Abstract

Background

Duffy blood group polymorphisms are important in areas where Plasmodium vivax predominates, because this molecule acts as a receptor for this protozoan. In the present study, Duffy blood group genotyping in P. vivax malaria patients from four different Brazilian endemic areas is reported, exploring significant associations between blood group variants and susceptibility or resistance to malaria.

Methods

The P. vivax identification was determined by non-genotypic and genotypic screening tests. The Duffy blood group was genotyped by PCR/RFLP in 330 blood donors and 312 malaria patients from four Brazilian Amazon areas. In order to assess the variables significance and to obtain independence among the proportions, the Fisher's exact test was used.

Results

The data show a high frequency of the FYA/FYB genotype, followed by FYB/FYB, FYA/FYA, FYA/FYB-33 and FYB/FYB-33. Low frequencies were detected for the FYA/FYX, FYB/FYX, FYX/FYXand FYB-33/FYB-33 genotypes. Negative Duffy genotype (FYB-33/FYB-33) was found in both groups: individuals infected and non-infected (blood donors). No individual carried the FYX/FYB-33 genotype. Some of the Duffy genotypes frequencies showed significant differences between donors and malaria patients.

Conclusion

The obtained data suggest that individuals with the FYA/FYB genotype have higher susceptibility to malaria. The presence of the FYB-33 allele may be a selective advantage in the population, reducing the rate of infection by P. vivax in this region. Additional efforts may contribute to better elucidate the physiopathologic differences in this parasite/host relationship in regions endemic for P. vivax malaria, in particular the Brazilian Amazon region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plasmodium vivax has been the most common cause of the human malaria parasite in the Brazilian Amazon region over the last seven years [1]. Innate resistance to malaria infections in humans is conferred by different blood group polymorphisms. The association of the Duffy blood group (FY) with P. vivax human malaria has been well-documented, where Duffy-negative individuals are naturally resistant to invasion by this parasite [2].

The Duffy blood group antigen has been identified as a scavenger on the red blood cell (RBC) surface eliminating excesses of circulating toxic chemokines, named Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC) [3]. The determinant, a glycoprotein that passes through the membrane seven times, includes a 35–43 KDa epitope in the extracellular, N-terminal domain that mediates erythrocyte invasion by P. vivax merozoites [4]. The Fy gene has two exons (Fya and Fyb) that are encoded by the co-dominant alleles FYA and FYB, located on chromosome 1 [5, 6]. The corresponding anti-Fya and anti-Fyb antibodies define four different phenotypes; Fy(a+b+), Fy(a+b-), Fy(a-b+) and Fy(a-b-) [7]. The FYA and FYB alleles differ by a point mutation in the major cDNA transcript [8], encoding glycine in Fya or aspartic acid in Fyb at residue 42 of the most important form of the protein, encoded by the exon 2 [9, 8]. The molecular mechanism that gives rise to the null Duffy phenotype [Fy(a-b-)] has been classically associated with a point mutation in the GATA box of the DARC promoter which silences the gene encoding the Duffy system antigens in the RBCs of these individuals resulting in a FYB allele [9]. Recently, the FYA allele has been identified [10] and a new FYB allele was found with three single nucleotide polymorphisms (11). It has been demonstrated in blood donors from Southeast Brazil that Caucasians and African descendents were serologically Fy(b-) with the majority of the African descendents being FYB with the GATA single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), while the majority of Caucasian typing Fy(b-) had FYB with 265T/298A SNPs [11]. The Fy-negative is common on RBCs of Negro individuals from ethnic African groups, but it is rare in many other populations [12].

Previous studies have demonstrated that heterozygous Duffy negative malaria individuals remain susceptible to infections by P. vivax [13, 14]. It was demonstrated in individuals living in a malaria endemic region of Papua New Guinea that Duffy binding protein adherence to RBCs is significantly reduced for erythrocytes of P. vivax malaria patients who carry one Duffy-negative allele [15]. In addition, it was observed that in different areas from the Brazilian Amazon region some of the Duffy phenotypes showed significant correlation between blood donors and malaria patients [16]. On the other hand, a previous study in the Western Brazilian Amazon region (Rondônia State) did not correlate Fy heterozygosity with protection against P. vivax [17]. The present study reports the Duffy blood group genotyping in P. vivax malaria patients from four different Brazilian endemic areas, exploring these significant phenotypic associations between blood group variants, as well as polymorphic regions of RBC receptors, with susceptibility or resistance to malaria.

Methods

Study population

The study took place from May 2003 to August 2005. The vivax malaria patients (n = 312) who were enrolled in this study complied with the following criteria: they sought medical assistance presenting clinical malaria symptoms, were over 18 years old and had positive results for thick blood film/molecular diagnosis. A control group consisted of blood donors (n = 330) and according to the Brazilian blood bank policy they complied with the following criteria: they were over 18 years old, of both genders and belonging to all blood groups. Additionally, their place of birth was in the study area, they reported never suffering from malaria attacks and had no signs of malaria during the initial interview and had negative results for thick blood film/molecular diagnosis. The controls were matched to the patients in respect to age (± 5 years), gender and ethnicity. All of the control subjects were genetically independent. Blood samples were collected from all participants (Macapá/Amapá State, Belém/Pará State, Porto Velho/Rondônia State and Rio Branco/Acre State), after informed consent.

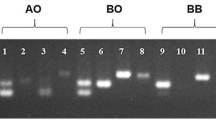

Genomic DNA extraction, PCR amplification and RFLP analysis

The Duffy blood group genotypes were assessed using PCR/RFLP with modifications as described previously [11]. Briefly, the DNA was extracted from frozen pellets of infected erythrocytes using the Easy-DNA™ extraction kit (Invitrogen, California – USA). The PCR was performed with 100 ng of DNA, 50 pmol of each primer, 2 nmol each dNTP, 1.0 U Taq DNA polymerase, and buffer, in a total volume of 50 μL. The promoter region was amplified using the FYN1 and FYN2 primers that flank the GATA box motif. To determine the Duffy RBC polymorphism, FYAB1 sense, and FYAB2 reverse sense primers were used [18]. The amplification conditions were performed as described by Castilho et al [11]. PCR products were run on 1.5% agarose gel, followed by ethidium bromide staining and photo-documentation using a Gel Doc 1000 (BioRad, Town, USA). The RFPL analysis was digested during three hours with Ban 1, Msp A1 and Sty 1 restriction enzymes as previously described [11].

Statistical analysis

In order to access the significance of the variables and to obtain independence among the proportions, the Fisher's exact test was used. The mean ages of patients and controls were 29 years (± 14 SD) and 28 years (± 8 SD), respectively. All the studied groups showed no statistically significant differences in mean ages or ethnicity, indicating well-matched populations. The same results were obtained when we compared the two different groups from each area.

Results

The genotypic and allelic frequencies of the Duffy blood group in the 330 blood donors and 312 patients infected by P. vivax as determined by PCR/RFLP are summarized in Table 1. The data show a high frequency of the FYA/FYB genotype in 199 individuals (31.0%) of the studied population. This is followed by 117 (18.2%) and 94 (14.6%) of homozygotes for the FYB and FYA alleles, respectively. While the frequencies for heterozygote individuals with FYA/FYB-33 and FYB/FYB-33 were comparable at 14.9% (96). Low frequencies were detected for the FYA/FYX, FYB/FYX, FYX/FYXand FYB-33/FYB-33 genotypes. The negative Duffy genotype (FYB-33/FYB-33) was found in both individuals infected by P. vivax and unaffected blood donors.

Table 2 shows a comparison of the results of genotyping and inferred phenotypes of FY among blood donors and patients infected by P. vivax in the Amazon region. In respect to the allelic combinations of FY, there was a significant difference between donors and patients only for the FYB-33/FYB-3 genotype (P = 0.0003). As for the heterozygotes, the results demonstrated a significant difference (P = 0.0404) between those with the FYA/FYB genotype, which was lower for blood donors (90 - 27.27%) than for patients infected by P. vivax (109 - 34.93%). No individuals were identified with the FYX/FYB-33 genotype.

The frequency of individuals with the FYB-33 allele among blood donors was 35.15% versus 24.36% in patients. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0033). The prevalence of the FYB allele was significantly higher (P = 0.0358) among malaria-infected patients. However, significant differences were not detected in respect to the frequency of individuals with the FYXand FYA alleles in the two study groups (Table 2).

Discussion

Thus far, innate resistance to malaria infections in humans has been attributed to blood group polymorphisms. Duffy blood group polymorphisms are important in areas where P. vivax predominates, because this molecule acts as a receptor for this protozoan (but not for the other human malaria parasites) on the surface of RBCs [19]. Field observations from West Africa and Ethiopia have indeed established a strong correlation between absence or low endemicity of P. vivax malaria and the high prevalence of the Duffy negative allele [20, 21]. Little is known on the frequency of RBC polymorphisms that confer either partial or complete resistance against malaria. The data obtained in the present study emphasize the importance of the evaluation of Duffy blood group genotypes in malaria endemic areas of the Brazilian Amazon region.

The Brazilian population has a highly heterogeneous ethnic composition, a result of the hybridization of the numerous native indigenous populations and immigrants from Europe, Africa and Asia. The immigration flow was not uniform in the different regions of the country [22–24]. The differential distribution of Duffy antigenic determinants among ethnic groups is an aspect characteristic of this blood system. Hence, this has been used as a marker for the ethnic composition as well as an indicator in the populational evolution. In the current study, significant differences in the allelic frequencies of the FY gene were identified when compared with previous studies of patients infected with human plasmodium in Brazilian Amazon regions [17, 25–27]. However, the FYA, FYB and FYB-33 alleles showed differential distributions compared to the population of the southeastern region of Brazil [11]. The genotypic compositions obtained in this study demonstrated significant variations compared to previous studies performed in the states of Pará and Rio Grande do Sul [28, 29] and in the cities of São Paulo [30], Campinas [11] and Ribeirão Preto [31] all of which are in the state of São Paulo, Southeastern region of Brazil.

The currently obtained results showed that the FYA/FYB genotype was the most common, followed by the homozygotes for the FYB and FYA alleles and by the heterozygotes FYA/FYB-33 and FYB/FYB-33 (Table 1). The FYB-33/FYB-33 genotype, which is classically seen in individuals unaffected by P. vivax infection, was identified in 3.2% of the general population and in 5.5% of blood donors. These numbers differ from previous reports on a group of malaria patients uninfected by P. vivax in the state of Rondônia [17], where the frequency of this genotype was 12% and also for a mixed sample from the Northern and Southeastern regions of Brazil [27]. Some populations had higher genotypic frequencies for FYA/FYB and FYB/FYB-33 than for a caucasian-like and negroid population from the Southeastern of Brazil [11]. On the other hand, the frequency of the FYB-33/FYB-33 genotype was lower. In fact, with the exception of negroid ethnic groups, this genotype is extremely rare [12, 30, 32, 33].

The FYA allele is common in European and Oriental peoples but it is rare in African Negroes. Additionally, the FYB is more common in populations classified as white than in asiatic and negroid populations [34, 35]. The frequency of the FYA and FYB alleles in the Brazilian Amazon population was higher than those in the Southeastern region [11] probably due to the massive influence of Portuguese colonization in the North region of Brazil as well as the presence of Amerindians [36], as recent molecular analysis has corroborated that Amerindians have an Asian origin [37]. Indeed, in the North region of Brazil, studies carried out with different tribes of Amerindians have shown that the FYA allele is the most common [31, 38]. As expected, a lower frequency of the FYB-33 allele was observed in the North region (P = 0.0001). Although a high prevalence of this allele was demonstrated in isolated communities in the states of Amapá and Pará, North region of Brazil [39], the introduction of a negroid ethnic component in the Amazon region is recent [40, 41]. In respect to the FYXallele, there does not seem to be a differential ethnic distribution as, the frequency detected here is similar to those described in other Caucasian-like populations in Brazil [11] and also in Europe [42].

The different FY allelic frequencies in individuals from North compared to Southeastern Brazil, may be due to the contribution of the three major ethnic groups (Europeans, in particular Portuguese; Blacks and Amerindians) in the formation of both populations. The Amerindian contribution was higher in the north of the country whereas European migration took place more in the South and Southeastern regions [43–45]. In spite of the current knowledge of the relationship between structure/function and tissue location of DARC, the functional significance of each of the alleles and the different genotypic combinations require further elucidation. The variation in the ethnic composition of the urban and rural populations of the Brazilian Amazon region and of distinct regions in Brazil [26, 46], may influence the allelic and genotypic distributions reflecting in matrixes of genetic mechanisms favorable to the susceptibility to infectious and parasitic diseases, in particular to malaria.

The frequency of the allele with the FY GATA mutation (FYB-33) was greater in blood donors than in patients infected with malaria (P = 0.0033), suggesting that there is a reduction in the infection rate of carriers of the FYB-33 allele. These results were recently reinforced by data from of individuals infected by P. falciparum when compared to those infected by P. vivax in Brazilian Amazon regions [27]. The FYB-33 allele is a variant of the FYB allele resulting from a T → C point mutation in the gene promoter region (neucleotide-33), which abolishes its expression [9]. The same occurs in the FYA allele, determining the FYAnullallele [10]. The presence of the FYB-33 allele results in a 50% reduction in the Duffy protein expression on the erythrocyte surface [15, 47]. This process demonstrates the action of the dose-related effect of the gene [15, 48], which may limit the invasion process of red blood cells by the parasite, although susceptibility to P. vivax may occur in heterozygotic Duffy-negative individuals [13, 14]. Thus the FY/FYB-33 genotypic combination, with either Fy(a+b-) or Fy(b+b-), seems to convey a reduction in the susceptibility to malaria. In vitro studies [15] support this hypothesis as RBCs that express these phenotypes have a significant reduction in cytoadherence of the parasite when compared to RBCs that express Fy(b+b+). Recently, in Papua New Guinea, a significant reduction in infection by P. vivax was observed in Duffy negative individuals heterozygotic for the FYAnullallele [49].

In this study a low frequency of the negative Duffy genotype (FYB-33/FYB-33) was detected among uninfected subjects. As has previously been demonstrated, the absence of the Fy antigen in many ethnic Negro groups and their descendents, does not seem to exert any deleterious effect, however it does bestow a natural resistance against infection by P. vivax [2, 9, 14, 35, 50, 51]. These individuals are homozygotes for the FYB mutation in the GATA, that completely abolishes the Fy expression in erythrocytes but not in cells of other tissues [9]. Recent reports have provided evidence on the transmission among Duffy-negative patients in Africa [52] and in Brazil [53]. These data suggest the possibility that P. vivax is utilizing alternative receptors, apart from Fy, for binding in the erythrocyte invasion process. Whether FYB carrying the GATA box mutation is the primordial gene that encodes the Duffy system antigens or whether the GATA box mutation has evolved to escape malaria infection per se is controversial. However, the presence of this allele (FYB-33) may be a demonstration of the selection advantage by mutation in the population. Thus, in the Brazilian Amazon, where P. vivax predominates, the frequency of the FYB-33 allele is higher than expected given the ethnic population, both in terms of heterozygotes and homozygotes. This might, over time, cause an increase in the number of Duffy-negative individuals in the population and, as a consequence, a reduction in the rate of infection by P. vivax in this region.

In the group of patients infected by P. vivax, different allelic combinations with FYXwere detected, including five (1.6%)FYA/FYXindividuals, four (1.3%) FYB/FYXand two (0.6%) FYX/FYX(Table 2). The frequency of this allele among patients and blood donors did not show statistical differences (P = 0.3873). Studies carried out in blood samples from European and American Caucasians and Afro-American individuals, demonstrated that the C265T (FYX) mutation altered the Duffy protein expression on the RBC surface differently, depending on the ethnic group, using at least two mechanisms. One mechanism involves silent transcription in one of the FYB alleles and the other affects the translation and/or the stability of the protein [47, 54]. These studies showed that heterozygote individuals for the FYX(FYWK) allele have 50% less of the Duffy protein on the surface of the membrane of the erythrocyte. On the other hand, individuals homozygotic for the FYXallele have about one tenth of the antigen expression in the erythrocytes [47]. However, the information shown by the present study suggest that these polymorphisms do not seem to be associated with susceptibility to malaria.

As illustrated in Table 2, a higher frequency of the FYA/FYB genotype in patients compared to blood donors (P = 0.0404) was detected. In principle, this seems to indicate that the condition of heterozygosis, resulting from the expression of the FYA and FYB genes, favors infection by P. vivax. In fact, as has already been demonstrated by us, based on a phenotyping study, Fy(a+b+) individuals may be more susceptible to infection by this species of Plasmodium [16]. Although no qualitative or quantitative measurements of the Duffy glycoprotein expressions were made in this study, we saw a larger number of malaria episodes among patients with the heterozygote genotype than the homozygote genotype. The basis of this observation has not been determined yet, but the phenotypic [16] and genotypic data presented from the same Brazilian Amazon areas associated with pertinent publications, point to the possibility that heterozygote individuals modulate the susceptibility to malaria by P. vivax by means of quantitative and/or qualitative variations that affect the Duffy antigen expression on erythrocytes. In the first aspect, in vitro studies demonstrate differences in the levels of the expression of FY glycoprotein on the surface of the reticulocytes of Caucasian-like and Afro-American individuals with the Fy(a+b+) erythrocytic phenotype [48]. These authors verified that individuals with FYA and FYB alleles expressed a lower quantity of DARC than heterozygotes. Hence, it is possible that heterozygote individuals have a greater repertory of receptors for the possible variations that occur in the parasite protein binder to the human erythrocytes.

The recent demonstration of polymorphisms in the Duffy binding protein in isolates of P. vivax from the Brazilian Amazon [55] seems to support the observed results. An association, between human receptor polymorphisms and variations in the parasite binders of Plasmodium falciparum that modulate susceptibility to malaria, was also demonstrated [19, 56–60]. Hence, apart from the different levels of the expression, the specific conformation of the Fya and Fyb antigens may determine differences in the susceptibility to infection. Nevertheless, one of the possible consequences of differential susceptibility to vivax malaria could be modifications in allelic frequencies of FYA and FYB in populations exposed to P. vivax, the most prevalent species in the Brazilian Amazon region. If in fact this process occurs as a consequence of infection, it seems to be necessary, but not sufficient to eliminate heterozygote individuals, even if they are affected by repetitive episodes of malaria by P. vivax, as the infection is rarely severe and occurs in the entire age range with different frequencies for different ages and regions of the Brazilian Amazon without lethality [61, 62].

Based on the significant associations described herein, our data differ from previous studies [17] carried out in the western Brazilian Amazon region as well as recent studies of patients from the Brazilian Amazon as a whole [27]. In respect to the first studies, these differences may be a result of the small sample sizes initially evaluated; the control group of the current study was composed of blood donors who reported never having experienced malaria against samples from individuals who had P. falciparum previously evaluated and the various ethnic groups in the different regions studied today (Eastern and Western Amazon). In relation to the recent studies, different to the findings observed in this study Brazilian Amazon population, the authors detected a significant association among infections by P. vivax and the FYB/FYB genotype, also conflicting with results of Wooley et al [48] in North American individuals (Caucasians and Afro-Americans). These divergences probably occurred due to the smaller sample size involved, and the fact that the control group consisted patients infected by P. falciparum.

Conclusion

The Brazilian population presents an elevated degree of miscegenation which is implicated in variations in the allelic distribution of FY, which was also found in this study. Future analyses that consider haplotypic frequencies of the alleles and quantification of the DARC expression in populational groups in endemic and non-endemic areas, increasing the knowledge on the dynamics of this gene and its possible contribution as a modulator in the susceptibility to malaria. The data obtained in the present study supports the hypothesis that individuals with the FYA/FYB genotype have higher susceptibility to malaria. The presence of the FYB-33 allele may be a selective advantage in the population, reducing the rate of infection by P. vivax in this region. However, the populational and longitudinal studies must be amplified accompanying groups of individuals with the FYB-33 allele and the FYA/FYB genotype, including clinical parameters, as well as the evaluation of their expressions which may contribute to better elucidate the physiopathologic differences in this parasite/host relationship in regions endemic for P. vivax malaria, in particular the Brazilian Amazon.

References

Kirchgatter K, Del Portillo HA: Clinical and molecular aspects of severe malaria. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2005, 77 (3): 455-475.

Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinnis MH: The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in Blacks: Duffy blood group genotype FYFY. N Engl J Med. 1976, 295: 302-304.

Darbonne WC, Rice GC, Mohler MA, Apple T, Gegert CA, Valente AJ, Baker JB: Red blood cells are a sink for interleukin 8, a leukocyte chemotaxin. J Clin Invest. 1991, 88: 1362-1369.

Chaudhuri A, Polyakova J, Zbrzezna V, Willians K, Gulati S, Pogo AO: Cloning of glycoprotein D cDNA, which encodes the major subunit of the Duffy group system and the receptor for the Plasmodium vivax malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 10793-10797. 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10793.

Donahue RP, Bias WB, Renwick JH, McKusick VA: Probable assignment of the Duffy blood group locus to chromosome 1 in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968, 61: 949-955. 10.1073/pnas.61.3.949.

Collins A, Keats BJ, Dracopoli N, Shields DC, Morton NE: Integration of gene maps: chromosome 1. Proc Natl Acad Science USA. 1992, 89: 4598-602. 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4598.

Parasol N, Reid M, Rios M, Castilho L, Harari I, Kosower S: A novel mutation in the coding sequence of the FY*B allele of the Duffy chemokine receptor gene is associate with na altered erythrocyte phenotype. Blood. 1998, 92: 2237-2243.

Mallinson G, Soo KS, Schall TJ, Pisacka M, Anstee DJ: Mutation in the erythrocyte chemokine receptor (Duffy) gene: the molecular basis of the Fya/Fyb antigens and identification of a deletion in the Duffy gene of an apparently healthy individual with the Fy(a-b-) phenotype. B J Hematol. 1995, 90: 823-829.

Tournamille C, Colin Y, Cartron JP, Kim CLV: Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individual. Nat Genet. 1995, 10: 224-228. 10.1038/ng0695-224.

Zimmerman PA, Woolley I, Masinde GL, Miller SM, McNamara DT, Hazlett F, Mgone CS, Alpers MP, Genton B, Kazura JW: Emergence of FY*Anullin a Plasmodium vivax-endemic region of Papua New Guinea. Med Sci. 1999, 96: 13973-13977.

Castilho L, Rios M, Pellegrino J, Saad STO, Costa FF, Reid MR: A novel Fy allele in Brazilians. Vox Sang. 2004, 87: 190-195. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2004.00554.x.

Race RR, Sanger R: Blood groups in man. 1975, Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 6

Miller LH, Mason SJ, Dvoak JA: Erythrocyte receptors for (Plasmodium knowlesi) malaria: Duffy blood group determinants. Science. 1975, 189: 561-562. 10.1126/science.1145213.

Miller LH, McAuliffe FM, Mason SJ: Erythrocyte receptor for malaria merozoites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977, 26: 204-208.

Michon P, Wooley I, Wood EM, Kastens W, Zimmerman PA, Adams JH: Duffy-null promoter heterozygosity reduces DARC expression and abrogates adhesion of the P. vivax ligand required for blood-stage infection. FEBS Lett. 2001, 495: 111-114. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02370-5.

Cavasini CE, Mattos LC, Alves RT, Couto AA, Calvosa VSP, Bonini Domingos CR, Rossit ARB, Machado RLD: Frequencies of ABO, MNSs and Duffy phenotypes among blood donors and malaria patients from four Brazilian Amazon areas. Hum Biol. 2006, 78: 255-259. 10.1353/hub.2006.0034.

Cavasini CE, Pereira FJT, Ribeiro WL, Wunderlich G, Ferreira MU: Duffy blood group genotypes among malaria patients in Rondônia, Western Brazilian Amazon. Rev Soc Bra Med Trop. 2001, 34 (6): 591-595.

Rios M, Cash K, Strupp A, Uehlinger J, Reid ME: DNA from urine sediment or buccal cells can be used for blood group molecular genotyping. Immunohematol. 1999, 15: 61-65.

Miller LH: Impact of malaria on genetic polymophism and genetic diseases in Afrincans and African Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91: 2415-2419. 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2415.

Welch SG, McGregor IA, Williams K: The Duffy blood group and malaria prevalence in Gambian West Africans. Trans R Soc Trop Med H. 1977, 71: 295-296. 10.1016/0035-9203(77)90102-X.

Mathews HM, Armstrong JC: Duffy Blood Types and vivax Malaria in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981, 30: 299-303.

Azevedo ES, Silva KM, Silva MC, Lima AM, Fortuna CM, Santos MG: Genetic and anthropological studies in the island of Itaparica, Bahia, Brazil. Hum Hered. 1981, 31 (6): 350-357.

Franco MHLP, Weimer TA, Salzano FM: Blood polymorphisms and racial admixture in two Brazilian populations. Am J Phys Anthrop. 1982, 58: 127-132. 10.1002/ajpa.1330580204.

Zago MA, Costa FF, Tone LG, Bottura C: Hereditary hemoglobin disorders in a Brazilian population. Hum Hered. 1983, 33: 125-129.

Camargo LMA, Moura MM, Engracia V, Pagotto RC, Basano SA, Pereira da Silva LH, Camargo EP, Beiguelman B, Krieger H: A Rural Community in a Brazilian Western Amazonian Region: Some Demographic and Epidemiological Patterns. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002, 97: 193-195. 10.1590/S0074-02762002000200008.

Ferreira RGM, Moura MM, Engracia V, Pagotto RC, Alves FP, Camargo LMA, Pereira da Silva LH, Camargo EP, Beiguelman B, Krieger H: Ethnic Admixture Composition of Two Western Amazonian Populations. Hum Biol. 2002, 74: 607-613. 10.1353/hub.2002.0041.

Souza TN, Sanchez BAM, Cerávolo IP, Carvalho LH, Brito CFA: Real-time multiplex allele-specific polymerqase chain reaction for genotyping of the Duffy antigen, the Plasmodium vivax invasion receptor. Vox Sang. 2007, 92 (4): 373-380.

Bortolini C, Weimer TA, Franco MH, Salzano FM, Layrisse Z, Schneider H, Schneider MP: Genetic studies in three South American black populations. Gene Geogr. 1992, 6: 1-16.

Dornelles CL, Callegari-Jacques SM, Robinson WM, Weimer TA, Franco MHLP, Hickmann AC, Geiger CJ, Salzano FM: Genetics, Surnames, Grandparents'Nationalities, and Ethnic Admixture in Southern Brazil – Do the Patterns of Variation Coincide?. Gen Mol Biol. 1999, 22: 151-161.

Novaretti MCZ, Dorlbiac-Llacer PE, Chamone DAF: Estudo de grupos sangüíneos em doadores de sangue caucasóides e negróides na cidade de São Paulo. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia. 2000, 22: 23-32. 10.1590/S1516-84842000000100004.

Stalote AC, Proto-Siqueira R, Da Silva WA, Zago MA, Palatnik M: The mutation G298A→Ala100Thr on the coding sequence of the Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor gene in non-caucasian Brazilians. Genet Mol Res. 2005, 4 (2): 166-173.

Mourant A, Kopec A, Domaniewska-Sobczak K: The Distribution of the Human Blood Groups and Other Polymorphisms. 1976, Oxford Press

Spencer HC, Miller LH, Collins WE, Knud-Hansen C, McGinnis MH, Shiroishi T, Lobos RA, Feldman RA: The Duffy blood group and resistance to Plasmodium vivax in Honduras. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978, 27: 664-670.

Lewis GE, Miller LH, Ibrahim L, Wong PW, McGinniss M, Ooi WL: Duffy phenotypes in Malaysian populations: correction of previous unusual findings. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988, 82: 509-510. 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90180-0.

Pogo AO, Chaudhuri A: The Duffy protein: A malarial and chemokine receptor. Semin Hemat. 2000, 37: 122-129. 10.1016/S0037-1963(00)90037-4.

Dos Santos SEB, Rodrigues JD, Ribeiro-dos-Santos AKC, Zago MA: Differential Contribution of Indigenous Men and Women to the Formation of an Urban Population in the Amazon Region as Revealed by mtDNA and Y-DNA. Am J Phy Anthrop. 1999, 109: 175-180. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199906)109:2<175::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-#.

Santos FR, Pandya A, Tyler-Smith C, Pena SD, Schanfield M, Leonard WR, Osipova L, Crawford MH, Mitchell RJ: The central Siberian origin for native American Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999, 64: 619-628. 10.1086/302242.

Salzano EM, Calegari-Jaques SM: South Amerindian Indians. A case study in evolution. 1988, Clarendon Press Oxford, UK

Perna SJQ, Cardoso GL, Guerreiro JF: Duffy blood group gentypes among African-Brazilian communities of the Amazon region. Genet Mol Res. 2007, 6: 166-172.

Alves-Silva J, Santos MS, Guimarães PEM, Ferreira ACS, Bandelt H-J, Pena SDJ, Prado VF: The Ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA Lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2000, 67: 444-461. 10.1086/303004.

Calegari-Jacques SM, Grattapaglia D, Salzano FM: Historical Genetics: Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Formation of the Brazilian Population. Am J Hum Biol. 2003, 15: 824-834. 10.1002/ajhb.10217.

Ansart-Pirenne H, Martin-Blanc S, Le Pennec P-Y, Rouger P, Cartron J-P, Tournamille C: FY*X real-time polymerase chain reaction with melting curve analysis associated with a complete one-step real-time FY genotyping. Vox Sang. 2007, 92: 142-147. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00872.x.

Santos SEB, Guerreiro JF: The indigenous contribution to the formation of the population of the Brazilian Amazon region. Revista Brasileira de Genética. 1995, 2: 311-315.

Santos EJM, Ribeiro-dos-Santos ÂKC, Guerreiro JF, Aguiar GFS, Santos SEB: Migration and ethnic change in an admixed population from the Amazon region (Santarém, Pará). Revista Brasileira de Genética. 1996, 3: 511-515.

Carvalho-Silva DR, Santos FR, Rocha J, Pena SD: The phylogeography of Brazilian Y-chromosome lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2001, 68: 281-286. 10.1086/316931.

Santos SEB, Ribeiro dos Santos AKC, Santos EJM, Guerreiro JF: The Amazonian microcosm. Ciênc Cult. 1999, 51: 181-190.

Yazdanbakhsh M, Rios M, Storry JR, Kosower N, Parasol N, Chaudhuri A, Reid ME: Molecular mechanisms that lead to reduced expression of Duffy antigens. Transf. 2000, 40: 310-320. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40030310.x.

Woolley IJ, Hotmire KA, Sramkoski RM, Zimmerman PA, Kazura JW: Differential expression of the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines according to RBC age and FY genotype. Transf. 2000, 40: 949-953. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40080949.x.

Kasehagem LJ, Mueller I, Kiniboro B, Bockarie MJ, Reeder JC, Kazura JW, Kastens W, McNamara DT, King CH, Whalen CC, Zimmerman PA: Reduced Plasmodium vivax Erythrocyte Infection in PNG Duffy-Negative Heterozygote. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2: 336-10.1371/journal.pone.0000336.

Livinstone FB: The Duffy blood groups, vivax malaria, and malaria selection in human populations: a review. Hum Biol. 1984, 56: 413-425.

Hadley TJ, Peiper C: From malaria to chemokine receptor: The emerging physiologic role of the Duffy blood group antigen. Blood. 1997, 89: 3077-3091.

Ryan JR, Stoute JA, Amon J, Duntons RF, Mtalib R, Koros J, Owour B, Luckhart S, Wirtz RA, Barnwell JW, Rosenberg R: Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a Duffy antigen negative population in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 75: 775-581.

Cavasini CE, Mattos LC, Couto AA, Bonini-Domingos CR, Valencia SH, Neiras WC, Alves TA, Rossit ARB, Castilho L, Machado RLD: Plasmodium vivax infection among Duffy antigen-negative individuals from de Brazilian Amazon region: an exception?. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 101: 1042-1044. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.011.

Tournamille C, Kim CLV, Gane P, Pennec PYL, Roubinet F, Babinet J, Carton JP, Colin Y: Arg89Cys substitution results in very low membrane expression of the Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines in Fy* individuals. Blood. 1998, 92: 2147-2156.

Souza TN, Cerávolo IP, Fontes CJF, Couto A, Carvalho LH, Brito CFA: The pattern of major polymorphisms in the Duffy binding protein ligand domain among Plasmodium vivax isolates from the Brazilian Amazon area. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006, 146: 251-254. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.11.006.

Lell B, May J, Schmidt-Ott RJ, Lehman LG, Luckner D, Greve B, Matousek P, Schmid D, Herbich K, Mockenhaupt FP, Meyer CG, Bienzle U, Kremsner PG: The Role of Red Blood Cell Polymorphisms in Resistance and Susceptibility to Malaria. Clin Infec Dis. 1999, 28: 794-799. 10.1086/515193.

Moulds JM, Moulds JJ: Blood Group Associations With Parasites, Bacteria, and Viruses. Transf Med Rev. 2000, 14: 302-311. 10.1053/tmrv.2000.16227.

Carter R, Mendis KN: Evolutionary and Historical Aspects of the Burden of Malaria. Clin Microb Rev. 2002, 15: 564-594. 10.1128/CMR.15.4.564-594.2002.

Zimmerman PA, Patel SS, Maier AG, Bockarie MJ, Kazura JW: Erythrocyte polymorphisms and malaria parasite invasion in Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003, 19: 250-252. 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00112-0.

Chung WY, Gardiner DL, Hyland C, Gatton M, Kemp DJ, Trenholme KR: Enhanced invasion of blood group A1 erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005, 144: 128-130. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.08.004.

Alves FP, Durlacher RR, Menezes MJ, Krieger H, Pereira da Silva LH, Camargo EP: High prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections in native Amazonian population. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 66: 641-648.

Beiguelman B, Alves FP, Moura MM, Engracia V, Nunes ACS, Heckmann MIO, Ferreira RGM, Pereirara da Silva LH, Camargo EP, Krieger H: The Association of Genetic Markers and Malaria Infection in the Brazilian Western Amazonian Region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003, 98: 455-460. 10.1590/S0074-02762003000400004.

Acknowledgements

To all individuals enrolled in this study and to Blood Bank Managing Director of the studied areas for help in blood donor samples collection. We thank Aline Barroso, Maria Cristina Figueredo and Mauro Tada for help in malaria field work. To Professor Luiz Hildebrando Pereira da Silva for facilities at CEPEM. Financial support was provided by FAPESP (Process 02/9546-1), CNPq (Process 302353/2003-8). C.E.C. is a PhD student from Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto. The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Research Board of the Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

CEC carried out all genotype assay. AADC, VSDC and CEC collected samples from P. vivax malaria individuals and blood donors. CEC, LCM, CRBD and LC participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. RLM and ARBR conceived of the study and participated in all aspects of its design, acquisition of funding, execution, coordination and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavasini, C.E., de Mattos, L.C., Couto, Á.A.D. et al. Duffy blood group gene polymorphisms among malaria vivax patients in four areas of the Brazilian Amazon region. Malar J 6, 167 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-6-167

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-6-167