Abstract

Background

Anaemia is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease and treating anaemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD) may improve outcomes. However, little is known about the scope to improve primary care management of anaemia in CKD.

Methods

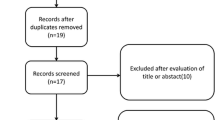

An observational study (N = 1,099,292) with a nationally representative sample using anonymised routine primary care data from 127 Quality Improvement in CKD trial practices (ISRCTN5631023731). We explored variables associated with anaemia in CKD: eGFR, haemoglobin (Hb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), iron status, cardiovascular comorbidities, and use of therapy which associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, oral iron and deprivation score. We developed a linear regression model to identify variables amenable to improved primary care management.

Results

The prevalence of Stage 3–5 CKD was 6.76%. Hb was lower in CKD (13.2 g/dl) than without (13.7 g/dl). 22.2% of people with CKD had World Health Organization defined anaemia; 8.6% had Hb ≤ 11 g/dl; 3% Hb ≤ 10 g/dl; and 1% Hb ≤ 9 g/dl. Normocytic anaemia was present in 80.5% with Hb ≤ 11; 72.7% with Hb ≤ 10 g/dl; and 67.6% with Hb ≤ 9 g/dl; microcytic anaemia in 13.4% with Hb ≤ 11 g/dl; 20.8% with Hb ≤ 10 g/dl; and 24.9% where Hb ≤ 9 g/dl. 82.7% of people with microcytic and 58.8% with normocytic anaemia (Hb ≤ 11 g/dl) had a low ferritin (<100ug/mL). Hypertension (67.2% vs. 54%) and diabetes (30.7% vs. 15.4%) were more prevalent in CKD and anaemia; 61% had been prescribed aspirin; 73% non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); 14.1% warfarin 12.4% clopidogrel; and 53.1% aspirin and NSAID. 56.3% of people with CKD and anaemia had been prescribed oral iron. The main limitations of the study are that routine data are inevitably incomplete and definitions of anaemia have not been standardised.

Conclusions

Medication review is needed in people with CKD and anaemia prior to considering erythropoietin or parenteral iron. Iron stores may be depleted in over >60% of people with normocytic anaemia. Prescribing oral iron has not corrected anaemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anaemia is an independent risk marker for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and it is a common complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1–3]. CKD is divided into stages 1 to 5, with stage 3 sub-divided into two sub-stages, 3A and 3B. Haemoglobin (Hb) levels decline as renal function deteriorates [4]. The prevalence of anaemia (Hb less than 12 g/dl in men and 11 g/dl in women) is 1% in people with stage 3 CKD; 9% in stage 4; and 33% in stage 5 CKD [5]. Anaemia affects over two-thirds (68%) of people starting dialysis [6]; and 49.6% of men and 51.2% of women in stage 4 and 5 CKD not referred to renal specialists are anaemic [7]. Anaemia in patients with CKD and end stage renal disease (ESRD) has been associated with fatigue and reduced exercise capacity; poorer quality of life, higher incidences of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) [8–12]. Diabetes mellitus is also associated with a doubling of the prevalence of anaemia in CKD [13]; there are also concerns that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) are associated with anaemia [14].

Patients with CKD have a high cardiovascular risk and effective anaemia management may improve outcomes [15–17]. Partial correction of anaemia in CKD patients has been associated with reduced LVMI and left ventricular hypertrophy [18, 19], improved cardiovascular outcomes [20], lower rate of transfusions [21], improved quality of life [9], and, delayed renal failure progression in predialysis nondiabetic patients [22] and improved renal function in patients with severe heart failure [23]. In the UK the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends evaluation of possible causes of anaemia where Hb ≤ 11 g/dl and treatment with intravenous iron and erthyropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) to maintain Hb in the range 10-12 g/dl [24, 25]. Anaemia treatment with ESA has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in non-CKD patients with CVD [23, 26, 27]. However, in CKD ESA use has failed to show a positive effects on CVD mortality and is instead associated with some negative clinical outcomes especially where Hb is corrected to over 12 g/dl [3, 28–30]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends to consider starting ESA treatment only when the Hb level is less than 10 g/dl for non-dialysis people with the CKD and anaemia [31].

Despite advances in the use of ESA for CKD patients, there is low uptake of this therapy [16]. Although it is suggested up to 10% of patients in Primary Care in UK have CKD [15] and up to 6% of CKD patients have anaemia [17] little is known about the aetiology, iron store status, and the extent to which family physicians may have tried to treat anaemia in practice.

We carried out this cross-sectional study to report the prevalence of anaemia in CKD, examine its association with cardiovascular diseases, and assess whether practitioners had attempted to treat the patients with oral iron.

Methods

We used data from the Quality Improvement in Chronic Kidney Disease (QICKD - ISRCTN5631023731) trial [32, 33]. The QICKD trial was conducted in 127 practices drawn from localities across England and contains extracts from the records of all registered patients within these practices, a total of 1,099,296 people. The population profile approximates to the national average in the 2001 Census with a small excess of working age people and slightly fewer older people aged 60 to 75 years (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The QICKD trial practices are usual general practices with routine data expected to be similar to those found in other practices. These data were collected at the trial mid-point between December 2009 and July 2010 using well established methods [34, 35]. Our dataset included demographic details: age, gender, ethnicity and deprivation score. The latter used the index of multiple deprivation (IMD) [36]. Deprivation is a concept that overlaps with, but is not synonymous with poverty. IMD is calculated across the UK based on seven constituent parts to allow comparisons between areas. The seven domains of deprivation are: (1) income, (2) employment, (3) health deprivation and disability, (4) education skills and training, (5) barriers to housing and services, (6) crime and (7) the living environment. IMD is divided into deciles of equal sizes, where the first decile (IMD ≤5.63) is the least deprived and decile ten (IMD ≥ 45.33) the most deprived.

We defined cases of stages 3 to 5 CKD by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), taking into account the requirement of three month period of chronicity for formal diagnosis. Wherever available we used laboratory calculated eGFR because it is subject to a national calibration scheme [37]. We describe people with eGFR ≥90 ml/min/1.73 m2 as having a normal eGFR, those with eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and <90 ml/min/1.73 m2 as having “mildly impaired renal function.” We subdivide those with an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 into stages 3A, 3B, 4 and 5 using conventional eGFR ranges [38]. Where we use the term “CKD” alone we mean stage 3 to 5 CKD. We did not include diagnostic codes for CKD as these under-report the prevalence of CKD [39].

We extracted a dataset that included Hb, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and common potential causes of anaemia so that we could differentiate between renal and other causes of anaemia. We defined anaemia as Hb ≤ 11 g/dl in line with NICE guidance [24].

We report the prevalence of Hb measurement among people with CKD and compare their Hb with those in people without CKD. We also explored what proportion of people had a recent measure of Hb, which we define as a recording within the last two years. We classify anaemia into micro-, normo- and macrocytic based on the MCV. Microcytic anaemia is defined as an MCV of <80 fl, normocytic as 100-80 fl, and macrocytic as >100 fl [40]. We also extracted ferritin values, as marker of iron stores. In CKD stage 3–4, iron deficiency was defined as ferritin <100ug/ml [41, 42] as patients with depleted iron stores benefit from intravenous iron even where their MCV is normal; [43] though we also report ferritin < 15 ug/ml as this has been proposed as a lower limit of normal [44, 45].

To explore the association between age and anaemia the prevalence of anaemia by eGFR category and age band we report the change using previously described groupings [46].

We explored any association between CVD, CKD and anaemia. We included in our definition of cardiovascular disease (CVD) diagnoses of heart failure (HF), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, transient ischaemic attack and cerebrovascular disease (CEVD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and hypertension (HT); and diabetes mellitus.

We investigated whether anaemic patients had been prescribed aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clopidogrel or warfarin. These are medications which are all associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Finally we looked at oral iron prescriptions in order to see if iron was being prescribed to correct anaemia and to assess whether its use was associated with correction of anaemia. As intravenous iron and ESA therapy is largely provided via specialist renal units, information about parenteral iron is not contained within the family practice computerised medical record.

The data used in the study were extracted from primary care computer systems and processed using our established method [34, 47]. We analysed these data using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 18). We used simple descriptive statistics to report our findings; we used Pearson chi square to test whether proportions were significantly different reporting the probability and commenting if not significant (n.s.). We report differences in Hb between different subgroups using independent samples T-tests, reporting the mean difference and probability (p). We constructed a linear regression model to test the extent to which the variables reported in our model are predictors of any change in Hb.

We carried out a regression analysis initially testing each variable separately to explore any predictive effect on our outcome variable (Hb). We then grouped our best predictor variables into a single model reporting the unstandardised coefficient (B); it standard error (E); and significance (p). B represents the unit change in the outcome variable for either one unit of change, or the presence or absence of the predictor variable. E.g. eGFR has a B of 0.003, this means that for every 10 ml/min rise in eGFR Hb rises by 0.03 g/dl; B Stage 3 to 5 CKD is −0.482, implying that people with stage 3 to 5 CKD have an Hb 0.5 g/dl lower than those who do not. We did not include age, gender or ethnicity in our model as they are already included in the equation used to estimate renal function [48]. We did however include the use of ACE-I, ACE-I and hypertension, and hypertension alone in our model to explore any influence from a patient’s therapy. We then grouped our best predictive variables into a single model for which we additionally quote R2, the correlation coefficient which gives an effect size (i.e. to what extent the change seen can be ascribed to the variables in the model; an R2 of 0.11 implies that it contributes 11% of the change).

Ethical approval for the trial was given by the Oxford Research Ethics committee and is included in our clinical trial registration details (ISRCTN56023731) [49].

Results

Prevalence of CKD in the study population

The prevalence of CKD in the general population is 5.3% (n = 58,592); 6.76% (50,319) in people aged over 18 years. As renal function declines from normal to stage 3B CKD the mean age of the people gets older with each declining stage of CKD; those with stage 4 and 5 CKD are slightly younger (See Additional file 2: Figure S2), possibly due to survival bias.

Prevalence of micro- , normo-, and macrocytic anaemia in CKD patients

We found that 94% of people with CKD have had an Hb measurement at some time, with 70% measured within the last 2 years. The mean Hb value for patients without CKD was 13.71 g/dl (median 13.7 g/dl, SD 1.6), compared to 13.22 g/dl (median 13.3 g/dl, SD 1.6) in patients with CKD. Furthermore, prevalence of anaemia was increased in the higher CKD stages (Table 1). The overall prevalence of anaemia (Hb ≤ 11 g/dl) in people with CKD Stage 3–5 is 8.6% (n = 4,690). 3.0% (n = 1,648) have Hb ≤ 10 g/dl and 1% (n = 563) Hb ≤ 9 g/dl. 22.2% of people with CKD had anaemia as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Hb <12 g/dl in women and <13 g/dl in men).

We observed in our data that anaemia in CKD is age-independent when eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 as also found in a recent large US national cross-sectional study [46]. Anaemia prevalence increases as eGFR prevalence rises in all age groups (Figure 1). Anaemia was more common in older patients then in young patients with moderately decreased eGFR (Figure 1).

Normocytic anaemia is the most common form of anaemia in patients with CKD (Figure 2). 80.5% (n = 3,744) of patients with CKD and Hb ≤ 11 g/dl have normocytic anaemia. The proportion falls to three quarters (72.7%, n = 1,057) for Hb ≤ 10 g/dl and to two thirds (67.6%, n = 375) where Hb ≤ 9 g/dl. As Hb falls so the proportion of people with microcytic anaemia increases: from 13.4% (n = 625) where Hb ≤ 11 g/dl, to 20.8% (n = 302) where Hb ≤ 10 g/dl, to a quarter of those with Hb ≤ 9 g/dl (n = 138). The proportion of macrocytic anaemia only slightly rises as Hb falls in CKD: 6.0% (n = 280) of people with Hb ≤ 11 g/dl rising to 7.6% (n = 42) of people with Hb ≤ 9 g/dl (Table 2).

Prevalence of Iron deficiency anaemia in CKD patients

Approximately one third (31%, n = 18,157) of people with CKD have had their ferritin measured. In two-thirds (63.7%, n = 11,570) of these patients the ferritin is <100ug/mL and 2.7% (n = 1,569) had a ferritin level <15ug/mL; suggesting that they had reduced iron stores. Over three-quarters (82.7%) of people with CKD and microcytic anaemia (Hb ≤ 11 g/dl) have a ferritin less than 100 ug/mL (Chi-square, p = 0.017), compared with 58.8% of those with normocytic (Chi-square p < 0.001) and 45.5% of those with macrocytic anaemia (Chi-square p = 0.8, n.s.). Furthermore, 39% patients with CKD and microcytic anaemia have ferritin level below 15 ug/mL (Table 3).

Anaemia as a risk factor for CVD in patients with CKD

Analysis of cardiovascular co-morbidities and diabetes showed that these conditions are more prevalent among people with anaemia and CKD than those with CKD and a normal Hb. The prevalence of ischaemic heart disease (IHD), heart failure (HF), stroke and transient ischaemic attack grouped as cerebrovascular disease (CEVD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and diabetes is approximately twice that of CKD patients without anaemia (Table 4). In addition, 67.2% of patients with CKD and anaemia have hypertension as compared with 54% patients with CKD only (Chi-square p < 0.001).

Drug prescription in patients with CKD and anaemia

Two-thirds of patients (62%) in our study receive one or more drugs causing anaemia in the last two years, 84.7% ever. Nearly half of people with CKD and anaemia have been prescribed aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (49.1%, n = 2,301 and 46.2%, n = 2166 respectively), 8.1% (n = 378) received clopidogrel and 10.3% (n = 485) warfarin in the last two years. Analysis of medication history showed that 61% (n = 2,862) of people with CKD and Hb ≤ 11 g/dl had taken aspirin, three-quarters (73%, n = 3,422) NSAID, 14.1% (n = 662) were taking warfarin and 12.4% (n = 581) clopidogrel. Furthermore, more than half (55.6%, n = 999) of patients with iron deficiency anaemia and CKD stage 3–5 were concurrently prescribed NSAIDs and aspirin (Table 5).

Oral Iron prescription

Over half (62.6%) of people with anaemia in the general population had been prescribed oral iron therapy (Table 6) with prescriptions issued to a slightly lower proportion (56.3%) of people with anaemia and CKD. The commonest prescribed iron preparations were ferrous fumarate (322 mg bd) and ferrous sulphate (200 mg tid); with the prescriptions intended to provide 200 mg or 195 mg elemental iron, respectively; in line with current recommendations [50].

Two-thirds (67.6%) of people with anaemia and CKD and a low ferritin level were taking oral iron. The mean Hb in the iron treated group was 10.0 g/dl (n = 582) compared with 10.3 g/dl (n = 1214) in the non-iron treated (t-test p < 0.001).

Regression analysis

Stage 3–5 CKD was associated with a reduction in Hb, 0.712 g/dL (SE 0.017 g/dL, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.9%). The regression analysis testing each variable separately showed a small but significant effect of eGFR and CKD on the outcome variable, haemoglobin (B of 0.003, SE 0.000, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.2%). Our best model included: CKD stages 3–5, significant proteinuria, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, deprivation score and NSAID within last 2 years, R2 = 7.4% (p < 0.001). After adding other elements to the model the CKD remained a significant contributor to the final effect (Table 7); though overall the combined predictive effect of the model on anaemia is small (R2 = 7.7%). We excluded ACE-I from our final model. The unstandardised coefficient (B) was smaller than that for hypertension and the overall model performed less well with ACE-I and hypertension included.

Discussion

In this study we found that anaemia is common in CKD and usually normocytic. Anaemia in CKD is associated with a reduced ferritin in over half, suggesting depleted iron stores. Microcytic anaemia is less common, though over three-quarters of people with this type of anaemia have a reduced ferritin. All cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent among those with anaemia and CKD compared with those with a normal Hb and CKD. Over three-quarters of people with anaemia and CKD are on one or more medications which may exacerbate anaemia; over three quarters have been prescribed aspirin as some time, over two-thirds in the last two years. Nearly three quarters of anaemic people with CKD have been prescribed an NSAIDs. Three quarters of people with microcytic anaemia and over half of those with normocytic anaemia have been prescribed oral iron, however despite this their anaemia remains uncorrected. Stage 3–5 CKD and reduction in eGFR are weak but significant predictors of reduced haemoglobin.

The prevalence of anaemia increased with reduction of eGFR levels in all age groups and this observation corresponds, and appears to validate, in an independent sample findings in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) population [4, 5]. However, this prevalence is less than half that found in the more targeted National Kidney Foundation Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) [51].

Stage 3–5 CKD is an independent predictor variable of reduced haemoglobin. The current focus of UK National guidance on anaemia management in CKD needs to be reviewed. We recommend a shift from early referral to specialist centres for administration of parenteral iron or ESA to more effective medication management in primary care, with improved access to parenteral iron. Family physicians should carefully balance the risk benefit ratio of prescribing aspirin in cardiovascular disease and of NSAIDs in people with CKD. The concurrent use of acid suppressant therapy may help reduce the risk of gastrointestinal blood loss.

Our findings are consistent with a systematic review and meta-analysis that showed little benefit from oral iron in people with CKD. Interestingly, the rise in Hb reported using parenteral iron (0.83 g/dL) is similar to the decline seen in people with CKD (0.72 g/dL) [52].

In USA the Third National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey Public health (NHANES III) reported a high prevalence of anaemia, and a low ferritin in people with heart failure and CKD, which is also compatible with our results [53]. Likewise, NHANES found 42.2% (95% confidence interval 28.3-56.0%) of people with eGFR <40 ml/min were anaemic compared with 34% in this study. Antihypertensive medication, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are also associated with anaemia [14, 54]. We included hypertension, not anti-hypertensive therapy in our regression model. It is possible that the small reduction in haemoglobin associated with hypertension might be related to therapy.

Our approach is limited by the inevitable incompleteness of the routine data, though their strengths and weaknesses are well known [55]. The associations reported in this paper do not prove or imply a causative link; and paradoxically agents that might cause gastrointestinal haemorrhage were not associated with greater degrees of iron deficiency.

A further difficulty is that definitions of anaemia are not completely standardised. The European guidelines define anaemia as <11 g/dl [56], which is marginally different from guidance in England. The World Health Organization (WHO) define anaemia as <12 g/dl in women and <13 g/dl in men [57]. Whilst prescription of oral iron was not associated with correction of anaemia; we cannot conclude that it is ineffective as we don’t know the pre-treatment Hb levels. Although generally 200 mg of elemental iron is the default prescription in UK family practice, we know that it is common practice in primary care to advise patients to reduce the iron dose if they experience gastrointestinal side effects. We also only have evidence a prescription was issued, and nothing about what was actually dispensed.

Serum ferritin <100 ng/mL is used in this paper as a surrogate for iron deficiency; this is an expert consensus, used in UK national guidance [58] though many normal individuals having levels beneath this threshold [59].

Prospective studies are needed to assess whether more effective anaemia management strategies might reduce the incidence of CVD in people with CKD. Tools and algorithms are needed to help family doctors asses the relative risk of stopping NSAIDs, aspirin and other therapy against the potential benefits of correcting anaemia.

Conclusion

Anaemia is common among CKD patients in the UK and associated with cardiovascular diseases and prescription of drugs which may cause anaemia. Having stage 3–5 CKD is a predictor variable of a decline in haemoglobin. Primary care management should start with a careful medication review and assessment prior to referral for replacement of depleted iron stores with parenteral iron.

Abbreviations

- ACE-I:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- CEVD:

-

Cerebrovascular disease

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimate of glomerular filtration rate

- ESA:

-

Erthyropoiesis-stimulating agents

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- Hb:

-

Haemoglobin

- HT:

-

Hypertension

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- IHD:

-

Ischaemic heart disease

- IMD:

-

Index of multiple deprivation

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular mass index

- MCV:

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

- NHANES III:

-

Third National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey Public health

- PVD:

-

Peripheral vascular disease

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 18

- QICKD:

-

Quality Improvement in Chronic Kidney Disease

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, MacLellan WR, Borenstein J: Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 39 (11): 1780-1786. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01854-5.

Mozaffarian D, Nye R, Levy WC: Anemia predicts mortality in severe heart failure: the prospective randomized amlodipine survival evaluation (PRAISE). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 41 (11): 1933-1939. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00425-X.

Eckardt KU: Managing a fateful alliance: anaemia and cardiovascular outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005, 20 (Suppl 6): vi16-20.

Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace JA, Coresh J: Association of kidney function with anemia: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994). Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (12): 1401-1408. 10.1001/archinte.162.12.1401.

Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003, 41 (1): 1-12.

Valderrabano F, Horl WH, Macdougall IC, Rossert J, Rutkowski B, Wauters JP: PRE-dialysis survey on anaemia management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003, 18 (1): 89-100. 10.1093/ndt/18.1.89.

John R, Webb M, Young A, Stevens PE: Unreferred chronic kidney disease: a longitudinal study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004, 43 (5): 825-835. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.046.

Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group: Association between recombinant human erythropoietin and quality of life and exercise capacity of patients receiving haemodialysis. Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group. BMJ. 1990, 300 (6724): 573-578.

Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Mendelssohn D, Barre P, Takano T, Soroka S, Mujais S: Health-related quality of life and hemoglobin levels in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009, 4 (1): 33-38. 10.2215/CJN.00630208.

Harnett JD, Foley RN, Kent GM, Barre PE, Murray D, Parfrey PS: Congestive heart failure in dialysis patients: prevalence, incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Kidney Int. 1995, 47 (3): 884-890. 10.1038/ki.1995.132.

Walker AM, Schneider G, Yeaw J, Nordstrom B, Robbins S, Pettitt D: Anemia as a predictor of cardiovascular events in patients with elevated serum creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006, 17 (8): 2293-2298. 10.1681/ASN.2005020183.

Levin A, Thompson CR, Ethier J, Carlisle EJ, Tobe S, Mendelssohn D, Burgess E, Jindal K, Barrett B, Singer J, et al: Left ventricular mass index increase in early renal disease: impact of decline in hemoglobin. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999, 34 (1): 125-134. 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70118-6.

El-Achkar TM, Ohmit SE, McCullough PA, Crook ED, Brown WW, Grimm R, Bakris GL, Keane WF, Flack JM: Higher prevalence of anemia with diabetes mellitus in moderate kidney insufficiency: The Kidney Early Evaluation Program. Kidney Int. 2005, 67 (4): 1483-1488. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00226.x.

Ishani A, Weinhandl E, Zhao Z, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ, Yusuf S, Herzog CA: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor as a risk factor for the development of anemia, and the impact of incident anemia on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45 (3): 391-399. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.038.

de Lusignan S: An educational intervention, involving feedback of routinely collected computer data, to improve cardiovascular disease management in UK primary care. Methods Inf Med. 2007, 46 (1): 57-62.

Maddux FW, Shetty S, del Aguila MA, Nelson MA, Murray BM: Effect of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on healthcare utilization, costs, and outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2007, 41 (11): 1761-1769. 10.1345/aph.1K194.

Anderson J, Glynn LG, Newell J, Iglesias AA, Reddan D, Murphy AW: The impact of renal insufficiency and anaemia on survival in patients with cardiovascular disease: a cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009, 9: 51-10.1186/1471-2261-9-51.

Parfrey PS, Lauve M, Latremouille-Viau D, Lefebvre P: Erythropoietin therapy and left ventricular mass index in CKD and ESRD patients: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009, 4 (4): 755-762. 10.2215/CJN.02730608.

Goldberg N, Lundin AP, Delano B, Friedman EA, Stein RA: Changes in left ventricular size, wall thickness, and function in anemic patients treated with recombinant human erythropoietin. Am Heart J. 1992, 124 (2): 424-427. 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90608-X.

Wish JB, Nassar GM, Schulman K, del Aguila M, Provenzano R: Postdialysis outcomes associated with consistent anemia treatment in predialysis patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2008, 69 (4): 251-259.

Foley RN, Curtis BM, Parfrey PS: Hemoglobin targets and blood transfusions in hemodialysis patients without symptomatic cardiac disease receiving erythropoietin therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008, 3 (6): 1669-1675. 10.2215/CJN.02100508.

Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Yoshida H, Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O: Reversal of anemia by erythropoietin therapy retards the progression of chronic renal failure, especially in nondiabetic patients. Nephron. 1997, 77 (2): 176-185. 10.1159/000190270.

Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Blum M, Keren G, Sheps D, Leibovitch E, Brosh D, Laniado S, Schwartz D, Yachnin T, et al: The use of subcutaneous erythropoietin and intravenous iron for the treatment of the anemia of severe, resistant congestive heart failure improves cardiac and renal function and functional cardiac class, and markedly reduces hospitalizations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 35 (7): 1737-1744. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00613-6.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Anaemia Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Rapid Update 2011. Clinical Guideline. Methods, evidence and recommendations. CG114. [http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13329/52851/52851.pdf]

Clinical practice guidelines. Anaemia in CKD. [http://www.renal.org/Clinical/GuidelinesSection/AnaemiaInCKD.aspx]

Mancini DM, Katz SD, Lang CC, LaManca J, Hudaihed A, Androne AS: Effect of erythropoietin on exercise capacity in patients with moderate to severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003, 107 (2): 294-299. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000044914.42696.6A.

Tehrani F, Dhesi P, Daneshvar D, Phan A, Rafique A, Siegel RJ, Cercek B: Erythropoiesis stimulating agents in heart failure patients with anemia: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2009, 23 (6): 511-518. 10.1007/s10557-009-6203-6.

Ghali JK, Anand IS, Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Greenberg B, Krum H, Massie BM, Wasserman SM, Trotman ML, Sun Y, et al: Randomized double-blind trial of darbepoetin alfa in patients with symptomatic heart failure and anemia. Circulation. 2008, 117 (4): 526-535. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698514.

Desai A, Lewis E, Solomon S, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer M: Impact of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure: an updated, post-TREAT meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010, 12 (9): 936-942. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq094.

Singh AK: The controversy surrounding hemoglobin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: what should we do now?. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008, 52 (6 Suppl): S5-13.

FDA modifies dosing recommendations for Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents. [http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm260670.htm]

de Lusignan S, Gallagher H, Chan T, Thomas N, van Vlymen J, Nation M, Jain N, Tahir A, du Bois E, Crinson I, et al: The QICKD study protocol: a cluster randomised trial to compare quality improvement interventions to lower systolic BP in chronic kidney disease (CKD) in primary care. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 39-10.1186/1748-5908-4-39.

de Lusignan S, Gallagher H, Jones S, Chan T, van Vlymen J, Tahir A, Thomas N, Jain N, Dmitrieva O, Rafi I, et al: Using audit-based education to lower systolic blood pressure in chronic kidney disease (CKD): results of the quality improvement in CKD (QICKD) trial [ISRCTN: 56023731]. Accepted for Publication Kidney International, 13th January 2013, Ref: KI-06-12-0863.R3

van Vlymen J, de Lusignan S, Hague N, Chan T, Dzregah B: Ensuring the quality of aggregated general practice data: lessons from the primary care data Quality Programme (PCDQ). Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005, 116: 1010-1015.

van Vlymen J, de Lusignan S: A system of metadata to control the process of query, aggregating, cleaning and analysing large datasets of primary care data. Inform Prim Care. 2005, 13 (4): 281-291.

Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): Measure of multiple deprivation at small area level made up of seven domains. [http://data.gov.uk/dataset/imd_2004]

de Lusignan S, Tomson C, Harris K, van Vlymen J, Gallagher H: Creatinine fluctuation has a greater effect than the formula to estimate glomerular filtration rate on the prevalence of chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011, 117 (3): c213-224. 10.1159/000320341.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): Chronic kidney disease. National clinical guideline for early identification and management in adults in primary and secondary care (Clinical Guideline 73). [http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12069/42117/42117.pdf]

de Lusignan S, Tomson C, Harris K, van Vlymen J, Gallagher H: Creatinine fluctuation has a greater effect than the formula to estimate glomerular filtration rate on the prevalence of chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010, 117 (3): c213-c224.

Bessman JD, Johnson RK: Erythrocyte volume distribution in normal and abnormal subjects. Blood. 1975, 46 (3): 369-379.

Agarwal AK: Practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of anemia associated with CKD in elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006, 7 (9 Suppl): S7-S12. quiz S17-21

Grabe DW: Update on clinical practice recommendations and new therapeutic modalities for treating anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007, 64 (13 Suppl 8): S8-14. quiz S23-15

Stancu S, Stanciu A, Zugravu A, Barsan L, Dumitru D, Lipan M, Mircescu G: Bone marrow iron, iron indices, and the response to intravenous iron in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010, 55 (4): 639-647. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.043.

Smellie WS, Forth J, Bareford D, Twomey P, Galloway MJ, Logan EC, Smart SR, Reynolds TM, Waine C: Best practice in primary care pathology: review 3. J Clin Pathol. 2006, 59 (8): 781-789. 10.1136/jcp.200X.033944.

Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, Scott BB: Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2011

Bowling CB, Inker LA, Gutierrez OM, Allman RM, Warnock DG, McClellan W, Muntner P: Age-specific associations of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate with concurrent chronic kidney disease complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011, 6 (12): 2822-2828. 10.2215/CJN.06770711.

Michalakidis G, Kumarapeli P, Ring A, van Vlymen J, Krause P, de Lusignan S: A system for solution-orientated reporting of errors associated with the extraction of routinely collected clinical data for research and quality improvement. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010, 160 (Pt 1): 724-728.

de Lusignan S, Chan T, Stevens P, O'Donoghue D, Hague N, Dzregah B, Van Vlymen J, Walker M, Hilton S: Identifying patients with chronic kidney disease from general practice computer records. Fam Pract. 2005, 22 (3): 234-241. 10.1093/fampra/cmi026.

Comparing intervention to lower systolic blood pressure in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a Cluster Randomised Trial (CRT). ISRCTN56023731. [http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN56023731/56023731]

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO): Clinical Practice Guideline for anaemia in chronic disease. Kidney International. 2012, 2: 282-10.1038/kisup.2012.40.

McFarlane SI, Chen SC, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR, Vassalotti JA, Salifu MO, Li S, Wang C, Bakris G, McCullough PA, Kidney Early Evaluation Program Investigators, et al: Prevalence and associations of anemia of CKD: Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008, 51 (4 Suppl 2): S46-55. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.019.

Rozen-Zvi B, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici L, Shpilberg O, Gafter U: Intravenous versus oral iron supplementation for the treatment of anemia in CKD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008, 52 (5): 897-906. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.033.

Clase CM, Kiberd BA, Garg AX: Relationship between glomerular filtration rate and the prevalence of metabolic abnormalities: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Nephron Clin Pract. 2007, 105 (4): c178-184. 10.1159/000100489.

Albitar S, Genin R, Fen-Chong M, Serveaux MO, Bourgeon B: High dose enalapril impairs the response to erythropoietin treatment in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998, 13 (5): 1206-1210. 10.1093/ndt/13.5.1206.

de Lusignan S, van Weel C: The use of routinely collected computer data for research in primary care: opportunities and challenges. Fam Pract. 2006, 23 (2): 253-263.

CPR 1.1. Identifying patients and initiating evaluation II. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease in adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006, 47 (5 Suppl 3): S16-85.

Iron deficiency anaemia. Assessment, prevention and control. A guide for programme managers. [http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/anaemia_iron_deficiency/WHO_NHD_01.3/en/]

Mikhail A, Shrivastava R, Richardson D: Clinical practice guidelines, Anaemia of CKD. UK Renal Association, 2009-2012. URL: http://www.renal.org/Libraries/Guidelines/Anaemia_in_CKD_Draft_Version_-_15_February_2010.sflb.ashx, 5

Wish JB: Assessing iron status: beyond serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006, 1 (Suppl 1): S4-8.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/14/24/prepub

Acknowledgments

Patients, clinicians and staff of the data contributing practices. Health Foundation for funding the QICKD trial. Collaborators in the QICKD trial include Kidney Research UK. Antonios Ntasioudis, Jeremy van Vlymen, University of Surrey, and Andre Ring, St. George’s. Georgios Michalakidis and Nigel Mehdi for assistance with the data repository. Tara Bader for initial analysis contributing to Figure 2 and Chris Pearce for his comments on the manuscript.

Financial disclosure

Health Foundation - funding of travel related to the study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

OD: None. SdeL: Involved in development of the pay-for-performance indicator for UK practice; lead author for Department of Health Frequently Asked Questions about chronic kidney disease. http://www.nhsemployers.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Chronic_kidney_disease_FAQs%20-%20ja040711.pdf. IMacD: Professor Macdougall has received consultancy and lecture honoraria from several companies involved in the manufacture of ESAs and IV iron products, and is a current Work Group member of the KDIGO Anemia Guidelines Group. HG: None. CT: None. KH: Kevin Harris has received funding from several pharmaceutical companies, Edith Murphy Foundation 2007–2010: Quality Improvement in CKD due to diabetes and LNR CLAHRC for Prevention of Chronic Disease and its Associated Co-Morbidity theme. TD: None. DG: Honoraria and Speaker Fees from Takeda, Roche, Sandoz, Amgen.

Authors’ contributions

OD, SdeL, ICM and DG conceived and designed the study; OD wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which SDEL developed. OD and SDEL performed the analysis. OD, SdeL, ICM, HG, CT, KH, TD and DG. All authors contributed to editing the paper, and approved the final version of the paper.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dmitrieva, O., de Lusignan, S., Macdougall, I.C. et al. Association of anaemia in primary care patients with chronic kidney disease: cross sectional study of quality improvement in chronic kidney disease (QICKD) trial data. BMC Nephrol 14, 24 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-24

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-24