Abstract

Background

Stents are recommended in patients with dysphagia caused by esophageal stricture, but an ideal stent does not currently exist. Thus, studies on new esophageal stents are necessary, and suitable animal models are desperately needed for these studies. The aim of this study was to establish a model of malignant esophageal stricture in rabbit for studies on stent innovation.

Methods

A total of 38 New Zealand white rabbits were used in this study. Using the endoscopic submucosal injection technique, VX2 fragments were inoculated into the submucosal layer of the rabbit thoracic esophagus, and an endoscopic follow-up was subsequently performed to observe the tumor development and progression. The self-expandable metal stents were randomly deployed in rabbits with severe esophageal stricture to investigate the safety and feasibility of the animal models for stenting.

Results

An endoscopic implantation procedure for VX2 tumors was completed in 34/38 rabbits, and tumor development was confirmed in 30/34 animals. The success rate of the endoscopic implantation and tumor development were 89.4% (95% CI, 79.6% to 99.2%) and 88.2% (95% CI, 76.9% to 99.5%) respectively. During the endoscopic follow-up period, severe esophageal stricture occurred in 22/30 rabbits with a rate of 73.3% (95% CI, 57.5% to 89.1%), and 12/22 models received stent placement. During and after stent implantation, no severe stent-related complication or mortality occurred in the animal models. The rabbits that received stent placement survived longer than those without stent implantation (the mean survival time: 53.9 days versus 40.3 days, P = 0.016).

Conclusion

The endoscopic method is a safe and effective method for establishing a malignant esophagostenosis model in rabbits. This model can simulate the human body environment for stent deployment and is an excellent tool for the study of stent innovation for the treatment of esophageal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the eighth most common cancer worldwide [1, 2]. Treatment of esophageal carcinoma remains challenging but is best approached using a multidisciplinary team. Stents are recommended in patients with dysphagia caused by esophageal stricture, and an optimal stent should have features, such as being easy to deploy, staying in place, reducing tumor ingrowth or overgrowth, and causing minimal to no discomfort [3–5]. However, the ideal stent does not currently exist, and studies on new esophageal stents are necessary and significant. Thus, suitable animal models are desperately needed for these studies.

Theoretically, a good animal model of EC for stenting should be able to mimic the esophagostenosis features of the human disease and be sufficiently large to perform minimally invasive procedures designed for humans. However, there is currently a severe lack of an excellent animal model of EC to study stents [6–9].

The VX2 tumor model, which was originally proposed by Shope and Hurst [10] in 1933, has been developed in the organs of rabbits, including the liver, kidney, lung, head and neck [11–14]. Although the rabbit model belongs to moderate-to-large-sized models and has been used to study EC in relevant research, there have been no reports on establishment of a rabbit model on malignant esophagostenosis, which is available for stent implantation.

Here, we introduce an endoscopic method for the development of a rabbit model of malignant esophagostenosis, and further investigate the safety and feasibility of stent implantation in this model. This is the first study where rabbits with esophageal malignant tumors were used for stent development procedures.

Material and methods

Animals and tumors

Male or female New Zealand White rabbits weighing between 2.5 and 3.0 kg were obtained from The Jiangsu Agricultural Academy of Science in China and food and water were provided ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Subcommittee at Nanjing Medical University.

Donor rabbits and implantation preparation

Rabbits with hind limb tumors (donor) were used to propagate and maintain VX2 tumors. Approximately 2 to 3 pieces of thawed VX2 tumor tissue fragments (approximately 0.5 mm3) that, were previously stored in liquid nitrogen were injected deep into the hind limb of gluteal muscles of rabbits anesthetized using an intramuscular injection of 35-mg/kg pentobarbital sodium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Three weeks after implantation, the animals were sacrificed and the hind limb tumors were harvested and immediately processed. All VX2 tumors were cleaned from the surrounding tissue and gross necrotic portions of the tumors were removed.

The collected tumors were cut into small pieces (approximately 0.5 mm3) and preserved in saline for fragment implantation. approximately 0.3 ml saline solution with 4 pieces of tumor fragments were placed in a 2-ml syringe on ice until they were injected into the recipient rabbit’s esophagus.

Endoscopic implantation of VX2 tumors

The rabbits were first anesthetized after 24 h of fasting with free access to water and then placed in the left lateral decubitus position. An endoscope (Olympus GIFXP260, Japan) was inserted into the thoracic esophagus. Using a fine endoscopic needle (the inner core of an endoscopic needle, Olympus, MAJ-68, 23-gauge), 0.5 ml saline was injected into the submucosal layer to elevate the mucosa layer. Next, a puncture was made using a modified endoscopic needle (Olympus, MAJ-68, with an oblique cut in the front, approximately 20-gauge) across the mucosa into the submucosal layer and the success of the puncture was confirmed by further elevation of the mucosa when saline was injected. About 0.3 ml saline containing 4 tumor pieces was then injected into the submucosal layer of rabbits esophagus (an additional movie file shows this in more detail, see Additional file 1). A second 0.3 ml saline was injected to rinse the needles and to collect the remaining pieces. After implantation, the rabbits were given an auricular vein infusion and fasted for 24 h.

Additional file 1: Endoscopic method for implantation of VX2 tumors.(MP4 8 MB)

Endoscopic follow-up

Endoscopic examinations were performed once a week after implantation to observe tumor growth and the degree of esophageal stenosis. Tumor development was determined using endoscopy and biopsy. Three grades were used to evaluate the esophageal stenosis under endoscopy: mild stenosis for tumors less than or equal to 1/3 of the lumen diameter, moderate stenosis for tumors more than 1/3 but less than or equal to 2/3 of the lumen diameter, and severe stenosis for tumors more than 2/3 of the lumen diameter.

Stent implantation

The stents was randomly implanted in some models when the degree of esophageal stricture became severe, the remainder without stents acted as controls for the survival study. The self-expandable metal stent (8 mm in diameter and 25 mm in length) was designed and manufactured (Garson Company, Changzhou City, China), and its partial length was covered with a silicone membrane (Figure 1). Using X-ray fluoroscopy, a guidewire was first inserted across the stricture into the stomach. Next, the delivery device was gently passed over the guidewire, and the restraining tube was retracted to release the stent within the stricture (Figure 2). As soon as the stent was deployed, correct positioning of the stent was assessed endoscopically. Next, endoscopic and fluoroscopic examinations were performed every week to observe the immediate and late complications of the models, inclouding fistulization/perforation, bleeding, stent migration, esophageal restenosis, airway compromise and procedure-related mortality.

Procedure for stent placement. (A) Fluoroscopy showed a malignant stricture (black arrow) in the thoracic esophagus of a rabbit. The endoscope (yellow arrow) was used for injection of the contrast. (B) Fluoroscopic view of the stent implanted at the desired location, which was also confirmed using an endoscope (yellow arrow). (C) Endoscopic view of the tumor intra-luminal growth (yellow arrow); the esophageal lumen was on the right of the tumor (black arrow). (D) After stent placement, the endoscopic view of the stent at an ideal location revealed that the tumor was outside of stent, but within the extension of the stent (yellow arrow).

Survival time

The survival time of all rabbits demonstrated severe esophageal stricture was recorded, independent of the status of stent placement. The rabbits were fed separately in cages to daily observe the quantity of food and water. Paste food or liquid food (vegetable juices) were provided for animals with dysphagia or a 50% reduction of food intake. A humane endpoint was used in this study, in which the animal models were humanely euthanized when they could not have any food or water for several days and their health was extremely weak, such that they could not stand. For the euthanasia procedure, the animal was first anesthetized via an intramuscular injection of 35-mg/kg pentobarbital sodium using the ear venous, and then with a injection of 30 ml air.

Data analysis

We calculated the success rate of tumor production, inclouding that of endoscopic implantation and tumor development. The rate of severe esophageal stricture and the rate of immediate and late complication of stents placemen were also investigated. The Kaplan-Meier method with the log rank test was used to analyze the survival of rabbits with or without stents. The statistical significance was set at the P < 0.05 level. All statistical tests were performed with the SPSS 16.0 software.

Results

Success rate of tumor production

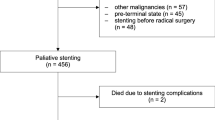

A total of 38 rabbits were used in this study. Thirty-four rabbits were successfully implanted with VX2 fragments in the esophagus and the success rate of endoscopic implantation was 89.4% (95% CI, 79.6% to 99.2%). Four rabbits were removed from the study because of the esophageal perforations during the endoscopic implantation and two injured rabbits (5.3%) died after conservative treatments. After implantation, tumor development was confirmed (Figure 3) in 30/34 rabbits and the success rate was 88.2% (95% CI, 76.9% to 99.5%).

Degree of esophageal stenosis

During the endoscopic follow-up after tumor implantation, severe stricture was observed in 22/30 rabbits (Figure 4), and the rate was 73.3% (95% CI, 57.5% to 89.1%). Mild-to-moderate stricture was observed in 8/30 rabbits and the rate was 26.7% (95% CI, 10.9% to 42.5%).

Complications of stent placement

Among 22 models with severe esophageal stricture, 12 rabbits were smoothly implanted with esophageal stents, and the remaining 10 rabbits served as controls for the survival study. During and after stent deployment, stent migration, esophageal restenosis (Figure 5) and airway compromise occurred in 2/12 (16.7%), 1/12 (8.3%) and 1/12 (8.3%) rabbits respectively. There was no severe stent-related complication or mortality.

Survival time of the models

The longest survival time of rabbits with stent implantation was 74 days and the shortest survival time was 28 days with a mean survival time of 53.9 ± 13.4 days. However, the longest survival time of rabbits without stents deployed was 59 days, and the shortest survival time was 24 days with a mean survival time of 40.3 ± 11.3 days, which was significantly different (P = 0.016) in the survival time between the two groups (Figure 6).

Survival curve of the rabbits with severe esophagostenosis. Graph of Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showing a significant survival benefit (P < 0.05) for models with stent placement (blue curve), compared to those without stent deployment, but similarly demonstrated severe esophagostenosis (green curve).

Discussion

Despite having a higher success rate of tumor growth [15, 16] compared to VX2 cells, the VX2 fragments were difficult to implant into the rabbit esophagus, independent of the endoscopic or surgical procedure selected. Compared with the surgical method, the endoscopic procedure was minimally invasive, but it increased the incidence of esophageal perforation when using large needles to implant the VX2 fragments. Thus, we introduced the submucosal injection technique [17, 18] for our endoscopic procedure to decrease the complications by enlarging the space of the submucosal layer of the esophagus. In the current study, the endoscopic method demonstrated a high success rate of implantation indicating that it is a safe and effective method for the establishment of a malignant esophagostenosis model.

Esophageal stenosis is a predominant pathological feature of EC in the clinic because it promotes rapid deterioration and death [19, 20]. In the present study, our model showed a high rate of severe esophagostenosis, which is a very important indication for stenting. We proposed that this characteristic formation might be associated with the tumor submucosal layer implantation, which contributs to the tumor intra-luminal growth.

In many preclinical studies, large-sized animal models, such as the dog and pig, have been generally used for stenting, but these animals were not under disease conditions, despite the fact that they could simulate the human body environment for esophageal stent deployment. Thus, they were only used to assess the safety of stenting [21–23]. Furthermore, small animal models, such as mice, were immunodeficient and may potentially exhibit malignant esophagostenosis, this, could be used to study the efficiency and mechanism of stenting; however, these small animal models can not allow for stenting, according to the procedures designed for humans [24–26]. Thus, they are unsuitable and are seldom used for studies on stents. The rabbit model of malignant esophagostenosis developed in this study not only exhibits the feature of malignant esophagostenosis, commendably mimicking that of human EC and showing potential use for research on the efficiency and mechanism of stents, but it could also simulate the human body environment for stenting according to the procedures used for humans.

The overall complication rate and primary success rate of self-expanding esophageal stenting in clinical research were approximately 30% and 97.2%, respectively [27, 28]. In this study, all of the procedures of the stent implantation were smoothly completed, and there was no rabbit that had severe stent-related complications [29, 30], such as fistulization/perforation or bleeding, and there was no procedure-related mortality, although the events of stent migration, esophageal re-stenosis and airway compromise occurred with a total complication rate of 33.3% during and after stent implantation. These results indicated that it is safe and feasible to implant an esophageal stent into our animal models. Moreover, the survival time of rabbits with stent placement was longer compared to rabbits without stent deployment indicating that our models could endure stent implantation and benefit from the stents. This finding suggested that our animal model represents an ideal tool for the study of esophageal stents for EC.

The limitation of our animal model is that it is an orthotopic allograft tumor model and cannot be maintained the routine course of esophageal cancers. This study focused on whether the animal model is suitable for stent implantation and may neglect other features and utility of this animal model.

In conclusion, the endoscopic method is safe and effective for the development of a rabbit model of malignant esophagostenosis to mimic the progression of this human disease. This model can simulate human the body environment for stent deployment and is an excellent tool for studying stent innovation for the treatment of esophageal cancer.

References

Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD: Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013, 381: 400-412.

Zhang HZ, Jin GF, Shen HB: Epidemiologic differences in esophageal cancer between Asian and Western populations. Chin J Canc. 2012, 31: 281-286.

Hirdes MM, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD: Stent placement for esophageal strictures: an update. Expert Rev Med Devic. 2011, 8: 733-755.

Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD: Expandable stents for malignant esophageal disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011, 21: 377-388.

Shayan I, Richard K: Esophageal stents: past, present, and future. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2010, 12: 178-190.

Wu X, Zhang J, Zhen R, Lv J, Zheng L, Su X, Zhu G, Gavine PR, Xu S, Lu S, Hou J, Liu Y, Xu C, Tan Y, Xie L, Yin X, He D, Ji Q, Hou Y, Ge D: Trastuzumab anti-tumor efficacy in patient-derived esophageal squamous cell carcinoma xenograft (PDECX) mouse models. J Transl Med. 2012, 10: 180-

Ohara T, Takaoka M, Sakurama K, Nagaishi K, Takeda H, Shirakawa Y, Yamatsuji T, Nagasaka T, Matsuoka J, Tanaka N, Naomoto Y: The establishment of a new mouse model with orthotopic esophageal cancer showing the esophageal stricture. Canc Lett. 2010, 293: 207-212.

Pauli EM, Schomisch SJ, Furlan JP, Marks AS, Chak A, Lash RH, Ponsky JL, Marks JM: Biodegradable esophageal stent placement does not prevent high-grade stricture formation after circumferential mucosal resection in a porcine model. Surg Endosc. 2012, 26: 3500-3508.

Ji JS, Lee BI, Kim HK, Cho YS, Choi H, Kim BW, Kim SW, Kim SS, Chae HS, Choi KY, Maeng LS: Antimigration property of a newly designed covered metal stent for esophageal stricture: an in vivo animal study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011, 74: 148-153.

Shope RE, Hurst EW: Infectious papillomatosis of rabbits: with a note on the histopathology. J Exp Med. 1933, 58: 607-624.

Mine T, Murata S, Ueda T, Onozawa S, Onda M, Naito Z, Kumita S: Comparative study of cisplatin-iodized oil suspension and emulsion for transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of rabbit VX2 liver tumors. Hepatol Res. 2012, 42: 473-481.

McDannold N, Fossheim SL, Rasmussen H, Martin H, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K: Heat-activated liposomal MR contrast agent: initial in vivo results in rabbit liver and kidney. Radiology. 2004, 230: 743-752.

Shen N, Wu H, Xu X, Wang J, Hoffman MR, Rieves AL, Zhou L: Cervical lymph node metastasis model of pyriform sinus carcinoma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2009, 71: 129-134.

Valdivia Y, Alvarado M, Wong K, He TC, Xue Z, Wong ST: Image-guided fiberoptic molecular imaging in a VX2 rabbit lung tumor model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011, 22: 1758-1764.

Sun JH, Zhang YL, Nie CH, Yu XB, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS: Considerations for two inoculation methods of rabbit hepatic tumors: pathology and image features. Exp Ther Med. 2012, 3: 386-390.

Virmani S, Harris KR, Szolc-Kowalska B, Paunesku T, Woloschak GE, Lee FT, Lewandowski RJ, Sato KT, Ryu RK, Salem R, Larson AC, Omary RA: Comparison of two different methods for inoculating VX2 tumors in rabbit livers and hind limbs. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008, 19: 931-936.

Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T: Dynamic submucosal injection technique. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010, 20: 497-502.

Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM: Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006, 41: 929-942.

de Wijkerslooth LR, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD: Endoscopic management of difficult or recurrent esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011, 106: 2080-2091.

Siersema PD: Treatment options for esophageal strictures. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008, 5: 142-152.

Endo M, Kaminou T, Ohuchi Y, Sugiura K, Yata S, Adachi A, Kawai T, Takasugi S, Yamamoto S, Matsumoto K, Hashimoto M, Ihaya T, Ogawa T: Development of a new hanging-type esophageal stent for preventing migration: a preliminary study in an animal model of esophagotracheal fistula. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012, 35: 1188-1194.

Guo JH, Teng GJ, Zhu GY, He SC, Deng G, He J: Self-expandable stent loaded with 125I seeds: feasibility and safety in a rabbit model. Eur J Radiol. 2007, 61: 356-361.

Baron TH, Burgart LJ, Pochron NL: An internally covered (lined) self-expanding metal esophageal stent: tissue response in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006, 64: 263-267.

Kim EY, Park YS, Shin JH, Cho YJ, Shin DH, Yoon HK, Song HY: The effectiveness of erythromycin in reducing stent-related tissue hyperplasia: an experimental study with a rat esophageal model. Acta Radiol. 2012, 53: 868-873.

Kim EY, Shin JH, Jung YY, Shin DH, Song HY: A rat esophageal model to investigate stent-induced tissue hyperplasia. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010, 21: 1287-1291.

Kapisiz A, Karabulut R, Sonmez K, Turkyilmaz Z, Poyraz A, Gulbahar O, Onal B, Ozbayoglu A, Basaklar AC: Effect of stent placement, balloon or cutting balloon dilatation on stricture formation after caustic esophageal burn in rats. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011, 21: 258-262.

Schoppmann SF, Langer FB, Prager G, Zacherl J: Outcome and complications of long-term self-expanding esophageal stenting. Dis Esophagus. 2013, 26: 154-158.

Thompson AM, Rapson T, Gilbert FJ, Park KG: Endoscopic palliative treatment for esophageal and gastric cancer: techniques, complications, and survival in a population-based cohort of 948 patients. Surg Endosc. 2004, 18: 1257-1262.

Ramirez FC, Dennert B, Zierer ST, Sanowski RA: Esophageal self-expandable metallic stents–indications, practice, techniques, and complications: results of a national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997, 45: 360-364.

Wang MQ, Sze DY, Wang ZP, Wang ZQ, Gao YA, Dake MD: Delayed complications after esophageal stent placement for treatment of malignant esophageal obstructions and esophagorespiratory fistulas. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001, 12: 465-474.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yi Miao at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University for providing the VX2 tumor.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 81172266/H1617 (http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/nsfc/cen/bsdt/jggb.html), and by the Jiangsu Province Social Development Fund under Grant No. BL2012031 (http://www.jskjjh.gov.cn).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing or financial interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZF, JH, JS, XW and GX conceived, designed and performed the experiments. YZ, XT, YS, HS and ZL analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Shuang, J., Xiong, G. et al. Establishing a rabbit model of malignant esophagostenosis using the endoscopic implantation technique for studies on stent innovation. J Transl Med 12, 40 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-12-40

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-12-40