Abstract

We describe a case of a patient with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and cardiac conduction abnormalities who presented a strong family history of sudden cardiac death. Genetic screening of lamin A/C gene revealed in proband the presence of a novel missense mutation (R189W), near the most prevalent lamin A/C mutation (R190W), suggesting a "hot spot" region at exon 3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lamin A/C gene (LMNA) mutations have been causally linked to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), accounting for 6% to 8% of all idiopathic DCM up to 40% when conduction disorders are present [1, 2]. In particular, LMNA-related DCM is characterized by progressive heart failure, variable involvement of skeletal muscle, atrioventricular block and/or tachyarrhythmias [2]. Furthermore, LMNA mutations have been shown to be associated to a very poor prognosis, with a high rate of sudden cardiac death, and severe forms of heart failure necessitating heart transplantation [3, 4].

We report a case report of DCM with a family history of sudden cardiac death (3 brothers dead for sudden cardiac death) in which a novel LMNA missense mutation was found. In addition, we discuss the role of genetic testing for the LMNA gene in routine clinical practice.

Case presentation

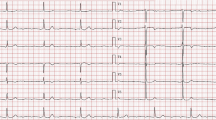

The proband was a 55 year-old woman referred to our Cardiology Department for fatigue, palpitations and cardiac dyspnea at rest (NYHA Class IIa). LV function assessed by echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 36% with dilatation of the left ventricle (end-diastolic diameter 59 mm) and a wall motion score index of 2 (global hypokinesia). During a Holter recording the patient presented premature ventricular beats with an incidence rate of 5 per hour. No complex tachyarrhythmias were observed (Table 1). DCM was diagnosed on the basis of Word Health Organization criteria [5]. Moreover, the patient underwent stress echocardiography that showed contractile reserve with normalization of function at peak stress.

The proband was prescribed ACE-inhibitors and is followed-up at our out-patient clinic. At last visit (8 years after first observation) the patient is asymptomatic for dyspnea (NYHA Class I) and/or palpitations. The echocardiogram shows a recovery of LV function with an ejection fraction of 57% and sporadic premature ventricular beats at Holter recording.

Family history revealed that three proband's brothers died of sudden cardiac death at the age of 72, 44 and 22 years, respectively (Figure 1). After genetic counselling, on the basis of clinical data and family history, the patient underwent to genetic screening of LMNA gene mutations.

Pedigree of the family. Individuals are indicated by generation and pedigree number. The proband is indicated by arrow and affected status is indicated by filled symbol. The presence (+) or absence (-) of the mutation is indicated for the genetically tested family members. Chromatogram below demonstrates the heterozygous mutation.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing was performed in the proband by screening of the 12 coding exons of LMNA gene amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers encompassing the protein coding region of exons as well as the immediate intronic regions essential for splicing, as described previously [6]. Sequencing was performed with a capillary sequencer CEQ 8800 (Beckman Coulter, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

A novel heterozygous missense mutation cytosine-to-thymine at nucleotide 565 in exon 3 was identified in the proband. The nucleotide change predicts an arginine (basic) to tryptophan (hydrophobic) substitution (R189W) in a conserved residue located in the coil 1b of the alpha-helical rod domain (Figure 2) (GenBank accession n. NM_170707.2).

The mutation was confirmed by PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis by using specific primers (forward 5'-GCAGCAGCCCACCTCTC-3'and reverse 5'-AAGGCGAGCTCTGCACAC-3') and the restriction enzyme Tau I that cut the wild-type sequence into two fragments of 167 bp and 134 bp. In the presence of 565c>t transition, Tau I does not recognize the restriction site and leaves the 301 bp PCR product uncutted.

The R189W mutation was neither identified in 100 chromosomes from 50 normal volunteers (≥ 30 years of age) who were randomly selected from our control genomic store, nor previously published in the LMNA literature as benign polymorphism, indicating it is likely not a common variant. A total of three synonymous substitutions were also found in the proband, but none of these nucleotide changes predicts a change in aminoacid sequence (Table 1). These 3 silent variants were already described and registered in the databases and have no conclusive or known pathogenicity.

No genetic material or medical records were available for parents and 2 sisters of the proband. After giving informed consent, the other family members received genetic counselling and clinical screening, and underwent peripheral blood sampling for genetic testing.

Clinical investigation included resting cardiologic evaluation, 12-lead electrocardiogram and 2-dimensional echocardiography study. During genetic screening, the specific R189W mutation was identified in three asymptomatic nephews (III-1, 37 years; III-2, 31 years and III-3, 32 years) and excluded in the two sons of the proband (III-5 and III-6). The mutation carriers III-1, III-2, and III-3 were asymptomatic and presented normal ECG.

One nephew (III-10, 30 years) underwent magnetic resonance testing for the confirm of non-compaction cardiomyopathy suspected at echocardiography. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a sponge-like appearance and trabeculated fibres in the lateral wall, but did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria for ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (Figure 3). The subject is unavailable for genetic screening at the moment.

Discussion

Our report describes a family in which proband and clinically unaffected family members harbour a novel potentially pathogenic mutation (R189W) in LMNA gene.

At the present, LMNA gene is the most frequent disease-associated gene for familial DCM with conduction system disease. The LMNA gene encodes the two differentially spliced proteins lamin A and lamin C, the major components of the nuclear lamina, which localizes at the nucleoplasmic surface of the inner nuclear membrane as a meshwork structure [2]. Lamin interacts directly with the chromatin and also with the integral proteins of the inner nuclear membrane, thereby playing a role in maintaining the structural integrity and spatial organization of other inner nuclear membrane.

It is worth to mention that the most prevalent LMNA mutation "hot spot" in familial DCM is codon 190 in exon 3. The mutation R190W was initially described by Arbustini et al. in an Italian family with severe DCM and sudden cardiac death, and subsequently found in another family in Europe and other countries associated with conduction system disease and an ominous outcome [1, 7–9]. Codon 190 is localized in the protein domain coil 1b, an alphahelical segment of the central rod separated by short linkers, which is important for lamin B interaction and lamin A/C dimerization. Mutations in this domain, disrupting the coiled-coil fold of lamin A and C, may lead to a weaker nuclear lamina with subsequent mechanical stress damage by muscle contraction and abnormal mechano-transduction [10]. Our novel mutation is located in the previous codon 189, leading to the same aminoacid substitution (R189W), suggesting a "hot spot" region at exon 3 (Figure 2).

LMNA is not only the most frequent gene found in DCM, but it has also been shown to be associated with a very poor prognosis and a high mortality rate [3, 4]. A meta-analysis showed that LMNA mutations carriers are at very high risk for arrhythmogenic complications, with a class I indication to defibrillator implant. Most cases, in fact, experience sudden cardiac death and show malignant course with severe forms of heart failure necessitating heart transplantation [3]. Recently, Pasotti et al. have shown that dilated cardiomyopathies caused by LMNA gene defects are highly penetrant, have adult onset, are malignant conditions characterized by a high rate of severe left ventricular dysfunction and life-threatening arrhythmias, that should lead to considering special indications for ICD implantation in this group of patients [4].

Therefore, the severity of LMNA mutations strengthens the need for genetic testing of LMNA in order to risk stratify DCM patients and their relatives, and indicate an early treatment so to avoid the main complications of the disease [2, 11].

Genetic counselling is becoming a mainstay in the clinical management of familial diseases. It is important to appropriately select the patients (and families) to be screened in order to identify the subset that should be followed-up and treated accordingly.

Genetic testing is often the best way to provide risk estimates for asymptomatic patients. However, genetic tests remain generally expensive technologies that are labor-intensive and time-consuming. Therefore, routine and extensive genetic screening is impractical because of the genetic heterogeneity of DCM. Genetic testing is not appropriate for every patient, but it should be used in selected cases, such as patients with an established family history of severely affected relatives and at high risk of worse prognosis.

In particular, our results strengthen the evidence that genetic screening is indicating in idiopathic DCM with a positive family history in ≥ 2 closely related relatives [2]. These cases generally show an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and have underlying mutations in specific genes; some of these mutations are known to be associated with a more malignant phenotype.

Genetic testing unambiguously allows for early identification and diagnosis of individuals at greatest risk for developing DCM, allowing to focus clinical resources on high-risk family members. In addition, it is extremely important that family members receive careful counselling before and after testing on the potential risks.

Relative may carry the mutation but be asymptomatic, and the mutation may merely be a predisposing factor to disease in the presence of other factors, and so its presence alone does not allow accurate prediction of phenotype or prognosis. However, if a mutation is identified in asymptomatic individual, regular clinical cardiovascular screening (echocardiogram, ECG) is recommended to detect the first signs of disease that may be diminished by early treatment. If family members are found not to carry that mutation, they can be definitively diagnosed as unaffected, and the need for serial follow-up becomes unnecessary. In this case, they can be reassured that neither they nor their offspring will be at higher risk compared to the general population to develop these disorders.

The identification of the R189W mutation in our proband, led us to recognize three non-affected mutated carriers at higher risk of DCM who will benefit from regular clinical cardiac follow-up (echocardiogram, ECG) and early treatment. On the other hand, the exclusion of the causal mutation in two sons of the patient enables termination of the periodic clinical screening, allowing to address clinical resources only on high-risk family subjects.

Genetic testing is, therefore, clinically useful and should be recommended for DCM families.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Arbustini E, Pilotto A, Repetto A, Grasso M, Negri A, Diegoli M, Campana C, Scelsi L, Baldini E, Gavazzi A, Tavazzi L: Autosomal dominant dilated cardiomyopathy with atrioventricular block: a lamin A/C defect related disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 39: 981-990. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01724-2.

Colombo MG, Botto N, Vittorini S, Paradossi U, Andreassi MG: Clinical utility of genetic tests for inherited hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008, 6: 62-10.1186/1476-7120-6-62.

van Berlo JH, de Voogt WG, Kooi van der AJ, van Tintelen JP, Bonne G, Yaou RB, Duboc D, Rossenbacker T, Heidbüchel H, de Visser M, Crijns HJ, Pinto YM: Meta-analysis of clinical characteristics of 299 carriers of LMNA gene mutations: do lamin A/C mutations portend a high risk of sudden death?. J Mol Med. 2005, 83: 79-83. 10.1007/s00109-004-0589-1.

Pasotti M, Klersy C, Pilotto A, Marziliano N, Rapezzi C, Serio A, Mannarino S, Gambarin F, Favalli V, Grasso M, Agozzino M, Campana C, Gavazzi A, Febo O, Marini M, Landolina M, Mortara A, Piccolo G, Viganò M, Tavazzi L, Arbustini E: Long-term outcome and risk stratification in dilated cardiolaminopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 1250-1260. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.044.

Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, Maisch B, Mautner B, O'Connell J, Olsen E, Thiene G, Goodwin J, Gyarfas I, Martin I, Nordet P: Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996, 93: 841-842.

Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, Burgess D, Ludwigsen S, Peterson A, Li D, Jakobs P, Litt M, Porter CB, Rahko PS, Hershberger RE: Lamin A/C mutation analysis in a cohort of 324 unrelated patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2008, 156: 161-169. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.026.

Hermida-Prieto M, Monserrat L, Castro-Beiras A, Laredo R, Soler R, Peteiro J, Rodríguez E, Bouzas B, Alvarez N, Muñiz J, Crespo-Leiro M: Familial dilated cardiomyopathy and isolated left ventricular noncompaction associated with lamin A/C mutations. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 94: 50-54. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.029.

Kärkkäinen S, Reissell E, Heliö T, Kaartinen M, Tuomainen P, Toivonen L, Kuusisto J, Kupari M, Nieminen MS, Laakso M, Peuhkurinen K: Novel mutations in the lamin A/C gene in heart transplant recipients with end stage dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2006, 92: 524-526. 10.1136/hrt.2004.056721.

Perrot A, Hussein S, Ruppert V, Schmidt HH, Wehnert MS, Duong NT, Posch MG, Panek A, Dietz R, Kindermann I, Böhm M, Michalewska-Wludarczyk A, Richter A, Maisch B, Pankuweit S, Ozcelik C: Identification of mutational hot spots in LMNA encoding lamin A/C in patients with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009, 104: 90-99. 10.1007/s00395-008-0748-6.

Stewart CL, Kozlov S, Fong LG, Young SG: Mouse models of laminopathies. Exp Cell Res. 2007, 913: 2144-2156. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.026.

Mestroni L, Taylor MR: Lamin A/C gene and the heart: how genetics may impact clinical care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 1261-1262. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NB carried out the molecular genetic studies and wrote the manuscript; SV and MGC carried out the molecular genetic studies and have been involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content; GA performed cardiac MRI and has been involved in revising of the manuscript; UP and AB performed the clinical assessment of the subjects and has been involved in revising of the manuscript; MGA defined the study design and wrote the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Botto, N., Vittorini, S., Colombo, M.G. et al. A novel LMNA mutation (R189W) in familial dilated cardiomyopathy: evidence for a 'hot spot' region at exon 3: a case report. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 8, 9 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-8-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-8-9