Abstract

In spite of the considerable amount of experimental, clinical and epidemiological research about the consumption of red meat, total fats, saturated/unsaturated fatty acids and cholesterol with regard to the risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC), the issue remains controversial. The general belief is a reduction of red meat intake, and subsequent nutritional advice usually strongly recommends this. Paradoxically, beef together with whole milk and dairy derivatives, are almost the only sources for conjugated linoleic acid (CLAs) family. Furthermore CLAs are the only natural fatty acids accepted by the National Academy of Sciences of USA as exhibiting consistent antitumor properties at levels as low as 0.25 – 1.0 per cent of total fats. Beside CLA, other polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) belonging to the essential fatty acid (EFA) n-3 family, whose main source are fish and seafood, are generally believed to be antipromoters for several cancers. The purpose of this work is to critically analyze the epidemiological and experimental evidence by tentatively assuming that the reciprocal proportions of saturated fats (SA) plus cholesterol (CH) versus CLAs levels in fatty or lean beef may play an antagonistic role underlying the contradictory effects reported for red meats consumption and CRC risk. Recent results about meat intake and risk for CRC in Argentina have shown an unexpected dual behaviour related to the type of meats. Fatty meat derivatives, such as cold cuts and sausages, mainly prepared from fatty beef (up to 37% fat) were associated with higher risk, whereas high consumption of lean beef (< 15% fat) behaved as a protective dietary habit. CLA is located in the interstitial, non-visible, fat evenly distributed along muscle fibres as well as in subcutaneous depots. Visible fat may be easily discarded during the meal, whereas interstitial fats will be eaten. The remaining intramuscular fat in lean meats range from 25 to 50 g/Kg (2.5 to 5%). The proportion of CLA/SA+CH for lean beef eaters is 0.09 and the fatty mets 0.007 (g/100 g). As a consequence, the beneficial effects of minor amounts of CLA may be relatively enhanced in lean meat compared to fatty meat sub-products which contain a substantial amount of saturated fatty acids and cholesterol, as in cold cuts and cow viscera.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) is a wide term which groups together a mixture of positional and geometric isomers of C 18:2 fatty acids having conjugated, or contiguous, double bounds. These fatty acids arise along the ruminal process which ends with full saturation into stearic acid, a stepped pathway carried out by rumen bacteria.

These naturally occurring groups of dienoic derivatives of linoleic acid are incorporated into the fat in beef and milk of ruminants before the saturation process has been completed. Numerous beneficial effects are attributed to CLA, as in slowing down or even preventing tumor development. CLA decreases body fat storage in animal models [1] and promotes cardiovascular protection against atheroesclerosis [2]. A growing bulk of evidence shows that CLA, mainly as cis-9, trans-11, 18:2 n-6 derivatives, consistently produced antitumor effects, thus reducing the incidence, progression, number of metastases and tumor burden in rats and in murine models of mammary gland, colon, forestomach, skin and prostate tumorigenesis [3]. The evidence became so convincing that the National Academy of Science advised in 1996 that "Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) is the only fatty acid shown unequivocally to inhibit carcinogenesis in experimental animals" [4]. Beside CLA, other polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) belonging to the essential fatty acid (EFA) n-3 family, whose main source are fish and seafood, are generally believed to act as antipromoters for several cancers.

Interestingly enough for those populations having little o negligible fish intake as in the case of the mediterranean population of Argentina [5, 6], CLA remains the only source of beneficial fatty acids with respect to tumor prevention and cardiovascular protection.

The natural source of CLA are red meats and fatty dairy products, which are mainly bovine derivatives. However, these foods are also heavily suspected to be related to the higher risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) in humans. Indeed, as a consequence of a huge, and often contradictory, epidemiological, clinical and experimental amount of research, general advice has been sent to the population at large, suggesting that fatty beef, and to a lesser extent, whole fatty dairy derivatives, should be eaten less frequently, whereas the amount of dietary n-3 PUFAs might be increased.

CRC in humans continues to be a major challenge, since death rates due to colon carcinoma have not diminished appreciably within the past decades [7]. CRC is a major disease in Western populations, and diet may account for approximately 35% of the cases. The Argentinean food pattern, rich in beef and fats and poor in fibres and fish, may be related to an increased CRC risk. Our previous case-control studies on Argentinian people were consistent with these mentioned beliefs, showing that a high frequency of heavily roasted meat was associate with increased CRC risk. Saturated fatty acids and cholesterol also seemed to play an important role in this risk [8]. However, further characterization of meat consumption and risk for CRC by total intake as well as by different varieties of meat showed an unexpected dual behaviour related to the type of meats. Fatty meat derivatives, such as cold cuts and sausages, mainly prepared from fatty beef were consistently associated with higher risk, whereas high consumption of lean beef behaved as a protective dietary habit. High total meat consumption was not related to an increased risk of CRC in our subjects, even adjusting for energy and all macronutrients. Even though that the CRC risk has been attributed to other factors, as amount and varieties of nitrosocompounds [9] and heme ring of hemoglobin [10], several extensive reviews point to an increased risk linked somewhere to meat fat content. Indeed, different kinds of meat have similar levels of protein, so the mayor difference may lay in other components, for example, the amount and quality of lipid components. High fat diets, rich in cholesterol and saturated lipids, may favour cancer because of their high caloric content, or they could lead to increased levels of bile acids in the colonic rumen or a disbalance of the essential fatty acids metabolism [11].

On the other hand, fats from bovine milk and meat contain variable proportions of CLA. Interestingly, CLA is located in the interstitial, non-visible, fat evenly distributed along muscle fibres as well as in subcutaneous depots. Whereas the visible fat may be easily discarded and not consumed during the meal, interstitial fats will be eaten. The remaining invisible intramuscular total fat in lean meats range from 25 to 50 g/Kg (2.5–5%) [12]. As a consequence, beneficial effects of minor amounts of CLA will be relatively enhanced in lean meat compared to fatty meat sub-products since the latter contain thus a substantial amount of saturated fatty acids and cholesterol, as in cold cuts and cow viscera, diluting CLA.

In conclusion, whatever the beneficial or deleterious effects of CLA and saturated fatty acids/cholesterol mechanisms are, in the ruminant meats mixed natural fats may modulate opposite effects with regard to the risk of development of CRC in humans, according to their relative concentrations.

Presentation of the hypothesis

The aim of this review is to analyse the evidence demonstrating that reciprocal proportions of CLA and saturated fats/cholesterol may play an antagonistic role producing contradictory or no effects, as in the case of beef meat and dairy product intake with regard to risk of colon cancer.

Relative proportions of CLA and saturated fats/cholesterol in lean and fatty beefs meat

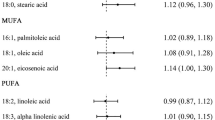

CLA concentrations in dairy products typically range from 2.9 to 8.92 mg/g fat, of which the 9-cis, 11-trans isomer makes up to 73 to 93% of the total CLA. Low concentrations of CLA are found in human blood and tissues [13]. The ratio between CLA and saturated fats plus cholesterol in fatty and lean meats, is shown in table 1[14].

The levels of CLA in commercial beef (g) and dairy products (ml) ranged from 1.2 and 6.2 mg/g of fat and 0.001 – 4.3 mg/g respectively [15]. The Argentinian people eat an average of 270 g of beef and beef derivatives per day. This means roughly a daily consumption of almost 1 g of CLA per day, possibly at levels of CLA which may exhibit beneficial health effects according to the literature. It can also be assumed that these minor amounts of CLA should balance the huge amount of dietary saturated fatty acids and cholesterol from beef and other sources of animal fat. As it can be seen, in Table 1, lean meat has a ratio which is double that of fatty meat.

Mechanism underlying the of action of CLA and saturated fats: CLA, Pro-oxidant or anti-oxidant?

Pioneering studies about the mechanisms involved in the antitumor potential of CLA stated that these fatty acids had strong antioxidant activities. In vitro research has suggested that CLA anticancer activity might be partially mediated by inducing lipid peroxidation [16].

The evidence supports the potential role of antioxidant agents in cancer prevention since they are scavengers for organic free radicals and so prevent the tissue damage. Although epidemiologic studies are not entirely consistent, many show an inverse relationship between dietary intake or blood levels of antioxidants contained in foods and cancer risk [17].

Dietary modifications of cattle forage. Influence of CLA, PUFAs and saturated fats levels on ruminant lipid tissues

The cis-9, trans-11 isomer is the principal dietary form of CLA, but the concentrations of this isomer and the trans-10, cis-12 isomer in dairy products or beef vary depending on the diet offered to cows or steers, respectively [18].

Decreasing the proportion of manipulated concentrates in the diet of steers, along with increased grass intake caused a desirable decrease in the concentration of intramuscular saturated fatty acid (SFA) and in the n-6 /n-3 PUFA ratio, together with an increase in the PUFA:SFA ratio and CLA concentration. The data indicate that intramuscular fatty acid composition of beef can be improved for healthy human nutrition by replacing manufactured food supplements by natural grass in the diet [19]. In non-ruminants, such as rodents, dietary CLA supplementation significantly reduced energy intake, growth rate, adipose depot weight and carcass lipid content independent of other dietary lipids. Overall, the reduction of adipose depot weight ranged from 43 to 88% [20].

Dietary fatty acid sources also affect CLA concentrations in milk from lactating cows. CLA concentration in milk fat can be enhanced by the addition of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) to the diet, especially oils high in 18:2 n-6 [21]. Diets rich in 18:3 n-3 can increase the CLA content in milk when dietary sources of this oil are accessible to the rumen microorganisms [22].

Experimental models

CLA behaves as a powerful anticarcinogen in a rat tumor model with an effective range as low as 0.5% in the diet. F344 rats were initiated with the carcinogen 2-amino-3-methylimidazol [4,5-f] quinolone (IQ) in order to induce colon carcinogenesis. CLA was administered to male rats by gavages followed by IQ. Aberrant crypt foci (ACF) were quantified in colon glands. While CLA administration had no impact on the size of ACF, their number was significantly reduced in the CLA group [23]. Interestingly, the protective effect of CLA is expressed at concentrations close to human consumption levels [24].

Other experimental evidence shows that dietary CLA inhibits azoxymethane-induced colonic aberrant crypt foci in male rats. The administration of CLA caused a significant reduction in the frequency of ACF. Also, these mixtures of trans isomers lowered the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) index in colonic ACF whereas apoptosis occurred in the cells of ACF [25]. Park et al reported that dietary CLA can inhibit 1.2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon carcinogenesis by a mechanism probably involving increased apoptosis. These authors suggested a possible chemopreventive activity of CLA in the early phase of colon tumorigenesis through modulation of cryptal cell proliferation activity and apoptosis [26]. As shown, the beneficial effects of CLA as antitumor food are observed for a broad range of chemical carcinogens.

In vitro assay

Several studies have demonstrated in vitro anticancer activity for CLA, with this being cytotoxic to human malignant melanoma, breast, lung and colorectal cancer cell lines [27]. The incubation with CLA showed a significant reduction in the proliferation of colorectal cell HT-29 compared to control cultures [28]. CLA has shown inhibitory effects in cellular growth suppression of human SW480 colon cancer cells and breast cancer MCF-7, being CLA preferentially incorporated into the phospholipid fraction of the MCF-7 cell lipids. The increase in lipid peroxidation observed in CLA-treated cells suggests that CLA may reverse the resistance to the oxidative stress characteristic of cancer cells.[29]

Clinical and epidemiological approaches

There is insufficient evidence from human epidemiological data to form a useful guide for nutritional recommendations. Very few of the animal studies have shown a dose-response relationship to the amount of CLA fed and the extent of tumor growth. Development of CRC has been suggested to be closely related to environmental exposure, especially that arising from the diet [30]. Experimental studies in animals and research on human beings have demonstrated that an increase of body fat mass is linked to increased risk of CRC. Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of cancer at a number of sites, including endometrium, postmenopausal breast cancer, pancreas, prostate and colon. There is strong evidence that a high risk of CRC is associated with obesity together other factors including and with a low intake of vegetables, whole grain cereals and fish [31]. It is also possible that one of the antitumoral effects adscribed to CLA may be linked to its capability of weight reduction.

Epidemiological studies suggest that whole milk and derived milk products, rich in CLA, fit well into a healthy eating pattern because CLA, besides its antitumor properties, is hypolipidaemic and antioxidative and is therefore an antiatherosclerotic nutrient [32].

Other anticarcinogens such as butyric acid, sphingomyelin, ether lipids and metabolites of tumor supressor lipids are also present in milk fat, and these may act in conjunction with CLA, thus making the consumption of whole milk and dairy derivatives beneficial [33].

Implications of the hypothesis

CLA-enriched milk fats may be used on a larger scale to produce CLA-enriched products, such as milk, butter, cheese and yoghurt. Consumption of such natural products may produce a natural chemopreventive effect, without the additional cost of oral supplements or the need for disturbing dietary changes [27, 34].

In conclusion, the challenge for nutritionists, physicians and dairy product producers is to improve the quality of healthy meat and milk derivatives, thereby obtaining lower levels of saturated fats and cholesterol, along with desirably higher levels of CLA and n-3 PUFAS. This task is challenging since taste and flavour must be maintained at acceptable levels.

References

De Lany JP, West DB: Changes in body composition with conjugated linoleic acid. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000, 19: 487S-493S.

Rudel LL: Atheroesclerosis and conjugated linoleic acid. B J Nutr. 1999, 81: 177-179.

Ha YL, Storkson J, Pariza MW: Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene-induced mouse forestomach neoplasia by conjugated dienoic derivarives of linoleic acid. Cancer Res. 1990, 50: 1097-101.

National Research Council (NRC) : Carcinogens and anticarcinogens in the human diet. 1996, National Academy Press, Washington DC

Navarro A, Osella AR, Muñoz SE, Lantieri MJ, Fabro EA, Eynard AR: Fatty acids, fibres and colorectal cancer risk in Córdoba, Argentina. J Epidemiol and Biostatistics. 1998, 3: 415-422.

Navarro A, Diaz M, Muñoz S, Lantieri Maria, Eynard AR: Characterization of meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in Cordoba, Argentina. Nutrition. 2003, 19: 7-10. 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00832-8

Crespi M: Models of screening program for colorectal cancer. Med Arch. 2002, 56: 47-49.

Navarro A, Muñoz SE, Eynard AR: Diet feeding habits and risk of colorectal cancer in Córdoba, Argentina. A pilot study. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1995, 14: 287-291.

Mc Lellan EA, Bird RP: Specificity study to evaluate induction of aberrant crypts in murine colons. Cancer Res. 1998, 48: 6183-6186.

Sesink AL, Termont DS, Kleibeuker JH, Van Der Meer: Red meat and colon cancer: dietary haem, but not fat, has cytotoxic and hyperproliferative effects on rat colonic epithelium. Carcinogenesis. 2000, 21: 1909-1915. 10.1093/carcin/21.10.1909

Eynard AR: Does chronic essential fatty acid deficiency (EFAD) constitute a pro-tumorigenic condition ?. Med Hypotheses. 1997, 48: 55-62.

Moloney AP, Mooney MT, Kerry JP, Troy DJ: Producing tender and flavoursome beef with enhanced nutritional characteristics. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001, 60: 221-229.

Mc Donald HB: Conjugated linoleic acids and disease prevention: a review of current knowledge. B J AM Coll Nutr. 2000, 19 (2 Suppl): 111S-118S.

Navarro A, Muñoz SE, Lantieri MJ, Fabro EA, Eynard AR: Composición de acidos grasos saturados e insaturados en alimentos de uso frecuente en Argentina. Archivos Lat de Nutr. 1997, 47: 276-281.

Ma DW, Wierzbicki AA, Field CJ, Clandinin MT: Conjugated linoleic acids in Canadian dairy and beef products. J Agric Food Chem. 1999, 47: 1956-1960. 10.1021/jf981002u

Kelly Gregory S: Conjugated linoleic acids: a review. J Alternative Med Rev. 2001, 6: 367-383.

Gonzales M, Riordan NH, Riordan HD: Antioxidants as chemopreventive agents for breast cancer. Biomedicina. 1998, 1: 120-127.

Pariza MW, Park Y, Cook ME: The biologically active isomers of conjugated linoleic acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2001, 40: 283-298. 10.1016/S0163-7827(01)00008-X

French P, Stanton C, Lawless F, O'Riordan EG, Monahan FJ, Caffrey PJ, Moloney AP: Fatty acid composition, including conjugated linoleic acid, of intramuscular fat from steers offered grazed grass, grass silage, or concentrate-based diets. J Anim Sci. 2000, 78: 2849-2855.

West DB, Delany JP, Camet PM, Blohm F, Truett AA, Scimeca J: Effects of conjugated linoleic acid on body fat and energy metabolism in the mouse. Am J Physiol. 1998, 275 (3Pt2): R667-672.

Kelly ML, Berry JR, Dwyer DA, Griinari JM, Chouinard PY, Van Amburgh ME, Bauman DE: Dietary fatty acid sources affect conjugated linoleic acid concentrations in milk from lactating dairy cows. J Nutr. 1998, 128: 881-885.

Dhiman TR, Satter LD, Pariza MW, Galli MP, Albright K, Tolosa MX: Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) content of milk from cows offered diets rich in linolenic acid. J Dairy Sci. 2000, 83: 1016-1027.

Liew C, Schut HA, Chin SF, Pariza MW, Dashwood RH: Protection of conjugated linoleic acid against 2-amino-3-methylimidazol [4, 5-f] quinolone-induced colon carcinogenesis in the F344 rat: a study of inhibitory mechanism. Carcinogenesis. 1995, 16: 3037-3043.

Ip C, Scimeca JA, Thompson H: Conjugated linoleic acid. A powerful anticarcinogen from animal fat sources. Cancer. 1994, 74 (3 Suppl): 1050-1054.

Kohno H, Suzuki R, Noguchi R, Hosokawa M, Miyashita K, Tanaka T: Dietary conjugated linoleic acid inhibits azoxymethane-induced colonic aberrant crypt foci in rats. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002, 93: 133-142.

Park HS, Ryu JH, Ha YL, Park JH: Dietary conjugated linoleic acid induces apoptosis of colonic mucosa in 1. 2-dimethylhydrazine-treated rats: a possible mechanism of the anticarcinogenic effect by CLA. Br J Nutr. 2001, 86 (5): 549-555.

Parodi PW: Cow's milk fat components as potential anticarcinogenic agents. J Nutr. 1997, 127: 1055-1060.

Shultz TD, Chew BP, Seaman WR, Luedecke LO: Inhibitory effect of conjugated dienoic derivates of linoleic acid and beta-carotene on the in vitro growth of human cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 1992, 15 (63): 125-133.

O'Shea M, Devery R, Lawless F, Murphy J, Stanton C: Milk fat conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) inhibits growth of human mammary MCF-7 cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20: 3591-3601.

Giovannucci E, Goldin B: The role of fat, fatty acids and total energy intake in the etiology of human colon cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997, 66: 1564-1571.

Hill MJ: Mechanisms of diet and colon carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999, Suppl 1: S95-98.

Pfeuffer M, Schrezenmeir J: Bioactive substances in milk with properties decreasing risk of cardiovascular disease. Br J Nutr. 2000, Suppl 1: S155-159.

Parodi PW: Cow's milk fat components as potential anticancinogenic agents. Am Soc Nutr Sci. 1997, 1055-1059.

Eynard AR: Potential of essential fatty acids as natural therapeutic products for human tumors. Nutrition. 2003, 19: 386-388. 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00956-5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Eynard, A.R., Lopez, C.B. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) versus saturated fats/cholesterol: their proportion in fatty and lean meats may affect the risk of developing colon cancer. Lipids Health Dis 2, 6 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-2-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-2-6