Abstract

Background

The completion of genome sequencing in a number of Shewanella species, which are most renowned for their metal reduction capacity, offers a basis for comparative studies. Previous work in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 has indicated that some genes within a cluster (mtrBAC-omcA-mtrFED) were involved in iron reduction. To explore new features of iron reduction pathways, we experimentally analyzed Shewanella putrefaciens W3-18-1 since its gene cluster is considerably different from that of MR-1 in that the gene cluster encodes only four ORFs.

Results

Among the gene cluster, two genes (mtrC and undA) were shown to encode c-type cytochromes. The ΔmtrC deletion mutant revealed significant deficiencies in reducing metals of Fe2O3, α-FeO(OH), β-FeO(OH), ferric citrate, Mn(IV) and Co(III), but not organic compounds. In contrast, no deficiency of metal reduction was observed in the ΔundA deletion mutant. Nonetheless, undA deletion resulted in progressively slower iron reduction in the absence of mtrC and fitness loss under the iron-using condition, which was indicative of a functional role of UndA in iron reduction.

Conclusions

These results provide physiological and biochemical evidences that UndA and MtrC of Shewanella putrefaciens W3-18-1 are involved in iron reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A number of Gram-negative bacteria can grow anaerobically through dissimilatory reduction of metals such as insoluble Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxides [1]. Among these, the genus of Shewanella has been a focus of research for its versatile capabilities of dissimilatory metal reduction, which has potentials for bioremediation of toxic metals [2–4]. Because of its metabolic capabilities, Shewanella is widely distributed in diverse habitats of soil, fresh water, marine water and even hydrothermal vents, with a preference of residing in stratified environments [2, 5, 6].

The most studied strain of Shewanella is undoubtedly S. oneidensis MR-1. It has been well established that some genes of an mtrBAC-omcA-mtrFED gene cluster of MR-1, such as mtrBAC and omcA, is involved in Fe(III), Mn(IV) and U (VI) reduction. This cluster contains two genes (mtrC and omcA) encoding outer membrane c-type cytochromes that form a protein complex [7] and function as a terminal reductase towards solid-phase metal (hydr)oxides. To facilitate the interaction with the solid-phase metal(hydr)oxides, these two cytochromes are organized in that MtrC is spatially distributed on cell surface while OmcA is localized between cell surface and minerals, as shown by antibody-recognition force microscopy [8]. Consistently, the presence of both MtrC and OmcA was required for reduction of solid-phase metal(hydr)oxides [9–11]. In comparison, not much is known about the specific functions of mtrFED. Recently, it was reported that ΔmtrD showed no deficiency in reducing soluble and insoluble Fe(III), but soluble Fe(III) reduction of the mutant was progressively slower when mtrA was also absent, implicating a role in Fe(III) reduction [12]. Similarly, ΔmtrF alone showed no deficiency in reducing soluble and insoluble Fe(III), but ΔmtrF/ΔmtrC was incapable of insoluble Fe(III) reduction.

The recent availability of whole genome sequences in dozens of Shewanella species has made it possible to examine the gene cluster of metal reduction in other members of the genus. Interestingly, the genome structure of the mtrBAC-omcA-mtrFED gene cluster is only conserved among closely related species of S. oneidensis[13]. To uncover variations in the molecular mechanism of iron reduction, here we report the characterization of this gene cluster in S. putrefaciens W3-18-1, which differs from S. oneidensis substantially in this gene cluster. In contrast to MR-1, which was isolated from the freshwater sediment of Lake Oneida, NY [14], W3-18-1 was isolated from a Pacific Ocean marine sediment off the coast of Washington State and originally characterized as a psychrophile that is able to reduce metals and form magnetite at 0°C [15]. We showed that MtrC (Sputw2623) was clearly involved in the reduction of Fe2O3, α-FeO(OH), β-FeO(OH) and ferric citrate, while deletion of a novel cytochrome gene (undA or sputw2622) resulted in progressively slower iron reduction in the absence of MtrC and fitness loss under the iron-using condition, indicating a role of UndA in iron reduction. Together, this work delineates a novel molecular mechanism of iron reduction in W3-18-1 that contrasts to what is known in MR-1.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

A list of the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study is described in Additional file 1: Table S1. Shewanella and Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 30 and 37°C, respectively [16, 17]. When needed, antibiotics were added to growth media at the following final concentrations: Kanamycin (Kan), 50 μg/ml; ampicillin (Amp), 50 μg/ml; and gentamycin (Gm), 15 μg/ml. The suicide vector pDS3.0 has been described elsewhere [18]. Anaerobic medium was prepared by boiling the growth medium for 15 minutes with continuous purging with nitrogen gas. Then glass vials or bottles containing the medium were sealed with screw cap and butyl rubber septum followed by autoclave.

Generation of in-frame deletion mutants

In-frame deletions of mtrC, undA or mtrC-undA genes in W3-18-1 were generated by the method of Link et al. [19]. In brief, PCR primers, as shown in Additional file 1: Table S2, were used to amplify 5′- and 3′- end fragments of mtrC, undA or mtrC-undA genes, respectively. The outside primers (D1 and D4) harbored a SacI restriction site. The inside primers (D2 and D3) contained complementary 20-nt tags at their respective 5′ termini. Two fragments flanking mtrC, undA or mtrC-undA genes were amplified by PCR with corresponding primers D1 and D2, D3 and D4, respectively. Then PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Fusion PCR products were generated using the amplified fragments as templates with primers D1 and D4 as described elsewhere [19], then the fusion fragments were ligated into the SacI site of plasmid pDS3.0 and the resulting mutagenesis plasmids (pDS-2622, pDS-2623, pDS-2622-2623, and pDS-4075) were transformed into the donor strain E. coli WM3064 [20]. The transformants were grown on LB supplemented with 0.3 mM diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and transferred to W3-18-1 by conjugation [21]. Integration of mutagenesis plasmids into the chromosome was selected by gentamycin resistance and confirmed by PCR amplification. Then transconjugants were grown in LB broth free of NaCl and plated on the LB plates supplemented with 10% of sucrose. Gentamycin-sensitive and sucrose-resistant colonies were screened by PCR to detect gene deletion, which was subsequently verified by DNA sequencing of the mutated region, and the deletion strain was designated as JZ2622(ΔundA), JZ2623(ΔmtrC) and JZ26223(ΔmtrC-undA).

MtrC, UndA and MtrC-UndA complementation

For complementation, a 2.5-kb DNA fragment containing mtrC and its native promoter, a 2.9-kb DNA fragment containing undA and its native promoter, a 5.3-kb DNA fragment containing mtrC and undA and their native promoters were generated by PCR with W3-18-1 genomic DNA as the template (primers are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2). These fragments were digested with BamHI and ligated to BamHI-digested pBBR1MCS-2 to form pBBR1MCS-2-sputw2623, pBBR1MCS-2-sputw2622, and pBBR1MCS-2-sputw26223. Subsequently, plasmids were electroporated into WM3064 and introduced into the corresponding mutant by conjugation. Kanamycin-resistant colonies of the conjugants were selected for further examination. The presence of plasmids in the complementing strains was confirmed by plasmid purification and restriction enzyme digestion.

Physiological and iron reduction measurement

Three replicates of strains were tested in all physiological experiments, which allows for two-way t test to determine the significance, and non-parametric dissimilarity test using adonis algorithm [22, 23]. All physiological experiments were carried out under anaerobic condition with sodium lactate (20 mM, pH 7.0) as the electron donor, and ferric citrate (20 mM), α-FeO(OH) (20 mM), β-FeO(OH) (20 mM) or Fe2O3 (20 mM) as an electron acceptor. To set up the experiments, cultures were grown to exponential phase aerobically. Approximately ~105 cells were transferred into anaerobic media above and kept still during anaerobic incubation.

The ferrozine assay was used to monitor Fe(III) reduction as previously described [24, 25]. Iron reduction rates were calculated by dividing the differences of Fe(II) concentrations by the differences of time intervals.

Heme stain

To detect the presence of c-type cytochromes, cells were grown anaerobically to the mid-log phase in LB medium supplemented with 50 mM sodium lactate, 20 mM fumarate and 10 mM ferric citrate and then centrifuged. The total cellular proteins were extracted from 0.2 ml cell culture using PeriPreps™ Periplasting kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI). The supernatant containing the cellular protein fraction was resuspended in SDS loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. Heme stains were performed using 3, 3′, 5, 5′-tetramethyl benzidine dihydrochloride as previously described [26].

Competition assay

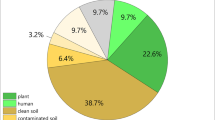

Competition assays were carried out to investigate the involvement of UndA in iron reduction. Wild-type, ΔmtrC, ΔundA and ΔmtrC-undA mutants were grown to exponential phase at OD600 of 0.6 aerobically. Equal volumes of culture were mixed together and inoculated by 1:100 dilutions into anaerobic LB medium supplemented with 50 mM sodium lactate and 20 mM ferric citrate. The co-cultures were transferred to fresh anaerobic medium in 1:100 dilutions on the daily basis. Samples were taken at Day one, three and seven and plated on LB plates aerobically. Colony PCR (96 colonies per plate, 3 replicates) with primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 was used to determine the ratios.

Sequence analysis

Protein sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database by using BLASTP searches. The Clustal W software and the on-line tool Phylodendron (http://iubio.bio.indiana.edu/treeapp/treeprint-form.html) were used for the multiple alignment and phylogenetic tree construction.

Results

Comparison of iron reduction between Shewanella putrefaciensW3-18-1 and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1

W3-18-1 was shown previously to reduce Fe(III) oxide [27], which prompted us to conduct a comparison between W3-18-1 and MR-1 in reducing soluble or insoluble Fe(III) forms. To this end, the abilities of W3-18-1 and MR-1 in Fe(III) reduction were compared in liquid cultures supplemented with one of the following Fe(III) reagents as the sole electron acceptor: ferric citrate, α-FeO(OH), β-FeO(OH), and Fe2O3. All of the iron forms are insoluble except ferric citrate. α-FeO(OH), β-FeO(OH) and Fe2O3 are the major components of goethite, akaganeite and hematite, respectively.

Across all of the five time points examined, W3-18-1 showed consistently higher iron reduction capacities than MR-1 when α-FeO(OH) was provided as electron acceptor (Figure 1). In contrast, iron reduction capacities with other iron forms were similar between W3-18-1 and MR-1. To verify it, a complementary non-parametric multivariate statistical test using adonis algorithm was carried out. The results indicated that the differences between W3-18-1 and MR-1 was significant for α-FeO(OH), but not other irons (see insets of Figure 1).

Comparison of anaerobic (A) α- FeO(OH), (B) β- FeO(OH) (C) Fe 2 O 3 and (D) ferric citrate reduction between MR-1 and W3-18-1. A negative control was included, in which no bacterial cells were inoculated. Reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) was monitored using ferrozine at 562 nm. Data are averages for triplicates and error bars indicate standard deviation. The insets indicate significance of the dissimilarity test of adonis.

Genes implicated in iron reduction

All of the currently sequenced Shewanella genomes except Shewanella denitrificans contain an mtr-omc gene cluster that encodes several proteins predicted to be associated with metal reduction [13, 28]. Among these, mtrBAC are omnipresent and conserved in the cluster (Figure 2A). For example, a Blastp search indicated that W3-18-1 and S. oneidensis MR-1 MtrC share 48% identity and 60% similarity. However, W3-18-1 significantly differs from MR-1 in that the fourth gene of the gene cluster, designated as undA in this study, has no predictable orthologs in most Shewanella species. In addition, S. oneidensis omcA and mtrDEF are absent from the W3-18-1 genome. When protein sequence of undA was compared to that of omcA or mtrF, the results showed that it was 30% identity and 40% similarity, and 25% identity and 37% similarity, respectively. Notably, the identity between undA and omcA are largely attributed to the N-terminus (1–55 amino acids), which might be implicated as a signal peptide.

Sequence analysis of S.putrefaciens W3-18-1 UndA. (A) Schematic representation of the mtr-omc gene cluster in the genomes of selected Shewanella species. (B) The phylogenetic distance of UndA, MtrF, MtrG and MtrA protein sequences within sequenced Shewanella. The arrow points to the location of S. putrefaciens W3-18-1 UndA in the phylogenetic tree.

Conserved genomic synteny is noted for the mtrBAC-undA gene cluster. It is adjacent to a two-gene cluster comprised of feoA and feoB, which encode essential components of the Fe(II) transport system. The DNA interval between two gene clusters is 838 nucleotides.

To investigate the evolutionary aspect of UndA, the phylogenetic analysis of protein sequences was carried out. The results showed that UndA formed a small branch with its orthologs in S. putrefaciens CN32 and S. baltica OS223 (Figure 2B). It was also clustered with UndB, MtrF and MtrG, but separated from OmcA. Notably, the phylogenetic distance of UndA was substantially different from what has been reported from 16S rDNA sequences [29] or the whole genome [27].

Phenotypes of W3-18-1 mutants

To characterize MtrC and UndA of W3-18-1, in-frame deletion mutants of ΔmtrC and ΔundA and a double mutant of ΔmtrC-undA were constructed. Furthermore, the ORF of mtrC or undA was tagged by six histidines, cloned onto an expression vector pBBR1MCS5 and transformed into the corresponding mutant, resulting in ΔmtrC- and ΔundA-complementing strains. The expression of MtrC and UndA in the complementing strains was verified by western blots using anti-his antibodies (data not shown).

A heme staining assay with mutant and complementing strains demonstrated that mtrC and undA encoded heme-containing proteins (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Genome annotation suggests that mtrC and undA encode a decaheme c-type cytochrome with a predicted molecular mass of 69 kDa and an eleven-heme c-type cytochrome with a predicted molecular mass of 88 kDa, respectively. Accordingly, there was no heme-positive band at a position corresponding to 88 kDa and 69 kDa in ΔundA and ΔmtrC mutant, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S1A). Both bands were absent in the ΔmtrC-undA double mutant. Those missing bands in single mutants was restored in the complementing strains (Additional file 1: Figure S1B and S1C).

The ability of ∆mtrC or ∆undA mutant to reduce Fe(III) was compared to that of the wild-type strain. When α-FeO(OH) was supplied, ∆mtrC mutant showed mild iron reduction deficiency (Figure 3A). In addition, significant (P = 0.001) deficiency was detected with β-FeO(OH) (Figure 3B) or Fe2O3 (Figure 3C) as the electron acceptor. When soluble ferric citrate was provided, no iron reduction deficiency was detected (Figure 3D). In contrast, similar iron reduction rates were detected for ∆undA mutant as compared to the wild-type strain (Figure 3), indicating that UndA was not required for iron reduction of W3-18-1.

Comparison of anaerobic (A) α- FeO(OH), (B) β- FeO(OH) (C) Fe 2 O 3 and (D) ferric citrate reduction between W3-18-1 wild-type and Δ mtrC , Δ undA and Δ mtrC-undA mutants. A negative control was included, in which no bacterial cells were inoculated. Reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) was monitored using ferrozine at 562 nm. Data are averages for triplicates and error bars indicate standard deviation. The insets indicate significance of the dissimilarity test of adonis.

Both ∆mtrC and ∆undA mutants were also examined for their ability of Mn(IV) reduction. Mn(IV), present as the insoluble form, could be reduced into soluble Mn(II) by W3-18-1. As shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2A, both wild-type and ∆undA mutant were similar in reducing insoluble Mn(IV) after 22 hour’s incubation, whereas the culture of ∆mtrC mutant remained turbid, which was indicative of Mn(IV) reduction deficiency. Furthermore, ∆mtrC mutant was also deficient in Co(III) (Additional file 1: Figure S2B). Therefore, ∆mtrC mutant was deficient in the reduction of multiple heavy metals. Together, these results suggested that mtrC deletion caused distinct deficiency of metal reduction in W3-18-1, whereas undA deletion had no detectable effects.

Also, we assessed the growth of ∆mtrC mutant under anaerobic conditions with 10 mM lactate as the electron donor, and one of the following four non-metal electron acceptors: 10 mM fumarate, 10 mM TMAO or 10 mM DMSO. The growth patterns were largely similar between wild-type and ∆mtrC mutant (Additional file 1: Figure S2C). Thus, in contrast to a role in metal reduction, MtrC appeared not to utilize organic compounds.

The functional role of UndA in iron reduction

The ability of ∆mtrC-undA double mutant to reduce Fe(III) was examined. Iron reduction rates of ∆mtrC-undA double mutant appeared to be significantly lower than those of wild-type, ∆mtrC and ∆undA single mutants (Figure 3). The ∆mtrC-undA double mutant barely reduced any Fe(III) until 40 hours’ incubation when Fe2O3 was provided, whereas deficiencies were also notable when other Fe(III) forms were provided. Furthermore, iron reduction rates of ∆mtrC-undA double mutant were significantly lower than what was expected from the additive effects of MtrC and UndA single mutants (Additional file 1: Figure S3), indicating that UndA deletion resulted in slower iron reduction in the absence of MtrC.

To further demonstrate the functional role of UndA in iron reduction, competition assays were carried out to examine the fitness gain/loss caused by undA deletion. When wild-type and ∆undA cells were co-cultured in a medium with ferric citrate as the electron acceptor (Figure 4A), wild-type outcompeted ∆undA and gradually became dominant in the population by daily transfers. Similarly, ΔmtrC outcompeted ΔmtrC-undA (Figure 4B). These results indicated that UndA was needed to provide fitness advantage under iron-reducing conditions.

Discussion

Shewanella are commonly present in redox stratified environments [13]. The successful establishment in such niches requires that bacteria adapt to utilize the electron donor or acceptor types in the environment. Accordingly, Shewanella strains are remarkable in utilizing a wide range of electron acceptors. Recent studies showed that S. putrefaciens W3-18-1 exhibited strong reduction of hydrous ferric oxide [30] as well as growth with DNA as sole carbon and energy source [31]. In addition, it could reduce metals and form magnetite at 0°C [15]. Here we further demonstrated that S. putrefaciens W3-18-1 was potent in reducing α-FeO(OH), ferric citrate, β-FeO(OH) and Fe2O3, which might be linked to the iron reduction gene cluster of W3-18-1. Notably, this gene cluster differs substantially from that of MR-1 in that it is comprised of only four genes (mtrBAC and undA) (Figure 2A). The mutational analysis in our study indicated that MtrC was specifically important for metal reduction (Figure 3 & Additional file 1: Figure S2), which was consistent with previous reports that its orthologs in other Shewanella strains played an important role in iron reduction [11, 12]. In contrast, UndA was involved in, but not required for iron reduction. Based on these data, it appears that MtrC and UndA are primary and auxiliary components of iron reduction pathways, respectively.

Recent success in resolving the crystal structure of Shewanella sp. strain HRCR-6 UndA has revealed binding sites for soluble iron chelators [32]. Consistently, our iron reduction and competition experiments suggested that UndA was indeed involved in iron reduction. As a predicted outer membrane lipoprotein, S. putrefaciens UndA might directly interact with extracellular metals. A recent study showed that the UndA ortholog in Shewanella sp. strain HRCR-6 was secreted extracellularly by type II secretion system and participated in ferrihydrite and U(VI) reduction [33]. Interestingly, overexpressing UndA of HRCR-6 partially restored the iron reduction deficiency of ΔmtrC-omcA mutant. It is likely that overexpressing S. putrefaciens UndA could partially replace MtrC as well, since the promiscuity of outer membrane cytochromes can confer Shewanella an advantage to survive and thrive in the natural habitats [34]. Alternatively, S. putrefaciens UndA could function as an interchangeable module of MtrC in its interaction with other components in respiratory electron transfer reactions [12].

S. putrefaciens undA has no obvious orthologs in most Shewanella strains including S. oneidensis MR-1. Because comparative genomic analysis has revealed that UndA substitutes for OmcA in a number of Shewanella species [13, 33], it is possible that UndA has a similar function as OmcA. However, our findings argued against this possibility, as mutant phenotypes of S. oneidensis OmcA differed substantially from those of W3-18-1 UndA in that S. oneidensis OmcA was important for Fe2O3 reduction and no linkage between OmcA and MtrC was detected under ferric citrate-reducing condition [12]. Rather, we noted that S. oneidensis ΔmtrF mutant displayed similar phenotypes as what were observed in our S. putrefaciens ΔundA mutant. It caused no deficiency of iron reduction, but progressively slower iron reduction in the absence of S. oneidensis MtrC [12]. These results suggested that S. oneidensis MtrF might function similarly as S. putrefaciens UndA. In support of this view, the overall structural fold of UndA is significantly similar to that of MtrF, despite low protein sequence identity [32, 35].

Conclusions

Comparative genomic studies have provided important clues into the gene diversity in the respiratory systems. Combining it with experimental studies brings us closer to understand the genetic variations of Shewanella genus. Using these approaches, we show in this study that UndA has a functional relatedness to MtrF, and MtrC and UndA play primary and auxiliary roles in iron reduction of W-3-18-1, respectively.

References

Shi L, Squier TC, Zachara JM, Fredrickson JK: Respiration of metal (hydr) oxides by Shewanella and Geobacter: a key role for multihaem c‒type cytochromes. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 65 (1): 12-20. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05783.x.

Tiedje JM: Shewanella—the environmentally versatile genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2002, 20 (11): 1093-1094. 10.1038/nbt1102-1093.

Viamajala S, Peyton BM, Sani RK, Apel WA, Petersen JN: Toxic effects of chromium (VI) on anaerobic and aerobic growth of shewanella oneidensis MR‒1. Biotechnol Progr. 2004, 20 (1): 87-95.

Lovley DR, Holmes DE, Nevin KP: Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Adv Microb Physiol. 2004, 49: 219-286.

Ziemke F, Brettar I, Höfle M: Stability and diversity of the genetic structure of a Shewanella putrefaciens population in the water column of the central Baltic. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997, 13: 63-74.

Gao H, Obraztova A, Stewart N, Popa R, Fredrickson JK, Tiedje JM, Nealson KH, Zhou J: Shewanella loihica sp. nov., isolated from iron-rich microbial mats in the Pacific Ocean. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006, 56 (8): 1911-1916. 10.1099/ijs.0.64354-0.

Shi L, Chen B, Wang Z, Elias DA, Mayer MU, Gorby YA, Ni S, Lower BH, Kennedy DW, Wunschel DS, et al: Isolation of a high-affinity functional protein complex between OmcA and MtrC: two outer membrane decaheme c-type cytochromes of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J Bacteriol. 2006, 188 (13): 4705-4714. 10.1128/JB.01966-05.

Lower BH, Yongsunthon R, Shi L, Wildling L, Gruber HJ, Wigginton NS, Reardon CL, Pinchuk GE, Droubay TC, Boily JF, et al: Antibody recognition force microscopy shows that outer membrane cytochromes OmcA and MtrC are expressed on the exterior surface of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009, 75 (9): 2931-2935. 10.1128/AEM.02108-08.

Myers JM, Myers CR: Isolation and sequence of omcA, a gene encoding a decaheme outer membrane cytochrome c of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1, and detection of omcA homologs in other strains of S. putrefaciens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998, 1373 (1): 237-251. 10.1016/S0005-2736(98)00111-4.

Myers JM, Myers CR: Role for outer membrane cytochromes OmcA and OmcB of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 in reduction of manganese dioxide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67 (1): 260-269. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.260-269.2001.

Beliaev AS, Saffarini DA, McLaughlin JL, Hunnicutt D: MtrC, an outer membrane decahaem c cytochrome required for metal reduction in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Mol Microbiol. 2001, 39 (3): 722-730. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02257.x.

Coursolle D, Gralnick JA: Modularity of the Mtr respiratory pathway of Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Mol Microbiol. 2010, 77 (4): 995-1008.

Fredrickson JK, Romine MF, Beliaev AS, Auchtung JM, Driscoll ME, Gardner TS, Nealson KH, Osterman AL, Pinchuk G, Reed JL, et al: Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008, 6 (8): 592-603. 10.1038/nrmicro1947.

Myers C, Nealson KH: Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science. 1988, 240: 1319-1321. 10.1126/science.240.4857.1319.

Stapleton RD, Sabree ZL, Palumbo AV, Moyer CL, Devol AH, Roh Y, Zhou JZ: Metal reduction at cold temperatures by Shewanella isolates from various marine environments. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2005, 38 (1): 81-91.

Yang Y, Harris DP, Luo F, Xiong W, Joachimiak M, Wu L, Dehal P, Jacobsen J, Yang Z, Palumbo AV, et al: Snapshot of iron response in Shewanella oneidensis by gene network reconstruction. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 131-10.1186/1471-2164-10-131.

Yang Y, McCue LA, Parsons AB, Feng S, Zhou J: The tricarboxylic acid cycle in Shewanella oneidensis is independent of Fur and RyhB control. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10: 264-10.1186/1471-2180-10-264.

Yang Y, Harris DP, Luo F, Wu L, Parsons AB, Palumbo AV, Zhou J: Characterization of the Shewanella oneidensis fur gene: roles in iron and acid tolerance response. BMC Genomics. 2008, 9 (Suppl 1): S11-10.1186/1471-2164-9-S1-S11.

Link AJ, Phillips D, Church GM: Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997, 179 (20): 6228-6237.

Saltikov CW, Newman DK: Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100 (19): 10983-10988. 10.1073/pnas.1834303100.

Wan XF, Verberkmoes NC, McCue LA, Stanek D, Connelly H, Hauser LJ, Wu L, Liu X, Yan T, Leaphart A, et al: Transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of the Fur modulon in the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186 (24): 8385-8400. 10.1128/JB.186.24.8385-8400.2004.

Anderson MJ: A new method for non‒parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26 (1): 32-46.

Yang Y, Wu L, Lin Q, Yuan M, Xu D, Yu H, Hu Y, Duan J, Li X, He Z: Responses of the functional structure of soil microbial community to livestock grazing in the Tibetan alpine grassland. Glob Change Biol. 2013, 19 (2): 637-648. 10.1111/gcb.12065.

Carter P: Spectrophotometric determination of serum iron at the submicrogram level with a new reagent (ferrozine). Anal Biochem. 1971, 40: 450-458. 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90405-2.

Sorensen J: Reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic, marine sediment and interaction with reduction of nitrate and sulfate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982, 43 (2): 319-324.

Thomas PE, Ryan D, Levin W: Improved staining procedure for detection of Peroxidase-Activity of Cytochrome-P-450 on Sodium Dodecyl-Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gels. Anal Biochem. 1976, 75 (1): 168-176. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90067-1.

Konstantinidis KT, Serres MH, Romine MF, Rodrigues JLM, Auchtung J, Mccue LA, Lipton MS, Obraztsova A, Giometti CS, Nealson KH, et al: Comparative systems biology across an evolutionary gradient within the Shewanella genus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106 (37): 15909-15914. 10.1073/pnas.0902000106.

Gao H, Wang X, Yang ZK, Palzkill T, Zhou J: Probing regulon of ArcA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 by integrated genomic analyses. BMC Genomics. 2008, 9: 42-10.1186/1471-2164-9-42.

Zhao JS, Deng Y, Manno D, Hawari J: Shewanella spp. genomic evolution for a cold marine lifestyle and in-situ explosive biodegradation. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (2): e9109-10.1371/journal.pone.0009109.

Salas EC, Berelson WM, Hammond DE, Kampf AR, Nealson KH: The impact of bacterial strain on the products of dissimilatory iron reduction. Geochim Cosmochim Ac. 2010, 74 (2): 574-583. 10.1016/j.gca.2009.10.039.

Pinchuk GE, Ammons C, Culley DE, Li SMW, McLean JS, Romine MF, Nealson KH, Fredrickson JK, Beliaev AS: Utilization of DNA as a sole source of phosphorus, carbon, and energy by Shewanella spp.: ecological and physiological implications for dissimilatory metal reduction. Appl Environ Microb. 2008, 74 (4): 1198-1208. 10.1128/AEM.02026-07.

Edwards MJ, Hall A, Shi L, Fredrickson JK, Zachara JM, Butt JN, Richardson DJ, Clarke TA: The crystal structure of the extracellular 11-heme Cytochrome UndA reveals a conserved 10-heme motif and defined binding site for Soluble Iron Chelates. Structure. 2012, 20 (7): 1275-1284. 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.016.

Shi L, Belchik SM, Wang Z, Kennedy DW, Dohnalkova AC, Marshall MJ, Zachara JM, Fredrickson JK: Identification and characterization of UndAHRCR-6, an outer membrane endecaheme c-type cytochrome of Shewanella sp. strain HRCR-6. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011, 77 (15): 5521-5523. 10.1128/AEM.00614-11.

Bouhenni RA, Vora GJ, Biffinger JC, Shirodkar S, Brockman K, Ray R, Wu P, Johnson BJ, Biddle EM, Marshall MJ, et al: The role of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 outer surface structures in extracellular electron transfer. Electroanal. 2010, 22 (7–8): 856-864.

Clarke TA, Edwards MJ, Gates AJ, Hall A, White GF, Bradley J, Reardon CL, Shi L, Beliaev AS, Marshall MJ, et al: Structure of a bacterial cell surface decaheme electron conduit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011, 108 (23): 9384-9389. 10.1073/pnas.1017200108.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by grants to Yunfeng Yang from National Science Foundation of China (41171201) and National Key Basic Research Program of China (2013CB956601), to Jizhong Zhou by The United States Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research under the Genomics: GTL Program through the Shewanella Federation, and the Microbial Genome Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JC and DQ generated the constructs and strains used. YY, JC and DQ generated and analyzed the results. YY and JZ designed the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yunfeng Yang, Jingrong Chen contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Chen, J., Qiu, D. et al. Roles of UndA and MtrC of Shewanella putrefaciensW3-18-1 in iron reduction. BMC Microbiol 13, 267 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-267

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-267