Abstract

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii is a notorious opportunistic pathogen mainly associated with hospital-acquired infections. Studies on the clonal relatedness of isolates could lay the foundation for effective infection control. A snapshot study was performed to investigate the clonal relatedness of A. baumannii clinical isolates in our local settings.

Results

Among 82 non-repetitive Acinetobacter spp. clinical isolates that were recovered during a period of four days in 13 hospitals in Sichuan, Southwest China, 67 isolates were identified as A. baumannii. Half of the 67 A. baumannii isolates were non-susceptible to carbapenems. blaOXA-23 was the only acquired carbapenemase gene detected, present in 40 isolates including five carbapenem-susceptible ones. The isolates belonged to 62 pulsotypes determined by PFGE and 31 sequence types (ST) by multi-locus sequence typing. Forty-three isolates belonged to the globally-disseminated clonal complex 92, among which ST75, ST92 and ST208 were the most common sequence types.

Conclusions

Clinical isolates of A. baumannii were diverse in clonality in this snapshot study. However, most of the isolates belonged to the globally-distributed clonal complex CC92. ST75, ST92 and ST208 were the most common types in our region. In particular, ST208 might be an emerging lineage carrying blaOXA-23.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the common bacterial species responsible for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) [1]. The prevalence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) A. baumannii in hospitals has been increasing worldwide [2], representing a serious challenge for clinical management and public health. Investigation on the clonal relatedness of A. baumannii in local settings could generate useful data to understand the local epidemiology of this opportunistic pathogen and therefore lay a foundation for an effective infection control program. Previous studies have focused on the clonal relatedness of A. baumannii but the vast majority of these studies were retrospective and used a collection of isolates either from outbreaks or with little information on their representativeness. For hospitals in Sichuan, Southwest China, A. baumannii was a huge problem as it was the most common bacterial species associated with HAIs and accounted for 17.3% of putative pathogens causing HAIs in a point prevalence survey [3]. Outbreaks due to A. baumannii had also been reported in our hospitals [4]. A snapshot study was therefore performed to investigate the clonal relatedness of A. baumannii clinical isolates in our local settings.

Results and discussion

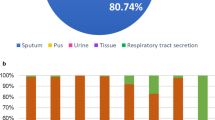

Among 82 non-repetitive isolates that were recovered from clinical specimens from June 22 to June 25, 2011 in 13 hospitals in Sichuan and were putatively identified as A. baumannii by automated microbiology systems, 67 isolates were validated to be A. baumannii. The vast majority (61/67, 91%) of the A. baumannii isolates were recovered from sputa or respiratory tract secretions. The remaining six isolates were from ascites, cerebrospinal fluid, drainage, pleural fluid or wound secretions. As for the clinical significance, A. baumannii isolates were considered as either colonizers (55.2%) or pathogens (44.8%) causing clinical infections.

About half of the A. baumannii isolates (35/67, 52.2%) were non-susceptible to carbapenems (34 non-susceptible to both imipenem and meropenem and 1 non-susceptible to meropenem only), which was in consistence with the 53% carbapenem resistance rate of A. baumannii in the 2010 report of Chinese Ministry of Health National Antimicrobial Resistance Investigation Net (MOHNARIN) [5]. Many isolates were non-susceptible to sulbactam (35/67, 52.2%), ceftazidime (39/67, 58.2%), ciprofloxacin (43/67, 64.2%) or cotrimoxazole (47/67, 70.1%) while all isolates were susceptible to polymyxin and rifampicin and only one isolate was non-susceptible to minocycline.

blaOXA-23 was the only acquired carbapenemase gene that was detected. Interestingly, it was present in 35/35 carbapenem-non-susceptible and 5/32 carbapenem-susceptible isolates. blaOXA-23 has been the most common carbapenemase gene in China, as a previous study reported that 322 out of 342 (94.2%) imipenem-non-susceptible A. baumannii isolates collected from 16 Chinese cities had blaOXA-23[6]. Although blaOXA-23 encodes a carbapenemase, this gene has also been detected in carbapenem-susceptible isolates before [7].

The isolates were assigned to 62 pulsotypes determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), suggesting quite diverse clonal relatedness (Figure 1). A total of 31 sequence types (STs), including 19 new STs, were assigned for the isolates using the multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) with the pubmlst scheme (Table 1 and Figure 2). As the gdhB gene sequence was not obtained from isolate d34 despite repeated attempts using various primer pairs, the ST could not be assigned for this isolate. Of note, two isolates of the same pulsotypes were assigned to different STs, ST118 and ST218. However, ST118 and ST218 were found to be single locus variants to each other. This was in consistence with a previous study [8] reporting that isolates belonging to the same puslotype were not always of the same STs.

PFGE patterns of A. baumannii isolates. Dendrogram was generated by BioNumerics software with the unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages (UPGMA). Isolate name, ST, CC and the carriage of blaOXA-23 (Y, positive; N, negative) are indicated. The ST numbers shown after slash are assigned using the Pasteur MLST scheme.

STs seen in this study and the CC92. Panel A. The relatedness of the STs seen in this study. Panel B. The clonal complex 92 (CC92). eBURST was performed using 6 as the minimum identical loci for the definition of CC and 3 as the minimum single locus variants. The countries of isolation are shown according to the pubmlst database. The STs found in this study are in bold. NA, information not available. ST208 is predicted as the founder ST for CC92 by eBURST.

ST75, ST92 and ST208 were the most common STs in our local settings as each of them were found in three to five hospitals scattered in different regions of the province. ST92 and ST75 were prevalent in West China Hospital in a study carried out in 2006 [7] and were also the most common STs in China in 2005 [9]. In contrast, ST208 had not been identified in China before, although it was found in five hospitals in this study. All our ST208 isolates except one carried blaOXA-23. ST208 has recently become one of the two most common STs of carbapenem-non-susceptible isolates in the United States [10], suggesting that ST208 might be an emerging lineage carrying carbapenem resistance determinants.

ST92, a globally-distributed type, and its 103 closely-related STs including ST75, ST118, ST136, ST138, ST191, ST208, ST218, ST368, ST381 and ST433 detected in this study comprised the clonal complex 92 (CC92, Figure 2), corresponding to the pan-European clone II (EUII; the international clone 2) [11]. Although diverse types were detected, 43 isolates belonged to the CC92. Among the 104 STs of CC92, 35 STs were different from ST92 only in the gpi locus. Isolate information was available for 22 of these 35 STs, 14 of which have only been found in the East or Southeast Asia at present. The 20 non-CC92 STs identified in the present study were either singletons (n = 12) or of a CC that was not a common international clone (Table 1).

A total of 575 STs were assigned in the Acinetobacter MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/, accessed by May 19, 2013), among which isolates identified as A. baumannii belonged to 545 STs. The 305-bp gpi locus of A. baumannii appeared to diverge much faster than other loci, with 149 gpi allele types comparing to 45 gltA, 84 gyrB, 85 gdhB, 53 recA, 42 cpn60 and 63 rpoD. The occurrence of a different gpi allele for every three STs deposited in the pubmlst database raised the concern that gpi might not be an ideal locus for typing. A previous study [8] also suggested that gpi was not a good candidate for MLST analysis due to recombination. Therefore, the diversity of A. baumannii generated by variations in the gpi locus alone might need validation to appreciate whether the diversity is truly meaningful.

Isolates belonging to each of 19 new STs were assigned to 18 STs using the Pasteur scheme (Table 1). Among the 18 STs determined by the Pasteur scheme, 12 had not been seen before and therefore were truly new STs. Although 411 STs of A. baumannii had been assigned in the pubmlst database before this study, a few new STs were still detected in a relatively small collection, suggesting that A. baumannii is likely to be extremely diverse in clonal origins or is undergoing a significant clonal expansion. Of note, the isolates with new STs were all carbapenem-susceptible except one. blaOXA-23 was not detected in most (17/21) isolates of the novel STs. This phenomenon was also present in this study as all the local carbapenem-resistant isolates carrying blaOXA-23 belonged to CC92. It has been suggested that among carbapenem-resistant isolates some belonging to certain clonal complexes appeared to be more successful [12–14].

The diversity of A. baumannii isolates in our settings could provide useful information for infection control. The clonal diversity of A. baumannii and the fact that carbapenem resistance could be transmitted horizontally highlight that “horizontal” infection control measures such as environmental cleaning and hand hygiene should be reinforced to reduce the further spread of A. baumannii. Person-to-person transmission of carbapenem-non-susceptible A. baumannii carrying blaOXA-23 was indeed identified for several cases as evidenced by the fact that isolates recovered from different patients belonged to the same pulsotype (Table 1 and Figure 1). This suggests that effective infection control measures might need to include rapid identification of blaOXA-23 by molecular methods and also justifies contact precautions for patients with carbapenem-resistant isolates.

Conclusions

This study provided a snapshot of A. baumannii population in clinical samples in our local settings. Significantly diverse clonal origins were identified but most isolates belonged to the globally-distributed CC92. Among CC92, ST75, ST92 and ST208 were the most common types in our region. The high prevalence of ST208 carrying blaOXA-23 suggests that ST208 appears to be an emerging lineage mediating the spread of carbapenem resistance. The diversity of A. baumannii suggested that the current MLST scheme might need to be further optimized and in particular the gpi gene might not be an ideal target for Acinetobacter MLST.

Methods

Strains

The study included all non-repetitive isolates (n = 82) that were recovered from clinical specimens from June 22 to June 25, 2011 in 13 hospitals in Sichuan, southwest China and were putatively identified as A. baumannii or belonging to the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex using the Vitek II, MicroScan and Phoenix automated systems. The clinical samples were taken as part of standard patient care and therefore no ethical approval was applied for their use. The 13 hospitals are all tertiary with 19,051 beds in total (ranged from 800 to 4,300) including 3 university hospitals and 10 municipal ones. For each patient, only one isolate was collected. Genomic species identification was established by partially sequencing the recA gene as described previously [15].

In vitrosusceptibility test

MICs of meropenem, imipenem, ceftazidime, sulbactam, minocycline, polymyxin, ciprofloxacin, rifampicin and cotrimoxazole against A. baumannii isolates were determined using the agar dilution method following the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [16]. MICs were interpreted according to the breakpoints established by CLSI [16], except for sulbactam and rifampicin, for which breakpoints from the French Society for Microbiology were used (for sulbactam, ≤8 mg/L for susceptible; for rifampicin, ≤8 μg/ml for susceptible and <16 mg/L for resistant) [17]. Resistance to imipenem or meropenem was defined as carbapenem resistance.

Detection of carbapenemase-encoding genes

Genes encoding Class A carbapenemases (blaGES and blaKPC), Class B metallo-β-lactamases (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaSPM, blaGIM, blaSIM and blaNDM) or Class D OXA-type carbapenemases (blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23, blaOXA-24, blaOXA-58 and blaOXA-143) were screened as described previously [18–22]. Purified amplicons were sequenced in both directions using an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Similarity searches were carried out using BLAST programs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Strain typing

PFGE was employed to determine clonal relatedness of the isolates and was performed as described previously [12]. PFGE band patterns were analyzed using the BioNumerics software, version 6.6.4.0 (Applied Maths, St-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Pulsotypes were defined as isolates with PFGE band patterns of 80% similarity or above [23].

All A. baumannii isolates were subjected to MLST targeting seven housekeeping genes, gltA, gyrB, gdhB, recA, cpn60, gpi and rpoD[24]. As primers used previously were unable to amplify the gdhB and gpi alleles for some isolates [9, 24, 25], new primers were therefore designed for gdhB (gdhBxF1: ATTGGTTGCTGCCGAATAGT; gdhBxR1: TATGGGGGCCAGATAATCAA) and gpi (gpi-F2: AAAATCCATGCTGGGCAATA; gpi-R2: CCGAGTAATGCCATGAGAAC) genes [24]. New STs were deposited in the Acinetobacter MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii/). eBURST (version 3, http://eburst.mlst.net/) was used to assign STs to CCs, which were defined for those sharing identical alleles at six of seven loci. CCs were named according to the number of the predicted founder ST except for CC92, which has been well defined in literature. If no founder ST was predicted by eBURST, the CC was named by the first ST assigned.

Isolates with new STs and isolate d34, of which ST could not be determined using the pubmlst scheme, were also subjected to MLST using the Pasteur scheme [26]. New STs determined using the Pasteur scheme have also been deposited into the database (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst/Abaumannii.html).

References

Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL: Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008, 21: 538-582.

Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H: An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007, 5: 939-951.

Zong Z, Qiao F, Yin W, Xu S: A large-scale survey on the point prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in southwest China. IDWeek. 2012, San Diego, CA: Poster Nr, 1171-

Zong Z, Lu X, Valenzuela JK, Partridge SR, Iredell J: An outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii producing OXA-23 carbapenemase in western China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008, 31: 50-54.

Li Y, Lu Y, Wang S: Mohnarin report 2010: surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in nonfermenting gram-negative bacteria. Chin J Nosocomiol. 2011, 21: 5133-5137. (behalf of Mohnarin)

Zhou H, Yang Q, Yu YS, Wei ZQ, Li LJ: Clonal spread of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii among different cities of China. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 4054-4057.

Wang X, Zong Z, Lu X: Tn2008 is a major vehicle carrying blaOXA-23 in Acinetobacter baumannii from China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011, 69: 218-222.

Hamouda A, Evans BA, Towner KJ, Amyes SG: Characterization of epidemiologically unrelated Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from four continents by use of multilocus sequence typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and sequence-based typing of blaOXA-51-like genes. J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48: 2476-2483.

Fu Y, Zhou J, Zhou H, Yang Q, Wei Z, Yu Y, Li L: Wide dissemination of OXA-23-producing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal complex 22 in multiple cities of China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65: 644-650.

Adams-Haduch JM, Onuoha EO, Bogdanovich T, Tian GB, Marschall J, Urban CM, Spellberg BJ, Rhee D, Halstead DC, Pasculle AW, et al: Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Acinetobacter baumannii in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49: 3849-3854.

Mugnier PD, Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P: Worldwide dissemination of the blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010, 16: 35-40.

Seifert H, Dolzani L, Bressan R, van der Reijden T, Van Strijen B, Stefanik D, Heersma H, Dijkshoorn L: Standardization and interlaboratory reproducibility assessment of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-generated fingerprints of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 4328-4335.

Karah N, Sundsfjord A, Towner K, Samuelsen O: Insights into the global molecular epidemiology of carbapenem non-susceptible clones of Acinetobacter baumannii. Drug Resist Updat. 2012, 15: 237-247.

Zarrilli R, Pournaras S, Giannouli M, Tsakris A: Global evolution of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal lineages. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013, 41: 11-19.

Krawczyk B, Lewandowski K, Kur J: Comparative studies of the Acinetobacter genus and the species identification method based on the recA sequences. Mol Cell Probes. 2002, 16: 1-11.

CLSI: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-First Informational Supplement. 2011, Wayne, PA: The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

Comite’de lAntibiogramme de la Socie’te’ Franc¸aise de Microbiologie: Communique’. 2009, Paris, France: Socie´te´ Franc¸aise de Microbiologie

Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, Amyes SG, Livermore DM: Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006, 27: 351-353.

Higgins PG, Lehmann M, Seifert H: Inclusion of OXA-143 primers in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 35: 305-

Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N: Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007, 59: 321-322.

Poirel L, Le Thomas I, Naas T, Karim A, Nordmann P: Biochemical sequence analyses of GES-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and the class 1 integron In52 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000, 44: 622-632.

Bradford PA, Bratu S, Urban C, Visalli M, Mariano N, Landman D, Rahal JJ, Brooks S, Cebular S, Quale J: Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species possessing the class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing KPC-2 and inhibitor-resistant TEM-30 β-lactamases in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 39: 55-60.

Van Belkum A, Tassios PT, Dijkshoorn L, Haeggman S, Cookson B, Fry NK, Fussing V, Green J, Feil E, Gerner-Smidt P, et al: Guidelines for the validation and application of typing methods for use in bacterial epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007, 13 (Suppl 3): 1-46.

Bartual SG, Seifert H, Hippler C, Luzon MA, Wisplinghoff H, Rodriguez-Valera F: Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 4382-4390.

Hamidian M, Hall RM: AbaR4 replaces AbaR3 in a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolate belonging to global clone 1 from an Australian hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 2484-2491.

Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Brisse S: The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e10034-

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from China US Collaborative Program on Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases and by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project no. 81101293).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WX carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. QF carried out the species identification. YR participated in the susceptibility tests. GY participated in the PCR. ZZ conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Qiao, F., Yu, R. et al. Clonal diversity of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates revealed by a snapshot study. BMC Microbiol 13, 234 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-234

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-234