Abstract

Background

The prevalence of hypertension is rising worldwide with an estimated one billion people now affected globally and is of near epidemic proportions in many parts of South Asia. Recent turmoil has until recently precluded estimates in Afghanistan so we sought, therefore, to establish both prevalence predictors in our population.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of adults ≥40 years of age in Kabul from December 2011-March 2012 using a multistage sampling method. Additional data on socioeconomic and lifestyle factors were collected as well as an estimate of glycaemic control. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were undertaken to explore the association between hypertension and potential predictors.

Results

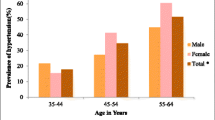

A total of 1183 adults (men 396, women 787) of ≥ 40years of age were assessed. The prevalence of hypertension was 46.2% (95% CI 43.5 – 49.3). Independent predictors of hypertension were found to be: age ≥50 (OR = 3.86, 95% CI: 2.86 – 5.21); illiteracy (OR = 1.90, 1.05 – 1.90); the consumption of rice >3 times per week (OR = 1.43, 1.07 – 1.91); family history of diabetes (OR = 2.20, 1.30 – 3.75); central obesity (OR = 1.67, 1.23 – 2.27); BMI ≥ 30 Kg/meter squared (OR = 2.08, 1.50 – 2.89). The consumption of chicken and fruit more than three times per week were protective with ORs respectively of 0.73 (0.55-0.97) and 0.64 (0.47 – 0.86).

Conclusions

Hypertension is a major public health problem in Afghan adults. We have identified a number of predictors which have potential for guiding interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High blood pressure is at epidemic levels globally. An estimated 1 billion people are affected [1–3] with particularly high prevalence in parts of South Asia thought to be a result of a combination of genetic susceptibility and lifestyle transition [4, 5]. Predictors of hypertension in High Income Countries (HIC) include family history, age, race, obesity, physical inactivity, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, excessive salt intake and excessive alcohol intake [2, 3].

In Afghanistan, due to years of conflict, it has been impossible to make any robust estimates of non-communicable disease prevalence. There is, however, no reason to believe that Afghans are less susceptible to non-communicable disease and estimates are therefore urgently required. The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of hypertension and assess the predictors in urban Afghan adults.

Methods

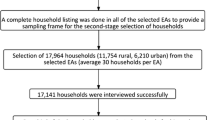

We conducted a cross-sectional study between December 2011 and March 2012 to estimate the prevalence of hypertension and its associated factors in Kabul. All adults aged 40 years and over who had been residing for at least one year or more in the 17 districts of Kabul city were eligible. The city has approximately 3,289,000 inhabitants living in 17 residential districts made up of neighborhoods (Gozar) comprised of 534,900 households [6]. We requested the Kabul municipality to provide a list of all neighborhoods and their representatives and were able to study 13 districts. To balance considerations of cost, resources, and time without compromising the representativeness of the sample, a two-phase cluster sampling technique was used as follows. Eligible subjects were selected by multistage sampling: in the first stage, a sample of neighborhoods was selected randomly from each district. In the second stage, a main masjid (mosque) was selected as a hallmark and heads of households around the masjid were asked to approach the team settled there. Finally, one adult from each household was randomly selected and interviewed after written consent was obtained.

Sample size estimation was based on a prior specified precision level of 5% and the assumption that the proportion of potential risk was similar to other studies conducted in other similar settings. We adjusted for intracluster correlation and concluded that 1,200 participants would be required.

One member from each household aged 40 years and over was interviewed using a proforma designed for the study. Height and weight were measured by measurement tape and electronic weighing scale. Using standard international criteria, we defined a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 as obese and a BMI of 25–30 kg/m2 as overweight. A BMI of 18.5 to 25 kg/m2 was considered normal. A waist circumference of ≥ 94 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women were considered centrally obese [7, 8].

Blood pressure was measured by twice by android sphygmomanometer in the sitting position on the left arm. Before analysis, blood pressure was dichotomized to hyper- or normotension by either systolic of ≥ 140 mmHg, or diastolic of ≥ 90 mmHg, or both. Those already on treatment were considered hypertensive irrespective of our own readings. Fasting blood sugar was tested using portable glucometer once in the morning before breakfast and analysed by the glucose oxidase method (check-ref). Data was single entered and, after cleaning, analysis was undertaken on 1,183 individuals [9]. Data on potential covariates such as: age, sex, ethnicity, family history of the disease, educational status, income, residential area, obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, snuff using, physical activity and dietary behavior were collected through the structured pretested and modified questionnaire. No questions were made about alcohol as Afghanistan is an Islamic state and alcohol is considered a narcotic and is illegal. For normally distributed variables, we calculated mean and Standard Deviation (SD). For categorical variables we used chi-Squared and logistic regression and derived both uni- and multivariate estimates of Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI). Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 [10].

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Ministry of Public Health, Afghanistan.

Results

Descriptive data (Table 1)

The mean age of the study subjects was 49.5 years and most (59.3%) were aged between 40 and 50 years. Sixty eight percent of the participants were ethnic Tajik and 20.7% were ethnic Pashtuns. Two thirds were female. Most study participants were illiterate with a monthly income of 2,000 to 6,000 Afghanis (AFN) (One USD = 50AFN). Forty percent of participants were unemployed or were casual laborers, while 25% of respondents were women engaged in home employ. Twenty two percent were government employees and the rest were engaged in the agricultural industry as farmers. Approximately 3.3% of respondents were retired and too old to engage in physical labor. 83% of participants had no knowledge of hypertension but only 14% were smokers. The prevalence of either systolic or diastolic hypertension was 46.2% (95% CI 43.5 – 49.3). The distribution of both systolic and diastolic blood pressure can be reviewed in Figures 1 and 2.

Multivariate analysis

Hypertension was associated with age but not gender. Literacy was protective (OR for illiteracy = 1.90 95% CI: 1.05 – 1.90 and P value <0.05) but level of income, smoking status and knowledge of diseases were not predictive. Unemployment and inability to work predicted hypertension ORs = 2.04 (95% CI: 1.49 – 2.78) and 1.69 (95% CI: 1.20 – 2.38) respectively. The results for bivariate analysis can be reviewed in Table 2 and for multivariate analysis in Table 3.

Discussion

Our study shows a prevalence of hypertension in Kabuli adults of close to 50%, which is comparable to that in many HIC settings. Predictors included illiteracy, obesity, low levels of physical activity and a family history of diabetes. A higher dietary quality (measured by higher chicken and fruit intake) had a modest protective effect but given the attenuation in the multivariate model it is possible that this association is simply a marker for other social factors. In keeping with the natural history of hypertension, prevalence increased with age.

Strengths of the study include the breadth of sampling across the city and two stage methods.

Our study is unique in Afghanistan in which any research over the last 15 years has been near impossible as a result of chronic warfare and instability.

Limitations of the study include the sampling. For logistical reasons our study was household rather than community based and, therefore, less likely to be involved in regular work. It is possible that the participants were less active or different in other ways to their employed counterparts and may, therefore, not have been representative of all Kabuli adults. We would have liked to undertake more comprehensive assessment of glucose tolerance but were precluded by budgetary constraints.

Our findings were consistent with work in similar settings. In rural Nepal, Khan showed that a high BMI and low socio-economic status were associated with increase odds of hypertension [11]. Other studies in Iran, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Angola and China found similar findings that older age, high blood glucose level, lower level of education, retirement/unemployment and higher body mass index were significantly associated with hypertension [12–17].

Literacy was an independent predictor of hypertension but the association between education and health is a complex one. Though in some settings it may be a marker of (and confounded by) socio economic status, there is no doubt that literacy enhances health awareness an association that has been demonstrated in numerous studies. To this effect, literacy was selected as a target for the Millennium Development Goals by the WHO and UN [11, 18, 19]. In Afghanistan, as a result of political forces the provision of universal literacy has been complex and challenging. This has been most marked for girls but, at the time of writing, the country is for the first time holding independent elections and we can only hope that education is marked as a priority for the new government.

The other predictors, sedentary lifestyle, obesity and impaired glucose tolerance are all potentially amenable to intervention at a public health level. Sedentary lifestyles may stem from a lack of activity in school. If education were to be available universally and physical activity a mandatory part of the school day, there is every reason to believe that this can be inculcated from an early age for life. Though there may be cultural sensitivities, they can be overcome as Almas and colleagues demonstrated in an innovative study in urban Pakistan [20]. Other than education, better use of the media to inform the population has a role particularly as most households now have at least a television. Subsidising blood pressure checks in primary medical care would additionally encourage update of screening. We feel that, given our findings, both mass and targeted intervention would be feasible. We have shown that Afghanistan is equally at risk of hypertension and has the same risk factors as other populations. As the conflict subsides, our attention must turn to another threat, that of the non-communicable diseases epidemic.

Conclusion

Though instability has hitherto precluded detailed study, this unique study has shown that hypertension and obesity is at epidemic proportions in household adults in Kabul. As Afghanistan enters a new era, intervention is now a Public Health priority.

References

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J: Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9455): 217-223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1.

Fauci S, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J: Harrison’s principles of Internal Medicine. Factors that contribute to High Blood Pressure: The American Heart Association. 2008, New York, USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, 17

World Health Organization: 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. 2008, Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization Press

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K: Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004, 22: 11-19. 10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003.

Central Statistics Organization, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Population Statistics: Population Estimation 2012–2013. 2012, Kabul-Afghanistan: CSO Press, Available online at: http://cso.gov.af/fa/page/demography-and-socile-statistics/demograph-statistics/3897

Jose Aponte J, Brown D, Collins H, Copeland J, Haines J, Islam A, Jones G, Knudsen E, Mir R, Nitschke D, Worsham C: Epi Info [computer program]. Version 3.5.1. 2008, NY, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

World Health Organization: Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. 2000, Geneva: World Health Organization, WHO Technical Report Series No.894

Alberti SG, Zimmet P: The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definitions of the Metabolic Syndrome. 2006, Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, Available online: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetS_update2006.pdf

IBM Corp.: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 20.0. 2011, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Veghari G, Sedaghat M, Maghsodlo S, Banihashem S, Moharloei P, Angizeh A, Tazik E, Moghaddami A: Impact of literacy on the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in adults in Golestan Province (northern Iran). Caspian J Int Med. 2013, 4 (1): 580-584.

Pires JE, Sebastiao YV, Langa AJ, Nery SV: Hypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and control. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13 (1): 90-10.1186/1471-2458-13-90.

Sit JW, Sijian L, Wong EM, Yanling Z, Ziping W, Jianqiang J, Yanling C, Wong TK: Prevalence and risk factors associated with prehypertension: identification of foci for primary prevention of hypertension. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010, 21 (6): 461-469.

Meshram II, Arlappa N, Balkrishna N, Rao KM, Laxmaiah A, Brahmam GN: Prevalence of hypertension, its correlates and awareness among adult tribal population of Kerala state, India. J Postgrad Med. 2012, 58 (4): 255-261. 10.4103/0022-3859.105444.

Ordinioha B: The prevalence of hypertension and its modifiable risk factors among lecturers of a medical school in Port Harcourt, south-south Nigeria: implications for control effort. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013, 16 (1): 1-4. 10.4103/1119-3077.106704. doi:10.4103/1119-3077.106704

Baltaci D, Erbilen E, Turker Y, Alemdar R, Aydin M, Kaya A, Celer A, Cil H, Aslantas Y, Ozhan H: Predictors of hypertension control in Turkey: the MELEN study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013, 17 (14): 1884-1888.

Ibrahim KR, Nariman A, Hijazi NA, Al- Bar AA: Prevalence and Determinants of Prehypertension and Hypertension among Preparatory and Secondary School Teachers in Jeddah. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2008, 83 (14): 183-203.

Katulanda P, Ranasinghe P, Jayawardena R, Constantine GR, Rezvi Sheriff MH, Matthews DR: The prevalence, predictors and associations of hypertension in Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional population based national survey. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014, Epub ahead of print

Veghari G, Sedaghatb M, Maghsodlob S, Banihashemb S, Moharloeib P, Angizehb A, Tazikb E, Moghaddamib A: Influence of education in the prevalence of obesity in Iranian northern adults. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013, 4 (1): 30-33. 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.002

Khan RJ, Stewart CP, Christian P, Schulze KJ, Wu L, LeClerq SC, Khatry SK, West KP: A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and risk factors for hypertension in rural Nepali women. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13: 55-10.1186/1471-2458-13-55.

Almas A, Islam M, Jafar T: School-based physical activity programme in preadolescent girls (9–11 years): a feasibility trial in Karachi, Pakistan. Arch Dis Child. 2013, 98 (7): 515-519. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303242.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/386/prepub

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Jawad Asgar, FELTP Advisor and Dr Jamil Ansari Senior Instructor of FELTP in Pakistan for their contribution in design of the study. In addition the Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Training Network (EMPHNET) is thanked for their assistance in contribution of data via data analysis course in Amman in 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There is no financial or non-financial competing interest of authors in this paper.

Authors’ contributions

KMIS has been involved in conception, design, and implementation and reporting of the study. MHR has been involved in analysis and report writing while NB has reviewed the whole paper including analysis and interpretations. He has copy edited the manuscript to get ready for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Saeed, K.M.I., Rasooly, M.H. & Brown, N.J. Prevalence and predictors of adult hypertension in Kabul, Afghanistan. BMC Public Health 14, 386 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-386

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-386