Abstract

Background

To characterize whether medical comorbidities, depression and anxiety predict patient-reported functional improvement after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods

We analyzed the prospectively collected data from the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry for patients who underwent primary or revision TKA between 1993–2005. Using multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analyses, we examined whether medical comorbidities, depression and anxiety were associated with patient-reported subjective improvement in knee function 2- or 5-years after primary or revision TKA. Odds ratios (OR), along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-value are presented.

Results

We studied 7,139 primary TKAs at 2- and 4,234 at 5-years; and, 1,533 revision TKAs at 2-years and 881 at 5-years. In multivariable-adjusted analyses, we found that depression was associated with significantly lower odds of 0.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3 to 0.9; p = 0.02) of ‘much better’ knee functional status (relative to same or worse status) 2 years after primary TKA. Higher Deyo-Charlson index was significantly associated with lower odds of 0.5 (95% CI: 0.2 to 1.0; p = 0.05) of ‘much better’ knee functional status after revision TKA for every 5-point increase in score.

Conclusions

Depression in primary TKA and higher medical comorbidity in revision TKA cohorts were associated with suboptimal improvement in index knee function. It remains to be seen whether strategies focused at optimization of medical comorbidities and depression pre- and peri-operatively may help to improve TKA outcomes. Study limitations include non-response bias and the use of diagnostic codes, which may be associated with under-diagnosis of conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a very successful surgery for patients with end-stage arthritis. TKA is associated with significant improvements in pain, function and quality of life [1]. Related to the obesity epidemic, increasing longevity and the expansion of TKA indications to both younger and older patients, the annual incidence of TKA is increasing at an exponential rate [2, 3]. Post-TKA functional limitations constitute a significant problem. We need a better understanding of factors associated with failure to improve index knee function after TKA.

Previous studies examining the effect of medical and psychological comorbidity on knee function after TKA have provided contradictory results. Some studies found that higher medical comorbidity was associated with poorer function [4–6], but others reported no association [7–11]. Similarly, some studies reported that depression was associated with poor functional outcomes after TKA [12–14], but others did not [15, 16]. While the reasons for these contradictory findings are unclear, there is clearly a lack of consistent evidence of association of medical and psychological comorbidity with knee function after TKA. Not surprisingly, a recent systematic review of psychological factors affecting outcomes of knee or hip arthroplasty concluded “…strong evidence was found that preoperative depression had no influence on postoperative functioning” [14]. Four key limitation of most previous studies were that: (1) they consisted of small sample sizes and were likely underpowered; (2) multivariable-adjustment for potential confounders was not done in all studies, thereby increasing the possibility of bias; (3) they provided a mean change in function score at the cohort level (averaging of excellent, good and poor results), which is difficult to extrapolate to patient level benefit, varying in their improvement in function after TKA; and (4) very few studies included patients with revision TKA. An easier way to understand arthroplasty results is to examine the proportion of patients who achieve a clinically meaningful improvement in function, reported only rarely in arthroplasty studies [17]. Such information can be very helpful to patients and policy makers. Thus, we need better-designed studies. The aim of this study was to examine whether medical and psychological comorbidity at the time of TKA associated with a clinically meaningful function improvement after TKA. We hypothesized that higher medical comorbidity, depression and anxiety at the time of TKA, will each be independently associated with poorer patient-reported subjective functional outcome after primary and revision TKA.

Methods

We describe the methods and results of this observational study as recommended in the Strengthening of Reporting in Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [18].

Data source and study population

We used prospectively collected data from the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived the need for patient consent. The Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry captures data for all patients undergoing TKA using a validated standardized questionnaire, the Mayo knee questionnaire, that has construct validity and reproducibility [19]. Mayo knee questionnaire includes questions assessing pain and function, similar to the Knee Society Scale [20], the most commonly used outcome instrument in TKA patients. The Mayo knee questionnaire was administered to patients during an in-person clinic visit, by mail or by a phone call by trained, dedicated registry staff, at 2- and 5-year time-points post-arthroplasty. Patients were included in this study if they had undergone a primary or revision TKA during 1993–2005 and completed the patient questionnaire at 2- or 5-years post-TKA [21].

Outcome of interest

Improvement in self-reported subjective knee function compared to the preoperative status was the outcome of interest. It was assessed with a single question: Compared to your condition before your knee surgery, how would you rate your knee function? There were four possible responses: much better, better, same, worse. Patient responses were categorized into ‘much better’ and ‘better’ categories versus the reference category comprising of ‘same’, or ‘worse’. This was based on the assumption that most patients aim and expect to achieve ‘much better’ knee function after TKA, although some may be satisfied with ‘better’ knee function. Thus, both constitute clinically meaningful improvements. Same or worse knee function after TKA, an elective surgical procedure, is clearly undesirable. This question has been used previously to assess patient outcomes in knee and hip arthroplasty populations [21].

Predictors of interest and covariates

The main predictors of interest assessed were medical and psychological comorbidity at the time of index TKA. Medical comorbidity was measured using Deyo-Charlson index, a validated measure of comorbidity [22]. Deyo-Charlson index consists of a weighted scale of 17 comorbidities (including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease, diabetes, diabetes with end-organ damage, hemiplegia, moderate or severe renal disease, tumor without metastasis, leukemia, lymphoma, moderate or severe liver disease, metastatic solid tumor and AIDS), expressed as a summative score. It is the most commonly used comorbidity measure in the medical literature and is associated with important outcomes such as mortality, hospitalization and outpatient utilization in populations similar to our cohort [22–24]. The presence of anxiety or depression was assessed based on the presence of the respective ICD-9-CM codes at the time of index TKA, as in previous studies [25–28].

We adjusted the analyses for important covariates and confounders, previously shown to be associated with TKA outcomes (demographics, diagnosis etc.) [10, 29–33] or hypothesized to impact outcome, such as distance from medical center due to higher complexity of referred patients versus local patients and differences in expectations which is associated with TKA outcomes [34–36]. Data on these covariates/confounders were obtained from the joint registry and institutional clinical databases. Multivariable-adjusted analyses included the following covariates and confounders:

-

(1)

Demographics: age, categorized as ≤60, >60-70, >70-80, >80, as previously [29, 37]; gender; and body mass index (BMI), categorized as normal or underweight, <25, overweight, 25–29.9, obese, 30–34.9, very obese, 35–39.9, or extremely obese, ≥40 as previously, as per WHO classification [38];

-

(2)

American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status score, categorized as class I-II vs. III-IV, as previously [26, 39], a validated measure of peri-operative mortality and immediate post-operative morbidity [40];

-

(3)

Distance from medical center (0–100 miles, >100-500 miles, >500 miles), categorized as previously [26, 30], calculated by using zip codes and country codes from the patients’ registration records at the time of surgery (if available) or at present;

-

(4)

Operative diagnosis: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid/inflammatory arthritis, or other (avascular necrosis, fracture etc.) for primary TKA; loosening/wear/osteolysis, dislocation/bone or prosthesis fracture/instability/non-union or failed prior arthroplasty with components removed/infection for revision TKA; and

-

(5)

Implant fixation: cemented or uncemented/hybrid, for primary TKA only.

Statistical analyses

We used univariate logistic regression models to assess the crude (unadjusted) association between medical comorbidity, anxiety and depression and the improvement in knee function 2- and 5-years after primary or revision TKA. Multivariable-adjusted models were used to decrease confounding bias by including all pre-specified covariates significantly associated with outcome and potential confounders. Multivariable-adjusted models included Deyo-Charlson index, anxiety, depression, age, gender, BMI, ASA class, operative diagnosis, distance from the medical center (for both primary and revision TKA) and implant fixation (primary TKA only). Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were reported. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All regression analyses used a generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach to adjust the standard errors for the correlation between observations on the same subject due to both knees having been replaced and/or multiple operations on the same knee. We used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 (Chicago, IL) to perform analyses.

IRB approval

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Results

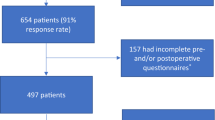

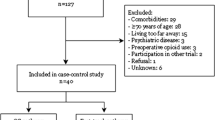

We studied 7,139 primary TKAs at 2- and 4,234 at 5-years and 1,533 revision TKAs at 2- and 881 at 5-years. For the primary TKA 2-year cohort, the mean age was 68 years, 18% were 60 years or younger, 9% had BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more and 56% were women. Eleven percent had depression, 6% had anxiety, 8% had heart disease, mean Deyo-Charlson index was 1.2, 98% implants were uncemented and osteoarthritis was the underlying diagnosis in 94% (Table 1). Other demographic and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1. Survey response rates for primary or revision TKA were 65% and 57% at 2-years and 57% and 48% at 5 years, respectively. For primary TKA, men, older age and a diagnosis of osteoarthritis had higher likelihood and patients with higher ASA class, higher Deyo-Charlson score and living >500 miles from the medical center had a lower likelihood of responding to the survey (Table 2). Similar characteristics were associated with non-response in the revision TKA group (Table 2).

Depression, anxiety and Improvement in Knee Function after Primary TKA

At 2-years after primary TKA, 87% reported much better and 10% better knee function compared to preoperatively, and at 5-years, 85% and 10%, respectively. At 2-year follow-up, depression was associated with lower odds of much better knee function (p < 0.01) in univariate analyses (Table 3) as well as lower odds of 0.5 of much better knee function (p = 0.02) after multivariable-adjustment (Table 4). Anxiety was not associated with subjective knee function improvement at 2-years (p ≥ 0.50). At 5-years, depression or anxiety were not significantly associated with knee function improvement (Table 4).

Depression, anxiety and improvement in knee function after revision TKA

At 2-years after revision TKA, 65% reported much better knee function and 20% better knee function compared to preoperatively, and at 5-years, 63% and 21%, respectively. In univariate analyses at 5-years after revision TKA, depression was associated with lower odds of much better knee function (p = 0.05) (Table 5). In multivariable-adjusted analyses, this was no longer significant (p = 0.17; Table 4). At 5-years, in multivariable-adjusted analyses, neither depression nor anxiety were associated with knee function.

Medical comorbidity and improvement in knee function after primary TKA

In univariate analyses, at 2-year follow-up, Deyo-Charlson index was associated with a statistically non-significant trend with much better knee function (p = 0.10) (Table 3). This was no longer significant after multivariable-adjustment, (p = 0.47) (Table 4). At 5-years, Deyo-Charlson index was not significantly associated with knee function improvement (p = 0.25; Table 2).

Medical comorbidity and improvement in knee function after revision TKA

In univariate analyses at 2 and 5-years after revision TKA, Deyo-Charlson had a non-statistically significant association with much better knee function (p = 0.50 and 0.13; Table 5). In multivariable-adjusted analyses, higher Deyo-Charlson index was associated with significantly lower odds of 0.5 of much better knee function (p = 0.05; Table 4) and a trend towards significantly lower odds of 0.4 of better knee function (p = 0.07; Table 4) at 5-years. No significant associations were noted at 2-years (p > 0.20).

Discussion

In this study we found that psychological and medical comorbidity were associated with less optimal improvement in knee function after TKA. Specifically, depression was associated with suboptimal knee function improvement at 2-years after primary TKA and higher medical comorbidity score with suboptimal knee function improvement at 5-years after revision TKA.

An interesting finding from our study was the association of depression with suboptimal improvement in index knee function 2-years after primary TKA. Several factors may contribute. Depressed patients are less likely to successfully complete rehabilitation therapy [41, 42] that is required post-TKA. They may not follow-up with their surgeon regularly due to concomitant depression and may have worse post-operative pain, which may impact adherence with rehabilitation therapy. Optimal physical rehabilitation after TKA is the key to best results after TKA [43, 44]. The absence of this association in primary TKA at 5-years may be either due to a smaller sample size making it underpowered analysis or due to “catching up” by patients with depression after 2-years. The differences in findings between primary and revision TKA may be due to differences in patient characteristics (depression, mean Deyo-Charlson index), the underlying diagnosis and in the rate of complications between primary and revision TKA.

Two recent studies reported that depression was associated with poor functional outcomes after primary TKA [12, 13], while other studies failed to confirm this finding [15, 16]. Two studies examined function only up to 1-year [12, 15], one study at 2-years [16] and one at 5-years [13]. Most studies had small sample size, making them underpowered and at risk of missing a significant association. By analyzing a large sample and performing multivariable-adjusted analyses, our study adds to this body of knowledge related to association of depression with improvement in knee function after TKA. Three key differences between our study and the previous studies are that we used a large sample and our outcome was joint-specific and can be interpreted as a patient-level clinically meaningful outcome. This is in contrast to the use of mean scores on lower limb-specific instrument (Western Ontario McMaster osteoarthritis Index, WOMAC) or lower-limb specific/knee-specific hybrid outcome (such as Knee society score, KSS) in previous studies. Our study extends and confirms previous findings from the positive studies of depression and poor functional outcome. Our finding of no association of anxiety with functional improvement outcomes is important and confirms a previous similar finding in a study with 5-year follow-up [13]. This may be related to smaller sample size at 5-years.

We found that higher medical comorbidity (on Deyo-Charlson index) was significantly associated with suboptimal improvement in knee function 5-years after revision TKA. Previous studies have shown that diabetes and hypertension are associated with higher post-arthroplasty complication rates [45]. Poorer functional outcome associated with higher comorbidity may be partially due to higher post-operative complication rates. A higher comorbidity may also interfere with optimal adherence to physical rehabilitation. In those with primary TKA, evidence is contradictory with some studies finding an association of higher medical comorbidity with poorer function [4–6] and others no such association [7–11]. We did not note any significant association of higher comorbidity at baseline with 2-year outcomes. It is possible that a longer follow-up allows for a more significant impact of comorbidity on TKA outcomes compared to a shorter follow-up, since chronic diseases get worse with longer disease duration, in general. In absence of any previous studies examining patient-level meaningful improvements, these findings are novel and need confirmation in future studies. Studies of improvement of knee function after TKA are important. A $12 million research grant 2010 by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to study factors associated with functional outcomes and complications after joint replacement is strongly supportive [46]. Our study adds to this growing area of research by studying comorbidity factors as risk factors for poor patient-reported knee function improvement.

Our study has several limitations. Non-response may have biased our findings. Survey responders had characteristics previously shown to be associated with better outcomes (male gender, older age, a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, lower ASA class, lower Deyo-Charlson score, shorter distance to medical center), but it is unclear how the non-response bias might influence the association of depression and medical comorbidity with function outcomes. A lower response rate at 5-years compared to 2-years makes these findings more prone to bias. Since both anxiety and depression were captured based on presence of a diagnostic code, and psychological comorbidities may be under-recognized and under-diagnosed, it is likely that we missed some cases. This might have biased our estimates towards null, and we may have missed some important associations of anxiety and depression with outcomes. A retrospective study design did not allow us to have confirmation of depression/anxiety diagnosis by examination by a psychologist of psychiatrist. However, the prevalence of depression is similar to the 9-15% reported in studies using validated instruments for depression [47–49]. Whether the “much better” is truly different from “better” response on this ordinal scale can not be determined in this study; however, this ordinal response is similar to other validated ordinal scales, commonly used in health outcome assessments [50, 51]. Recall bias should be considered while interpreting these results; patients may have over- or under-estimated the functional improvements, and therefore the direction of impact of this bias on our study findings is unclear. Several study strengths must also be noted. We included a large sample size with adequate number of events to study the question of interest, used validated measures (questionnaire, Deyo-Charlson index), performed multivariable-adjusted analyses, examined both 2- and 5-year outcomes in primary and revision TKA and provided results for a clinically meaningful joint-specific functional improvement outcome.

Conclusion

In summary, in this study using a U.S. institutional joint registry, we found that preoperative depression was associated with less improvement in index knee function 2-years after primary TKA and higher preoperative Deyo-Charlson index was associated with suboptimal improvement in knee function 5-years after revision TKA. These findings clarify the role of medical and psychological comorbidity in functional improvement in the index knee after TKA. Patients with depression may benefit by optimization of behavioral and medical therapy for depression prior to and after primary TKA. Similarly, closer management of medical comorbidities may have an impact on functional outcomes after revision TKA. Patients with higher medical comorbidity load and/or depression should be warned about suboptimal knee function outcome. Future results from the ongoing AHRQ-funded U.S. registry study should help to identify additional factors associated with functional outcomes after TKA [46].

Abbreviations

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status score

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval.

References

Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY: Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004, 86-A (5): 963-974.

Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Melton LJ, Kurland RL, Berry DJ: A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969–2008. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010, 85 (10): 898-904. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0115.

Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M: Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007, 89 (4): 780-785. 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222.

Jones CA, Voaklander DC, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME: The effect of age on pain, function, and quality of life after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med. 2001, 161 (3): 454-460. 10.1001/archinte.161.3.454.

Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB: Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004, 86-A (10): 2179-2186.

Wasielewski RC, Weed H, Prezioso C, Nicholson C, Puri RD: Patient comorbidity: relationship to outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998, 356: 85-92.

Fitzgerald JD, Orav EJ, Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Poss R, Goldman L, Mangione CM: Patient quality of life during the 12 months following joint replacement surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 51 (1): 100-109. 10.1002/art.20090.

Fortin PR, Clarke AE, Joseph L, Liang MH, Tanzer M, Ferland D, Phillips C, Partridge AJ, Belisle P, Fossel AH, Mahomed N, Sledge CB, Katz JN: Outcomes of total hip and knee replacement: preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at six months after surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42 (8): 1722-1728. 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1722::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-R.

Meding JB, Reddleman K, Keating ME, Klay A, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Berend ME: Total knee replacement in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003, 416: 208-216.

Jones CA, Voaklander DC, Suarez-Alma ME: Determinants of function after total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2003, 83 (8): 696-706.

Kennedy DM, Hanna SE, Stratford PW, Wessel J, Gollish JD: Preoperative function and gender predict pattern of functional recovery after hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006, 21 (4): 559-566. 10.1016/j.arth.2005.07.010.

Lopez-Olivo MA, Landon GC, Siff SJ, Edelstein D, Pak C, Kallen MA, Stanley M, Zhang H, Robinson KC, Suarez-Almazor ME: Psychosocial determinants of outcomes in knee replacement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70 (10): 1775-1781.

Brander V, Gondek S, Martin E, Stulberg SD: Pain and depression influence outcome 5 years after knee replacement surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007, 464: 21-26.

Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M: Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 41 (4): 576-588. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.003.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Reardon G, Amirault D, Dunbar M, Stanish W: The role of presurgical expectancies in predicting pain and function one year following total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2011, 152 (10): 2287-2293. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.014.

Lingard EA, Riddle DL: Impact of psychological distress on pain and function following knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007, 89 (6): 1161-1169.

Singh J, Sloan JA, Johanson NA: Challenges with health-related quality of life assessment in arthroplasty patients: problems and solutions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010, 18 (2): 72-82.

STROBE Statement. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. Link: http://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_combined.pdf

McGrory BJ, Morrey BF, Rand JA, Ilstrup DM: Correlation of patient questionnaire responses and physician history in grading clinical outcome following hip and knee arthroplasty. A prospective study of 201 joint arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 1996, 11 (1): 47-57. 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80160-4.

Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN: Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989, 248: 13-14.

Singh JA, O'Byrne MM, Colligan RC, Lewallen DG: Pessimistic explanatory style: a psychological risk factor for poor pain and functional outcomes two years after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2010, 92 (6): 799-806.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992, 45 (6): 613-619. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987, 40 (5): 373-383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8.

Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Braham RL, Fields SD, Douglas RG: Morbidity during hospitalization: can we predict it?. J Chronic Dis. 1987, 40 (7): 705-712. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90107-X.

Singh JA, Lewallen DG: Medical and psychological comorbidity predicts poor pain outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013, 52 (5): 916-923. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes402.

Singh JA, Lewallen DG: Predictors of use of pain medications for persistent knee pain after primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: a cohort study using an institutional joint registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012, 14 (6): R248-10.1186/ar4091.

Singh JA, Lewallen D: Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010, 11: 90-10.1186/1471-2474-11-90.

Singh JA, Lewallen D: Age, gender, obesity, and depression are associated with patient-related pain and function outcome after revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol. 2009, 28 (12): 1419-1430. 10.1007/s10067-009-1267-z.

Singh JA, Gabriel S, Lewallen D: The impact of gender, age, and preoperative pain severity on pain after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008, 466 (11): 2717-2723. 10.1007/s11999-008-0399-9.

Singh JA, Gabriel SE, Lewallen DG: Higher body mass index is not associated with worse pain outcomes after primary or revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011, 26 (3): 366-374. 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.006. e361

Rand JA, Trousdale RT, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS: Factors affecting the durability of primary total knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003, 85-A (2): 259-265.

Schneider M, Kawahara I, Ballantyne G, McAuley C, Macgregor K, Garvie R, McKenzie A, Macdonald D, Breusch SJ: Predictive factors influencing fast track rehabilitation following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009, 129 (12): 1585-1591. 10.1007/s00402-009-0825-9. Epub 2009/02/10

Gordon SM, Culver DH, Simmons BP, Jarvis WR: Risk factors for wound infections after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Epidemiol. 1990, 131 (5): 905-916.

GonzalezSaenzde Tejada M, Escobar A, Herrera C, Garcia L, Aizpuru F, Sarasqueta C: Patient expectations and health-related quality of life outcomes following total joint replacement. Value Health. 2010, 13 (4): 447-454. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00685.x.

Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH, Katz JN: The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29 (6): 1273-1279.

Wolfe F, Zwillich SH: The long-term outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis: a 23-year prospective, longitudinal study of total joint replacement and its predictors in 1,600 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41 (6): 1072-1082. 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1072::AID-ART14>3.0.CO;2-G.

Bourne R, Mukhi S, Zhu N, Keresteci M, Marin M: Role of obesity on the risk for total hip or knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007, 465: 185-188.

WHO: Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. 2000, Geneva: World Health Organization

Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH: Cardiopulmonary complications after primary shoulder arthroplasty: A Cohort Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 41 (5): 689-697. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.09.003. Epub 2011/11/08

Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE: The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961, 178: 261-266. 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001.

McGrady A, McGinnis R, Badenhop D, Bentle M, Rajput M: Effects of depression and anxiety on adherence to cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardpulm Rehabil Prev. 2009, 29 (6): 358-364. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181be7a8f.

Glazer KM, Emery CF, Frid DJ, Banyasz RE: Psychological predictors of adherence and outcomes among patients in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 2002, 22 (1): 40-46. 10.1097/00008483-200201000-00006.

Brueilly KE, Pabian P, Straut L, Freve L, Kolber M: Factors contributing to rehabilitation outcomes following hip arthroplasty. Phys Ther Rev. 2012, 17 (5): 301-310. 10.1179/1743288X12Y.0000000027.

Bade MJ, Stevens-Lapsley JE: Early high-intensity rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty improves outcomes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011, 41 (12): 932-941. 10.2519/jospt.2011.3734.

Jain NB, Guller U, Pietrobon R, Bond TK, Higgins LD: Comorbidities increase complication rates in patients having arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005, 435: 232-238.

FORCE-TJR: Function and Outcomes Research for Comparative Effecetiveness in Total Joint Replacement.http://www.force-tjr.org,

Ma Y, Balasubramanian R, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Hebert JR, Phillips LS, Goveas JS, Culver AL, Olendzki BC, Beck J, Smoller JW, Sepavich DM, Ockene JK, Uebelacker L, Zorn M, Liu S: Relations of depressive symptoms and antidepressant use to body mass index and selected biomarkers for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 2013, 103 (8): e34-e43. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301394.

Zhang X, Bullard KM, Cotch MF, Wilson MR, Rovner BW, McGwin G, Owsley C, Barker L, Crews JE, Saaddine JB: Association between depression and functional vision loss in persons 20 years of age or older in the United States, NHANES 2005–2008. JAMA Ophthal. 2013, 131 (5): 573-581. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2597.

Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Tsai J, Balluz LS: A comparison of depression prevalence estimates measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire with two administration modes: computer-assisted telephone interviewing versus computer-assisted personal interviewing. Int J Pub Health. 2012, 57 (1): 225-233. 10.1007/s00038-011-0253-9.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992, 30 (6): 473-483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002.

Shaw M, Dent J, Beebe T, Junghard O, Wiklund I, Lind T, Johnsson F: The Reflux Disease Questionnaire: a measure for assessment of treatment response in clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008, 6: 31-10.1186/1477-7525-6-31.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/127/prepub

Disclaimer

“The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government”.

Grant support

This material is the result of work supported with research grants from the Mayo Clinic Orthopedic Surgery research funds and the resources and use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Alabama, USA. J.A.S. is also supported by grants from the Agency for Health Quality and Research Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics (CERTs), National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), National Institute of Aging (NIA) and National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There are no financial conflicts related directly to this study. JAS has received research and travel grants from Takeda and Savient; and consultant fees from Savient, Takeda, Regeneron and Allergan. DGL has received royalties/speaker fees from Zimmer, Orthosonic and Osteotech, has been a paid consultant and owns stock in Pipeline Biomedical and his institution has received research funds from DePuy, Stryker, Biomet and Zimmer.

Authors’ contributions

JAS: Study conception and design, development of study protocol methods and analyses, review of statistical analyses, drafting, critical revisions and submission of the manuscript, approval of the final manuscript version. DGL: Review and revision of study design and study protocol, statistical analyses, critical revisions and approval of the final manuscript version. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, J.A., Lewallen, D.G. Depression in primary TKA and higher medical comorbidities in revision TKA are associated with suboptimal subjective improvement in knee function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15, 127 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-127

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-127