Abstract

Background

The stress associated with residency training may place house officers at risk for poorer health. We sought to determine the level of self-reported health among resident physicians and to ascertain factors that are associated with their reported health.

Methods

A questionnaire was administered to house officers in 4 residency programs at a large Midwestern medical center. Self-rated health was determined by using a health rating scale (ranging from 0 = death to 100 = perfect health) and a Likert scale (ranging from "poor" health to "excellent" health). Independent variables included demographics, residency program type, post-graduate year level, current rotation, depressive symptoms, religious affiliation, religiosity, religious coping, and spirituality.

Results

We collected data from 227 subjects (92% response rate). The overall mean (SD) health rating score was 87 (10; range, 40–100), with only 4 (2%) subjects reporting a score of 100; on the Likert scale, only 88 (39%) reported excellent health. Lower health rating scores were significantly associated (P < 0.05) with internal medicine residency program, post-graduate year level, depressive symptoms, and poorer spiritual well-being. In multivariable analyses, lower health rating scores were associated with internal medicine residency program, depressive symptoms, and poorer spiritual well-being.

Conclusion

Residents' self-rated health was poorer than might be expected in a cohort of relatively young physicians and was related to program type, depressive symptoms, and spiritual well-being. Future studies should examine whether treating depressive symptoms and attending to spiritual needs can improve the overall health and well-being of primary care house officers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although physicians generally undergo residency training when they are in their physical prime, residency is physically and emotionally demanding. [1–17] A number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies over the past decades have examined the negative impact of residency training on fatigue level, [1, 14, 16, 17] stress, [1–13, 15] and even physiologic measures (e.g., blood pressure and heart rate) [2] in resident physicians. In a recent review, levels of burnout among house officers were found to be high, [18] with the potential to adversely impact patient care. Residency training may also adversely impact the self-health care practices (e.g., consuming too much alcohol or working through acute illness) [19, 20] and self-perceived health of house officers. [19–21] Previous investigations have reported that the health risk during training may vary based on certain demographic factors [3, 13] and residency-related characteristics (e.g., program type and post-graduate year). [3, 9, 10, 12, 13]

Certain other personal characteristics, such as religiosity and spirituality, have been related to psychological and physical health. [22, 23] Although there continues to be ongoing discussions over their respective definitions, the terms "religion" and "religiosity" have been used more recently to describe formal and institutional expressions of faith [22, 24] whereas "spirituality" has been used to describe an individual's sense of coherence and connectedness to the truth or the divine. [22, 24] The salutary effects of spirituality/religion on physical health have been proposed to work through a number of mechanisms, including beneficial physiologic mechanisms (e.g., lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol level) [25] and health promoting behaviors. [25] Spirituality and religion may also strengthen coping mechanisms against the negative long-term effects of stress by establishing a sense of meaning in life [23] and increasing involvement in social networks. [23] A previous study showed potentially beneficial health effects of certain religious characteristics on young doctors' long-term health outcomes. [26] However, the effects of spirituality/religion on health may not always be salutary. [25, 27] Spirituality/religion, then, may be one factor, along with other psychosocial and residency-related factors, related to the self-rated health of house officers. [28–34] We therefore investigated the self-rated health of a contemporaneous group of house staff in 4 different primary care residency programs, and examined factors related to their health. We hypothesized that distinct dimensions of religion, religiosity, and spirituality may have salutary effects on residents' overall self-rated health, [25, 26] and thus may serve as potential targets for intervention.

Our specific objectives were: 1) to assess how primary care house officers rate their own health; and 2) to assess how self-rated health is related to demographic and residency characteristics, mood, and specific dimensions of spirituality and religiosity.

Methods

Study Participants

Between July 2003 and November 2003, we recruited house officers from 4 primary care residency-training programs [35] at the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Centers in Cincinnati, OH: internal medicine, pediatrics, combined internal medicine-pediatrics, and family medicine. We administered a questionnaire during each program's annual In-Training Exam; all participating house officers were excused from overnight call duties on the night prior to the exam. The respondents' identities were kept completely anonymous and participation was voluntary. For completing the survey, house officers received a free lunch and a $5 gift certificate to a local coffee shop. The institutional review boards at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved the study.

Instruments

Outcome Measure

We assessed house officers' current self-reported overall health by using a rating scale with a range of 0 (labeled "death") to 100 (labeled "perfect health"). [36, 37] We also asked a single question about their general health: "In general, would you say that your health has been Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, or Poor." [36]

Independent Measures

Residents' Demographic and Residency Characteristics

We assessed house officers' demographic and residency-related characteristics. Specifically, we asked questions regarding age, sex, race/ethnicity, post-graduate year level, program type (pediatrics, internal medicine, combined internal medicine-pediatrics, or family medicine), and current rotation (inpatient ward/intensive care unit versus non-inpatient-based rotation). We assumed that all house staff physicians had similar education levels and incomes, so we did not ask about education and income.

Residents' Mood

Depressive symptoms were measured by using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD-10). [38, 39] The CESD-10 has been used extensively in a number of general and chronically ill populations and asks the subject to respond to 10 statements as they have pertained to themselves during the past week. Scores on each item are summed (range 0–30), with higher scores representing greater levels of depressive symptoms.

Residents' Religious Affiliation, Religiosity, and Spirituality

We first asked a question modeled after the religious preference question used in Gallup surveys, "What is your religious affiliation?" [40] We then administered the 5-item Duke Religion Index [41] to measure 3 dimensions of religious activity: organized religious activity (scored from 1–6, with higher scores indicating more frequent activity), non-organized religious activity (scored from 1–6, with higher scores indicating more frequent activity), and intrinsic religiosity (subjective views on religion and religious experience; scored from 3–15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of intrinsic religiosity). We used an adapted 10-item version of the Brief RCOPE [42] (modified with the aid of K. Pargament, PhD, the developer of the instrument) to assess the positive and negative roles of religion in coping with the stresses of residency training (in lieu of coping with chronic illness). Positive religious coping mechanisms (e.g., collaborative religious coping, benevolent religious reappraisals) are scored from 6–24, with higher scores indicating greater use of positive religious coping mechanisms, and negative religious coping mechanisms (e.g., feelings of spiritual abandonment) are scored from 4–16, with higher scores indicating more frequent use of negative religious coping mechanisms. We also used 3 subscales from the full RCOPE to assess interpersonal religious discontent (scored from 3–12, with higher scores indicating greater discontent with clergy/religious institutions), religious support seeking (scored from 5–20, with higher scores indicating greater levels of seeking support from clergy or members of the congregation), and spiritual support seeking (scored from 4–16, with higher scores indicating greater levels of seeking support from or connecting with a higher power). We measured spiritual well-being by using the 23-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being-Expanded (FACIT-SpEx) scale, [43] which assesses faith (comfort and strength in one's beliefs) and meaning/peace (sense of meaning, purpose, and peacefulness in life). The FACIT-SpEx is scored from 0–92, with higher scores indicating greater overall spiritual well-being.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, medians, and 25th and 75th percentiles. Due to relatively small numbers of subjects in specific minority groups, we dichotomized race as Caucasian versus non-Caucasian. We categorized religious affiliations into Christian, Jewish, Other, and None/Undesignated for our analyses. Univariate analyses included χ2 tests to compare proportions and Spearman's correlation coefficients, Student's t-tests, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate, for continuous variables.

We conducted a multivariable analysis in which independent variables associated with health rating scores at a P < 0.20 level in univariate analyses were entered into a backward elimination linear regression model. Variables associated with health ratings at a P < 0.05 level in the backward elimination were retained in the final model. Due to the relatively skewed nature of the health rating scores, we examined our final multivariable model using log transformed health rating scores. We found no significant change in the relationship between the outcome and independent variables, so we report the non-transformed results. Regression diagnostics were examined for multicollinearity and no problems with multicollinearity were found. All analyses were performed by using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Of a total of 247 house officers in the 4 primary care training programs, 227 subjects completed the questionnaires (92% response rate). Their mean (SD) age was 28.7 (3.8) years; 131 (58%) were female; 167 (74%) were white; 165 (73%) were Christian; and 112 (49%) were pediatric residents, 62 (27%) were internal medicine residents, 26 (12%) were combined internal medicine-pediatric residents, and 27 (12%) were family medicine residents (Table 1).

The overall mean (SD) health rating score was 87 (10; range, 40–100; Figure 1) and the median (25th, 75th percentile) score was 90 (80, 93). Only 4 (2%) house officers rated their health as perfect. On the Likert scale, 88 (39%) stated their health was "excellent," 98 (44%) said "very good," 29 (13%) said "good," and 10 (4%) said "fair." No respondents stated that their health was "poor."

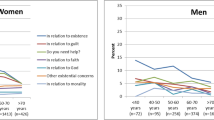

In univariate analyses, residents' health rating scores were significantly related to their post-graduate year level, although there was no particular pattern. Health rating scores were also related to residency program type, with internal medicine house officers having mean scores that were 7–8 points lower than those of other house officers (Table 1). Twenty-two (37%) of internal medicine residents reported only fair or good general health (Figure 2). Greater levels of depressive symptoms (r = -0.30) and poorer spiritual well-being (r = 0.25) were associated with lower health rating scores (Table 2).

In multivariable analyses, lower health rating scores were associated with internal medicine program type, greater levels of depressive symptoms, and poorer spiritual well-being (Table 3). Residents in the internal medicine residency program reported significantly lower scores than pediatric and combined internal medicine-pediatric residents and internal medicine residents' scores trended lower when compared with those of family medicine residents (P = 0.052; parameter estimate = 4.43). The R2 for the multivariable model was 0.14.

Discussion

Because resident physicians are generally young and highly educated health professionals, they might be expected to report being in excellent health, especially in the context of the patients they take care of. Nevertheless, residency training is a period in which physicians deal with high levels of chronic fatigue, stress, and burnout, [18] which potentially may adversely affect the clinical care they provide.

As such, we sought to determine how residents rate their health and which factors are associated with their self-rated health. Our first finding was that self-perceived health was worse than anticipated: the mean (SD) health rating on the 0–100 scale was 87 (10), only 4 (2%) rated their health at 100, and on the Likert scale, only 39% considered their health to be excellent. In comparison, the mean (SD) health rating of adult patients with HIV was 80 (17), [36] and a representative general population sample of adults in the United Kingdom – 42% of whom reported a moderate problem in at least one dimension of their functional health – had a mean health rating of 83 (17). [37] Some previous studies had shown that women report poorer functioning than men during their training period [44] whereas other studies did not find such between-sex differences. [9, 18] In our study, men and women had nearly identical health rating scores. We also found that internal medicine residents had significantly lower health ratings than pediatric and combined internal medicine-pediatric residents, and borderline-lower scores than family medicine residents (P = 0.052). On the general health question, over one-third of internal medicine residents reported that their health was only fair or good, which was about double the proportion in family medicine and internal medicine-pediatric residents, and about 6 times as great as for categorical pediatric residents (Figure 2).

Depressive symptoms were also significantly related to lower health rating scores. The correlation between psychological health and other health parameters has been described in other populations. However, depressive symptoms and other significant independent variables only accounted for a fraction of the variance in health rating scores (R2 = 0.14). Other factors that we did not measure, such as subjects' personality characteristics, may have played a part in our findings. A recent review, however, found no strong associations between house officers' personality traits and risk for problems during residency training. [18] Although we wished to minimize the impact of acute sleep- and stress-related fatigue by administering the questionnaire during the In-Training Exam (no residents were on call the previous night), our findings may have been confounded by the chronic fatigue of residency. Also, we did not ask about acute illnesses (e.g., viral infections) that may have affected health ratings. Lastly, residency characteristics; lack of time for exercise, leisure activities, and health-promoting behaviors; and perceptions surrounding support from residency personnel (e.g., house staff peers, administrative personnel, faculty) may also have played a role in residents' health ratings.

We also found that certain aspects of spirituality are related to health ratings, even after controlling for mood. In multivariable analyses, those who reported poorer spiritual well-being were more likely to have poorer overall health ratings. House officers' sense of broader meaning and of connectedness may serve to buffer against the stresses and feelings of depersonalization associated with residency training, and thereby have salutary effects on perceptions of overall health. Nevertheless, religion and religiosity variables were not associated with self-rated overall health in univariate or multivariable analyses. Thus, neither the institutional/formal aspects of religion nor one's personal religious activities and religious coping mechanisms appear to influence perceptions of overall health among resident physicians. We speculate that some house officers may experience comfort and greater resilience through formal and more personal religious traditions, which may in turn positively impact their perceptions of well-being, but that time constraints and depersonalizing effects of residency training (e.g., seeing people die) may disengage others from religion. There is growing interest in teaching medical trainees [45, 46] to incorporate religion and spirituality into the physician-patient relationship. However, how young physicians' own spiritual and religious needs may or may not be met in the context of their medical training has not been studied as well.

Our investigation had several limitations. The cross-sectional and non-experimental study design precludes determining causality between the significant independent factors and health rating scores. Also, we did not account for acute illnesses, such as viral infections, which may have influenced results. Lastly, although our sample was large and our response rate was high, the generalizability of our findings to other centers is uncertain.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the self-rated health of resident physicians appears to be lower than might be expected in a presumably healthy cohort of young physicians. Self-rated health was lower for residents in internal medicine and those with a greater level of depressive symptoms and a lower level of spiritual well-being. Further work to evaluate potential resident subgroups who may benefit from interventions to improve physical, psychosocial, and spiritual/religious well-being are warranted and should also assess if such interventions have the potential to impact clinical care.

References

Kash KM, Holland JC, Breitbart W, Berenson S, Dougherty J, Ouellette-Kobasa S, Lesko L: Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology (Williston Park). 2000, 14 (11): 1621-1633.

Butterfield PS: The stress of residency. A review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1988, 148 (6): 1428-1435. 10.1001/archinte.148.6.1428.

Hsu K, Marshall V: Prevalence of depression and distress in a large sample of Canadian residents, interns, and fellows. Am J Psychiatry. 1987, 144 (12): 1561-1566.

Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA: Variation of mood and empathy during internship. JAMA. 2002, 287 (23): 3143-3146. 10.1001/jama.287.23.3143.

Schneider SE, Phillips WM: Depression and anxiety in medical, surgical, and pediatric interns. Psychol Rep. 1993, 72 (3 Pt 2): 1145-1146.

Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O: The impact of job stress and working conditions on mental health problems among junior house officers. A nationwide Norwegian prospective cohort study. Med Educ. 2000, 34 (5): 374-384. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00540.x.

Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O: Suicidal ideation among medical students and young physicians: a nationwide and prospective study of prevalence and predictors. J Affect Disord. 2001, 64 (1): 69-79. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00205-6.

Kirsling RA, Kochar MS, Chan CH: An evaluation of mood states among first-year residents. Psychol Rep. 1989, 65 (2): 355-366.

Archer LR, Keever RR, Gordon RA, Archer RP: The relationship between residents' characteristics, their stress experiences, and their psychosocial adjustment at one medical school. Acad Med. 1991, 66 (5): 301-303. 10.1097/00001888-199105000-00018.

Girard DE, Hickam DH, Gordon GH, Robison RO: A prospective study of internal medicine residents' emotions and attitudes throughout their training. Acad Med. 1991, 66 (2): 111-114. 10.1097/00001888-199102000-00014.

Hendrie HC, Clair DK, Brittain HM, Fadul PE: A study of anxiety/depressive symptoms of medical students, house staff, and their spouses/partners. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990, 178 (3): 204-207. 10.1097/00005053-199003000-00009.

Reuben DB: Depressive symptoms in medical house officers. Effects of level of training and work rotation. Arch Intern Med. 1985, 145 (2): 286-288. 10.1001/archinte.145.2.286.

Tyssen R, Vaglum P: Mental health problems among young doctors: an updated review of prospective studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002, 10 (3): 154-165. 10.1080/10673220216218.

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL: Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002, 136 (5): 358-367.

Michels PJ, Probst JC, Godenick MT, Palesch Y: Anxiety and anger among family practice residents: a South Carolina family practice research consortium study. Acad Med. 2003, 78 (1): 69-79. 10.1097/00001888-200301000-00013.

Leung L, Becker CE: Sleep deprivation and house staff performance. Update 1984–1991. J Occup Med. 1992, 34 (12): 1153-1160.

Samkoff JS, Jacques CH: A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991, 66 (11): 687-693. 10.1097/00001888-199111000-00013.

Thomas NK: Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004, 292 (23): 2880-2889. 10.1001/jama.292.23.2880.

Baldwin PJ, Dodd M, Wrate RM: Young doctors' health–II. Health and health behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1997, 45 (1): 41-44. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00307-3.

Baldwin PJ, Dodd M, Wrate RW: Young doctors' health–I. How do working conditions affect attitudes, health and performance?. Soc Sci Med. 1997, 45 (1): 35-40. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00306-1.

Rosen IM, Christie JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA: Health and health care among housestaff in four US internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000, 15 (2): 116-121. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.11218.x.

Hill PC, Pargament KI: Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality. Implications for physical and mental health research. Am Psychol. 2003, 58 (1): 64-74. 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.64.

George LK, Larson DB, Koenig HG, McCullough ME: Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2000, 19 (1): 102-116.

Hill PC, Pargament KI, Hood RW, McCullough ME, Swyers JP, Larson DB, Zinnbauer BJ: Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. J Theory Soc Behav. 2000, 30 (1): 51-77. 10.1111/1468-5914.00119.

Seybold KS, Hill PC: The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001, 10 (1): 21-24. 10.1111/1467-8721.00106.

Moore RD, Mead L, Pearson TA: Youthful precursors of alcohol abuse in physicians. Am J Med. 1990, 88 (4): 332-336. 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90485-V.

Larson DB, Sherrill KA, Lyons JS, Craigie FC, Thielman SB, Greenwold MA, Larson SS: Associations between dimensions of religious commitment and mental health reported in the American Journal of Psychiatry and Archives of General Psychiatry: 1978-1989. Am J Psychiatry. 1992, 149 (4): 557-559.

Mills PJ: Spirituality, religiousness, and health: From research to clinical practice. Ann Behav Med. 2002, 24 (1): 1-2. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_01.

Ayele H, Mulligan T, Gheorghiu S, Reyes-Ortiz C: Religious activity improves life satisfaction for some physicians and older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47: 453-455.

Meraviglia MG: The effects of spirituality on well-being of people with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004, 31 (1): 89-94.

Rossman ML: Should a doctor ask about a patient's spiritual beliefs?. Adv Mind Body Med. 2001, 17 (2): 101-103.

Harris WS, Gowda M, Kolb JW, Strychacz CP, Vacek JL, Jones PG, Forker A, O'Keefe JH, McCallister BD: A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Arch Intern Med. 1999, 159 (19): 2273-2278. 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2273.

Daaleman TP, Perera S, Studenski SA: Religion, spirituality, and health status in geriatric outpatients. Ann Fam Med. 2004, 2 (1): 49-53. 10.1370/afm.20.

Yi MS, Luckhaupt SE, Mrus JM, Mueller CV, Peterman AH, Puchalski CM, Tsevat J: Religion, spirituality, and depressive symptoms in primary care house officers. Ambul Pediatr. 2006, 6 (2): 84-90. 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.10.002.

Primary Care Loan Program for Allopathic and Osteopathic Medical Students at. Accessed 12/17/04., [http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/dsa/pages/pcl.htm]

Mrus JM, Schackman BR, Wu AW, Freedberg KA, Tsevat J, Yi MS, Zackin R: Variations in Self-Rated Health Among Patients with HIV Infection. Qual Life Res. 2006, 15 (3): 503-514. 10.1007/s11136-005-1946-4.

Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, Williams A: Variations in population health status: results from a United Kingdom national questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998, 316 (7133): 736-741.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL: Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994, 10 (2): 77-84.

Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, Rollman BL, McGinnis KA, Rabeneck L, Weissman S, Smola S, Schultz R, Whittle J, Rodriguez-Barradas M: Clinical importance of HIV and depressive symptoms among veterans with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2002, 17 (7): 512-520. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10803.x.

Gallup G, Gallup GH: The Gallup poll: public opinion 1995. 1996, Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Inc

Koenig H, Parkerson GR, Meador KG: Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry. 1997, 154 (6): 885-886.

Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L: Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998, 37 (4): 710-724. 10.2307/1388152.

Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D: Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002, 24 (1): 49-58. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06.

Elliot DL, Girard DE: Gender and the emotional impact of internship. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1986, 41 (2): 54-56.

Puchalski CM, Larson DB, Lu FG: Spirituality courses in psychiatry residency programs. Psychiatr Ann. 2000, 30 (8): 543-548.

Armbruster CA, Chibnall JT, Legett S: Pediatrician beliefs about spirituality and religion in medicine: associations with clinical practice. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: e227-e235. 10.1542/peds.111.3.e227.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/7/9/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Kenneth Pargament, PhD, for helping to adapt the Brief RCOPE. We also thank Mona Ho, MS, and Richard Hornung, DrPH, for their statistical input. Previous Presentation: This investigation was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine annual meeting, Chicago, IL, 2004.

Funding/support: This study was funded by National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grant # K24 AT001676 (PI: Tsevat). Dr. Yi is supported by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Career Development Award (K23 HD046690). Dr. Mrus was a recipient of a Career Development Award (RCD 01011) from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr. Puchalski is the Founder and Director of The George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health (GWish). GWish's stated mission is to work "toward a more compassionate system of healthcare by restoring the heart and humanity of medicine through research, education, and policy work focused on bringing increased attention to the spiritual needs of patients, families, and the healthcare professionals."

Authors' contributions

MY, CM, SL, AP, CP, and JT participated in the conception and design of the study. MY, CM, and SL participated in the acquisition of data. MY, JM, SL, and JT participated in the analysis (see acknowledgements) and interpretation of data. MY, JM, and JT participated in the drafting of the manuscript. MY, JM, CM, SL, AP, CP, and JT participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MY, JM, SL, and JT provided administrative, technical, or material support. MY, JM, and JT provided study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, M.S., Mrus, J.M., Mueller, C.V. et al. Self-rated health of primary care house officers and its relationship to psychological and spiritual well-being. BMC Med Educ 7, 9 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-9