Abstract

Background

There is a substantial genetic component for birthweight variation, and although there are known associations between fetal genotype and birthweight, the role of common epigenetic variation in influencing the risk for small for gestational age (SGA) is unknown. The two imprinting control regions (ICRs) located on chromosome 11p15.5, involved in the overgrowth disorder Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) and the growth restriction disorder Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS), are prime epigenetic candidates for regulating fetal growth. We investigated whether common variation in copy number in the BWS/SRS 11p15 region or altered methylation levels at IGF2/H19 ICR or KCNQ10T1 ICR was associated with SGA.

Methods

We used a methylation-specific multiplex-ligation-dependent probe amplification assay to analyse copy number variation in the 11p15 region and methylation of IGF2/H19 and KCNQ10T1 ICRs in blood samples from 153 children (including 80 SGA), as well as bisulfite pyrosequencing to measure methylation at IGF2 differentially methylated region (DMR)0 and H19 DMR.

Results

No copy number variants were detected in the analyzed cohort. Children born SGA had 2.7% lower methylation at the IGF2 DMR0. No methylation differences were detected at the H19 or KCNQ10T1 DMRs.

Conclusions

We confirm that a small hypomethylation of the IGF2 DMR0 is detected in peripheral blood leucocytes of children born SGA at term. Copy number variation within the 11p15 BWS/SRS region is not an important cause of non-syndromic SGA at term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Term infants born small for gestational age (SGA) have high rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality [1] as well as increased risk of later-life chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity and hypertension [2]. Birth weight variation has a significant genetic component with clustering of SGA births in families and recurrence in successive generations [3, 4], and heritability estimates from family and twin studies range between 25-40% [5]. Recent data from genome wide association studies have found robust associations between fetal genotype and birth weight [6], and we have previously demonstrated that genetic variation in certain genes associated with obesity and or type 2 diabetes is more prevalent in those born SGA than those born appropriate for gestational age (AGA) [7]. Currently, little is known about the role of epigenetic modifications and copy number variation in determining the risk of SGA.

The term epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression that are not encoded by alterations within the DNA sequence and includes, non-coding RNAs, methylation of DNA and a range of histone modifications. The IGF2/H19 and KCNQ10T1 imprinting control regions (ICRs) are strong candidates for the epigenetic influence on birth weight variation as they are implicated in the neonatal overgrowth and growth restriction conditions of Beckwith Wiedemann (BWS) and Silver-Russell (SRS) syndromes, respectively. Severe hypomethylation of the KCNQ10T1 ICR [8] and hypermethylation of the H19 DMR is found in 50% and 10% of BWS cases, respectively [9]. Conversely, severe hypomethylation of the H19 DMR or IGF2 DMR on the paternal allele (associated with IGF2 repression) is found in over 50% of patients with Silver-Russell Syndrome [10], characterized by intrauterine and post-natal growth retardation [11]. Copy number variation through uniparental disomy and small deletions or duplications affecting both these regulatory sites are also recognised causes of BWS and SRS [12]. Maternal duplication of this region is associated with growth retardation [13, 14], while paternal duplication is associated with overgrowth at birth [8].

The IGF2/H19 ICR contains several differentially methylated regions (DMRs), which are all predominantly methylated on the paternally inherited allele: the IGF2 DMR0 (located between exons 2 and 3 of IGF2), the IGF2 DMR2 (between exons 8 and 9) and the H19 DMR, located 4 kb upstream of the transcription start of H19[15], which are all methylated to a level of 40-50% [10, 16, 17]. The methylation status of the IGF2 DMR0 is more likely to be indicative of changes in IGF2 transcription from the active allele given it has been suggested to possess promoter activity [18]. The H19 DMR contains several recognition sites for the CCCTC binding factor (CTCF), which binds to these sites on the maternal allele to form a chromatin boundary which blocks IGF2 transcription and promotes H19 transcription from the maternal allele. CTCF cannot bind to the paternal allele, which is methylated at these sites, bringing enhancers downstream of H19 in close proximity to the IGF2 gene, enhancing its transcription, while H19 is not expressed from the paternal allele. The KCNQ10T1 ICR (also called KvDMR1) within intron 10 of KCNQ1 is maternally methylated, and regulates the maternally expressed CDKN1C gene and the paternally expressed but untranslated protein KCNQ10T1 [19].

Two studies using bisulfite pyrosequencing to investigate the IGF2 and H19 DMRs in cord blood have found either no association [20] or a minor (1.6%) reduction in the methylation levels of the IGF2 DMR0 [21] among infants born with low birthweight, but not necessarily at term. One previous study analyzing 19 children conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection and born small for gestational age (SGA), found that one child had a clear hypermethylation of KCNQ10T1 with a methylation level of 74% [22]. Copy number variations in several growth related genes including IGF2 but not CDKN1C or KCNQ10T1 were examined in 100 SGA children with short stature, and although no IGF2 deletions were found, two children were identified with IGF1R haploinsufficiency [23].

The aim of our study was therefore to investigate whether in the absence of assisted reproduction, common epigenetic variation (loss of methylation at the IGF2/H19 ICR or gain of methylation at the KCNQ10T1 ICR) or copy number variation (causing maternal duplication of the 11p15 region) are associated with the phenotype of SGA at term.

Methods

Participants

The Auckland Birthweight Collaborative (ABC) study has been previously described in detail [24]. In summary, from the original cohort of singleton babies without congenital abnormalities or assisted reproduction, born at term (37+ weeks gestation), and resident in Auckland in 1995–1997, all those of European ethnicity who were followed up at 11 years, and consented to analysis of DNA from a blood sample were included in this study. Written informed consent was obtained for genetic analysis, from the parent or guardian on behalf of the children enrolled in the study. The Northern X ethics committee approved the study. Samples from 153 children were available for this study, including 81 born SGA (≤10th percentile corrected for sex and gestational age).

Molecular genetic analysis

DNA was extracted from blood samples using the DNA extraction kit from Qiagen. All samples were extracted at the same time. The methylation status of the H19 and KCNQ10T1 ICRs was investigated by multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification (MLPA) using the SALSA MLPA ME030-B1 BWS/SRS kit (lot 0208) purchased from MRC-Holland (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). This mix includes 26 probes specific for the BSW/SRS 11p15 region of which 11 probes contain a recognition site for the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease HhaI and can thereby provide information about the methylation status of the target sequence, including five within the H19 DMR, and 5 within the KCNQ10T1 DMR. The kit also contains additional 16 probes that are used as controls for copy number quantification and 4 control probes for complete HhaI digestion. MLPA analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol and has been previously described [25]. In brief, 100 ng of genomic DNA from each individual was denatured and hybridized overnight with the probe mixture supplied with the kit, and then, after dividing the sample into two aliquots, treated either with ligase alone or with ligase and HhaI. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions were performed with the primers supplied in the kit. Once microlitre of each PCR product was mixed with 0.5 μL of Genescan-Rox 500 size standard and 8.5 μL of deionised formamide, and 1 μL was injected into a 36 cm capillary (model 3130XL, Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA). Electropherograms were analyzed using the Genescan software. Non-SGA samples were run as reference at the same time as SGA samples to ensure comparability and avoid any batch effects.

The quality of raw data was evaluated according to the manufacturer’s checklist (MRC Holland). For each sample the relative area under the peak was calculated using the Coffalyser software (version 9.4). First, data from digested and undigested probes were used to perform intra-sample normalization whereby the signal for each investigated probe was divided by the signal of all reference probes within the sample. The median of all ratios was used as a normalization constant for subsequent analysis. Next, the copy number in undigested samples was determined by dividing the normalisation constant of each probe of each patient sample by the average normalisation constant of all reference samples for that probe. The methylation level was obtained by dividing each normalization constant of the digested sample by the normalization constant of the corresponding undigested sample. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean of the standard deviations of the methylation ratios in each patient was 0.03 for the H19 DMR and 0.02 for KCNQ10T1, respectively (ranges 0.02-0.06 and 0.01-0.03 respectively) as previously reported [26].

In addition, a subset of 58 samples (43 born SGA) was investigated using bisulfite pyrosequencing. 500 ng genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite using the EpiTect Bisulfite conversion kit (Qiagen) and 50 ng of this DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification. Two DMRs were analyzed by pyrosequencing as previously described: the IGF2 DMR0 (3 CpGs), and in the 3rd CTCF binding site of the H19 DMR (11 CpGs) [27]. Accession numbers and nucleotide positions of each DMR, PCR primers and annealing temperatures as well as the size of PCR products have been previously described [28].

The MLPA methylation analysis investigated five sites within the H19 DMR. HhaI ligation sites analyzed with reference to the Genbank sequence AF125183.1 were: 9769–9770 (H19a); 9605–9606 (H19b), 9449–9450 (H19c), 9144–9145 (H19d), 8691–8692 (H19e). The five HhaI ligation sites within the KCNQ10T1 DMR were with respect to Genank AJ006345.1: 254373–254374 (KCNQ10T1a); 254444–254445 (KCNQ10T1b), 254890–254891 (KCNQ10T1c), 255226–255227 (KCNQ10T1d), 333007–333008 (KCNQ10T1e). Pyrosequencing was used to analyse 11 CpG sites within CTCF3 of the H19 DMR and 3 CpGs within the IGF2 DMR0.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the population were described as mean and SD for birthweight. We used t-tests to assess the difference in the mean methylation levels of the H19 DMR, KCNQ10T1 DMR, IGF2 DMR0 and CTCF3 between the SGA and AGA groups. Statistical significance was defined at the 5% level.

Results

No copy number variations within any of the 11p15 genes involved in BWS or SRS were detected. One child was found to have markedly reduced methylation at all probe locations within the KCNQ10T1 DMR, (reported separately in [29]), and was excluded from this analysis.

There was no significant difference in the methylation levels within the H19 DMR or KCNQ10T1 DMR between children born SGA compared to non-SGA using MLPA (Table 1). When we analysed the subset who had pyrosequencing analysis, there was no significant difference in the mean methylation levels at CTCF3. However, the DNA methylation level at CpG1 of the IGF2 DMR0 was statistically significant lower (2.7%) among cildren born SGA compared to those born AGA (SGA mean [sd] 44.1 [3.8] vs 47.2 [3.8], p = 0.009). However, no difference was observed at the other two CpG sites (Table 1).

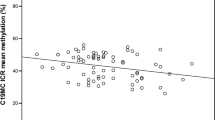

Figure 1 shows the correlation of all the methylation sites examined. DNA methylation of the five different HhaI ligation sites within KCNQ10T1 was poorly correlated (range −0.23 to 0.46). DNA methylation of the 5 HhaI ligation sites within the H19 DMR was also poorly correlated (range −0.17 to 0.25). Correlation between the 11 different CpG sites of the CTCF3 site within the H19 DMR region interrogated by pyrosequencing was moderate (r = 0.49 range (0.16 to 0.83)). The correlation between the 3 CpG sites within the IGF2 DMR0 was relatively weak (mean r = 0.30 (range −0.02 to 0.54)).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined whether SGA at term was associated with copy number variation or altered methylation levels at two imprinted genetic loci (H19 DMR, IGF2 DMR0 and KCNQ10T1 DMR) known to be associated with SRS or BWS on chromosome 11p15.5. We found a statistically significant 2.7% reduction in methylation at IGF2 DMR0 in peripheral blood leucocytes collected from 11 year old children born SGA compared to those born AGA. This association would not have reached the level of statistical significance after correction for multiple testing, and we cannot exclude that this result occurred by chance. However, our result is consistent with a previous study which reported 1.6% lower methylation at the same IGF2 DMR0 using cord blood DNA from infants born with low birthweight [21]. We did not find any copy number variation.

We used a commercially available MLPA kit, which enabled simultaneous interrogation of copy number and methylation status of multiple loci relevant to BWS/SRS. We observed little correlation between the non-contiguous methylation sites interrogated either by MLPA or pyrosequencing methods. Although we did not expect any correlation between H19 DMR, IGF2 DMR0 and the more centromeric KCNQ10T1 DMR which are two distinct imprinting domains, we also observed little correlation between the 5 MLPA sites within the H19 DMR. We observed little correlation between the H19 sites interrogated by MLPA, and either the CTCF3 or the IGF2 DMR0 CpGs interrogated by pyrosequencing.

Although the MLPA method for detecting BWS and SRS abnormalities has been demonstrated to have good intra-assay and inter-assay reproducability [26], this method may have limited sensitivity to detect minor variation in methylation levels. However, selective hypomethylation for either the H19 DMR or the IGF2 DMR0 has been previously reported in patients with SRS [30]. Selective hypomethylation of the IGF2 DMR0 but not the H19 DMR has previously been associated with lower birthweight [21], and the converse for maternal folic acid intake [20].

Conclusion

This study confirms minor hypomethylation of the IGF2 DMR0 in peripheral blood leucocytes of children born SGA at term, which is not reflected at other imprinted sites within the IGF2/H19 domain. Copy number variation within the 11p15 BWS/SRS region does not seem to be an important cause of non-syndromic SGA at term.

Abbreviations

- BWS:

-

Beckwith Wiedemann Syndrome

- CTCF:

-

CCCTC-binding factor

- DMR:

-

Differentially methylated region

- ICR:

-

Imprinting control region

- MLPA:

-

Multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- SRS:

-

Silver-Russell syndrome.

References

Hay WW, Catz CS, Grave GD, Yaffe SJ: Workshop summary: fetal growth: its regulation and disorders. Pediatrics. 1997, 99 (4): 585-591.

Gillman MW, Barker D, Bier D, Cagampang F, Challis J, Fall C, Godfrey K, Gluckman P, Hanson M, Kuh D, Nathanielsz P, Nestel P, Thornburg KL: Meeting report on the 3rd International Congress on Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). Pediatr Res. 2007, 61 (5 Pt 1): 625-629.

Ananth CV, Kaminsky L, Getahun D, Kirby RS, Vintzileos AM: Recurrence of fetal growth restriction in singleton and twin gestations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009, 22 (8): 654-661.

Selling KE, Carstensen J, Finnstrom O, Sydsjo G: Intergenerational effects of preterm birth and reduced intrauterine growth: a population-based study of Swedish mother-offspring pairs. BJOG. 2006, 113 (4): 430-440.

Clausson B, Lichtenstein P, Cnattingius S: Genetic influence on birthweight and gestational length determined by studies in offspring of twins. BJOG. 2000, 107 (3): 375-381.

Freathy RM, Mook-Kanamori DO, Sovio U, Prokopenko I, Timpson NJ, Berry DJ, Warrington NM, Widen E, Hottenga JJ, Kaakinen M, Lange LA, Bradfield JP, Kerkhof M, Marsh JA, Mägi R, Chen CM, Lyon HN, Kirin M, Adair LS, Aulchenko YS, Bennett AJ, Borja JB, Bouatia-Naji N, Charoen P, Coin LJ, Cousminer DL, de Geus EJ, Deloukas P, Elliott P, Evans DM, et al: Variants in ADCY5 and near CCNL1 are associated with fetal growth and birth weight. Nat Genet. 2010, 42 (5): 430-435.

Morgan AR, Thompson JM, Murphy R, Black PN, Lam WJ, Ferguson LR, Mitchell EA: Obesity and diabetes genes are associated with being born small for gestational age: results from the Auckland Birthweight Collaborative study. BMC Med Genet. 2010, 11: 125-

Weksberg R, Smith A, Squire J, Sadowski PD: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome demonstrates a role for epigenetic control of normal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12: 61-68.

Weksberg R, Smith AC, Squire J, Sadowski P: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome demonstrates a role for epigenetic control of normal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12 (Spec No 1): R61-R68.

Gicquel C, Rossignol S, Cabrol S, Houang M, Steunou V, Barbu V, Danton F, Thibaud N, Le Merrer M, Burglen L, Bertrand AM, Netchine I, Le Bouc Y: Epimutation of the telomeric imprinting center region on chromosome 11p15 in Silver-Russell syndrome. Nat Genet. 2005, 37 (9): 1003-1007.

Eggermann T: Silver-Russell and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndromes: opposite (epi)mutations in 11p15 result in opposite clinical pictures. Horm Res. 2009, 71 (Suppl 2): 30-35.

Eggermann T, Begemann M, Binder G, Spengler S: Silver-Russell syndrome: genetic basis and molecular genetic testing. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010, 5: 19-

Fisher A, Thomas N, Cockwell A, Stecko O, Kerr B, Temple IK, Clayton P: Duplications of chromosome 11p15 of maternal origin result in a phenotype that includes growth retardation. Hum Genet. 2002, 111: 290-296.

Schonherr N, Meyer E, Roos A, Schmidt A, Wollmann HA, Eggermann T: The centromeric 11p15 imprinting centre is also involved in Silver-Russell syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007, 44 (1): 59-63.

Murrell A, Heeson S, Reik W: Interaction between differentially methylated regions partitions the imprinted genes Igf2 and H19 into parent-specific chromatin loops. Nat Genet. 2004, 36 (8): 889-893.

Ito Y, Koessler T, Ibrahim AE, Rai S, Vowler SL, Abu-Amero S, Silva AL, Maia AT, Huddleston JE, Uribe-Lewis S, Woodfine K, Jagodic M, Nativio R, Dunning A, Moore G, Klenova E, Bingham S, Pharoah PD, Brenton JD, Beck S, Sandhu MS, Murrell A: Somatically acquired hypomethylation of IGF2 in breast and colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17 (17): 2633-2643.

Guo L, Choufani S, Ferreira J, Smith A, Chitayat D, Shuman C, Uxa R, Keating S, Kingdom J, Weksberg R: Altered gene expression and methylation of the human chromosome 11 imprinted region in small for gestational age (SGA) placentae. Dev Biol. 2008, 320 (1): 79-91.

Monk D, Sanches R, Arnaud P, Apostolidou S, Hills FA, Abu-Amero S, Murrell A, Friess H, Reik W, Stanier P, Constância M, Moore GE: Imprinting of IGF2 P0 transcript and novel alternatively spliced INS-IGF2 isoforms show differences between mouse and human. Hum Mol Genet. 2006, 15 (8): 1259-1269.

Mitsuya K, Meguro M, Lee MP, Katoh M, Schulz TC, Kugoh H, Yoshida MA, Niikawa N, Feinberg AP, Oshimura M: LIT1, an imprinted antisense RNA in the human KvLQT1 locus identified by screening for differentially expressed transcripts using monochromosomal hybrids. Hum Mol Genet. 1999, 8 (7): 1209-1217.

Hoyo C, Fortner K, Murtha AP, Schildkraut JM, Soubry A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Jirtle RL, Kurtzberg J, Forman MR, Overcash F, Huang Z, Murphy SK: Association of cord blood methylation fractions at imprinted insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), plasma IGF2, and birth weight. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23 (4): 635-645.

Liu Y, Murphy SK, Murtha AP, Fuemmeler BF, Schildkraut J, Huang Z, Overcash F, Kurtzberg J, Jirtle R, Iversen ES, Forman MR, Hoyo C: Depression in pregnancy, infant birth weight and DNA methylation of imprint regulatory elements. Epigenetics. 2012, 7 (7): 735-746.

Kanber D, Buiting K, Zeschnigk M, Ludwig M, Horsthemke B: Low frequency of imprinting defects in ICSI children born small for gestational age. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009, 17 (1): 22-29.

Ester WA, van Duyvenvoorde HA, de Wit CC, Broekman AJ, Ruivenkamp CA, Govaerts LC, Wit JM, Hokken-Koelega AC, Losekoot M: Two short children born small for gestational age with insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor haploinsufficiency illustrate the heterogeneity of its phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94 (12): 4717-4727.

Thompson JM, Clark PM, Robinson E, Becroft DM, Pattison NS, Glavish N, Pryor JE, Wild CJ, Rees K, Mitchell EA: Risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies: the Auckland birthweight collaborative study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001, 37 (4): 369-375.

Eggermann K, Schonherr N, Ranke MB, Wollmann HA, Binder G, Eggermann T: Search for subtelomeric imbalances by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification in Silver-Russell syndrome. Genet Test. 2008, 12 (1): 111-113.

Scott RH, Douglas J, Baskcomb L, Nygren AO, Birch JM, Cole TR, Cormier-Daire V, Eastwood DM, Garcia-Minaur S, Lupunzina P, Tatton-Brown K, Bliek J, Maher ER, Rahman N: Methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA) robustly detects and distinguishes 11p15 abnormalities associated with overgrowth and growth retardation. J Med Genet. 2008, 45 (2): 106-113.

Tost J, Gut IG: DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007, 2 (9): 2265-2275.

Dejeux E, Olaso R, Dousset B, Audebourg A, Gut IG, Terris B, Tost J: Hypermethylation of the IGF2 differentially methylated region 2 is a specific event in insulinomas leading to loss-of-imprinting and overexpression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009, 16 (3): 939-952.

Murphy R, Mackay D, Mitchell EA: Beckwith Wiedemann imprinting defect found in leucocyte but not buccal DNA in a child born small for gestational age. BMC Med Genet. 2012, 13: 99-

Bartholdi D, Krajewska-Walasek M, Ounap K, Gaspar H, Chrzanowska KH, Ilyana H, Kayserili H, Lurie IW, Schinzel A, Baumer A: Epigenetic mutations of the imprinted IGF2-H19 domain in Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS): results from a large cohort of patients with SRS and SRS-like phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2009, 46 (3): 192-197.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/15/67/prepub

Acknowledgements

The epigenetic component of this study was funded by the Faculty of Research and Development fund of the University of Auckland and NovoNordisk NZ Diabetes Grant Scheme. We acknowledge Wen-Jiun Lam for performing the DNA extraction and Pak-Cheung Tong for performing the MLPA assays with analysis assistance from Carey-Anne Eddy and Galina Konechyva, with kind permission from Professors Lynn Ferguson, Jill Cornish, and Andrew Shelling.

The ABC Study group also includes Dr David Becroft, Dr Karen Waldie, Professor Chris Wild, Dr Clare Wall and the late Professor Peter Black. Ed Mitchell and John Thompson are supported by Cure Kids.

The initial ABC study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The 12 month postal questionnaire was funded by Hawkes Bay Medical Research Foundation. The 3.5 year follow-up study was funded by Child Health Research Foundation, Becroft foundation and Auckland Medical Research foundation. The 7 year follow-up study was funded by Child health Research foundation. The 11 year follow-up study was funded by Child Health Research Foundation and the Heart Foundation. We acknowledge the assistance of Gail Gillies, Barbara Rotherham and Helen Nagels for contacting or assessing the participants. The children were assessed at the Starship Children’s Research Centre, which is supported in part by the Starship Foundation and Auckland District Health Board. We sincerely thank the parents and children for participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

RM conceived the study, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. JT acquired the pyrosequencing data and assisted with data interpretation. JMDT performed the statistical analysis of all genetic data. EM contributed to interpretation of data. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, R., Thompson, J.M., Tost, J. et al. No evidence for copy number and methylation variation in H19 and KCNQ10T1 imprinting control regions in children born small for gestational age. BMC Med Genet 15, 67 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-15-67

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-15-67