance for refinement of treatment strategies and healthcare delivery. HCV has a high mutation rate and six major genotypes have been characterized, each with a distinctive geographical distribution and pathological properties [1]. Egypt has the highest countrywide prevalence of HCV in the world; about 12 to 15% of the total population are infected [4], with HCV Genotype-4 (HCV-4) accounting for the overwhelming majority of HCV infections.

HCV has been identified as a cause of metabolic syndrome, a complex that includes dyslipidemia, diabetes and insulin resistance (IR). IR is a key feature of this syndrome and a variety of potential molecular pathways by which HCV may contribute to IR have been suggested [5]. Patients infected with HCV have significantly higher IR than healthy controls matched for age, sex and body mass index [6].

Recent studies have found that HCV-associated IR may cause; (i) hepatic steatosis, (ii) resistance to anti-viral treatment, (iii) hepatic fibrosis and esophageal varices, (iv) hepatocarcinogenesis and proliferation of HCC and (v) extrahepatic manifestations [7, 8]. IR has emerged as a risk factor for a wide variety of cancers, including endometrial and breast (especially after menopause), colon, and rectal, esophageal, kidney, pancreatic, biliary, ovarian and cervical cancers [9]. In chronic HCV infection, IR can favor fibrosis progression directly and act indirectly by inducing steatosis in a genotype-dependent manner [10].

It has been reported that IR can increase the risk of developing HCC in patients with chronic HCV infection [11]. A multiplicity of viral and host factors may play a crucial role in facilitating the onset of IR in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) that may ultimately end with HCC development [5]. Given high levels of endemic CHC infection in Egypt, and that IR is a potentially modifiable factor, a better understanding of correlations of IR with HCC among Egyptian patients infected with HCV-4 is urgently needed.

The focus of the study was to investigate: (i) the prevalence of IR among CHC and HCC patients and its possible role in HCC development in the context of high prevalence of HCV-4 infection and (ii) impact of other factors such as host characteristics (age, gender, etc.), viral parameters (viral load, viral genotype), and other variables including obesity and dyslipidemia on IR and hepatic carcinogenesis.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This prospective study was conducted with 120 participants divided into three groups. The first group comprised 50 patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype- 4 (CHC). The second group comprised 50 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients diagnosed and treated at Ain Shams University Specialized Hospital, Cairo, between February 2009 and February, 2010. A third group included 20 apparently healthy participants who had donated blood at the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University.

The Ethical Committee of Ain Shams University Specialized Hospital approved the study protocol, which was prepared in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and later revisions. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment in the study and all were mentally and physically capable of answering a questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria: adult patients of both sexes (20-70 years old), diagnosis within the previous 6 months, positive for HCV RNA in serum (by RT-PCR assay), with evidence of chronic hepatitis supported by liver biopsy. The control group was made from adults negative for HCV RNA. Patients were not receiving hepatitis treatment at the time of sampling.

The presence of HBV infection or co-infection was excluded by serum ELISA for anti-HBc and HBsAg. In addition to investigations needed to fulfill the selection criteria, all individuals included in this study were subjected to the following:

A. Medical History

Full history was taken with special reference to risk factors for liver diseases such as previous HCV exposure in surgical wards, blood transfusions, dental therapy, needlestick injury, history of HCV in the spouse and i.v. injection.

B. Physical Examination

Complete medical examination with particular focus upon the manifestations of hepatitis such as jaundice, hepatomegaly, and tenderness in the right hypochondrium. BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Abdominal ultrasonography was performed for all patients.

C. Histopathological investigations

Liver biopsy specimens were formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded then sectioned and stained (hematoxylin and eosin) for routine histopathological examination. Grading and staging of chronic hepatitis was performed according to Modified Knodell's Score [12]. Liver tissues from HCC cases were collected intraoperatively. These samples were graded using World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria [13] and staging was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer [13].

D. Laboratory investigations

Venous blood samples were taken in the morning after 12-h overnight fast. Plasma glucose, HbA1c, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gammaglutamyl transferase (GGT), albumin (Alb), total bilirubin levels (Bil), cholesterol (Chol), and triglycerides (TG) were measured by using Synchron CX4 clinical system (standard clinical laboratory methods) at the Clinical Laboratory Department, Ain Shams Specialized Hospital. Serum insulin levels and α-fetoprotein levels were estimated by serological techniques (Axyam System, Abbott Laboratories).

Platelet count (Plt) and Prothrombin Time (PT) measurements were performed for all patients; normal PT was 12 seconds (100% concentration and International Normalization Ratio (INR) of 1).

Insulin resistance (IR) was calculated on the basis of fasting levels of plasma glucose and serum insulin, according to the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) method. Calculation for the HOMA model followed a standard protocol; insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) = fasting glucose (mg/dL) × fasting insulin (μIU/mL)/405 [14]. The HOMA-IR index has seen widespread use, with various cut-off values for insulin resistance. In many studies of Caucasian populations a cut-off value of 2.5 has been applied; other studies have used higher cut-off values, for example 3.0 [15]. Genetic variation with respect to different ethnic groups will influence choice of cut-off value (discussed by Esteghamati [16]); for this study we used a cut-off value of 4.0 [17].

E. Viral Markers

ELISA assays

Sera of all patients and controls were tested for HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HCV antibodies by ELISA, using third generation kits (DiaSorin, Italy) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for hepatitis C virus

RT-PCR was performed as previously described [18] and 10 μl samples of the amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis (1.2% agarose gel, ethidium bromide staining).

HCV genotyping

HCV genotype was determined using INNO-LiPAII and III versant Kit (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) according to manufacturer's directions

Quantitation of HCV-RNA in serum

HCV-RNA was quantitated in all patients' serum samples using Real Time PCR (RT-PCR) [15] (primers and RT-PCR reagents from Stratagene, Qiagen, USA). Low viremia was defined as viral load lower than 100 x103 IU/L, moderate viremia as viral load 100-1000 × 103 IU/L, and high viremia when viral load > 1000 x103 IU/L [19].

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSSwin statistical package version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Chi-square test (Fisher's exact test) was used to examine relationships between qualitative variables. For quantitative data, comparison between two groups was undertaken using Mann-Whitney test and comparison between 3 groups with ANOVA test or Kruskal-Wallis test followed post-Hoc "Schefe test". Spearman-rho method was used to test correlation between numerical variables. Multivariate analysis was performed using multiple linear regression model using forward method for the significant factors affecting fibrosis on univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis (logistic regression) was performed to find the predictors for HCC development All tests are two-tailed; a p-value<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

(Table 1): Ages of CHC patients (median 57 years; range 34-70 yrs) and HCC patients (median 60 years; range 35-76 yrs) were closely comparable, while control group participants were younger (median 35 years; range 19-57). Preponderance of males was observed with both CHC and HCC groups; 1:1.5 and 1:1.6 respectively. There was no significant difference between CHC and HCC patients regarding age or sex (p = 0.14 and 0.838, respectively). No significant difference was observed in BMI distribution between the study groups (p = 0.908).

Biochemical, viral and pathological factors

HCC patients showed significantly higher median values of INR and HbA1c, than CHC patients (p < 0.0001, p = 0.05, respectively), but significantly lower median values for albumin and platelets (p < 0.001). HCC patients also showed significantly higher median values of AST, Bil, GGT and α-fetoprotein when compared to CHC patients (p < 0.001 for all). No significant differences were found between HCC and CHC patients regarding median values of ALT, glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR index values, cholesterol and triglycerides (p = 0.09, = 0.81, = 0.178,= 0.643,= 0.954, = 0.999).

Frequency of high value for HOMA-IR index (>4) and presence of dyslipidemia were not significantly different between CHC and HCC patients (Table 2).

HCC patients showed significantly higher frequency of presentation with moderate viral load than CHC patients (70% vs 42%, p < 0.001) and higher grades of fibrosis (IV and V: 45/50 (90%) for HCC vs 15/50 (30%), for the CHC group (p < 0.001).

The normal control group showed significant difference when compared to the HCC or CHC groups (p < 0.001) for all parameters studied, except BMI.

Factors associated with development of fibrosis

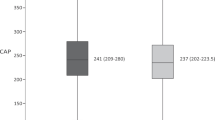

Multiple linear regression analysis showed that HOMA-IR and INR are the only independent predictors of fibrosis in CHC patients after adjustment (of age, AST, total bilirubin, albumin, glucose, α-fetoprotein, platelets, GGT, fasting insulin, HbA1c, cholesterol and triglycerides). In HCC patients, HbA1c, triglycerides and total bilirubin are independent predictors of fibrosis after adjustment (of age, AST, INR, albumin, glucose, α-fetoprotein, platelets, GGT, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR and cholesterol) Table 3. Correlation between HOMA-IR index and grades of fibrosis in CHC and HCC groups are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Viral load and insulin resistance

Analysis of HCV viral load with HOMA-IR showed that in the CHC group, both moderate and high viral load were significantly associated with higher values for HOMA-IR compared to those with lower median viral load (4.19, 5.15 vs 1.85, p < 0.001) Figure 3. Similar differences were not observed in HCC patients.

HCC development

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that fibrosis was the only independent predictor factor for risk of HCC development (OR: 21.64, 95%CI: 1.81-259.09, p = 0.02), after adjustment of (age >56y, HBA1c >7%, AST >40, TBil >1, GGT >50, INR>1) (Table 4).

Obesity

Obesity was significantly associated with higher HOMA-IR index value in both CHC and HCC patients (p < 0.001). Obese patients (CHC and HCC) showed significantly higher frequency of high viral load when compared to non-obese patients (p = 0.001) Figure 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis showed that fasting insulin and cholesterol are independent predictors for obesity among CHC and HCC patients (OR: 1.663, p < 0.001, OR: 1.052, p < 0.001 respectively) (Table 5).

CHC and HCC with high HOMA-IR index

Table 6 shows a comparison of CHC and HCC patients demonstrating HOMA-IR > 4. The strong similarities of these variables suggest that HCV-4, like HCV genotypes 1 and 2, leads to fibrosis rather than the steatosis seen with genotype 3.

Discussion

This study has provided valuable cues with respect to the potential role of insulin resistance in the pathological consequences of infection with HCV genotype 4 in a population notable for high rates of HCV infection and obesity. Previous studies suggest a strong synergistic effect of metabolic factors and viral hepatitis in HCC development in HCV-infected patients [20, 21]. In contrast to a previous report which found association of IR, regardless of diabetes, with development of HCC [11], the present study showed no significant difference in HOMA-IR values, diabetes and insulin levels between CHC and HCC patients. This discrepancy might be due to confounding factors such as:

i) High prevalence of HCV-4 infection; in high prevalence areas the incidence of HCC is heavily influenced by virus-related characteristics that confound other risk factors for HCC, blurring their effect [22]. This may indicate that the effect of IR on the risk of HCC is modified by HCV infection.

ii) High prevalence of obesity among our patients without significant difference between CHC and HCC. It has been documented that obesity is an independent risk factor for IR in HCV and HCC [23].

iii) The number of participants in this study may not have been sufficient to reveal small differences in prevalence in the studied population

In the present study, the frequency of conspicuous insulin resistance (HOMA-IR >4) was 40% among CHC patients. This finding is in agreement with Harrison and co-workers [24], who reported that 30 to 70% of CHC patients display some evidence of IR. These results have suggested the occurrence of IR at early stage(s) of chronic HCV infection irrespective of the severity of liver disease and thus the possible role of IR as a metabolic factor that increases risk of HCC development [25]. It is noteworthy that there are a variety of plausible direct effects of HCV in modulating insulin signaling and molecular pathways involved in IR development in hepatocytes [26, 27]. In turn, hyperinsulinemia that results from IR stimulates growth of HCC and inhibits apoptosis in diabetic patients [10, 25, 28].

It is very likely that a high prevalence of diabetes in our CHC group (96%) may be a risk factor for HCC development [25, 29] but this effect may be confounded by the underlying liver disease [22]. Veldt and co-workers [25] have reported that the 5 year risk of developing HCC is 11.4% for patients with both diabetes mellitus and CHC with advanced fibrosis while patients without diabetes have lower risk of HCC (occurrence of HCC in 5% after 5 years).

Multivariate analysis showed that HOMA-IR values and INR were independently associated with fibrosis in CHC patients, but not in the HCC patient group. This is in accord with our hypothesis that early occurrence of IR may hasten progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis which may culminate in HCC development. This is consistent with recent reports, including a Japanese cohort study [30, 31].

It has been reported that the mean IR index increases with stage of fibrosis and may help in differentiating fibrosis stages [32]. This was observed in our results (Figure 1) where HOMA-IR was significantly associated with high grades of fibrosis in CHC patients (p < 0.001). IR promotes fibrosis progression in the liver of patients with HCV through development of hepatic steatosis, hyperleptinemia, increased TNF production and reduced expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR ץ receptors) [27, 33]. High levels of insulin and glucose could promote fibrogenesis by stimulating release of connective tissue growth factor from hepatic stellate cells [34]. The present study did not investigate steatosis as a possible link between IR and fibrosis.

In our HCC patient group, HbA1c, triglycerides and total bilirubin levels were found to be independently associated with fibrosis. This finding was not observed in previous studies. Furthermore, multivariate analysis showed that fibrosis was the only independent predictor for risk of HCC development after adjustment of age and other markers of advanced liver disease (Plt, Bil, albumin, INR AST, GGT). These results confirm a distinct role of diabetes in HCC development [25]; in tumorigenesis, transformed cells require more glucose [35].

It is well established that IR is associated with abdominal obesity, elevated blood cholesterol and hypertension [36]. In the present study, obesity was found significantly associated with IR (higher HOMA-IR index value) in both CHC and HCC patient groups (p < 0.001 compared to non-obese patients). Obesity may directly lead to a state of chronic inflammation with consequent increases in the expression of signaling molecules, some of which (for example, NFKB, and fibroblast growth factor) are thought to be involved in carcinogenesis [37, 38]. Chen and co-workers [21] have reported that although overweight itself did not appreciably increase risk of HCC, a combination of high BMI and diabetes showed a synergistic effect. Our results confirmed a synergistic effect of obesity when combined with high level of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR index) in risk of HCC development associated with HCV-4 infection.

Multivariate analysis in the present study showed that fasting insulin and cholesterol were independent predictors for obesity. This readily explains the prevalence of obesity among our patients. Type 2 diabetes is a major health problem in the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) region and many studies have established a panel of risk factors associated with IR and type 2 diabetes; family history, body fat distribution, age, gender, smoking and physical activity. Obesity and IR are strong cofactors of HCV-related liver disease and predict lack of response to treatment [39].

Division of patient groups using age of >57 revealed that most of our HCC patients were over 57 years in age and the number in this age group showed significant difference when compared to CHC patients (p = 0.04). In univariate analysis, IR was correlated with age in CHC patients. It has been suggested that age is associated with a decline in mitochondrial function which could contribute to IR [40]. However, this relationship disappeared in multivariate analysis; this indicates that age is one of the confounding factors for development of IR [31].

Our HCC patients showed higher frequency of moderate viral load than patients with CHC infection; a result in accord with that reported by Hsu [33]. Our patients (CHC or HCC) showed that moderate or high viral load was significantly associated with high levels of insulin resistance (high HOMA-IR index) compared to those with low viral load (median 4.19, 4.80 vs 2.24, p < 0.001). Interestingly, on analysis of correlation between viral load and HOMA-IR in our CHC and HCC groups separately, it was apparent that in the CHC patient group, cases with moderate and high viral load were significantly associated with higher HOMA-IR index compared to those with lower viral load (4.19, 5.15 vs 1.85, p < 0.001) while in HCC patients, moderate and high viral loads were not significantly associated with higher HOMA-IR values (median 4.19, 4.67 vs 3.06 p = 0.70 compared to cases with lower viral load). This observation is readily rationalized by a role of HCV infection in production of IR before cirrhosis and HCC development. This supports the hypothesis that a modulating effect of HCV on insulin signaling pathways plays a role in a separate pathway involved in the process of hepatocarcinogenesis [41].

The association of HOMA-IR with viral load is an important finding of the study. The patient with HCV infection can present with IR due to metabolic and to viral factors; the molecular bases of these effects have been subject to intense research scrutiny though the relative importance of some of these interrelated effects to the clinical picture remains to be fully determined. Chronic inflammation as a non-specific consequence of hepatic inflammation due to HCV infection leads to IR associated with metabolic liver disease through increased levels of IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6 and leptin, and reduced levels of adiponectin. This will complement obesity effects which involve simulation of inflammatory mediator IkB kinase β and phosphorylation of IRS-1 [26].

Multiple pathways for direct effects of the virus on IR have been identified. These include impairment of insulin signaling through stimulation of proteosomal inactivation of IRS-1 and IRS-2, viral induction of excess TNF giving enhanced production of suppressor cytokine signal proteins (SOCS) in a genotype specific manner [42] which act on the Akt pathway (also down-regulated by HCV-stimulated PP2A activity) giving impairment of GLUT-4 glucose transporter activation [43]; and action of HCV core protein as an inhibitor of PPAR α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors) [44]. In addition, HCV NS5a protein induces mitochondrial ROS (reactive oxygen species) production of which activate release of a cascade of inflammatory mediators through activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and HCV NS3, and induce endoplasmic reticulum stress signals. Progressive fibrosis induces IR due to impairment in insulin clearance with resulting insulin levels [17, 31].

Conclusions

Insulin resistance may be induced by HCV infection irrespective of the severity of liver disease; insulin resistance starts at an initial phase of HCV infection and facilitates the progression of fibrosis and development of HCC.

In chronic hepatitis C infection, HCV viral replication per se may be dominant in the overall process of hepatocarcinogenesis associated with HCV infection. This study complements studies of HCV infection in other populations and indicates that in the Egyptian population suffering from a high burden of hepatitis C genotype-4 virus the strikingly high rates of hepatocarcinogenisis result from a combination of this direct viral effect and the influence of an array of metabolic factors resulting from virus-induced insulin resistance.

Our results lay a foundation for a follow up cohort study with larger sample size and including diabetic and non-diabetic CHC patients with and without fibrosis that would have value to illustrate the role of IR as a separate metabolic factor for HCC development and enable investigation of the role of other individual metabolic signals such as adiponectin, and leptin which may have particular involvement in hepatocarcinogenesis in patients infected with HCV-4. A better understanding of IR involvement in HCV-4 mediated HCC may point to potential for benefit of therapeutic interventions aimed at control of IR, and IR-associated signals, in these patients.

References

Lauer GM, Walker BD: Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 41-52. 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107

Chiaramonte M, Stroffolini T, Vian A, Stazi MA, Floreani A, Lorenzoni U, Lobello S, Farinati F, Naccarato R: Rate of incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with compensated viral cirrhosis. Cancer 1999, 85: 2132-2137. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2132::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-H

Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F: Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 2004, 127: S35-S50. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014

Zekri AR, Bahnassy AA, Abdel-Wahab SA, Khafagy MM, Loutfy SA, Radwan H, Shaarawy SM: Expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in relation to apoptotic genes in Egyptian liver disease patients associated with HCV-genotype-4. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009, 24: 416-28. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05699.x

Sheikh MY, Choi J, Qadri I, Friedman JE, Sanyal AJ: Hepatitis C virus infection: molecular pathways to metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 2008, 47: 2127-2133. 10.1002/hep.22269

Hui JM, Sud A, Farrell GC, Bandara P, Byth K, Kench JG, McCaughan GW, George J: Insulin resistance is associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and fibrosis progression. Gastroenterology 2003, 125: 1695-704. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.032

Kawaguchi T, Sata M: Importance of hepatitis C virus-associated insulin resistance: therapeutic strategies for insulin sensitization. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16: 1943-1952. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i16.1943

Hung CH, Lee CM, Chen CH, Hu TH, Jiang SR, Wang JH, Lu SN, Wang PW: Association of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines with insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009, 29: 1086-1093. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01991.x

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmound K, Thun MJ: Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 2003, 348: 1625-1638. 10.1056/NEJMoa021423

Del Campo JA, Romero-Gómez M: Steatosis and insulin resistance in hepatitis C: A way out for the virus? World J Gastroenterol 2009, 15: 5014-5019. 10.3748/wjg.15.5014

Hung HC, Wang JH, Hu TH, Chen CH, Chang KC, Yen YH, Kuo YH, Tsai MC, Lu SN, Lee CM: Insulin resistance is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16: 2265-2271. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2265

Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, Degroote J, Denk F: Histopathological staging and grading of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995, 22: 696-699. 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6

Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA: World health organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of digestive system. Lyon IARC Press 2000, 157-202.

Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI: Clearance of HCV by combination therapy of pegylated interferon α-2a and ribavirin improves insulin resistance. Gut Liver 2009, 3: 108-115. 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.2.108

Moucari R, Ripault M-P, Martinot-Peignoux M, Voitot H, Cardoso A-C, Stern C, Boyer N, Maylin S, Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Vidaud M, Valla D, Bedrossa P, Marcellin P: Insulin resistance and geographical origin: major predictors of liver fibrosis and response to peginterferon and ribavarin in HCV-4. Gut 2009, 58: 1662-1669. 10.1136/gut.2009.185074

Esteghamati A, Ashraf H, Khalzadeh O, Zandieh A, Nakhjavani M, Rashidi A, Haghazali M, Asgari F: Optimal cut-off of homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome: third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007). Nutrition & Metabolism 2010, 7: 26-33.

Sink A: Insulin resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C. TMJ 2007, 57: 240-244.

Hu Y, Shahidi A, Park S, Guilfoyle D, Hirshfield I: Detection of extrahepatic hepatitis C virus replication by a novel, highly sensitive, single tube nested polymerase chain reaction. Am J Clin Pathol 2003, 119: 95-100. 10.1309/33TAJLB748KLMXVG

Shaker O, Ahmed A, Doss W, Abdel-Hamid M: MxA expression as marker for assessing the therapeutic response in HCV genotype 4 Egyptian patients. J Viral Hepat 2010, 17: 794-799. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01241.x

Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB: Diabetes increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population based case control study. Gut 2005, 54: 533-539. 10.1136/gut.2004.052167

Chen CL, Yang HI, Yang WS, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, You SL, Wang LY, Sun CA, Lu SN, Chen DS, Chen CJ: Metabolic factors and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by chronic hepatitis B/C infection: a follow-up study in Taiwan. Gastroenterology 2008, 135: 111-121. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.073

Lai MS, Hsieh MS, Chiu YH, Chen TH: Type 2 Diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: A cohort study in high prevalence area of hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology 2006, 43: 1295-1302. 10.1002/hep.21208

Puri P, Sanyal AJ: Role of obesity, insulin resistance, and steatosis in hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Liver Dis 2006, 10: 793-819. 10.1016/j.cld.2006.08.002

Harrison SA: Correlation between insulin resistance and hepatitis C viral load. Hepatology 2006, 43: 1168-1169.

Veldt BJ, Chen W, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, de Knegt RJ, Zeuzem S, Manns MP, Hansen BE, Schalm SW, Janssen HL: Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology 2008, 47: 1856-1862. 10.1002/hep.22251

Douglas MW, George J: Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2009, 15: 4356-4364. 10.3748/wjg.15.4356

Gomez MR: Hepatitis C and insulin resistance: Steatosis, fibrosis and non response. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006, 98: 605-615.

Saito K, Inoue S, Saito T, Kiso S, Ito N, Tamura S, Watanabe H, Takeda H, Misawa H, Togashi H, Matsuzawa Y, Kawata S: Augmentation effect of postprandial hyperinsulinemia on growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2002, 51: 100-104. 10.1136/gut.51.1.100

El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE: Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004, 126: 460-468. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.065

Siegel AB, Zhu AX: Metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2009, 115: 5651-5661. 10.1002/cncr.24687

Moucari R, Asselah T, Cazals-Hatem D, Voitot H, Boyer N, Ripault MP, Martinot-Peignoux M, Maylin S, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Paradis V, Vidaud M, Valla D, Bedossa P, Marcellin P: Insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C: association with genotypes 1 and 4, serum HCV RNA level, and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134: 416-423. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.010

Fartoux L, Poujol-Robert A, Guechot J, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L: Insulin resistance is a cause of steatosis and fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2005, 54: 1003-1008. 10.1136/gut.2004.050302

Hsu CS, Liu CJ, Liu CH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Lai MY, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Chen DS: High hepatitis C viral load is associated with insulin resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int 2008, 28: 271-277.

Paradis V, Perlemuter G, Bonvoust F, Dargere D, Parfait B, Vidaud M, Conti M, Huet S, Ba N, Buffet C, Bedossa P: High glucose and hyperinsulinemia stimulate connective tissue growth factor expression: a potential mechanism involved in progression to fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2001, 43: 738-744.

Bartosch B, Thimme R, Blum H, Zoulim F: Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol 2009, 51: 810-820. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.008

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ: The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005, 365: 1415-1428. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7

Nathan C: Epidemic inflammation: pondering obesity. Mol Med 2008, 14: 485-492.

Bakwill F, Mantovani A: Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001, 357: 539-545. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0

Periscoe M, Capasso M, Persico E, Svelto M, Russo R, Spano D, Crocè L, La Mura V, Moschella F, Masutti F, Torella R, Tiribelli C, Iolascon A: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) expression and hepatitis C virus-related chronic hepatitis: Insulin resistance and response to antiviral therapy. Hepatology 2007, 46: 1009-1015.

Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL, Dipietro L, Cline GW, Shulman GI: Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 2003, 300: 140-1142.

Koike K: Hepatitis C virus contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis by modulating metabolic and intracellular signaling pathways. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007, Suppl 1: S108-S111.

Pazienza V, Clement S, Pugnale P, Conzelman S, Foti M, Mangia A, Negro F: The hepatitis C virus core protein of genotypes 3a and 1b downregulates insulin receptor substrate 1 through genotype-specific mechanisms. Hepatology 2007, 45: 1164-1171. 10.1002/hep.21634

Romero-Gomez M: Insulin resistance and hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2006, 12: 7075-7080.

Pazienza V, Vinciguerra M, Andriulli A, Mangia A: Hepatitis C virus core protein genotype 3a increases SOCS-7 expression through PPAR-{gamma} in Huh-7 cells. J Gen Virol 2010, 91: 1678-1686. 10.1099/vir.0.020644-0

Acknowledgements

Dr. Zeinab Aly el Din, Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University is thanked for her great help in collection of specimens and data from the patients enrolled in the study. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AAM performed the research; SAL developed the plan of the study and wrote the paper; JC analyzed the molecular data and evaluated and edited the draft manuscript; AGMH contributed analytical tools and reagents and IS collected samples, gathered clinical data and contributed to the drafting data tables.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, A.A., Loutfy, S.A., Craik, J.D. et al. Chronic hepatitis c genotype-4 infection: role of insulin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Virol J 8, 496 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-496

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-496