Abstract

Background

Conflicting results currently exist on the effects of LDL-C levels and statins therapy on coronary atherosclerotic plaque, and the target level of LDL-C resulting in the regression of the coronary atherosclerotic plaques has not been settled.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were searched from Jan. 2000 to Jan. 2014 for randomized controlled or blinded end-points trials assessing the effects of LDL-C lowering therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque (CAP) in patients with coronary heart disease by intravascular ultrasound. Data concerning the study design, patient characteristics, and outcomes were extracted. The significance of plaques regression was assessed by computing standardized mean difference (SMD) of the volume of CAP between the baseline and follow-up. SMD were calculated using fixed or random effects models.

Results

Twenty trials including 5910 patients with coronary heart disease were identified. Mean lowering LDL-C by 45.4% and to level 66.8 mg/dL in the group of patients with baseline mean LDL-C 123.7 mg/dL, mean lowering LDL-C by 48.8% and to level 60.6 mg/dL in the group of patients with baseline mean LDL-C 120 mg/dL, and mean lowering LDL-C by 40.4% and to level 77.8 mg/dL in the group of patients with baseline mean LDL-C 132.4 mg/dL could significantly reduce the volume of CAP at follow up (SMD −0.108 mm3, 95% CI −0.176 ~ −0.040, p = 0.002; SMD −0.156 mm3, 95% CI −0.235 ~ −0.078, p = 0.000; SMD −0.123 mm3, 95% CI −0.199 ~ −0.048, p = 0.001; respectively). LDL-C lowering by rosuvastatin (mean 33 mg daily) and atorvastatin (mean 60 mg daily) could significantly decrease the volumes of CAP at follow up (SMD −0.162 mm3, 95% CI: −0.234 ~ −0.081, p = 0.000; SMD −0.101, 95% CI: −0.184 ~ −0.019, p = 0.016; respectively). The mean duration of follow up was from 17 ~ 21 months.

Conclusions

Intensive lowering LDL-C (rosuvastatin mean 33 mg daily and atorvastatin mean 60 mg daily) with >17 months of duration could lead to the regression of CAP, LDL-C level should be reduced by >40% or to a target level <78 mg/dL for regressing CAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is universally accepted that high serum concentrations of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) can lead to atherosclerosis and accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis which is main causes of coronary artery disease [1]. Disruption of coronary atherosclerotic plaque (CAP) with subsequent thrombus formation may lead to sudden cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, or unstable angina [2]. The evidence showed that reducing LDL-C can prevent coronary heart disease (CHD) and improve survival of CHD based on results from multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [3, 4].

For many years coronary angiography (CAG) has been the gold standard method for the investigation of the anatomy of coronary arteries and measure the efficacy of anti-atherosclerotic drug therapies [5, 6]. But changes in CAG are measured only in the vascular lumen and not in the vessel wall [7], where the atherosclerotic process is located. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is superior to angiography in the detection of early plaque formation and changes in plaque volume [8–10]. Through IVUS, Takagi et al. found that pravastatin lowered serum cholesterol levels and reduced the progression of CAP in patients with elevated serum cholesterol levels in 1997 [11]. Since then, multiple RCTs and no RCT about the effect of lowering LDL-C therapy on the regression of coronary atherosclerosis have been performed [12–16]. But the results varied with the RCTs: intensive LDL-C lowering therapy could reduce the progression of the plaques [12]; the mild LDL-C lowering did not [14–16]. The meta-analysis by Bedi et al. [17] evaluated the effects of LDL-C lowering on CAP by comparing statins with control therapy, and demonstrated that treatment with statins could slow atherosclerotic plaque progression and lead to plaque regression. The meta-analysis by Tian et al. [18] showed that CAP could be regressed in group of patients with <100 mg of LDL-C level at follow up. But so far, there are no systematic reviews of the effects of LDL-C levels on CAP, and the targets of LDL-C level that could result in the regression of the plaques have not been settled.

In this study, we conducted meta-analyses to summarize findings from the current trials on LDL-C lowering therapy retarding the progression of the CAP and to identify the targets of LDL-C resulting in the regression of the CAP for guiding the LDL-C lowering therapy. Effect of different statins on the progression of the CAP was also investigated.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

An electronic literature search was performed to identify all relevant studies published in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases in the English language from Jan. 1, 2000 to Jan. 1, 2014, using the terms “atherosclerosis” and “cholesterol blood level”. The references of the studies were also searched for relevant studies. Studies were included using the following criteria: 1) randomized controlled or prospective, blinded end-points trials in which patients with CHD were assigned to LDL-C lowering therapy or placebo, and its primary end point was CAP change detected by IVUS; 2) report of LDL-C levels at baseline and follow-up (in each arm) or the level of LDL-C which can be calculated from the data in the paper (as in the trial by Yokoyama M [15], in which the LDL-C concentrations in control arm were directly extracted from the figure); 3) data on the volume of CAP, detected in IVUS at baseline and follow-up (in each arm), and volume of CAP was calculated as vessel volume minus lumen volume; Exclusion criteria were: 1) only CAP area or volume index or percent atheroma volume were detected by IVUS; 2) the levels of LDL-C at baseline or follow-up were not provided; and 3) target plaques were unstable.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed all potentially eligible studies and collected data on patient and study characteristics (author, year, design, sample size, the measures of LDL-C lowering, LDL-C levels, follow-up duration, and plaque volume), and any disagreement was resolved by consensus. The primary end point of this study was progression or regression of CAP detected by IVUS. Quality assessments were evaluated with Jadad quality scale [19].

Data synthesis and analysis

Continuous variables (change of CAP volume from baseline to follow-up) were analyzed using standardized mean differences (SMD).

The trials may have control arm and multiple active treatment arms, changes of plaque volume in every arms were used for pooled analysis. According to the levels and the reducing percentage of LDL-C at follow-up, the arms were grouped to following groups: ≤70, >70 ≤ 100HP (>70 ≤ 100 mg and reducing percentage ≥30%), >70 ≤ 100MP (>70 ≤ 100 mg and reducing percentage ≥0 < 30%), >70 ≤ 100LP (>70 ≤ 100 mg and reducing percentage <0%), >100 mg/dL; and <0, ≥0 < 30, ≥30 < 40, ≥40 < 50, ≥50% respectively, to investigate the effect of different levels of LDL-C at follow up on CAPs. According to different statins, the arms were grouped to following groups: rosuvastatin, atorvastatin , pitavastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin and pravastatin group, to investigate the effect of different statins on CAPs. The volume of CAP at follow up was compared with that at baseline to evaluate effect of LDL-C levels on regression of CAP.

Heterogeneity across trials (arms) was assessed via a standard χ2 test with significance being set at p < 0.10 and also assessed by means of I 2 statistic with significance being set at I 2 > 50%. Pooled analyses were calculated using fixed-effect models, whereas random-effect models were applied in case of significant heterogeneity across studies (arms). Sensitivity analyses (exclusion of one study at one time) were performed to determine the stability of the overall effects of LDL-C levels. Additionally, publication bias was assessed using the Egger regression asymmetry test. Mean LDL-C level and follow up duration of groups were calculated by descriptive statistics. A two-sided p values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) and Review Manager V5.2 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012).

Results

Eligible studies

The flow of selecting studies for the meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. Briefly, of the initial 647 articles, one hundred and twenty of abstracts were reviewed, resulting in exclusion of 100 articles, and 20 articles were reviewed in full text, resulting in exclusion of 10 trials and inclusion of 18 additional trials. Twenty two RCTs [12–16, 20–31], [32–36] and six blinded end-points trial [37–42] were carefully evaluated. Five trials were excluded because of specific the index of plaque (volume index in TRUTH [24], trial by Kovarnik T [31], by Hattori K [42], and by Petronio AS [32]; area in LACMART [38]); GAIN [20] excluded because of no data of plaque volume at follow up; trial by Zhang X [25] excluded because of no data of LDL-C; trial by Hong YJ [30] excluded because of wrong data at follow up. Sixteen RCT (ESTABLISH [14], REVERSAL [13], A-PLUS [21], ACTIVATE [22], ILLUSTRATE [23], JAPAN-ACS [12], REACH [26], SATURN [28], ARTMAP [29], ERASE [34], STRADIVARIUS [35], PERISCOPE [36], and trials by Yokoyama M [15], by Kawasaki M [16], by Hong MK [27], and Tani S [33]) and four blinded end-points trial (ASTEROID [37], COSMOS [40], trial by Jensen LO [39] and trial by Nasu K [41]) were finally analyzed.

The characteristics of the included trials were shown in Table 1. Among the 20 trials, there were 15 trials assessing statins (statin vs. usual care in 6 trials [14–16, 26, 33, 41]; intensive statin vs. moderate statin treatment in 5 trials [12, 13, 27–29]; follow up vs baseline in 3 trial [37, 39, 40], before acute coronary syndrome (ACS) vs after ACS in one trial [34]), 2 trials assessing enzyme acyl–coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) inhibition (vs. placebo, both on the basis of mean LDL-C < 102 after background lipid-lowering therapy with statins in 62-79% of patients) [21, 22], one trial assessing cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor torcetrapib (vs. statins on the basis of LDL-C ≤ 100 by statins) [23], one trial assessing a decreasing obesity drug: rimonabant (vs. placebo, on the basis of statins therapy) [35], and one trial assessing glucose-lowering agents (pioglitazone vs glimepiride on the basis of statins therapy) [36]. In three trials [12, 14, 34] with acute coronary syndrome, all target plaques were selected in non-culprit vessels. Overall, 5910 patients with CHD underwent serial IVUS examination for evaluating regression of CAP. Follow-up periods ranged from 2 to 24 months. The levels of LDL-C of each arm at baseline and follow-up were shown in Table 2.

Risk of bias of included studies, evaluated through Cochrane’s methods, showed an overall acceptable quality of selected trials (Figures 2 and 3).

The effect of the levels of LDL-C at follow-up on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque

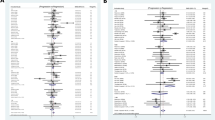

LDL-C lowering in group ≤70 and >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL could lead to regression of CAP, but LDL-C lowering in group >70 ≤ 100MP, >70 ≤ 100LP and >100 mg/dL could not (Figure 4, Table 3).

Meta-analysis of the effects of reduction levels of LDL-C at follow up on the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Abbreviations: Ato, Atorvastatin; Ros, Rosuvastatin; Pra, Pravastatin; Pit, Pitavastatin; Sim, Simvastatin; Flu, Fluvastatin; Con, Control; Pac, Pactimibe; Tor, Torcetrapib, Ava 50, 250, 750, Avasimibe 50, 250, 750 mg; Bef, before ACS; Aft, after ACS; Gli, Glimepiride; Pio, Pioglitazone; Rim, Rimonabant.

In group ≤70 mg/dL (including seven arms) with mean 18.6 months of follow up and group >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL (including eleven arms) with mean 17.4 months of follow up, the volumes of CAP (125.9, 123.8 mm3 respectively) at follow up were significantly decreased, compared with the volumes (177.1, 129.7 mm3 respectively) at baseline [SMD −0.156 mm3, 95% CI (confidence interval) -0.235 ~ −0.078, p = 0.000; SMD −0.123 mm3, 95% CI −0.199 ~ −0.048, p = 0.001; respectively]. There was no significant heterogeneity among arms (χ2 for heterogeneity = 0.57, p =0.997, I 2 = 0% for group ≤70 mg/dL; χ2 for heterogeneity = 6.83, p =0.741, I 2 = 0% for group >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL).

Sensitivity analyses suggested that LDL-C lowering in group ≤70 and >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL could lead to regression of CAP with reduction of the CAP volume ranged from −0.146 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.238 ~ −0.054) when the arm of 2006 ASTEROID Ros was omitted to −0.167 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.270 ~ −0.064) when the arm of 2011 SATURN Ros was omitted; and from −0.103 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.182 ~ −0.024) when the arm of 2009 JAPAN-ACS Ato was omitted to −0.151 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.235 ~ −0.067) when the arm of 2004 REVERSAL Ato was omitted. No publication bias was found, the values of p by Egger’s test for group ≤70 and >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL were 0.835, 0.501 respectively.

In group >100 mg/dL (including eleven arms) with mean 14.6 months of follow up, the volume of CAP at follow up was not significantly increased, compared with the volumes at baseline (SMD 0.013 mm3, 95% CI −0.092 ~ 0.118, p = 0.809). There was no significant heterogeneity among arms (χ2 for heterogeneity = 2.49, p =0.991, I 2 = 0%).

Sensitivity analyses suggested that LDL-C lowering to >100 mg/dL at follow-up could still not lead to regression of CAP with reduction of the plaque volume ranged from −0.005 mm3 (95% CI −0.136 ~ 0.126) when the arm of 2004 REVERSAL Pro was omitted to 0.034 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI −0.075 ~ 0.143) when 2005 Tani S Pra was omitted. No publication bias was observed from the values of p (0.566) by Egger’s test.

Mean levels of LDL-C at baseline and follow up and mean reducing percentage of LDL-C in group ≤70, >70 ≤ 100HP, >70 ≤ 100MP, >70 ≤ 100LP and >100 mg/dL were showed in Table 4.

The effect of the LDL-C reducing percentage at follow-up on regression of CAP

LDL-C lowering in group ≥30 < 40, ≥40 < 50, ≥50% could lead to regression of CAP, but LDL-C lowering in group <0 and ≥0 < 30% could not (Figure 5, Table 3).

Meta-analysis of the effects of reduction percentages of LDL-C at follow up on the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Abbreviations: Ato, Atorvastatin; Ros, Rosuvastatin; Pra, Pravastatin; Pit, Pitavastatin; Sim, Simvastatin; Flu, Fluvastatin; Con, Control; Pac, Pactimibe; Tor, Torcetrapib, Ava 50, 250, 750, Avasimibe 50, 250, 750 mg; Bef, before ACS; Aft, after ACS; Gli, Glimepiride; Pio, Pioglitazone; Rim, Rimonabant.

In group ≥30 < 40% (including ten arms) with mean 10.3 months of follow up, and group ≥40 < 50% (including eight arms) with mean 19.4 months of follow up, the volumes of CAP (94.3, 150.7 mm3 respectively) at follow up were significantly decreased, compared with the volumes (102.9, 157.8 mm3 respectively) at baseline (SMD −0.199 mm3, 95% CI −0.314 ~ −0.085, p = 0.001; SMD −0.108 mm3, 95% CI −0.176 ~ −0.040, p = 0.002; respectively). There was no significant heterogeneity among arms (χ2 for heterogeneity = 3.10, P = 0.960, I 2 = 0%; χ2 for heterogeneity = 2.50, p =0.927, I 2 = 0%; for group ≥30 < 40, and group ≥40 < 50 respectively).

Sensitivity analyses showed that LDL-C lowering in group ≥30 < 40% and group ≥40 < 50 could still lead to regression of CAP with reduction of the plaque volume ranged from −0.166 mm3 (95% CI −0.295 ~ −0.038) when the arm of 2009 JAPAN-ACS Ato was omitted to −0.214 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI −0.342 ~ −0.085) when 2009 COSMOS Ros was omitted; from −0.093 mm3 (95% CI −0.174 ~ −0.011) when the arm of 2011 SATURN Ros was omitted to −0.126 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI −0.200 ~ −0.053) when 2004 REVERSAL Ato was omitted respectively. Publication bias analysis suggested the values of p by Egger’s test were 0.024, 0.605 for group ≥30 < 40, and group ≥40 < 50 respectively.

In group <0 with mean 19.6 months of follow up and group ≥0 < 30% with mean 18.3 months of follow up, the volume of CAP at follow up was not significantly decreased, compared with the volumes at baseline (SMD −0.034 mm3, 95% CI −0.111 ~ 0.044, p = 0.396; SMD −0.032 mm3, 95% CI −0.093 ~ 0.030, p = 0.315 respectively). There was no significant heterogeneity among arms (χ2 for heterogeneity = 1.55, p =0.981, I 2 = 0% for group <0%; χ2 for heterogeneity = 4.59, p =0.970, I 2 = 0% for group ≥0 < 30%).

Sensitivity analyses showed that LDL-C lowering in group ≥0 < 30% could not still significantly decrease the volume of CAP with reduction of the CAP volume ranged from −0.010 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.080 ~ 0.061) when the arm of 2007 ILLUSTRATE Ato + Tor was omitted to −0.042 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.108 ~ 0.024) when the arm of 2004 REVERSAL Pro was omitted. No publication bias was found, the values of p by Egger’s test for group ≥0 < 30% were 0.537.

Mean levels of LDL-C at baseline and follow up, mean reducing percentage of LDL-C in group <0, ≥0 < 30, ≥30 < 40, ≥40 < 50 and ≥50%, were showed in Table 4.

The effect of lowering LDL-C by statins on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque

LDL-C lowering by rosuvastatin, atorvastatin and pitavastatin in group ≤70 and >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL could lead to regression of CAP, but LDL-C lowering by simvastatin, fluvastatin and pravastatin could not (Figure 6, Table 5).

Meta-analysis of the effects of LDL-C lowering by different statins on the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Abbreviations: Ato, Atorvastatin; Ros, Rosuvastatin; Pra, Pravastatin; Pit, Pitavastatin; Sim, Simvastatin; Flu, Fluvastatin; Con, Control; Pac, Pactimibe; Tor, Torcetrapib, Ava 50, 250, 750, Avasimibe 50, 250, 750 mg; Bef, before ACS; Aft, after ACS; Gli, Glimepiride; Pio, Pioglitazone; Rim, Rimonabant.

LDL-C lowering by rosuvastatin (mean 33.3 mg daily for mean 20 months), atorvastatin (mean 60.3 mg daily for mean 17 months) and pitavastatin (4 mg daily for 8 ~ 12 months) in group ≤70 and >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL could significantly decrease the volumes of CAP at follow up, compared with the volumes at baseline (SMD −0.162 mm3, 95% CI: −0.234 ~ −0.081, p = 0.000; SMD −0.101, 95% CI: −0.184 ~ −0.019, p = 0.016; SMD −0.304 mm3, 95% CI: −0.553 ~ −0.055, p = 0.017; respectively). There was no significant heterogeneity among arms (χ2 for heterogeneity = 0.37, p =0.985, I 2 = 0% for rosuvastatin; χ2 for heterogeneity = 4.44, p =0.728, I 2 = 0% for atorvastatin.

Sensitivity analyses suggested that lowering LDL-C by rosuvastatin could lead to regression of CAP with reduction of the plaque volume ranged from −0.153 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.249 ~ −0.056) when the arm of 2006 ASTEROID Ros was omitted to −0.178 mm3 (SMD, 95% CI: −0.287 ~ −0.069) when the arm of 2011 SATURN Ros was omitted. Lowering LDL-C by atorvastatin could, but not significantly, lead to regression of CAP when the arm of 2009 JAPAN-ACS Ato was omitted (SMD: −0.075 mm3, 95% CI: −0.162 ~ 0.012). No publication bias was found, the values of p by Egger’s test for rosuvastatin and atorvastatin group were 0.770, 0.582 respectively (Table 5).

Intensity of lowering LDL-C by different statins was shown in Table 6. Rosuvastatin and atorvastatin could reduce LDL-C by more than 40%.

Discussion

Feature of this meta-analysis

This meta-analysis broke though the limit of single trial, and pooled arms together according to the levels of LDL-C at follow up in the arms, regardless of the measures of lowering LDL-C: treating arm (statins, ACAT inhibitor, CETP inhibitor, decreasing obesity drug, and glucose-lowering agents) and control arms (dietary restriction, moderate LDL-C lowering by statin); intensive and moderate LDL-C lowering. The volumes of CAP at follow up were compared with those at baseline in the same arms to evaluate the regression of the CAPs, this meta-analysis really reflected the change of the plaques volume with the change of LDL-C levels.

Our meta-analysis results indicated that intensive lowering LDL-C in group ≤70, >70 ≤ 100HP mg/dL (mean follow up LDL-C, mean duration of follow up: 60.6 mg/dL, 18.6 months; 77.8 mg/ dL, 17.4 months respectively), ≥30 < 40, ≥40 < 50 and ≥50% (mean LDL-C reducing, mean duration of follow up: 36.1%, 10.3 months; 45.4%, 19.4 months; 53.2%, 24 months respectively) could lead to the regression of CAP; that moderate lowering LDL-C in group >70 ≤ 100MP mg/dL (mean LDL-C reducing by 9.1%, mean 19.8 months of follow up), >100 (mean follow up LDL-C 110.0 and mean 14.6 months of follow up) mg/dL and ≥0 < 30% (mean LDL-C reducing by 10.6%, mean 18.3 months of follow up) could not lead to the regression; and that intensive lowering LDL-C, by mean 48% with rosuvastatin, and by mean 42% with atorvastatin, could regress CAP. The sensitivity analysis confirmed the effect of the LDL-C change on the volume of the plaque.

The importance of intensive lowing LDL-C on regression of CAP and LDL-C target of this meta-analysis

In the trials that evaluated the effects of LDL-C lowering on atheroma progression by IVUS, the effects varied with level of LDL-C at follow up. In group ≤70 mg, ≥30 < 40% and ≥40 < 50%, the LDL-C at baseline in most trials (including ESTABLISH [14], REVERSAL [13], JAPAN-ACS [12], ASTEROID [37], COSMOS [40], trial by Kawasaki M [16] and by Nasu K [41]) were >120 mg. In ASTEROID [37], COSMOS [40], JAPAN-ACS [12] trial and fluvastatin arm of the trial by Nasu K [41] with respective the mean LDL-C level 60.8 mg, 82.9 mg, 81-84 mg and 98 mg (53.2%, 38.6%, 36% and 32.3% reduction of level of LDL-C) at follow up, it was showed that CAP could be regressed with intensive statin therapy. In ESTABLISH [14] and REVERSAL [13], the mean reducing percent of LDL-C at follow up in the statin treatment arms were 44% and 46% respectively, the volumes of CAPs at follow up were not significantly decreased, compared with those in baseline. In the trails by Yokoyama M [15] and Kawasaki M [16], mean reducing percentage of LDL-C at follow up was 35% for atorvastatin arm of the trial by Yokoyama M [15], 32% for pravastatin arm of the trial by Kawasaki M [16] and 39% for atorvastatin arm of the trial by Kawasaki M [16], the volume of CAPs at follow up were also not significantly decreased, compared with that at baseline. Pooled these arms with follow up LDL-C ≤70 mg or reducing >30% together, these meta-analysis showed that the CAPs could be regressed in group ≤70 mg, ≥30 < 40% and ≥40 < 50%. Because of publication bias in group ≥30 < 40% (Table 3), the level of LDL-C in this group could not be recommended for regressing CAP. Based on the mean level and reducing percentage of LDL-C in group ≤70 mg and ≥40 < 50% (60.6 ± 3.5 mg, 48.8 ± 3.3%; 66.8 ± 8.0 mg, 45.4 ± 2.8%, in Table 4), the meta-analysis in group ≤70 mg and ≥40 < 50% suggested that for regressing CAP, LDL-C should be reduced by >45% or to a target level ≤ 66 mg/dL.

In trials with 18–24 months of non-statin (ACAT inhibitor, decreasing obesity drugs and glucose-lowering agents) treatment, although the levels of LDL-C at follow up in some arms (ACTIVATE [22], STRADIVARIUS [35], PERISCOPE [36], and A-PLUS [21] with daily 50 mg of avasimibe) were >70 ≤ 100 mg/dL, the LDL-C lowering percentage at follow up in the arms were below 30% because the levels of LDL-C at baseline were <95 mg/dL. In ILLUSTRATE trial [23], after treatment with atorvastatin to reduce levels of LDL-C to less than 100 mg/dL, patients were randomly assigned to receive either atorvastatin monotherapy or atorvastatin plus 60 mg of torcetrapib daily. After 24 months, the reduction of LDL-C in both arms was <24% and the progression of CAP was not halted. In trial [34, 35] with statins treatment and baseline LDL-C < 110 mg, if the LDL-C lowering percentage at follow up were <24%, the CAP was also not regressed. The meta analysis with six arms in group >70 ≤ 100LP mg/dL and five arms in group >70 ≤ 100MP mg/dL did not show that only >70 ≤ 100 mg/dL of LDL-C level but <30% reduction at follow up could lead to regression of CAP, which further confirmed the importance of intensively lowering LDL-C in regression of CAP. Though LDL-C at follow up in some trials [13, 15, 16, 26, 27, 39] of LDL-C lowering by statins was >70 ≤ 100 mg/dL and reducing >30%, the CAP in the trials was also not regressed. Included eleven arms with baseline LDL-C >130.0 mg/dL, follow up LDL-C >70 ≤ 100 mg/dL and LDL-C reducing >30% (in group >70 ≤ 100HP mg), this meta-analysis suggested that LDL-C reducing >40% or to target 77.8 mg could regress CAP (Table 4). The meta-analysis in group >70 ≤ 100HP, >70 ≤ 100MP and >70 ≤ 100LP mg/dL indicated that LDL-C reducing percentage, not lowering absolute value of LDL-C at follow up, was important for regressing CAP.

Although rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, pitavastatin, simvastatin, and fluvastatin in some trials could reduce LDL-C level to ≤100 mg or by 30%, the meta-analysis indicated that rosuvastatin, atorvastatin and pitavastatin (mean lowering LDL-C by 48.4%, 42.3% and 36.2% respectively) could regress the CAPs, and simvastatin with mean lowering LDL-C by 39.9% could not. The role of pitavastatin in regressing CAPs remains to be verified because the role was from only one RCT with 125 cases [12]. Pravastatin with mean lowering LDL-C by 24.6% could not regress the CAPs either. Fluvastatin with mean lowering LDL-C by 32.3% in the blinded endpoint trial with 40 patients can regress the CAP [41], but meta-analysis indicated that fluvastatin could not regress the CAP. The reason that pravastatin and fluvastatin in this meta–analysis can not regress the CAPs might be attributed to their low-intensity of lowering LDL-C and low dosage which can not reduce LDL-C by >40%.

Taken all the results of meta-analysis together, it was recommended that LDL-C level should be reduced by >40% or to a target level < 78 mg/dL for regressing CAP.

The difference of LDL-C target level between this meta-analysis and current guidelines

The patients included in this meta-analysis were coronary heart disease. According to 2004 the guideline of the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program [43] and 2011 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias [1], this group of patients belongs to very high risk category, and the recommended targets of LDL-C should be less than 70 mg/dL or 30-40% reduction from baseline in ATP III, and less than 70 mg/dL or a ≥50% reduction in 2011 ESC/EAS Guidelines. The target levels for subjects at very high risk in the both guidelines are extrapolated from several clinical trials [43], mainly from the meta-analysis by Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaborators [44], which indicated that absolute benefit of LDL-C lowering related chiefly to the absolute reduction of LDL-C, and the risk reductions are proportional to the absolute LDL-C reductions, but the meta-analysis did not provide target level of LDL-C for the benefit in terms of cardiovascular disease reduction [44]. According to 2013 ACC/AHA blood cholesterol guideline [45], this group of patients should be treated with high-intensity statin (atorvastatin 40–80 mg daily or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg daily), which was the intensity of statin suggested in this meta-analysis (Table 6).

The results of our meta-analysis imply that the patients with CHD should be intensively treated with statins (rosuvastatin 33 mg or atorvastatin 60 mg daily) to reduce the level of LDL-C by >40% or to a target level <78 mg/dL for regressing CAP, which have a little different to the guidelines. These different targets level of LDL-C might be due to different observational index: cardiovascular events for both guidelines, CAP volume for this meta-analysis. Moreover, our target is directly from meta-analysis, the target of 2011 ESC/EAS Guidelines is from extrapolation of meta-analysis, not a direct data. Our meta-analysis revealed the relation between the regression of coronary artery disease and LDL-C level from the view of pathological anatomy. Published meta-analysis [17, 18] about CAP by IVUS did not review the relationship between LDL-C level and CAP.

Study limitation

The results of this analysis were obtained by pooling data from twenty clinical trials. As with any meta-analysis, this study has some limitations. Firstly, though no publication bias was observed by Egger’s test there may be a potential of publication bias because only published data were included. Secondly, the methodology used for measurement of coronary atheroma might not be the same in the studies. The plaques volume may be calculated from slices with 1 mm apart for a length of 10 mm vessel in some trials [13, 15, 22, 23, 27–29, 37], or 0.1-0.3 mm-apart for a length of 10–50 mm vessel in other trials [12, 21, 33, 39, 40], which might affect accuracy of plaque measurement. There were some differences in selecting plaque: some trials assessed the plaque in non-culprit vessel, while others assessed non-culprit plaque in a culprit vessel [12, 14, 34], which assured the plaque was stable. Our study focus on target plaque change, i.e. plaque regression or progression, those differences in measurements and plaque selection did not affect the change of the target plaque with LDL-C levels. So, it has little effect on homogeneous of studies, and this detection bias was very much limited from values of P in χ2 test and I 2 in each group. Thirdly, follow up duration might have some effects of the changes of CAP. Fourthly, other cardiovascular risk factors but LDL-C levels, for example, demographic characteristics such as age, gender and ethnicity, might also affect the effect of LDL-C on CAP, and the effects of these factors on CAP remain to be investigated in future.

Implication for practice

This meta-analysis investigated the effect of reduction of LDL-C only on the regression of the plaque, not on reduction of cardiovascular events. In fact, all the included trial have no the data about death because only the alive have IVUS data at follow up. But in four-year of the OLIVUS-Ex [46], it was found that patients with annual atheroma progression had more adverse cardio- and cerebrovascular events than the rest of the population. A meta-analysis [47] included 7864 CAD patients showed that rates of plaque volume regression were significantly associated with the incidence of MI or revascularization, and it was concluded that regression of atherosclerotic coronary plaque volume in stable CAD patients may represent a surrogate for myocardial infarction and repeat revascularization. Plaque in CAD, as blood pressure level in hypertension, is not major adverse cardiac events, but does be an important surrogate. Therefore, the conclusion of this meta-analysis not only applies to guide LDL-C lowering therapy for regressing CAP, may also apply to guide LDL-C lowering therapy for reducing major adverse cardio- and cerebrovascular events. Furthermore, high level of LDL-C plays a crucial role in the formation of atherosclerotic plaque, but LDL-C level is not unique risk factor for atherosclerotic plaque. Hypertension is another important risk factor for the formation of plaque [48, 49]. Smoking cessation, administrating β-blockers, anti-hypertension therapy might play some role in slowing progression of CAP [48, 50–52]. The trend of CAP regression in group <0% might attribute to these non-LDL-C reducing factors.

Conclusions

Atherosclerotic plaque extension and disruption are basic mechanism of atherosclerotic cardio- and cerebrovascular disease. Stabling and regressing atherosclerotic plaque play an important role in preventing cardio- and cerebrovascular disease. Pooled the twenty trials with CAP detected by gold standard: IVUS, this systemic review demonstrated that intensive lowering LDL-C (rosuvastatin mean 33 mg daily and atorvastatin mean 60 mg daily) with >17 months of duration could lead to the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque, LDL-C level should be reduced by >40% or to a target level < 78 mg/dL for regressing CAP.

Abbreviations

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- CAP:

-

Coronary atherosclerotic plaque

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- CAG:

-

Coronary angiography

- IVUS:

-

Intravascular ultrasound

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean differences

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- ACAT:

-

Acyl–coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase

- CETP:

-

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ATP III:

-

Adult Treatment Panel III

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease.

References

Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, Agewall S, Alegria E, Chapman MJ, Durrington P, Erdine S, Halcox J, Hobbs R, Kjekshus J, Filardi PP, Riccardi G, Storey RF, Wood D: ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011, 32: 1769-1818.

Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V: Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995, 92: 657-671. 10.1161/01.CIR.92.3.657.

The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group: Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339: 1349-1357.

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group: Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994, 344: 1383-1389.

Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, Schaefer SM, Lin JT, Kaplan C, Zhao XQ, Bisson BD, Fitzpatrick VF, Dodge HT: Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med. 1990, 323: 1289-1298. 10.1056/NEJM199011083231901.

Blankenhorn DH, Azen SP, Kramsch DM, Mack WJ, Cashin-Hemphill L, Hodis HN, DeBoer LW, Mahrer PR, Masteller MJ, Vailas LI, Alaupovic P, Hirsch LJ: Coronary angiographic changes with lovastatin therapy. The Monitored Atherosclerosis Regression Study (MARS). Ann Intern Med. 1993, 119: 969-976. 10.7326/0003-4819-119-10-199311150-00002.

Thomas AC, Davies MJ, Dilly S, Dilly N, Franc F: Potential errors in the estimation of coronary arterial stenosis from clinical arteriography with reference to the shape of the coronary arterial lumen. Br Heart J. 1986, 55: 129-139. 10.1136/hrt.55.2.129.

Hausmann D, Johnson JA, Sudhir K, Mullen WL, Friedrich G, Fitzgerald PJ, Chou TM, Ports TA, Kane JP, Malloy MJ, Yock PG: Angiographically silent atherosclerosis detected by intravascular ultrasound in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and familial combined hyperlipidemia: correlation with high density lipoproteins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996, 27: 1562-1570. 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00048-4.

Mintz GS, Painter JA, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Popma JJ, Chuang YC, Bucher TA, Sokolowicz LE, Leon MB: Atherosclerosis in angiographically “normal” coronary artery reference segments: an intravascular ultrasound study with clinical correlations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995, 25: 1479-1485. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00088-L.

Nissen SE, Yock P: Intravascular ultrasound: novel pathophysiological insights and current clinical applications. Circulation. 2001, 103: 604-616. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.4.604.

Takagi T, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, Hozumi T, Morioka S, Yoshikawa J: Intravascular ultrasound analysis of reduction in progression of coronary narrowing by treatment with pravastatin. Am J Cardiol. 1997, 79: 1673-1676. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00221-X.

Hiro T, Kimura T, Morimoto T, Miyauchi K, Nakagawa Y, Yamagishi M, Ozaki Y, Kimura K, Saito S, Yamaguchi T, Daida H, Matsuzaki M: Effect of intensive statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a multicenter randomized trial evaluated by volumetric intravascular ultrasound using pitavastatin versus atorvastatin (JAPAN-ACS [Japan assessment of pitavastatin and atorvastatin in acute coronary syndrome] study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54: 293-302. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.033.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, Crowe T, Howard G, Cooper CJ, Brodie B, Grines CL, DeMaria AN: Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004, 291: 1071-1080. 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071.

Okazaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyauchi K, Shimada K, Kurata T, Sato H, Daida H: Early statin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: demonstration of the beneficial effect on atherosclerotic lesions by serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis during half a year after coronary event: the ESTABLISH Study. Circulation. 2004, 110: 1061-1068. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140261.58966.A4.

Yokoyama M, Komiyama N, Courtney BK, Nakayama T, Namikawa S, Kuriyama N, Koizumi T, Nameki M, Fitzgerald PJ, Komuro I: Plasma low-density lipoprotein reduction and structural effects on coronary atherosclerotic plaques by atorvastatin as clinically assessed with intravascular ultrasound radio-frequency signal analysis: a randomized prospective study. Am Heart J. 2005, 150: 287-

Kawasaki M, Sano K, Okubo M, Yokoyama H, Ito Y, Murata I, Tsuchiya K, Minatoguchi S, Zhou X, Fujita H, Fujiwara H: Volumetric quantitative analysis of tissue characteristics of coronary plaques after statin therapy using three-dimensional integrated backscatter intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45: 1946-1953. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.081.

Bedi U, Singh M, Singh P, Molnar J, Khosla S, Arora R: Effects of statins on progression of coronary artery disease as measured by intravascular ultrasound. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011, 13: 492-496. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00428.x.

Tian J, Gu X, Sun Y, Ban X, Xiao Y, Hu S, Yu B: Effect of statin therapy on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012, 12: 70-10.1186/1471-2261-12-70.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Schartl M, Bocksch W, Koschyk DH, Voelker W, Karsch KR, Kreuzer J, Hausmann D, Beckmann S, Gross M: Use of intravascular ultrasound to compare effects of different strategies of lipid-lowering therapy on plaque volume and composition in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001, 104: 387-392. 10.1161/hc2901.093188.

Tardif JC, Gregoire J, L’Allier PL, Anderson TJ, Bertrand O, Reeves F, Title LM, Alfonso F, Schampaert E, Hassan A, McLain R, Pressler ML, Ibrahim R, Lesperance J, Blue J, Heinonen T, Rodes-Cabau J: Effects of the acyl coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase inhibitor avasimibe on human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2004, 110: 3372-3377. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147777.12010.EF.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Brewer HB, Sipahi I, Nicholls SJ, Ganz P, Schoenhagen P, Waters DD, Pepine CJ, Crowe TD, Davidson MH, Deanfield JE, Wisniewski LM, Hanyok JJ, Kassalow LM: Effect of ACAT inhibition on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354: 1253-1263. 10.1056/NEJMoa054699.

Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, Revkin JH, Shear CL, Duggan WT, Ruzyllo W, Bachinsky WB, Lasala GP, Tuzcu EM: Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 1304-1316. 10.1056/NEJMoa070635.

Nozue T, Yamamoto S, Tohyama S, Umezawa S, Kunishima T, Sato A, Miyake S, Takeyama Y, Morino Y, Yamauchi T, Muramatsu T, Hibi K, Sozu T, Terashima M, Michishita I: Statin treatment for coronary artery plaque composition based on intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. Am Heart J. 2012, 163: 191-199. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.11.004. e1

Zhang X, Wang H, Liu S, Gong P, Lin J, Lu J, Qiu J, Lu X: Intensive-dose atorvastatin regimen halts progression of atherosclerotic plaques in new-onset unstable angina with borderline vulnerable plaque lesions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2013, 18: 119-125. 10.1177/1074248412465792.

Yamada T, Azuma A, Sasaki S, Sawada T, Matsubara H: Randomized evaluation of atorvastatin in patients with coronary heart disease: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circ J. 2007, 71: 1845-1850. 10.1253/circj.71.1845.

Hong MK, Park DW, Lee CW, Lee SW, Kim YH, Kang DH, Song JK, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ: Effects of statin treatments on coronary plaques assessed by volumetric virtual histology intravascular ultrasound analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009, 2: 679-688. 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.03.015.

Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Chapman MJ, Erbel RM, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Uno K, Borgman M, Wolski K, Nissen SE: Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365: 2078-2087. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110874.

Lee CW, Kang SJ, Ahn JM, Song HG, Lee JY, Kim WJ, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim YH, Park SW, Park SJ: Comparison of effects of atorvastatin (20 mg) versus rosuvastatin (10 mg) therapy on mild coronary atherosclerotic plaques (from the ARTMAP trial). Am J Cardiol. 2012, 109: 1700-1704. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.01.399.

Hong YJ, Jeong MH, Hachinohe D, Ahmed K, Choi YH, Cho SH, Hwang SH, Ko JS, Lee MG, Park KH, Sim DS, Yoon NS, Yoon HJ, Kim KH, Park HW, Kim JH, Ahn Y, Cho JG, Park JC, Kang JC: Comparison of effects of rosuvastatin and atorvastatin on plaque regression in Korean patients with untreated intermediate coronary stenosis. Circ J. 2011, 75: 398-406. 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0658.

Kovarnik T, Mintz GS, Skalicka H, Kral A, Horak J, Skulec R, Uhrova J, Martasek P, Downe RW, Wahle A, Sonka M, Mrazek V, Aschermann M, Linhart A: Virtual histology evaluation of atherosclerosis regression during atorvastatin and ezetimibe administration: HEAVEN study. Circ J. 2012, 76: 176-183. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0730.

Petronio AS, Amoroso G, Limbruno U, Papini B, De Carlo M, Micheli A, Ciabatti N, Mariani M: Simvastatin does not inhibit intimal hyperplasia and restenosis but promotes plaque regression in normocholesterolemic patients undergoing coronary stenting: a randomized study with intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 2005, 149: 520-526. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.10.032.

Tani S, Watanabe I, Anazawa T, Kawamata H, Tachibana E, Furukawa K, Sato Y, Nagao K, Kanmatsuse K, Kushiro T: Effect of pravastatin on malondialdehyde-modified low-density lipoprotein levels and coronary plaque regression as determined by three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol. 2005, 96: 1089-1094. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.069.

Rodes-Cabau J, Tardif JC, Cossette M, Bertrand OF, Ibrahim R, Larose E, Gregoire J, L’allier PL, Guertin MC: Acute effects of statin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis following an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009, 104: 750-757. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.009.

Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Wolski K, Rodes-Cabau J, Cannon CP, Deanfield JE, Despres JP, Kastelein JJ, Steinhubl SR, Kapadia S, Yasin M, Ruzyllo W, Gaudin C, Job B, Hu B, Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM, Tuzcu EM: Effect of rimonabant on progression of atherosclerosis in patients with abdominal obesity and coronary artery disease: the STRADIVARIUS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 299: 1547-1560. 10.1001/jama.299.13.1547.

Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Wolski K, Nesto R, Kupfer S, Perez A, Jure H, De Larochelliere R, Staniloae CS, Mavromatis K, Saw J, Hu B, Lincoff AM, Tuzcu EM: Comparison of pioglitazone vs glimepiride on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: the PERISCOPE randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 299: 1561-1573. 10.1001/jama.299.13.1561.

Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, Schoenhagen P, Crowe T, Cain V, Wolski K, Goormastic M, Tuzcu EM: Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006, 295: 1556-1565. 10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002.

Matsuzaki M, Hiramori K, Imaizumi T, Kitabatake A, Hishida H, Nomura M, Fujii T, Sakuma I, Fukami K, Honda T, Ogawa H, Yamagishi M: Intravascular ultrasound evaluation of coronary plaque regression by low density lipoprotein-apheresis in familial hypercholesterolemia: the Low Density Lipoprotein-Apheresis Coronary Morphology and Reserve Trial (LACMART). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40: 220-227. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01955-1.

Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Pedersen KE, Stender S, Haghfelt T: Regression of coronary atherosclerosis by simvastatin: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004, 110: 265-270. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135215.75876.41.

Takayama T, Hiro T, Yamagishi M, Daida H, Hirayama A, Saito S, Yamaguchi T, Matsuzaki M: Effect of rosuvastatin on coronary atheroma in stable coronary artery disease: multicenter coronary atherosclerosis study measuring effects of rosuvastatin using intravascular ultrasound in Japanese subjects (COSMOS). Circ J. 2009, 73: 2110-2117. 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0358.

Nasu K, Tsuchikane E, Katoh O, Tanaka N, Kimura M, Ehara M, Kinoshita Y, Matsubara T, Matsuo H, Asakura K, Asakura Y, Terashima M, Takayama T, Honye J, Hirayama A, Saito S, Suzuki T: Effect of fluvastatin on progression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque evaluated by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009, 2: 689-696.

Hattori K, Ozaki Y, Ismail TF, Okumura M, Naruse H, Kan S, Ishikawa M, Kawai T, Ohta M, Kawai H, Hashimoto T, Takagi Y, Ishii J, Serruys PW, Narula J: Impact of statin therapy on plaque characteristics as assessed by serial OCT, grayscale and integrated backscatter-IVUS. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012, 5: 169-177. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.11.012.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Stone NJ: Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004, 110: 227-239. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E.

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R: Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1267-1278.

Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Watson K, Wilson PW: 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013, 00: 000-

Hirohata A, Yamamoto K, Miyoshi T, Hatanaka K, Hirohata S, Yamawaki H, Komatsubara I, Hirose E, Kobayashi Y, Ohkawa K, Ohara M, Takafuji H, Sano F, Toyama Y, Kusachi S, Ohe T, Ito H: Four-year clinical outcomes of the OLIVUS-Ex (impact of Olmesartan on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: evaluation by intravascular ultrasound) extension trial. Atherosclerosis. 2012, 220: 134-138. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.10.013.

D’Ascenzo F, Agostoni P, Abbate A, Castagno D, Lipinski MJ, Vetrovec GW, Frati G, Presutti DG, Quadri G, Moretti C, Gaita F, Zoccai GB: Atherosclerotic coronary plaque regression and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Atherosclerosis. 2013, 226: 178-185. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.065.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Libby P, Thompson PD, Ghali M, Garza D, Berman L, Shi H, Buebendorf E, Topol EJ: Effect of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004, 292: 2217-2225. 10.1001/jama.292.18.2217.

Hirohata A, Yamamoto K, Miyoshi T, Hatanaka K, Hirohata S, Yamawaki H, Komatsubara I, Murakami M, Hirose E, Sato S, Ohkawa K, Ishizawa M, Yamaji H, Kawamura H, Kusachi S, Murakami T, Hina K, Ohe T: Impact of olmesartan on progression of coronary atherosclerosis a serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis from the OLIVUS (impact of OLmesarten on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: evaluation by intravascular ultrasound) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55: 976-982. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.062.

Redgrave JN, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM: Histological features of symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to age and smoking: the oxford plaque study. Stroke. 2010, 41: 2288-2294. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.587006.

Heidland UE, Strauer BE: Left ventricular muscle mass and elevated heart rate are associated with coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 2001, 104: 1477-1482. 10.1161/hc3801.096325.

Sipahi I, Tuzcu EM, Wolski KE, Nicholls SJ, Schoenhagen P, Hu B, Balog C, Shishehbor M, Magyar WA, Crowe TD, Kapadia S, Nissen SE: Beta-blockers and progression of coronary atherosclerosis: pooled analysis of 4 intravascular ultrasonography trials. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 147: 10-18. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00003.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/14/60/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. This study was not funded.

Authors’ contributions

GWQ, FQZ and LYF carried out data extraction, participated in the analysis and drafted the manuscript. LYX and LCY participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. HY, CYM and YB conceived the study, and participated in its statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Wen-Qian Gao, Quan-Zhou Feng, Yu-Feng Li contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, WQ., Feng, QZ., Li, YF. et al. Systematic study of the effects of lowering low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaques using intravascular ultrasound. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14, 60 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-60

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-60